27

Killing bin Laden

Abbottabad, Pakistan, 2 May 2011

The night was moonless, and the two Ghost Hawk helicopters painted the exact shade of the Pakistani darkness followed the rugged contours of the Pir Panjal mountains, skimming close to avoid radar detection, then abruptly banking right and low towards the town of Abbottabad. On board the first sat a dozen US Navy Seals, crammed together and tense, their superfit bodies bristling with grenades and ammunition, night-vision goggles pulled over their eyes. In the second were eleven Seals and a Pakistani-American CIA interpreter as well as a specially trained tracking dog named Cairo, a Belgian Malinois kitted out in dog body-armour and goggles.

At fifty-six minutes after midnight the words ‘Palm Beach’ came over the radio, signalling three minutes to landing. Their destination was a three-storey house inside a high white-walled compound which looked just as it did in the photographs they had seen and at the purpose-built mock-up thousands of miles away in a forest in North Carolina, where for the past few weeks they had practised their mission. The commandos gripped their rifles, M4s or MP7s, released a round into the chamber with a metallic click and muttered some final prayers, ready to fast-rope down onto the roof of the building.

Airborne night raids were part of life for these men, but they had never carried out one quite like this. Some took a last look at the leaflets folded in their pockets, on which were printed a series of names, photographs and descriptions of the men and women living in the compound. The gaunt, bearded face on the top – ‘age 54, height 6’4 to 6’6, weight 160lbs, eyes brown’ – needed no introduction. His codename at US Special Operations Command was ‘Crankshaft’, but the Seals referred to him as ‘Bert’, after the tall, thin Muppet in Sesame Street (they referred to his portly deputy Ayman al Zawahiri as ‘Ernie’). The world knew him as Osama bin Laden, the most wanted man on earth.

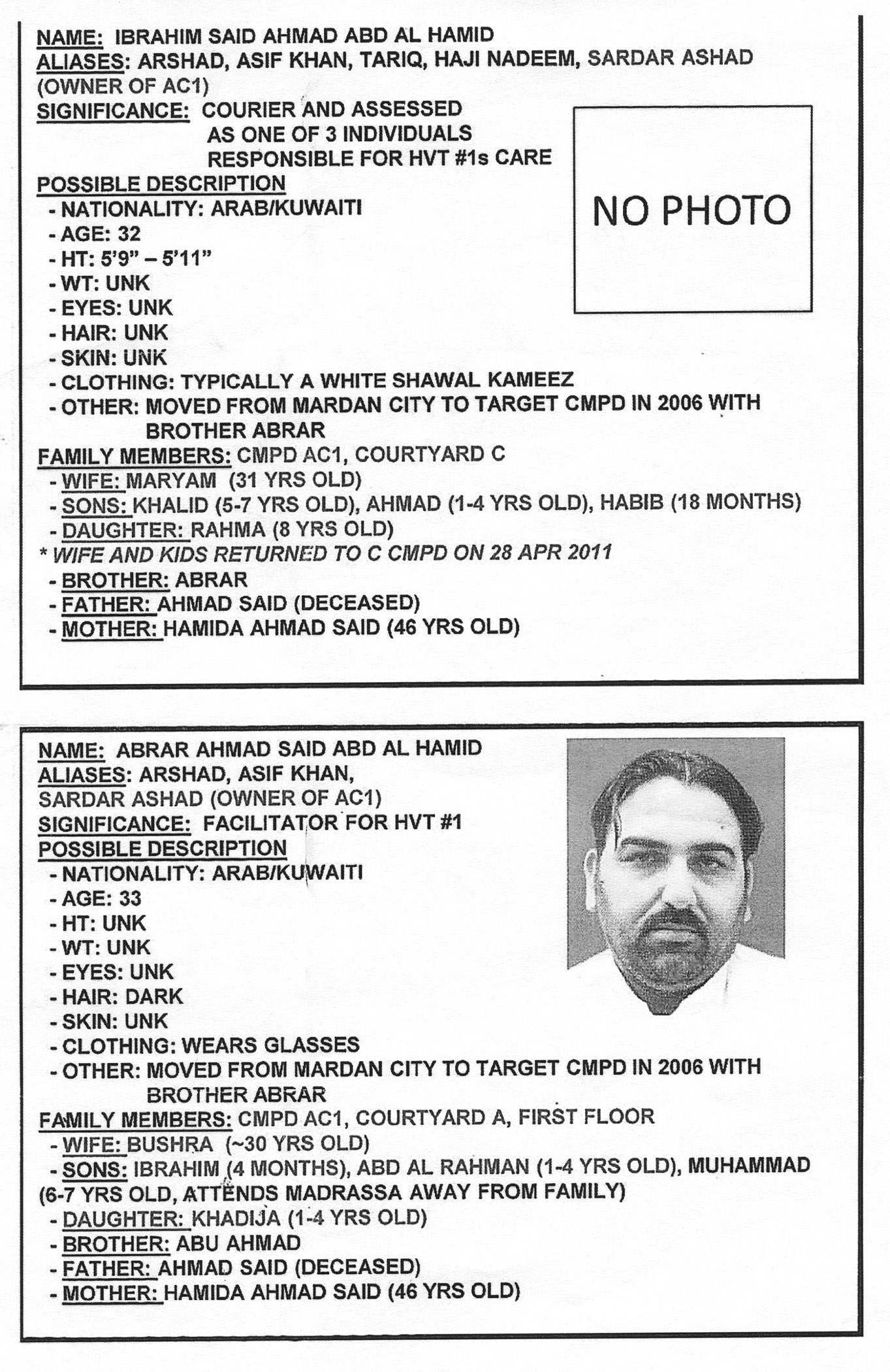

Also on the leaflet were three of bin Laden’s four wives, seven of his children, two grandchildren and two other men – Ibrahim Said Ahmad Abd al Hamid, known as al Kuwaiti, or ‘the Kuwaiti’ (he had been born in Pakistan to a Kuwaiti father), and described as a ‘courier’, his wife and four children, and his brother Abrar with his wife and four children. There were however lots of blank spaces and question marks. Though the house had been watched for months, no one knew exactly what or who they would find inside.

Overhead a Sentinel drone circled 20,000 feet up, sending back live video to officials at CIA headquarters in Virginia and the Situation Room of the White House, to which President Obama had just returned from nine holes of golf at Andrews Air Base, his usual Sunday programme. Among those gathered with him were Admiral Mike Mullen and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, as well as Vice President Joe Biden and Defense Secretary Bob Gates, both of whom had been sceptical about the operation.

