Chapter 10

Whole-Body Training For Soccer

Throughout this book, the strength training focus has been on isolating a movement and the muscles involved in that movement. The strength training shelf of any commercial bookstore or library will display dozens of books that show how to train muscles in isolation. This concept ensures that every muscle is fully activated and will adapt to the new imposed demand.

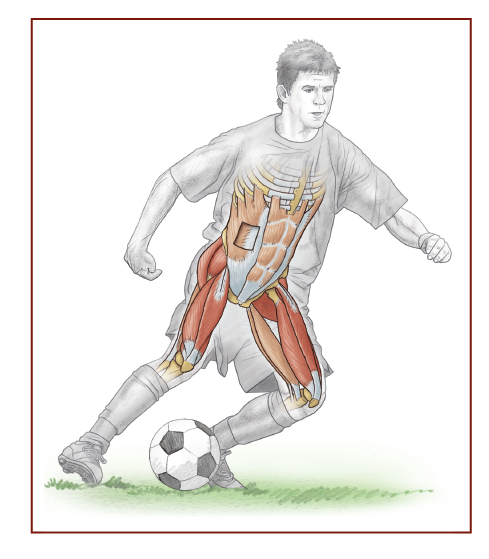

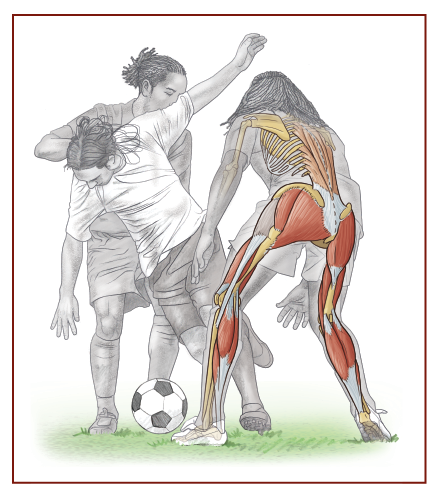

The next step is to incorporate the muscles to function as part of a whole system, sort of the athlete’s version of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. Athletic performance is not done in isolation. Rather, the whole of performance is greater than the result of the sum of the neuromuscular parts. Performance in sport is a combination of the technique required for that sport, the specific fitness (physical and psychological) for that sport, and the unique tactics for success. Some of these are planned and some are reactions to the opposition, but all evolve over time as advances force the sport to change. Any opportunity to involve multiple parts of the whole system will move the player closer to being able to execute the coach’s vision of the sport. This is especially crucial in team sports since the outcome is influenced by so many things—each individual player, the interactions of small and large group play, the style of play, the style of the opposition, the referee, the environment, the crowd, and more.

The options presented in this chapter have one common thread: They all require multiple joints, muscles, and muscle actions. No exercise is done in isolation. Coaches who have experience with or exposure to earlier training methods might recognize that similar field-based exercises formed the core of fitness circuits found in coaching books dating back to the 1960s and earlier.

Although players from the old country might remember similar exercises in their training programs, those programs were deficient in the basic training fundamentals: frequency, intensity, duration, and progression. They might have done comparable exercises but can’t recall doing things as frequently or as intensely or for as long as what is currently in vogue. And their training certainly was not periodized over a long competitive calendar. What is seen today is a reincorporation of earlier modes of training into modern training principles.

The goal of these and other whole-body activities is to prepare players for the strategic actions that will lead to success either in scoring or preventing goals. Those actions frequently require high power output for jumping or sprinting. Repetitive jumping is a plyometric activity, and various versions are used to take advantage of the stretch–shortening cycle that is known to improve power output not just in jumping but also in sprinting. If improvement in sprinting is a goal (and it should be), look at what track sprinters are doing and you will see plenty of exercises directed toward repetitive jumping.

