These days, hops get all the credit for imparting beer with heady flavors and aromas—and most brewers happily let grains fade into the background. But grains are the real brains behind the beer—the substance responsible for color, mouthfeel, and body, and provides the sugars that yeast produces into alcohol.

Many different types of grain are used to make beer—wheat, spelt, oats, corn, and rice, just to name a few examples—but malted barley is by far the most widely used. In fact, nearly all beers, including wheat beer and those made with corn and rice, use malted barley as the primary fermentable sugar (the only exception being gluten-free beer, which uses sorghum as the primary starch).

What is malted barley? Malting is a process that primes a grain for brewing by activating starches and sugars, which, when mixed with hot water, will ultimately form the base of beer. Nearly any grain can be malted, so “malt” and “barley” are not synonymous terms. Malted wheat is used to make wheat beer and malted rye for rye beer, for example. But in general, when brewers refer to “malt,” they usually mean malted barley.

WHY MALT?

What’s the point of malting grain in the first place? Raw, unmalted grains contain starches, but they are locked up inside the grain—try steeping unmalted barley in hot water and not much happens. Malting changes this so that the grain readily gives up complex carbohydrates and starches when used in brewing. It’s a three-step process that includes steeping, germination, and drying.

Malts caramelize to produce a sweet aroma

Illustration: Tyler Gross

Raw grains are first submerged off and on for about two days, during which time they absorb water, increasing their overall moisture content from roughly 10 to 45 percent. The swelled grains then undergo germination, in which protein and carbohydrates break down, opening the starch reserves. This process takes about four days and is facilitated with warm, humid air passing over the grain bed. Then comes the drying phase, which halts germination (if the grain were allowed to continue, it would sprout into a fully realized plant).

The amount of drying depends on how the grain will be used for beer. So-called base malts—the standard golden-colored grains used in most brewing—are kiln-dried at around 190°F for several hours. Specialty malts on the other hand—ones used for more robust flavors and darker beers—are dried at higher temperatures for extended periods of time so that they caramelize and roast.

Different grain for brewing beer

Photo: Shutterstock: CCat82

MONSTER MASH!

Here are some short definitions of what goes into making a malt mash:

GRAIN BILL

Also called malt bill or mash bill, the grain bill is the list of grains included in the mashing process when hot water is added to malt to extract fermentable sugars. A grain bill almost always includes a high proportion of malted barley and sometimes other grains like rice, corn, and wheat.

MASHING

This is the first step in brewing. Hot water is added to milled malt to extract flavors and sugars. The hot grain and water slurry is allowed to steep and rest at certain temperatures and for exact periods of time in order to activate enzymes in the grain, which convert unfermentable starches to fermentable sugars.

WORT

This is the liquid extracted from the mash. It is sweet and full of sugars, which will eventually ferment the wort into beer, creating alcohol and carbon dioxide along the way.

A brewery’s mash tun copper tanks

Photo: Alamy: Lucas Vallecillos

MALT MAKES ITS MARK

So how does malted grain influence beer? In nearly every way possible! Malt is the primary culprit for determining a beer’s color, body, mouthfeel, and ABV. It also adds flavor and some aroma.

COLOR Unless fruit or some other coloring agent is added to beer, malt is how beer gets its color. Color is directly related to how much and which kinds of malt are used. For example, light beers use light, straw-colored base malts, while dark beers incorporate specialty dark malts. Brown ales use lighter roasted malts; red ales use caramel malts. But note that in darker beers, dark malt is not the only malt used, just an important player in the overall grain bill. Also, dark beer does not equal strong beer! Some of the strongest beers in the world are light in color, while some of the lightest are dark.

BODY AND MOUTHFEEL Beer has a sweeping range of textures, from watery and insipid to velvety, thick, and coating. And nearly all of it has to do with sugars—both fermentable and unfermentable—and proteins extracted from the grain bill. Think of body as a general descriptor of the thinness, thickness, or robustness of a beer, while mouthfeel can be used to describe specific physical sensations, such as dryness, astringency, warmth, and carbonation. On a very basic level, full-bodied beers like barleywine are brewed with more malt than light-bodied beers. Light-bodied beers like pilsners use less grain for fewer fermentable sugars.

