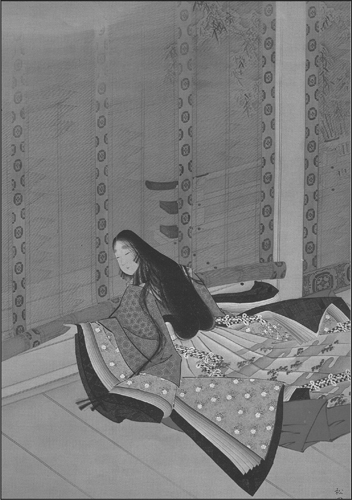

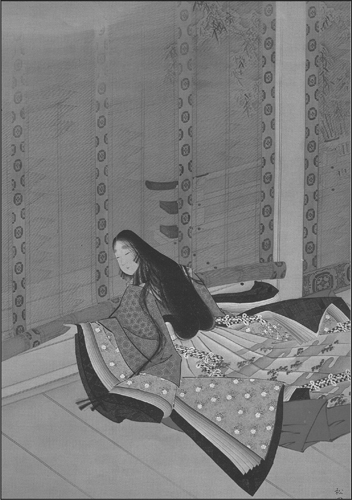

Sei Shonagon

965—1010

I really can’t understand people who get angry when they hear gossip about others. How can you not discuss other people? Apart from your own concerns, what can be more beguiling to talk about and criticize than other people?

How can you not discuss other people? We all do it.

There is simply nothing more fascinating to people than other people. This has been true for at least a thousand years. The words above were written in the tenth century, by a lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan.

We know her by the name of Sei Shonagon, but that would not have been what she was called. Sei was her family name, and the word shonagon meant “junior counsellor,” probably the job of one of her male relatives. Some scholars think her personal name was Nagiko, but here she’ll be referred to as Sei.

Sei’s masterwork, called in English The Pillow Book, is not a memoir, nor a diary, nor poetry, but in a way it is all of these. Written in snippets during ten years at the royal court, The Pillow Book is a collection of lists, anecdotes, poems, gossip, reminiscences, and astute observations of the people and rituals that Sei encountered each day.

Sei was born in the year 965 CE. She arrived at court in her mid-twenties to serve Sadako, the first wife of the Emperor Ichijo. The routine life of the women in the palace had much to do with appearing lovely, preparing the tea ceremony, and providing witty conversation and entertainment for each other, as well as for the men.

The identity of Sei’s mother is unknown, but her father and grandfather were both famous poets in Japan during this time called the Heian period. Heian means something close to “peace and tranquility.” Art, poetry, and literature were particularly prized by the Japanese nobility. Educated Japanese men prided themselves on writing in Chinese, a language forbidden to the women. Instead, the women wrote with a collection of symbols called hiragana, using a brush and ink. No one had ever written a book like Sei’s—in any language—so there is no way of guessing what inspired her to make her mark in so unusual a way.

All we really know about Sei is what she revealed in her own book. She was fiercely opinionated, sharp-eyed, and ruthless in her descriptions of other courtiers. She was quick-witted and flirtatious, with two main passions: she adored her Empress with unfaltering admiration, and she prized poetry above almost anything else.

However critical Sei may have been of her fellow courtiers, her book often describes Empress Sadako’s beauty and exquisite kimonos: “Where else would one ever see a red Chinese robe like this? Beneath it she wore a willow-green robe of Chinese damask, five layers of unlined robes of grape-colored silk, a robe of Chinese gauze with blue prints over a plain white background, and a ceremonial skirt of elephant-eye silk. I felt that nothing in the world could compare with the beauty of these colors.”

Sei was miffed when Sadako showed a momentary preference for anyone other than Sei, but delighted and gratified when she was clearly the favorite. The women often teased or complimented each other through impromptu poems, like this one:

The years have passed

And age has come my way.

Yet I need only look at this fair flower

For all my cares to melt away.

Just as text messages are a common form of communication between friends and sweethearts today, the exchange of poetry was how word got around in Sei’s life at court. A servant could be ordered (at any time of the day or night) to provide paper and ink for composition, and then to carry a poem to someone else in the palace. The choice of paper was a kind of declaration; its weight and color were clues to the feelings of the sender. Sei often mentioned—sometimes critically—what the poem looked like, as well as the words it contained. In her list of “Unsuitable Things,” for instance, she mentions “Ugly handwriting on red paper.”

The setting that Sei reveals is as foreign to the modern Western reader as the world of a fantasy novel. But inside the ancient and exotic Emperor’s palace, thanks to Sei’s illumination, the people—the women in particular—are shown to share feelings and flaws that are utterly familiar, like those remarks about gossiping.

Altogether, The Pillow Book consists of about 320 pieces, half of which are lists. Here is a sampling of the lists and some of what she included under each evocative title:

Things that can’t be compared

Night and day.

Laughter and anger.

Old age and youth.

The man you love and the same man once you’ve lost all feeling for him seem like two completely different people.

Things that Pass by Rapidly

A boat with its sail up.

People’s age.

Spring. Summer. Autumn. Winter.

Scruffy Things

The back of a piece of embroidery.

The inside of a cat’s ear.

Occasions for Anxious Waiting

You become very anxious when you have to make a quick response to someone’s poem, and you can’t come up with anything.

Elegant Things

A white coat worn over a violet waistcoat.

Duck eggs.

Plum blossoms covered with snow.

A pretty child eating strawberries.

Things That Make Me Happy

I know I shouldn’t think this way, and I know I’ll be punished for it, but I just love it when bad things happen to people I can’t stand.

Hateful Things

Very hateful is a mouse that scurries all over the place.

One is just about to be told some interesting piece of news when a baby starts crying.

A person who recites a spell himself after sneezing. In fact I detest anyone who sneezes, except the master of the house.

Another hateful thing, according to Sei, was when someone’s poetry was not admirable: “I particularly despise people who express themselves poorly in writing.… It’s bad enough to receive poorly written letters oneself, and just as disgraceful when they’re sent to others …” But she also exults, “If letters did not exist, what dark depressions would come over one! … a letter really seems like an elixir of life.”

Sei recorded her own witticisms in an almost gloating tone. She was quick to pass harsh judgment on everyone’s behavior and appearance and often had spats or rivalries with both men and women whom she deemed in some way unworthy.

A reference to Sei appears in the diary of another woman who achieved fame as a writer during this era. Lady Murasaki Shikibu wrote a romantic novel called The Tale of Genji. She described Sei this way: “Sei Shonagon has the most extraordinary air of self-satisfaction.… She is a gifted woman, to be sure. Yet, if one gives free rein to one’s emotions even under the most inappropriate circumstances, if one has to sample each interesting thing that comes along, people are bound to regard one as frivolous. And how can things turn out well for such a woman?”

Sei’s beloved Empress Sadako died two days after giving birth, in the year 1000. Sei withdrew from court and there is no further trustworthy information about what happened to her. One story says that she died alone and very poor, but that may have been a rumor circulated by her rivals.

What we do know is that her collection of words, her “scribbles,” have lasted centuries more than most writers ever dream of, making the following lines true indeed.

… if I happen to come by some lovely white paper for every day use and a good writing brush … I’m immensely cheered, and find myself thinking I might perhaps be able to go on living for a while longer after all.

Sei Shonagon’s notes were delivered within minutes of writing them—almost like e-mail. And if she did not receive a reply at once, she twitched with irritation.

Margaret Catchpole’s letters took months to arrive at their destination, and she could never be certain whether she’d hear any answer at all …