Proust’s father, Dr. Adrien Proust (1834–1903), around the time he married Jeanne Weil.

Mme Adrien Proust (1849–1905). Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

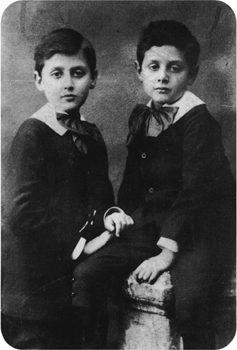

An early childhood portrait of Marcel, right, and his younger brother, Robert, in Scottish costume. Mante-Proust Collection

Marcel, left, and Robert around 1882. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Marie de Benardaky, described by Proust as “the love of my life” during his school days. They often met to play on the Champs-Élysées.

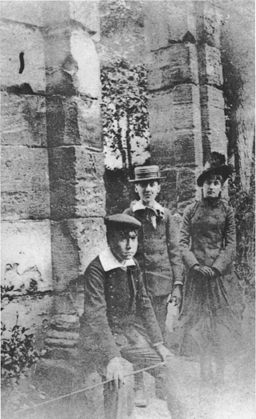

Marcel, in boater, with Antoinette Faure and another young friend in the Parc Monceau. Mante-Proust Collection

Marcel at age fifteen, March 24, 1887. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

Alphonse Darlu’s philosophy class at the Lycée Condorcet. Proust, second row, far left, is in his senior year, 1888–89. Mante-Proust Collection

Proust in the infantry at Orléans, 1889–90. Mante-Proust Collection

Robert de Billy, future diplomat and close friend of Proust’s. They met at Orléans during their year of military service. Mante-Proust Collection

Proust, seated at left, with Mme Geneviève Straus and other friends, shortly after his discharge from the army. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

During his university years Proust sports a Liberty tie and a camellia boutonniere. Mante-Proust Collection

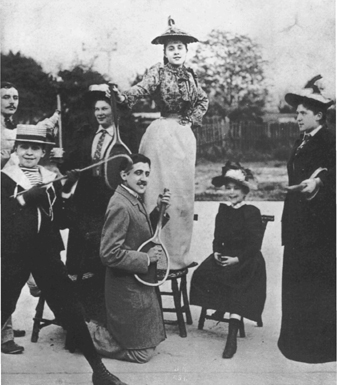

Proust at the feet of Jeanne Pouquet at the tennis court on boulevard Bineau. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Singer, pianist, and composer Reynaldo Hahn, 1898. Proust and Hahn met in the salon of Madeleine Lemaire and became lifelong friends. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

The Parisian aristocrat Comte Robert de Montesquiou, 1895. A poet, art critic, and aesthete, Montesquiou was the primary model for Proust’s baron de Charlus. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

Comtesse Élisabeth Greffulhe, 1896. A cousin of Montesquiou’s, the countess was considered the most beautiful salon hostess in Parisian society, and one of the most accomplished. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

Dr. Adrien Proust, 1886, at the height of his distinguished medical career. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Mme Proust with her sons, Marcel and Robert, 1893. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Portrait of Proust as a young socialite by Jacques-Émile Blanche, oil on canvas, 1893. Réunion des Musées Nationaux-ADAGP

Proust with friends Robert de Flers, left, and Lucien Daudet, 1893. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Mme Geneviève Straus, 1887. A society hostess renowned for her salon and her wit, she remained a close friend to Proust throughout his life. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

Laure Hayman, 1879. A celebrated courtesan of the Belle Époque, Laure was the mistress of Proust’s great-uncle Louis Weil. She inspired Proust’s creation of Odette de Crécy. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

On December 8 Proust attended a program at the Conservatory, where Saint-Saëns played the piano part in a Mozart concerto. Afterward, he drafted an essay in which he examined the performer’s effect on his audience. Around the same time, he submitted another article on Saint-Saëns to Le Gaulois and sent the composer a copy for his inspection, with the “homage of a respectful, passionate admirer,” reminding the composer that they had met in Dieppe at Mme Lemaire’s.13 Proust’s piece appeared on the newspaper’s front page on the day of the dress rehearsal of Frédégonde, an opera, left unfinished by Ernest Guiraud, that Saint-Saëns had just completed. Guiraud provided one of Mme Straus’s favorite anecdotes, which Proust would use in the Search. When she asked Guiraud, legendary for his absentmindedness, whether his love child resembled her mother, the composer replied: “I don’t know, I’ve never seen her without her hat.”14

Despite “passionate” admiration for Saint-Saëns’s work, Proust thought less highly of the composer’s accomplishments than did his former pupil Reynaldo. But the haunting melody of one section of the first movement of Saint-Saëns’s Sonata I for piano and violin, opus 75, captivated him. Marcel never tired of hearing it and asked Reynaldo to play it for him again and again, referring to it as the “little phrase.” In Jean Santeuil, where Proust uses music by Saint-Saëns for Jean and Françoise’s love song, he names the composer and the work. In the Search the same music, which Swann asks his mistress Odette to play for him again and again, is attributed to Proust’s fictional composer Vinteuil.15

On December 24 Marcel received notification that he had been granted a year’s leave from the Mazarine.16 He now had the ideal situation: a title, though modest, with no duties. In the closing days of December, Proust, increasingly frustrated by Mme Lemaire’s endless delays, wrote Hubert a series of letters aimed at compelling her to complete the illustrations. In one letter he urged Hubert to write to Mme Lemaire in a firm tone, because Marcel could do no more than pin his “hopes on the friendship of Mme Lemaire, who, since she has been holding me over the baptismal font of letters for the last four years . . . will not wish to hold me up for another year.”17 Marcel had doubled the number of years he had been suspended over the baptismal font, but for the eager young author the time spent waiting seemed far too long. By New Year’s Eve, Proust knew that he had been betrayed when he learned about a meeting earlier in the week between Hubert and Lemaire at which the editor gave the illustrator permission to continue work on new pieces. Proust worried that the additional drawings for “Fragments de comédie italienne” (Scenes from Italian comedy) would draw the reader’s eyes to the section that he considered the weakest in the book. But what riled him most was the missed opportunity to publish in February.

By year’s end Marcel and Reynaldo’s relationship had grown strained. Proust’s affection for Reynaldo remained just as strong, but he had fallen in love with Lucien. Whether during their bouts of mad laughter across the dinner table at the Daudets’ or during their meetings at the Louvre, which Lucien often visited as an art student, Proust had succumbed to the spell of Daudet’s beauty. He marveled at the boy’s features, delicate and sensual, his dreamy eyes, and his fine, olive complexion. Lucien’s family, conservative and devoutly Catholic, chose to ignore his effeminate nature.

Why and how Marcel’s passionate friendship with Reynaldo ended is not clear, but Proust’s attraction to Lucien must have played a role. Aware since childhood of the career he wanted, Hahn was pursuing his goals as a composer and performer, and he had often found his romantic relationship with Marcel too complicated and above all too demanding. He fluctuated between jealousy and exasperation about Marcel’s fussing over Lucien, who was practically a child. Marcel had just purchased an exceptionally fine article for Lucien’s New Year’s present: a beautiful eighteenth-century carved ivory box. When Lucien opened the box to admire its beauty, he felt certain that Marcel had enclosed his love.

After the holidays, Hubert remained caught between the impatient author and his meddlesome illustrator eager to correct what she considered the literary deficiencies of the work. Yielding to Mme Lemaire, Hubert wrote Anatole France a confidential letter, appealing to his “great authority,” for Marcel was unwilling to “perfect” the text. Hubert and Lemaire deplored the rambling dedication and certain pieces that were somehow too involved and without interest. Even if, as they acknowledged might be the case, these elements endowed a beginner’s work with charm, it was a charm with which they would gladly dispense.17 France, unconvinced by their arguments or unwilling to intervene, ignored the request.

