Den grimme ælling

The ugly duckling has led a charmed existence over the past century and a half, alluded to in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, celebrated in Sergei Prokofiev’s music, and, less surprisingly, taken up in Walt Disney’s films. The story of the abject, despised bird has taken hold in many cultures, becoming one of our most beloved—and most reassuring—childhood tales. It promises all of us, children and adults, that we have the capacity to transform ourselves for the better.

Like many a fairy-tale character, the ugly duckling is meek and small, the youngest in the brood. A misfit out of place in the barnyard, in the wilderness, and in the domestic arena, he is unable to find a bond with other creatures. But, like Andersen himself as a youth, he is adventurous and determined, resolving to go out into “the wide world.” His metamorphosis into a beautiful swan has been evoked for generations as a source of comfort to those suffering from feelings of social isolation and personal inadequacy.

Small, powerless, and often treated dismissively, children are likely to identify with Andersen’s “hideous” creature, who may be unpromising but who also, in time, surpasses the promising. As Bruno Bettelheim points out in The Uses of Enchantment, Andersen’s protagonist does not have to submit to the tests, tasks, and trials usually imposed on the heroes of fairy tales. “No need to accomplish anything is expressed in ‘The Ugly Duckling.’ Things are simply fated and unfold accordingly, whether or not the hero takes some action” (Bettelheim, 105). Andersen suggests that the ugly duckling’s innate superiority resides in the fact that he is of a different breed. Unlike the other ducks, he has been hatched from a swan’s egg. This implied hierarchy in nature—majestic swans versus the barnyard rabble—seems to suggest that dignity and worth, along with aesthetic and moral superiority, are determined by nature rather than by accomplishment. Whatever the pleasures of a story that celebrates the triumph of the underdog, it is worth pondering the full range of ethical and aesthetic issues raised by that victory in a story that is read today by children the world over.

“The Ugly Duckling” was published with three other tales in a collection called New Fairy Tales. It sold out almost immediately, and Andersen wrote with pride about its success in a letter of December 18, 1843: “The book is selling like hot cakes! All the papers are praising it, everyone is reading it! No books of mine are appreciated in the way that these fairy tales are!” (H. C. Andersen og Henriette Wulff, I, 349)

It was so beautiful out in the country—it was summertime! 2 The grain was golden, the oats were green, and hay was piled in stacks down in the green meadows. A stork with long red legs was strolling around and chattering away in Egyptian,3 a language he had learned from his mother. All around the fields and meadows lay vast forests dotted with deep lakes. Yes, it was really lovely out there in the country! Right in the sunshine you could see an old castle4 surrounded by a deep moat with huge burdock leaves5 covering the stretch from the walls down to the water. The leaves were so high up that little children could stand upright beneath the largest of them. It was just as wild in there as in the densest forest, and that’s just where you could see a duck sitting on her nest. The time had come for her to hatch her little ducklings, but it was such a slow job that she was growing tired of it. There were hardly any visitors. The other ducks preferred swimming around in the moat to sitting under a burdock leaf just for the sake of a quack with her.

At last the eggs cracked open, one by one. “Cheep, cheep,” they all said. The egg yolks had finally come to life and stuck their heads out.

“Quack, quack!” said the mother duck, and the little ones quacked as best they could and looked around quickly from under the green leaves all about. The mother let them feast their eyes, for greenery is good for the eyes.

“The world is so big!”6 all the ducklings said, for they now had much more room than when they were curled up in an egg.

“Do you really think that this is all there is to the world!” their mother exclaimed. “Why, it stretches way past the other side of the garden, right into the parson’s field. But I’ve never ventured that far out. Well, you’re all hatched now, I hope.” And she rose from the nest. “Wait a minute! Not everyone is out yet! The biggest egg is still lying here. How much longer is this going to take, anyway? I’ve just about had it!” And she sat back down in the nest.

“Well, how are you getting on?” asked an old duck who had come to pay a visit.

“One of the eggs is taking so long to hatch!” said the duck on the nest. “It just won’t open. But take a look at the others—the loveliest ducklings I’ve ever seen. They all take after their father, the scoundrel! He never even comes to pay a visit.” “Let’s have a look at the egg that won’t crack open,” said the old duck. “I’ll wager it’s a turkey’s egg. That’s how I was once bamboozled. The little ones gave me no end of trouble, for they were afraid of the water—imagine that! I just couldn’t get them to go in. I quacked and clacked, but it didn’t do any good. Let’s have a look at that egg. Oh, yes, that’s a turkey’s egg—you can bet on it! Leave it alone and start teaching the others to swim.”

“I think I’ll sit on it just a little longer,” said the duck. “I’ve been sitting so long that it can’t hurt to sit a bit more.”

“Suit yourself!” said the old duck, and off she waddled.

Finally the big egg began to crack. The little one said, “Cheep, cheep!” as he tumbled out, looking ever so big and hideous.7 The duck took a look and said: “My, what a great big duckling that is! The others don’t look like that. But it couldn’t be a turkey chick, could it? Well, we shall soon see. Into the water he goes, even if I have to push him in myself!”

