IN EARLY JANUARY, Marcel wrote Mme Straus that nothing had changed concerning his novel. He wanted to publish it at his own expense, but Louis de Robert had overcome Proust’s holiday resolve and convinced him that the idea was “absurd,” warning him that such a solution would ruin his reputation as a serious writer. If Proust paid to have his book published, Robert had argued, he and his work would be discredited and he would be considered one of those “idle rich” who publish their “literary elucubrations” out of vanity. Proust was “too great an artist” to abandon hope of finding a publisher who would recognize his worth, treat him as a professional, and pay him royalties.1 Proust had received Robert’s assurance that “he could easily find me a publisher. I’m waiting to see.”2

Marcel agreed to Louis’s plan of submitting the manuscript to Alfred Hum-blot, general editor at Ollendorff. Humblot had a very high opinion of Robert’s writing and had recently approached him about the possibility of publishing his next work. Surely an enthusiastic recommendation by Robert would guarantee an appropriate appraisal of Proust’s manuscript. In early January, Marcel wrote Robert that he was sending the “manuscript to M. Humblot with a letter . . . and without offering to pay the costs of publishing since you don’t want me to do that either. Since it’s you who’ve done everything, the least I can do is not disobey you.” Yet in the postscript Proust stated his intention to do just that: he would tell Humblot that he “was prepared to subsidize publishing as amply as he considered suitable.”3

To thank Robert for his efforts and kindness, Proust gave his friend a ring monogrammed with the initials LR. Proust was enchanted when Robert accepted the ring and agreed to wear it, but he suggested, because people often misrepresent “friendship between men as soon as it becomes somewhat affectionate,” that Louis not say who had given him the ring. “If you want to, you certainly may, naturally it’s up to you.”4

On January 14 Proust went to the Figaro with Calmette’s New Year’s gift, a black moiré cigarette case with a monogram in brilliants that Proust had had made for the editor at Tiffany’s. He described the present to Mme Straus: “extremely simple, very pretty, and costs a little less than 400 francs.”5 When Marcel stopped by Calmette’s office and placed the wrapped package next to him at his desk, Gaston did not look up or speak, but merely shrugged his shoulders “with an affectionate air.”6 Proust invited Calmette to open the present, but he only gazed at it “in a vague way.” The busy editor, preoccupied by the forthcoming presidential elections, only commented: “I really hope Poincaré will be elected.”7 He then walked with Marcel to the door, saying “Perhaps it will be Deschanel.” While Calmette was pleasant, he did not say a word about Fasquelle, which convinced Proust that Fasquelle had never promised to publish his novel. Calmette never acknowledged the cigarette case.

While at the Figaro, Proust, eager to publicize his novel, met with Francis Chevassu regarding the “prose poems” that he hoped the editor would publish in the literary supplement. Before returning home Proust stopped by Emmanuel Bibesco’s apartment and asked him to use his influence with Copeau to publish some excerpts from Swann’s Way in the NRF’s May issue. Chevassu and Copeau both refused Proust’s texts.

In their letters, Proust and Louis de Robert compared notes about the life of an invalid. Proust admitted that the long periods of illness, when confined to his bed, had encouraged him “to develop somewhat the mentality of sick, old women,” making him distrust those who served him when he entrusted them with letters or errands of a personal nature.8 Bemoaning his sedentary existence, Marcel told Robert that for a year he had wanted to do only two things: see the exhibitions of the Manzi and Rouart collections, especially the impressionist works, and listen to Beethoven’s late quartets. It had been impossible for him to accomplish this. “In fifteen years I believe I was able to go twice to the Louvre. But fortunately, beneficent nature gave me something more valuable than health, illusion. Now, as I write to you, I am convinced that I will be able to go tomorrow to see the Sainte-Anne portal at Notre-Dame Cathedral, my present great desire.”9 Proust was to use details from the statuary at Notre-Dame for his depiction of the church at Balbec.

Proust had written to Mme Straus in mid-January about his daily attempts to leave his apartment early, visit her, and stop at Notre-Dame in front of the Saint-Anne portal, “where for the past eight centuries a human spectacle much more charming than the one we are accustomed to has been visible; but those who pass in front of it never stop or raise their eyes; they ‘have eyes but see not.’” His eyes, “perhaps, would look and love; but they don’t pass in front of it, they open only in the dark and contemplate only a cork wall.”10 Finally on the last day of January, Proust threw his “fur-lined coat over his nightshirt” and went to stand for two hours in front of the medieval portal.11 He also went to visit another wonder of medieval Gothic architecture on the Île de la Cité, the Sainte-Chapelle, whose magnificent stained-glass windows partly inspired those in the church of Combray.12

By mid-February, Proust, who continued to hope that Fasquelle would publish his collected articles and parodies, wrote to Anna de Noailles, requesting that she lend him her copies of Les Éblouissements and “On Reading.” He needed these for his proposed volume of collected writings. Proust admitted to Anna that he was somewhat discouraged by “everyone’s constant refusal to publish anything by me.”13

When Louis de Robert received Ollendorff’s devastating rejection letter, he was so horrified that he asked Humblot to send him a “banal rejection” letter that he could show to the author. Proust expressed his disappointment over Humblot’s letter, which he found “very discourteous.” He sensed that there was more to the story than Robert allowed, observing, “Here is a man to whom you’ve spoken of me as only you know how, who has just had 700 pages to consider, 700 pages in which, as you’ll see, a great deal of moral experience, thought and pain have been, not diluted but concentrated, and he dismisses it in such terms! It almost makes me wonder whether there isn’t another reason. We’ll talk about it some day.”14

Proust kept pressing Robert until he learned more about Ollendorff’s report. Ollendorff’s reviewer had written, in what became one of the most famous rejection letters ever, “My dear friend, I may be dead from the neck up, but rack my rains as I may, I fail to understand why a man needs thirty pages to describe how he tosses and turns in his bed before falling asleep.”15 Robert was so furious that he threatened to break off relations with Ollendorff and Humblot, but Proust wouldn’t permit it: “Allow me to say to you with the deepest sincerity that you would cause me real and lasting pain if you altered in any way whatsoever your friendly relations (or your professional relations) with M. Humblot. I shall be entirely frank. I find M. Humblot’s letter . . . utterly stupid.”16 But Proust admitted, “Alas, plenty of other readers will be equally severe.” Robert scolded Humblot, telling him, “Fortune has knocked at your door and passed you by.”17 Louis promised Proust not to alter his relations with Humblot; “I simply regard him as a fool,” he wrote, while predicting that Proust would “triumph in the end and taste the true glory... which you deserve as one of the first among us.”18

As soon as Proust learned of this latest rejection, he decided to follow no one’s council but his own regarding the publication of his novel. He wrote immediately to René Blum, who knew Bernard Grasset well, asking him to undertake negotiations with Grasset “to publish, at my expense with me paying for the printing and publicity, a major work (let’s call it a novel, for it is a sort of novel) which I have finished.” Proust outlined, as he had for the other publishers, the work’s content and size, saying he was very ill and needed “certainty and peace of mind.” The only way he could obtain the immediate and “clear presentation” of his work was by publishing himself. He did not offer Blum or Grasset the opportunity to appraise the manuscript. He wrote that he would like M. Grasset to be involved in the book’s success and to that end would be “grateful” if Grasset would take a percentage of the sales. Thus the publisher would have no expenses and might actually “earn a pittance.” Even if the book did not sell well initially, Proust thought that it might eventually catch on with the public. But in any event he believed that the work, “far superior to anything I’ve yet done,” would one day “bring honor” to Grasset. Before closing, Proust stressed the need for discretion when telephoning or writing and suggested that Blum and Grasset seal their letters with wax. He insisted that this book was not a collection of articles: “It is on the contrary a carefully composed whole, though so complex in structure that I’m afraid no one will notice and it will seem like a series of digressions.”19