Five minutes behind the strange, humpbacked Ghost Hawks came four more helicopters, Chinooks carrying a quick-reaction force in case anything went wrong. The first was the Command Bird, which bore the commanding officer of Seal Team Six, the elite unit carrying out the raid. The second was the Gun Platform, equipped with three M134 Gatling guns. This would spend the raid hovering three hundred feet above the compound, ready to engage any armoured vehicles or troops that attempted to interfere with the operation, or anyone who tried to flee. A third and fourth helicopter landed in a valley some distance away.

The Ghost Hawks were Black Hawks modified with a skin that meant they barely showed up on radar and made little more sound than a whisper. It was the noise of the Chinooks that woke Aslam Khan, a businessman who lived in the house next door. ‘At first I thought it was a tractor ploughing a field,’ he said. He looked at his watch and saw it was 1 a.m. ‘Then my son told me it was a helicopter.’ They ran to the window, but the electricity had gone off. In the darkness and dust thrown up by the rotors they could see nothing. Khan’s confusion turned to terror when moments later a blast from his neighbours’ courtyard shattered his windows. The explosion, along with the sound of ‘seven or eight’ gunshots, told him this was not some routine exercise from the nearby military training school, and he started to panic. ‘My daughter was very afraid and I took my family and we ran out of the house.’

He was not the only one to be woken. A mile and a half away, near Jalal Baba Park, an IT consultant called Sohaib Athar was jolted awake by the whirr of helicopters. He instantly reached for his phone and tweeted, ‘Helicopter hovering above Abbottabad at 1 a.m. (a rare event).’ The thirty-three-year-old had recently moved from Lahore, fed up with its frequent bombings, to what he thought was a safe, sleepy town, so he was not best pleased. ‘Go away helicopter – before I take out my giant swatter,’ he added, followed by, ‘A huge window-shaking bang here in Abbottabad Cantt [cantonment]. I hope it’s not the start of something nasty.’ For the next half-hour Athar continued to post about everything he heard on Twitter, without the faintest clue that his musings were the world’s first public record of Osama bin Laden’s final moments. The realisation hit him only when he got up on Monday morning and switched on the TV. ‘Uh-oh, now I’m the guy who live-blogged the Osama raid without knowing it,’ he typed.

The bang he had heard had been the Seals blasting their way into the compound. That had not been part of the plan, but the first Stealth helicopter, codenamed ‘Razor 1’, had been caught in a downdraught in warmer than expected air, and lost altitude too quickly as it tried to land in the compound. Its tail caught the concrete wall and broke off the rotor, forcing the pilot to crash-land, nose jammed down into the dirt. The Seals quickly climbed out of the side doors, rifles at the ready.

Not knowing what had happened, the pilot of the second helicopter pulled back. The plan had been for Razor 2 to hover over the roof of the house so the Seals could rappel down and surprise bin Laden while he slept. Instead it landed outside the compound and they used explosives to blast the metal gate.

The Seals dashed through the hole. At the end of the drive they saw a small, shoebox-shaped guesthouse. A man ran out waving an AK47. This was Ibrahim, the courier. Before he could take aim they shot him, then ran towards the main house. Ibrahim’s brother Abrar rushed out with an AK47 and his wife Bushra. Both were shot.

Meanwhile the Seals from the first helicopter had run inside the house and were going from room to room, not knowing if the place was booby-trapped. As one group headed up the stairs they encountered bin Laden’s twenty-three-year-old son Khalid, and shot him dead. At the top a man’s head poked out from behind a curtain to see what the commotion was. Through their night-vision goggles the Americans could see it was bin Laden. Two women rushed out, presumably bin Laden’s two elder wives, and the Seal who was point-man of the team moved to block their way with his body, even though they could have been wearing suicide vests. Two other Seals, Rob O’Neill and Matt Bissonnette, followed bin Laden into the bedroom.

His youngest wife Amal screamed and threw herself in front of him. Bin Laden’s AK47 was by the side of the bed, but before he could reach for it one Seal shoved Amal aside, and the other fired a shot, grazing her in the calf. The two men were less than two feet away from bin Laden as they fired at him – ‘bap, bap’ – a kill shot to the head, near the left eye, blowing out the back of the brain and cutting the spinal cord, followed by a second to the chest. The al Qaeda leader crumpled to the floor as he was shot a third time.

The Seals took photos for identification, then dragged the body out of the house and loaded it into a nylon body bag. It was then taken onto the helicopter, where a medic took swabs for DNA confirmation that it was indeed bin Laden.

On the audio feed the Seal team commander gave the agreed codeword, ‘Geronimo,’ then repeated ‘Geronimo EKIA’ – Enemy Killed in Action. Back in the Situation Room at the White House there were gasps. ‘We got him,’ said Obama quietly.

While this was going on, other Seals were running through the house gathering up papers, five computers and more than a hundred thumb drives. Altogether these contained more than 6,000 documents that intelligence officials would refer to as a ‘treasure trove’ which they hoped might stop further attacks. Another team went to the damaged helicopter and smashed the avionics, then wired it up with explosives so no one could steal the technology. As soon as the Chinook and the surviving Black Hawk had lifted off the timer was triggered to blow it up, though its tail remained embedded in the wall.

The tension was not over, however, for Operation Neptune’s Spear was not yet finished – the Seals still had to get out of Pakistan.

The Americans were both relieved and astonished by the lack of Pakistani response. Back in January, when the Seal Team Six commander was first flown to a secret underground bunker and told to prepare for a raid on a ‘high-value individual’, bin Laden’s location had been described as a ‘non-permissive environment’ for American forces. The commander initially assumed this meant Iran. Pakistan, after all, was an ally.

However, relations had deteriorated even further at the start of the year when a CIA contractor called Raymond Davis shot dead two Pakistanis in Lahore who had been following him. Davis had been trying to penetrate Pakistani militant factions like LeT, and the two men had approached him at an intersection on a black motorbike with their guns trained on him. He took out his Glock pistol and shot them through his car window.

When Davis was arrested the police found that his camera, which was in the car, had photographs of military installations. This was regarded by Pakistanis as proof of widely reported rumours in the media that the CIA was sending a vast secret army to Pakistan.