Early in the new year Paul Verlaine died, depriving the nation of the man many had considered France’s greatest contemporary poet. Montesquiou was among those who spoke at the funeral on January 10. Proust, reflecting on Verlaine’s achievement while struggling with alcoholism and living in the abject poverty to which his addictions had reduced him, commended Montesquiou for having “distinguished this moving contrast . . . between heavenly poetry and a hellish life.”18 Such distinctions became paramount to Proust’s own aesthetics.

Sometime in the first quarter of the year Proust wrote the beginning pages of Jean Santeuil, in which Jean, vacationing in Beg-Meil, meets the novelist C. Marcel sent his draft to Reynaldo and asked whether it contained anything that recalled too obviously their being together, anything that was “too pony.” If so, Hahn must help him to correct those parts. Then he spoke tenderly to Reynaldo, saying that he wanted him to be present in everything he wrote, “but like a god in disguise, invisible to mortals. Otherwise you’d have to write ‘tear up’ on every page.”19 Ultimately Hahn, like Lucien, was too close a friend to serve as a model for a character in Marcel’s book, though part of the disguise Proust had in mind may be in the name of Jean’s closest friend Henri de Réveillon, whose initials are Hahn’s reversed. On March 1 a short-lived review, La Vie contemporaine, published Proust’s novella L’Indifférent. Before publication Marcel inserted, as a compliment to Hahn, an oblique allusion to his opera L’Île du rêve, for which the composer still hoped to find a producer.

Toward the end of March Proust received, at last, the first proofs of his book, bearing the title Le Château de Réveillon. In April, while correcting the final proofs, he changed the title to Les Plaisirs et les jours (Pleasures and days). He realized that using the name of Lemaire’s castle as the title of a book filled with her drawings might confuse his readers about its contents. For the new title he drew inspiration from Hesiod, whose works he had read in Leconte de Lisle’s translation. But whereas the ancient writer had called his book Works and Days, Proust replaced chores by pleasures to indicate the vain, frivolous world inhabited by his characters. Finally, the long delayed project neared completion. On April 21 Anatole France signed and dated his preface. One week later the press campaign began when Le Gaulois announced the book’s imminent publication.

Early in May, Proust dashed off a note to Lucien at Rodolphe Julian’s academy. He apologized for disturbing him during his art class again—he swore this would be the last time—and asked to meet him outside the academy. Proust inquired about Lucien’s brother, Léon, who had fallen gravely ill with typhoid fever from having eaten tainted oysters while in Venice.20 Because the disease often proved fatal, the Daudet family passed many anxious hours before it became apparent that Léon would survive. Proust informed Lucien that he had set out that morning for the Daudet home to inquire about his brother’s condition but that, on arriving in the full sunlight at the place de la Concorde, he had begun to sneeze violently and had to turn back.21

On May 10 Uncle Louis fell ill and died, at age eighty, in his home at 102, boulevard Haussmann. Marcel and his mother went to sit with the body. He sent a kind note to Laure Hayman, who had been the old man’s mistress and friend: “Madame, My poor old uncle Louis Weil died yesterday at five in the afternoon, without suffering, without consciousness, without having been ill (a case of pneumonia that had made its appearance that same morning).”22 Proust, who knew how fond Laure was of his uncle, had not wanted her to learn about his death from the newspapers. On the day of the funeral, Marcel received a note from Laure, conveying her condolences and expressing her frustration at being unable to attend the funeral without raising eyebrows. The funeral procession began in front of Louis’s home and proceeded, with the mourners walking behind the horse-drawn hearse, to Père-Lachaise cemetery. The family no doubt wished to discourage Laure’s presence at the funeral, but Marcel informed her of the time and place and protested, perhaps too much, that she would be most welcome: “But what madness to suppose you would shock anyone at all. They can only be touched by your presence.”23

To the family’s relief Laure did not attend, but just as the procession neared the cemetery, a boy, pedaling fast on a bicycle bearing a floral wreath, caught up with the mourners. Laure’s attempt to be discreet while paying her respects had not succeeded; the family had requested no flowers. Marcel wrote to Laure a few days later, explaining that only asthma and choking fits had prevented his writing sooner to tell her “how amazed, how moved and overwhelmed I was at your so touching, so beautiful, so ‘chic’ thought of the other day.” When he had found out the wreath was from her, he had “burst into tears, less out of grief than admiration. I was so hoping you would be at the cemetery so I could take you in my arms.” Marcel conveyed to Laure as tactfully as possible what happened to her offering: at the cemetery, when Jeanne heard about the flowers, she said she wanted Louis to be buried with Laure’s wreath.24 Louis had managed to leave the world enveloped in sweet fragrances from a beloved courtesan.

Jeanne and her brother Georges inherited the apartment building on boulevard Haussmann. The following year they sold the Auteuil property to a developer, who promptly razed the house and adjacent structures in order to construct several apartment buildings that occupied all the land.25 The home where Marcel and Robert had been born, the garden of their childhood, and the family summer retreat of many years had disappeared overnight.

During the year Marcel lamented the disappearance of the Auteuil property as well as his growing awareness of the effects of old age on his parents in a draft for Jean Santeuil: “Monsieur and Madame Santeuil had greatly changed since the day when we first made their acquaintance in the little garden at Auteuil, on the site of which three or four six-storeyed houses had now been built.”26 As though to underscore the passage of time, Adrien drew up his will later in the month. With his mother in mourning for her uncle, Marcel curtailed his social life for a brief period. In mid-May, he declined an invitation to a sumptuous ball given by Mme Emilio Terry at her home in the Bois de Boulogne.

Although none of Marcel’s friends considered him a Jew, he noticed that race was becoming a frequent topic of conversation and controversy in social circles and in the newspapers. Émile Zola, alarmed at the vehemence of the anti-Semite press, published an article in Le Figaro on May 16, “Pour les juifs” (For the Jews), to defend the Jews against the rabid attacks to which they were frequently subjected. Many Jews were willing to overlook outbursts of intolerance rather than defend themselves and risk setbacks in their goal of assimilation into French society.

Marcel considered himself Catholic, but he never denied his lineage. Montesquiou, who had made denigrating remarks about Jews in a group that included Proust, received a letter explaining why Marcel had said nothing: “Dear Sir, Yesterday I did not answer the question you put to me about the Jews. For this very simple reason: though I am a Catholic like my father and brother, my mother is Jewish. I am sure you understand that this is reason enough for me to refrain from such discussions.” Proust went on to say that he did not share Montesquiou’s ideas about Jews, or rather, that he was “not free to have the ideas I might otherwise have on the subject.”27 Proust stated his position and his independence, but he might have been less ambiguous about the ethical implications of racist remarks. Like many others, he failed to see the real dangers of intolerance, dangers that became more evident over the next several years as the Dreyfus Affair became a national obsession.

Marcel and Reynaldo had not settled into a new modus vivendi since the turbulence caused by Marcel’s infatuation with Lucien. Their efforts to find a balance appeared in their negotiations and in Hahn’s intermittent attempts to be generous and understanding. On May 21 Hahn wrote a letter reproaching Marcel for the excessive attention he paid Lucien. He informed Marcel that he would be free later in the day, but urged him not to pass up an evening with Lucien solely for his sake. Reynaldo even apologized for having scolded Marcel, observing that “life is so short and so boring” that Marcel was right not to forgo “those things (even the most trivial) that amuse or give pleasure, when they are blameless or harmless— thus, forgive me, dear little Marcel. I am sometimes quite unbearable; I’m aware of it. But we’re all so imperfect. A thousand tendernesses, Reynaldo.”28 Marcel, perhaps less in love with Lucien than he thought, could not bring himself to break with Reynaldo. He soon attempted to assert in an absurd way more control over Hahn.

