Eight

CRAFT DEMONSTRATORS

Mountain folk learned to make a living by sharing their crafts with the public. This chapter contains photographs archived with the Blue Ridge Parkway headquarters in Asheville, North Carolina. They showcase many handcrafts done by people living in the Blue Ridge Mountains and were taken by various photographers documenting the craft skills.

Some of the crafts shown in this chapter are fiber weaving, chair caning, basket weaving, whittling, apple butter making, sorghum molasses preparation, and the construction of musical instruments.

Most everything was made by hand in the mountains, including dwellings. Log cabins were hewn from logs found on the property. Rocks were gathered for foundations. Homemade cement was mixed from the sand found in the flowing rivers. Food was grown by the local farmer for his family, while extra was sold at market or to neighbors. Clothes were made from handspun fibers grown on the farm.

The Blue Ridge crafts heritage was founded in North Carolina and Virginia. Visitors from all over the world travel to the Blue Ridge Mountains in search of fine crafts. Here visitors can see artists at work in their studios, participate in hands-on demonstrations, view a great variety of crafts at galleries and museums, and learn about the crafts heritage. Today many people come to the region’s venerable craft schools—for a weekend, a week, or longer—to learn a craft, refine their skills, or learn about Appalachian arts and crafts.

During the Depression, the federal Works Progress Administration fostered crafts projects as well as public works and murals. This enabled crafts to flourish at a local level. At the same time, American art programs began to include craft studies in their curricula.

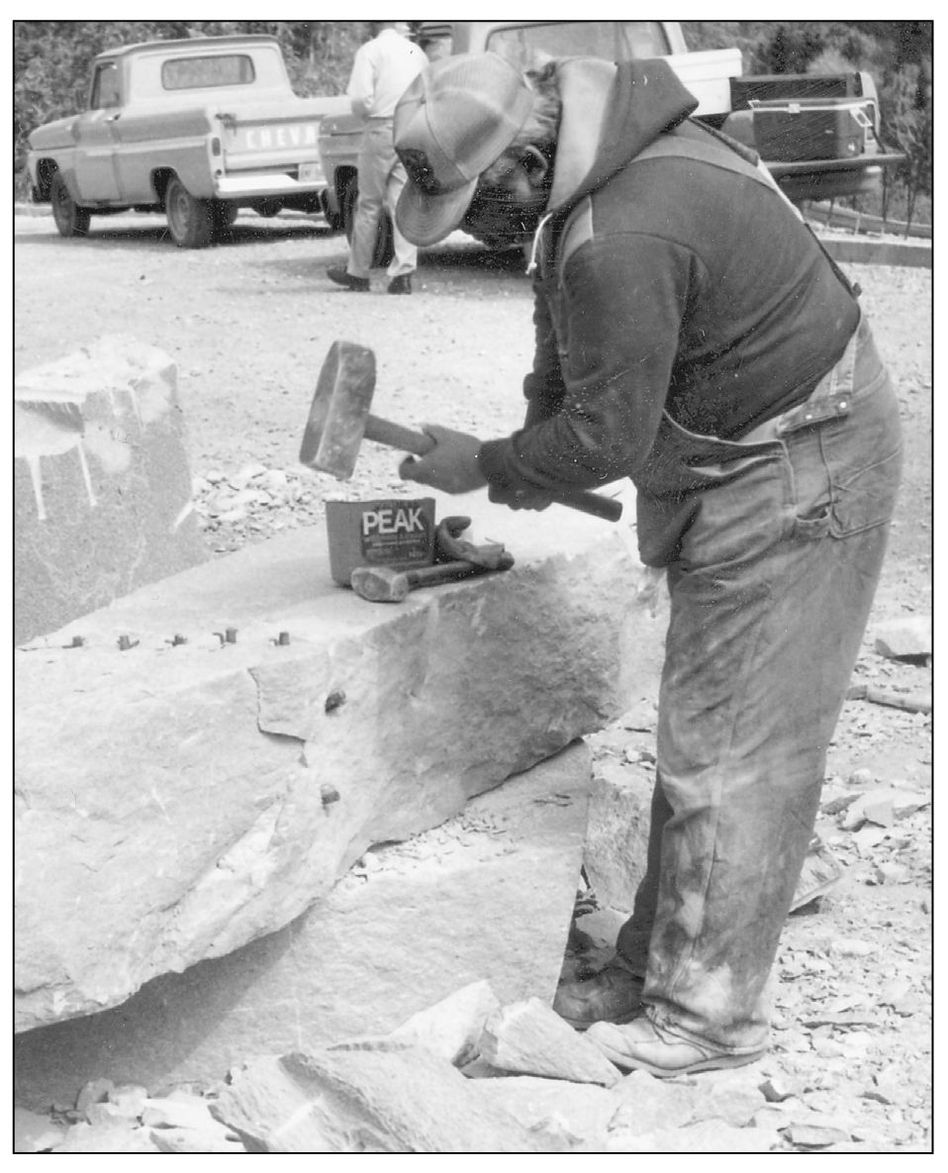

VIADUCT STONEMASON. Throughout the Blue Ridge Parkway project, local stone was used to face bridges and tunnels. This stonemason was creating the facing to be used at the Linn Cove Viaduct next to Grandfather Mountain. Known for their talent, stonemasons from Italy were hired in the early construction stages of the parkway. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

