Margaret Catchpole

1762—1819

i am sorrey I have to inform you this Bad newes that I am a going a way on wedensday next or Thursday at the Longest so I hav taken the Libberty my good Lady of trobling you with a few Lines as it will Be the Larst time I ever Shall trobell you in this Sorrofoll Confinement my sorrowes are very grat to think I must Be Bannished out of my owen Countreay and from all my Dearest friends for ever …

Margaret Catchpole wrote this letter from prison, where she had been waiting to learn the punishment for her crime of stealing a horse. She had just heard the worst possible news. She was not to be hanged, as she had hoped, but instead would be transported away from her homeland of England for the remainder of her life, to a distant place now known as Australia.

Crime affected nearly everyone who lived in England during the eighteenth century, especially in the towns and cities. The capital city of London was bursting with new arrivals from the countryside, all struggling to stay alive by whatever means they could among the gin stalls, dark alleys, and rat-infested lodgings. Survival sometimes meant stealing and cheating, or worse.

Margaret came from a tiny seaside village, but, like thousands of others seeking a fortune, she traveled to London when she had something to sell—in this case, the very horse she had stolen and ridden to get there!

Margaret had grown up poor and unschooled on the farms where her father worked as a ploughman. During those years, she’d learned to ride a horse with great confidence. She was a servant in several homes before being hired by the Cobbold family. It was Mrs. Cobbold who taught her to read and write a little, between helping with the children and the kitchen chores.

There is now great suspicion about the legend of Margaret’s daring deeds, but even the facts that can be checked tell quite a story. Her first biographer was the Reverend Richard Cobbold, little Dick, son of Margaret’s employer. His book was called History of Margaret Catchpole, a Suffolk Girl. It is the Reverend Cobbold’s fault that Margaret’s true history is so unclear. He recognized that his family had been close to a notorious celebrity and he could not resist adding a number of fictional episodes, characters, and motives to his account of her life.

He gave her credit for having rescued various Cobbold children from terrible accidents—according to him, she shielded two from a falling wall, and saved another from drowning. But the first certain drama in Margaret’s life took place when she was fourteen. She galloped bareback for nine miles to fetch a doctor for her ailing mistress, causing astonishment throughout the county. It was not the same horse that later got her into trouble, but it was the same skill as a rider.

After many years of loyal service, in 1795 Margaret stopped working for the Cobbolds. She was thirty-three years old. Nearly two years later, she stole their horse, “which she rode from thence to London in about 10 hours dressed in a man’s apparel, [and] having offered it for sale she was detected.”

The Reverend Cobbold’s book claimed that Margaret was under the influence of a scoundrel sweetheart named Will Laud, but that romance cannot be proved as fact. Having lived in a town beside the ocean, where smuggling was a common trade, it is possible that Margaret was acquainted with seedy characters, but not necessarily in love with one of them. However, she’d always been a “good” girl, hard-working and loyal. When such a person performs a desperate and foolish deed, the obvious question is, “Was this for love?” We’ll never know.

At the time of Margaret’s crime, there was not yet an official police force, so the court system was clogged with troublemakers of all kinds. Back then there were severe penalties for offenses we would consider minor today. Two hundred crimes were punishable by hanging! Apart from the serious crimes, like murder, arson, and highway robbery, some of the milder offenses were: pilfering anything worth more than five shillings, such as a hat, a lady’s slip, or a piece of meat; picking someone’s pocket of a silk handkerchief or wallet; and—as Margaret had discovered—stealing any sort of animal. All this meant that the jails were dangerously crowded, dingy, and awful-smelling, as well as teeming with contagious diseases. Officials were forced to consider alternative methods of punishment.

The explorer James Cook recommended to the British government that the remote Botany Bay he’d discovered in 1770 would make an ideal destination for surplus prisoners. The actual settlement was along the coast from Cook’s original site, but to this day, the phrase “Botany Bay” is synonymous with banishment to a bleak land full of rough characters.