On Sunday evening, February 23, Proust wrote a letter to Blum to thank him for his trouble. He mentioned the possibility of putting his novel up for the Prix Goncourt, if that would please Grasset. Proust admitted that he was not quite certain what the Prix Goncourt was. He mentioned the Prix Fémina-Vie Heureuse, instituted in 1904 by the Fémina and Vie Heureuse reviews, but excluded it because of the indecent nature of his work. In the postscript, as an afterthought, the novelist offered this description of the work he wanted to publish: “I don’t know whether I told you that this book is a novel. At least it’s from the novel form that it departs least. There is a person who narrates and who says T; there are a great many characters; they are ‘prepared’ in this first volume, in such a way that in the second they will do exactly the opposite of what one would have expected from the first. From the publisher’s point of view, unfortunately, the first volume is much less narrative than the second. And from the point of view of composition, it is so complex that it only becomes clear much later when all the ‘themes’ have begun to coalesce.”20

Blum, wasting no time, met over the weekend with Grasset and obtained his agreement to publish the book. When Proust woke up late Monday afternoon, Blum’s letter with this news was waiting for him. The entire process had taken four days. That evening Proust wrote to Grasset, repeating the offer of a percentage of the sales and asking Grasset to name the figure, “which could increase if the editions multiplied, but leaving me nevertheless the ownership of my work.” Proust sought to allay every conceivable hesitation Bernard Grasset might have. The author proposed a publishing schedule of October for volume one and June of the following year for the second. Although Proust was still undecided about divisions and titles, he suggested calling the first volume Time Lost, Part One, and the second volume Time Lost, Part Two, “since in reality it’s a single book. It’s as you like. The manuscript you have is Part One. The other part, the one that will appear ten months later, as yet exists only in illegible drafts.”21

Soon Proust sent another letter to Grasset, saying that his “own financial interest” was less important to him than the “infiltration of my ideas into the greatest possible number of brains susceptible of receiving them.” Proust wanted a strategy to earn a wide readership. Grasset went along with Proust’s suggestions, although he must have doubted whether such a work would attract many readers. By March 11 Proust and Grasset had settled on a contract, which was signed on March 13.22 Proust had sent his first payment of 1,750 francs to Grasset when he returned the draft agreement on March 11. All that lay between Proust and publication now was his unusual method of correcting the proofs.

On March 14 Proust related to Blum his recent exchanges with Grasset. During their negotiations Grasset had first asked Proust to price the volumes at ten francs. That way the publisher could give the author four francs per copy, while recovering his expenses. But Proust told Grasset that he did not want his “thoughts to be reserved for people who spend ten francs on a book and are generally stupider than those who buy them for three, so I insist on three fifty.” Proust refused to accept more than one franc, fifty centimes as his share of the sales, a gesture that was “noble on my part in that I have all sorts of troubles (please don’t tell him this); I hope he will have been touched.”23

During the winter and spring Proust attended a number of concerts. Always a passionate lover of music, he now concentrated on creating for his fictional composer works that inspired Swann and the Narrator to meditate on the creative imagination. This determination to capture the essence of music gave Proust reason to attend concerts more frequently, providing an enriching supplement to his evenings spent bent over the theatrophone. On February 26 Proust and Lauris attended a concert by the Capet String Quartet at the Salle Pleyel. The program included works that from this time on he would lose no opportunity to hear: two of Beethoven’s Late Quartets and the Grosse Fugue.24

Sometime in the spring of 1913, Alfred Agostinelli lost his job as a driver and appealed to Proust for work. Odilon had become Proust’s regular driver, but the writer hired Agostinelli as secretary—with some reservations about his capacities in this regard—to finish preparing the typescript of Swann’s Way. As Proust later explained to Émile Straus, “It was then that I discovered him, and he and his wife became an integral part of my life.”25 Agostinelli, whose refinement and intelligence Proust had noted on earlier occasions, had lost most of his adolescent plumpness and had become something of a daredevil. He had always been fascinated with bicycles and motorcars; now, like many daring young men of his generation, he became passionately interested in the ultimate machine of speed: the airplane.26 When Agostinelli and Anna, whom the secretary had always claimed was his wife, moved into Proust’s apartment, they disrupted to some degree his bizarre but highly organized schedule. But the biggest distraction, far greater than the practical considerations of new lodgers, was to be Proust’s emotional involvement with Agostinelli. The writer quickly became infatuated with the young man. Agostinelli, who had been the “artisan of my voyage” in 1907, became, in 1913, the “companion of my captivity.”27

Anna has been described as ugly and unpleasant. The only known photograph of her shows a rather plain woman with coarse features.28 Proust, who also found her unattractive and disagreeable, wrote that she was insanely jealous and would have killed Agostinelli had she been aware of his many infidelities. Although he found it difficult to understand how the handsome young Monacan could have fallen in love with such an unappealing woman, this bond confirmed his theory of the subjective nature of love: “Why he fell in love with her cannot be explained, because she is ugly, but he lived only for her.”29 Proust suffered terribly from jealousy over Agostinelli’s love for Anna and over his dalliances with other women that were kept hidden from his wife, but he suffered perhaps most of all from the impossible longings he felt for the youthful, athletic man. The full extent of Proust’s infatuation was finally exposed by tragedy.

During the time Agostinelli stayed in Proust’s employment as his secretary, the writer showered him with money and privileges, despite suffering huge financial losses from his stock market speculations. In letters to friends and publishers, he cautioned them not to mention money matters when writing or phoning. He did not want his servants to know that he was paying to have his novel published—out of pride, perhaps, but also out of prudence.30 Although Proust was extremely generous to the Agostinellis, he did not want them to know anything about his finances, apparently for fear they might demand even more of him.

For the remainder of the year, in letters to friends, male and female, Marcel made oblique references to the kind of suffering he experienced when in love. The first such letter was sent near the end of March to Mme Straus. He wrote first about how “very, very unwell” he had been and of his ancient dream, to which he still clung, of going to Dr. Widmer’s sanatorium. Then, in a likely reference to his feelings for Agostinelli, he told her that he had “a great many other worries too.” These troubles “might be a little less painful if I told them to you. And they are sufficiently general, sufficiently human, to interest you perhaps.” Marcel did not confide in her, however, turning soon to the safe topic of music and his love of Beethoven. He asked her whether she subscribed to the theatrophone. “They now have the Touche concerts and I can be visited in my bed by the birds and the brook from the Pastoral Symphony, which poor Beethoven enjoyed no more directly than I do, since he was completely deaf. He consoled himself by trying to reproduce the song of the birds he could no longer hear. Allowing for the distance between his genius and my lack of talent, I too compose pastoral symphonies in my fashion by portraying what I can no longer see.”31

On March 27 Proust sent a telegram to Odilon Albaret, who was far away in his native village of Auxillac, in Lozère, a rugged, mountainous region in southern France. Proust wanted to congratulate his driver on an event that proved more important to the novelist than he could ever have imagined. Odilon, thirty-one, received the wire just as he set out to the church to marry a young woman named Céleste Gineste.32 Odilon soon returned to Paris with his twenty-one-year-old bride, who, never having left her native village, was to have difficulties adapting to a big city so far from home. The couple took a new, small apartment in Levallois-Péret, on the outskirts of Paris. Near the apartment was a café that stayed open late at night and had a telephone, two necessities for Odilon, who remained on call around the clock, waiting for the summons from Proust.33

By early April, Proust had received his first set of proofs from Grasset. He began to correct them, and soon more proofs arrived. On April 12 Proust wrote to Vaudoyer and admitted that the way he was “correcting” the proofs had surprised him: “My corrections up to now (I hope it won’t go on) are not corrections. Scarcely one line in twenty of the original text (replaced of course by another) remains. It’s crossed out and altered in all the white spaces I can find, and I stick additional bits of paper above and below, to the right and to the left, etc.” He knew that this would mean more expense for his publisher and wondered whether he should offer to pay an extra amount. “If so, how much?”34 In the course of the letter to Vaudoyer, Proust momentarily confused his correspondent’s article on Russian Ballet with another on Gautier. He attributed such slips to the “abuse of veronal, aspirin and anti-asthmatic powders.”

