CHAPTER FIVE

Principles for

Reforming

Social Security

SOCIAL SECURITY is one of the federal government’s most successful programs. It is administered efficiently, and, by and large, it has delivered on its promises. It provides a safety net of retirement income to the nation’s elderly and has been so successful in that respect that the poverty rate among the elderly is now lower than among the nonelderly. This wasn’t the case before Social Security became large and important in the 1950s and 1960s. Many people now rely on Social Security to provide their basic retirement income.

As we have seen, there is one big problem with Social Security. More promises have been made for the future than the current system has the means to deliver. To put it bluntly, the system is insolvent over the long run—and not by just a little bit. This opinion is not ours alone; it is the opinion of essentially everyone who has closely examined Social Security. The Clinton administration reached this conclusion, as did the subsequent Bush administration. The insolvency of Social Security is not a secret, nor is it controversial. In fact, the annual statements now mailed to every Social Security participant carry this warning in boldface type: “Your estimated benefits are based on current law. Congress has made changes to the law in the past and can do so at any time. The law governing benefit amounts may change because, by 2040, the payroll taxes collected will be enough to pay only about 74 percent of scheduled benefits.” This official warning is sobering for today’s middle-aged and young people who will still be participating in Social Security in 2040, and the trouble is that the solvency problem will surface long before then.

The focus of this chapter and the next is what to do about this serious problem. One thing should be clear at the outset: Doing nothing—more or less the sum of the policy actions of the last twenty years—is not an option. The problem won’t go away by ignoring it. A sudden 26 percent across-the-board benefit cut, which is what the boldface warning hints at, would be terrible policy and cause serious problems for both retirees and workers. Remember the famous football coach, George Allen, who, when asked if he was building for the future, said, “The future is now.” Well, now is the time to get going on reform of the Social Security system.

We shall first describe how Social Security works. Before evaluating various alternatives for reform, it helps to understand how the system operates now. We’ll pay particular attention to whether benefit levels for workers of today and the future can increase as fast as wages or prices. This may sound like a technical distinction, but it makes a critical difference in terms of the solvency of the entire program.

Then we shall lay out some principles for reform. The obvious objective is to fix the system—to overcome the solvency problem so that the system can bring its promises and resources in line with each other. It doesn’t make any sense to send out statements that inform participants of their promised benefits and then warn them that the promises can’t be kept. In addition to basic solvency, we shall come up with a number of other important principles for reform.

Finally, in the next chapter we shall present specific proposals for reforming the system. Solvency can be achieved. In fact, the problem can be solved in several different ways. We shall present plans that we think are the best and most practical, but we’ll also describe several alternative solutions, any one of which would be infinitely better than doing nothing. There really are no excuses for not fixing Social Security. The problem is well understood, and there is wide argument on the menu of choices available to fix it.

The Nuts and Bolts of Social Security Today

The basic structure of Social Security has not changed since at least the 1983 Greenspan reforms. The focus here is on the retirement program within Social Security, although its survivor and disability benefits are also important. The reform proposals subsequently leave these other parts of the program intact.

The Tax Side

The tax side of the Social Security program is simple. As of 2008, Social Security is financed with a 6.2 percent tax on earnings up to $102,000 per year. Both employee and employer pay this 6.2 percent tax, so the total tax on the first $102,000 of earnings is 12.4 percent. For example, if Sharon made $40,000 in wages in 2008, her payment of Social Security taxes would have been 6.2 percent of $40,000, or $2,480. Her employer would have deducted $2,480 from her checks, leaving her with $37,520, net of Social Security taxes.1 Actually, her employer would have had to forward $4,960 to Social Security—the $2,480 deducted from her paychecks as well as the 6.2 percent employer’s tax. Economists believe that workers such as Sharon actually bear the entire burden of the 12.4 percent tax. If it were not for Social Security, she would have made $42,480 (the amount her employment actually costs her employer) instead of $37,520. The accurate way to look at Sharon’s situation, therefore, is that she effectively paid $4,960 in Social Security payroll taxes. To put this figure into further perspective, her federal personal income tax bill would almost certainly be less than that. If she were single with no dependents, had no other income, and relied on the standard deduction, her federal income tax bill would have been $4,451. Like the majority of American workers, she would have paid more in Social Security taxes than in federal income taxes.