Davis claimed that he worked at the American Consulate as ‘a consultant’, and Obama said he was a diplomat. Clearly no normal diplomat would be carrying a Glock, and the ISI chief General Pasha was furious when Leon Panetta insisted, ‘He’s not one of ours.’ Davis was kept in a Lahore prison which had a reputation for people dying in unexplained circumstances.

The crisis continued for two months, worsening when the widow of one of the dead men committed suicide. Eventually the US admitted that Davis was working for the CIA, and paid 200 million rupees (about £1.44 million) in blood money, enabling him to be flown out.

The very next day, 17 March, the CIA launched a massive drone attack in North Waziristan, killing at least forty people attending a tribal meeting. It was as if they were saying, ‘We can do what we like in your country.’ I was in the office of General Athar Abbas, spokesman for the Pakistani military, when the news came in on all of his many TV screens. He was furious.

By the time of the Abbottabad raid then, six weeks later, there was so little trust between the two countries that there was no way the Americans were going to inform Pakistan’s civilian or military leadership about it. So great was thought to be the likelihood that Pakistan’s military would tip off bin Laden that the US had preferred to take the risk that the Pakistanis would think they had been invaded by India and shoot the helicopters down. It was to mitigate against that that the Stealth helicopters were used, while a navy electronic-warfare aircraft called a Prowler created a corridor for them to fly through that would not show up, and generated the fake impression of an intruder elsewhere.

Of course the helicopter crash alerted attention. General Kayani, the Pakistani army chief, was awoken and informed of it, and contacted the head of the air force. They were baffled. Pakistan had a sophisticated radar system to protect against incursions from enemy India, and they had no idea how it had been breached.

While the Pakistanis were scrambling two F16 jets to the wrong destination, the American helicopters were already carrying bin Laden’s body to Jalalabad. There, in a hangar, the Seals were met by their boss Admiral William McRaven, head of JSOC, Joint Special Operations Command, and the female CIA agent codenamed ‘Maya’ who had been fundamental to the search. Her headquarters in Langley had already confirmed from photographs, using facial-recognition technology, that it was bin Laden, but McRaven stretched out the corpse to measure it. Only then did he realise nobody had a tape measure.

Back in bed, General Kayani was woken at 5 a.m. by a phone call from his friend Admiral Mullen – by then the two men had met twenty-seven times in the previous two years – telling him what had happened. It was the first official communication of bin Laden’s killing.

Seven thousand miles away in the US capital, Americans watching Donald Trump’s The Celebrity Apprentice on what was for them still Sunday evening were surprised to see a newsflash around 10.30 p.m. Eastern Time that President Obama was to address the nation. Major newspapers were called by the White House and told to ‘Hold the front page.’

I was at home with my family, and we had just finished dinner with my mother, who had arrived from England that afternoon. As we speculated about what had happened, the last thing we thought about was Osama bin Laden – the al Qaeda leader had been hidden so long that he had dropped off radar screens.

A revolution was under way in Libya, the latest in the Arab Spring, and NATO jets had been bombing regime targets, so some journalists thought perhaps the Libyan dictator Colonel Muammar Gaddafi had been killed. But that seemed an unlikely reason for the US President to give a late-night address to the nation – Obama had been reluctant even to get involved with Libya.

It was Twitter, not traditional media, that first broke the news to the world. Keith Urbahn, a former Chief of Staff to Donald Rumsfeld, tweeted at 10.24 p.m.: ‘So I am told by a reputable person that they have killed Osama bin Laden. Hot damn.’

Word started to spread, and fifty-seven million Americans tuned in to hear Obama just over an hour later. Standing at a podium on a red carpet in front of the East Room, he announced, ‘Tonight, I can report to the American people and to the world that the United States has conducted an operation that killed Osama bin Laden, the leader of al Qaeda, and a terrorist who’s responsible for the murder of thousands of innocent men, women and children. A small team of Americans carried out the operation with extraordinary courage and capability. No Americans were harmed. They took care to avoid civilian casualties. After a firefight, they killed Osama bin Laden and took custody of his body.’

Nine years, seven months and twenty-two days after 9/11, the world’s most expensive manhunt had been brought to an end with a thirty-eight-minute operation. Contrary to what Obama had said, there had been no firefight. In fact one of the Seals would later say that only twelve shots were fired in the entire operation.

Jubilant crowds gathered outside the White House, chanting ‘USA, USA!’ and ‘CIA! CIA!’ One placard read ‘Obama 1 Osama 0’. Most of those there were students from the nearby George Washington University who should have been revising for their yearly exams, and who had grown up under the shadow of 9/11. Pilots on domestic airliners, al Qaeda’s weapon of choice against America, announced the news to cheers from passengers.

For the Obama administration the first challenge was what to do with the corpse. Conscious of the damage done to the reputation of the US by Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo, it had been drummed into the Seals that there should be no disrespecting the body, no kicking it or any triumphal photos. After consultation with the Saudis it was flown to an American warship, the USS Carl Vinson, in the Gulf just off Pakistan. There it was wrapped in a white burial shroud laden with weights, Muslim rites were administered, and at around 2 a.m. DC time it was tossed into the Arabian Sea.

Amid all the celebration there was a nagging doubt. For almost ten years the US had been fighting a bloody war in Afghanistan, the aim of which officials had repeatedly said was to ‘disrupt, dismantle and defeat al Qaeda’. Two million American soldiers had been deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq, and more than 100,000 of them were still engaged in Afghan valleys and plains, from Helmand in the south-west to Mazar-i-Sharif in the north. By contrast, Pakistan, where bin Laden had found refuge, was meant to be Washington’s ally, and had received more than $20 billion in civilian and military aid over the last ten years.

In Obama’s speech he mentioned Pakistan several times, but was careful with his words. ‘Over the years, I’ve repeatedly made clear that we would take action within Pakistan if we knew where bin Laden was. That is what we’ve done. But it’s important to note that our counter-terrorism cooperation with Pakistan helped lead us to bin Laden and the compound where he was hiding.’

Within a few days many people would be asking the same question: How on earth had bin Laden been living for more than five years in an army garrison city, on army-managed land, down the road from Pakistan’s top military academy, just fifty miles from the country’s capital?

I spent the next few days in Washington, where everyone seemed to want to give their version of events, leaking so many details that the CIA complained they were compromising future operations. Then I flew to Islamabad to try to get some answers.