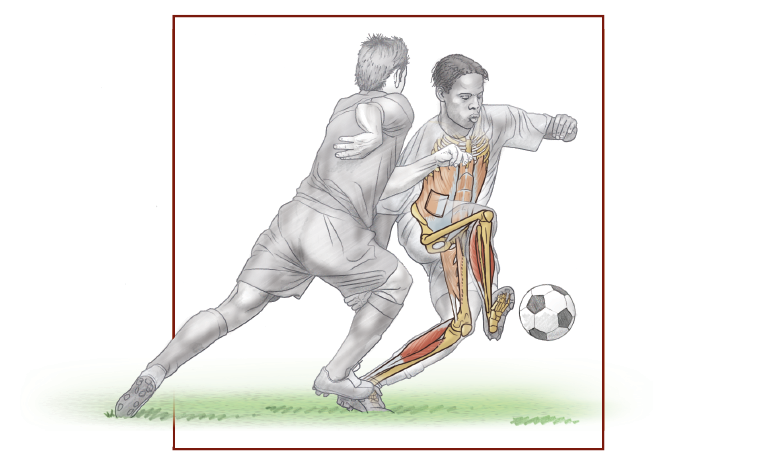

Incorporating whole-body training tools helps in coordinating the body during the random actions that occur every few seconds in a soccer game. Players will jump, hop, skip, leap, and cut at a moment’s notice, often without any conscious thought at the time to the action or reaction. Although it is difficult to plan training to mimic what actually happens when facing a real opponent (as opposed to a teammate in training), it is not difficult to prepare each player’s neuromuscular system to be ready to make sudden reactions to unforeseen circumstances during a match. And it’s the responsibility of the coach to make sure each player is as prepared as possible. This is why it’s more the norm today to see players doing guided activities that on the surface appear unrelated to the game. These might involve benches, hoops, hurdles, speed ladders, and other tools of the trade that will teach players to use their bodies efficiently with as few unnecessary movements as possible. Although the running form of a soccer player will rarely be mistaken for the smooth and efficient form of a sprinter, a comparison of soccer video clips from a few decades ago to today’s game should be proof enough that the training, coordination, and athleticism have advanced considerably.

Despite all the training advances of the past 25 years, none of them will produce the desired benefit if coaches and players fail to heed the lessons of experts in other supplementary aspects of performance. Consider the following:

• Research has shown that as little as 2 percent dehydration can lead to impaired performance. Don’t use the running clock in soccer as an excuse not to drink during a match. There are plenty of dead-ball opportunities to take a drink. On really hot days, the ref has the authority to stop play for a fluid break. A water break is part of the rules in numerous youth leagues during hot and humid conditions. Did you notice the water break in each half of the men’s gold medal game at the Beijing Olympics?

• It has been reported that between 25 and 40 percent of soccer players are dehydrated before they even step on the field for training or competition because they have failed to adequately rehydrate after the previous day’s training or competition.

• Muscle requires fuel, and the primary fuel for a sport such as soccer is carbohydrate. Restricting carbohydrate will only hinder performance. Players who enter the game with a less than optimal tank of fuel will walk more and run less, especially late in the match when most goals are scored. For some reason, team sport athletes are not as conscientious about their food selections as individual sport athletes are.

• Injuries increase with time in each half, suggesting a fitness component to injury prevention. One aspect of injury prevention is to improve each player’s fitness. Players should arrive at camp with a reasonable fitness level so that the coach can safely raise the fitness of the players even further through directed preseason training. Many teams have a very dense competition schedule, making it hard to raise fitness further during the season. Those who try to improve fitness each week with too much high-intensity work during a match-dense season risk acute and overuse injury, poor performance, slow recovery, and the possibility of overtraining.

• Some reports suggest that less skilled players suffer more injuries than do more highly skilled players. Thus, another way to prevent injuries is to improve skill.

• Take the time to do a sound warm-up such as The 11+ outlined in chapter 2 (page 18). Tangible rewards should be realized when a warm-up is included as a regular component of training. There are no guarantees when it is done infrequently. Most coaches are good at planning a training session, but neglect guiding the team through a good warm-up.

• The most dangerous part of soccer is tackling. Research has shown that the most dangerous tackles involve jumping, leading with one or both feet with the studs exposed, and coming from the front or the side. (Head-to-head contact is also dangerous. See the next item.) A simple axiom to remember is bad things happen when you leave your feet. Players should stay on their feet and not imitate what they see in professional games.

• Don’t take head injury lightly. Head-to-head, elbow-to-head, ground-to-head, goalpost-to-head, or accidental ball-to-head impacts are dangerous. You cannot see a concussion like you can see a sprained ankle. A player who experiences one of these head contacts should be removed from the game immediately and not be allowed to resume play until everyone is sure about his safety. The best advice is: When in doubt, keep them out. In the United States, many states are following the lead of Washington state, passing laws requiring written medical clearance before a player is allowed to return from a concussion. Don’t mess around with head injuries. No game is that important.

