Fyrtøjet

Eventyr, fortalte for Børn. Første Samling. 1835

Andersen’s early fairy tales draw on oral storytelling traditions that revel in cruelty, violence, earthiness, and vulgarity and move in a burlesque mode very different from the pious tone of tales like “The Little Match Girl.” In part because of its preposterous excesses (the soldier in “The Tinderbox” is guilty of everything from ingratitude and homicide to theft and regicide) but also its exquisitely charming moments (the three dogs filled with wonder at the wedding), the story has retained a certain appeal that allows it to stay alive despite its many violent turns.

“The Tinderbox” was the opening tale of Andersen’s Eventyr, the first installment of his fairy tales. It is based on a Danish folktale known as “The Spirit of the Candle” and has multiple allusions to other fairy tales—“Rapunzel” (the princess in the tower), “Hansel and Gretel” (the trail of grain), and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” (the marking of doors). In his early stories for children, Andersen borrowed bits and pieces of tales from the oral storytelling traditions of various cultures, cobbling them together to form a complete narrative. It was only after the publication of “The Little Mermaid” in 1837 that he relied fully on his own powers of imagination to construct fairy tales.

The soldier-hero of “The Tinderbox” shares many traits with war veterans found in stories by the Grimms and other European collectors. Brutal, greedy, and impetuous, he is not much of a role model for children listening to the story. Indeed, stories about soldiers returning from war were generally intended for adult audiences rather than for children, although Andersen adds enough magic and whimsy to make the tale attractive for young and old.

A soldier came marching down the road2—left, right! left, right! He had a knapsack on his back and a sword at his side, for he had fought in the war. But now he was returning home. On the road he met an old witch who was really hideous. Her lower lip dangled all the way down to her chest.

“Good evening, soldier,” she said. “What a fine sword you have there and what a big knapsack. You’re every inch a soldier! And now you shall have money too, as much as you could ever want!”

“Thanks very much, you old witch,” the soldier replied.

“Do you see that tall tree over there,” the witch said, pointing to a tree right near them. “It’s completely hollow inside. Climb up to the top, and you’ll find a hole that you can use to slip inside and then slide all the way down. I’ll tie a rope around your waist, and, as soon as you call out to me, I’ll hoist you back up again.”

“Why would I ever go inside that tree?” the soldier asked.

“For the money!” the witch replied. “Listen to my words. When you touch bottom, you’ll find yourself in a huge hall. It will be very bright in there because more than a hundred lamps are burning down there.4 You’ll see three doors, and you can open them up because there will be a key in each lock. If you open the first door, you’ll find a large chest right in the middle of a room. A dog will be sitting on top of it. His eyes will be as big as teacups, but don’t mind him at all. I’ll give you a blue-checked apron, which you can spread out on the floor. Go right over, pick up the dog, and put him on the apron. Then open up the chest and take out as many coins as you like. They’re all made of copper, but if silver suits you better, then go into the next room. You’ll find a dog in there with eyes as big as mill wheels. But don’t mind him. Just put him on the apron and take the coins. Maybe you prefer gold? Well, you can have that too. If you go into the third room, you can remove as much gold as you can carry. But there will be a dog sitting on the chest filled with money, and he has eyes the size of the Round Towers.5 Now there’s a real dog! But don’t mind him either. Just put him on my apron, and he’ll do you no harm. You can help yourself to as much gold as you want from the chest.”

“Not bad,” said the soldier. “But what’s in it for you, you old witch? I’m sure you want to have a share of it too.”

“No,” said the witch. “I don’t want a penny of it. All you have to do is bring me an old tinderbox that my grandmother left behind the last time she was down there.”

“Fine with me,” the soldier said. “Let’s put that rope around my waist.”

“There you go,” the witch said. “And here’s my blue-checked apron.”

The soldier climbed up the tree and slid right down to the bottom until he reached—just as the witch said he would—a huge hall where hundreds of lamps were burning.

