CHAPTER TEN

Medicare, Medicaid,

and Health Care

Reform

THE PRESENT SYSTEM of health care in the United States must be changed, for it produces rapidly escalating costs that threaten to rise to unsustainable levels. In fact, as described in the previous chapter, significant changes and reforms have already started to take place. But the problems are large, and the actions taken to date are too small. We have a mixed system that is half private, half public, heavily bureaucratized, and uneven in its coverage. Some parts of the system are breathtakingly good, but other parts require extensive changes.

There is an emerging consensus that Americans should have universal access to quality health care. We agree. A bold vision and a well-thought-out plan of action are needed to secure an efficient, effective, affordable health care system for this country. Alternative ways to achieve this goal are presented in this chapter, along with our own set of recommendations.

One alternative, consistently rejected by the American political process, is to go the way of Europe and Canada. Under their government-dominated systems, universal access is provided, bureaucracy reigns, rationing of health resources takes place by waiting lists, and European and Canadian patients have been known to use the United States as a safety valve.

Any appropriate U.S. alternative must meet certain goals. Drawing on points discussed in previous chapters, here are key criteria for an effective system that provides needed benefits and contains costs:

- Benefits should be attached to individuals because the U.S. labor force is mobile and employers come and go.

- Everyone should have reasonable access to benefits.

- A method of cost containment should be built into the system, with insurance companies and other providers of services subject to the pressures of competition.

- Systematic variations in the risk of health problems, such as the plain fact that risk rises with age, should be recognized.

We shall present a set of proposals that meet our basic criteria. These proposals will be best understood when placed against the background of four other ways of working toward the goals we have set out. To an important degree, we draw ideas from each of the alternatives.

The Friedman Plan

The late Milton Friedman, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976 and was certainly one of the greatest economists of the past century, set out his approach in “How to Cure Health Care,” published in the winter of 2001. At the time he wrote this article, Medical Savings Accounts were new and limited; nevertheless, he saw great potential in them when combined with universal catastrophic health insurance. Friedman proposed that the current Medicare and Medicaid systems change to a system in which participants would receive a major medical insurance policy with a high deductible and a specified deposit in a health savings account. Current participants would be given the option to continue with their present arrangement or to participate in the new system. He believed this arrangement would be less expensive and bureaucratic than the current fee-for-service system and that participants would prefer such plans because of the level of choice they afford. Friedman wrote: “It would be a way to voucherize Medicare and Medicaid…[enabling]…participants to spend their own money on themselves for routine medical care and medical problems, rather than having to go through HMOs and insurance companies, while at the same time providing protection against medical catastrophes.”1 He went on to describe a more radical reform that would provide catastrophic insurance coupled with health savings accounts for every family in the United States. He also favored ending the current tax exemption of employer-based health insurance and removing “the restrictive regulations that are now imposed on medical insurance—hard to justify with universal catastrophic insurance.”2

Friedman laid out a conceptual framework providing universal coverage that empowers consumers and focuses insurance on catastrophic risks. His call for a sweeping change in the system providing access to health care meets our criteria.

The Fuchs-Emanuel Plan

In a similar but more detailed fashion, Victor Fuchs, an emeritus professor at Stanford University who is widely considered one of the leading health economists in the country, and Ezekiel Emanuel, of the National Institutes of Health, have developed a comprehensive plan for universal health insurance through Friedman-like vouchers for all Americans.3 Their plan would enable individuals and families to choose from several privately offered basic health insurance plans with relatively low deductibles and copayments. Individuals could pay for additional services not covered under their basic plan or upgrade to premium insurance policies with their own after-tax money.

All the basic plans would offer benefits similar to those offered by large employers today and would provide adequate coverage for most people. A government board would determine the minimum coverage of the basic plans. The vouchers would be risk adjusted so that their value would reflect the age, gender, health history, and expected use of health services by each participant. All the basic health insurance plans would offer guaranteed enrollment and renewals for all Americans. Everyone would have a choice of plans, and everyone would have high-quality coverage.

Like Milton Friedman’s concept, the Fuchs-Emanuel plan would eliminate the tax exemption for employer-provided health insurance. With the issuance of universal vouchers and the removal of tax incentives for employment-based health insurance, it is likely that employers would quickly get out of the business of providing health insurance.