The next morning the weather was gloriously beautiful, and the sun was shining brightly on all the green burdock leaves. The mother duck came down to the water with her entire family and splash! She jumped right in. “Quack, quack,” she said, and one after another the ducklings plunged in after her. The water closed over their heads, but in an instant they were back up again, floating along serenely. Their legs paddled along on their own, and now the whole group was in the water—even the hideous gray duckling was swimming right along with them.

“He’s not a turkey, that’s for sure,” said the duck. “Look how well he uses his legs and how straight he holds himself. He’s my own little one all right, and he’s quite handsome, when you take a good look at him. Quack, quack! Now come along with me and let me show you the world and introduce you to everyone in the barnyard. But pay attention and stay close to me so that nobody steps on you. And make sure you watch out for that cat.”

And so they made their way into the duck yard. It was terribly noisy there, because two families were fighting over an eel’s head. In the end, the cat got it.

“You see, that’s the way of the world,” said the mother duck, and she licked her beak, because she would not have minded getting the eel’s head. “Come now, use your legs and look sharp,” she said. “Make a nice bow to the old duck over there. She’s the most genteel of anyone here.8 She has Spanish blood, that’s why she is so plump. And can you see that crimson flag she’s wearing on one leg? It’s extremely lovely, and it’s the highest distinction any duck can earn. It’s as good as saying that no one is thinking of getting rid of her. Man and beast are to take notice! Look alive, and don’t turn your toes in! A well-bred duckling turns its toes out, just like its father and mother . . . That’s it. Now bend your necks and say ‘quack!’ ”

They all obeyed. But the other ducks there looked at them and said out loud: “There! Now we have to deal with that bunch as well—as if there weren’t enough of us already! Ugh! What a sight that duckling is! How can we possibly put up with him as well?” And one of the ducks immediately flew at him and bit him in the neck.

“Leave him alone,” said the mother. “He’s not doing any harm.”

“Yes, but he’s so gawky and odd-looking,” said the one that had pecked him. “We can’t help picking on him.”

“What pretty children you have, my dear!” said the old duck with the flag on her leg. “All but that one, who didn’t turn out quite right. Too bad you can’t start over again with him.”

“That’s impossible, Your Grace,” said the duckling’s mother. “He may not be handsome, but he’s so good-tempered and he can swim just as beautifully as the others—I dare say even a bit better. I think his looks will improve when he grows up, or maybe in time he’ll shrink a little. He was in the egg for too long—that’s why he isn’t quite the right shape.” And then she stroked his neck and smoothed out his feathers. “Anyway, he’s a drake, and so it doesn’t matter as much,”9 she added. “I feel sure he’ll turn out strong and be able to take care of himself.”

“The other ducklings are charming,” said the old duck. “Make yourselves at home, my dears, and if you should find anything that looks like an eel’s head, you can bring it over to me.”

And so they made themselves at home.

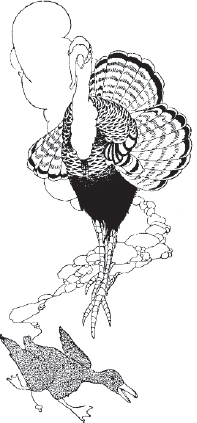

The poor duckling who had been the last to crawl out of his shell and who looked so hideous got pecked and jostled and was teased10 by ducks and hens alike. “He’s just enormous!” they all clucked. And the turkey, who had been born with spurs and who fancied himself an emperor, puffed himself up like a ship in full rigging and went straight at him. Then he gobble-gobbled until he was quite red in the face. The poor duckling didn’t know where to turn. He was quite upset at looking so unattractive and becoming the laughingstock of the barnyard.

That’s how it went the first day, and things only got worse from there. The poor duckling was picked on by everyone. Even his own brothers and sisters were cruel to him and kept saying: “Oh, you ugly creature, if only the cat would get you.” His mother said: “If only you were far away!” The ducks nipped at him,11 the chickens pecked him, and the maid who had to feed the poultry kicked him with her foot.

At last, he ran off and flew over the hedge, making the little birds in the bushes swarm into the air with fright. “They are afraid of me because I am so hideous,” he said. But he closed his eyes and kept moving until he reached some marshes12 where wild ducks lived. He stayed there all night, feeling utterly tired and dejected.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

Alone in the world, the duckling leaves the barnyard and makes his way to marshes, where he will meet wild ducks. Like many of Andersen’s characters, he must fend for himself in the “wide world.”

In the morning, when the wild ducks flew up into the air, they stared at their new companion. “What kind of duck could you possibly be?” they all asked, looking him up and down. He bowed his neck in their direction and greeted them as best he could.

“You really are nasty-looking,” said the wild ducks, “but we don’t care as long as you don’t try to marry into our families.” Poor thing! He wasn’t dreaming about marriage.13 All he wanted was a chance to lie quietly among the rushes and drink a little marsh water.

After he had been there for two whole days, a couple of wild geese,14 or rather two wild ganders (for they were male), came along. They had not been out of the egg for long and were very frisky.