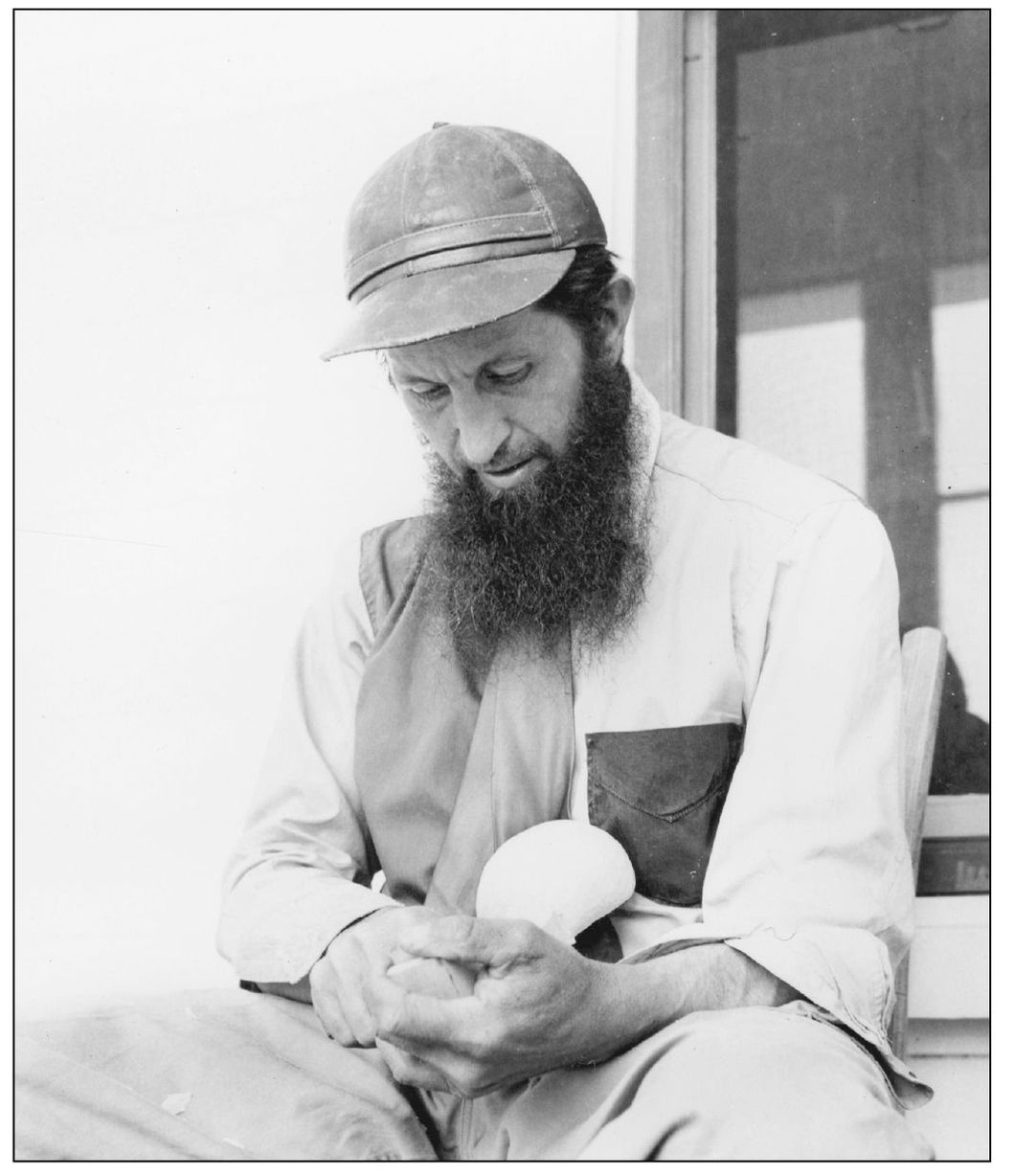

GUN STOCK MANUFACTURING. On September 2, 1959, Reed Clifton demonstrated the art of gun stock manufacturing in Vesta, Virginia. Rifles and shotguns bore the manufacturer’s signature in the early days of America. High-quality wood was used to carve elaborate scenes or details. Custom-fitted stocks ensured accurate shooting by the serious shooter. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