Under the Fuchs-Emanuel plan, Medicaid and other means-tested government health insurance programs would be replaced immediately by universal vouchers. Because the new program would cover everyone, there would be no reason to have separate programs for low-income individuals. On the other hand, Medicare would be phased out gradually. Current participants could remain on the traditional Medicare plan for the rest of their lives, but Medicare would not accept new enrollees. In the future, those turning sixty-five would simply continue with the universal voucher health insurance program. Ultimately there would be one program, with choice within the program, for everyone.

The Fuchs-Emanuel plan for universal vouchers would be funded by a new value-added tax, essentially a dedicated national sales tax, the revenues of which would be strictly devoted to the voucher plan. The advantage of dedicating the revenue source is that it links the benefits of the program to its costs. Proposals to enhance benefits would necessitate tax rate increases, so any proposal to expand the basic plans would require a debate about whether the extra benefits from the new proposal would justify the additional costs. General revenue financing, which is currently employed for Parts B and D of Medicare, allows politicians to avoid this tough question. Benefits, such as Medicare prescription drugs, have been added without identifying where the additional funds will come from. Fuchs and Emanuel argue that tax dedication would force better decision making. We agree, but we worry that the political process will find a way around this safeguard if it wants to. We also question the feasibility of combining massive reform of the health care system with a substantial change in the tax system. Either of these is a big undertaking.

Another feature of the Fuchs-Emanuel plan would be the establishment of an independent Institute for Technology and Outcomes Assessment. It would play a key role in providing the marketplace with unbiased information about the efficacy of various treatments, the services and treatments that should be included in universal coverage, and what should be left to choice. In order to have a system that empowers consumers with choice, consumers must have unbiased information on which to base their decisions. Fuchs and Emanuel propose that one-half of 1 percent of the revenues raised to support their system of universal vouchers be directed toward funding this institute.

The Fuchs-Emanuel plan would probably be no more expensive than the sum of our current system of employment-based health insurance (partly paid for by tax subsidies), separate programs for low-income individuals such as Medicaid, Medicare for the elderly, and emergency room treatment for the uninsured (paid for by taxpayers and the insured). But their plan would create more cost-conscious, informed consumers with a resultant pressure on costs.

Of course, employers do not provide free health insurance to their employees; wages and salaries are lowered by the compensation paid in the form of health benefits. If the Fuchs-Emanuel plan were adopted, companies would drop health coverage, but competition among employers would drive wages and salaries upward. Employers would still have to pay employees the marginal value of what they produced.

In addition, individual income tax rates could be lowered because of the elimination of Medicaid and the removal of the tax exemption for health insurance, which currently allows employers to provide part of their compensation to their employees tax free. Offsetting all this, of course, would be the burden of the new health insurance value-added tax. Therefore, taking everything into account, the cost of health care for the average American probably would be about the same as it is under the current system. However, the Fuchs-Emanuel plan would encourage greater competition and access to health information, and the government would be better able to predict and make provision for future costs by calculating the cost of vouchers.

The Cogan-Hubbard-Kessler Plan

A different approach has been put forward by economists John Cogan, Glenn Hubbard, and Daniel Kessler in Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Five Steps to a Better Health Care System.4 In this carefully written book, the authors set out their recommendations, which are designed to increase competitiveness in the health care market, improve the quality of information available to participants in the market, and improve the capacity of consumers to exercise effective choices. We include their ideas in our own recommendations.

The President George W. Bush Plan

Still another approach was put forward by President Bush in his 2007 State of the Union address. He proposed, as have Friedman and Fuchs-Emanuel, to fix one of the federal tax code’s most damaging and distorting—and most enduring—features, the tax exclusion for employer-provided health insurance.

Because health expenditures by an employer are not counted as compensation, health care purchased by the employer is not taxed, whereas health care purchased by an individual is taxed. This heavily favors health care expenditures by an employer over expenditures by an individual, and the more the employer spends, the larger the federal tax subsidy. This encourages expensive, low-deductible health plans and third-party payer systems that drive up the costs for everyone. The total value of the federal tax subsidy is now on the order of $200 billion a year.

Policy makers have long wanted to remove this tax exclusion but have considered the idea dead on arrival. Cogan, Kessler, and Hubbard write: “The best way to reverse this trend [toward low-deductible insurance] would be to revoke the tax preference. Unfortunately, as experience from the tax-reform debates of the 1980s showed, this solution appears politically infeasible.”5 Sometimes what appears infeasible actually may be possible. In an innovative way, President Bush has proposed a palatable replacement for the tax exclusion that is far more efficient economically.