“Look here, old pal,” one of them said to the duckling. “You are so hideous that we rather like you. Why don’t you join us and become a bird of passage? Not far off in another marsh there are some very nice, sweet wild geese, none of them married, and they all quack beautifully. Here’s a chance for you to get lucky, as hideous as you are.”

“Bang! Bang!” Shots suddenly rang out overhead, and the two wild geese fell dead into the rushes. The water turned red with their blood.15 “Bang! Bang!” More shots—and flocks of wild geese rose up from the rushes. Then shots rang out again. It was a big hunt, and the hunters had surrounded the marsh. Some of the men were even hidden in tree branches that stretched far out over the rushes. Blue smoke from the guns rose like clouds over the dark trees and hung low over the water. Hounds came bounding through the mud—Splish, Splash! Reeds and rushes bent every which way. How they terrified the poor duckling! He was trying to hide his head under his wing when he suddenly became aware of a fearsomely large dog with lolling tongue and grim, glaring eyes. It lowered its muzzle right down to the duckling, bared its sharp teeth and—splish, splash—went off again without touching him.

“Thank goodness,” the duckling sighed with relief. “I’m so hideous that even the dog can’t be bothered to bite me!”

So he lay there quite still, while bullets whistled through the reeds and rushes, and shot after shot blasted through the air.

By the time the noises had died down, it was late in the day. But the poor young duckling didn’t dare get up yet. He waited quietly for several hours, and then, after taking a careful look around him, he fled the marsh as fast as he could. He scrambled over meadows and fields, but the wind was so strong that he had trouble making any progress.

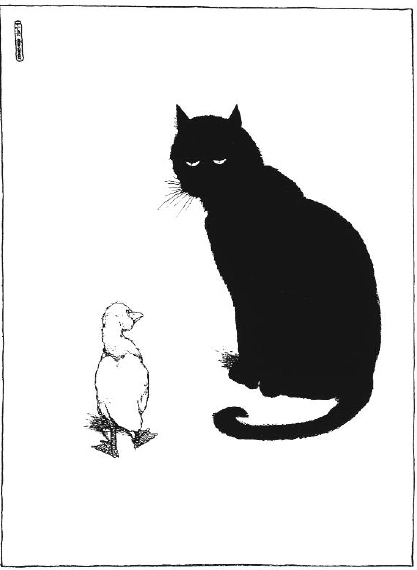

W. HEATH ROBINSON

The ugly duckling is dwarfed by the cat, whose minimalist but expressive eyes suggest deep suspicion and skepticism

Toward evening, he reached a small rundown cottage that was in such poor repair that it remained standing only because it could not figure out which way to collapse first. The wind blew so powerfully around the duckling that he had to sit on his tail to keep from being blown over. Soon the wind grew even fiercer. The duckling noticed that the door had come off one of its hinges and was hanging at an angle that allowed him to sneak into the house through a crack, which he did.

An old woman was living in the cottage with her tomcat and hen. 16 The tomcat, whom she called Sonny, could arch his back and purr. He even gave off sparks, if you stroked his fur the wrong way. The hen had such short legs that she was called Chickabiddy Shortlegs. She was a good layer of eggs, and the old woman loved her so much that she was like a daughter.

First thing in the morning the tomcat and hen noticed the strange duckling, and the cat began to purr and the hen began to cluck.

“What’s all the fuss about?” asked the old woman, looking around the room. But her eyes weren’t very good, and she took the ugly duckling for a plump duck that had strayed from home. “My, what a find!” she exclaimed. “I shall be able to have some duck eggs soon, as long as it’s not a drake! We’ll just have to wait and see.”

And so the duckling was taken on trial for three weeks, but there was no sign of an egg. Now the tomcat was master of the house, and the hen was mistress, and they always used to say: “We and the world,” for they fancied that they made up half the world, and, what’s more, the better half too. The duckling thought that there might be two opinions about that, but the hen wouldn’t hear of it.

“Can you lay eggs?” she asked.

“No!”

“Well, then, hold your tongue, will you!”

The tomcat asked: “Can you arch your back, or purr, or give off sparks?”

“No!”

“Well, then, no one needs your opinion, especially with sensible people around to do the talking.”

The duckling sat in a corner, feeling quite dejected. Then suddenly, he remembered the fresh air and the sunshine, and he began to feel such a deep longing for a swim on the water that he could not help letting the hen know.

“What are you thinking?” said the hen. “You have far too much time on your hands. That’s why such foolish ideas come into your head. They would vanish if you were able to lay eggs or purr.”

“But it’s so lovely to glide on the water,”17 the duckling said, “and so lovely to duck your head in and dive down to the bottom.”

“Delightful, I’m sure!” said the hen. “Why, you must be crazy! Ask the cat, he is the cleverest animal I know. Ask him how he feels about swimming or diving. I won’t even give my views. Ask our mistress, the old woman—there is no one in the world wiser than she is. Do you think she likes to swim or to dive down into the water?”

“You don’t understand me,” said the duckling.