• Exercise some common sense when it comes to training. For example, use age- appropriate balls. Older players shouldn’t train with younger players. The younger ones will get run over or hit with high-velocity passes and shots. Next, the best predictor of an injury is a history of an injury, so an injured player should be fully recovered before returning. An incompletely healed minor injury often precedes a far more serious injury. Be smart and stand on a chair or ladder to put up or take down nets. The combination of jumping, gravity, rings, and net hooks is an invitation to a pretty severe laceration. Finally, never allow anyone to climb on goals. There have been serious injuries and even deaths because kids were playing on unanchored goalposts.

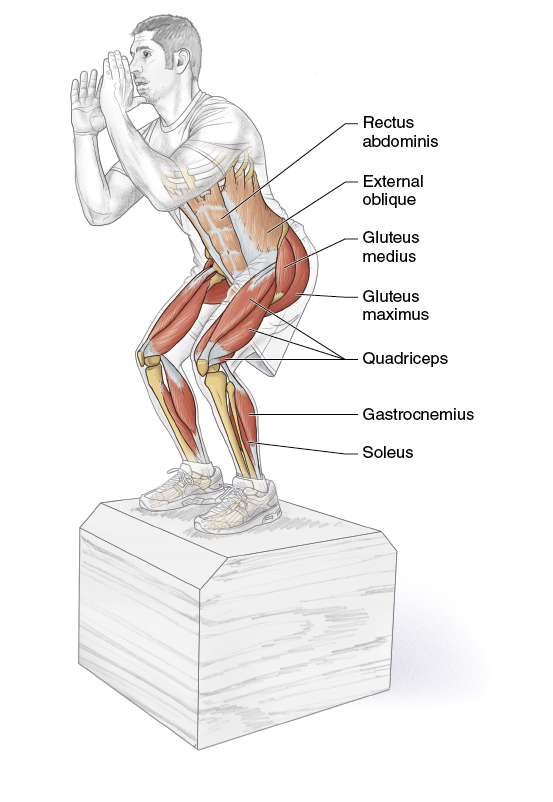

Knee Tuck Jump

Execution

1. Choose shoes with good cushioning, and jump on a forgiving surface.

2. Using a two-foot takeoff, jump as high you can. Bring your knees as close to your trunk as possible. Use the arms for balance during flight.

3. Land softly to absorb the impact, and then quickly take off again. Spend as little time on the ground as possible. This exercise is simply reciprocal vertical jumps.

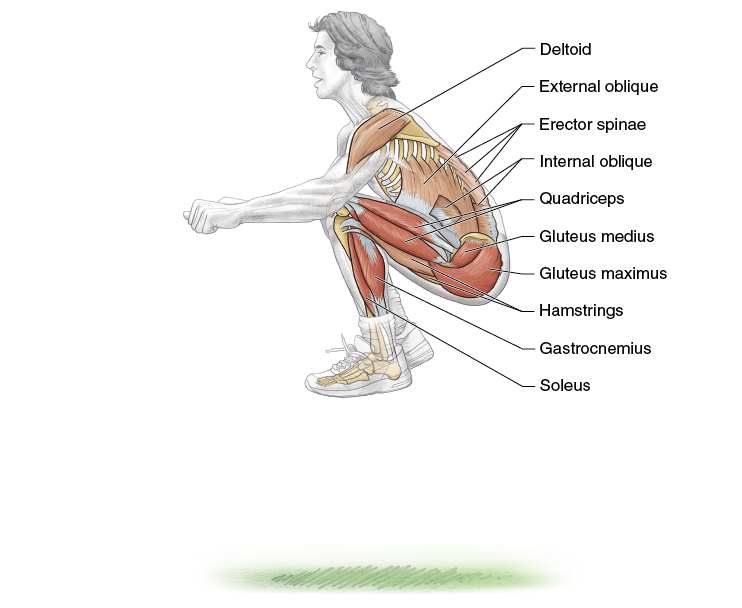

Muscles Involved

Primary: Quadriceps (vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, rectus femoris), gastrocnemius, soleus, gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, hip flexors (psoas major and minor, iliacus, rectus femoris, sartorius)

Secondary: Abdominal core (external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, rectus abdominis), erector spinae, hamstrings (biceps femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus), deltoid