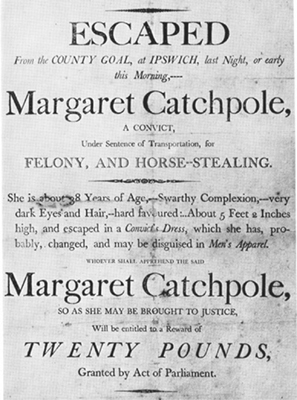

Margaret was held for three long years in a local jail while awaiting the ship that would carry her away from England. The idea of traveling to an unknown land must have frightened the sense right out of her head, because in March of 1800, Margaret staged a daring escape from the Ipswich prison. She climbed up and over a twenty-two-foot-high spiked fence to freedom. But a week later she was recaptured, “dressed in a sailor’s habit, and safely conducted back to her old compartment.”

Imprisoned until August, “she again received the death sentence but [was] reprieved before the Judge left the town.” She may have felt more cursed than lucky to have had her penalty reduced to Transportation for Life.

The courts had been exiling people to Australia since a convoy of eleven ships, known as the First Fleet, had sailed from England in 1787, carrying nearly 800 convicts. Altogether, during eighty years of Transportation, more than 162,000 criminals became the pioneers of this huge unknown continent. The human cargo was accompanied by cows, sheep, goats, hogs, chickens, and five rabbits. This menagerie was intended to supply ongoing generations, just as the people were.

Finally, in May of 1801, with ninety-five other female prisoners, Margaret departed from home on a ship called the Nile. One hundred and seventy-six days later (a trip that today takes about seventeen hours by airplane), she disembarked, just before Christmas, in Sydney Cove on the other side of the world. The colony must have seemed as fearfully different from England as the moon might be—but even farther away: “At least one could see the moon from England.”

The conditions on board the Nile had certainly been grim, making the sight of land—even such a strange land—a joyous relief. The settlers already in residence would have been just as excited to greet the new arrivals. A ship meant letters from home, even if the news was nine months old. There was a war going on in Europe, where a cocky French general named Napoleon Bonaparte was taking steps to declare himself emperor. A ship would also bring much-needed supplies as well as fresh workers, servants, and women to a population hardly yet able to support itself with crops and fishing.

Many of the female criminals originally destined to be hanged on the gallows had had their sentences commuted to Transportation because the officials realized there was a desperate need for young women to bear children, to supply future generations for the new colony. Some of these women eagerly paired up with soldiers, handsome in their scarlet uniform jackets, and traded their charms for better treatment or reduced labor time. Margaret Catchpole was past the age when she could provide children, but she found other ways to contribute to the settlement.

The First Fleet convicts had lived in tents or crude cabins, but by the time of Margaret’s arrival, thirteen years later, there was a real town with simple cottages for the convicts to live in, most with verandas to shade them from the scorching sun. Bush flies buzzed about constantly and goats and dogs roamed the laneways. Enterprising residents recalled the streets of London by selling oysters or pies from market stalls. After a few years, the convicts were obliged to wear black-and-yellow uniforms to distinguish them from the free settlers, but there was no such need when Margaret was newly landed; almost every European living in Sydney Cove was either a prisoner or a guard.

Although there were no high fences to climb, the inmates of this prison town had no interest in escaping. Fear kept them in place. Margaret’s letters often refer to the “savages” who roamed the vast open wilderness beyond the edge of town. When the British had arrogantly claimed this territory for their king, they’d ignored the entire aboriginal population, who had lived there for at least twenty thousand years. Members of the Gweagal clan were the people most immediately affected by the invasion of the pale men in “big canoes,” and they were not happy about it.

There were many clashes over the years, with killings on both sides. Certainly the convicts were wary of these “savages” who could throw spears with fatal accuracy. But the white men had even deadlier weapons: first guns, and then smallpox. This disease, carried unintentionally from England, killed countless aborigines.

Margaret’s first job in Sydney Cove was as a cook for the commissary, Mr. John Palmer, whose wife later became a good friend to Margaret. Cooking must have been one of the preferred positions, far easier than farm work or building. Had she already shown that her intention to stay out of trouble was more than an idle promise?

Throughout her sentence, Margaret wrote letters to friends and acquaintances back home, though paper was scarce and her spelling was terrible. Why did she choose to write to Mrs. Cobbold, the very woman whose horse she had stolen? Why was she compelled to be in touch with other people who must have seemed like foggy memories as the years sailed by? Being nearly illiterate, why did she write at all?

We are lucky that she did, because the eleven letters that still exist are now considered rare documents and are kept in a museum. It turned out that Margaret was a unique and important witness to the original European colony in Australia. We know certain details thanks only to her scrawls.

