Have you ever struggled to make a decision, perhaps agonizing over how to make the right choice, or become trapped in analysis paralysis, overwhelmed by all the options and unable to make a choice and move forward? Making the right choice used to be a huge stumbling block for me, as I’d often get stuck in a trap of trying to make perfect decisions. At the time, I couldn’t see that as the real problem; but looking back now, it’s clear.

I fell in the perfect-decision trap a few years ago when I returned to work following maternity leave with Elle. Heading back to the office, I was determined to exclusively breastfeed, even if that meant pumping for hours on end. After a few weeks, though, pumping became a dreaded chore, and I came home depleted at the end of every day. I grappled with the decision of whether to continue, but I couldn’t get past the fact that I wanted to have it all: exclusively breastfeed and not burn out in process. I felt a heaviness in weighing the options, and I was convinced there had to be a way to have both. I felt stuck, incapable of making the decision because I was refusing to acknowledge the pros and cons. But that’s the thing. Every decision comes with a set of trade-offs. Looking back, I wish I had understood how to analyze the benefits and drawbacks and then make the best possible decision, rather than feeling paralyzed trying to make the perfect one.

In my attempt to exclusively breastfeed, I was trading time and a good amount of my sanity, yet I had zero awareness or acknowledgment of the inherent outcomes. In my mind, it seemed that there must be a perfect decision, one that would allow me to exclusively breastfeed, and work, and not spend hours pumping. Now, the point here isn’t whether exclusive breastfeeding is good or bad, nor is it which option I should have chosen. The point is that there simply is no decision without trade-offs, no “balance” disguised as perfection.

Even if you’ve never been faced with this specific dilemma, my guess is you can recall a decision in your own life when you couldn’t see or didn’t want to recognize the give and take. Recently a friend of mine decided to relocate for work, but he quickly became frustrated by the process of moving—trying to rent his old apartment, find a new place, and handle all the hassles of packing and unpacking. The problem wasn’t the move. The problem was that he’d made a decision hoping for a perfect world, one where he could move and not deal with any of the hassle. He hadn’t considered and acknowledged the trade-offs, which cost him both time and frustration in the long run.

Permission to Satisfice

So if perfect solutions don’t exist, what exactly are you supposed to do? You need to satisfice. No, that’s not a typo. While satisficing sounds like a made-up word, it is a very real thing. It’s actually a combination of the words satisfy and suffice, coined by economist, political scientist, and cognitive psychologist Herbert Simon. Simon studied how humans make decisions, and he came to the conclusion that we can find either “optimum solutions for a simplified world, or satisfactory solutions for a more realistic world.” Meaning that when the set of options are simple, you can indeed make a “perfect” choice. But when the set of options are complex, when there are countless variables, connections, and complexities, the best you can do is make a satisfactory choice. Not perfect. Just the best possible given the realistic alternatives.

Unfortunately, when it comes to making decisions, or choices, or the elusive quest for balance, it seems many of us still get stuck trying to find optimum solutions. But that’s the problem because we don’t live in a simplified world. Instead we live in one that is highly complex and connected. One where every decision contains within it many exchanges. One that requires not optimum solutions but satisfying, satisfactory solutions, which tend to counter a lot of what we often believe when it comes to decision-making. Sure, it seems as though agonizing over the perfect choice is a good idea, but research shows that maximizing, or trying to optimize the best choice, leads to all kinds of negative outcomes. For example, people who get stuck maximizing tend to be less happy and less optimistic, have lower self-esteem, and often end up regretting their decisions after making them. People who maximize also tend to get sucked into social comparison more often, and they are less confident and less satisfied with their own choices. Research also shows that people who try to maximize tend to feel an undeniable urge to do an exhaustive search of options before making a decision. For example, someone maximizing while shopping for shoes might visit every possible store, engaging in exhaustive comparison and putting a ton of time and energy into finding the perfect option. Ironically, that same person is likely to feel less satisfied with his or her choice in the long run.

On the other hand, studies show that people who satisfice make decisions based on just a few criteria that matter to them, content in finding solutions that are good enough given the circumstances. For example, someone satisficing might shop for shoes based on a set of criteria such as the shoes be blue, comfortable, and made to last. Once the person finds the shoe that meets these criteria, they are then satisfied and stop searching. They don’t keep shopping in the hope of finding an even better option. They select what is good enough, get what they want, don’t spend unnecessary time or energy making decisions, and are usually happier with their choices in the long run. Free from agonizing and analysis paralysis, satisficers simply make the best possible choice, take imperfect action, and move forward.