I landed in a nation in shock. Not shock that the al Qaeda leader had been living with his family in a house so close to the capital, but that America had carried out a brazen raid on their territory, particularly after US–Pakistan relations had been poisoned so much over the Raymond Davis affair.

I headed for the Marriott, which had been rebuilt after the 2008 bombing and looked more like a fort than a hotel – indeed, it was claimed to be the most protected hotel on earth. There I had lunch with one of the country’s most senior diplomats, Riaz Khokar, who had been Musharraf’s Foreign Secretary from 2002 to 2005, and previously Ambassador to Washington. ‘People are very disappointed – they are all asking, how could the US do this to us?’ he said. ‘In the mosques on Friday nobody was talking about anything else. My butcher today said America has invaded us, and I have no answer to that. The US has got a huge trophy, but it has left a huge crater of distrust.’

Eventually I managed to get him to address the key question – how could bin Laden have been living in Abbottabad without ISI being aware of it? ‘Intelligence agencies wouldn’t be intelligence agencies if they didn’t engage in monkey business,’ he replied. ‘But what benefit did Pakistan have in keeping bin Laden? He was a liability, he declared war on Pakistan. Would we do that for $1.5 billion a year?’

Also in the Pakistani capital at the time was Marc Grossman, who had become US Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan after the sudden death of Richard Holbrooke. He described the atmosphere as ‘surreal’, and later told Husain Haqqani, Pakistan’s Ambassador to Washington, that he felt Pakistani officials and the rest of the world seemed to exist in ‘parallel universes’. ‘As Pakistan’s Ambassador to the US at the time, I could not tell Grossman that I agreed with him,’ said Haqqani. ‘But like many Pakistanis who worry about their country’s future, I have often noted my compatriots’ tendency to live in a world all our own.’

Another old friend, Nusrat Javed, who hosted a nightly television phone-in show, was so frustrated that all the calls were only about the ‘outrageous attack by the US’ that he got a journalist friend to call in pretending to be a member of the public and ask, ‘How on earth was the world’s most wanted terrorist living in our midst?’ Even though the friend had called the programme not from his own phone but from a phone-box in a market, he was quickly contacted by ISI and warned, ‘We know who you are and what you did.’

As usual, conspiracy theorists took over. Many people simply refused to believe that bin Laden had been living in Abbottabad. One national daily, the Pakistan Observer, ran a front-page story claiming that he had died years before, and his body kept in a fridge at Bagram airbase: ‘The body of frozen Osama was brought to Abbottabad by a helicopter under the most sophisticated and hi-tech operation and taken to the upper storey of the building. A commando immediately sprayed a blood-like solution on his face to establish that the leader of al Qaeda was killed on the spot.’1 According to this story, the raid had been faked by the CIA to embarrass Pakistan, enable the US to hasten the withdrawal of its forces from Afghanistan, and boost Obama’s election prospects for the following year.

Many people I met again told me the old story I’d heard so often in 2001: that bin Laden wasn’t behind 9/11 in the first place, but that Mossad had carried out the attacks as an excuse to launch an American-Israeli crusade against the Islamic world.

I was of course eager to see bin Laden’s house, so on my second day I headed off to Abbottabad, a two-hour drive from the capital. I had been there before, and remembered it as a genteel green town in the foothills of the Himalayas at the start of the Silk Road to China. The town was founded in 1853 by a British officer, James Abbott, who penned odes to the ‘sweet Abbottabad air’. Until the Obama raid it was mostly known for its good schools and golf courses.

I had forgotten how much of a garrison town it was. As I drove in, I passed the pennant of one regiment after another – ‘Home of the Pathans’, ‘Home of the Baluch’ … – as well as the Army Boys’ School and the Combined Military Hospital. Road signs requested, ‘Please Keep the Cantonment Clean’. I took a right turn for the Kakul Military Academy, the West Point of Pakistan, which had an army checkpoint and a sign warning ‘Restricted’. Just before the checkpoint was a turn-off to the right, past a deserted strip of land, to Bilal Town, where bin Laden had been living.

House No. 3, Street 8A, Garga Road, was easy to find. The White House had described it as ‘a luxury one million dollar mansion, about eight times the size of neighbouring houses’. It was indeed large, and was surrounded by twelve-foot-high walls topped with concertina wire – but so were many houses in the area: Pashtuns often live in fortified houses because of feuds, and local people had just assumed the two brothers in the house were smugglers.

The area had been cordoned off by police and plain-clothes men, but I managed to convince them to let me through. The compound was a strange triangular shape – the CIA believed it had been designed to thwart surveillance – and a hole had been blasted through the front wall, where the Seals had gone in. The helicopter rotor fin had been removed: Pakistan had handed it over to the Chinese, to annoy the Americans.

Inside the walls stood the three-storey house. It was strange looking up at this place where the world’s most wanted man had lived for nearly six years, never coming out except for walks around the garden. The top floor had windows on only one side and a terrace with a seven-foot wall, and it was there that bin Laden had stayed with his youngest wife, Amal, a Yemeni he had married in 2000 when she was just seventeen, and who had since had five children. Two of them were born in the local hospital in Abbottabad, the Interior Minister Rehman Malik told me.

On the second floor lived his other wives, both Saudi – his second and eldest wife, Khairiah, by then in her sixties, and the mother of his twenty-year-old son Hamza, who had two children of his own; and third wife Siham, mother of Khalid. Khairiah had been under house arrest in Tehran after 9/11, but somehow in 2010 she had travelled the 1,500 miles from there to Abbottabad. Both she and Siham were well educated, with doctorates, and gave lessons to the children every day.

The house certainly wasn’t a million-dollar luxury property. Indeed, although bin Laden was the son of a billionaire, for many years he had lived an austere life. His first wife, Najwa, who left him, had complained that when they lived in Sudan in the early 1990s he refused to have air conditioning or toys for their children. The Abbottabad house had no air conditioning and just a few gas heaters, so it must have been unbearably hot in summer and bitterly cold in winter.

The family were quite self-sufficient. They kept chickens for eggs and cows in sheds for milk, and grew vegetables. Two goats were delivered to the house every week and slaughtered for meat, and there was a supply of cooking oil and Quaker oats for porridge.

Local people had been warned off not to talk, but some neighbours nervously exchanged a few words. No one had ever seen bin Laden or any of the children. They told me that if a local child accidentally hit a cricket ball over the compound’s wall and knocked at the gate they would not be allowed in, but would be given money to buy a new one.