On January 21, 1802, after one month of living in the far-away, unfamiliar country, Margaret began her letter to Mrs. Cobbold using these words: “honred madam with grat plesher i take up my penn to a Quaint you, my good Ladday, of my saf a rivel at port Jackson new South Wales sedeny on the 20th Day of Desember 1801 …”

Margaret’s unschooled spelling sometimes makes her letters difficult to read. Here is a translation:

With great pleasure I take up my pen to acquaint you, my good lady, of my safe arrival at Port Jackson, New South Wales, Sydney, on the 20th day of December, 1801 …

It is possible, reading her words aloud, to hear how her accent might have sounded, as she likely spelled out the letters the way she heard herself speak.

The first letter goes on to say: “… It is a Grat deel moor Lik englent then ever i Did expet to a seen for hear is Gardden stuff of all koind—expt gosbres an Currenes and appelles.” More clearly spelled, this would be: “It is a great deal more like England than ever I did expect to have seen, for here is garden stuff of all kind, except gooseberries and currants and apples …”

(For clarity, further transcriptions of Margaret’s letters will have the correct spelling, unless noted.)

It is touching, after all she’d been through, to imagine Margaret being homesick for something as simple as gooseberries. But the new world was not entirely gardens and beautiful parrots and pretty woods. Without giving a reason, she states, in capital letters: “FOR I MUST SAY THIS IS THE WICKEDEST PLACE I EVER WAS IN ALL MY LIFE.”

She is pleased to report that not one woman had died on the voyage, and that as her work assignment is minimal, she has a fair amount of freedom, only being expected at a “general muster. Then I must appear to let them know I am here.”

Even in a community of convicts, however, Margaret explained that those who broke the rules ended up in a worse situation: “They have their poor head shaved and sent up to the coal river and there carry coals from day light in the morning till dark at night, and half starved, but I hear that is a-going to be put by, and so it had need, for it is very cruel indeed.”

In other cases, offenders were banished to an isolated isle off the coast: “Norfolk Island is a bad place enough to send any poor creature, with steel collar on their poor necks, but I will take good care of myself from that.”

She signed off, “from your unfortunate servant, Margaret Catchpole.”

But then, “Madam,” she instructed Mrs. Cobbold in a postscript. “Be so kind as to let Doctor Stebbings have that side of the letter …”

There was a shortage of paper, but Margaret was resourceful. She used the same piece of paper to write letters to two people, trusting that when one had finished reading, he or she would deliver the note to the other recipient. There was no need to remember any street address, as only the person’s name and village were needed to guarantee delivery.

Dr. Stebbings, according to Reverend Cobbold’s book, was the doctor to whom Margaret had galloped so many years before, seeking medical aid for her mistress. Whether she had known him quite so long as that, he seems to have been familiar with several inmates at the Ipswich jail, so perhaps he attended them as prison doctor. Margaret reported on other local women who had made the crossing with her: “Barker is alive but she was very much frightened at the ‘rufness’ of the sea. She used to very often cry out, ‘I wish I was with my dear Mr. Stebbens for I never shall see Ipswich no more,’ but she is much the same as ever …”

Here is Margaret’s description (showing the prejudice typical in those days) of the new race of humans she was encountering:

To Dr. Stebbings:

… Pray give my best respects to all my old fellow prisoners and tell them never to say ‘dead hearted’ at the thought of coming to Botany Bay for it is likely you may never see it, for it is not inhabited, only by the blacks, the natives of this place—they are very savage for they always carry with them spears and tomahawks so when they can meet with a white man they will rob them and spear them. I for my part do not like them. I do not know how to look at them—they are such poor naked creatures. They behave themselves well enough when they come in to my house for if not we would get them punished. They very often have a grand fight with themselves, 20 and 30 all together—and we pray to be spared. Some of them are killed. There is nothing said to them for killing one another.

Relations between the white colonists and the aboriginal people continued to be uneasy and even hostile. Margaret added a postscript in the note to Dr. Stebbings:

… the Blacks, the natives of this place, killed and wounded 8 men and women and children. One man, they cut off his arms half way up and broke the bones that they left on very much, and cut their legs off up to their knees and the poor man was carried in to the hospital alive. But the Governor have sent men out after them to shoot every one they find, so as I hope I shall give you better account the next letter.