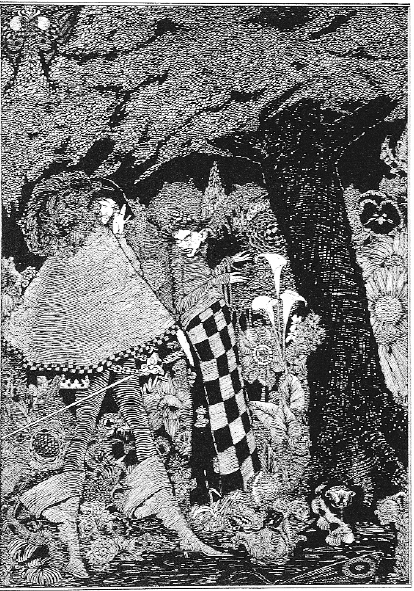

HARRY CLARKE

The dog with eyes as big as teacups guards the chest of copper coins while the soldier, in garments that are impressively variegated, contemplates the hall, with its many bright lights.

He opened the first door he saw. Yowee! The dog with eyes as big as teacups was sitting right there, glaring at him.6

“You’re a handsome fellow,” the soldier said, and he took him and set him right down on the witch’s apron. Then he took as many copper coins as his pockets would hold.7 He closed up the chest, put the dog back on it, and went into the second room. Yikes! There was the dog with eyes as big as mill wheels.

“Don’t stare at me like that,” the soldier said. “You might strain your eyes.” And he set the dog down on the witch’s apron. When he saw all the silver coins in the chest, he threw away the copper coins and filled his pockets and knapsack with the silver ones. Then he entered the third room. What a horrible sight to see! The dog in there really did have eyes as big as the Round Tower, and they were spinning around in his head like wheels.

“Good evening,” the soldier said, and he saluted, for he had never seen a dog like that in all his life. But after he had stared at him for a while, he thought, well, enough of that! And he lifted the dog up, set him down on the floor, and threw open the chest. Good Lord! What a heap of gold! Enough to buy all of Copenhagen, along with every single sugar pig8 sold by the cake-wives, and all the tin soldiers, whips, and rocking horses in the world! Yes, that was a lot of money!

The soldier got rid of all the silver coins in his pockets and in his knapsack, and he put the gold ones in their place. Yes, sir, he packed his pockets, his knapsack, his cap, and his boots so full that he could hardly walk! Now he was made of money! He set the dog back down on the chest, slammed the door shut, and hollered up through the hollow tree: “Hoist me up now, you old witch!”

“Did you remember the tinderbox?” the witch asked.

“Confound the tinderbox,” the soldier shouted back. “I forgot all about it.”

He fetched the box, and the witch pulled him up. There he was, back on the road, with pockets, boots, knapsack, and cap full of gold.

“What do you want with that tinderbox?” the soldier asked the old witch.

“None of your business,” the witch replied. “You have your money now, so just hand it over.”

“Stuff and nonsense,” said the soldier. “Tell me on the spot why you want it, or I’ll take out my sword and chop your head off!”9

“I won’t,” the witch shouted.

And so the soldier chopped off her head. There she lay! He took her apron, wrapped all his money up in it, slung it in a bundle over his shoulder, put the tinderbox in his pocket, and headed straight for the city.

It was a splendid city. All that money had turned him into a rich man, and so he took the best rooms at the finest inn and ordered his favorite dishes.

The servant at the inn who was supposed to polish his boots found them to be an oddly shabby pair of boots for a man of such means. The soldier had not yet had the time to buy a new pair, but by the next day he had a good pair of boots and some fine new clothes. He had turned into a distinguished gentleman, and everyone was eager to tell him about all the attractions of the city, and about the king and his charming daughter, the princess.

“How do I get a look at her?” the soldier asked.

“It’s not so easy to catch a glimpse of her,” they all told him. “She lives in an enormous copper palace surrounded by many walls and towers. The king is the only one allowed to visit her, for there was once a prophecy that she would marry a common soldier, and the king was not at all happy about that.”

“I’d like to see her all the same,” the soldier thought. But how in the world could he ever make that happen?

The soldier was having a splendid time, going to the theater and taking carriage rides in the king’s gardens. He also gave a lot of money to the poor, which was to his credit, for he remembered how miserable it was not to have a penny in your pocket. Now that he was wealthy and well dressed, he had many friends who called him a fine fellow and a true gentleman. That made him feel good, but because he was spending money every day without taking anything in at all, he ended up with nothing but two pennies to his name. He had to leave the comfortable rooms in which he was living and move into a garret, where he polished his own boots and repaired them with a darning needle. None of his old friends came to see him because there were far too many stairs to climb.