These Social Security payroll tax rates have been in effect since 1990 and are not scheduled to change, according to current legislation. However, the maximum level of earnings subject to the full set of taxes, $102,000 for 2008, is raised annually to reflect increases in average wages. The payroll tax has risen dramatically over the years as the program has been scaled up. For instance, the maximum total Social Security tax in 1960 was 6 percent of $4,800, or $288, instead of the 2008 maximum of 12.4 percent of $102,000, or $12,648. The maximum payroll tax payments have gone up forty-four-fold since 1960, while prices have gone up about seven-fold. Any way you look at it, the program has gotten much larger and more expensive.

The Benefit Side

Social Security’s retirement benefit structure is much more complicated than the tax structure, and several steps are taken to determine a retiree’s initial monthly benefit. First, an individual’s record of covered, or taxed, earnings is assembled. Each year of earnings is then multiplied by an average wage index factor. The purpose is to make comparable each year of earnings in an individual’s career. For example, if wages in the economy increased by a factor of 6.08 between the year a worker was age twenty-five and the year he was sixty, his earnings at age twenty-five would be multiplied by 6.08 before being compared with his earnings at sixty.

After all wages earned before age sixty are indexed, the next step is to calculate the retiree’s average indexed lifetime earnings. This is Social Security’s measure of how much a worker earned, on average, in his or her career. First, the highest thirty-five years of indexed earnings—the only years that count—must be identified. If an individual worked for forty-five years, the taxes he or she paid in the ten years with the lowest indexed earnings would not count toward retirement benefits. If the retiree did not work for thirty-five years, some of his or her highest thirty-five years of indexed earnings are simply entered as zeros. Having identified the highest thirty-five years of indexed earnings, Social Security simply adds them up and divides by the number of months in thirty-five years (420). The result is the worker’s average indexed monthly earnings, which Social Security refers to as the worker’s AIME.2

Once the average indexed monthly earnings figure has been computed, we are more than halfway toward figuring out a potential retiree’s initial monthly benefit. The next step is to compute the standard monthly benefit amount (termed the primary insurance amount, or PIA), the amount a single retiree would receive per month in initial benefits if he or she retired at the full retirement age. The full retirement age has recently increased to sixty-six for those born from 1943 to 1954. It advances two months per birth year for those born between 1955 and 1960, so for those born in 1960 and later, the full retirement age will be sixty-seven.

The formula that translates the average indexed monthly earnings to the standard monthly benefit amount is progressive; in other words, it offers a more generous conversion for those with low average career earnings than for those with high average earnings. However, when examined on a lifetime basis, the program is less progressive than it appears. The primary reason is that people with low earnings tend to have shorter lives than those with higher incomes. They have a lower chance of collecting any retirement benefits and tend to receive them for shorter intervals once those benefits have commenced.

The final step is to calculate an individual’s benefit relative to the benefit if he or she retired at the full retirement age. If an individual retires and claims benefits earlier, his or her monthly benefits will be permanently reduced. On the other hand, for those who begin receiving benefits later than the full retirement age, benefits will be permanently increased, depending on the exact retirement month. The penalty for early retirement and the bonus for late retirement reflect the fact that early retirees will collect benefits longer than late retirees. Once initial benefits have been determined, future benefits are increased once a year by a factor determined by price inflation.

There are seemingly endless complications to the full range of benefit calculations, such as those for widows and widowers, but you now have the big picture. Remember one important thing, however: The taxes described here will not generate enough revenue in the future to pay the benefits if they are determined in the manner just explained. Something will have to give, and it has to be either the benefit determination or the taxes. Nothing else will bring about solvency.

Wage Indexing Versus Price Indexing

A number of reform or solvency proposals depend on the way early-and later-career earnings are made comparable. The present system of wage indexing was introduced into the Social Security system in 1977. The intention was to raise benefits automatically rather than on an ad hoc basis when politicians got around to it (almost always in election years). The automatic feature is a good idea, but tying the increases in initial monthly benefits to wages has proved unsustainable in the long run. It is the wage indexing that causes Social Security’s aggregate benefits to grow faster than its tax revenues. This was foreseen in the report of the officially appointed Consultant Panel on Social Security, published in August 1976: “The price-indexing method produces expenditures that are relatively level as a percentage of taxable payroll. But the wage-indexing method produces expenditures that require substantially greater tax payments from future generations of workers.” The short explanation is that, over time, the Social Security tax base increases with wage growth plus labor force growth, while Social Security retirement benefits under current law increase with wage growth plus beneficiary growth plus growth in life expectancy. The length of retirement has been increasing but the number of years worked has not, so the system’s expenditures have grown and will continue to grow faster than revenue.3 For a business, this would be a ticket to bankruptcy.