“Well, if we don’t understand you, I should like to know who does.18 It’s clear that you will never be as wise as the cat or the mistress, not to mention me. Don’t be silly, child! Thank your maker for the good fortune that has come your way. Haven’t you found a nice, warm room, along with a circle of friends from whom you can learn something? But you’re just stupid, and there’s no fun in having you here. Believe me, if I say unpleasant things, it’s only for your own good and a proof of real friendship. But take my advice. See to it that you start to lay eggs or learn how to purr or throw off sparks.”

“I think I’ll go back out into the wide world,” said the duckling.

“Go ahead,” said the hen.

And so the duckling departed. He dove down into the water and swam about, but no one else would have anything to do with him because he was so ugly. Autumn arrived, and the leaves in the forest turned yellow and brown. As they fell to the ground, the wind caught them and made them dance. The sky overhead had a frosty look. The clouds hung heavy with hail and snowflakes, and a raven perched on a fence,19 crying, “Caw! Caw!” because of the bitter cold. It gave you the shivers just to think about it. Yes, the poor duckling was certainly having a hard time.

One evening, during a splendid sunset, a large flock of lovely birds suddenly emerged from the bushes. The duckling had never seen anything so beautiful;20 the birds were dazzlingly white with long, graceful necks. They were swans. They made wondrous sounds, spread out their magnificent, broad wings, and flew away from these cold regions to warmer countries, to lakes that were not frozen. As the ugly little duckling watched them rise higher and higher up into the air, he felt a strange sensation. He spun round and round in the water like a wheel and craned his neck in their direction, letting out a cry that was so shrill and strange that he himself was frightened when he heard it. How could he ever forget those beautiful birds, those fortunate birds! As soon as he lost sight of them, he dove down to the very bottom of the waters, and when he surfaced, he was almost beside himself with excitement. He had no idea who those birds were,21 nor did he know anything about where they were off to, but he loved them as he had never loved anyone before. He was not at all envious of them. After all, how could he ever aspire to such beauty? He would be quite satisfied if the ducks would just have let him be among them. The poor, ugly creature!

The winter was cold, so very cold. The duckling had to keep swimming about in the water to keep it from freezing solid around him. Every night the hole in which he was swimming grew smaller and smaller. The water froze so solidly that the crust of the ice crackled, and the duckling had to keep his feet moving constantly to keep the water from freezing solid. Finally, he grew faint with exhaustion and lay quite still and helpless, frozen fast in the ice. 22

Early the next morning, a farmer walked by and saw the poor duckling. He went out on the pond, broke the ice with his wooden clog, and took the duckling home to his wife.23 There they revived him.

The children wanted to play with him, but the duckling was afraid they would hurt him.24 He started up in a panic, fluttering right into the milk bowl25 so that milk splashed all over the room. When the farmer’s wife let out a shriek and threw her hands up in the air, he flew into the butter tub, and from there into the flour bin and out again.

He was quite a sight! The woman shrieked again and chased after him with the fire tongs, and the children stumbled all over each other trying to catch him. How they laughed and shouted! It was lucky that the door was open. The duckling darted out into the bushes and sank down, dazed, in the newly fallen snow.

It would be dreary26 to describe all the misery and hardship the duckling endured in the course of that hard winter. When the sun began to shine warmly again, he was lying in the marsh among the reeds. The lark was singing—it was a beautiful spring day once again.27

Then all of a sudden the duckling flapped his wings. They beat more strongly than ever and swiftly carried him away. Almost before he knew it, he found himself in a large garden,28 where apple trees were in full blossom and fragrant lilacs bent their long green branches down on to the winding waterways. It was so lovely here, so full of the freshness of spring! Right in front of him, three beautiful white swans emerged from a nearby thicket, ruffling their feathers and floating lightly over the still waters. The duckling recognized the splendid creatures and was overcome by a strange feeling of melancholy.

“I want to fly over to those royal birds. Maybe they will peck me to death for daring to approach them, hideous as I am. But it doesn’t matter. Better to be killed by them than to be nipped by the ducks, pecked by the hens, kicked by the maid who tends the henhouse, and suffer hardship in the winter.”

The duckling landed on the water and swam out to the majestic swans. When they caught sight of him, they rushed to meet him with outstretched wings. “Oh please, just kill me,” cried the poor bird,29 and bowed his head down to the water, awaiting death. But what did he see reflected in the clear water? He saw his own image30 beneath him, but he was no longer a clumsy, dark gray bird, nasty and hideous—he was a swan!

HARRY CLARKE

“The new one is the most beautiful of all,” exclaim the children surrounding the pond. Clarke’s children are dressed in sophisticated, elegant attire that blends in with the landscape. The peacock in the foreground emphasizes the triumph of beauty in the tale’s conclusion.

There’s nothing wrong with being born in a duck yard, as long as you are hatched from a swan’s egg! He now felt positively glad to have endured so much hardship and adversity. It helped him appreciate all the happiness and beauty surrounding him. The great swans swam around him and stroked his neck with their beaks.

Some little children came into the garden and threw bread and grain onto the water. The youngest cried out: “There’s a new swan!”