The next letter was a long time coming. Margaret and the other convicts depended on ships for their postal service. In one letter she said, “I hope, my good lady, you write to the first transport ship that do come out for I should be very glad to hear from you,” and again later, “By this day twelve months I shall be in great hopes of a return of a letter.” What she means is that it will be six months before her letter will reach England, and six months for the next ship to come back—a full year before she can hope to hear a reply!

In nearly every note, Margaret provides an update on the cost of things, such as tea, sugar, salt beef, mutton, “fifteen shillings for a pair of shoes,” fabric, soap, and “fish is as cheap as anything we can buy, but we have no money to trade with here.”

The next existing letter is addressed to her Aunt and Uncle Howes, dated December 20, 1804, when there is summer weather in Australia. It was probably written in time to be put on a ship departing for England: “Hoping they are all in good health as it leave me—Bless God for it—and as young as ever and in good spirits I will assure you uncle I should be almost ready to jump over St. John Church, which is the first church that is finished in the country.”

She mentioned early on that this is the fourth letter she had sent so far—probably one each year—and named the boats that carried them. She was “hoping that I should have had a letter long before this. Time here is long—it’s enough to make me go out of my mind to see so many letters come from London and poor I cannot get not one.”

Even so far away, Margaret must have known that her homeland was at war with Napoleon. She told her uncle to think what a “comfort it would be for me to hear from you all, as I hear England is in a very bad state.”

New South Wales did not feel much safer: “This is a very dangerous country to live in, for the natives they are black men and women. They go naked. They used to kill the white people very much but they are better—but bad enough—now. The black snakes is very bad for they will fly at you like a dog and if they bite us we die at sundown. Here is some 12 feet long and as big as your thigh.”

She went on to say: “I am in great hopes that—please God—I should live so long as 2 or 3 years. I shall have that pleasure and that great joy of seeing you all, for this Governor is a very good man to pardon such as has heavy sentences for life. Here have been a great many that have got their free pardon.” She explained that the young man who would be delivering this letter to her aunt and uncle had been a footman in a colonial household where she’d been a dairy maid, both of them convicts. He “was for life but now he is come free to his own home, which is in London.”

Being pardoned and released back into the world, to live how and where they chose, was a dream that sustained Margaret and most other prisoners throughout their terms.

The summers were hot, she wrote, and the winters cold, not with snow but “just very white frosts.… Here is a few apple and pear trees and grapes, a few oak trees but no other sort except petches and apery Cot [peaches and apricot], no gooseberries nor currants.” Still missing gooseberries after so many years!

She finished with a blessing: “So I must conclude with all my best prayers and wishes to you all—and I remain your loving cousin.”

Enclosed in the letter of 1804 was a separate note to Mrs. Cobbold:

I keep myself free from all men and that is more than any woman can say in the whole colony, young or old—for the young Gairles [girls] that are born in this country marry very young at 14 or 15 years old. Everything is very forward in this country—but very uncertain—we may have a good crop of grain on the ground today and all cut off by the next in places, by a hailstorm or a blight or a flood. On Monday last … a hailstorm went over in places and cut down the wheat just as it was in bloom. The hail stones was as big as pigeon’s eggs.…

The natives are not so wicked as they were. They are getting very civil. But will work very little—they say the white man work and the Black man patter—the word patter is eat—they are great creatures to fight amongst themselves with spears …

As in nearly every letter, on October 18, 1807 she listed the prices of common necessities:

Shoes 10 and 13 shillings per pair, no linen cloth of no sort to be got, everything very dear indeed, no paper to be got for newspapers. Thread at this time is 1 shilling per skein, but I have a little left of that you sent me in that very nice box. That was a great comfort to me as I had been so very ill at that time and under doctor Mason’s care, and about 8 months ago, to oblige Mrs. Palmer, I took a very long walk to 30 miles and overheat myself. I come out with blisters on my back as if I had been burnt by small coals of fire and swelled so bad that I thought I should have been dead very soon. But Bless be to God I did recover.

