CHAPTER TWO

The Iceberg Ahead

NOW FOR THE BAD NEWS. Promises to provide income for the elderly and health benefits for all Americans carry staggering prospective costs. These promises made by federal, state, and local governments and by private enterprises may generate costs that simply cannot be borne. The challenge is to find a way to fulfill the essence of these promises while reining in their future costs to manageable proportions. That is a tall order, and the process of reform has just begun. As Robert Frost put it in his “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”:

…I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep…

Many well-informed, expert analysts have made projections of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid spending. All have come to essentially the same conclusions, even though many different forecasts can be generated by alternative assumptions. The message, in study after study, is that current programs will create costs that are unsustainable.

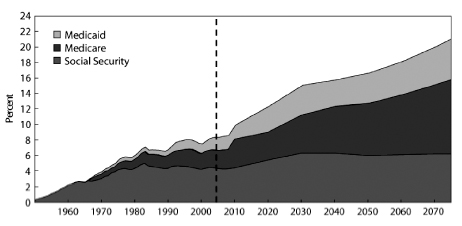

Chart 2.1 Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid Outlays as a Percentage of GDP, Fiscal Years 1950–2075

Economists Rudolph Penner and Eugene Steuerle, in “Budget Crisis at the Door,” published estimates of entitlement costs in 2003.1 Penner was the director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Steuerle was a high-level Treasury official, so they know what they are talking about. Their projections, shown in chart 2.1, reveal that federal spending on these programs, if they remain in their present form, will be in the range of 15 percent of the GDP twenty years from now and will represent more than 20 percent of GDP within seventy years. To put these estimates in perspective, the entire federal budget currently consumes about 20 percent of GDP.

This general picture is broadly confirmed by the 2007 annual reports of the Social Security and Medicare trustees and by projections using different assumptions made by the CBO, published in December 2005. These projections envision that:

- Under the intermediate spending path, Medicare’s costs would grow from 2.7 percent of GDP today to 8.6 percent in 2050. Total federal costs for Medicare and Medicaid combined would climb from 4.2 percent of GDP in 2005 to 12.6 percent in 2050.

- The higher-spending path, in which the assumed rate of excess cost growth for health care of 2.5 percentage points is slightly lower than the long-term historical average, results in future costs that are seemingly unsustainable. Federal costs for Medicare and Medicaid as a percentage of GDP would nearly double—to 8.1 percent—in 2020 and reach 21.9 percent in 2050.2

The projections of the Social Security trustees are no more reassuring. In 2007 the board said that Social Security expenditures will exceed dedicated tax revenue in 2017.3 They further said that the system’s unfunded liability over a 75-year window is $4.7 trillion.4

John Goodman, the president of the National Center for Policy Analysis, in testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee in 2005, presented a similar outlook. He concluded:

In just 15 years, the federal government will have to raise taxes, reduce other spending or borrow $761 billion to keep its promises to America’s senior citizens. As the years pass, the size of the deficits will continue to grow. Without changes in worker payroll tax rates or senior citizen benefits, the shortfall in Social Security and Medicare revenues compared to promised benefits will top more than $2 trillion in 2030,$4 trillion in 2040, and $7 trillion in 2050.5

The chorus of warnings continues. In his January 2007 testimony to the Senate Budget Committee, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke stated, “The longer we wait, the more severe, the more draconian, the more difficult the adjustment is going to be.”6

Recognition that the costs of entitlement programs are growing rapidly and are projected to eat up the entire federal budget is neither controversial nor new. In 1993, President Clinton created the Bipartisan Commission on Entitlement and Tax Reform. Chaired by Senator J. Robert Kerrey (Democrat from Nebraska) and Senator John Danforth (Republican from Missouri) and composed of members from both sides of the aisle, the commission projected that under 1994 law, entitlement spending in addition to the federal employee retirement system would consume the entire federal budget by 2030. Fortunately it appears that the commission’s projection will not materialize quite so soon, but the growth rate has merely been trimmed, thereby postponing, but not diminishing, the fiscal crisis.

From 1946 to 2005, federal revenues averaged just under 18.1 percent of GDP and never exceeded 21 percent.7 At the height of World War II, federal revenues as a percent of GDP were under 21 percent. In fact, the only other time federal revenues approached 21 percent of GDP was in the late years of the Clinton administration.8 These numbers should make it clear that the fiscal imbalance created by the growth of the large federal entitlement programs is a problem that must be addressed by changing the structures of the programs. If Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security were to grow as projected, they would require levels of taxation dramatically higher than any seen before. If the CBO’s high-cost assumptions were to become reality, federal tax revenue as a percentage of GDP would have to double in order to produce a balanced budget. Of course such high tax rates would not be a solution. On the contrary, they would ruin the economy.

These spending projections call for sober consideration. They can be tweaked, and assumptions can be changed, but the result will always be spending far, far in excess of any precedent in U.S. history. The message is that changes are necessary, not optional, and there is an urgent need to put them into effect. For example, present payroll tax revenues, presumably dedicated to the Social Security system, will continue to outrun benefit payments for almost another decade, but this surplus is already starting to shrink and is being spent as though it were part of general revenues. The sooner these funds are used to cushion the change to a sustainable system, the easier the transition will be. And the sooner a sustainable system is in place, the more confidently potential beneficiaries can plan for their futures. Every year of delay is an opportunity lost.