The other children were delighted and shouted: “Yes, there’s a new swan!” And they clapped their hands and danced around and ran to fetch their fathers and mothers. Bits of bread and cake were thrown on the water, and everyone said: “The new one is the most beautiful of all. He is so young and handsome.” And the old swans bowed before him.

The duckling felt quite bashful and tucked his head under his wing—he himself hardly knew why. He was so very happy, but not at all proud, for a good heart is never proud!31 He thought about how he had been despised and scorned, and he heard everybody saying now that he was the most beautiful of all the beautiful birds. And the lilacs bowed their branches toward him, right down into the water. The sun shone so warm and so bright. Then he ruffled his feathers, raised his slender neck, and rejoiced from the depths of his heart. “I never dreamed of such happiness32 when I was an ugly duckling!”

MARGARET TARRANT

The swans approach the children, looking for bits of bread and cake. The redheaded girl points to the new arrival, who is also the youngest and handsomest in the quartet.

1. Ugly Duckling. Andersen conceived the story in 1842 while living at an estate named Bregentved, where he became absorbed in the beauty of the landscape. During a stay in Rome, he declared the “Book of Nature” to be his real tutor: “On my silent walks, close to the ancient manor houses, I discovered more than I could ever have derived from wisdom in books. Here, I could be independent, give myself over to and become part of Nature” (Travels, 230).

Andersen reports that he first contemplated the title “The Young Swans”: “While I was writing I was often undecided, Duck or Swan? I ended by calling it ‘The Ugly Duckling,’ since I did not want to betray the element of surprise in the duckling’s metamorphosis.” He also emphasizes the tale’s confessional nature: “This story is, of course, a reflection of my own life” (Travels, 232).

The term “ugly duckling” has become code for an unpromising person who ends up surprising and surpassing everyone else. In fairy tales, the despised prove their worth, the slow triumph over the swift, the stupid outsmart the clever. Jenny Lind, the “Swedish nightingale” with whom Andersen fell in love, was enraptured by “The Ugly Duckling,” and she lavished praise on the story in a letter of 1844 to Andersen: “Oh, what a marvelous gift to be able to put in words your most noble thoughts. To make us see, with a mere scrap of paper but with wit, how the most outstanding people are sometimes hidden and disguised by their wretchedness and rags until the hour of transformation strikes and reveals them in a divine light.”

2. it was summertime! For Andersen, summer was the season of hope, and he sets the scene with descriptions that capture his own sense of exhilaration at sights in the countryside. In the summer of 1842, he spent time at two Danish manors that seemed to him like “fairy caves,” and his diary records landscape descriptions that anticipate what appears in “The Ugly Duckling.” The pastoral scene of the beginning is set at a time when the natural beauty of the countryside is at its height.

The beautiful visual effects in this story are not at all anticipated by the term “ugly” in the title. This tale in particular led many of Andersen’s contemporaries to think of him as an illustrator as well as an author, and indeed he had an artist’s eye for beauty. Andersen enjoyed sketching at home and on his travels, and he left behind over three hundred drawings and well over one thousand paper cuts. He was also an enthusiastic visitor of museums and kept track of the many paintings he saw in his travel diaries.

3. chattering away in Egyptian. Legend has it that storks were once men and that they returned to their human state in Egypt during the winter. That storks bring babies is a familiar superstition, which seems to derive from the fact that the birds have long been perceived as harbingers of good fortune and happiness. It was believed that they picked up infants from marshes, ponds, and springs, where the souls of unborn children dwelled. Storks and birds in general (associated with freedom and hope) appear frequently in Andersen’s stories, and one of the tales he wrote is entitled “The Storks.”

Andersen reports that he was frequently inspired by the sight of birds—swallows and storks in particular. In 1848, he wrote: “Many of my stories are caused by a ‘sighting’ from outside. Anyone with the eye of a poet can look at life and nature and experience a similar revelation of beauty. It could be called ‘accidental poetry’ ” (Travels, 300).

4. an old castle. The grounds bear a striking resemblance to Bregentved, the old manor house, complete with moats and drawbridges, where Andersen began writing the story. (Andersen had already achieved a degree of fame that allowed him to take advantage of hospitality from admirers of his work.)

5. huge burdock leaves. The burdock plant is a coarse, broad-leaved weed bearing prickly heads of burr. It grows wild on waste ground, by roadsides, and in wet areas and has large lower leaves on thick stalks sometimes reaching a foot in height. Its unattractiveness contrasts with the natural beauty of the area in which it grows. The plant introduces the theme of gawky unsightliness, but beyond that it also serves as a womb-like (“secret”) shelter, one that connects love and birth, for the burdock’s lower leaves are heart-shaped at the bottom and egg-shaped at the top.

6. “The world is so big!” Andersen’s tales often draw a contrast between the rural and the urban or between the local delights of the village and the urban anarchy of towns and cities. (He himself had experienced both the small-town serenity of Odense and the alluring hustle and bustle of Copenhagen.) For the newborn ducklings, as for all children, the measure of the world is taken by how far the eye can see. The “wide world” is a recurrent theme in the stories, and vast expanses are seen as both intimidating and exhilarating.