Marcel spent the last Tuesday in May with Lucien reading Les Hortensias bleus, Montesquiou’s latest volume of poetry, with a preface by José-Maria de Heredia.29 While impatiently awaiting the publication of his own book, Marcel congratulated several friends who had cause to celebrate. He wired congratulations to Robert de Flers, whose recent book Vers l’orient had received an award from the Académie française. That evening Marcel went to Mme Lemaire’s soirée for the première of Reynaldo’s Breton choral work Là-bas, begun when they were so happy at Beg-Meil. Hahn’s composition was sung with great success, according to the next day’s Le Gaulois. Among the many guests who had come to hear Hahn’s music were Anatole France, Montesquiou, the Strauses, and Minister of Finance Raymond Poincaré.

On June 9 Le Gaulois and Le Figaro carried on their front pages France’s preface to Pleasures and Days and announced the book’s publication for Saturday, June 12.30 In the preface France recognized Proust’s “marvelous sense of observation, a flexible, penetrating and truly subtle intelligence,” and he spoke of the book’s “hothouse atmosphere,” where the reader is kept “among the sophisticated orchids.” Although Proust was young, France insisted that the author was “not in the least innocent. But he is so sincere, so real that he becomes ingenuous, and is charming. . . . There is something of a depraved Bernardin de Saint-Pierre in him, of a guileless Petronius.”

To oppose Petronius’s urbane debauchery, France had chosen the eighteenth-century writer Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, author of Paul et Virginie, a tale of two children brought up in poverty and innocence far from society’s corrupting influence. By calling Bernardin depraved and Petronius innocent to indicate the bipolar nature of Proust’s characters in Pleasures and Days, France must have had in mind stories like “Violante ou la mondanité” and “La Confession d’une jeune fille,” in which innocence becomes depraved, and “La Fin de la jalousie,” in which depravity is redeemed and made innocent. France ended by saying how lucky for the book that it could “go through the city all decked and scented with the flowers Madeleine Lemaire has strewn through its pages with that divine hand which dispenses roses still wet with dew.”

Friends and reviewers who noted France’s preface, Hahn’s music, and Lemaire’s drawings wondered whether Pleasures and Days was a book or a social event. Gossipers, including Fernand Gregh, soon spread the word that Mme Arman had written the preface and that France had merely signed it. According to Gregh, Mme Arman had confided to him that France, “the God of our youth,” had only added a few words here and there—such as the concluding tribute to Lemaire’s flowers—to make it more “Francienne.”31

Is this story true? Perhaps, but there are good reasons to believe that France did write the preface. In her memoirs, Jeanne Pouquet recalled that Mme Arman obtained the preface from France, as she did prefaces for Charles Maurras and other protégés, because she thought that France’s fame obliged him to help his young friends make their literary debuts.32 The text seems to bear Anatole France’s ironic tone.33 France’s secretary Jean-Jacques Brousson claimed in his memoirs that Mme Arman wrote it because “Anatole France protested against having to provide a preface for a book by an author who wrote ‘endless sentences that leave you breathless’ and that ‘roam about aimlessly.’”34 But “endless sentences,” and a discursive style, charges later leveled against Proust by some critics of the Search, do not characterize Pleasures and Days, whose sentences have a classical simplicity unlike Proust’s mature manner. The testimonies of Gregh and Brousson notwith-standing, the evidence does not support their claims.35

Marcel had finally been baptized at the font of authorship, but the experience fell short of his expectations. While nervously awaiting the first reviews, he busied himself dispatching signed copies of the hefty, deluxe volume to friends. Some, like Pierre Loti, who sent Proust a polite thank-you note, did not even bother to cut the pages. Of the fifty grand luxe copies, twenty contained an original watercolor by Madeleine Lemaire. Montesquiou received the deluxe copy no. 1, printed on Japanese vellum. In autographing Pierre Lavallée’s copy—one of the thirty copies printed on rice paper—Proust referred to his work in progress: “I say my book as though I were never to write another. You know well enough that is not true.”36

In addition to the deluxe copies, nearly 1,500 unbound copies were waiting for booksellers’ orders to arrive. With a selling price of 13 francs, 50 centimes, nearly four times the normal price for a book, there were precious few customers. Proust gave away many copies, but after a while, even he hesitated to purchase copies at author’s price. Proust soon understood that the cost of the book was killing sales. Despite his entreaties, Calmann-Lévy refused to publish an affordable edition until the expensive one sold out.

The first review appeared on June 26, 1896, in La Liberté, raising Proust’s hopes for the book’s success. In a lengthy, laudatory article, Paul Perret noted the melancholy nature and dangerous desires harbored by certain characters in the “short, fine, and often cruel stories.”37 He said that the author was a “true modern because he conveys the present soul state, the profound ennui in daily life, with a touch of decadence.” Pleasures and Days offered a variety of pieces on a small scale: “short stories, very psychological in nature, fairly bold, always interesting, descriptions and landscapes, poems, even music.” He remarked in passing that the illustrator was much better at rendering the faces of flowers than those of humans. Perret admired the poetical expression of the psychological insights, citing, for example, the sentence “Desire makes all things flourish, possession withers them; it is better to dream one’s life than to live it, although in living life one dreams it still.”38 Perret even thought that the book might act as a social “force” because “Marcel Proust is also a fine satirist.” This critic, who did not know the author, had seen what Marcel’s friends could not. There was more to Proust than a social sycophant, and his book marked a promising debut: “This young man, richly endowed, has put in his first work all he has seen, felt, thought, and observed. Pleasures and Days thus becomes the literary mirror of a soul and mind.”

Édouard Rod’s review, in the June 27 issue of Le Gaulois, basically seconded France’s “marvelous” preface and saw in Proust a budding moralist in the tradition of La Bruyère.39 Sensing the critic’s reservations, Proust thanked Rod for the review and urged him, if ever he had a free moment, “to read the first story in my book (’The death of Baldassare Silvande’), which you may not find too displeasing.”40

On July 1 Léon Blum, whom Proust had treated so unkindly when he wrote for Le Banquet, published a short, judicious review in the Revue blanche, in which he praised Proust for having “combined all the genres and all their charms.”41 After hailing Proust’s talents, Blum addressed him “affectionately” and with some “severity,” saying that the author possessed such facility of style and intellectual powers that he must be careful not to squander these gifts. Blum suggested that perhaps this debut had been too fortunate and too easy: “And I await with great impatience and confidence his next book.” Proust awaited his next production with equal impatience, but with less assuredness than Blum. He did not lack the determination to write—it was what he lived for—but he felt at sea on the makeshift raft of Jean Santeuil’s assorted planks.