ALCOHOL Closely linked to body and mouthfeel is ABV. This indicates the total volume of liquid that is made up by alcohol. Alcohol content is determined by the amount of fermentable sugars that the yeast ferment (chew up) and turn into (spit out). High-alcohol beers are typically made with an abundance of fermentable sugars (more grain or added adjuncts), making them boozy with a warming mouthfeel. Low-alcohol beers are the opposite, usually light on the palate, brisk, and refreshing, though there are some exceptions to these generalizations.

Original illustration by Skatin Chinchilla

BARLEY

Malted barley is by far the grain most often used to make beer. It forms the base for every style, from the lightest pilsner to the darkest imperial stout. Nearly any grain can be malted, but barley is synonymous with this technique.

Malt has a robust husk that doubles as a protectant against damage from rough handling during germination and as a filtration medium in the brewhouse, naturally filtering the wort for a bright, clean liquid for efficient fermentation.

Barley can be classified in many ways. The most common classifications in beer-speak are two-row and six-row. (Others include winter or spring, and malting or feed.) Two-row and six-row refer to the arrangement of the individual grain kernels on a head of barley, and how many are fertile. Two-row barley appears to have only two rows of grain, one along each side of the head, while six-row contains a mutant gene producing six rows of grain along the length of the head.

Brewers use both two- and six-row barley for brewing, but how do these differences translate in the glass? In general, six-row barley has higher protein and more enzymes than two-row, which has a more uniform grain size and higher starch content, making it optimal for grist production when milled in the brewhouse. However, economically, six-row is a superior product for farmers, because the carbohydrate yield is much higher in a single crop. Flavor-wise, brewers prefer two-row because it supposedly creates a malty, full-flavored beer, while some say six-row produces gritty, grainy beer.

Depending on the amount of drying and roasting, malt can be classified into a handful of categories, such as:

BASE MALTS are the everyday brewing malts and include pale malt, pilsner malt, and Vienna malt, as well as several others. They can also include non-barley malts like malted wheat, spelt, and rye. Base malts can be named for their structure (two-row, six-row), the location where they were harvested (Moravia in the Czech Republic), the type of beer they’re used in (pilsner malt), or their barley variety (Marris Otter). This leads to a breadth of malt variety for brewers. Base malts make up at least 50 to 100 percent of any beer’s grain bill.

BARLEY TYPES

The two different types of barley used in brewing beer may look very similar, but they can produce very different flavors.

TWO-ROW

Two-row barley creates a malty, full-flavored beer

Original illustration by Skatin Chinchilla

SIX-ROW

Six-row barley purportedly produces a gritty, grainy beer

Original illustration by Skatin Chinchilla

CRYSTAL MALTS add color and sweetness to beer and are usually named based on a color scale of light to dark. Lighter crystal malts give sweetness, while darker ones add toffee-ish, burnt caramel flavor and bittersweetness. The extremely light ones are called dextrin malts, which contribute a thick, robust mouthfeel and full body to beer.

ROASTED AND DARK MALTS are dried at high temperatures for a prolonged period, giving a dark color and roasty flavor. There is a wide variety of styles, but the three most common, in order of increasing degree of roast, are chocolate malt, black patent malt, and roast barley. Dark malts give huge flavor, aroma, and color even when used in small quantities. The highest percentage for dark malts is usually about 10 percent of the overall grain bill.

OTHER MALTS AND ADJUNCTS include malted wheat, spelt, and rye, which take on much smaller supporting roles in the overall grain bill. Adjuncts include corn and rice, common in many North American and Asian beers. (These are covered in detail below.) Adjuncts can also be added along with fermentable sugars like honey, pumpkin, potatoes, and other starchy vegetables.

A brewer checks in on his kettle

Photo: Stocksy: SEAN LOCKE

GRAIN-FREE AND GLUTEN-REDUCED BEER

If it isn’t made with grain, is it actually beer? That’s a question that’s been hotly debated for years. But beer made with no-gluten grains like oats and sorghum are the safe option for people with celiac disease.

Photo: Alamy: George Fisher

For a long time, most gluten-free products were pretty vulgar. That was especially true of gluten-free beer. But the landscape has changed over the past several years and some gluten-free options are now downright delicious.

What’s the problem with gluten anyway? Those with celiac disease can’t easily digest the protein known as gluten, one of the many proteins found in most grains used for brewing. In these folks, gluten causes paralyzing stomach pains and massive sickness, which makes consuming beer, pasta, or bread next to deadly.