One evening, while he was sitting in the dark because he could not afford even a candle, he suddenly remembered that there was the stump of one in the tinderbox that he had taken from the hollow tree which the witch had helped him climb into. He took out the tinderbox and the candle stump, and, as soon as sparks flew from the flint, the door burst open and there stood the dog he had seen before—the one with eyes as big as teacups.

“What does my master command?” the dog asked.

“What on earth!” the soldier wondered. “Is this the kind of fabulous tinderbox that will get me whatever I want?” And he gave the dog an order: “Go get me some money.” The dog was gone in a flash, and in a flash he was back again, with a bag full of copper coins in his mouth.

The soldier now knew what a wonderful tinderbox he had in his possession. If you struck it once, the dog from the room with the chest of copper coins appeared. If you struck it twice, the dog with the silver coins appeared. And if you struck it three times, the dog guarding the gold coins appeared. The soldier moved back to his comfortable quarters, and he was soon wearing fashionable clothes again. It was not long before his friends began to recognize him, for they were all so fond of him.10

One day the soldier thought to himself: “How odd that no one is allowed to see the princess. Everyone says that she is very beautiful,11 but what is the point if she’s kept in that enormous copper castle with all those towers? Why can’t I have a look at her? Now where’s my tinderbox?” And then he struck fire and presto! there was the dog with eyes as big as teacups.

“I know it’s the middle of the night,” the soldier said. “But I would really like to see the princess, even if it’s just for a moment.”

The dog was out the door in a flash, and before the soldier knew it, he had returned with the princess. She was draped over the dog’s back, fast asleep, and she was so beautiful that anyone could tell she was a real princess.12 The soldier could not stop himself from kissing her—he was every inch a soldier.

The dog took the princess back home. The next day, when the king and queen were serving tea, the princess remembered a strange dream she had had that night about a dog and a soldier. She had been riding on the dog’s back, and the soldier had given her a kiss.

“That’s quite a story!” the queen said.

The next night one of the older ladies-in-waiting was ordered to keep watch at the princess’s bedside, to find out whether she had been dreaming or if it was something else altogether.

The soldier was longing to see the beautiful princess again. That night the dog appeared and took her away again, and he ran off as fast as he could. But the lady-in-waiting pulled on her storm boots and ran right after them. When she saw them disappear into a large house, she thought to herself: “Now I know where it is.” And with a piece of chalk she drew a big cross on the door. Then she returned home and went to bed, and the dog came back as well, bringing the princess with him. When the dog saw the cross marked on the door of where the soldier lived, he took his own piece of chalk and marked every door in the city.13 That was a clever thing to do, because now the old lady could not tell the right door from all the wrong doors he had marked.

KAY NIELSEN

The dog with eyes as big as teacups carries the sleeping princess on his back. She seems quite comfortable on a beast whose stylized curls contrast sharply with the spare architecture in the background.

The next morning, the king and queen, along with the lady-in-waiting and all the officers, wanted to find out where the princess had been.

“Here’s the place,” the king said when he saw the first door with a cross mark on it.

“No, it’s over here, my dear,” said the queen, who was looking at another door.

“But here’s one, and there’s another!” they all shouted. Everywhere they looked, they saw chalk marks. They quickly realized that it made no sense to continue searching.

The queen was an uncommonly wise woman who could do much more than ride around in a coach. She took a pair of big golden scissors,14 cut a large piece of silk into pieces, and then stitched together a pretty little pouch, which she filled with finely ground buckwheat. She fastened the pouch to the princess’s back and then cut a tiny little hole in it15 so that grains of buckwheat would fall wherever the princess went.

That night the dog returned, put the princess on his back, and ran off to the soldier, who loved her so dearly. The soldier just wished that he were a prince so that he could make her his wife.

The dog never noticed how the grains of buckwheat were dropping to the ground all the way from the castle right up to the wall he ran along to reach the soldier’s window. The next morning the king and queen knew exactly where their daughter had been, and they seized the soldier and threw him in prison.