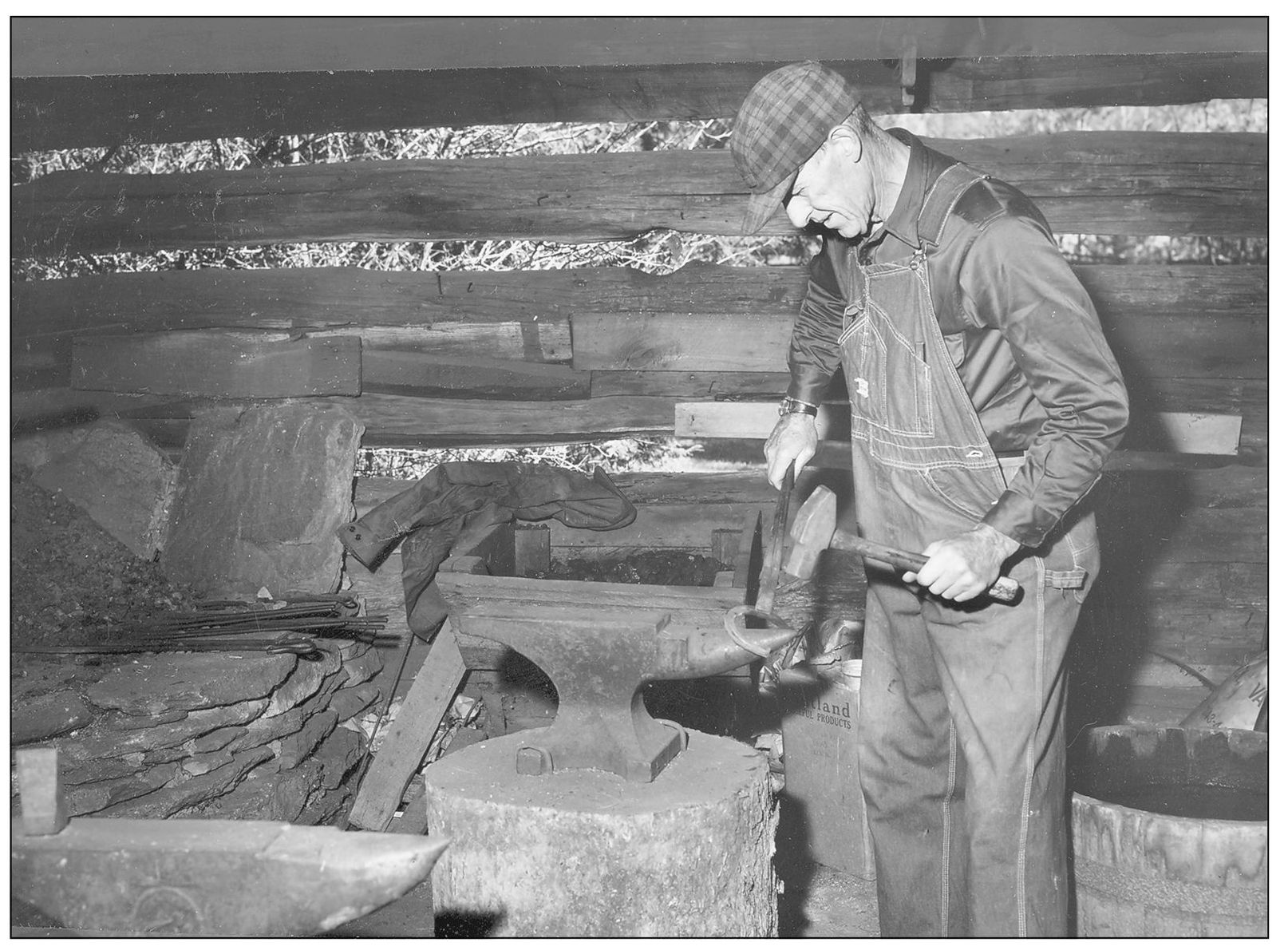

MABRY MILL BLACKSMITH. This blacksmith is creating objects from iron or steel by “forging” the metal, which means using hand tools to hammer, bend, cut, and shape metal in its non-liquid form. Usually the metal is heated until it glows red or orange as part of the forging process. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