The “gluten-sensitive” debate continues to rage. This includes people who haven’t been diagnosed with celiac disease, but have some level of discomfort when consuming gluten. For drinkers hoping to reduce their gluten intake or minimize gluten sensitivities, “gluten-reduced” or “crafted to reduce gluten” beers are a godsend.

Gluten-reduced beers are made like other beers, but an enzyme is added during the fermentation stage. This efficient enzyme reduces the gluten content down to fewer than twenty parts per million, below the Codex Alimentarius standard for gluten-free products. But gluten-reduced beers can never be labeled strictly “gluten free,” because they’re derived from grain-based recipes.

For celiacs, there is no spectrum of gluten—it’s either gluten free or it isn’t.

TRY: STONE DELICIOUS IPA, WICKED WEED GLUTEN FREEK, BREWDOG VAGABOND PALE ALE, ALPINE BEER COMPANY EXPONENTIAL HOPPINESS*

A multitude of beer is on offer at the Mikkeller Bangkok bar

Brewery: Mikkeller

OTHER GRAINS

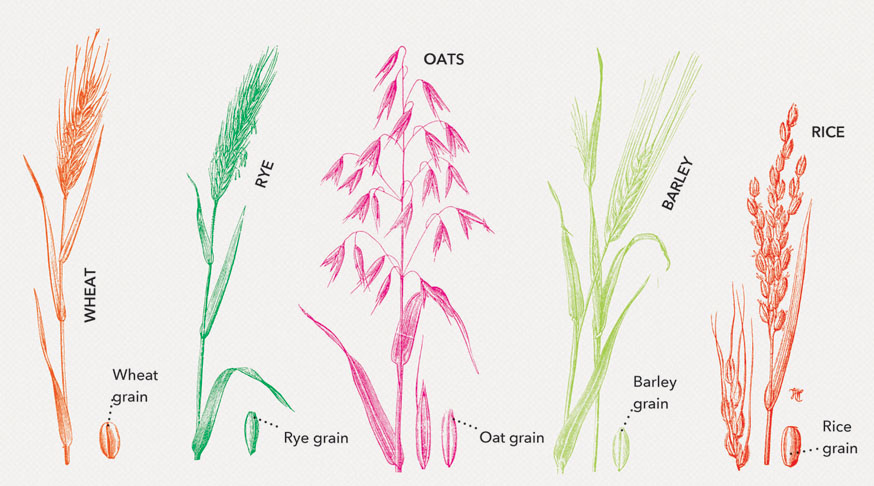

Although barley is predominantly used in brewing beer, a number of alternative grains are also used.

TURN UP THE WHEAT

Behind barley, wheat is the second most popular grain among traditional and craft brewers. But, unlike barley, it isn’t always malted before entering the mash. In fact, many wheat beer styles use raw or unmalted wheat in the grain bill.

The most famous wheat beer styles are the weissbiers of Germany and witbiers of Belgium. (Weiss and wit mean “white” in their respective languages, but the etymology is derived from the same source as “wheat.”) These styles are copied in the US with a noticeable hop presence and often a fruit component like coriander and orange peel (as traditionally used in Belgium).

Wheat lends beer a touch of acidity and a creamy mouthfeel. That acidity makes it perfect for light dishes and thirst-quenching warm weather.

TRY: ALLAGASH WHITE, SCHNEIDER WEISSE ORIGINAL, THE BRUERY WHITE CHOCOLATE

YOU SPELT IT WRONG

Spelt is an ancient variety of wheat that’s been used in brewing for millennia. It’s largely forgotten today, but is making a comeback as a niche grain in some brewing circles. It often adds an earthy aroma and provides similar flavors and textures as wheat, but with a softly toasty, chewy quality that isn’t always present in regular wheat beers. In German, spelt is called dinkel and a dinkelbier—not to be confused with dunkelbier—is an ale made with spelt.

Nowadays, spelt is most frequently used in saisons to provide a rustic grain quality and a fuller, fluffier mouthfeel. It’s often used in conjunction with barley, oats, and other grains for complexity and textural depth. It does particularly well with hoppy beers, providing a dry, tight background for the hop aromas to shine.

TRY: HOPWORKS SURVIVAL 7-GRAIN STOUT, BLAUGIES SAISON D’EPEAUTRE

RYES UP

Malted rye adds spiciness, dryness, and a smooth, rounded mouthfeel. It contributes color, too, usually a reddish to light-brown hue. The proportion of rye used in modern beer is typically below 20 percent of the entire malt bill, meaning 80 percent is still made up of malted barley or other grains (wheat is common). Rye is high in protein and causes the mash to become gummy and sticky if used in too high a percentage.

