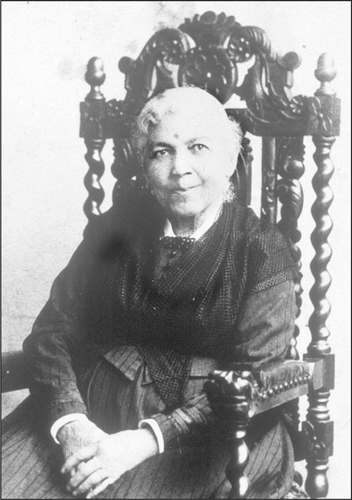

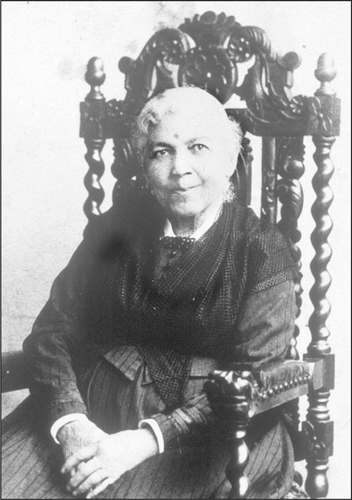

Harriet Ann Jacobs

1813–1897

“I was born a slave,” wrote Harriet Ann Jacobs, in the first sentence of her memoir. “But I never knew it till six years of happy childhood had passed away.”

Those six years gave her a taste of what life should be for every child, and became a memory to look back on during the many wretched decades to come.

If Harriet Jacobs had not learned to read and write, she would have been swallowed up in history, another faceless, nameless slave, relentlessly tormented, without anyone today knowing a single thing about her misery—or her triumph.

Being literate gave Harriet a weapon that she used to trick her pursuer once she’d escaped from bondage, and then to expose the horrors of slavery as few slaves had been able to do before, by writing a book (using the pen name Linda Brent) called Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. It is a remarkable account of her youth in the southern United States, and it is still in print more than a century after Harriet’s anguished run for freedom.

Harriet and her mother, Delilah, were both “owned” by a kindly woman named Margaret Horniblow. Although it was frowned upon to teach slaves to read or write, Margaret did just that, making clever Harriet (nicknamed Hatty) an unusually educated slave child. Margaret taught Hatty how to sew, as well, a skill that would mean survival later in life.

A law against slave literacy was passed in North Carolina when Hatty was a teenager. The official wording began this way: “Whereas the teaching of slaves to read and write has a tendency to excite dissatisfaction in their minds and to produce insurrection and rebellion, to the manifest injury to the citizens of this State …” The law goes on to declare that it is forbidden to provide slaves with books or pamphlets, including the Bible. A white person breaking this law would be fined or imprisoned. An African American would be imprisoned or whipped, “not exceeding thirty-nine lashes nor less than twenty lashes.” The same punishment of thirty-nine lashes would be given to any slave who tried to learn to read.

Harriet Jacobs was certainly “dissatisfied” and often cleverly rebellious, but knowing how to read was not the cause.

Hatty lived with her younger brother, John, and her parents, Elijah and Delilah, along with her grandmother, Molly, who worked as the cook and indispensable housekeeper at Horniblow’s Tavern. Elijah was an expert carpenter, and Delilah was lucky to work indoors instead of being sent into the fields. The tavern was central to the social life in the town of Edenton, as well as the site of the county slave auctions. Young Hatty probably witnessed some of those proceedings, but they were not mentioned in her book.

When Hatty was six, her mother died. As sad as this was, she continued to live in the heart of the family who “fondly shielded” her from the reality of slavery. It took another few years and the death of her owner, Margaret Horniblow, before Hatty’s life changed dramatically.

Hatty prayed that her mistress might have bestowed one final kindness: “I could not help having some hopes that she had left me free.” But, “after a brief period of suspense, the will of my mistress was read, and we learned that she had bequeathed me to her sister’s daughter, a child of five years old. So vanished our hopes.”

Hatty wrote, “I would give much to blot out from my memory that one great wrong.” Considering all that happened to her later, it is remarkable that Hatty’s forgiving spirit let her remember that “while I was with her, she taught me to read and spell: and for this privilege, which so rarely falls to the lot of a slave, I bless her memory.”