Only two men ever came out of the compound – Arshad and Tariq Khan, as they were known locally. Their real names were Ibrahim Abu Ahmed (‘al Kuwaiti’) and his brother Abrar. A local shopkeeper told me he sold them John Player cigarettes, which they bought in singles, suggesting they had little money. It was the brothers who had bought the land in 2005 and built the house, and they lived in a separate house in the compound with their own wives and children. They and the bin Ladens moved in sometime in 2006. No one seemed to know where bin Laden had been between fleeing Tora Bora in December 2001 and then, though he apparently lived for a while in Swat until the 2005 earthquake.

Bin Laden’s self-imposed confinement in the Abbottabad compound must have felt very restrictive for a man who loved the outdoor life, riding horses and striding over mountains. His only exercise was walks in the garden, which had a tarpaulin over it so he could not be seen from above. He also wore a cowboy hat to cover his face.

What did he do all day? Only seventeen of the thousands of documents retrieved from inside the compound were later made public, but these showed that he had more control over al Qaeda than had been thought. ‘Bin Laden was far more operationally active and hands-on than we realised,’ Obama’s counter-terrorism czar John Brennan told me. He wrote letters to al Qaeda affiliates such as al Shabaab in Somalia and AQAP in Yemen, and called for suggestions for the tenth anniversary of 9/11. He compiled an annual review, the last of which, in October 2010, was upbeat about Afghanistan, where he wrote that the Americans had suffered ‘the worst year since they invaded’, and predicted that economic pressure would mount on the Obama administration to withdraw. He was, however, suffering his own financial woes. Like the CEO of a company, he had a financial division, and this seemed to be cash-strapped. Allowances were slashed, and he asked for receipts for everything, even thumb drives costing a few pounds.

It was also clear that the drone programme was having a serious impact on the organisation’s ability to move around or to organise major new attacks on the West – the last had been the London bombings in July 2005. He advised followers in Pakistan’s tribal regions not to travel except on overcast days, ‘when the clouds are heavy’, or to meet in tunnels. ‘I am leaning towards getting most of our brothers out of the area,’ he wrote.

‘We know from the material from the compound that OBL himself recognised they were being pummelled,’ said Brennan. ‘He wanted to carry out more attacks, but his commanders were saying, “Your aspirations outweigh your capabilities.”’

A week after the raid, US officials released a video found in the house of a white-bearded bin Laden huddled on the floor in a brown blanket in front of a cheap TV set, using a remote control to watch news clips about himself. They also revealed that they had found packets of ‘Just for Men’ black hair dye, which he was using to cover up his grey hair and beard. It was hardly the final image the world’s most media-conscious terrorist leader would have chosen.

What was most astonishing was not the size or the appearance of the house, but its location. Not only was Abbottabad a military town not far from Pakistan’s capital, but the house was on land managed by the military and literally just a few hundred yards from the country’s most prestigious military academy. General Musharraf said he used to go running past the house. General Nadeem Taj, his close ally, and head of ISI from 2007 to 2008, had been commandant of the academy in 2006, the year bin Laden moved there. The army chief General Kayani had addressed cadets at their annual passing-out parade. US special forces had even been based there for training in 2008.

The other odd thing was that bin Laden was not living like a man who might one day have to flee at a moment’s notice. He had no guards and no escape route, no Tora Bora-style tunnels. He lived as if he thought he was protected, and expected to be forewarned of any danger. The only precautions the Americans found were a few hundred euros and two phone numbers sewn into his pyjamas. Letters taken from the house and later released talked of ‘our trusted Pakistani brothers’, suggesting he was in touch with local militant groups.

Just as few believed it was possible for so many militant organisations and terror groups to exist in Pakistan unless major elements in the state machinery were protecting them, Brennan said, ‘It’s inconceivable that he didn’t have a support network in Pakistan helping him.’

Tracking down bin Laden was an incredible coup for the CIA. The Agency was under something of a cloud, having been caught flatfooted by the Arab Spring, misjudged Saddam’s supposed weapons of mass destruction leading to the ill-judged invasion of Iraq, and tried to justify the use of torture in interrogating detainees.

A few years earlier, in 2006, I had done a story about the hunt for bin Laden, and it was clear then that many in the Agency thought it had reached a dead end. They had taken to referring to bin Laden as ‘Elvis’. Under fire for botched intelligence assessments about WMD in Iraq and the use of ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’, Agency morale was low.

However, the bin Laden cell did not give up, and a few things had caught their attention. Other senior al Qaeda figures had been apprehended while living in Pakistani cities, not in caves as popularly thought. The last senior figure to be caught, Abu Faraj al Libbi, picked up in May 2005, had been waiting at a shop in Mardan (not far from Abbottabad), which was a drop point for a ‘designated courier’ of bin Laden.

It was well known that bin Laden had stopped using phones and the internet, because these were easily intercepted and had led to others being caught. The CIA knew he used foot messengers, and around 2007 started focusing on trying to find these human carrier-pigeons. ‘We had cued onto the notion of the network being the holy grail to burrow into al Qaeda’s senior leadership,’ said Juan Zarate, who was Deputy National Security Adviser for Terrorism in the second term of the Bush administration. ‘We had enough information to suggest there were a couple of trusted couriers being used by OBL.’

The problem was, they didn’t know who they were. They first heard the name ‘al Kuwaiti’ in 2003, from the interrogations in Guantánamo of a Saudi called Mohamed al Qahtani. Qahtani was supposed to be the twentieth 9/11 hijacker, but had been refused entry to the US by an eagle-eyed customs official at Orlando airport, suspicious of his one-way ticket. He was picked up fleeing from Tora Bora in December 2001 and sent to Guantánamo, where he initially claimed he had gone to Afghanistan because of his love of falconry. Someone made the connection to the man who had been turned away at Orlando, and for a period of forty-eight days starting in November 2002 he was interrogated and tortured, subjected to sleep deprivation and freezing temperatures and forced to listen to loud music by performers including Christina Aguilera.2 At some point he mentioned the name ‘Abu Ahmed al Kuwaiti’, but that was just one of hundreds of names being entered into a massive database. The name came up again in the interrogations of other detainees, including an al Qaeda lieutenant, Hassan Gul, who said al Kuwaiti was close to KSM and al Libbi. When KSM was questioned about him during his endless waterboarding sessions he described him as ‘retired’, which seemed odd. Al Libbi said he had never heard of al Kuwaiti. Investigators wondered if the two men were deliberately steering them away from him. However, they could not track him down, and thought he might be dead.