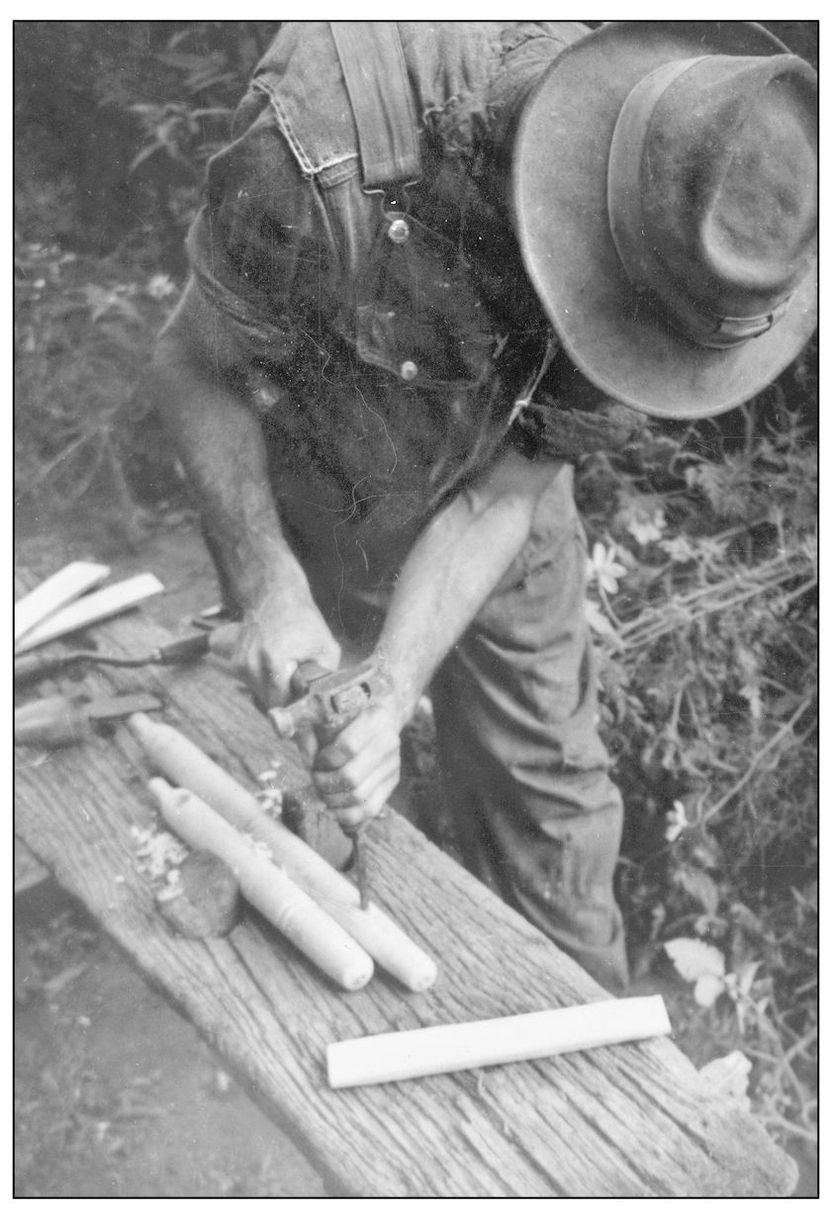

WHITTLING. The art of carving shapes out of raw wood with a knife is called “whittling.” Whittling was a big hobby for country folks in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Typically a pocketknife is the instrument of choice, and oftentimes figurines are the end result. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

HANDMADE CHAIR. Handmade chairs were very common in the early 1900s. Very few tools were needed to craft a simple chair. Often one-of-a-kind chairs were a work of art made to fit the person receiving the chair. This chair was made in 1953 at a demonstration near Fancy Gap, Virginia. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