On the same day that Blum’s encouraging review appeared, another, ridiculing Montesquiou, Proust, and their distinguished prefacers, came out in Le Journal. Jean Lorrain, a scurrilous figure who wrote poetry and novels in the decadent vein, bedeviled many of Paris’s elite with his weekly newspaper column “Pall-Mall Semaine.” That day’s short piece excoriated the two members of the Académie française, France and Heredia, for having set a dangerous precedent. Lorrain blamed them for encouraging such dilettantes as Proust and Montesquiou by penning “obliging prefaces for pretty society boys who desperately want to become writers and shine in the salons.”42 Although Montesquiou was hardly a boy, Lorrain lumped him together with all his minions. Lorrain decried the folly of France and Heredia for certifying such works as Les Hortensias bleus by Montesquiou and Pleasures and Days, because such recognition “turned the head of all the little Montesquitoes—the lesser or greater poets who frequent Mme Lemaire’s.” Mocking the count and his friends, Lorrain referred to Heredia as “Herediou” and Mme Arman as “Mme Arman de Caillavou,” blaming her salon for having offered Parisians this “substitute” for Montesquiou, “until now alone of his kind—the young and charming Marcel Proust. Pooh and Boo!”43 Lorrain did not address the literary qualities of Les Hortensias bleus or Pleasures and Days but contented himself, for now, with attacking what he saw as their pretentiousness.

Jean Lorrain, at forty-two, in many ways resembled a grotesque caricature of Montesquiou. Completely lacking in refinement, he was a homosexual, but one who preferred rough trade. His vulgar attacks on prominent figures had earned him thrashings and banishment from more than one salon, but such retribution did not stop Lorrain from taking cheap shots at society figures whom he envied— and Montesquiou topped his list. Proust apparently thought it best to disregard Lorrain’s attack, which, while regrettable, contained nothing that assailed his honor. He would leave it to Montesquiou, his elder, to respond. Montesquiou, who had for some time been the butt of Lorrain’s jibes, also let the matter pass, indicating that Lorrain was so far beneath his contempt as to be invisible.

In mid-July, Fernand Gregh wrote a brief, mean-spirited, equivocal review of Pleasures and Days for the Revue de Paris, in which he did not even mention Proust’s writings. Instead, he blamed the unnamed author for having assembled around him too many fairy godmothers and fathers: “Each fairy had brought his own particular grace: melancholy, irony, and a particular melody. And all have guaranteed success.”44 Here Gregh was far off the mark; Pleasures and Days was to know no measure of success. He later revised his opinion, after Proust had achieved fame, and said that the total failure of Pleasures and Days was due to its oversized format, exorbitant price, and luxurious presentation. Although Gregh later praised certain aspects of the book, such as its fine psychological analyses, he deplored the overly precious, exquisite feelings that too often showed “Proust’s first manner, when he acts like a child, sucking his finger, because he could be like that. But what did he not embody? His complexity exhausts analysis.”45 But Gregh admitted that those passages in which Proust mocks high society should have made his friends prick up their ears. Proust’s first book, Gregh maintained, had given few clues about where he was headed, and his friends missed them.46 Marcel’s friends recognized his intelligence, his talent, and his remarkable ability with words, but they were convinced that he was squandering his gifts in the glitter and chic of salon life.

Although one could argue that Pleasures and Days was a critical success, especially for a first book, it was a publishing and public relations fiasco. This volume, although unpurchased and unread, along with Jacques-Émile Blanche’s portrait of Marcel as the young aesthete dandy, cemented in the minds of many the image of Proust as a social dilettante, not to be taken seriously. Le Gaulois’s introductory paragraph to France’s preface had used two adjectives to describe Marcel’s talent that haunted him in the future: délicat et fin. Delicate and fine: two words that suggested the feelings of a precious aesthete, someone whose favorite adjective might be exquisite, someone who might be a decadent Narcissus rather than an original creative force.

Marcel, Reynaldo, and Pierre Lavallée spent a June afternoon in the Jardin des Plantes, where they were enthralled by the spectacle of transpierced doves, which bear on their breasts a red spot resembling blood. Reynaldo noted in his journal that the doves resembled nymphs who, having killed themselves over love, had been changed by a god into birds.47 The image of mythological birds martyred for love appealed to Proust, and years later, when seeking a chapter title for his novel, he considered “Les Colombes poignardées.”

Later that month, Hahn accompanied Sarah Bernhardt and her troupe to London. Hahn had already begun taking notes in his journal for the biography he would write many years later of the actress whom he and legions adored. On June 20, just after his return, Reynaldo and Marcel faced a crisis. Feeling that Hahn was slipping away from him, Marcel proposed a pact according to which each promised to tell the other everything about himself, especially about any sexual encounters, past, present, and future. Reynaldo, out of weariness or a desire to placate Marcel, agreed to the absurd proposal and swore to uphold it. Marcel had become, in many ways, the obsessed lover he had depicted in “La Fin de la jalousie.” An unpublished text from this period reveals his anguish. One is not, he observed, jealous of the happiness of the person one loves but of the pleasure she gives or the pleasure she takes. There are no remedies: “Intelligence is disarmed when faced with jealousy as with sickness and with death.”48 The preposterous pact and Marcel’s fragile physical and emotional condition were to aggravate the misunderstandings between the two men.

The Proust family had not fully recovered from Uncle Louis’s death when Nathé Weil fell ill on June 28. Two days later he died at the age of eighty-two; like his brother, Louis, he had not lingered in illness. Jeanne was so sick with grief that Marcel wondered whether she could go on living. Reynaldo, who was in Hamburg, became concerned about Marcel’s morale after the double bereavement and offered to return to Paris and comfort his friend. Marcel declined the offer because he thought the sacrifice would be too great and not really necessary: “I assure you that if the rare moments when I am tempted to jump on the train so as to see you straight away became intolerably frequent, I would ask you to let me join you, or beg you to come back. But this is quite unlikely.” He did ask Reynaldo for reassurance that he remained faithful, using the word mosch, apparently a code word in their private language for homosexual: “Just tell me from time to time in your letters no mosch, have seen no mosch, because, even though you imply as much, I’d be happier if you’d say it now and then.” He looked forward to Reynaldo’s return when his journey was done and declared that he would be “very very happy when I’m able to embrace you, you whom along with Mama I love best in all the world.”49

Proust used the remainder of the letter to tell Reynaldo what he had heard about Comte Boni de Castellane’s fête in the Bois, one of the most spectacular of the Belle Époque. Boni’s lavish party had been made possible by his marriage to the American railway heiress Anna Gould. For the occasion, eighty thousand Venetian lanterns had been hung in the Bois, whose many fountains were illuminated, and twenty-five swans had been released into the lakes. Proust was amused at the imprecise nature of the sumptuous event: it seemed to have been all things to all people. A delighted Mme Lemaire had compared it to the golden age of Versailles, “pure Louis XIV, you know,” whereas Mme de Framboise had told him, “You’d have thought you were living in Athens.” Arthur Meyer, on the other hand, wrote in Le Gaulois, “One felt one was living in the days of Lohengrin.” Marcel gleefully pointed out to Reynaldo the hypocrisy of high society in attending the unprecedented event when one of its most prominent members, Louis-Charles-Philippe-Raphaël, duc de Nemours, had died on June 26 at the age of eighty-two. “You know there were 3,000 people at that fête. Le Figaro adds solemnly: ‘All of Parisian society was there. We shall give no names. For though the whole of society was there, it was there incognito, because of the death of Monseigneur the Duc de Nemours.’ Seeing that no masks were worn, I can’t help wondering what their incognito consisted of. It’s a good dodge for going out when in mourning.”50

Marcel also discussed his vacation plans with Reynaldo, in hopes that they could spend some time together. He might soon go to Versailles with his mother, and in August to the seashore with her for a month or more. Or if Reynaldo preferred they could all go to Bex or another Swiss resort. Then he admitted that his mother wanted only to “spend a month with me, she wants me to ‘have a good time’ for the rest of the season.”51 Proust’s parents were developing a strategy to make him more independent; one of its main elements called for him to spend more time on his own away from his mother.