State and City Promises

The all-too-real problem of funding pension promises made by both state and local governments is broadly discernable, but the cost of health promises is just now beginning to surface. The Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) has published new rules governing accounting practices for health benefits for retirees. These rules require state and local governments to switch to accrual-based accounting, in which the present value of promises for the future must be publicly acknowledged, bringing pressure to show how these costs are to be financed. This accounting method more accurately reflects long-term liabilities, but local governments have generally used pay-as-you-go accounting, meaning they acknowledge the costs only as they actually pay the benefits. The result is that they mask their future financial liabilities.

As the snow is cleared from Robert Frost’s woods, more promises that have simply staggering costs will be revealed. The following examples hint at the seriousness of the problem.

Maryland, which until recently used pay-as-you-go accounting, provides some of the most generous health benefits in the nation to its retired state employees. To comply with the new GASB rules, the Maryland Department of Budget and Management commissioned a study to calculate the magnitude of its unfunded liability. The answer: $20 billion, or nearly double Maryland’s annual general fund budget.9 To prefund its liability over a thirty-year window, the state would have to contribute $1.9 billion each year, or approximately $340 per resident.

New Jersey is another state in deep trouble. As reported in the New York Times on July 25, 2007, unfunded promises of health care to New Jersey government retirees are now estimated to cost $58 billion, an amount nearly twice the size of the state’s debt.10

The GASB rule change also led the Los Angeles Unified School District to commission a study that found an estimated $5 billion unfunded liability for retiree health care.11 To fund this liability fully, the district would have to deposit $500 million, approximately 8 percent of the district’s overall budget, into the bank each year for the next thirty years.

State and local governments have made generous promises of retirement benefits to their employees, but many of these governments have neither set aside funds to pay these benefits nor properly accounted for them. An extreme example of unrealistic promises is found in San Diego. Among the many mistakes it made, San Diego raised retirement benefits for city employees in 2002, underfunded the system, and hid what was going on. By 2005 the city had a full-blown scandal on its hands, with a $1.4 billion unfunded pension liability and, once retiree health benefits were factored in, more than $2 billion in total liabilities.12 The fallout from the scandal included the resignation of the mayor and a number of other top officials as well as a federal criminal probe.13

Promises are all too easy to make when the responsibility for paying them falls to someone else at some time in the distant future. New York City leads the pack in this practice. Its pension system is so generous that the pension accrual of city firefighters would require a contribution of an additional 60 percent of their pay. Unfortunately, New York has followed questionable actuarial assumptions and fooled itself into thinking it was completely solvent. Its chief actuary, Robert C. North, says the official numbers are “meaningless.” He thinks that New York is approximately $49 billion in the hole on its pension funds, an amount equal to the city’s publicly disclosed outstanding debt.14

San Diego and New York may be the most egregious examples, but generous, underfunded government pension plans appear to be the norm. To put it simply, government employees want raises, and lawmakers want votes, but lawmakers do not want to pay salary increases out of the current year’s budget. The solution? Raise pensions, the costs of which do not show up in pay-as-you-go accounting. Lawmakers—and not just those at the local and state levels—should not make promises that will have to be paid for by future generations. If they cannot fund the promises, they should not make them. Accrual accounting will help dramatize the importance of that rule.

So the cost to the federal government of entitlement programs is only part of the iceberg. In varying degrees, states match federal spending on Medicaid. Because they do not have the luxury of running deficits and because the costs of their entitlement promises are now rising, they are currently feeling the pain of a squeeze on budgets, with commensurate pressure on spending in other vital areas. For example, in 2003, twenty-one states spent more on Medicaid than on K–12 education.15 States have also made large pension commitments to their employees, typically through defined benefit programs.16 Funding for these programs is usually in place but is typically inadequate for the prospective costs. Many big cities and small towns also have pension and health care promises to keep.

Insuring Private Commitments

Private employers are confronted by many of the same problems that governments face. They too made promises in the form of defined benefit retirement systems and health programs that place heavy burdens on their current and future cash flows. Some of these promises will become obligations of the federal government. This is because the promises of private defined benefit pension plans are partially backed by the federal government’s Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC). The PBGC collects premiums from private companies and partially insures their pension plans. Insurance payments to the PBGC have not kept pace with pension plan defaults as companies in bankruptcy, such as United Airlines, have turned their programs and the inadequate funding for them over to the government’s guaranty system, which is now woefully underfunded.

In many ways, the corporate health care picture is even more out of control than its pension system. Companies have made promises based on their predicted ability to fund them in the future. However, older companies, in particular, now have large numbers of retirees, and the unfunded costs of their pension and health care systems are crippling, especially in a globally competitive environment. Before the recent buyout of their obligations, it is estimated that General Motors’ health care commitments to its retirees cost the company $1,500 per car.17 GM faces vigorous competition from such companies as Toyota and Honda, which have no comparable cost overhang.

Pulling private and government programs together, we see that health care spending in the United States has risen dramatically, from 5.2 percent of GDP in 1960 to 16 percent by 2006, and is expected to reach 18.7 percent of GDP by 2014.18 The portion of these expenditures paid for by the federal government has increased steadily from 11.3 percent in 1965 to 34 percent in 2006.19 In addition, the federal and state governments lost approximately $200 billion in revenue in 2006 because of their failure to classify health insurance premiums as taxable income.20

Clearly the choice is not between taking action and maintaining the status quo. Change is necessary. The urgent question is how to implement changes that will bring costs under control while providing income for the elderly and a comprehensive, high-quality health care system.