In 1976 the Consultant Panel on Social Security correctly predicted that wage indexing would cause insolvency or perpetual shortfalls. Ever since wage indexing was introduced in the United States, twenty-eight out of thirty annual reports by Social Security’s trustees have described the system as fiscally insolvent in the long run.

Indexing the automatic increases to price levels rather than wage levels may sound like a small change, but it could have large consequences, as we will discuss in chapter 6. The underlying insight is that, in general, wages go up faster than prices because of productivity increases. If prices were used rather than wages, the rate of increase in future initial monthly benefits would be lower. Still, the price indexing method would preserve the real value of benefits.

Table 5.1 shows the initial monthly benefits for three hypothetical individuals who reached the age of sixty-two in 2007. The middle column shows benefits under the current law. The progressivity of the benefit formula is illustrated in that the monthly benefits for someone whose earnings were always at the national average are only 56 percent higher (rather than twice as high) as the benefits for someone who always earned half as much. The right-hand column shows what the benefits would be today if the Social Security Administration had adopted price indexing reform at the time of the Greenspan Commission in 1983. The numbers in this column could be called “what if” numbers. The table shows that benefits would be 16 to 19 percent lower for someone reaching the age of sixty-two in 2007 if the government had switched to price indexing in 1984. Current retirees might consider themselves lucky, but if that switch had been made, Social Security would be completely solvent today rather than being several trillion dollars short.

Table 5.1 Primary Insurance Amounts If Price Indexing Had Been Adopted in 1983

CURRENT SYSTEM OF WAGE INDEXING |

SYSTEM OF PRICE INDEXING | |

Individual earns half of national average wage for thirty-five years |

$888 |

$727 |

Individual earns national average wage for thirty-five years |

$1,383 |

$1,163 |

Individual earns more than payroll tax cutoff for thirty-five years |

$2,120 |

$1,716 |

Western Europe, where an aging population and other demographic developments create more immediate pressures than in the United States, has largely been forced to abandon wage indexing. The United Kingdom took significant action earlier than most countries and, in 1980, switched from wage indexing to price indexing for its basic state pension.4 In 1992 and 1993, Italy and France, respectively, passed legislation to switch from wage indexing to price indexing.5 Germany introduced a “sustainability factor” in the benefit calculations for its state pensions in 2004.6 Essentially, the German government will pay benefits only out of the money that is available, and there will be less available than would be needed to pay wage-indexed benefits.

With this background on how the current system works and the need for change to achieve solvency, we propose five general principles for any economically and politically acceptable reform proposal.

- 1. Those individuals nearing retirement age should be guaranteed benefits as provided under current law.

This guarantee is widely agreed upon. It would apply to all who are fifty-five years of age or older because they have too little time to make alternative plans. As many in this age group count on Social Security, any change in the rules should be gradual and announced far in advance. Every serious proposal should protect those over fifty-five from changes in benefits. - 2. Low-income individuals should be protected, and the progressivity of Social Security should be maintained or even enhanced.

For 65 percent of beneficiaries, Social Security benefit payments provide more than half their total retirement income. For 21 percent of beneficiaries, Social Security is the only source of income. The safety net that Social Security provides in old age is substantial, and reform proposals should maintain and strengthen this safety net. Those who experience low lifetime earnings should not be made worse off than they are under the current law. - 3. The rate of growth of benefits must be contained.