7. looking ever so big and hideous. The hideousness of the “duckling” contrasts with the “loveliness” of the other newborns, whose attractiveness has a moral as well as aesthetic dimension. Andersen does not use the Danish equivalent of “ugly” until the end of the tale.

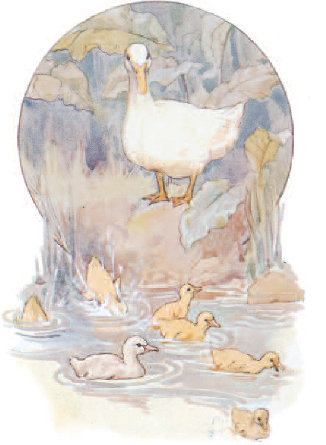

MARGARET TARRANT

The ducklings take their first plunge and have no trouble coming back to the surface. Perched on a stone, the mother duck takes note of the one anomaly in the group.

8. “She’s the most genteel of anyone here.” Note that Andersen’s farmyard has its hierarchies and social rankings, and that the psychological dynamics and social organization resemble that of the human world. Andersen himself suffered perpetually under the burden of his social origins, and some critics see in the farmyard a symbolic representation of Odense, Copenhagen, Slagelse, and Elsinore, places at which Andersen documented the resistance he felt to social acceptance.

W. HEATH ROBINSON

The duckling is picked on by everyone. Even the maid who feeds the poultry threatens him, and he tries desperately to escape. Far larger than the small duckling, the maid menaces the poor creature with her pot and with the dark shadow she casts.

9. “he’s a drake, and so it doesn’t matter as much.” In fairy tales, looks count less for the heroes than the heroines, who usually succeed in living happily ever after because of their perfect beauty. By contrast, even a beast can win a fair princess, although Andersen’s ugly duckling does not take up that particular opportunity.

10. pecked and jostled and was teased. As a boy growing up in Odense, Andersen kept to himself, but he witnessed the cruelty of schoolboy taunts when his mentally unstable grandfather was chased down the street. Attending school in Slagelse, he became—as the oldest and tallest in the class—the perpetual target of teasing.Even as an adult, Andersen found himself subject to constant insults. In his travel diaries, he recalls an incident that took place at the theater, when he intimated to an acquaintance that he might be attending a ball held by King Christian VIII. “What was your father?” the friend asked. “The blood rose to the top of my ears,” Andersen recalls. “ ‘My father was a shoemaker!’ I said. ‘I am what I am, with the help of God and my own initiative, and I would hope that was something you could respect.’ ” Andersen adds that he never received an apology “for this slight” (Travels, 229–30).

11. The ducks nipped at him. The cumulative effect of bites, nips, and kicks drives the duckling from the “civilized” world of the barnyard to the swamp, where wild creatures live. An outcast in the animal world, the duckling is scorned by humans as well—the girl who feeds the animals represents the lack of charity in humans as well as animals toward the unsightly appearance of the duckling. “It’s because I’m so ugly,” the duckling declares as he reproaches himself by pointing to the disruptive energy of ugliness and how it is seen to elicit hatred and aggression. As so often in Andersen’s writing, a series of events leading to a climactic turn is captured at a breathless pace: the ducks nip, the chickens peck, and the maid kicks until the poor animal flees.

12. until he reached some marshes. Andersen referred to himself as a swamp plant, a form of life that had originated in murky waters. Note also that the swamp is an in-between zone, one that combines solid land with watery depths.

13. He wasn’t dreaming about marriage. While many fairy-tale heroes rise in social station through marriage, the duckling aspires merely to social acceptance. For those who read the story in biographical terms, it is worth noting that Andersen remained a bachelor all his life.

14. wild geese. One critic has identified the wild geese as the young Bohemian poets with whom Andersen associated during his schooldays at Slagelse. Fritz Petit, who translated Andersen into German, and Carl Bagger, to whom the volume containing “The Ugly Duckling” is dedicated, lived loosely and encouraged Andersen—unsuccessfully—to indulge in a more reckless lifestyle. The swans that appear at the end of the story stand in stark contrast to the wild geese and have been seen as representing the great writers of Europe.

15. The water turned red with their blood. The soothing greens and yellows of the rustic landscape are turned red with blood and become blue with smoke from the guns. The appearance of hunters in the wilderness marks a second, even more violent, incursion by humans into settings populated by animals. Both domestic creatures and wild animals are threatened by the brutality of human agents.

16. An old woman was living in the cottage with her tomcat and hen. The duckling has an opportunity to escape the threats from the barnyard and the dangers of the wilderness and to try out the comforts of interiority and domestic life. The old woman plays a subordinate role in the household, with the purring cat and the egg-laying hen serving as master and mistress. Unable to adjust to the two domineering figures and longing for fresh air and sunshine (despite the perils of the “wide world”), the duckling returns to his natural element.