In early July, Jeanne and Adrien retreated to the countryside near Passy to spend a quiet few days together. Marcel wrote to her in a black mood; the recent loss of his grandfather had finally struck him, making the mortality of his parents seem more real. Adrien, while not thinking seriously of retiring, had, at age sixty-two, reduced his activities somewhat. He would leave some of the more arduous inspection tours to younger colleagues and spend more time at home with his wife and his elder son, whom he loved dearly, though he did not understand him.52

Marcel began to show the strain of recent events as summer progressed, always the most difficult season for his respiratory system. His health suddenly worsened and he became depressed. He seldom felt good or rested, and his asthma and hay fever lingered. He began smoking medicated Espic cigarettes and, assisted by his mother and servants, burning Legras antiasthma powders to relieve his respiratory conditions. He also urged his mother, in the highly unlikely event that she encountered Montesquiou or Yturri, to tell them that because the family was in mourning, she “absolutely” did not want him to attend the ceremony at Douai dedicating the monument to poet Marceline Desbordes-Valmore. He then spoke of his sadness at not seeing her: “And yet, to what purpose? When one sees, as we saw the other day, how everything ends, why grieve over sorrows or dedicate oneself to causes of which nothing will remain. Only the fatalism of the Moslems seems to make sense.”53 Marcel’s melancholy, pessimistic attitude lingered.

On July 16 a prominent figure of Marcel’s grandparents’ generation passed away. Edmond de Goncourt died of pneumonia in the Daudets’ country home at Champrosay. Proust wrote immediately to express his sorrow to Lucien, knowing how attached he had been to the elderly writer whom the Daudets considered a member of the family. Marcel, who had been thinking a lot about death, found it “beautiful” that Goncourt had died “surrounded by all of you. And so gently! For when it comes to death, sudden is gentle.” When his time came, he intended to face the end squarely: “I. . . want to know it when I die, if I am not too ill.”54

Edmond bequeathed his estate to found a literary society of ten writers that in 1902 became the Académie Goncourt. According to the terms of the will, the members were to meet monthly over dinner at a restaurant. Alphonse Daudet was among the founding members and its first president, though the society did not function officially until 1903, when it awarded its first prize. The Prix Goncourt quickly became France’s most prestigious literary prize, given annually to the best imaginative prose work.

Contrary to the title of Marcel’s book, the days of 1896 brought few pleasures. The summer was a season of grieving and remembering, particularly for Marcel’s mother, who sent him a photograph of his grandfather that he found a very good likeness. But more than the family’s losses, Marcel’s health and phobias tormented him; he was losing confidence and hope. Nothing seemed right. At two in the morning on July 16, Marcel wrote a rambling note to his mother telling her that he had left his iodine at Mme Arman’s and asking whether she could think of anything to do about it. He expressed his displeasure that the Revue blanche had published the day before the article he had sent six months ago decrying obscurity in poetry, without informing him or sending him proofs. He had supposed that they had thrown his piece in the waste bin.55 He feared his mother’s disapproval that an article by him had appeared, even without his knowledge, during a period of mourning. He mentioned an appointment at Calmann-Lévy, where he hoped to interest the publisher in the novel he was writing, and another with Dr. Brissaud, an authority on asthma, that would prevent his visiting Reynaldo at Saint-Cloud.56

In the course of his career Dr. Proust, who held the Chair of Hygiene (public health) in the School of Medicine, edited seventeen volumes of medical manuals that offered practical advice on various conditions. The message in all of these manuals, such as How to Live with Your Diabetes, How to Live with Your High Blood Pressure, and so on, was “practice good hygiene and you will live a long and healthy life.”57

In 1896 Dr. Proust asked Professor Édouard Brissaud, a distinguished director at the Hôpital Saint-Antoine, to write the book on asthma for this medical series. In his text, How to Live with Your Asthma, the learned professor concluded that the condition resulted from a “pure neurosis.” Marcel frequently consulted Brissaud’s book and may have initially blamed himself for his malady. Brissaud noted that although one does not necessarily die from a disease caused by a neurosis, there is no cure and no treatment. Proust may have ultimately rejected the doctor’s thesis about asthma; he later described Brissaud as handsome, charming, vastly intelligent, and “a bad doctor.”58 But the overall effect of Brissaud’s book, now considered to be a compendium of errors, was negative, for Proust later used its conclusions as an excuse to experiment with self-medication and to refuse treatments in clinics that might have provided lasting benefits.

Adrien and a colleague, Dr. Gilbert Ballet, were writing another book, to be published in October 1897, for their series. L’Hygiène du neurasthénique (How to live with your neurasthenia) prescribed treatment for this newly named disorder, which primarily afflicted members of the upper classes, those who supposedly used their brains more than their muscles. This manual read like a case study of Marcel. Among the debilitating symptoms of neurasthenia were dyspepsia, insomnia, hypochondria, asthma, hay fever, and abusive masturbation. Of particular interest, considering Adrien’s experience in raising his elder son, are the pages on the dangers that high society posed for such patients. Parisian high life, with its endless series of visits, dinners, balls, soirées, and other obligations, easily led to dangerous excesses: for example, fatigue resulting from meals that were too long and too heavy; staying up late and losing sleep, or sleeping at irregular hours. Who could be surprised, the authors asked, if such a regimen often produced psychosomatic asthma?59

Dr. Proust apparently remained convinced that there was nothing physically wrong with Marcel.60 In the manual Proust and Ballet pointed out that neurasthenia often developed in those who pursue vain pleasures rather than selecting a career suitable to their milieu and abilities.61 Furthermore, neurasthenic patients are highly suggestible and prone to phobias, such as the fear of drafts, germs, or noise.62 Marcel had already developed the first and last of these phobias and did not neglect to acquire the one related to germs. The example of patients who suffer from auditory hypersensitivity can be seen as prophetic of Proust’s later retreats to his famous cork-lined room: In order to “escape noise, such patients shut themselves up in their rooms and live in veritable reclusion.”63 Jeanne and Adrien had already seen the endless housekeeping complications that arose when a grown, unemployed son needed to sleep all day, when noises indoors and out increased a thousandfold.

There was more. Abulia, or the loss of willpower, was described as another debilitating trait of the neurasthenic. Marcel exhibited this symptom in his endless hesitations about career choices and vacation plans. Nothing, observed the hygienists, is more painful to such patients than making a decision.64 Had Marcel not already lived the experience, he could have taken the chief motivation for his protagonist right out of his father’s book. The Narrator’s quest is largely a lifelong attempt to regain his will, lost as a child in the scene of the good-night kiss. From that moment on, until he regains his will on the verge of old age, he considers himself certified as suffering from abulia, which constitutes the greatest obstacle the Narrator must surmount in his quest to become a creative person: Lack of will, he observes, is “that greatest of all vices,” for it makes resisting the others impossible.65

A recommended treatment for patients such as Marcel was to isolate them from family and familiar surroundings. If the overwrought patient left his family and the milieu in which his neurasthenia originated to vacation in a calm, pleasant spot in the countryside or at a sanatorium, he would quickly regain his mental equilibrium; new images would occupy his mind and his hypochondriacal preoccupations would begin to disappear.66 Proust’s parents were planning such a treatment, without telling Marcel why, for his next vacation.