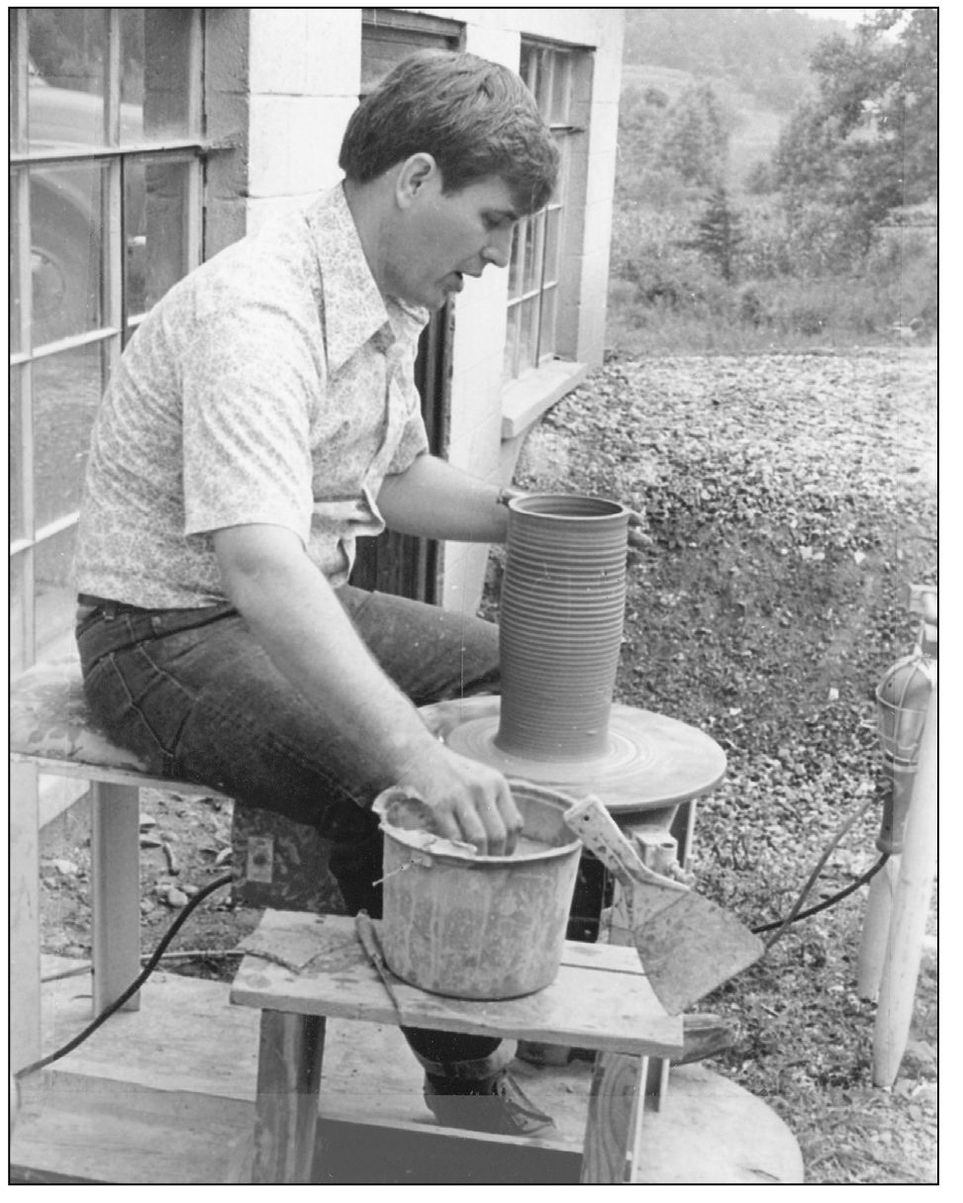

JIM SOCKWELL POTTERY MAKING. History and memories are spun by Appalachian potters. Early pieces of pottery included milk jugs, crocks, pitchers, and decorative vases. Cherokee pottery served not only in day-to-day uses but also ceremonial uses. Today it is considered fine art. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