On Saturday evening Marcel wrote Antoine about the concert he had just attended at the Salle Villiers: “Great emotion this evening. More dead than alive I nonetheless went to a recital hall . . . to hear the Franck Sonata which I love so much.” The piece was César Franck’s 1886 Sonata in A major for Piano and Violin, performed by the renowned Romanian violinist Georges Enesco and the French pianist Paul Goldschmidt. Proust had never heard Enesco, and he found his playing “wonderful; the mournful twitterings, the plaintive calls of his violin answered the piano as though from a tree, as though from some mysterious arbour. It made a very great impression.”35 Perhaps inspired by the rondeau from Franck’s sonata, Proust added a few lines, on galley number 50, to his description of Vinteuil’s sonata.36 Years later, when inscribing an original deluxe edition of Swann’s Way to a young friend, Jacques de Lacretelle, Proust provided a fairly detailed account of the music that inspired Vinteuil’s compositions. He mentioned, as one source of inspiration, Franck’s sonata, as played by Enesco, where the “piano and the violin moan like two birds calling each other.”37

Proust made an effort to strengthen his ties to Mme Marie Scheikévitch. In May he accepted an invitation to dinner, where he amused her guests by making witty comments on a verse line about flowers from Montesquiou’s Hortensias bleus, in which the poet juxtaposed names of flowers with colors of the same name: “Oh, les lilas lilas! le bleuet bleu! la rose Rose!” The next day Marie sent him a “marvelous bunch of lilacs.”38 Writing to thank her, he promised to detach from the proof pages of his book “(which no one but you has seen) a few ‘lingering and invisible’ lilacs.” By the end of the letter, Proust had to admit that he was unable to find his pages about lilacs but said that would send them later. He recalled a vision of Marie at a recent performance by the Ballets Russes where she had been holding red roses close to her white dress. He had been touched by that reminder of how much she had suffered during her marriage and suicide attempt.39 “I was saying the other day, remembering how your life was once stained with blood, that when I caught sight of you in the distance with that great bouquet of red roses like a wound at your heart, you reminded me of a transpierced Dove.” He recalled the day long ago when he had seen such birds on an outing with Reynaldo to the zoo in the Jardin des Plantes. Remembering all the martyrs to love—Reynaldo’s explanation for the crimson breasts of the dove—Proust had considered and then abandoned Transpierced Doves as a title for his second volume.40

Proust encountered Jacques Copeau on May 22 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, where both were attending the première of a new production of Boris Godunov, featuring Fyodor Chaliapin. Proust had not shaved for a week and so sat in the stalls wearing his fur coat throughout the performance.41 He had recently assisted Copeau by making contacts with a number of potential contributors to his new enterprise, the creation of the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier. After the opera, Proust, who had bought three shares in Copeau’s theater, sent him a letter and 750 francs as payment for the first share.

In his fruitless attempts to have the NRF publish his novel or excerpts from it, Proust feared that Copeau had misunderstood the use of memory in his novel. “The memory to which I attach so much importance is not at all what is usually meant by the term. The attitude of a dilettante who is content to delight in the memory of things is the opposite of mine.” Proust told Copeau that by “reading myself I’ve discovered after the event some of the constituent elements of my own unconscious.” As an example of what he did not mean, he cited a remark that Dostoyevsky made about Raskolnikov, hesitating at the door of the old money-lending woman he is about to kill. Dostoyevsky had written: “the memory of that moment would always remain with him.” That memory, Proust explained to Copeau, “is still something extremely contingent and accidental by comparison with ‘my’ memory, in which all the physical components of the original experience are modified in such a way that from the point of view of the unconscious the memory takes on, mutatis mutandis, the same generality, the same force of higher reality, as the law of physics, through the variation of circumstances. It is an act and not a passive sensation of pleasure.”42 Proust stressed this point because in his novel he intended to reconstruct and interpret past experience, not indulge in tranquil moments of nostalgia.

During the last week in May, Proust and Grasset exchanged letters about progress on the proofs. Earlier in the month Proust had returned the first batch of corrected proofs. Grasset sent an urgent request that the proofs be returned without delay; with so many corrections to make, no time must be lost. Proust had resigned himself “to returning to you these lamentable proofs which fill me with shame.” But he had settled on his titles: “The first volume will be called Du côté de chez Swann. The second part probably Le Côté de Guermantes. The overall title of the two volumes: À la recherche du temps perdu.”43 He told Grasset that when all the proofs had been corrected, he would add the dedication to Calmette.44 He requested that Grasset draw his staff’s attention to the “very fragile” nature of his proofs: “I’ve stuck on bits of paper which could easily tear, and that would cause endless complications. There are galleys which may seem to be half-missing. This is because I’ve transferred a passage elsewhere.” He had abandoned “Intermittences du cœur” in favor of the new general title, but would reserve it as a chapter title for a later volume.45

Proust complained to Maurice Duplay about being “broken” by the correction of his proofs, a task that seemed endless because he was “changing everything, the printer can’t make any sense out of it, my editor hurries me from day to day, and during this time my health has degraded entirely and I have grown so thin you would not recognize me.”46 As he diminished physically, Proust became alarmed by the length of the first volume and proposed that the dialogue be incorporated into the text without breaks. Grasset reluctantly agreed to this, but Louis de Robert was horrified and thought the best solution was to print “Combray” separately in one volume of roughly normal length.47 Writing to Grasset, shortly after May 24, Proust said that for the second round of corrections, he would restrict himself to changing a few names. But this wise resolution would not be kept.

Proust admired duelists and so took notice in early June when his publisher fought a duel because he thought that one of his authors had been unfairly attacked. The offender was Henry Postel du Mas, editor of Gil Bias, who had written a series of articles unfavorable to Émile Clermont, author of Laure. Clermont was in a close contest with Romain Rolland for the Grand Prix awarded by the Académie française. When Rolland won by a narrow vote, Grasset, who felt that the critic’s attacks must have influenced the outcome, challenged Mas to a duel. The combat ended when Grasset received a sword cut in the arm.48 Proust, who thought that such energy and devotion boded well for his novel, wrote Grasset to congratulate him, saying that he did not pity him because he knew from experience “how agreeable such occasions are; a duel is one of my best memories.”49

Grasset wrote Proust on June 19, telling him that he had glanced at the proofs and noticed that quite a few were still missing from the galleys of the first proofs that the author had corrected. Of the ninety-five galleys that had been sent to Proust, only forty-five had been returned to the publisher.50 But out of the forty-five returned, thirty-three galleys had been sent back to Proust as second proofs. Grasset felt uncomfortable having two versions of the same text in circulation at the same time and urged Proust to finish correcting the first proofs. Proust asked to be charged for the extra work on the proofs and received a bill from Grasset for the revisions to date that totaled 595 francs.51

Proust asked Louis de Robert’s advice regarding the myriad solutions to the endless lengthening of his book. After telling Louis that he alone of all his friends would see the entire book before publication, Proust asked him to identify passages in the proofs that seemed too long and could be cut or, perhaps, relegated to notes. He had run the dialogues in, a measure Grasset found very “ugly,” but one that Proust claimed was an improvement because his characters’ remarks became part of “the flow of the text.” Proust, desperate for remedies, later abandoned such extreme solutions to the problem of publishing an unusually long volume. He did not promise to accept Louis’s suggestions: “Perhaps I will disobey you because finally I can only obey myself.” But he did admit that he had been unable to send the proofs any sooner because he had used them to write a “new book.” He then alluded discreetly to his lovesickness over Agostinelli: “I am very ill and what’s more I have a lot of sorrow.”52

By late June, Proust sent Grasset 595 francs and admitted that if Swann’s Way were published in its present form, it would exceed seven hundred pages, the limit that he and Grasset had set. He saw the necessity of transferring to the “second volume what I thought would be the ending of this one (a good ten galleys). But you yourself are too much of an artist not to realize that an ending is not a simple termination and that I cannot cut the book as easily as a lump of butter. It requires thought. As soon as I’ve discovered how to end, very shortly... I shall return both the first and the second proofs.”53

Louis de Robert had received from Proust a clean set of second proofs for the first forty-five galleys. Robert read them in amazement as he watched this extraordinary novel expand and take shape. He wrote Proust: “I am still lost in admiration. And I urge you most strongly: make it two volumes of 350 pages each.” As for shortening the text, he gave this advice: “Don’t cut anything—it would be a crime. Everything must be kept; everything is rare, subtle, profound, true, right, precious, incomparable. But do not pour such a rare liquor into such a big glass.” Robert was afraid that most readers would skim a book of seven hundred pages and thus miss “untold beauties, untold original insights, untold observations of astonishing perceptiveness and truth.” He had no doubt that “this work will rank you among our foremost writers, and I am deeply delighted.” Robert did have one complaint; he hated the title Swann’s Way, finding it “unbelievably commonplace!”54