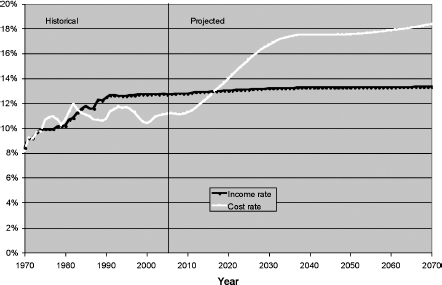

This issue is more complex but just as compelling as the two previous points. The Social Security program’s projected finances are such that the income it receives is a constant percentage of total payroll. However, benefits are projected to be an increasingly larger percentage of total payroll. Chart 5.1 illustrates this point. It shows the income and costs of Social Security as a percentage of the total covered payroll. The income rate consists mostly of the total payroll taxes received from employees and employers. The cost rate is the amount paid out to beneficiaries as a percentage of covered payroll. The shortfall of income relative to costs over the next seventy-five years gives a sense of the financial troubles of these programs. In 2006 this shortfall of Social Security was estimated to be 2.02 percent of taxable payroll over the next seventy-five years.7

It is clear that the Greenspan Commission accomplished something important in 1983. Before that, from the mid-1970s to 1983, Social Security was running substantial deficits. In fact, by 1983 Social Security was on the verge of having to delay or reduce benefits. The system almost ran out of money. Then, with the reforms of Social Security in 1983, the system swung into surplus and has been in that situation ever since. But the surplus will begin to shrink dramatically in just a couple of years and will disappear completely by 2017. After that, the projections are for deficits as far as the eye can see. But, it is even worse than that: Not only is the cost rate higher than the income rate beginning in 2017, but the cost rate is increasing much more rapidly than the income rate. This means that tax increases alone will not solve the financial problems of Social Security. Increasing taxes is merely a temporary fix for a permanent problem. If tax rates in 2070 were increased to the projected cost rate of a little over 18 percent, with no other changes to benefits, the system would immediately step out of balance in 2071 because the benefits paid are projected to increase faster than the tax base. The only way to solve the problem is to adjust the growth rate of costs by introducing changes that prevent the programs’ costs from growing more quickly than their tax bases (aggregate covered earnings). - 4. Individual retirement accounts should be considered.

Individual accounts have considerable merit as part of Social Security reform. They cannot cure the solvency problem—in fact, they are almost always solvency neutral, neither worsening nor helping with that issue—but they certainly can help increase the saving rate in a country that needs more saving. They would encourage or even require citizens to participate in American capitalism. This is sometimes called the ownership advantage. And the return on private U.S. markets has historically been very attractive.

Many alternatives exist for the size and structure of private accounts. They could be funded in whole or in part from a portion of the payroll taxes paid on behalf of an individual, with defined benefits reduced commensurably, a practice known as a carve-out. The alternative would be an addition to the payroll tax, called an add-on, as the source of funds. Our own view is that individual accounts, if adopted, should be substantial in size in order to justify the extra costs of setting up and administering the system. No doubt, investment choices would be limited to well-diversified options in order to control risk, and the allocation between equity and fixed income funds would change as an individual ages.

One advantage of individual accounts is that contributions to them are far less distorting than are payroll taxes. Even mandatory contributions to an individual account should not be considered as taxes. The money still belongs to the owner of the account, who typically has some control over how funds are invested and can either enjoy the proceeds in retirement or bequeath them to heirs. Another advantage of individual accounts is that they contain real assets, such as stocks and bonds. In addition, once the funds are identified as being owned by an individual, the likelihood that those funds could be spent as though they were general revenue, as are the current trust funds, would be minimal. - 5. Social Security should be flexible to adjust to future demographic and economic shifts.

Many of Social Security’s financial problems stem from a fundamentally positive fact: Life expectancies have increased dramatically, as shown in chapter 1, and are projected to continue to increase in the future. Nevertheless, mortality rates, fertility rates, and other demographic characteristics are difficult to predict with any amount of accuracy. In 1977, when wage indexing was introduced as a way to increase benefits automatically to maintain the standard of living of beneficiaries, the rate of price growth was higher than wage growth. Today that relationship has reversed. The Social Security system can adapt to many of these changes only with new legislation, so policy makers must regard the system as a work in progress and be ready to take action at appropriate times. Senators Dianne Feinstein and Pete Domenici introduced legislation along these lines in January 2007. They would have a commission appointed with the mandate to review the system continuously and recommend appropriate changes periodically. The legislation encourages Congress to move expeditiously on entitlement reform.

The following chapter presents reform plans that meet the general principles outlined above and promise to eliminate the long-run solvency problem. There is a menu of several possible solutions that would work. The challenge is to find the best set of adjustments to transform the present unsustainable program into a system that is sound and solvent.

Chart 5.1 Cost and Income Rates of Social Security