Soon after Reynaldo’s return from Hamburg, a quarrel erupted with Proust that made Hahn threaten to break their pact of fidelity and confession. The rift had apparently started when Marcel tried to guess the name of the person to whom Reynaldo was attracted and whom he refused to discuss. Marcel protested furiously Hahn’s refusal to divulge the name and tell all, saying that his silence, if maintained, would be a breach of his oath: “That you should tell me everything has been my hope, my consolation, my mainstay, my life since the 20th of June.” Marcel admitted that the oath he had forced on Reynaldo was cruel but accused him of even greater cruelty and implored him to keep his promise: “If my fantasies are absurd, they are the fantasies of a sick man, and for that reason should not be crossed. Threatening to finish off a sick man because his mania is exasperating is the height of cruelty.” Marcel closed by saying that he often deserved reproaches himself and by asking Reynaldo to be indulgent to his pony.67 His lucidity in recognizing the nature of his mania and his frankness in admitting it were, as it turned out, positive signs. But first, there would be more difficult moments to endure.

Not long afterward, Marcel wrote Hahn another letter filled with recriminations, acknowledging that their friendship had considerably diminished; he cited among his grievances Hahn’s refusal to accompany him home after a soirée at Madeleine’s, preferring instead to remain for supper.68 He repeated Hahn’s warning, made earlier in the evening, that one day Marcel would regret having made him promise to tell all. Marcel declared that he had attempted to remain faithful to Reynaldo in order to avoid painful confessions: “Wretch, you don’t understand, then, my daily and nightly struggles where the only thing that holds me back is the thought of hurting you.” Then he observed, “Just as I love you much less now, you no longer love me at all, and that my dear little Reynaldo I cannot hold against you.” He signed the letter, “Your little pony, who after all this bucking, returns alone to the stable where you once loved to say you were the master.” Marcel recognized that the love affair was over, but fortunately not their mutual affection and the joy they took in each other’s company.

Proust seized an opportunity to publicize his book when Charles Maurras asked him for a photograph to run with the review he was writing of Pleasures and Days for the Revue encyclopédique. Eager to look his best for his first published photograph, Proust decided to have new pictures made by the distinguished photographer Otto, who immortalized prominent Parisians and whose studio was conveniently located in the place de la Madeleine, only a few steps from Proust’s apartment. By late July, Proust had sent the photograph for the brief but highly prescient review that was to appear on August 22. Maurras saw in Proust a new moralist who “shows such a wide variety of talents that one is bewildered at having to register them all in so young a writer.”69 He praised Proust’s style for its “pure, transparent” language and hailed him as a writer around whom the new generation could gather.70 A new author could hardly have wished for a better review, but as gratifying as it was, Maurras’s words of praise did not increase sales.

On August 8, in hopes of improving his health, Marcel and his mother boarded a train at the Gare de Lyon for Mont-Dore, a spa in the mountains of central France that was noted for its treatment of asthma. From Mont-Dore a more composed Marcel wrote Reynaldo and, repentant, proposed that their pact be annulled: “Forgive me if I’ve hurt you, and in the future don’t tell me anything since it upsets you. You will never find a more affectionate, more understanding (alas!) and less humiliating confessor. . . . Forgive me for having added, out of egoism as you say, to the sorrows of your life.” Marcel proclaimed again his love for Reynaldo: “I have no sorrows, only an enormous tenderness for my boy, whom I think of, as I said of my nurse when I was little, not only with all my heart, but with all me.” At the end of the letter Marcel declared himself cured of jealousy.71 His obsessive preoccupation with Reynaldo established a pattern of behavior that he was to dissect and analyze with brutal lucidity in the principal pairs of lovers in the Search: Swann and Odette, the Narrator and Albertine, and Charlus and Morel.

If the calm atmosphere of Mont-Dore enabled Marcel to resolve the emotional conflict with Reynaldo, it brought no relief to his asthma. He and his mother had at first blamed the spa for his failure to improve, then realized that the real source of his trouble came from the farmers of the Auvergne, who were busy making hay, thus saturating the air with allergens. During his stay he read Dumas’s La Dame de Monsoreau and, at a somewhat slower pace, Rousseau’s Confessions; he also worked intermittently on the drafts of Jean Santeuil.

Marcel wrote an apologetic letter to Lucien, worrying that his exemption from this year’s reserve training would not be approved and that he would have to report for duty at Versailles on August 31. Trying to resolve this problem before leaving Paris had prevented him from saying good-bye to his “dear little one. I think of you so often that it’s unbelievable.” He told Lucien that he was so unhappy with his lack of progress at Mont-Dore that if his condition did not improve soon, he would take the train to Paris. Did Lucien, he wondered, still harbor some feelings of friendship for him? Or had he completely forgotten him? He invited Lucien to come over and select one of the photographs from Otto, promising many “ridiculous poses from which to choose.” Although he signed the letter “Your little Marcel,” his relationship with Lucien had cooled from love to friendship.72

In late August, Marcel and his mother returned to Paris. Soon his parents left, as usual, on their separate ways for vacation, Jeanne to the Hôtel Royal in Dieppe, Adrien to his favorite watering spot in Vichy. Marcel would remain in Paris until he decided where to spend the fall vacation, a choice that would be largely determined by his health. Before leaving for the coast, Jeanne, having decided their apartment needed a face-lift, made arrangements for painters to come and for new carpet to be laid while she and Adrien were away. On September 2 Marcel, waiting in bed at 9:30 for Félicie to bring his breakfast tray and the morning paper, wrote his daily letter to his mother. He was obviously pleased with himself for having returned home the evening before at eleven, but he had not gone to bed immediately because his chest “felt rather oppressed,” despite his having smoked several Espic cigarettes during the day. He decided that he should burn some of his antiasthma powders, whose smoke he inhaled seeking to relieve his bronchial tubes. Because this was the first time he carried out what he called a “fumigation,” the procedure “took ages.” Once in bed, his chest continued to feel tight, and he arose to take two capsules of amyl. He fell asleep quickly, although he woke at 5:30 A.M., panting severely. He got out of bed and burned a mound of Escouflaire and Legras powders. This habit of fumigating was to become an enduring ritual.

Marcel wrote his mother again on Sunday, September 6, with a request. He needed to know where he should send the copies of Pleasures and Days he intended to give Robert de Flers, on vacation, and Robert de Billy, now posted to the French embassy in London.73 Would she write and find out their addresses and do the same for Laure Hayman, also vacationing? He was making an effort, he told her, though he admitted he was “a bit of a grumbler,” to show her that she need not worry. Having pressed his mother into service as his remote secretary, he then urged her, “Go for walks, bathe, don’t think too much, don’t tire yourself by making your letters to me too long, and let me thank you once more for the tranquillity of these last few weeks, which you made me spend so happily.”74 He hoped she would report that the wind was blowing hard on the coast, for she believed high winds were good for her health. To reassure her of his equilibrium and good intentions, he told her that he was going “to work a bit on a little episode” for his novel. He congratulated himself for having written at least one “breezy” letter in which he had complained about nothing and expressed concern for her happiness and well-being. He considered it a tour de force.

The remaining September letters to his mother chronicle his constant difficulty breathing and sleeping and his mostly successful attempts to avoid resorting to soporifics. He asked the lending library for the Correspondence of Schiller and Goethe and Par les champs et par les grèves (Across fields and shores), Flaubert’s book on Brittany, another indication that he was working on Jean Santeuil. He admitted his discouragement at not having found the story line, at not being able to conceive it as a whole. But he had filled one notebook of “110 large pages,” a quantity he underscored in the letter to his mother. As he continued to fill pages and accumulate copy, he wondered where he was headed. Before he began working on Jean Santeuil, he had written short stories, sketches, essays, and poems. Proust was finding that the novel was not for him an instinctive genre.