There he sat. It was utterly dark and dismal, and they told him: “Tomorrow you are going to be hanged.” That did not cheer him up a bit, and, as for the tinderbox, he had left it behind at the inn.

In the morning he looked through the iron bars of his little window and could see people rushing to the outskirts of the city where he would be hanged.16 He heard the drums and saw the soldiers march by. Everyone was in a great rush, among them a shoemaker’s apprentice wearing a leather apron and slippers. He was moving at such a fast clip that one of his shoes flew off and struck the wall, right where the soldier had his face pressed to the iron bars.

“Hey there, shoemaker’s boy! What’s the rush?” the soldier shouted. “Nothing’s going to happen until I show up. I’ll give you four pennies if you run over to my place and bring me my tinderbox. But you’ll have to be quick about it.”

The shoemaker’s apprentice was more than happy to earn those four pennies, and he ran off to fetch the tinderbox, brought it to the soldier, and, now, let’s hear what happened!17

At the outskirts of the city a tall gallows had been erected, and soldiers were gathered around it, along with many hundreds of thousands of people. The king and queen were seated on a splendid throne, right opposite the judge and the entire council.

The soldier was already standing on the ladder, and they were about to put the rope around his neck when he pointed out that a sinner facing his punishment was always granted one last harmless request. He dearly wanted to smoke a pipe, and it was the last pipe that he would be able to have in this world.

How could the king refuse him? And so the soldier took out his tinderbox and struck fire from it—one, two, three, and presto! There stood all three dogs: the one with eyes as big as teacups, the one with eyes like mill wheels, and the one with eyes as big as the Round Tower.

“Help me now! Save me from hanging!” the soldier shouted. The dogs rushed at the judge and at the entire council, grabbing one person by the leg, another by the nose, and tossing them all so high up in the air that when they fell back down they broke into pieces.

“No, not me!” the king shouted, but the biggest dog seized him and the queen too, and tossed them up after the others. The soldiers trembled, and everyone shouted: “Little soldier, you must be our king and marry the beautiful princess!”

They carried the soldier into the royal coach. All three dogs danced in front of it, shouting “Hurrah!” while boys whistled through their fingers and soldiers presented arms. The princess emerged from the copper castle and became queen, and that suited her just fine! The wedding celebration lasted for a week, and the three dogs sat at the table, their eyes wide with wonder. 18

KAY NIELSEN

The three dogs, their eyes wide with wonder, celebrate the wedding of the soldier and princess.

1. Tinderbox. The Danish term fyrtøjet means, literally, “fire steel.” Andersen may have been inspired by a tale from the Brothers Grimm called “The Blue Light,” in which a wounded soldier is dismissed without pay from army service by an ungrateful monarch. The soldier comes into the possession of a blue light with the same magical powers as the tinderbox. But his rendezvous with a princess and revenge on the king are elaborated in slightly different fashion, with the princess forced into servitude and the king pardoned for his offenses. Gregory Frost has produced a new version of the story called “Sparks” in an anthology entitled Black Swan, White Raven.

HARRY CLARKE

In a lush landscape filled with massive flowers, the soldier meets the witch and is perplexed that she would want him to climb into a hollow tree.

2. A soldier came marching down the road. “The Tinderbox” has been described as Andersen’s version of “Aladdin,” the story of a young man destined to succeed no matter how he behaves. Stith Thompson reviews the main features of the plot known to folklorists as “Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp”: the finding of the lamp in an underground chamber, the magic effects of rubbing it, the acquisition of a kingdom and a wife, the theft of the lamp and consequent loss of fortune, and the restoration of the lamp by means of another magic object. In Andersen’s tale, the tinderbox is not lost through deception but is left at home by accident. Critics have seen in “The Tinderbox” a domesticated version of the Oriental tale (Oxfeldt, 53).

Andersen thought of himself as an Aladdin figure and, near the end of his life, he addressed the town of Odense, which had gathered to honor him, as follows: “I cannot help thinking about Aladdin, who with the help of his magic lamp was able to create a magic castle.” Andersen added: “Then I looked out of the window, and said: ‘I was once a poor boy down there, but thanks to God I was also granted a magic lamp, Poetry, and when my lamp shines out over the world, giving pleasure to people, and when they recognize that it comes from Denmark, then my heart feels ready to burst’ ” (Travels, 380).