What Hatty would never know is that Margaret’s will had not been signed. Hatty had been bequeathed to Margaret’s little niece, Miss Mary Matilda, in a hastily scrawled addition to the will the day that Margaret died. There has since been speculation that Margaret was not the author of that fateful postscript, that perhaps the villain in Hatty’s life story—Mary Matilda’s father—had sneaked in to betray her.

However it happened, Hatty now learned what it meant to be a slave. She moved into the household headed by the father of her new mistress, Dr. James Norcom, called “Dr. Flint” in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Perhaps the instinct to remain hidden prompted Hatty’s decision to disguise her characters. Along with changing her own name, Hatty gave pseudonyms to other family members, as well as to this man who would torment her all of his life.

Hatty’s brother John and her Aunt Betty were both in the Norcom household, too, but the transition was still a difficult one. Not long after she arrived, “she awakened to sounds that would ring in her ears for decades: the hiss of a whip, accompanied by the pitiful pleas of a slave.”

Slowly, she adjusted to her new situation, where her duties were to dress and care for “Little Miss,” and to help with household chores during the child’s naptime. Then came the terrible news of Hatty’s father’s sudden death. Hatty’s owners did not allow time for mourning, as they had considered Elijah to be an untrustworthy character. “They thought he had spoiled his children, by teaching them to feel that they were human beings. This was blasphemous doctrine for a slave to teach; presumptuous in him and dangerous to the masters.”

When Hatty turned fifteen, Dr. Norcom was about fifty years old, and made his intentions clear. “My master began to whisper foul words in my ear. Young as I was, I could not remain ignorant of their import.” For a girl who had been raised by her grandmother to be respectful and pious, the doctor’s attentions were loathsome. “He told me I was his property; that I must be subject to his will in all things.”

Almost worse for Hatty was the effect that her master’s behavior had on his wife, Maria. She had been only sixteen when she became the second Mrs. Norcom. She now had seven children. She was understandably hurt and angry that her husband was doggedly pursuing another woman, but she directed all her fury at Hatty, as if it were somehow her fault.

Meanwhile, Hatty had met someone—a free black man—whom she truly cared for: “I loved him with all the ardor of a young girl’s first love. But when I reflected that I was a slave, and that the laws gave no sanction to the marriage of such, my heart sank within me.”

A slave was not allowed to get married without permission from his or her master, which Dr. Norcom would not give. He hit her, and swore that if he caught her suitor anywhere nearby, “ ‘I will shoot him as soon as I would a dog.’ ” Hatty drummed up her courage to beg Mrs. Norcom to intervene, but that woman’s response was grim: “ ‘I will have you peeled and pickled, young lady, if I ever hear you mention that subject again.’ ”

In the meantime, Mrs. Norcom unintentionally did Hatty a favor, insisting that Hatty no longer sleep under the same roof as her husband. She was sent back to live with Molly, her grandmother, and only work by day for the doctor’s family. Hatty could finally rest at night, though Mrs. Norcom was often mean and vengeful through the working hours.

“The secrets of slavery are concealed like those of the Inquisition,” Hatty revealed years later. “My master was, to my knowledge, the father of eleven slaves. But did the mothers dare to tell who was the father of their children? Did the other slaves dare to allude to it, except in whispers among themselves? No, indeed! They knew too well the terrible consequences.”

When Hatty learned that her master was building a cottage outside the town, just so that he could have a secret place to take her, she knew it was time for action. What she did to protect herself may seem odd now, but her options were limited, so she relied on cleverness and courage. Rather than become an unwilling victim of Dr. Norcom’s lust, she started a relationship with another white man in town, Sam Sawyer. He was a friend of her family who would be kind, and possibly even help her to freedom. Hatty did not confide in her grandmother, knowing the old woman would find this choice difficult to accept, but her secrecy ended when she became pregnant.

Hatty had been hoping that Dr. Norcom might be angry enough to sell her when he heard the news, allowing her new beau a chance to be the buyer, but she had underestimated his determination. The law stated that as long as a mother was enslaved, any child born to her was a slave as well. The doctor soon had a new, baby boy slave, named Joseph, after Hatty’s uncle. The only good outcome was that Hatty, mother of a newborn, had a little time before the harassment was renewed.