The president’s proposal removes the tax exclusion from employment-based health expenditures while moving the tax subsidy to individuals. Specifically, his proposal would create a standard deduction for having health insurance and end the tax exclusion for employer-provided health insurance. The deduction would total $7,500 for an individual and $15,000 for a family. Importantly, the size of the deduction would depend not on the cost of the health insurance purchased but rather on demonstration that a suitable purchase had been made. An individual would get the same $7,500 deduction if he or she had a $10,000 health insurance plan with no deductibles or a $3,000 health insurance plan with high deductibles. An individual who wanted an expensive, low-deductible plan could still get one, but the decision would no longer be distorted by the tax code. To save money, consumers would likely opt for plans with higher deductibles and coinsurance. Health insurance would begin to resemble more closely all other types of insurance, and consumers would have a greater stake in the game.

The population in the two lowest income quintiles pays no income tax and therefore would not be able to use the deduction. If the president’s proposal were enacted, it would almost surely be accompanied by an equalizing tax credit for those who pay no taxes, provided on evidence of the purchase of suitable insurance. If this were done, then a wide swath of the U.S. population would be in control of purchasing their health insurance. The result would be something akin to the universal voucher system proposed by Friedman and Fuchs and Emanuel, as outlined above.

The president’s proposal is estimated to be revenue neutral with some shift in the overall benefit of the federal tax subsidy from those with the most generous insurance policies to those with more standard policies. If his proposal is adopted, we shall applaud and adjust our recommendations so as to be in tune with the sharply different systems that would emerge.

An Alternative, Incremental Approach

The Fuchs-Emanuel and Friedman plans have many desirable features, as does the president’s latest proposal, but they are clearly radical departures from the current system. We admire the combination of universal coverage, government-financed but privately and competitively provided health insurance, linkage of benefits to costs, and advocacy of improved information available to consumers. However, we are not convinced that it is possible to implement such a plan in one step. As an alternative, we propose, therefore, an incremental approach that would move major elements of the health care system in the same directions as those advocated by Milton Friedman and Fuchs and Emanuel.

The Shultz-Shoven set of health initiatives has several components. Unlike Fuchs and Emanuel, we do not propose replacing Medicare and Medicaid completely, nor would we suggest replacing the U.S. system of employment-based health insurance. Instead, we seek to modernize and significantly reform Medicare and Medicaid, improve employer-sponsored health plans, and ensure that those who do not have access to such plans will still be able to obtain affordable major health insurance. We advocate that all Americans have access to strengthened Health Savings Accounts and a more competitive health insurance environment.

The First Step

Health Savings Accounts, enabling individuals to save for their own potential health costs with before-tax dollars and combined with a catastrophic health insurance policy, are now available and are attracting increasing numbers of Americans. Health plans that include HSAs account for a small but rapidly growing segment of the insured population. Approximately five million individuals, many of whom were previously uninsured, are enrolled in HSAs through their employers or individually.6 Now is the time to enhance the quality of Health Savings Accounts in ways that make them more accessible and useful. Here are four suggestions that have been endorsed by many scholars, health care practitioners, and politicians, including President George W. Bush:

- Provide the same tax advantages for any individual who purchases an HSA as are now provided when an employer purchases an HSA for an individual. There should be no discrimination against individual initiative and the self-employed.

- Allow the use of risk adjustment so that individuals with identifiable health problems can contribute, or their employers can contribute for them, larger amounts into their HSAs.

- Make any out-of-pocket health care expenses tax deductible for those with fully funded HSAs.

- Require that all HSAs, including related high-deductible catastrophic insurance policies, be portable, whether or not they were purchased for employees by their employers. A related move would make it possible for individuals to purchase portable HSAs from health insurers. As each HSA is linked to a catastrophic health insurance plan, a national market would be created for such insurance.

These changes in HSAs would make them more useful and more affordable for low-income individuals. They would also make HSAs more likely to be used by employers, units of government, or self-employed individuals looking for a way to provide health care benefits with reasonably predictable costs.