Soccer Focus

Most books state that soccer is an endurance activity. With a 90-minute running clock (even though the ball is in play for only 70 minutes at most) and no stoppages, the game does have a significant endurance component. But games are won and lost by high-power bursts of activity—executing a short 10- to 20-yard (10 to 20 m) dash to the ball or outjumping an opponent for a corner, for example. Although these opportunities do not occur very frequently, players need to be ready when the time comes to execute high power output multiple times during a match. Many exercises train for high power output. Some involve an apparatus, and others are deceptively simple but very effective. Other exercises in this book involve jumping. Performing this exercise effectively requires you to jump as high as you can, pull your thighs up to your trunk, and then land softly and quietly. One jump is tough enough, but multiple jumps are very challenging. As you develop more power, you will find yourself jumping higher with each jump. As your legs develop local endurance, you will find yourself able to do more repetitions. Perform this exercise sparingly, when you have two or more days to recover before the coming match.

Repetitive Jump

Execution

1. Stand facing or right beside the touchline or end line on the pitch.

2. Using a two-foot takeoff, jump back and forth or laterally just barely across the line.

3. Upon ground contact, jump back across the line as quickly as possible. This movement is very rapid, with little flight time and minimal ground-contact time.

4. Rather than count the number of ground contacts, do these jumps as rapidly as possible for a defined number of seconds, adding time as fitness improves.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Gastrocnemius, soleus

Secondary: Abdominal core, erector spinae, adductors (adductor longus, adductor magnus, adductor brevis, pectineus, gracilis)

Soccer Focus

Endurance, power, speed, agility—soccer requires virtually every aspect along the spectrum of fitness. Fast footwork is quickly becoming a part of skill training programs. You are asked to do a wide range of activities with as many ball contacts as possible in a short period of time. The player who has done these exercises knows that the physical demands of fast footwork training can be very tiring. Short, rapid touches in a very short time tax the ability of the body to produce energy rapidly. Exercises performed as fast as possible in a confined space prepare you for this kind of work.

Variations

This exercise simply takes you back and forth across a line on the ground. You can think up any number of variations such as traveling up and down the line; performing two touches on each side of the line; or imagining a shape on the ground and touching each corner, forward and back, adding a half spin. Use your imagination; just remember the keys—minimal flight and ground time. Increase the duration as fitness improves. You will be surprised at how fast you see improvements.

Depth Jump

Execution

1. Choose a low box, about 12 inches (30 cm) tall.

2. Stand on the box with your legs about shoulder-width apart, hands and arms at your sides.

3. Step straight off the box. Land on both feet at the same time, bringing your hands up in front of you.

4. Absorb the impact of the landing by bending at the ankles, knees, and hips, sticking the landing so there are no adjustments to the impact.

5. Return to the box and repeat.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Hip flexors, quadriceps, gastrocnemius, soleus, adductors

Secondary: Erector spinae, abdominal core

Soccer Focus

Injury prevention is a theme of this book. Prevent injuries to keep playing and improve your game. At the core of injury prevention is neuromuscular control of the knees and the surrounding joints such as the ankles, hips, and trunk during demanding activities such as landing from a jump or cutting to change direction. Your goal for this exercise is to control the impact and not allow the knees to wobble right or left when landing. In addition, it is important to begin absorbing impact at the ankle and to not let the trunk waver during landing. If either of these surrounding joints shifts inappropriately, the knee must adjust, and this adjustment could put the knee in a poor position that could cause damage. Your coach should watch you when you perform this exercise to make sure your form is correct. Remember, these are single landings. Do not try to jump after stepping off the box.

Variation

Rebound Depth Jump

This is more of an extension of the depth jump than it is a variation. After landing, immediately jump up to another bench of similar height. This changes the depth jump from a shock-absorbing eccentric exercise to a plyometric task.

Speed Skater Lunge

Execution

1. Stand with your legs about shoulder-width apart, with your hands on your hips or out to the sides for balance.

2. Keeping your trunk erect and straight, jump slightly and lunge to your right, landing on your right foot. Your left foot is off the ground, and you are balanced entirely on your right foot.