3. her lower lip dangled all the way down to her chest. The witch’s deformity is shared by a crone in a fairy-tale trio of old women whose physical defects serve as a powerful warning against spending too much time spinning. In the Grimms’ tale “The Three Spinners,” one of the women displays a foot deformed from excessive treading, a second sports a lower lip hideously enlarged from licking thread, and a third exhibits a thumb broadened out of shape from twisting thread. Witches, hags, and crones appear with some frequency in Andersen’s tales, most notably in “The Little Mermaid” and “The Snow Queen.”

4. more than a hundred lamps are burning down there. The radiant hall suggests that the underground realm is associated with celestial rather than sinister powers. The soldier, of course, has to climb up the tree before he slides down through it.

In Kafka: Gothic and Fairytale, Patrick Bridgwater points out that Kafka’s “Parable of the Doorkeeper” was inspired in part by Andersen’s “Tinderbox”: “In the parable, the doorkeepers, each more formidable than the one before, are clearly based on the dogs guarding successive rooms in ‘The Tinder-Box,’ and the gleam of what might or might not be ‘eternal radiance [light]’ . . . visible through the doorway to the Law, will have been suggested, in part, by the light from the three hundred lamps in the great hall of Andersen’s story” (Bridgwater, 125). Although a link between the two writers seems somewhat improbable, Kafka’s tales have often been framed as modernist anti–fairy tales, driven by the same existential anxieties found in Andersen, but without the overlay of Christian sentiments.

5. Round Tower. The Round Tower, located in Copenhagen, was commissioned by King Christian IV as an observatory and completed in 1642. A winding passage over 200 meters in length leads to a platform from which there is a magnificent view of the city.

6. The dog with eyes as big as teacups was sitting right there, glaring at him. The terrifying creature guarding the chamber is kin to Cerberus, the multiheaded dog of Greek mythology who guards the entrance to Hades. With the tail of a dragon and a neck bristling with snakes, Cerberus is even more frightening than the third in the trio of dogs guarding the underground chambers. The giant Argus of Greek mythology, with his one hundred eyes (only two of which sleep at a time), is another watchman characterized by unusual ocular traits.

7. as many copper coins as his pockets would hold. Copper, silver, and gold are known as the coinage metals, and, because they resist corrosion and do not react with other elements, they were at one time commonly used to make coins the world over. As the soldier’s journey progresses, the metals become progressively more precious, leading the soldier to discard the coins he had taken from the previous room. In some fairy tales, as in “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” the sequence of metals starts with silver and gold and ends in diamonds. In The Merchant of Venice, Portia is famously bound to wed the man who can pick the right one of three caskets, one made of gold, another of silver, and a third of lead. Bassanio triumphs when he makes the modest choice and expresses a preference for the casket of lead.

8. every single sugar pig. Cakes and candy made in the shape of a pig were popular desserts in Denmark, and they make an appearance in “Ole Shut-Eye” (1850) as well. Andersen was an expert in capturing children’s fantasies about what money could buy, and the sugar pigs, tin soldiers, and rocking horses are much like the toys enumerated in “The Steadfast Tin Soldier” or “the whole world and a pair of new skates” in “The Snow Queen.”

9. “chop your head off!” With his knapsack and sword, the soldier can be seen to embody ruthless greed and violence—filling his knapsack with as much gold as possible and killing with his sword anyone who crosses him. Decapitation was a common punishment in European fairy tales, and Andersen’s tales include both this scene of decapitation and one of amputation (Karen’s feet are chopped off in “The Red Shoes”). Jack Zipes sees in the soldier’s acts of violence a reflection of “Andersen’s hatred for his own class (his mother) and the Danish nobility (king and queen),” which is “played out bluntly when the soldier kills the witch and has the king and queen eliminated by the dogs” (Zipes 1999, 94). He also sees in the tale a “formula” that leads to economic success: “Use talents to acquire money and perhaps a wife, establish a system of continual recapitalization (tinderbox and three dogs) to guarantee income and power, and employ money and power to maintain social and political hegemony” (Zipes 2005, 35).