Soon Louis had another concern. He had apparently learned from Maurice Rostand about the homosexual scenes that occur later in the novel. The anticipation of those, added to Mile Vinteuil’s lesbian love ritual, a scene to which he had always objected, made him fear for the reception of Proust’s novel.55 Proust explained his position of pure objectivity: “I obey a general truth which forbids me to appeal to sympathetic souls any more than to antipathetic ones; the approval of sadists will distress me as a man when my book appears, but it cannot alter the terms in which I probe the truth and which are not determined by my personal whim.” He denied a “gift for minute details, for the imperceptible,” attributed to him by Louis and others, claiming that he omitted “every detail, every fact, and fasten [ed] on whatever seems to me . . . to reveal some general law.” He gave the example of “that taste of tea which I don’t recognize at first and in which I rediscover the gardens of Combray. But it’s in no sense a minutely observed detail, it’s a whole theory of memory and perception.” He attempted to explain his title Swann’s Way: “The point of the title was because of the two ways in the neighbourhood of Combray. You know how people say in the country: ‘Are you going round by M. Rostand’s?’” It still bothered him that Louis did not like the title, and in the postscript Proust suggested alternative titles.56

In subsequent letters Proust continued to defend his title. Louis failed to appreciate how perfectly Swann’s Way suited the author’s needs both thematically —the explorations of bourgeois society (Swann’s Way) and that of the nobility (The Guermantes Way)—while opening windows on French history and contemporary society. The structural function of the two ways (côtés) is vital. As a child the Narrator thinks that the two ways, the walk past Swann’s place and the more distant excursions by the Guermantes castle, lie in opposite directions and are distinct geographical unities. In the concluding volume, Gilberte Swann shows him that the two ways are linked geographically and form a circle, just as her marriage to Saint-Loup, a Guermantes, represents the symbolic and biological union of the two ways.

Proust and Robert exchanged further letters regarding homosexuality in the novel. Although Robert’s comments revealed him to be somewhat prudish, he was also motivated by a genuine concern that Proust’s novel might be shunned because it treated subjects normally considered taboo. Proust tried again to allay Robert’s fears about his treatment of sadism and homosexuality: “If, without the slightest mention of pederasty, I portrayed vigorous adolescents, if I portrayed tender fervent friendships without ever suggesting that there might be more to them, I should then have all the pederasts on my side, because I should be offering them what they like to hear! Precisely because I dissect their vice (I use the word vice without any suggestion of blame), I demonstrate their sickness, I say precisely what they most abhor, namely that this dream of masculine beauty is the result of a neurotic defect.”57 Proust’s prophecy was accurate; Gide later reproached him for his depiction of homosexuality for precisely these reasons.

On July 26 Proust left suddenly for Cabourg. He described the difficult trip to Reynaldo, to whom he wrote immediately after his 5:00 A.M. arrival: “I’m writing to you after a terribly exhausting journey, the motor-car losing the way, etc., at five in the morning, having just arrived in this hotel to which I’ve come back for the sixth time and where I’m very comfortable.” He told Hahn about having telephoned Mme Jacques Bizet in an effort to find employment for Robert Ulrich, who was “starving to death.” He expressed his affection for Reynaldo—“Much love, my dear Guncht”—but said that his letters would be “few and far between as Grasset is clamouring for my proofs, which I haven’t begun!”58 Agostinelli’s troubling presence made it difficult for the writer to concentrate on his work.59

But Proust had little time to enjoy the Grand-Hotel’s comfort. On August 4, a little over a week after his arrival, while he and Agostinelli were on their way to Houlgate, Proust decided to return immediately to Paris without informing anyone at the hotel. Shortly after his arrival back in the capital, he wrote this account to Charles d’Alton: “It was on the way to Houlgate that suddenly my regret at not being in Paris came back to me so strongly that in order to avoid further hesitations I decided to leave there and then without bag or baggage and without returning to the hotel. I went into a café with Agostinelli and sent a message to Nicolas and Agostinelli sent one to his wife, who joined us after a few hours.” Proust prudently asked Alton not to tell anyone that Agostinelli was in his employ as a secretary.60 A week later, Proust gave a slightly different account to Lauris, saying that when he went to Cabourg, he had left behind “a person whom he rarely saw in Paris and at Cabourg I felt far away and anxious.” So he decided to return to Paris, but kept postponing the departure. Then he and “Agostinelli had set off to do some shopping in Houlgate, where he thought I looked so sad that he told me I ought to stop hesitating and catch the Paris train at Trouville without going back to the hotel.”61 Nothing more is known about this bizarre episode, except that it recalled Proust’s state of mind when traveling with Bertrand de Fénelon in Holland. Then, miserable and afraid of making Fénelon unhappy by his despondency, he had sent his friend away. Perhaps being constantly in Agostinelli’s company in Cabourg reminded him too forcefully of the impossible nature of the love he felt for his secretary. In Paris, Agostinelli would still be in Proust’s apartment, but in his presence only when summoned. This situation, which neither man found tolerable, was not to last much longer.

Proust wrote to Nahmias about his sudden return to Paris, where he thought he would stay only a day or two before traveling elsewhere. He now realized that his severe weight loss made another trip too dangerous for his health. In the postscript Proust told Nahmias not to talk about his secretary. “People are so stupid they might see in it (as they did in our friendship) something pederastic. That would make no difference to me, but I would be distressed to place this boy in a bad light.” Then, almost as an afterthought, he mentioned that he had dined alone at Larue’s, where he had seen a friend of Nahmias’s with a blonde whom he found ravishing.62 Proust’s thoughts remained centered to a large degree on his unrequited love for Agostinelli. Though certain that his novel would at last appear, Proust was miserable. Later in August he complained to Charles d’Alton about enduring relentless “mental sorrows, material problems, physical suffering, and literary nuisances.”63 He dared not confide the real reasons for his unhappiness.

The year 1913 is known in French aviation history as the Glorious Year. On September 23 Roland Garros became the first aviator to fly across the Mediterranean, and French flyers flew nonstop from Nancy to Cairo. A new speed record of 203 kilometers per hour was set and pilots reached altitudes of six thousand meters. Aerodromes were opened at Buc, near Versailles, and at Issy, drawing crowds of the curious, the idle rich, and brave young men like Agostinelli, who saw a new frontier opening up before them and were eager to fly the new machines.64 Proust tried to dissuade Agostinelli from taking flying lessons, but his objections were overruled by Anna’s determination; she thought that the couple would become fabulously wealthy if her husband could learn to fly an airplane.65 Proust had warned Agostinelli: “If ever you have the misfortune to have an aeroplane accident, you can tell your wife that she will find me neither a protector nor a friend and will never get a sou from me.”66

Céleste knew about Agostinelli’s passion for sports and his daredevil nature through her husband, Odilon, who had been working with Agostinelli periodically for years.67 Thanks to Proust’s generosity, Agostinelli was able to take flying lessons at Buc, where Roland Garros had an aviation school. Because Agostinelli no longer owned a car, Proust paid Odilon to drive his secretary to and from the airfield.

During the fall, Agostinelli grew restless under Proust’s constant surveillance. The sedentary existence of typing a manuscript was hardly the job for a future aviator. He must have spoken at some point of returning home and obtaining his pilot’s license at one of the aviation schools that had opened near Monte Carlo. Proust, desperate to keep the young man near him at all costs, did everything possible to make such opportunities available to the young flyer in Paris. He may have hinted at buying Agostinelli a Rolls-Royce if he wanted to resume his profession as a driver, and even an airplane for a career as a pilot.