It’s All about Trade-Offs

The good news here is that being a maximizer isn’t a personality trait, and someone who maximizes can start to satisfice by learning a new set of skills. The first step in the process is acknowledging that there will never be a perfect choice or decision. Satisficing is simple: it’s weighing the factors, acknowledging the trade-offs, and then making the best choice possible. For you. At that moment. Then it’s about giving yourself permission to accept the trade-offs.

That “for you” part means that your best possible decisions aren’t necessarily going to be the same as someone else’s, because they will be made based on your values, your preferences, and how you define feeling good. Similarly, that “right now” part means that what’s best now might not be best down the road. Trade-offs can change over time. As your life circumstances change, and things shift and evolve, so, too, will your best possible decisions. This takes the pressure off, allowing you to take a deep breath and let some things go. Satisficing gives you the opportunity to reframe that whole elusive concept of balance. Instead of trying to do it all, all at once, you embrace the set of trade-offs, make the best possible decision for you, and move forward. In the end, you are actually able to optimize your life simply by satisficing.

The beauty of satisficing is that you’re not ignoring the impact of the choices you make, throwing caution to the wind, or making decisions without thought or consideration. With satisficing, you don’t have to feel as though you’re settling or accepting mediocrity. It’s a strategy to embrace the context of your current life instead of fighting against it, arriving at the very best possible solution without driving yourself crazy, or setting yourself up to feel like a failure. Another benefit? Optimizing by satisficing allows you to reframe “let good enough be good enough” as the objective, rather than seeing it as settling. Because good enough is good enough. It’s really all there is, anyway. Satisficing allows you to identify what’s truly essential and then to make the best possible choice.