17. “But it’s so lovely to glide on the water.” The duckling, unlike the hen that can lay eggs, provides no added value in the household. Even as a swan, he will produce nothing but pleasure, gliding on the waters and diving into them to indulge himself and to evoke the admiration of observers.

18. “I should like to know who does.” The duckling remains misunderstood, despite repeated efforts to find a place where he feels at home. Like many characters in Andersen’s short stories, he is determined to seek a second home, a place where he can escape persecution.

19. a raven perched on a fence. Often considered birds of ill omen, ravens are also famous for their intelligence. The term “raven’s knowledge” means knowledge of all things. The croaking of the raven has a venerable literary tradition suggesting doom: “The raven himself is hoarse / that croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan / under my battlements,” Lady Macbeth declares (Macbeth I, 5). It is not by chance that common parlance refers to a “terror of ravens” or a “murder of crows.” As birds who feed on carrion, ravens have come to be associated with vengeance, death, and with the doom and gloom of Poe’s raven, who repeats the word “nevermore.”

20. had never seen anything so beautiful. The story begins in an idyllic country setting marked by sunshine and summer beauty. Scenes of squalor and degradation follow, but the appearance of the swans provides a burst of beauty in a season of clouds, cold, hail, and snow. The birds are not only physically beautiful, they also have “wondrous” calls that heighten the astonishment produced by their appearance. The aesthetic effect of the birds conveys the experience of the sublime, a moment in which shock mingles with wonder, leading the duckling to let loose a cry and plunge into the waters. The “whiteness” of the swans contrasts with what is described as the “black-gray” hues of the duckling.

21. He had no idea who those birds were. Andersen takes us inside the mind of the ugly duckling. Unlike conventional fairy tales, Andersen’s stories let us inhabit the minds of the central characters, feeling their pain and enjoying their pleasures. The introspective turn and perpetual selfanalysis of the characters leads to a constant monitoring of their affect. The prominence of phrases such as “he felt,” as in this passage, makes it clear how important it was to Andersen to have the reader establish an empathetic relationship to his characters.

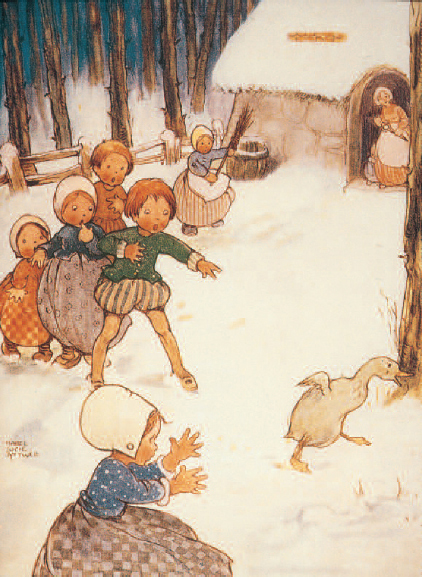

MABEL LUCIE ATTWELL

The ugly duckling’s gawkiness makes him a misfit. The children react to him with astonishment and trepidation, pointing fingers and keeping their distance but also moving forward with gestures and implements that threaten the duckling’s safety. The creature is clearly not in his element.

22. frozen fast in the ice. In the pond, the ugly duckling struggles to stay alive, and, in a classic triple sequence that is a trademark of Andersen’s style, he is “faint with exhaustion,” “quite still and helpless,” and finally, “frozen fast in the ice.” The final phrase points to the duckling’s glacial incarceration: he becomes a petrified ornament in the pond, dead to the world. For Andersen, a turn away from carnality (sometimes taking the extreme form of mortification of the flesh and physical paralysis) serves as the prerequisite for spiritual plenitude and salvation. This episode points up the cult of suffering embedded in Andersen’s stories—physical distress and spiritual anguish are a sign of virtue. It could, alternatively, be argued that the ugly duckling undergoes a test of his character and fortitude. Staunchly enduring taunts from others and defying the physical challenges of nature, he steadfastly paddles his legs to stay alive.

MARGARET TARRANT

The duckling flees after flying into the butter tub and overturning the flour bin. The duckling is already in a transitional stage, halfway to becoming a swan.

23. took the duckling home to his wife. In this final, failed attempt to find refuge, the ugly duckling’s disruptive presence becomes evident. His “ugliness” and clumsiness become stimuli for aggression, with a farmer’s wife who repeats the violence of the girl who feeds the animals in the barnyard.

24. the duckling was afraid they would hurt him. Andersen’s surprising dislike of small children, given the audience for his stories today, is well documented. In the plan for a commemorative statue in Copenhagen, he asked that the child looking over his shoulder be removed from the design. But his hatred of one of the sketches, which reminded him of “old Socrates and young Alcibiades,” may have been inspired by very different anxieties. As a child he was an avid reader, who stayed away from other children. “I never played with the other boys,” he reported in a letter to his benefactor Jonas Collin, “I was always alone.”

25. fluttering right into the milk bowl. One commentator notes that the duckling flies “into the milk (the substance of creation), butter (a source of richness and abundance), and flour (a distillation of earth energy).” Those elements are reconstituted and baked in the bread tossed by the children at the swans (Gambos, 70).