The second reform that would benefit all Americans is the establishment of a more competitive environment for health insurance, thereby making it less costly and more suitable for varying individual needs. The insurance industry is of central importance to the cost, quality, and accessibility of health care. Insurance costs have grown dramatically and continue to rise, but this is not simply a reflection of health costs. Insurance is currently available on a state-by-state basis. Because insurers and the providers they work with have large political clout in most states, insurance laws require broad, expensive coverage that often goes far beyond what most individuals need or want. Devon Herrick, an economist at the National Center for Policy Analysis, reports:

The Commonwealth Fund and e-HealthInsurance.com compared the prices of policies in seven states with varying degrees of regulation. The policies had similar coverage and a deductible of about $500. A 25-year-old male in good health could purchase a policy for $960 a year in Kentucky. That policy would cost about $5,880 in New Jersey. A similar policy available in Kansas for about $1,548 costs $5,172 in New York State. A policy priced at $1,692 in Iowa and $2,664 in Washington State would cost $4,032 in Massachusetts. The difference in premiums is mainly due to state regulations rather than variation in health care costs.7

Parallel bills to allow insurance to be written on a national basis have been introduced in the House of Representatives and in the Senate. If these bills pass, competition will most likely lead insurance companies to offer insurance with varying coverage so that a consumer can buy only the needed coverage, thus making it less expensive. When combined with the right of insurers to sell portable HSAs, including the required catastrophic coverage, these changes would lead to marked improvements in the health care system.

In addition to these improvements, Medicare and Medicaid must be reformed. The escalating costs and solvency of these programs are tough problems to fix. The costs depend not only on the numbers of eligible participants but, more important, on their future health status, the medical technologies available, and the incentives given to participants to consume health care efficiently and effectively. Improvements must be made to these programs and their financial outlook, concentrating first on Medicare while recognizing that some of the ideas that will improve Medicare will also be applicable to Medicaid. We shall first suggest the outline of a modernized Medicare system that maintains and improves the safety net feature of the existing program while enhancing its progressivity and efficiency.

Improve Medicare

The long-term necessity of reforming Medicare stems from its runaway costs and evidence that waste and inefficiency account for a significant portion of its expenses. Medicare costs have increased dramatically in the past forty years, not only in absolute terms but also relative to other prices, wages, and the aggregate size of the economy itself. There is no sign of a slowdown in the growth of Medicare costs. Eventually, however, unless these costs are curtailed, Medicare—and Medicaid, its companion program—will completely swamp the federal budget and the economy as a whole. It is not just the government’s budget that will be unable to sustain the current structure of Medicare; the budgets of the elderly will not be able to handle it either. Medicare reform is essential for long-term solvency.

What are the keys to a comprehensive solution for this looming problem? Much can be done to make the system more efficient. Benefits can be restructured to reduce waste and improve efficiency. A modernized system could produce better health outcomes for less money than does the current design. The innovation and efficiency that accompany competitive markets are needed, as are better-informed consumers who have meaningful choices. Competition is needed so that health care providers who fail to offer high-quality products at reasonable prices are replaced in the market by providers that can. The safety net for low-income individuals must be preserved and even strengthened. A high-quality Medicare program must be designed that significantly reduces the strain on the federal budget. Medicare can be better and cheaper at the same time that it is progressive and compassionate.

How can all these things be accomplished? We come to the same conclusion as that reached by Milton Friedman, Victor Fuchs, and Ezekiel Emanuel: The best solution is a carefully designed Medicare voucher program that takes advantage of a more competitive market for insurance. As included in our ideas for Social Security reform and the transition proposed by Fuchs and Emanuel, those already receiving Medicare benefits would not be moved to the new system, although they could accept the changes if they so desired.

A voucher system would grant each eligible Medicare participant an amount of money with which to purchase comprehensive health insurance. There would be a menu of insurance options including HMOs, such as Kaiser and HealthNet, and HSAs combined with catastrophic insurance. All these plans would compete for participants. The full benefits of competition would thus be brought to the health care field.

The dollar value of the vouchers would differ depending on a participant’s age, gender, and health status, determined from previous medical records. As discussed earlier, the purpose of adjusting the value of the vouchers to health status, commonly called risk adjusting, is to avoid the problem of insurance companies attempting to enroll only the healthiest Medicare participants. Ideally, after risk adjustments, all Medicare participants, regardless of their health status, would be equally attractive customers for health insurance companies. And insurance companies could be justifiably required to take all comers. Already, Medicare Advantage plans are using the risk adjustment concept and insurers are responding aggressively, as pointed out in the previous chapter.

We recognize that risk adjustment calls for careful administration so as to avoid the problem of people cultivating risk. The more the system sticks to objective factors, the less likely is widespread gaming of the system.