Roggenbier is a historic German rye beer. (Roggen is German for rye.) Roggenbiers were nearly extinct after the Reinheitsgebot forbade the use of any grain but barley in beer. But over the past few decades, a renewed roggen interest has emerged, and the style is alive and well once again. Modern roggenbiers are brownish to dark red in color, about 5 or 6 percent ABV, and robust and warming with a spicy, rye bread–like flavor.

Some American brewers make roggenbier, but today the most popular form of rye beer is the rye pale ale or rye IPA. (Sometimes cheekily called Rye-P-A.) This hybrid style has all the hoppiness of IPA with a peppery, dry kick from rye. Like roggenbiers, they are reddish to rust in color, with big aromas of bread, pine, and citrus.

Another oddball rye beverage is kvass. This low-alcohol Eastern European drink is made from a slurry of water and leftover dark-grained rye bread that has already been baked and gone stale. It was traditionally used to stretch stale bread further and even purify water as the resulting (low-percentage) alcohol kept microorganisms at bay. Kvass isn’t technically a beer, but it received experimental interest among American brewers, such as Goose Island, Jester King, and Fonta Flora.

TRY: BÜRGERBRÄU WOLNZACHER ROGGENBIER, FIRESTONE WALKER WOOKEY JACK BLACK RYE IPA

Photo: iStock: RuslanDashinsky

OATSMOBILE

Did you know that oatmeal has been used in beer for centuries? The most familiar example is creamy oatmeal stouts of the UK. Like rye, oats can gum up the mash, so most brewers prefer to keep them below 10 percent of the overall malt bill. They add a distinctive creamy flavor, full-bodied mouthfeel, and decidedly turbid appearance to beer.

Besides oatmeal stouts, oats are increasingly used in American pale ales and IPAs as a way to boost body and mouthfeel without adding extra booze. In fact, flaked oats are now a primary distinctive ingredient in many New England and Northeast-style IPAs. They are high in beta glucans, which add a soft, elegant edge, and they impart a hazy “juicy” quality that’s all the rage today.

TRY: SAMUEL SMITH OATMEAL STOUT, TIRED HANDS HOPHANDS

UNI-CORN

Corn is a dirty word when it comes to beer. The crop is a so-called adjunct, adding cheap fermentable sugar but little taste or body. In fact, beer made with corn is lighter in color, flavor, and mouthfeel than beer made with all malted grain—and often it’s used for just those purposes (to make a lighter beer). It is most common in American adjunct lagers like Budweiser, Coors, and Miller High Life, where it may be added in many forms, including grits, flaked corn, or corn syrup.

Corn was originally used in American beer to soften the hard, astringent, grainy character of North American six-row barley. Nineteenth-century brewers substituted the plentiful low-protein corn crop for a percentage of malted barley (around 20 percent) to create a lighter, crisper beer like the German pilsners they were accustomed to in Bavaria.

Today, corn is shedding some of its taboo status. It’s long been the traditional grain used in bourbon, which is experiencing a serious revival among cocktail and spirits enthusiasts (including many brewers). And whether ironically or not, some small American beer makers are embracing corn as a no-shame ingredient in brewing, using it in hoppy pilsners and other lagers without fear of backlash from consumers.

TRY: MILLER HIGH LIFE, STILLWATER CLASSIQUE

Original illustration by Skatin Chinchilla

GLORIOUS GRAINS

Here are some of the types of grain that are malted to make beer:

Photo: Alamy: Quagga Media

MR. RICE GUY

Like corn, rice is used as an adjunct to lighten and dry out beer. It’s the primary adjunct in Asian-style pale lagers, made throughout Asia and particularly favored in South Korea, Thailand, and Japan. One of the most common is Asahi Super Dry, marked by a pronounced dryness from its high proportion of rice in the mash. The beer set off Japan’s so-called Dry Wars of the 1980s when breweries pushed for further lightness of body and crispness of flavor in their beers.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that rice has now made its way into American styles, largely as a novelty ingredient. The grain adds a crisp, clean finish without imparting much flavor. It simultaneously lightens the body and increases the ABV.

TRY: ASAHI SUPER DRY, THE BRUERY TRADE WINDS TRIPEL

Photo: Alamy: Steve Cukrov