3. Pause briefly and repeat, jumping and lunging to your left.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, quadriceps

Secondary: Erector spinae, hamstrings, abdominal core

Soccer Focus

This really is a whole-body exercise because it requires the legs to propel the sideways lunge; the core to stabilize the trunk during takeoff, flight, and landing; and the arms and shoulders for balance. With time you will begin to notice improvements in lateral quickness and agility. During a match, you don’t do much conscious thinking about your movements. You may find yourself dribbling at speed when a defender you didn’t notice pops up to challenge you. In an instant, you plant a foot and lunge far in the opposite direction while redirecting the ball into your path. But you never actually think about the movement; it just happens. The pace of your play and the ability to veer quickly and decisively away from your opponent can be drastically improved with simple exercises such as this. You will soon see an increase in the distance of the lateral lunge and the stability of landing as strength and neuromuscular control improve.

Floor Wiper

Execution

1. Lie on your back, holding an unweighted barbell above your chest. Arms are straight.

2. Without moving the barbell, raise your straight legs up toward one end of the barbell.

3. Keeping your legs straight, lower them back to the floor.

4. Repeat, raising your legs to the opposite end of the barbell. Moving the legs right and left counts as one repetition.

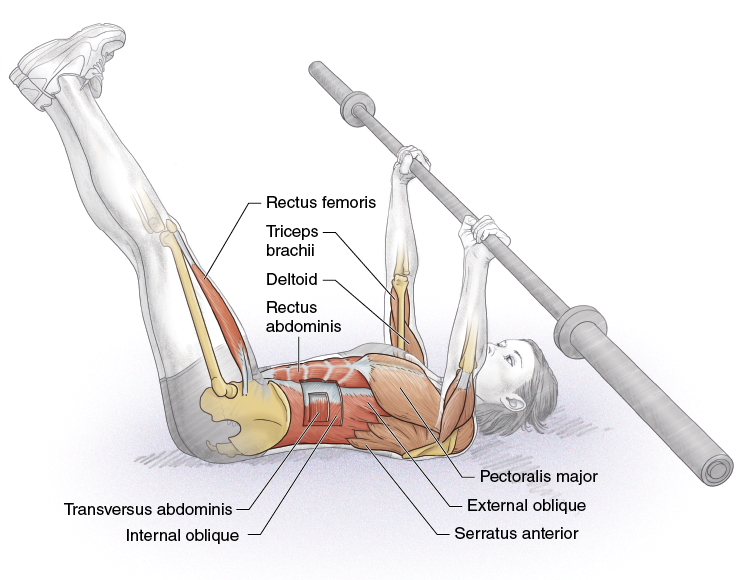

Muscles Involved

Primary: Abdominal core, rectus femoris, psoas major and minor, iliacus

Secondary: Sartorius, pectoralis major, triceps brachii, deltoid, serratus anterior

Soccer Focus

In the Soccer Focus section for the V-sit soccer ball pass (page 139), I mention a series of movies from the 1970s referred to as the Pepsi Pele movies. Within this excellent series of training films was a group of abdominal exercises that were part of a Brazilian circuit training protocol. This exercise is very similar, only instead of holding the ankles of a standing partner as the Brazilians did, you hold a barbell overhead and perform hip and trunk flexion combined with a little trunk rotation. Most of the abdominal exercises in the Pepsi Pele movies isolated the abs, but this exercise recruits multiple muscles of the core, making it a good bang for your exercise buck. Don’t take this exercise lightly. It is quite challenging, especially when you realize the hard part of the action restricts your breathing. Don’t forget that the bar stays overhead the entire time.

Variation

Floor Wiper With Dumbbells

This is the same exercise but with dumbbells. Holding a weight in each hand requires the arms and shoulders to balance each arm individually. Keep the arms overhead and the elbows extended as you perform the exercise as you would with a barbell.

Box Jump

Execution

1. Stand in front of a sturdy box—one that will not tip over—that is midshin to knee height.

2. Using a two-foot takeoff, jump high onto the box, landing on both feet. Don’t jump just high enough to land on the box. Jump higher so you are coming down on the box.