Robert, interning at Necker Hospital, visited Marcel on September 16. The two brothers discussed the pros and cons of Robert’s spending the night at home, but he decided to return and sleep at the hospital. Robert accompanied Marcel as far as Mme de Brantes’s town house, where a soirée was in progress. There the brothers parted, Robert to tend to his patients, Marcel to amuse the party goers. Proust always said the night air was easier to breathe.

His health problems, however, whether real or psychosomatic, made him profoundly unhappy. His letters flowed from Paris to his mother in Dieppe, detailing his ailments and his increasing reliance on drugs to alleviate his symptoms, news that alarmed Mme Proust, who feared the habit-forming dangers of drugs containing narcotics. Marcel blamed the need for a sleeping potion on the disturbance caused by the painters she had hired: “I must confess to you, I was woken up so early by the painters that I had to take a cachet of Trional (.8 of a grain), as I couldn’t go on sleeping so little. And I was going to ask your permission to flee to Dieppe to escape the painters. But what you say of the noise there has put a spoke in that wheel.”75 Two days later Marcel confessed again with regret, knowing his mother would be upset, that he had taken amyl in the evening and Trional in the morning. But now he would have to contend with the carpet layers, who planned to begin work at 9:15, when he would still be in bed. Greatly annoyed by this arrangement, he urged his mother to write to the workmen and insist on a different schedule.

After more admonitions from Jeanne, he wrote, “I am continuing to abstain rigorously from Trional, amyl and valerian.” Sensing the need to reassure her about his condition, he wrote that he had been to dinner with a friend in the Bois de Boulogne and had “felt well ever since, which hasn’t happened for ages.” He had resumed work on his novel and vowed not to miss another day in order to have his manuscript ready for submission by February, but he lacked confidence in his ability to produce a worthy novel. He felt certain that the result would be detestable. In a postscript he urged Jeanne to remain in Dieppe, where she could continue to recuperate “for me, when it would do me so much good, until October 15? Papa would be much freer here without you during the celebrations for the Czar’s visit.”76

Paris was preparing for a state visit by Czar Nicholas II of Russia, October 6–8. President Faure and Nicolas II would lay the cornerstone for what would become the city’s most elegant bridge, the Pont Alexandre III, to commemorate the alliance between France and Russia dating from 1892. As a leading international health authority who had visited Russia, as well as a close friend of the president’s, Dr. Proust would be invited to many of the events surrounding the czar’s visit.

Jeanne, despite her son’s entreaties, did not wish to remain in Dieppe and by September 24 had moved nineteen miles up the coast to Le Tréport, where she resumed her bathing treatments in the sea. Jeanne told Marcel about a new luxury she was enjoying. The spa had the same sort of writing tables as at home, except that at Le Tréport they were illuminated by electric lighting. She was finding the treatment beneficial and had already begun to sleep much better. Another modern innovation at which she marveled was the excellent mail service, which made her correspondence with Marcel resemble a “conversation.” A letter he had mailed at a quarter past noon was handed to her four hours and fifteen minutes later. She had heeded his pleas about the carpet layers and asked their manservant Jean to arrange for the workers to come after lunch, if possible, and if not, after 10 A.M. If necessary, the men could make two trips to finish the job. The family had begun making concessions to Marcel’s schedule, which continued to shift toward a more nocturnal existence.77

Jeanne informed Marcel that she planned to stay in Le Tréport until October or until the baths began to wear on her. She wanted him to spend his vacation away from her and urged him to try Saint-Cloud, where she knew he would find Reynaldo. If Jeanne believed that her grieving depressed him, she was mistaken. He would have been only too happy to console her and distract her and be comforted in turn by her presence and love. His parents’ insistence on his having “a good time” later in the fall was to have unfortunate results. Jeanne and Adrien were desperate for measures that would pull Marcel back from the life of an invalid, a state into which he seemed to be declining for reasons they believed were primarily neurotic.

Marcel finally narrowed his autumn vacation choices to Segrez and Fontainebleau, whose forest was said to be splendid in the fall. Around mid-October he wrote to Jean Lazard, a friend who lived in Fontainebleau, to inquire about conditions and requested an answer by return mail. Such a prompt reply might have appeared reasonable to Marcel, but his correspondent must have been taken aback by all the questions asked in the letter. Marcel required a room or two located in a salubrious spot—but not by the river—in a quiet lodging with no noisy neighbors in the adjoining room; he also wanted to know the cost if he should decide to take a small apartment.

Marcel found it more and more impossible to make decisions about travel destinations and departure times and so hesitated until the last possible minute to choose between Fontainebleau and Segrez. When he finally left for Fontainebleau on October 19, his departure was so hasty that he forgot to pack a number of items. Upon arriving at his destination, the Hôtel de France et d’Angleterre, he immediately felt homesick and miserable. Nonetheless, he wrote asking his mother to send the forgotten items. Marcel’s choice of Fontainebleau may also have been influenced by Léon Daudet’s decision to retreat to that town in order to finish his fifth novel Suzanne, to be published in November. Marcel must have envied his friend’s productivity.

When Marcel’s mother received his letter the following morning, she became alarmed and went across the street to Cerisier’s bakery, where she tried unsuccessfully to use a new means of communication: the telephone. The bakery’s telephone apparently could be used only for local calls. Electric lighting and the telephone, two wonders of late nineteenth-century technology, had begun to change the lives of millions of people. Marcel, usually so curious about technological advances, had for some reason been reluctant to use the telephone. Although the Prousts had neither a telephone nor electric lighting at home, Jeanne had urged her increasingly dependent son, who hated being away from her, to experiment with the telephone as a direct way of remaining in contact when they were separated.

Frustrated at not being able to reach Marcel, Mme Proust went home for lunch. At one o’clock, she wrote him a letter promising to send his tie pin, watch, coat, hat, and his new umbrella, which she and the servants had as yet been unable to find. After posting the letter, she tried to call him again from another station. Finally, after much waiting, the call went through. During the conversation, which seemed miraculous to Marcel, bringing his mother and her incredible sweetness so near, he told her Fontainebleau was cold, damp, and dreary and argued his case for returning home immediately. That evening Jeanne wrote for the second time that day, urging him to be patient and attempt to “acclimatize” himself. She suggested Illiers as an alternative vacation choice because he had been “wonderfully well” there in cold weather. After sending him a “thousand kisses,” she added a postscript to her “dear boy” that expressed her greatest concern: “I am waiting impatiently to hear what sort of night you have had and whether you have managed to break all ties with that insidious Trional.”78

After the phone call Marcel felt miserable from having heard his mother’s fragile, disembodied voice, confirming his suspicions about the intensity of her suffering over the loss of her parents and giving him the “first terrible inkling of what had broken forever within her.”79 He nearly panicked and rushed back to her. In spite of his distress, he summoned the discipline to write down his impressions of the exceptional communication and emotions it had provoked. He sent his mother what he wrote, more for sentimental than literary reasons, to show her how much he loved her and how wretched he was. He was no longer the independent, carefree Marcel of a year ago, who had prolonged his stay at Beg-Meil for as long as possible to remain on vacation with Reynaldo, while eagerly exploring the coast and taking notes for his novel. How much had changed in one year; he and Reynaldo had quarreled and separated; Marcel’s “dear little Lucien” had displaced but not replaced the more stable and reliable Reynaldo; his grandfather and uncle had died; Pleasures and Days had been published and gone largely unnoticed. And now his body and emotions were betraying him through sickness and neuroses, and he seemed mired down in his writing. He had never been so unhappy.