Toward the end of August, Marcel wrote to Lucien Daudet, saying that he should have contacted Lucien first for his research because he was so knowledgeable: “And doubtless writing to you would have spared me the interminable correspondence I’ve had with horticulturists, dress-makers, astronomers, genealogists, chemists, etc., which were of no use to me but were perhaps some use to them because I knew a tiny bit more than they did.” Proust lamented the “stupid division” of Swann’s Way and feared that no one would be capable of judging his work until its publication in three volumes, a number he now accepted as necessary. He was not eager for Lucien to read the proofs for Swann’s Way because he knew that “if one reads a book, one doesn’t reread it, and there will be last-minute improvements here and there which I’d like you to be aware of.” He then turned to more personal matters, saying that he had been “very ill, very troubled, very unhappy.” He would not send another letter: his doctor had ordered him to avoid corresponding because he needed “to regain thirty kilos (!)”68 Proust could no more stop letter writing than he could reform other aspects of his schedule that undermined his health. The emotional stress that resulted from months of having Agostinelli and Anna in his apartment during this period when he worked so hard on his book had contributed to Proust’s phenomenal and alarming weight loss. Nearly every letter he wrote to a close friend that year and next referred to his severe thinness and his unhappiness. Given his lifestyle, regimen, and ailments, it was hardly surprising that he had begun to waste away.

As soon as Lucien read this letter, he begged Proust to send him the proofs as quickly as possible. Two days later they arrived, and Daudet spent that day and part of the night devouring Swann’s Way. Afterward Lucien had the impression that he had taken a voyage rather than read a book. He wrote immediately to Marcel to tell him that the novel had “dazzled” him.69 Lucien offered to write an article about Swann’s Way as soon as it appeared. Marcel, who always melted whenever anyone showed him kindness, was unable to resist the combination of gentillesse and enthusiastic appreciation of his novel.

Marcel began writing long letters of gratitude to Lucien, revealing many details about the remainder of the Search, including its plot.70 In one letter he asked, “My dear Lucien, how shall I ever be able to thank you?” He then inquired whether he could send the new conclusion of Swann’s Way, for which he had taken some pages from later in the book. He was eager for Lucien to tell him whether these pages made a better ending.71 The lines Proust had chosen describe a scene where the Narrator, much older and in a nostalgic mood, returns to the Bois de Boulogne, where he used to wait to see Mme Swann pass by. But now everything has changed; not only does she no longer come there, but the horse-drawn carriages have been replaced by noisy automobiles, and the women wear garments he finds much less appealing than the splendid outfits Mme Swann wore. This new state of things leads the Narrator to conclude: “The places we have known do not belong only to the world of space on which we map them for our own convenience. They were only a thin slice, held between the contiguous impressions that composed our life at that time; the memory of a particular image is but regret for a particular moment; and house, roads, avenues are as fugitive, alas, as the years.”72

In another September letter, Proust showed signs of author’s jitters; he worried that Lucien and others could not possibly comprehend the scope of his work from reading Swann’s Way: “Not only is the work impossible to grasp from this first volume alone, which acquires its full meaning through the others, but the proofs are uncorrected and teeming with misprints, and there are some very important little incidents missing especially in the second part which tighten the knots of jealousy around poor Swann. And even when it’s ready to appear, it will be like those themes in an overture which one doesn’t recognize as leitmotifs when one has only heard them in isolation at a concert, not to mention all the things that will find their place after the event (thus the lady in pink was Odette, etc.).”73

Louis de Robert again urged Proust to delete the lesbian profanation ritual scene because it would delight pederasts and sadists. Using scientific analogy, Proust defended himself by saying that he served a higher cause. It would be unethical to falsify the results of experiments: “I cannot, in the interest of a friendship which is most precious to me, or to displease an audience which I find antipathetic, modify the results of psychological experiments which I am bound to communicate with the probity of a scientist.”74 One can hear Dr. Proust’s voice in Marcel’s insistence on finding the truth by using rigorous scientific methods.

Sometime during the fall, Proust finally purchased an Aeolian automatic piano player, which was adapted to the grand piano he kept in his room. It seems likely that he did so in part to amuse Agostinelli, who must have pumped the instrument for Proust, as Albertine was later to do for the Narrator. Much to the exasperation of the piano roll suppliers, Proust began to ask for pieces that had never been requested before, such as the piano transcription of Beethoven’s late quartets. In early January he complained to Mme Straus about the lack of such rolls: “My consolation is music, when I’m not too sad to listen to it: I’ve completed the theatrophone with a pianola. Unfortunately they happen not to have the pieces I want to play. Beethoven’s sublime XlVth quartet doesn’t appear among the rolls.”75

One September day when Odilon and Céleste were out for a stroll, Odilon decided that they should stop by boulevard Haussmann and inform Nicolas of their return to Paris and Odilon’s eagerness to resume work. Nicolas, who admitted them through the servants’ entrance into the kitchen, “insisted on announcing that Odilon was there.” Céleste recalled the first meeting: “M. Proust. . . was wearing only a jacket and trousers and a white shirt. But I was impressed. I can still see that great gentleman enter the room. He looked very young—slender but not thin, with beautiful skin and extremely white teeth, and that naturally formed curl on his forehead, which he always would have.” After Odilon greeted him, Proust noticed Céleste and “held out his hand and said, ‘Madame, may I introduce Marcel Proust, in disarray, uncombed, and beardless.’” After the brief encounter, Céleste asked Odilon: “Why did he say ‘beardless’?” Odilon replied that Proust had worn, until quite recently, “a magnificent black beard.”76

On October 10 Louis Brun informed Proust that he had received all proofs from the third set and was sending them on to the printer’s with “all your instructions for the new series of proofs that will be sent to you during the week.” Brun, eager to speed up the process, pointed out that the “first 257 pages have very few changes” and could be sent to the printer’s with the author’s “bon à tirer” (permission to print). He asked Proust to indicate how many of those pages could safely be dispatched for final composition.77 A week later, Grasset asked whether Proust would like to have any deluxe copies printed.78 Marcel, uncharacteristically conservative, decided to have five copies printed on Japan Imperial paper and twelve on rice paper. Still concerned about the clearest way to announce a work in several volumes, Proust consulted André Beaunier, who suggested that he call it a trilogy. Proust adopted this solution. The announcement carried the general title as well as Swann’s Way, and announced the titles of the remaining volumes, The Guermantes Way and Time Regained.

Proust, who had continued to lose money on the Bourse, found himself obliged on October 12 to sell all the Royal Dutch shares held for him by the Warburg Bank in order to pay his rent. Because he remained so unhappy, Proust thought of fleeing Paris and began to inquire about property to rent in Italy. He had not been as unstable and miserable since the period following his mother’s death.

Grasset told Proust that he would like to submit Swann’s Way to the selection committees of the two major literary prizes awarded in December, the Fémina and the Goncourt. Proust complained to Barrès that just at this time, when he was nearly incapable of thinking about the publication of his book, he now must obtain the addresses of jury members and contact them. Was it even proper, he wondered, to submit a book like his, with its unchaste pages, to a committee such as that of the Fémina, presided over by a woman, Mme de Pierrebourg?79 He was to have the same reservations about sending Swann’s Way to his younger female friends.

Grasset wrote on October 25, saying that Proust had made so many changes that a new set of proofs was needed, the fourth. He also had some good news. Because his original estimate had assumed a volume of 800 pages—a number now reduced to roughly 530—Grasset was increasing the print run from 1,250 to 1,750. Proust would thus have 250 extra copies to use for the press or give to acquaintances, and 1,500 copies to sell.80 A few days later, Grasset apologized profusely for presenting Proust with a bill for the four sets of proofs totaling 1,066 francs, of which 595 francs had already been paid. Grasset explained what Proust already knew, that normally such costs are negligible and easily covered by the publisher. Seldom if ever had there been so many galleys and proofs and complicated revisions. By the time Proust had completed his work on volume one, Grasset was to send him a fifth set of proofs.81 Grasset proposed to publish Swann’s Way around November 15 if he and Proust could arrange for publicity and reviews, and be certain of obtaining adequate shelf space in bookstores, soon to be crammed with gift books for the holidays.

On October 29 or 30 Grasset finally had a brief interview with the man who was to be his most famous author. Eager to launch the publicity campaign, Grasset and Proust looked over the list of potential reviewers. Ideally, Swann’s Way should be reviewed by André Beaunier in the Figaro and Paul Souday in the Journal des débats.82 Beaunier disappointed them by deciding to wait until the entire novel appeared before giving his opinion.83 Souday wrote a review that infuriated Grasset and Proust.