By 2009 the NSA was blanket monitoring phone calls in the region, and someone else on the Agency’s radar in the Gulf made a phone call to a man they realised was al Kuwaiti. The man asked what al Kuwaiti was up to. ‘I’m back with the people I was with before,’ he replied. There was a pause on the line, then the friend said, ‘May God facilitate.’

At the time numerous phone conversations were being intercepted in the area with the help of ISI. The CIA did not share the significance of al Kuwaiti with the Pakistani agency. They tracked his phone down to north-west Pakistan, but they could not pin down his location. Knowing his phone could be used to trace him, al Kuwaiti only put its batteries in and switched it on when he was at least ninety minutes away from Abbottabad. But then in August 2010 a Pakistani asset working for the CIA tracked him to Peshawar, and followed his white Suzuki jeep to the compound.

As soon as they saw the pictures of the house in Abbottabad the CIA team were intrigued. The house was well-fortified, and strangely had no phone or internet connection. Locals said the occupants burned their own rubbish. The CIA became convinced that someone important was hiding there, and started monitoring it with an overhead drone.

The difficulty was knowing what was going on inside the house. One agent came up with the idea of staging a fake polio drive, using a Pakistani physician, Dr Shakil Afridi, so they could obtain samples of blood from the children living there. They never managed to get any.

They also set up a safe house to monitor comings and goings, and a blimp overhead. From this they saw that a tall man often walked in the garden. They nicknamed him ‘the Pacer’. When they measured his shadow they found that he was over six feet tall.

Excitement in the unit started to mount. Though they had no actual sighting of bin Laden’s face, they became convinced that he was there. CIA Director Leon Panetta told Obama that this was the best ‘window of opportunity’ since Tora Bora.

Biden and Gates were sceptical. Both men recalled ‘Black Hawk Down’, the 1993 débâcle in Somalia when two US helicopters were shot down, as well as the failed helicopter mission to rescue hostages from Iran in 1980.

Though he had to admit the chances were only ‘fifty-fifty’, the usually cautious President took the riskiest decision of his administration. On Friday, 29 April 2011, while much of the world was watching the royal wedding between Prince William and Kate Middleton at Westminster Abbey, he called McRaven. ‘It’s a go,’ he said.

Obama’s gamble paid off, but for Pakistan the discovery of bin Laden had opened up an enormous can of worms. How could ISI, which monitored everything we journalists did, not know that the world’s most wanted man was living under its nose? Pakistan’s intelligence service was either ‘complicit or incompetent’, declared Panetta. Neither was a good place to be. Most people assumed the former. Musharraf after all had once said Pakistan’s military was so strong that ‘Not a single rifle bolt can go missing without us knowing.’3

I asked former Republican Congressman Pete Hoekstra, who as Chair of the House Committee on Intelligence from 2004 to 2007 had been privy to intelligence from the region, for his view. ‘Finding bin Laden in Pakistan was not exactly a Casablanca moment: “Shock! There’s gambling in the casino!”’ he said. ‘I believe there were people in ISI and the military who knew he was there. The question is, how high up does it go?’

Some even speculated that there was a bin Laden desk inside ISI, run by some of the old ideologues, though most believe it more likely that he was protected by one of the militant groups close to the agency.

Lieutenant General Asad Durrani, who ran ISI in the 1990s and later served as Ambassador to Germany and Saudi Arabia, said it was possible the agency did know, and were planning to reveal Osama’s whereabouts when it suited it. ‘The idea was at the right time his location would be revealed,’ he told the BBC’s Hardtalk. ‘And the right time would be when you can get the necessary quid pro quo – if you have someone like Osama bin Laden you are not going to simply hand him over to the United States. Double game is the norm. I think it was Lord Robertson, former Secretary General of NATO, who said, “If you can’t ride two horses, don’t join the circus.” Statecraft isn’t about following a linear path, you play so many games, you keep so many balls in the air.’4

‘Who was hiding him is the $64 million question,’ said Bruce Riedel, the former CIA analyst who headed Obama’s AfPak review. ‘He lived in Pakistan nine years, moved at least three times, was having kids like a twenty-year-old, and his wife gets out of whatever detention in Iran and knows how to find him. We also know he was communicating with LeT and Hafiz Saeed. There are three options: ISI were clueless; or they knew exactly where he was and were protecting him; or something in between – they knew he was somewhere in Pakistan, and his friends in LeT and other militant groups were communicating with him and protecting him.’

There was outrage in the US Congress, which over the years had voted so many billion dollars in aid to Pakistan. Dana Rohrabacher, a Republican Congressman from California, spoke for many when he called for aid to be cut off: ‘They were playing us for suckers all along. I used to be Pakistan’s best friend on the Hill but I now consider Pakistan to be an unfriendly country to the US. We’re giving money to someone who obviously is working against the national security interests of our own country. They’ve been arming these people [Taliban] to kill our troops, they’ve been building nukes at our expense and now we know they have been giving aid and comfort to bin Laden. We were snookered. For a long time we bought into this vision that Pakistan’s military were a moderate force. In fact the military is in alliance with radical militants.’

Once again, as with the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, there were a lot of coincidences. Yet no smoking gun was found linking ISI to bin Laden. ‘There’s a very powerful circumstantial case, but in the end that’s all it was,’ said Riedel. David Kilcullen, the counter-terrorism expert, agreed: ‘Let’s assume they knew where bin Laden was in 2002 and gave him up. Then they don’t get the money and influence and are seen as a basket case by the international community. They had every interest in the world to preserve al Qaeda, not destroy it.’ He went further: ‘I went from thinking they were playing both sides to thinking they were backing the other side to realising they are the other side.’

Over the following years I asked everyone I met who had access to the intelligence trove, but all insisted that nothing had been found. I wondered if people were lying. After all, as Riedel pointed out, if the Obama administration did find a smoking gun which proved Pakistani complicity, that would be a political nightmare. ‘What would you do then?’ he asked. ‘When we say to the Pakistanis, “You’ve got to stop allowing IEDs being made in your backyard or else,” what is the “or else”? We’re not going to go to war with them, that’s for sure. There’s no credible “or else”, and Pakistan knows that.’ Referring to how the Libyan revolution might have had a very different outcome had Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi not previously handed over his nuclear weapons programme in a 2003 deal with the US and the British, he said, ‘The Pakistanis watched what happened to Gaddafi, and said, “That won’t happen to us because we kept our nukes.”’