10. for they were all so fond of him. Although the soldier inhabits a fairy-tale world in which the social actors are limited to those who help or harm the hero, Andersen persistently embedded biting satirical remarks into the plot. The friends seem to have no other function in the tale but to serve as reminders of shameless hypocrisy. These are the same friends who will find themselves unable to climb a flight of stairs to visit the penniless soldier.

11. Everyone says that she is very beautiful. The legendary beauty of the princess becomes intensified by the fact that she is kept in a mausoleum-type domicile. The copper castle resembles the tower Rapunzel inhabits—both are structures designed to wall in the heroines and keep them out of sight. The soldier’s appreciation of beauty, his desire to set eyes on the princess because of her storied beauty, makes him a true hero in Andersen’s fairytale pantheon.

12. anyone could tell she was a real princess. The beauty of this princess makes superfluous a test such as the one in “The Princess and the Pea.” Like the prince in “Snow White” and in “Sleeping Beauty,” the soldier cannot stop himself from planting a kiss on the lips of the slumbering princess.

13. marked every door in the city. The dog knows his fairy tales, for the marking of other doors to detract attention from the right door is a form of trickery used to outwit robbers in “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.”

14. She took a pair of big golden scissors. In the Hans Christian Andersen Museum in Odense can be found the large scissors that Andersen used to make nearly 1,500 paper cuttings on social occasions and while he was telling stories. Kjeld Heltoft’s Hans Christian Andersen as an Artist has a photograph of those scissors and reproduces many of the intricate paper cuttings. Heltoft quotes Baroness Bodild Donner’s description of Andersen at work: “When I was a child, I looked forward to his cutting out little dolls in white paper, all joined together, which I could place on the table and blow at so that they moved forward. . . . He always cut with an enormous pair of scissors—and I simply couldn’t understand how, with his big hands and enormous scissors, he could make such pretty, dainty things” (Heltoft, 207).

15. cut a tiny little hole in it. The strategy is familiar from tales like “Hansel and Gretel” and “The Robber Bridegroom,” in which breadcrumbs and ashes mark a path. In Andersen’s story, the plan works, but, in the Grimms’ “Hansel and Gretel,” birds eat the breadcrumbs, obliterating the trail that was to help the two children find their way back home.

16. rushing to the outskirts of the city where he would be hanged. As a schoolboy, Andersen was given the day off to travel to the outskirts of Skælskør, where the wife of a farmer, his daughter, and a manservant were hanged for conspiring to murder the farmer. The event left a deep impression on the young Andersen, who later wrote about it in his autobiography: “I shall never forget seeing the criminals driven to the place of execution: the young girl, deadly pale, leaning her head on the chest of her strapping sweetheart; behind them the manservant, livid, his black hair disheveled, and nodding with a squint at a few acquaintances, who shouted ‘Farewell’ to him. Standing by their coffins, they sang a hymn together with the minister; you could hear the girl’s voice above all the others. My legs could scarcely hold me up. These moments were more horrifying to me than the moment of death” (The Fairy Tale of My Life, 52). Note that the story begins with a decapitation and nearly ends with an execution.

Capital punishment was entirely eliminated as a possibility in Denmark in 1994. The last public execution was carried out in 1882, and 1892 marked the last year in which capital punishment was carried out in Denmark.

17. now, let’s hear what happened! Mimicking the style of the folk raconteur surrounded by listeners, Andersen seems to take his cue from the soldier’s query (“What’s the rush?”) and slows down the narrative pace by inserting a question of his own.

18. their eyes wide with wonder. The dogs, who themselves aroused wonder with their eyes as large as teacups, mill wheels, and the Round Tower, now gaze with astonishment at the wedding celebration for the soldier and his beautiful princess-bride. Ending the story with the image of wideeyed wonder points to Andersen’s deep commitment to providing the old-time enchantments of oral storytellers. In many ways, Andersen’s efforts to arouse wonder also anticipate Lewis Carroll’s use of stories to capture the attention and imagination of children by arousing their sense of wonder. Recall the ending of Alice in Wonderland, with Alice’s sister imagining that she might be able to “gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale.”