“What do you mean, I can’t take this on the bus?” I asked Cheryl, the school bus driver. “I have to take this to school. It’s really important.”

“No, it’s too big. It’s against regulations. There’s no place to put it. You’re not allowed to block the aisle and it’s too big to put under the seat.”

“I can put it on the seat beside me, and the sewing machine under the seat,” I said, lifting the bin with the twenty-eight purses onto the bus.

“We’d have to leave someone behind. There wouldn’t be enough room, Lacey.”

I looked at my sister yawning at the bottom of the bus steps. She had Kayden in her arms and the sewing machine in its case by her feet. “Angel will stay behind and catch the later bus,” I offered. “That leaves one seat empty, plus Kayden’s car seat space. So then there’s enough room.”

Cheryl looked down at Angel. “That OK with you?”

“Sure,” Angel said, yawning again. “I had a late night. Too bad I didn’t know before I got out of bed.”

I beamed at Angel. “Thank you! I’ll make it up to you,” I promised, as I took the sewing machine from her.

Unusual things were already happening by the time Cheryl dropped me off at Sequoia. A television crew was there, and a reporter introduced himself. The reporters all wanted to talk to me, but there was still work to be done. While TV people were setting up cameras, the boys from Sequoia were rearranging the church pews. They even set up a table for the sewing machine.

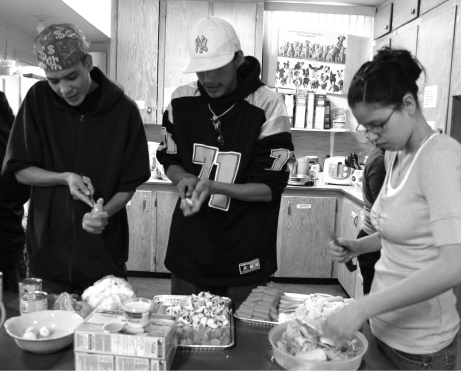

“Can you set up some tables for a display, too?” I asked. “I have a lot of purses I’d like to show.” I left the sewing machine and the purses on the table and ran downstairs to help Mrs. B. and Lila with the feast. Two of the reporters followed me and took pictures of me and the other people helping. They asked everybody questions while we chopped vegetables and mixed frozen juice.

Mrs. B. was stirring a huge pot of chili on the stove, and Lila was talking quickly, firing off commands to everyone within earshot. “Lacey, peel those carrots and cut them into sticks,” she said, as soon as she saw me. “Trisha, get back here. This lettuce needs to be torn into smaller pieces. Think bite-size. Where are those boys? We need set-up down here, too.

“Come on! Hurry up! Eh stu! They’ll be here soon, and we have to be ready.”

Everyone pitched in to help prepare for the celebration.

I smiled as I cut the carrots and watermelon. Lila sounded as bossy as I had sounded last night. I felt so excited that the African grandmothers were coming that I wasn’t even tired from staying up late. I couldn’t believe they were really coming. I never thought it would turn out like this. I just thought I could raise a little money to help them, and now they would be here, in real life. Mrs. B. told me they had never been to a small place in Canada before. They had been only to big cities like Calgary and Toronto. It would be such an honor to meet them. This was going to be my best day ever.

I was nearly finished the chopping when Kelvin came in. Even though we were almost related, I still didn’t want to look at him. No matter how nice he was being lately, I was still mad about how he wrecked my flowers and about how he treated Angel. He came close beside me and touched my arm lightly. “Come. Follow me,” he said quietly. When I hesitated, he took my hand gently, like a brother. “I want to show you something,” he said.

I followed him up the main stairs and outside the church. He led me past the brand new basement windows and the wall that had been freshly painted to cover up the bad words. He led me to the back of the school, where the elders had told the boys how to set up the school’s tepee. There was a flowerpot overflowing with large pink flowers and delicate blue and white ones hanging from the fence, and on the ground near the entrance to the tepee was a clump of sweet grass with its purplish spring flowers. Other native plants, such as pale purple crocuses and clumps of wild chives with ball-like purple flowers were planted around the fence. The plants were even prettier than the ones that he had wrecked. Kelvin didn’t say anything. He just stood there and looked down, showing his respect for me.

“You? You did this?”

His black hair fell over his face when he nodded. “I had help,” he said.

“Kelvin? You?” I asked again, in disbelief. He nodded again. “But how?”

“The old lady who has that big garden, the one who brings vegetables to Sequoia? I fixed her car the other day. She wanted to give me twenty bucks. I didn’t want any money, but since she had a lot of nice flowers, I asked if I could have a few of them instead. She gave me that big pot full of flowers,” he said, nodding towards the pot hanging on the fence. “This other stuff, me and the guys just dug up and stuck in the dirt. I don’t know if they’ll live, but if they get enough water, maybe they will. They might even come back again next year, too, without planting them over again.” He spoke slowly, and mostly kept his head down and scuffed his shoe back and forth in the grass. He looked embarrassed, rather than proud, of what he’d done.

I didn’t know what to say. There were so many thoughts in my head. Kelvin had done something good? It couldn’t be. It had to be a trick. He must want something. Then I remembered my grandmother’s voice saying that sometimes thinking with your head makes you mixed up. She had told me to listen to my heart. I also remembered her telling me about the white buffalo calf and how it would bring a time of peace and harmony. Was the legend true?

Kelvin lifted his head and looked at me. The hair fell from his eyes without that proud flick he liked to do. His eyes weren’t hard and angry – they were as gentle as Angel’s.

“We have to get along, Lacey. We’re family.”

But he was my enemy. The one who yelled at my sister and bullied her, the one who pointed his finger at me and told me to stay out of things. Replacing the plants he had destroyed wouldn’t change that. He would still be mean, still be a bully.

“I know you think I smashed your flowerpots, but I didn’t. The police don’t believe me either. No one believes me – no one except Angel. But I didn’t do it, and that’s the truth,” he said. “Ever since I stole that car, everyone is against me. They finger me every time anything happens. They want to prove I’m just like my father, but I’m not. I’m a different person.”

“But if you didn’t wreck them, why did you…”

“I did it for you and for Angel.” He looked down at the ground again. “I wanted to make something pretty, something good.”

I just stood there looking at the flowers and not really believing that Kelvin could do this.

“It’s like your dad told me. I have to prove myself, in small ways, then in big ways. Over and over, he said. He said I’d have to keep doing good things, and doing good things until people started believing in me, trusting me.” He scuffed the grass some more. “I’m trying, you know? Because I want to be a good partner for Angel and a good father for Kayden. Sometimes I still get it wrong, but I’m trying to be a better person. Step by step, you know?”

“But your finger was all black, and you were mad that you failed math…” I looked at his hands, a mix of grease from working at the garage and dirt from planting. Could I have been wrong? Had it been dried grease and not paint on his finger that day?

“It wasn’t me,” he said. I stood quietly looking at him, and my heart understood.

“I believe you,” I said, then I put my arms around him and hugged him like a brother. He hugged me back, but just for a second.

“It’s the white buffalo calf,” I said quietly, letting the words in my mind come out. “It’s just like Kahasi said.”

Kelvin squinted his eyes at me. “You mean that white buffalo at the zoo?”

I nodded. “Kahasi told me how it’s a sacred animal,”

“I know about that. Mrs. B. is getting a bus or a big van to take whoever wants to go to see it. Maybe you could go, too.”

“Really? There’s a bus going to the zoo?” I wanted to go, but even more, I wanted Kahasi to go. Maybe I could get her on that bus.