In fact Pakistan had been quietly ramping up its programme, doubling its stockpile of bombs to more than a hundred; by the time of the bin Laden raid it had overtaken Britain and France to be the world’s fifth largest nuclear power.

Once again the prevailing view was that Pakistan was too dangerous to cut off. Before I went back to Washington I met a very senior ISI official. ‘You know we built up our nuclear arsenal against India, but now they turn out to be very useful in our dealings with America,’ he said, smiling like a Bond villain.

Inside Pakistan, some believed that the humiliation of ISI provided an unprecedented opportunity for the civilian government to finally exert authority over the military. ‘The game is up,’ proclaimed the Daily Times, arguing that ‘Pakistan’s military cannot afford to play its usual double game any more’ of supporting militant groups. It also called for parliamentary scrutiny of the military and ISI budgets.

Farahnaz Ispahani, an MP and spokesperson for President Zardari, told me she had gone to him saying, ‘This is our chance.’ She suggested that he announce a commission of inquiry. He did nothing, then the next day she read in the press that General Kayani had announced the military’s own commission. ‘We lost the chance,’ she said.

General Pasha and General Kayani, as chiefs of ISI and the army, went to explain themselves in an unprecedented closed-door session of parliament on 13 May 2011. Pasha told the MPs he took responsibility, and offered to resign, but Kayani refused. He described the agency’s ‘key role in safeguarding the country’ since its beginning, and warned that criticising the army and ISI would be ‘against the national interest’.

Nothing happened. After the session Dr Firdous Awan, the Information Minister, told the press that parliament was aware of the ‘critical times’ being faced by the military, and had agreed to stand united behind it. ‘They should be assured that they are not alone and the whole nation is behind them,’ she said.

Surprisingly, it was only the opposition leader Nawaz Sharif who spoke out – a man who had started his political career as a protégé of the army, placed in power by General Zia. This was, he said, ‘a historic opportunity [for the government] of tilting the power in favour of civilians’. He added, ‘It is time for the agencies to work within their constitutional ambit instead of subverting the constitution, toppling governments, running parallel administrations and controlling foreign policy.’

The government did nothing. The day after the bin Laden raid, the Prime Minister Yusuf Raza Gilani took off for Paris.

I was told that ISI had a series of videos implicating Ministers in everything from accepting kickbacks to footage of the wife of one of them gambling large sums in a London casino, which they threatened to release.

The army and ISI were fighting back. My Pakistani mobile was bombarded with text messages. ‘Brothers come to Islamabad Press Club at 4 p.m. to rally to express solidarity with Pakistan army and ISI which have become targets of false propaganda by enemies of Pakistan,’ read one. ‘CIA failed to learn about Pearl Harbor; CIA failed to warn Americans about 9/11; CIA gave false info of WMD in Iraq; Long Live Pakistan Army,’ read another. The name of the CIA station chief in Pakistan was leaked by ISI to press. A number of people were arrested, including the doctor who led the fake polio-vaccination drive aimed at flushing out bin Laden. He was later sentenced to thirty-three years in prison.

I began to feel as if I was living in a parallel universe. I went to see General Hamid Gul, and reminded him how he had spoken to me after KSM’s capture in Rawalpindi about the advantages of ‘hiding in plain sight’. ‘Yes, of course,’ he replied. ‘No one would have expected Osama living in a town with twenty children.’ For a moment I thought we were agreeing. Then he continued, ‘But it wasn’t bin Laden. He died a long time back, 2004 I think. The Americans just wanted an excuse to blacken the name of Pakistan and hide the fact they botched this thing up. 9/11 happened on CIA’s watch. What about the WMD in Iraq? Now this confusion in Afghanistan. Don’t the CIA know that the Afghan Taliban is not the same as al Qaeda? So many bloody failures. It’s very convenient to blame Pakistan ISI. This humiliating and dishonouring Pakistan after all the services we rendered is shocking. We shouldn’t be surprised. Remember, it was the Americans who blew up Zia, you were here then. As General Ayub said, “It may be dangerous to be America’s enemy, but to be America’s friend is fatal.”’

There were enough unexplained disappearances in Pakistan for it to be obvious that investigating links between ISI and al Qaeda was highly dangerous.

It was my birthday while I was in Pakistan, and a friend held a party for me to which a number of Pakistani journalists came, bearing colourful bunches of gladioli, for it was that time of year. Of course the only topic was bin Laden’s killing and who had been protecting him. Everyone warned me off investigating. One brave exception was Saleem Shahzad from the Asia Times, who had written before about the link between ISI and al Qaeda. Two weeks later, on Sunday, 29 May, the forty-year-old father of three was abducted in broad daylight in Islamabad on his way to do a TV interview. Two days later his body was found on a canal bank in Mandi Bahauddin, about eighty miles away, bruised and battered. He had been beaten to death. ‘Any journalist here that doesn’t believe that it’s our intelligence agencies?’ tweeted Mohammad Hanif. Saleem had told colleagues a year earlier that he had received threats from ISI. Admiral Mullen told journalists in Washington a few weeks later, ‘It was sanctioned by the government.’

Pakistan had become the most dangerous place on earth to be a journalist. Nine were killed that year, and nobody brought to justice. Anyone who had worked in journalism in Pakistan was only too familiar with ISI control. Whenever there was a major story, editors were given ‘guidance’ on what line to take. Nobody could afford not to listen. TV and radio stations were dependent on licences from the regulatory body PEMRA, which could be revoked, and newspapers on print from the government as well as advertising.

I had first realised the extent of this control when I was deported in 1990, and journalists I’d considered friends wrote astonishing scurrilous stories about me ‘entertaining’ local politicians in the Holiday Inn. ‘How could you write this?’ I asked them later. ‘You knew none of it was true.’ They shrugged. ‘We had no choice, you know that.’ In the Zia years under censorship, papers often appeared with stories blacked out and there was only state-controlled TV. Under Musharraf it became much more sophisticated. He had allowed private TV channels, and a slew had opened, so it looked to be free. But they depended on the government to stay on air, and ISI encouraged the media to whip up the anti-American frenzy over drones and ‘violation of sovereignty’, even though Musharraf had actually agreed to the programme.