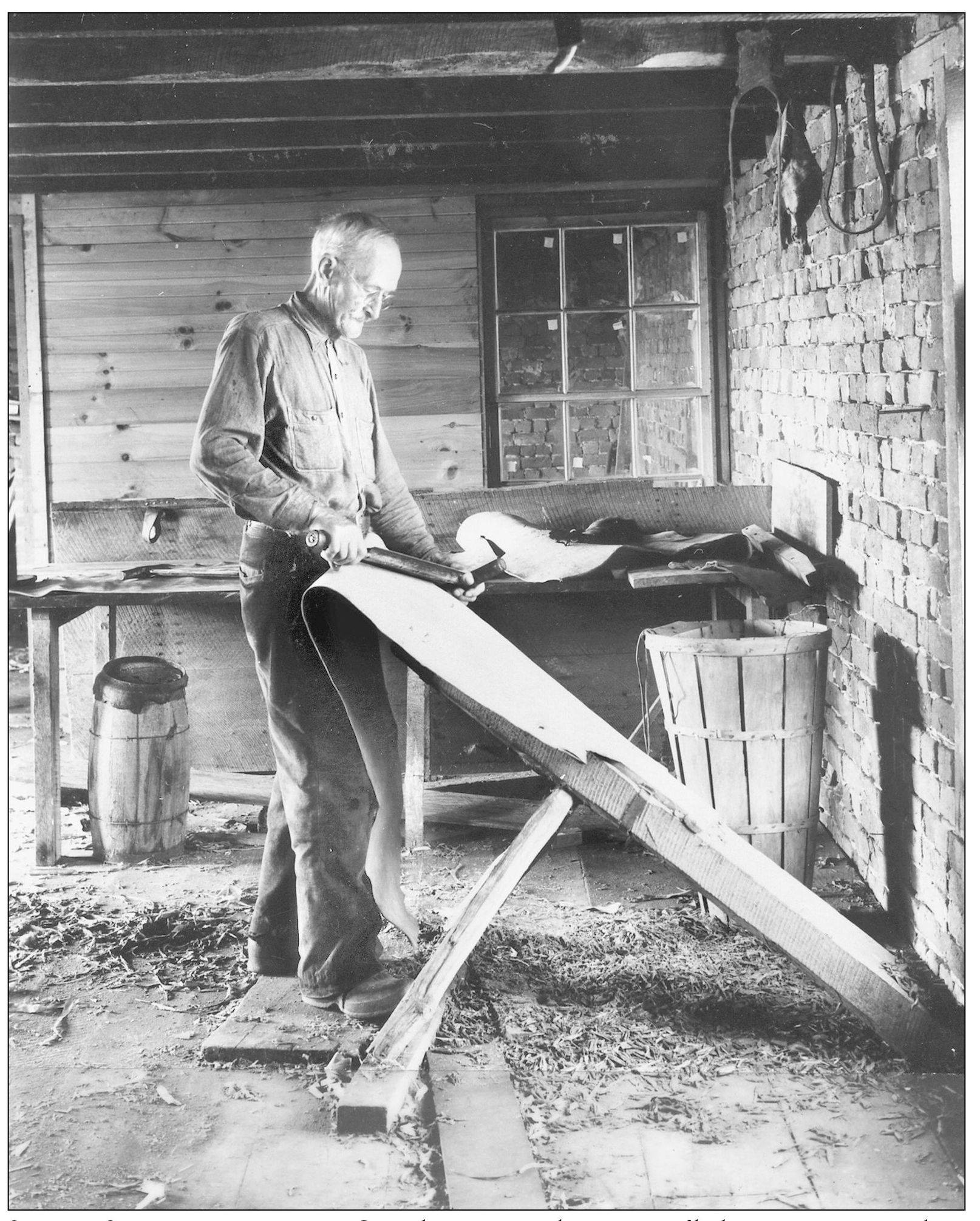

SIMON P. SCOTT TANNING HIDES. Scott demonstrates the tanning of hides in 1941 near Meadows of Dan, Virginia. Here he is scraping the hide after removal from the tanning vat and preparing the hide for oiling. Oiling waterproofed the hides to be used as hats, coats, and tents. The term “tanning” refers to the concept of infusing the animal hide with the preservative “tannic acid.” This prevents the skin from rotting. The most common method, historically, was “brain tanning.” There is tannic acid, as well as oils and conditioners, in the brain that will transform a raw piece of animal hide into supple, garment-grade leather. The hide is removed from the carcass and then laced to a rigid frame. The hair and dermis is scraped from the outer layer of skin, and the fatty sub-tissue is scraped from the underside. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