In the fictionalized account that he later included in Jean Santeuil, Proust reversed the order of events: Jean panics and then speaks to his mother on the phone.80 Proust captured for his character the struggle between the forces of habit and comforts of home and the strange, hostile environment in which he had landed. The passage abounds in images suggesting incarceration, claustrophobia, and suffocation, future themes of the Search, where so many characters become prisoners of their manias.

The day after the phone call, Marcel wrote to his mother and listed all the things that were wrong. From the moment he arrived at Fontainebleau, nothing inside or outside the hotel had pleased Proust, from the way the bed was set up in his room (“All the things I need, my coffee, my tisane, my candle, my pen, my matches etc. etc. are to the right of me, so that I keep having to lie on my bad side, etc.”) to the colors of the forest (“still all green”), the town itself (“no character”), and the terrible weather that persisted (“It’s pouring”). Still, “I had no asthma last night. And it’s only just now, after a bad sneezing fit, that I had to smoke a little.” He then told her about the terrible hours he had spent after their phone conversation, which he described as the most distressing time in his life. Later in the evening, needing someone to talk to, he had gone to the station at eleven o’clock to meet Léon Daudet, who was returning from a brief trip to Paris. Daudet had insisted on their taking their meals together, which must have sounded like good news to Jeanne.

Because his many complaints about feeling sick and miserable had failed to persuade his mother to allow him to return, he tried another way to hit a sensitive nerve: the great expense. He detailed the costs of keeping a fire burning in his room and the extra lamps required because in the off-season there was no lighted parlor, only the lights in one’s room. Surely, she could see he would do better to come home? If his parents wanted him to breathe non-Parisian air to see whether his asthma improved, he suggested sleeping at home but going out to Versailles every day to write. Finally, Marcel made one request that sounded positive: “Do ask Papa for something to stop my nervous laugh. I’m afraid of irritating Léon Daudet.” And he added a bit of good news: “No Trional.”81

Marcel’s mention of cost did not faze his mother. Although Jeanne always regarded thrift as a cardinal virtue, she felt that no expense would be too great if she could persuade her elder son to manage on his own. She was encouraged by his readiness to control his nervous laughter, a disorder he had treated so lightly but that now embarrassed him. Jeanne much preferred that he spend time with the older, mature Daudet brother, who was married and pursuing a career as a journalist, critic, and novelist. In his memoirs Léon recalled that he and Marcel spent “a charming week” together, “walking by day in the forest, chatting in the evening by the fireplace, in the deserted . . . drawing-room.”82 With his extraordinary politeness, Marcel succeeded in hiding from Daudet how tiresome he found their conversations, especially at mealtime. But Daudet did observe how extraordinarily sensitive Marcel seemed to be and likened him to someone who had been “flayed alive.”83

In Marcel’s next letter he told his mother that relocating was out of the question. Apparently, he did not intend to leave her side ever again. He told her that he had “lost his faith in country places.” And a new worry had seized hold of him: he was afraid that he would be unable to pay his hotel bill because of the charges he had run up, and to make matters worse, he had lost a lot of money through a hole in his pocket. He confirmed his determination to work, but he must first find a place where he would feel well enough to write. If writing was difficult under the present circumstances, he could at least read the books from which he expected to draw inspiration. He asked his mother to send “immediately” several of Balzac’s novels, including Le Curé de village, the Shakespeare volume with Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra, the first volume of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, and Middlemarch by George Eliot.84

Later that morning, after they had posted their letters, he and his mother spoke briefly on the telephone. Mme Proust now seemed resigned to letting him come home because of the disastrous report, but she would send the books and wait and see. The phone connection had been so bad that she couldn’t make out certain titles, but she would receive his letter with the list at seven that evening.85 Things only grew worse. In his next letter Marcel said: “I write to you in a state of deep dejection.” The missing money, he wrote, “after annoying me at first now takes on fantastic proportions.” He went so far as to say that he now understood “people who kill themselves for nothing at all.” He made an urgent request for money— “Please send me a lot too much”—because his greatest fear was being unable to purchase a train ticket if he decided to return home.

Even a visit from Lucien had, surprisingly, made matters worse. They quarreled and parted on icy terms. Marcel composed a letter to his mother telling her that he was “worn out with remorse, racked with conscience, crushed with dejection.” He would give Fontainebleau one more day. Reluctant to send such a bleak letter, he left it on the table and went to bed. The next morning at 9:30 he added a postscript: “I’ve had a good night, I’m very refreshed but also very congested.” But he told her that his reservations about Fontainebleau remained just as strong.86 Then he mailed the letter.

That morning Jeanne sent Marcel a wire and then one hundred francs, along with most of the books requested. That evening, after receiving his doleful letter, she wrote again, advising him to combat his anxieties and stop tormenting himself. He was not to be concerned about the bill. “If I knew you were flourishing over there, I would find the costs very sweet!”87

Marcel, far from flourishing, returned to Paris, having written many fewer pages in Fontainebleau than he had intended. Other than the telephone episode, which he would use with few changes in the Search, the only other text that was clearly written at Fontainebleau was an episode concerning Jean’s attempts at seducing a married woman after he became bored with his mistress.88

Once home, Marcel’s condition improved, and he resumed many of his normal activities. He and his friends were soon intrigued by the publication of the single most important piece of evidence used in the secret trial to convict Dreyfus. On November 10 Le Matin published a photograph of a secretly obtained facsimile of the bordereau, the memorandum sent by the spy in the French army to the German embassy. It listed the top secret documents detailing French weaponry and the plans for troop deployment in the event of an attack that the spy would sell to the Germans. Publication of the bordereau had an electrifying effect. Col. Georges Picquart, who had become chief of counterintelligence the year following Dreyfus’s conviction and whom the army suspected of leaking the document, was forced into exile.89 Commandant Marie-Charles-Ferdinand-Walsin Esterhazy, the real spy, became terrified that his handwriting might be identified. Although it would take years to break down the wall of secrecy and sort out the mountain of evidence that the French high command had forged against Dreyfus, the publication of the bordereau was the first major step toward an appeal and new trial.

One December evening at a party given by Reynaldo’s mother, Marcel met his friend’s twenty-year-old English cousin, Marie Nordlinger, a young artist who had come to France to continue her studies. She and Proust liked each other immediately and became friends. Marie later encouraged his interest in the English art critic John Ruskin and assisted in his translations of two of Ruskin’s works.

Marcel maintained his close ties with Laure Hayman, who by the end of the year had asked him to drop “Madame” and use her given name. He sent her a vase for her collection and, along with it, a keepsake from Uncle Louis, a tie pin she might use for one of her hats; he hoped it would appeal to her “sentiment of friendship” without offending her taste.90

In early November he wrote to Fernand Gregh, thanking him for the inscribed copy of his book of verse La Maison de l’enfance. Proust, who had not forgiven Gregh’s unkind notice for Pleasures and Days, couched his expression of gratitude for his friend’s book in such guarded and ambiguous terms that afterward he dared not send the letter. The week before Christmas, while leafing through the Revue de Paris, Proust had seen a new note Gregh had written about Pleasures and Days. In his brief second notice, Gregh again praised the preface, Hahn’s music, and Lemaire’s drawings, but this time he mentioned Proust’s text and said that it stood well on its own. In short, Gregh recommended Pleasures and Days as a “very beautiful gift book.” The Christmas shoppers paid no attention to Gregh’s advice— or if they did, they recoiled at the price.91