3. Jump back to your starting point, landing softly and quietly to absorb the force of the landing.

4. Repeat in a continuous, nonstop motion. Start with 5 to 10 seconds, and add time as fitness improves.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Quadriceps, gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gastrocnemius, soleus

Secondary: Abdominal core, erector spinae, hip flexors

Soccer Focus

Modern soccer is a mix of high-power-output activities surrounded by more endurance-oriented running. A sought-after trait is the desire and ability of each player to press everywhere on the field. Upon losing possession, the player, often with one or two teammates, will press the opponent on any number of levels (e.g., to immediately regain possession, to close down in order to occupy the opponent and keep the ball in front, to rapidly close down to force an errant pass, or to close down a player and delay forward movement, allowing teammates to recover). In each case, pressing the opponent requires a fast, controlled approach featuring a short-term period of very high power output. This kind of work is very intense, but it can have important and nearly immediate outcomes when the opponent makes a mistake and a teammate collects the ball. The challenge is to develop sufficient fitness in order to press, and press appropriately, when the need arises. Nearly every coach will say how hard it is to get a player to press when that player has lost possession of the ball. Part of this is frustration or disappointment at having lost possession, but it also may stem from a lack of fitness. Jumping exercises such as this require a very high power output that when used in combination with similar work on and off the ball should help put a team into the position of being very effective at pressing.

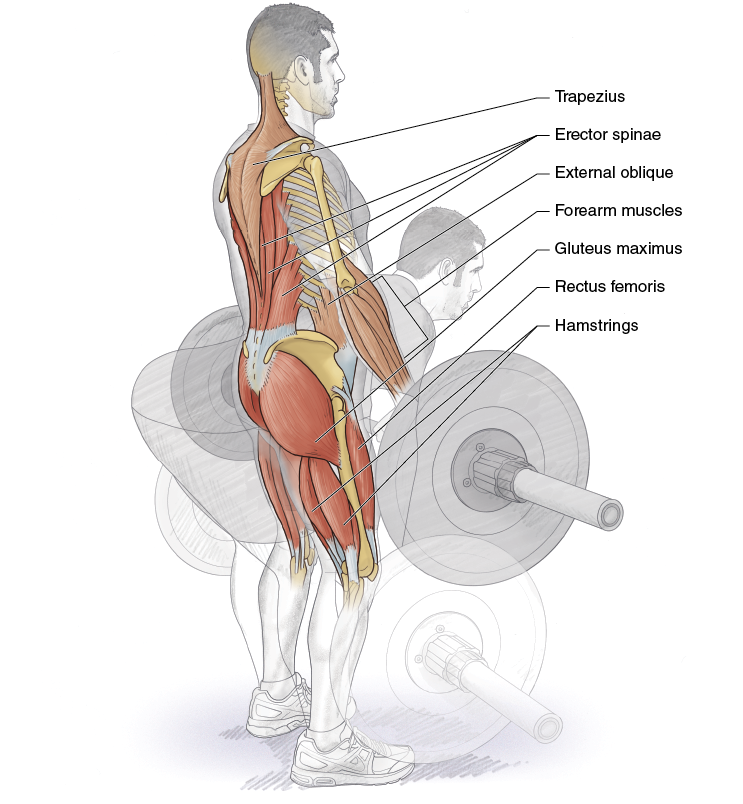

Romanian Deadlift

Execution

1. With the barbell on the floor, stand with your feet flat on the floor, shoulder-width apart or slightly less, and toes under the bar and pointed slightly out.

2. Move into a deep squat. With the arms straight, grasp the bar in an overhand grip, palms down. Your back should be flat or slightly arched. Pull your shoulders back and your chest forward.

3. Look forward and take a breath. Pushing through your heels and contracting your quadriceps and gluteals, pull the weight off the floor. Keep your back flat and the bar close. Stand erect, but don’t lock your knees. Exhale.

4. Inhale and slowly lower the bar by returning to the starting position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Erector spinae, rectus femoris, gluteus maximus, hamstrings

Secondary: Scapular stabilizers (such as trapezius), rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, forearm muscles (mostly wrist and finger flexors including flexor carpi radialis and ulnaris, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus, and flexor pollicis longus), vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius

Soccer Focus

The deadlift is a whole-body exercise found in nearly every training manual across the sporting spectrum. It demands power output from the legs, hips, trunk, and back. If you have never done this lift before, you may think it looks easy, but the use of a barbell increases its complexity by making a smooth motion more difficult. It is a good idea to get some personal instruction to ensure you are doing this lift correctly and safely. Rounding the back during the lift exposes the intervertebral discs to possible herniation, so keep your head up. Looking at the bar leads to a rounded back. Also, do not try to flex the forearms during this lift because it can place unnecessary strain on the biceps. Posture is the key. Don’t take any shortcuts with the deadlift.