She went on to ask, “If you have any knowledge of Governor Bligh and can petition to him, there is no doubt but something would be done for me as I behave so well and never get into no trouble.” (William Bligh was the fourth governor of New South Wales, but had become notorious when he captained a ship called HMS Bounty. His crew staged a mutiny and rebelled against their captain. Captain Bligh, with a few other officers, was set adrift in a small boat and sailed an amazing 3,618 nautical miles to safety.)

Most of the letter written on October 8, 1809, told of a devastating occurrence the previous spring when the Hawkesbury River flooded its banks and destroyed crops and homes for miles. In today’s world, the television news makes us all familiar with the destruction from tornados, tsunamis, and hurricanes. Margaret’s letter, however, is the only existing eyewitness account of this calamity:

… I am almost broken-hearted—first with the floods, 2nd with fear, 3rd with such surprising high winds that cleared acres of standing timber and trees that were of a very great size. We was afraid to stop indoors, my good lady. Here have been a flood in the month of May which distressed us very much. The next flood—on the last day of July and the first day of August—the highest that was ever known by the white men—went over the tops of the houses and many poor creatures crying out for mercy, crying out for boats, firing off gun in distress. It was shocking to hear. This is the second time that one Thomas Lacey, his wife and family, was carried away in their barn.… They made holes in the thatch and was taken out by men in boats.… Many a one was drowned and at the time the flood was at the height, we all was in great fear we should be starved when the wheat stacks, barns and houses went. Many thousand bushels of Indian corn was washed away. We make bread of that instead of wheat. Most part of the wheat that was in the ground was killed by the flood.… I rent a small farm—only 20 acres—but half of it cleared. I live in my little cottage all alone except a little child or two come and stop with me. My good lady, you know I am very fond of children.… I should have done very well had not this shocking flood come—it have made me very poor. My loss is about fifty pound and within a very little of loosing my own life by the ground caving away.

One of William Bligh’s initial acts as governor was to distribute relief provisions to the farmers hurt by the flood, assistance that would have pleased Margaret.

Richmond Hill September 1st 1811

Honoured Madam, On the 28th of August I received my cedar case that Captain Pritchard should have brought. It is almost 2 years ago since he landed the troops here. Mrs. Palmer my worthy good friend took care of it in her own store room till I could go down myself and when I heard of it I set off and walked all the way down, and it is fifty miles from Richmond Hill to Sidney.

Margaret was appreciative and homesick whenever she received gifts from her former employer: “The cap you sent me off your head was a great comfort to me. I put it on and wear it. I drink the tea with tears and heavy heart.”

She says in this letter that although she is nearly fifty, she is still healthy: “i have Lorst all my frunt teeth. i can Stur a Bout as Brisk as ever and in good spirites.” Clearly, her spelling never improved. “i am Liven all a Loon as Befor in a very onest way of Life—hear is not one woman in the Coloney Liv Lik my self.” Translation: “I am living all alone as before in a very honest way of life. Here is not one woman in the colony live like myself …”

It seems to have been the widely accepted custom that everyone find a mate to live with, married or not, perhaps to share costs as well as company. Margaret never married, did not share her little cottage, and never had children of her own. But, learning as she went, she delivered dozens of baby colonists and was so dedicated a nurse and midwife that the maternity ward of Hawkesbury Hospital, Windsor, bears her name. She eventually earned enough money to open a general store in Hawkesbury.

In January of 1814, Margaret heard the long-awaited news that she had been pardoned by William Bligh’s replacement, Governor Macquarie, fourteen years into her life sentence. She was fifty-four years old. She was now free, and could have returned to England. Why didn’t she go? Would the passage have cost more money than she could put together? Was she afraid of repeating that long, perilous voyage? Had she heard perhaps that Mrs. Cobbold had died?

Or possibly, after so much time, Margaret finally felt that she was at home in New South Wales. Whatever the reason, she stayed there, minding a little shop and delivering babies, until she died of influenza four years later.

In her first letter from the colony Margaret wrote, “I was tossed about very much indeed, but I should not mind it if I was but a-coming to old England once more, for I cannot say that I like this country—no, nor never shall.” When had she changed her mind?

Margaret Catchpole crossed about 22,000 ocean miles against her will. She likely spent most of the voyage below decks in misery.

Mary Hayden Russell set out eagerly to sea and was mesmerized by the majesty of the rolling waves—a good thing, because she’d be sailing far from home for more than a year …