The value of Medicare vouchers could also reflect the participant’s earnings history. Participants whose average lifetime earnings place them in the lowest thirtieth percentile would receive the full value of their age, gender, and health-adjusted vouchers. This would permit Medicare participants with relatively low lifetime earnings to choose among alternative health insurers offering comprehensive plans with low deductibles and copayments. Under this plan, the out-of-pocket health care expenses for those in the lowest thirtieth percentile of lifetime earnings would be less than or equal to what they are under the current Medicare system.

On the other hand, those in the top twentieth percentile of lifetime earnings would receive vouchers, adjusted by age, gender, and health status, in amounts just sufficient to purchase catastrophic care insurance policies. All would be allowed to supplement the value of their Medicare grants with their own resources, as in the purchase of tax-advantaged HSAs. A schedule of voucher adjustments based on lifetime earnings would create a sliding scale from those with low lifetime earnings, who would have no reductions, to those with high lifetime earnings, who would face significant reductions.

The lifetime earnings reductions are a type of means testing for Medicare that serves two purposes. The first is to help contain the total costs of Medicare by asking those who are financially able to do so to bear a larger portion of the costs for their own health care while making sure that low-income individuals have an adequate level of Medicare benefits.

The second purpose of lifetime earnings adjustments is to preserve the incentives to save and invest in the economy. The reductions do not depend on either the wealth or income of Medicare participants. Consider, for example, two individuals with the same history of earnings, one a systematic saver and the other a big spender. In retirement, the saver is relatively wealthy with a high income whereas the spender gets by on Social Security and a much lower income. Both individuals would face the same lifetime earnings adjustment to their Medicare vouchers. The advantage of this system of means testing is that it does not discourage saving (or working, for that matter). We label this form of lifetime earnings adjustments “smart means testing.”

We like the Fuchs-Emanuel proposal for establishing a dedicated revenue source for Medicare, although we recognize how adept the political process is at finding ways around restrictions. Of course, Part A has a dedicated revenue source with its 2.9 percent payroll tax. Our Medicare voucher system would merge all of Medicare’s parts (A, B, C, and D) and fund them with the current payroll tax and within a commitment to a balanced federal budget at full employment. This is a way to establish the accountability advantages of tax dedication without introducing a whole new value-added tax system, as proposed by Fuchs and Emanuel.

The age of eligibility for Medicare need not be changed, although a reassessment might be appropriate at some point if life expectancies continue to march upward. Once eligible for Medicare, an individual would receive a health insurance voucher whether or not he or she was still working. This is a significant change relative to the current Medicare practice of acting as the secondary payer for a worker who receives employee health benefits from an employer with twenty or more employees. The proposed change would encourage firms to hire such individuals. Instead of being burdened with the entire health insurance cost for elderly workers, firms would find that the bulk of these costs would be provided for by Medicare vouchers.

Out-of-pocket deductibles, copayments, and the money to supplement Medicare vouchers all could come from HSAs. The extension of such accounts would promote saving among the elderly as well as among working Americans. Pretax dollars could be accumulated in tax-sheltered investment accounts and withdrawn, tax free, for out-of-pocket medical expenses and health insurance costs. Not only could the money be saved for future use, but also unspent funds could be bequeathed to one’s heirs. Because they would be using their own money, people would be encouraged to be prudent when making their health care spending decisions.

The lifetime earnings–adjusted vouchers would work well for the vast majority of Medicare participants. Nonetheless, some people would fall through the safety net. For instance, an individual who had high lifetime earnings might fall into a lower-income category because of unfortunate circumstances or unavoidable costs, such as the need to provide long-term care for aging parents. In such a case, the proposed lifetime earnings–adjusted vouchers would provide only catastrophic health insurance on the mistaken assumption that such an individual would be able to supplement the voucher with personal resources. This is exactly the type of circumstance in which Medicaid comes to the rescue, because it provides a second safety net for those with very low incomes and wealth. Medicaid coverage differs by states, but its minimum benefits would be similar to the comprehensive coverage of Medicare for those with low lifetime earnings. This would retain and strengthen the safety net provided by Medicaid.

The Medicare vouchers program would permit the government to bring future costs of the system under control in several ways. First, efficiency would be enhanced because insurance providers would have to compete with one another for business. Even those participants in the bottom thirtieth percentile of lifetime earners would be involved in the program, structured to give them an element of choice. Second, those above the lowest-income group would be spending more of their own money and therefore monitoring the value-for-money balance more carefully. Third, the vouchers would convert the government’s obligation from one of medical services to one of calculable cash payments.