In letters to Blum and Robert de Flers written in early November, Proust stressed the great importance he attached to this book, into which he had put “the best of myself, my thought, my very life.”84 He told Blum that everything he had written previously amounted to nothing. This new book was an “extremely real work but propped up, as it were, to illustrate involuntary memory.” Proust remarked that although Bergson did not make this distinction, in his view it was the only valid one; he then explained the role involuntary memory played in his novel. He also wanted Blum to understand—a point he would make to other reviewers and readers—that this book was “real, passionate,” and “very different from what you know of me, and, I think, infinitely less feeble, no longer deserving the epithet ‘delicate’ or ‘sensitive’ but living and true.” Such adjectives had hounded him since the publication of Pleasures and Days, and, knowing what creatures of habit critics can be, he wanted to insulate his new book from those inappropriate and deadly words. Proust made a similar request to Robert de Flers when he announced the book in the Figaro.

On November 8 Grasset asked Proust to send advance copies to the prize committees of Fémina and Goncourt. Among his friends who received autographed copies were Georges de Lauris, Bertrand de Fénelon, posted at the French embassy in Cuba, and Mme de Pierrebourg, with whom he discussed by letter the Fémina, as well as the Goncourt, observing that it was probably already too late to apply. Then he expressed his great fear that no one would read his book because it was so long and dense.85

Proust may not have been entirely pleased at Blum’s preview in the Gil Bias on November 9, just five days before publication. Blum described Swann’s Way as “the first in a series . . . combining an elegant, ironic study of certain aspects of society and an evocation of tender landscapes and childhood memories.”86 The juxtaposition of “tender landscapes and childhood memories” bothered Proust. Although the relationship between the Narrator and his mother was certainly loving, the Combray landscape contains a number of elements that are far from tender—such as the abandoned and foreboding dungeon of Roussainville, to which, as the Narrator later learns, girls and boys of the village sneak away and engage in youthful sexual experiments. When the child Narrator sees Gilberte for the first time across the hedge, standing in her father’s garden, she makes an obscene gesture, which he fails to interpret correctly. The Combray landscape also embraces Montjouvain, where the young Narrator unintentionally spies on the lesbian lovers who profane images of M. Vinteuil.

Before writing the blurb Blum had visited Proust and listened to him read the most famous passage from the “Combray” section, the madeleine scene. Although incorporated within the pages called “Combray,” the scene is not anchored in any definite narrative sequence. It begins, after a break, with a sentence that treats the paucity of voluntary memory: “And so it was that, for a long time afterwards, when I lay awake at night and revived old memories of Combray, I saw no more of it than this sort of luminous panel.”87 When Proust’s voice grew tired, he asked Blum to read the conclusion of the madeleine scene: “When from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more immaterial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.”88

On November 8 Proust, who did not rise from his bed, received Élie-Joseph Bois, a reporter from the Temps, and spoke to him for an hour and a half about “a thousand things.”89 The newspaper’s editor Adrien Hébrard, who was Marie Scheikévitch’s lover, had arranged for the interview as a favor to her.90 The primary topic of conversation was, of course, Swann’s Way. The author explained his views on time, characters, and style. Throughout the interview, Proust quoted passages from Swann’s Way and remaining volumes, perhaps hoping to thwart criticisms about the lack of a plot by showing some of the lessons the Narrator learns by the novel’s end.91

In the interview Bois raised readers’ expectations about the novel by saying that the copy passed around to “privileged readers” had provoked great enthusiasm.92 The interviewer wondered whether the book was “a masterpiece, as some had already called it.” He also predicted that Swann’s Way would “disconcert many readers.” Though “a book of true originality and profundity to the point of strangeness, claiming the reader’s full attention and even seizing it forcibly,” Proust’s novel lacked a plot in the usual sense “of what we rely on in most novels to carry us along in some state of expectation through a series of adventures to the necessary resolution.” Instead, Swann’s Way was a “novel of analysis,” “so deep” that “at times you want to cry out, ‘Enough!’ as to a surgeon who spares no detail in describing an operation. Yet you never say it. You keep on turning the pages feverishly in order to see further into the souls of these creatures. What you see is a certain Swann in love with Odette de Crécy, and how his love changes into an anxious, suspicious, unhealthy passion tormented by the most atrocious jealousy.” Bois told his readers that with Proust “we aren’t kept on the outside of things;... we are thrust into the mind and heart and body of that man.” The interviewer also mentioned similar experiences with a “child’s love for his mother, and with a boy’s puppy love for one of his playmates.... M. Marcel Proust is the author of the disturbing book.”

Bois provided a brief summary of Proust’s previous work, reprising the hothouse image from France’s preface to Pleasures and Days to illustrate that the writer had matured: “Marcel Proust, intent upon himself, has drawn out of his own suffering a creative energy demonstrated in his novel.” The interviewer described the novelist “lying down in a bedroom whose shutters are almost permanently closed. Electric light accentuates the dull color of his face, but two fine eyes burning with life and fever gleam below the hair that falls over his forehead.” Although “still the slave of his illness . . . that person disappears when the writer, invited to comment on his work, comes to life and begins to talk.”

Proust wanted potential readers to know that his attempts to bring out all his volumes together had failed because publishers were reluctant to issue “several volumes at a time.” Proust explained his notion of the importance of time in his work: “It is the invisible substance of time that I have tried to isolate, and it meant that the experiment had to last over a long period.” He gave an overview of his work that showed the union of characters belonging to different social worlds, his presentation of people seen in multiple perspectives, and his concept of multiple selves. “From this point of view,” he remarked, “my book might be seen as an attempt at a series of ‘novels of the unconscious.’ I would not be ashamed to say ‘Bergsonian novels’ if I believed it . . . but the term would be inaccurate, for my work is based on the distinction between involuntary and voluntary memory, a distinction which not only does not appear in M. Bergson’s philosophy, but is even contradicted by it.” Proust used the madeleine scene as an example of the extraordinary richness of involuntary memory experiences, indicative of marvelous resources that lie within.

Proust provided examples of the aesthetic lessons the Narrator learns during his long quest to become a creative person. Bois ended with another view of the “ailing author” in his shuttered room, “where the sun never enters.” Although the invalid might complain, the “writer has reason to be proud.”

A week later Proust granted a second interview, also from his bed, to André Lévy, with whom he talked for an hour.93 This one appeared in the Miroir on December 21. Lévy, who wrote under the pseudonym André Arnyvelde, like Bois noted the pallor of the writer’s face. He also mentioned for the first time in print the cork-lined room that was to become legendary. Exaggerating Proust’s reclusiveness, Arnyvelde wrote that the writer had retired from the world many years ago to a “bedroom eternally closed to fresh air and light and completely covered with cork.” Proust was quoted as saying that his reclusion had benefited his work: “Shadow and silence and solitude ... have obliged me to re-create within myself all the lights and music and thrills of nature and society.”94

Arnyvelde, who seemed interested in Proust’s working arrangements, described the large bedside table: “Loaded with books, papers, letters, and also little boxes of medicine. A little electric lamp, whose light is filtered by a green shade, sits on the table. At the base of this lamp, there are sheets of paper, pen, inkwell.” The array of items may have been ordinary, but not the author’s practice of writing at night, and always in bed. The interviewer was struck by Proust’s “big invalid’s eyes that shine beneath the thick brown hair that falls untidily on the pale forehead.”

Proust again outlined his novel and what he had hoped to achieve in writing it. He used Vinteuil as the example of his method of characterization; this apparently dull and banal bourgeois is discovered to be a musical genius. He also made the distinction, first delineated in the essay attacking Sainte-Beuve, between the social self and the creative self. Both interviews stressed the key Proustian point that we must delve deep within ourselves to discover our richest resources.