Kamran Shafi, a former army officer and diplomat turned journalist, described relations between the media and the authorities as ‘wheels within wheels, shadows within shadows, mirrors within mirrors’. As an outspoken commentator, he regularly received threats, phone calls telling him, ‘You are dead … you will be shot and dragged on the streets.’ When he called in print for ISI to be headed by a civilian, shots were fired outside his home.

‘When you work as a journalist in Pakistan you feel Big Brother is watching you all the time,’ said another friend, Malik Siraj Akbar, who set up the first online newspaper in his home province of Baluchistan. ‘If you host or help a foreign journalist then you should prepare to be called by ISI. They will immediately call you an “enemy of the state” and threaten you with dire consequences. Many journalists in our ranks are on the ISI payroll, and you don’t know who among your own colleagues or bosses, which makes it difficult to openly express your opinion even at the press club or social gatherings. It’s very hard to bring an end to ISI’s domination as long as top politicians and journalists willingly serve as paid agents of ISI.’

He was subjected to years of harassment and threats for writing about ‘disappearances’ in Baluchistan, and was eventually forced to flee the country in October 2011 and seek asylum in the US. The harassment started in the summer of 2007, when he was forcibly picked up from the Quetta Press Club and taken to the military cantonment. ‘I was questioned for several hours by a Major and Colonel who had marked stories with green highlighter and demanded to know my sources of funding for my paper, and warned me to stop writing about disappearances.’

That was the first of many sessions. Another time he was intercepted by an agent at the hotel in Lahore where he was staying on the way to a conference in India to speak on Baluchistan. ‘He warned me of dire consequences if I went. When I returned the same agent was waiting for me at Lahore airport with a couple of other men. I immediately grabbed the German organiser of the conference, who had travelled back on the same plane.’

The threatening sessions did not stop, and his website was frequently blocked. Worst of all were the untraceable phone calls. ‘When an anonymous caller tells you the colour of your T-shirt or comments on your new haircut, fear grips more deeply,’ he said. These were not idle threats. ‘I lost a dozen journalist friends in one year in Baluchistan.’

Nor was size any protection. In 2013 when the country’s most-watched TV channel, Geo, dared to suggest that ISI might have been involved in an assassination attempt on its highest-profile anchor, Hamid Mir, ISI called for the channel to be taken off the air, and it was. The message got through. Instead of supporting Geo, other channels lined up to attack it.

The killing of bin Laden did not improve the situation in Afghanistan. The month after his death a group of militants in suicide vests and armed with RPGs and grenades burst into the Intercontinental Hotel in Kabul while a wedding party was under way. They held guests under siege for five hours as police and commandos battled to take control, supported by NATO helicopters overhead. At least twenty people were killed. In July a US helicopter was shot down in Wardak, around forty-five miles from Kabul, killing thirty US soldiers. Then, in the same area, a massive truck bomb was driven into a base on 10 September, killing five Afghans and injuring ninety-six people, including seventy-seven Americans. This was followed by a twenty-hour siege on the highly guarded US Embassy and ISAF headquarters in Kabul on 13 September. If it wasn’t quite the spectacular bin Laden had been calling for to mark the ten years since 9/11, it showed the ability to get into the heart of the capital, and there was plenty of carnage.

US officials said phones recovered from the scene had been used to call numbers associated with the Haqqani network and ISI. Admiral Mullen was just about to retire, and finally lost patience with the country he had tried so hard to befriend. Before stepping down, he told the Senate Armed Services Committee that he had evidence these attacks were carried out by the Haqqani network with the cooperation of ISI. He then launched an unprecedented attack on Pakistan: ‘Extremist organisations serving as proxies of the government of Pakistan are attacking Afghan troops and civilians as well as US soldiers. The Haqqani network for one acts as a veritable arm of ISI. By exporting violence they have eroded their internal security … undermined their international credibility and threatened their economic wellbeing.’

The year after the bin Laden raid, Pakistan bulldozed the Abbottabad house to try to obliterate his memory. His wives and children were flown to Saudi Arabia. His son Hamza, who was not at the house that night, was never found.

Pakistan launched its own investigation into the affair, the Abbottabad Commission. Its report, published in 2013, said ‘collective incompetence and negligence’ by the intelligence agencies was the main reason bin Laden remained undetected. However, it could not rule out some degree of ‘plausibly deniable’ support at ‘some level outside formal structures of the intelligence establishment’. Among the testimony was a statement by the ISI chief General Pasha insisting, ‘the main agenda of the CIA was to have the ISI declared a terrorist organisation’.

Killing bin Laden ended up being the most memorable achievement of the first term of the Obama administration. When the President later met Admiral McRaven, he presented him with a tape measure mounted on a plaque. Then he flew to Fort Campbell in Kentucky to personally thank Seal Team Six and the helicopter pilots. They presented him with a framed American flag that had been on the rescue Chinook, inscribed with the words ‘For God and country, Geronimo’.

He did not ask who had fired the fatal shot. Despite the Seal cult of secrecy, two men who were in Abbottabad that night would later go public – Matt Bissonnette, who in his book No Easy Day claimed to have fired one of the two shots, if not the fatal one; and Rob O’Neill, who claimed he was the actual shooter.5

With bin Laden dead and the Obama administration claiming there were only a hundred al Qaeda left in Afghanistan, it was reasonable to question why NATO still needed 150,000 troops there, continuing a war which by then had cost 1,500 American lives.

Less than two months after the raid, Obama announced his timetable for the withdrawal of the rest of the troops from Afghanistan. On 22 June 2011 he made another, less dramatic, address to the nation. Declaring that ‘the tide of war is receding’, he said he was speeding up the pullout from the surge, and would completely hand over security to the Afghans in 2014. This was against the advice of Petraeus and his generals, but Obama had other priorities. ‘Over the last decade we have spent a trillion dollars on war at a time of rising debt and hard economic times,’ he said. ‘Now we must invest in America’s greatest resource – our people.’

Within hours President Nicolas Sarkozy of France said he would start withdrawing the 4,000-strong French contingent. On 6 July David Cameron announced that he was starting to bring back UK troops, from 9,500 to 9,000 in the first year, then all those who remained by the end of 2014. Whatever the situation on the ground in Afghanistan, the war was coming to an end for the West. People began to talk of ‘Afghan goodenough’.

‘We will not try to make Afghanistan a perfect place,’ said Obama.