Almost everyone who has analyzed the future of Medicare has concluded that the current practice of providing its participants with all desired health treatments regardless of cost cannot be maintained for long. Inevitably, some form of rationing or cost-effectiveness calculation will be introduced. The private market almost always makes better rationing decisions than do government bureaucrats. The best way to ration is through the marketplace, from the joint decisions of insurance companies in the design of their alternative policies to the choices made by households among the plans offered. Health care would be rationed in a manner similar to food: People would exercise choice, and those in the lowest-income group would receive assistance, just as food stamps are allocated to the needy.

Improve Medicaid

The advantages of competition in the presence of informed consumers extends to Medicaid as well as to Medicare. The traditional Medicaid system, in which eligibility carries entitlement to a range of services, has come under intense pressure as extensive fraud and misuse have damaged the system and costs have escalated rapidly. All state governments have become concerned about the impact on their budgets of the virtually runaway costs of Medicaid. The result has been an accelerating number of changes by states that obtain waivers under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act. The general trend of state governments shows a movement in the direction of small copayments and deductibles and the use of insurance or health plan vehicles that limit state costs and require Medicaid recipients to contribute more for the services they receive.

The structure of the current system of Medicaid actually discourages people from working. Eligibility depends on income and wealth and varies widely by state and by the medical condition of the recipient. The average annual benefit for a family of four is approximately $12,000, a large number reflecting the fact that a small percentage of families have extremely large health costs. What that means is that an extra burst of work for which someone is paid, say, $1,000, might push that individual above the eligibility line, causing him or her to lose a much larger amount of money. The impact on the desire to work is obvious: There is no incentive to work more if the result is less income. This suggests that one of the many necessary and desirable changes that should be made is the removal of this notch, which is a powerful disincentive to work.

Efforts to reform welfare confronted the same problem, but in that case the eligibility was for money. The solution was to disregard an initial amount of additional earnings and then phase out benefits as earnings increased further. That removed the notch and ensured that as an individual earned money, he or she would always stay ahead of the game.

A further evolution of what is already taking place in the Medicaid waiver system could make it possible to deal with this problem while also enhancing consumer involvement in the costs. Health Savings Accounts contain money, after all, but that money is devoted specifically to health. Suppose the Medicaid system gave those below the poverty line a fully funded HSA. Recipients would then have catastrophic insurance with a deductible and an amount of money that could be spent, no doubt in some prescribed way, on health costs. Unspent money would stay in the individual’s account.

As a Medicaid recipient went to work and earned pay that would put him or her above the poverty line, the funding of the HSA would be gradually reduced. If the household income level reached twice the poverty line, the only remaining Medicaid benefit would be catastrophic insurance, with the family being responsible for funding the HSA. Further income increases would reduce the subsidy to the catastrophic insurance. The big change is that it always would be in the interest of the family to work harder and earn more money.

The HSA plus major medical insurance might be one of the options offered to recipients of Medicaid. As with Medicare, we advocate that participants be encouraged to choose from a menu of quality insurance options. Medicaid participants would have the same risk-adjusted voucher system as Medicare enrollees. Those at the lowest income levels could obtain a good, comprehensive health plan with little or no out-of-pocket money. They would have choice. As their incomes increased, the subsidy of their Medicaid policies would be gradually reduced.

The voucher-style Medicaid program that we are proposing would cover more people than does the current Medicaid program. Today those just above the income limits are unable to obtain Medicaid health insurance. With our proposal, those above the existing limits would still receive some Medicaid assistance.

As with Medicare, funding for Medicaid could be derived from a commitment to a balance in the federal budget at full employment. But enhancements to these programs should not be paid for out of general revenues of the federal government beyond the slice identified. It has proved too easy to ignore the fact that general revenues will be increasingly scarce in the future. Better decisions will be made about the scale of both Medicaid and Medicare if they are funded from identifiable tax sources.

We think the first step toward comprehensive health insurance reform is to empower Medicare and Medicaid participants with choice and to improve the information available to them for informed decision making.