On November 12, two days before publication, Proust encouraged Calmette to arrange for the novel to be mentioned in the Figaro. Back in March the newspaper had published excerpts from Swann’s Way and The Guermantes Way that Proust had edited to create a selection called “Vacances de Pâques” (Easter vacation). But with publication close at hand, Proust told Calmette that it was somewhat “sad to see that the Figaro is the only newspaper” among those in which literature occupied something of a place that had not announced his novel. Should Calmette insert something, he begged him to avoid the epithets fine and delicate and any mention of Pleasures and Days.95

Friday, November 14, was marked by two major events in Proust’s life, although the importance of the second was not apparent. The first, of course, was the publication of volume one of his novel. The second event, of which Proust took little notice, was Céleste Albaret’s assistance in distributing the copies of Swann’s Way. Proust’s brother Robert had performed gynecological surgery on Céline Cottin that day. The writer asked Céleste, who had come as a temporary replacement for Céline, to go with her husband in his taxi and deliver the inscribed copies of Swann’s Way to his friends. Céleste, who had been in Paris for only a few months when she met Proust for the first time, was still afraid of big-city life. She missed her family, especially her mother, and was happy to have something with which to distract herself. From then on Céleste came to 102, boulevard Haussmann to work from nine to five while Proust slept.96 Nicolas Cottin still waited on Proust personally during hours that matched more closely his employer’s nocturnal schedule.

Bernard Grasset had always been professional and courteous in his relations with Proust, but for him the publication of this novel was a business deal. He had tried to read the volume and had found it impenetrable. Grasset had performed his duties well in preparing for publication of Swann’s Way, but his expectations for sales must have been low. He had told Charles de Richter, a boating friend to whom he gave an advance copy: “It’s unreadable; the author paid the publishing costs.”97

In the week following publication, Proust told Louis de Robert that Grasset had shown himself to be “intelligent, active and charming.” But Proust complained about an announcement for bookstores that Grasset had printed without consulting him, “which could not be more objectionable from my point of view.” Proust, who had received a copy of the notice from Argus, a clipping service to which he now subscribed, asked Grasset to withdraw this notice, though he feared it was too late: “After a long silence due to his voluntary retirement from life, Marcel Proust, whose debut as a writer elicited unanimous admiration, gives us, under the title, À la recherche du temps perdu, a trilogy of which the first volume, Swann’s Way, is a masterly introduction.” Proust considered “voluntary retirement” untrue and objected to the reference to his “debut,” which might remind the public of Pleasures and Days.98

Proust’s dedication to the man who had first opened the pages of the Figaro to him read: “To M. Gaston Calmette, as a token of profound and affectionate gratitude.” Gaston, who had appeared indifferent to the splendid cigarette case, never bothered to acknowledge the dedication of Swann’s Way.99 Calmette was engaged in a nasty political press campaign that was to have tragic results. In Mme Straus’s copy Proust wrote, “To Mme Straus, the only one of the beautiful things I already loved at the age where this book begins, for whom my admiration has not changed, no more than her beauty, no more than her perpetually rejuvenated charm.”100 He addressed Robert’s copy “To my little brother, in memory of Time lost, regained for an instant each time we are together. Marcel.”101 To Lucien he explained why his “dear little one” was “absent from this book: you are too much a part of my heart for me to depict you objectively, you will never be a ‘character,’ you are the best part of the author.”102 The dedication to Reynaldo is unknown, but certainly it could have expressed the same sentiment, for no one was closer, nor ever would be, to Marcel. Yet in one sense both Reynaldo and Lucien were very much present in the book. Proust had suffered with each of them the tormenting, debilitating jealousy that nearly destroys Swann during his obsession with Odette.

On the day the novel appeared, Léon Daudet, a key figure in any deliberations of the Prix Goncourt committee, wrote his friend Marcel to explain that a majority of the committee objected to voting for an author older than thirty-five. Proust was forty-two. In stating this objection, the members of the Académie Goncourt were following what they believed to be their duty. In his will establishing the prize, Edmond de Goncourt had stated his “supreme wish” that the “prize be awarded to young writers, to original talent, to new and bold endeavors of thought and form.”103 Proust clearly met all the requirements except youth.

Letters written to Robert de Flers, Jean-Louis Vaudoyer, and Anna de Noailles around the time of publication show Proust still profoundly unhappy and making plans to leave Paris and even France. He had recently asked Vaudoyer by mail whether he knew of a “quiet, isolated house in Italy, no matter where, I should like to go away.” He then inquired about renting one of the most splendid Renaissance palaces in Italy: “You don’t happen to know if that Farnese palace (the Cardinal’s), at a place which I think is called Caprarola, is to let? Alas, at the moment when my book is appearing, I’m thinking of something utterly different.”104 Proust had apparently read a recent article in the Revue de Paris saying that the Palazzo Farnese in the hill village of Caprarola, near Viterbo, had been restored and rented to a rich American. Such extravagance seems foolish, given Proust’s precarious financial condition, but he was completely demoralized. He wrote Flers that he did not even have the energy and will to recopy the last two volumes of his novel, which were “completely finished.” He confided that he had rented a property somewhere outside of Paris, but could not decide to leave.105 Thanking Anna de Noailles “infinitely for having written him” about his novel, he told her that his book “enjoyed no success.” Even if it were to succeed, he would take no joy from it because he was “too sad at present.”106 Proust’s distraction resulted from his un-happiness over his relationship with Agostinelli.

Proust had expressed his affection to the young man through constant generosity and favors. But he wanted the impossible—a reciprocated love and devotion. He felt Agostinelli pulling away from him, resentful of his constant and needy presence. Proust knew that the situation was hopeless, but his marvelous lucidity and intelligence remained powerless to unshackle the chains of desire and jealousy that bound him to his secretary. He had depicted Swann’s obsessive love for Odette as a malady and then had again caught the disease himself. He believed, according to the image he used for Swann, that the source of the pain within him was “inoperable.”

Proust had taken the trouble to send copies of his novel to the group of men who had shunned him, but whom he still wanted to impress more than any other because they were writers. The day after Swann’s Way was published, he informed Jacques Copeau that he had sent copies for him, Gallimard, and Gide, as well as for M. Paul Claudel, the poet and playwright, whom he “knew only slightly but admired profoundly.”107 While he had Copeau’s attention, Proust deplored an indiscretion of Gide’s.108 Word had reached Proust that Gide had gossiped about a matter relating to Copeau’s rejection of his excerpts for the NRF, a matter Proust and Copeau had agreed to keep confidential. He told Copeau that if Gide knew how many times Proust had tried to refute, for Gide’s sake, stories about Turkish baths, Arab boys, and ship’s captains on the Calais-Dover run, perhaps Gide would have been more circumspect in tattling about him.109 Not surprisingly, Proust was well informed about Gide’s reputation as a homosexual.

On November 21 Reynaldo wrote to Mme Duglé, Charles Gounod’s niece, to express an opinion and make a prediction: “Proust’s book is not a masterpiece if by masterpiece one means a perfect thing with an irreproachable design. But it is without a doubt (and here my friendship plays no part) the finest book to appear since l’Éducation sentimentale. From the first line a great genius reveals itself and since this opinion one day will be universal, we must get used to it at once. It’s always difficult to get it into your head that someone whom you meet in society is a genius. And yet Stendhal, Chateaubriand, and Vigny went out in society a great deal.”110 Reynaldo, who had not at first appreciated his friend’s remarkable intelligence, now understood Proust’s genius and the transformation that had taken place in him through application of his gifts to hard work and to his craft.

During the fall the relationship between Proust and Agostinelli reached a breaking point. On December 1 Agostinelli and Anna fled Proust’s apartment for Monte Carlo, where the secretary’s father lived.111 Distressed and angry, Proust appealed immediately to Albert Nahmias for help. Nahmias received a letter from Proust asking a “strange question.” Had Nahmias ever used private detectives to have anyone followed, and if so, could he give Proust their names and addresses? Stressing the urgency of the situation, Proust asked Nahmias to call him—not to talk about the matter openly on the telephone, of course, but perhaps Proust could ask Nahmias “cryptically about an address” or have him visit at once.112

Proust, mad with impatience and jealousy, began living scenes from a melodrama. He apparently did employ a private detective to keep informed of the whereabouts of Agostinelli and his father. Soon the desperate writer dispatched Nahmias to Monte Carlo with the purpose of bribing Agostinelli’s father into persuading his son to return to Paris. Proust knew that any direct appeal and offers to Agostinelli would meet with categorical refusals. Nor would Agostinelli agree to return if he knew that Proust had paid his father. Nahmias had to keep the negotiations secret.