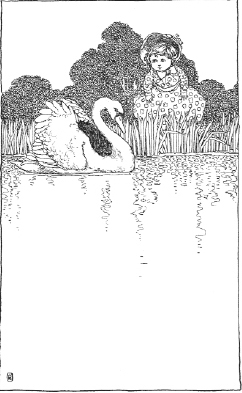

W. HEATH ROBINSON

The swan glides on the surface of the water while a girl gazes at him from the marshes with admiration.

26. It would be dreary. The narrator claims to suppress the desire to elaborate on the misery endured by the duckling, and yet the story of the ugly duckling provides painful details about all the hardships, physical and mental, suffered by the tormented animal.

27. it was a beautiful spring day once again. The return of spring signals the renewal of hope. For Andersen, every season has a different affective power, with all of the obvious cyclical associations of winter with death and spring with rebirth and renewal. Summer and spring are, as in “The Snow Queen,” always a time of joy.

28. he found himself in a large garden. The garden represents the point at which nature and culture meet, the place where the ugly duckling finds happiness at last. The utopian beauty of the garden, with its colors and fragrances, becomes the perfect setting to display the beauty of the swans.

29. “Oh please just kill me,” cried the poor bird. The duckling’s suffering is so intense that it moves him toward selfannihilation. It is startling that he looks on death as salvation, so long as the beautiful swans are the executioners.

30. He saw his own image. In this scene of transformation, the ugly duckling engages in a moment of reflection—reflection in the double sense of the term. He sees himself mirrored in the surface of the water and also analyzes his condition. In this extraordinary humanizing moment—animals cannot engage in this double process—the ugly duckling transcends both ugliness and his animal condition. Self-reflexivity may not be the cause of the transformation, but it is telling that it coincides with the transformation.

If the ugly duckling triumphs in the end and reigns supreme as the “most beautiful of all,” he is also reduced to the rank of an ornament, gliding on the surface of the pond as he is admired by children who reward his preening with bits of bread. Many scholars have argued that “The Ugly Duckling” is the most deeply personal of Andersen’s stories, a narrative that traces his trajectory from humble origins to a literary aristocracy with a deeply servile attitude in relation to the real aristocracy. Jack Zipes comments that it only “appears as though the swan has finally come into his own. . . . As usual, there is a hidden reference of power. The swan measures himself by the values and aesthetics set by the ‘royal’ swans and by the proper well-behaved children and people in the beautiful garden. The swans and beautiful garden are placed in opposition to the ducks and hen yard. In appealing to the ‘noble’ sentiments of a refined audience and his readers, Andersen reflected a distinct class bias if not classical racist tendencies” (Zipes 2005, 70).

Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith’s “The Really Ugly Duckling” provides a postmodern revision of Andersen’s tale, one in which there is no transformation, just the move from being an ugly duckling to a “really ugly duck.” As Jean Webb points out, “The convention of transformation so essential to the tradition of the fairy tale has been supplanted by the removal of the sublime experience, the achievement of the ideal. The postmodern perspective recognizes that we cannot become ideal selves, idealized forms, for there are realities which have to be accepted” (Webb, 161).

31. a good heart is never proud! For Andersen, pride and vanity are the cardinal sins of humanity, and, despite the fact (or perhaps because of the fact) that he was guilty of both, he never ceased to excoriate both. Those with a humble heart are the true heroes of mankind, and they are often oppressed by the haughty, arrogant, and proud. Children from prosperous families scorned the young Andersen and mocked him with the words “Look, there’s the playwright!” In his memoirs, Andersen recalls that he went home, hid in a corner, and “cried and prayed to God.” Later in life, he suffered countless insults from his patron Jonas Collin and his family members, who always made him aware that he was their social inferior. Danish reviewers of Andersen’s work were also less kind than critical and condescending, constantly pointing to the author’s class origins and aspirations to a higher social rank. “When I was young,” Andersen pointed out, “I could cry; now I can’t! I can only be proud, hate, despise, give my soul to the evil powers to find a moment’s comfort.” As he reflected further on the vitriolic reviews of Danish critics, he warmed to his topic: “The Danes are evil, cold, satanic—a people well suited to the wet, moldy-green islands from where Tycho Brahe was exiled. . . . May I never see that place; may never a nature such as mine be born there again. I hate, I despise my home, as it hates and spits upon me!” (Diaries, 137–38)

32. “I never dreamed of such happiness.” In a famous essay of 1869 on Andersen, the renowned Danish literary critic George Brandes denounced the servile tone of “The Ugly Duckling” and its glorification of a tamed existence: “Let [the duckling] die if necessary, that is tragic and grand. Let it lift its wings and fly soaring through the air, jubilant at its own beauty and strength” (Bredsdorff 1993, 154). The fantasy of such sublime happiness was fulfilled in part for Andersen after the astonishing success of the fairy tales in Denmark and abroad. “The Ugly Duckling” was one of the tales that transformed him from a local writer into a celebrity of international importance.