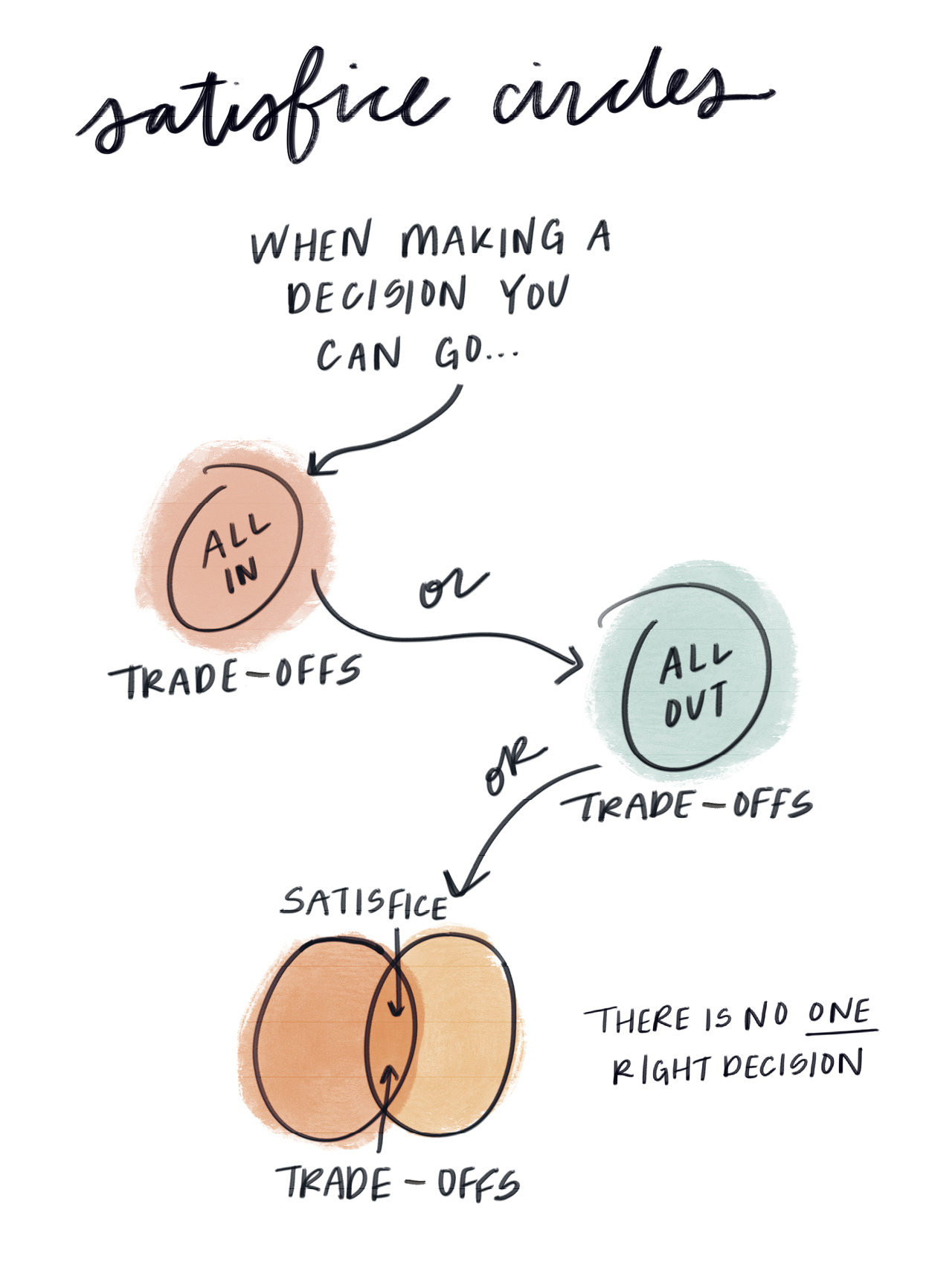

Make It Happen Exercise: Satisfice Circles

This exercise is designed to help you identify the trade-offs involved in any decision, which will allow you to make the best possible decision based on your values, season of life, and definition of feeling good.

Select a Decision

Think about a decision you want to make. It can be something small, like figuring out how many minutes to exercise each day, or something big, like deciding if you should go back to school. Write down the decision at the top of a piece of paper.

All-In and All-Out Circles

Draw two large circles, slightly askew, on the paper. In the left circle, write out the case(s) for an all-in option. For example, exercising for 60 minutes every day or quitting your job to go back to school. This is your All-In circle.

Then in the right circle, write out all the extreme case(s) for the all-out option. For example, not exercising at all, or keeping your job and staying with the status quo. This is your All-Out circle.

Trade-Offs

Under the All-In circle, write a list of trade-offs for the case(s); that is, what will you have to give up or let go of to pursue this option. Then under the All-Out circle, write a second list of trade-offs necessary to reach this outcome. No need to overthink it; just go with whatever comes to mind first.

Satisfice

At the bottom of the paper, draw a set of overlapping circles. This overlap is your opportunity to satisfice. Write down as many options as you can think of in between the two extremes.

Consider the Options

Now, looking at the circles as a whole, ask yourself the following three questions.

Are the scenarios in the All-In circle worth the trade-offs?

This is an important question to ask, as it often reveals additional trade-offs that you may not have considered.

Are the scenarios in the All-Out circle worth those trade-offs?

Similarly, this question is helpful as it sometimes reveals additional trade-offs that may have not been considered.

Are there options in the Satisfice circle that represent a more satisfactory mix of trade-offs?

This step will allow you to see clearly that all options come with trade-offs; thus, the decision-making process becomes the act of selecting the mix that works best for you right now.

Make a Decision

Once you’ve considered the options and trade-offs, it’s time to make a decision. Again, there’s no right or wrong answer; nor is there a perfect solution. You might decide to go with a scenario in the All-In circle because, after considering the trade-offs, you decide it’s worth it. Similarly, you might decide to go with an All-Out option because you realize it’s worth those scenarios. Sometimes satisficing means keeping things the same, at least in the short term. You might also find that there are options within the overlapping circles you may have not previously considered. Or, with a few small tweaks, you can move an All-In or All-Out option into the satisfice circles, making it far more doable and sustainable.

As you repeat this exercise with various decisions, you’ll find that the process becomes easier and faster. In fact, you’ll most likely find that you no longer need to draw the circles because you’ll be able to weigh trade-offs in your head, make a decision, and move on without giving it a second thought. I do recommend, however, completing the exercise in full until the process becomes second nature.