For a period of five days Proust and his emissary exchanged long, cryptic telegrams under assumed names and using cover stories: one maintained the fiction that Nahmias was there on a mission regarding his own father; another involved a major, top secret stock market speculation. On Wednesday, December 3, at 9:46 P.M., Proust telegraphed Nahmias, under the young man’s real name, at the Hôtel Royal in Nice. He gave Nahmias the Monte Carlo address of Agostinelli’s father, Eugène, who ran a hotel at 19, rue des Moneghetti. Proust also knew that Eugène was to leave the following morning for Marseilles. Nahmias’s instructions were to offer a hefty monthly payment to Eugène if he could persuade Agostinelli to return immediately to Paris, without being told why, and to remain there until April. Above all, Nahmias must not offer money directly to Agostinelli (not named in Proust’s wire) because that would guarantee his refusal. And Nahmias must forcefully deny any suggestions on Agostinelli’s part that any incentives had been offered to his father.113 Proust signed the telegram Max Werth.

On December 5 Proust complained in a telegram about the extremely poor telephone connections and urged Nahmias instead to wire quickly and more often. In another telegram of 473 words, Proust expressed his concern about a wire he had sent to Nahmias that had remained unclaimed at the telegraph office. If Nahmias could not collect it, Proust, who always preferred appealing to the highest authorities, would have Prince Louis of Monaco retrieve it. On Saturday afternoon Proust sent a telegram suggesting that Nahmias could sweeten the offer. By Sunday, however, it was clear that the mission had failed and that Agostinelli would remain free. Proust instructed Nahmias to return to Paris and come see him immediately. After closing with love and gratitude, the sender did not sign the wire.

In the Search the Narrator becomes infatuated with the girl Albertine. Although such a character had been anticipated from the early stages of the novel, her name appears for the first time in drafts written in 1913. Proust began to adapt elements of his relationship with Agostinelli for Albertine. When Albertine flees the Narrator’s apartment, where he had attempted to keep her in loose confinement, the distraught lover sends Saint-Loup to Touraine to convince the girl’s guardians that she must return to Paris. Through Saint-Loup, the Narrator offers Albertine’s aunt, Mme Bontemps, thirty thousand francs for her husband’s political campaign if she can persuade Albertine to return.114 Saint-Loup’s mission also fails. Proust tried again to lure Agostinelli back to Paris in 1914.

In the weeks that followed publication of Swann’s Way, a number of reviews appeared by friends who were writers. Dreyfus, writing in the Figaro as the Masque de Fer, characterized the book as a “strong and beautiful work.”115 Cocteau, in Excelsior on November 23, called the book a masterpiece, writing that it “resembles nothing I know and reminds me of everything I admire.”116 Cocteau’s piece included a picture of Proust in the form of a bust on a pedestal.117 Lucien, in a long front-page article in the Figaro on November 27, praised Proust’s novel in terms that still hold. Among his many laudatory remarks, one singles out Proust’s profound analytical ability: “Never, I believe, has the analysis of everything that constitutes our existence been carried so far.” He called his friend a genius and his book a masterpiece.118

On December 8 Proust wrote Beaunier that he had written the remainder of his novel but that everything would have to be looked at again. He had just received a letter from the poet Francis Jammes, who praised Swann’s Way in terms that would delight any author. But Proust was still depressed. “At any other time,” he told Beaunier, “a letter like the one I just received from Jammes in which he says I am the equal of Shakespeare and Balzac (!!) would have made me so happy.” His misery did prevent him, he maintained, from being too saddened by articles like that of Chevassu, who accused him of extraordinary carelessness in composition and structure. But in fact such articles bothered Proust a great deal. Before ending the letter to Beaunier, he used the example of his character Vinteuil, prudish and dull but later discovered to be a musical genius: “Isn’t that composition?”

As though to counter the words of praise by Robert Dreyfus and Lucien Daudet, the editor of the Figaro’s literary supplement, Francis Chevassu, had written an unfavorable account of Swann’s Way in the December 8 issue. While acknowledging the “highly original” nature of the novel, he criticized it for lacking a plot and a distinct genre; the work resembled an autobiography with no structure. He ended by warning readers: “You must read M. Marcel Proust’s book slowly because it is dense.”119

After Swann’s Way had been on sale three weeks, Grasset, pleased overall with the reviews and with the sales, proposed a contract for translations and announced another printing, for which he offered to pay. He suggested a new contract giving Proust the standard 10 percent royalties. Proust made a counterproposal, stalling for time in order to consult Vaudoyer. Above all, Proust wanted to retain the ownership of his work and was uncertain about how to stipulate this in any future contract negotiation.120

On December 9 Grasset phoned Nicolas Cottin, “as though war had been declared,” to report that Paul Souday, an influential literary critic, had written a “detestable” review in the Temps.121 Souday had sarcastically reproached the author for the banality of his “childhood memoirs.” Instead of compelling events, “the matter of the story” comprised vacations and games in the park.122 Conceding that the contents of a book matter less than the writer’s talent, Souday claimed to quote Horace, who had severely criticized cases in which materiam superabat opus—the art surpassed the matter. Souday applied this reproach to the first 520 pages of Swann’s Way and wondered “how many libraries” the author would fill “if he decided to tell his life’s story?” Souday complained about the dense, obscure nature of so many pages filled with long sentences, and about the many typos. He had a helpful suggestion for publishers: they should hire some old academic, knowledgeable about grammar and syntax, to proofread copy. The reviewer admitted that the book was a “great original work” that displayed “a lot of talent,” but he deplored the lack of order and unity. Souday condemned what he considered the unmeasured, chaotic nature of Swann, while acknowledging that the novel did “contain precious elements out of which the author could have made an exquisite little book.” The reviewer had mixed feelings about the section called “Swann in Love”: “It was not positively boring, but somewhat banal, despite a certain abuse of crudities.” Later, when Proust became famous, Souday claimed to have discovered him.123

Rather than reply with a letter to the editor, Proust wrote directly to Souday, as he did to nearly every critic he felt had misjudged his work. Addressing the issue of grammatical errors and misprints, Proust admitted that they were too numerous, but fairly obvious. “My book may well reveal no talent; but it presupposes at least, or implies, sufficient culture to make it highly improbable that I should commit such crude mistakes as those you enumerate.” Proust pointed out a grammatical error in Souday’s article and observed that it did not make him conclude “M. Souday doesn’t know that the word sens is masculine.” Then he made a suggestion for the work schedule of Souday’s “old academic”: he could be used to check the sources of Souday’s Latin quotations. The hypothetical professor might point out that “it was not Horace who spoke of a work in which materiam superabat opus, but Ovid, and that the latter poet said it not critically but by way of praise.”124

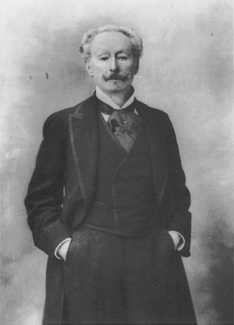

Charles Haas, 1895. The principal model for Charles Swann, Haas was a refined aristocrat associated with the court of Napoléon III. He was the only Jewish member of the exclusive Jockey Club. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

Madeleine Lemaire, 1891. The hostess of a bourgeois salon where artists and aristocrats mingled, she illustrated Proust’s first book, Pleasures and Days. Paul Nadar/ ©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

Anatole France, 1893. A distinguished writer whom Proust admired as a young man, France wrote the preface to Pleasures and Days. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

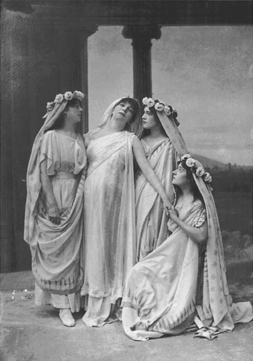

Sarah Bernhardt, 1893, in her most famous role, Racine’s Phèdre. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

Edgar Aubert, a young Swiss diplomat introduced to Proust by Robert de Billy.

Willie Heath, 1893, another young friend of Proust’s, who, like Edgar Aubert, died young. Paul Nadar/©Arch. Phot. Paris/CNMHS

Proust near the turn of the century. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France