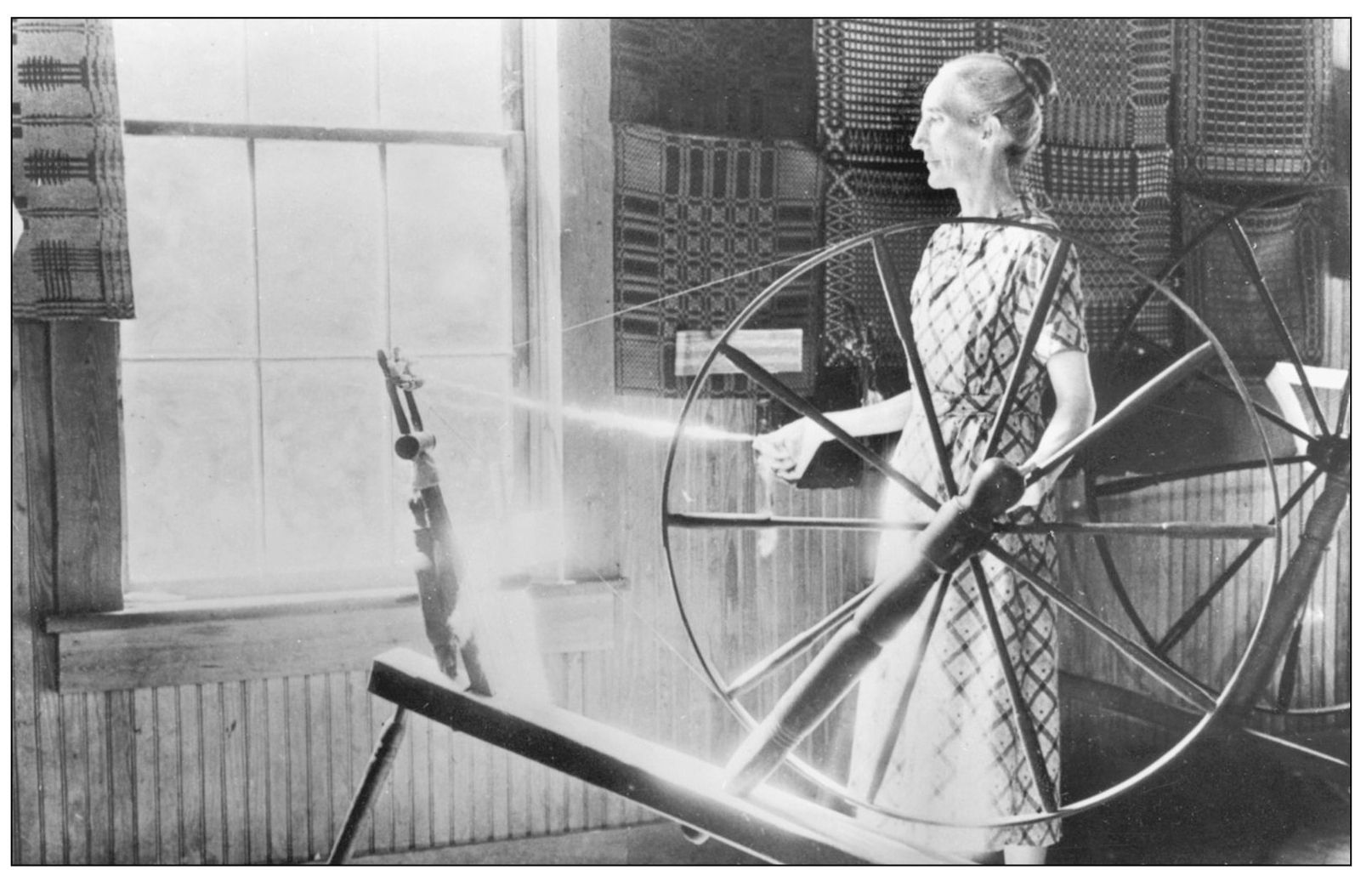

SPINNING AT BRINEGAR CABIN. This century-old spinning wheel is still used in craft demonstrations in the summer months at Brinegar Cabin at milepost 238.5. Other demonstrations may include quilting, old-time mountain music, weaving, and other crafts unique to the beginning of the 20th century. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

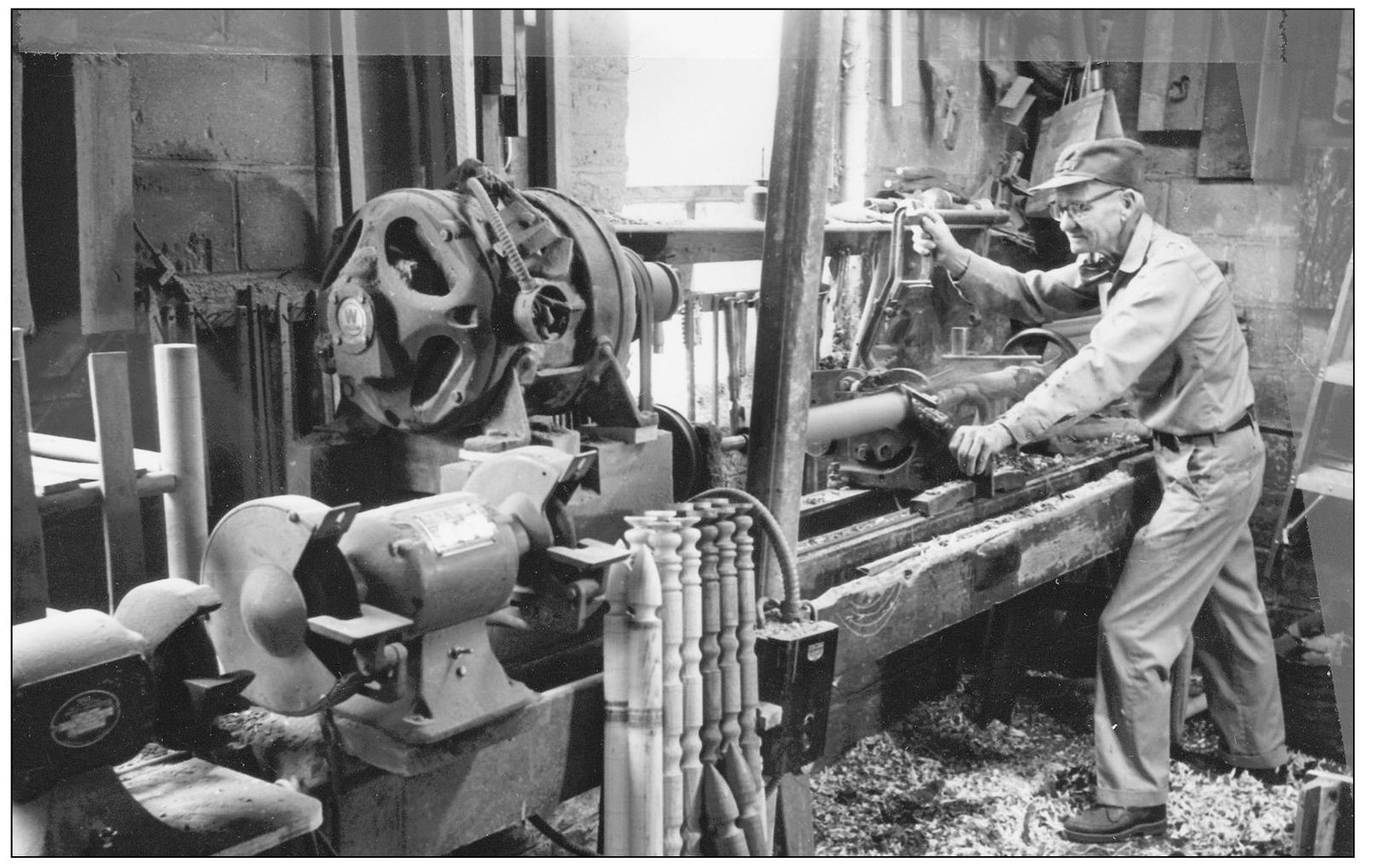

TURNING A CHAIR LEG. Arvel Woody and his brother Walter entered the chair-making business after World War II. While the current designs have been modernized, the mortises are still cut with a machine manufactured in 1893, and the chairs continue to be assembled without glue. (Courtesy of a private collection.)