We stop short of the full Fuchs-Emanuel and Friedman approaches to health insurance for those who are not elderly or in the lowest income brackets. We support the Fuchs-Emanuel idea of an independent Institute for Technology and Outcomes Assessment. Such an institute can develop information on prices and outcomes and identify and publicize best practices and new developments. We think that it is too soon to abandon completely the employment-based health insurance system that is the backbone of today’s health delivery system. Employers are moving toward offering consumers a choice of plans, employees are rapidly adopting Health Savings Accounts, and the increased use of copayments and deductibles means that consumers are spending more of their own money.

We think that it is wise to follow along with these trends as they move toward other necessary changes. We have already listed ways that HSAs can be strengthened. They should be made more widely available, restrictions on their availability should be eased, and they should be extended to those who do not have employer-based health coverage. Health insurance markets and regulations should be national, not statewide. Catastrophic health insurance should be universally available so that all Americans can protect themselves from the unexpected expenses of big-ticket health events.

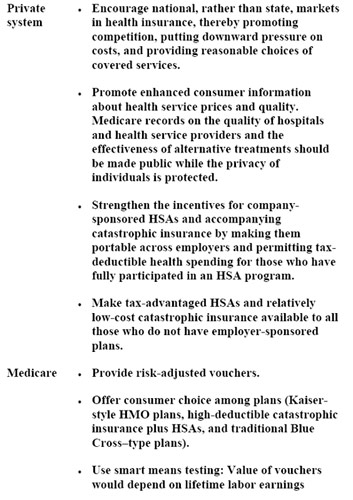

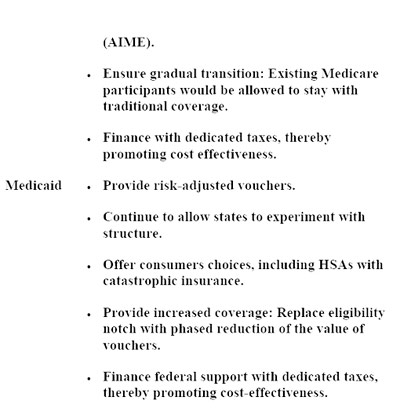

Our overall plan, as summarized in table 10.1, is to modernize radically Medicare and Medicaid, introducing more choice, better information, and smart means testing. We think that costs can be brought under control by providing a specified amount of money for health care rather than an open-ended set of services and by empowering consumers to choose among health care options, just as they make selections in other realms, such as food and housing. Markets that function well make efficient rationing decisions, so they do not experience the kind of affordability crises that health care now faces. We propose to extend this efficiency to our health care programs.

The Opportunities Ahead

The health care system established in the last half of the twentieth century provided access to medical services for many Americans who otherwise would have had great difficulty obtaining adequate care. As discussed in chapter 7, the structure of that system produced a stool with only two legs, one of providers and one of financiers. That system led to large unwarranted and unnecessary costs, fraud, and inefficiency on a broad scale. As these costs mounted, they made the system less and less affordable. Employers under competitive pressures and governments under budgetary pressures have reacted in a wide variety of ways. They have taken steps that, in effect, are building a consumer leg for the stool. Suggestions made here would strengthen that leg and afford the possibility of an improved health system. Competition would rid the system of much of the waste and misallocation of resources described in chapter 7. Universal access would be available to all Americans and would be built, in a sense, from the bottom up, the American way, as distinct from a system of universal coverage built from the top down and administered by a bureaucracy in the European way.

The ingredients are already in place. The Medicaid system, as rearranged in the way recommended here, would provide the resources needed for everyone below a poverty-like band drawn by the states. The Medicare system already provides for almost all who are sixty-five and older. If the coverage were in the form of funds, as we recommend, then resources would be in the hands of consumers. If reasonable costs could be calculated, there is every reason to believe that employment-based insurance, particularly in the form of high-deductible health plans and HSAs, would become virtually universal. In addition, revised HSAs could be offered at a reasonable cost to the self-employed. Others who may fall between the cracks of these different systems would be much more inclined to provide for themselves if HSAs were readily accessible and if insurance suited to their needs were available at a reasonable price. The ample funds already allocated within the present multifaceted health finance system would go to individuals who are becoming increasingly sophisticated consumers as they are provided with the information they need.

Health care affects each of us in a very personal way. We expect basic medical services to be broadly available. This objective can be achieved by changing the structure of the present health care system. With an improved structure in place, costs can be contained, and the health needs of all Americans can be adequately served.

Table 10.1 Summary of the Shultz-Shoven Health Initiatives