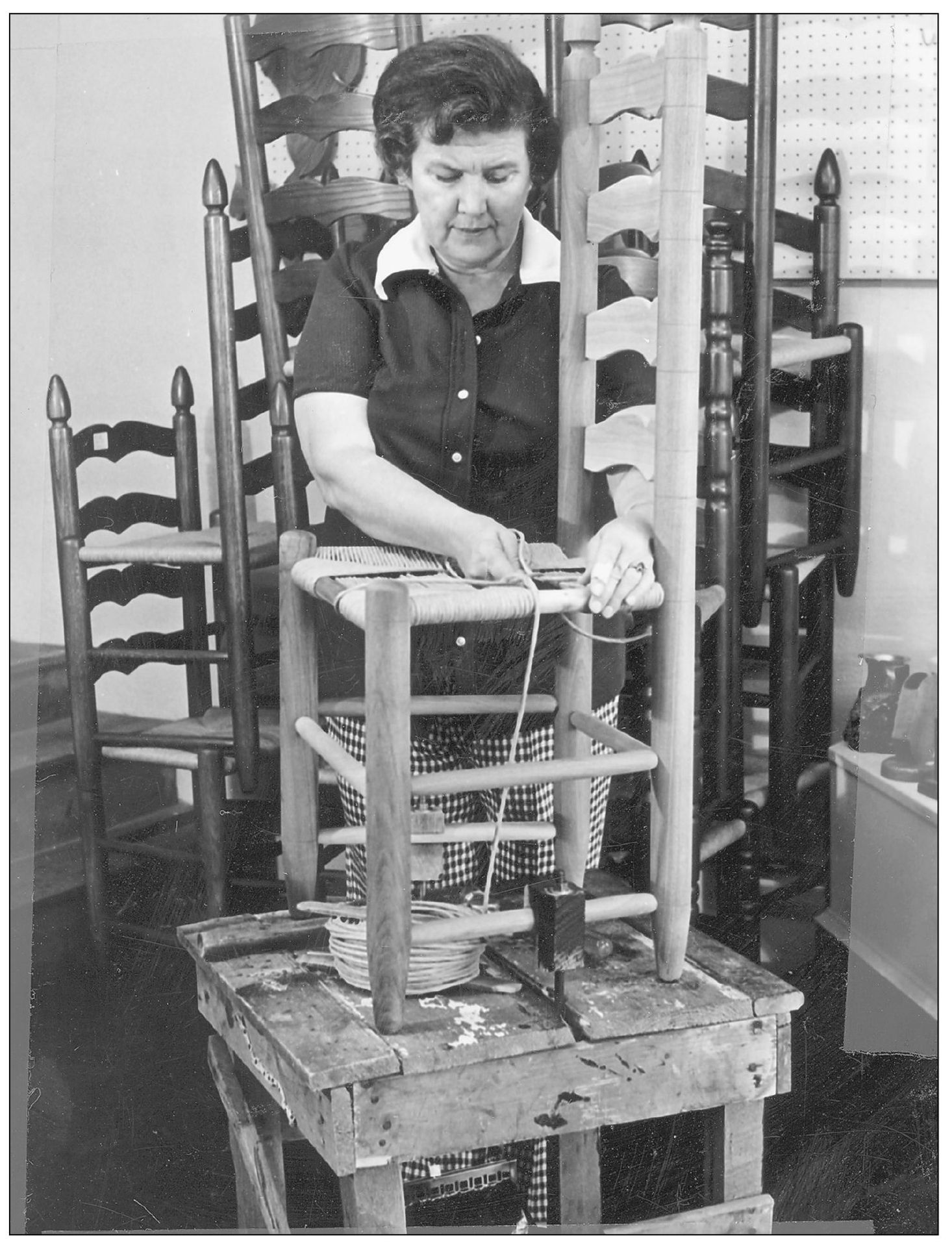

SEAT WEAVING AT WOODY’S CHAIR SHOP. Splints, sometimes referred to as “splits,” are prepared strips of ash, oak, reed, or hickory bark woven around the seat rungs or dowels of chairs and rockers, usually in a herringbone-twill or basket-weave design. The rustic or lattice weave uses rawhide strips that are woven on chairs, rockers, and couches in a very open weave. Arvel Woody’s grandfather, Arthur, made traditional “mule-eared” chairs. They were taken by ox-drawn sled to Marion and Forest City, North Carolina, to be exchanged for coffee and sugar at a rate of three chairs per $1. Arthur’s career as a chairmaker coincided with the handicraft revival, and his work became popular in the North. He had an endless variety of chairs. Shipping chairs across the country to cities like Boston was common for him. When he and his son began teaching chair bottoming at Penland School in the 1920s, his reputation grew. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)