For those slaves not willing to succumb to abuse and humiliation, there were only two possibilities: to fight back, or to run away. Fighting back took many shapes. Hatty tried to outsmart her master. Others decided that only violent action could change anything.

When Hatty was a teenager, a slave named Nat Turner, in the neighboring state of Virginia, led an uprising that resulted in the deaths of fifty-five white people. Patrols, or “musters,” were established—groups of white men acting as an unofficial police force, to watch, follow, search, and plunder the homes of African Americans. One of the things they were looking for was books or printed paper of any kind.

Hatty learned that her grandmother’s house would be searched by the patrols. She knew that “nothing annoyed them so much as to see colored people living in comfort and respectability.” Deviously, she worked all day to make the house clean and lovely. “I arranged every thing in my grandmother’s house as neatly as possible. I put white quilts on the beds, and decorated some of the rooms with flowers.” Perhaps the flowers irked the patrolmen, but the discovery of books and papers led to Hatty being roughly questioned.

When Hatty was nineteen years old, she informed Dr. Norcom that she was pregnant for the second time.

“He rushed from the house, and returned with a pair of shears. I had a fine head of hair; and he often railed about my pride of arranging it nicely. He cut every hair close to my head, storming and swearing all the time.”

Despite the protection offered by the baby’s father, Sam, the doctor kept his anger burning throughout the pregnancy, even hitting Hatty, and often hurling verbal abuse.

“When they told me my new-born babe was a girl, my heart was heavier than it had ever been before. Slavery is terrible for men, but it is far more terrible for women.”

Hatty had just delivered baby Louisa into Doctor Norcom’s official possession. She was permitted to live with the baby for two years at her grandmother’s house before the doctor offered Hatty a choice: become his mistress and live in comfort, or be banished to his son’s plantation. “Junior” was preparing his estate to welcome his new bride after their upcoming wedding, so Hatty’s labors would be heavy. Much to the doctor’s irritation, she chose the plantation, leaving her children behind. “I had many sad thoughts as the old wagon jolted on.”

Hatty now toiled by day and took what was known as a “slave’s holiday” at night—walking six miles across unlit fields to see her family for a few precious minutes before walking back in the dark to her quarters. This routine came to an abrupt end when she heard that her children were to arrive on the plantation the next day “to be broke in,” meaning that the doctor’s new plan was to make Hatty watch, helplessly, while her children suffered as field workers.

That night, Hatty was stirred to serious action: “At half past twelve I stole softly down stairs. I stopped on the second floor, thinking I heard a noise. I felt my way down into the parlor, and looked out of the window. The night was so intensely dark that I could see nothing. I raised the window very softly and jumped out. Large drops of rain were falling, and the darkness bewildered me. I dropped on my knees, and breathed a short prayer to God for guidance and protection …”

She went first to say good-bye to her grandmother and to kiss the sleeping Joseph and Louisa. “I feared the sight of my children would be too much for my full heart; but I could not go into the uncertain future without one last look …”

In fact, she would kiss her children only once again during the next many years.

In her book, Hatty did not name the friend who bravely sheltered her for the next few days, but one night, she wrote, “my pursuers came into such close vicinity that I concluded they had tracked me to my hiding-place.” She flew into a thicket of bushes behind the house. Crouching there, she was bitten by a poisonous snake and barely staggered back to safety. Her friend applied a poultice of warm ashes and vinegar, which relieved the pain somewhat, but Hatty knew a better hiding spot was needed.

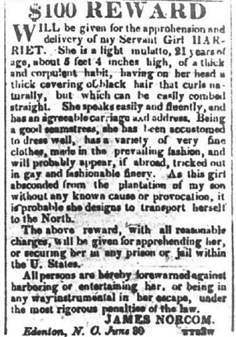

“The search for me was kept up with more perseverance than I had anticipated.” Doctor Norcom posted notices all over the country, offering a reward in return for Hatty’s capture.

Help appeared as if in answer to Hatty’s prayers. The kind wife of a local slave-owner asked Hatty’s grandmother if she could help, on condition that she never be named. Molly apparently trusted and confided in her. Hatty later wrote, “I received a message to leave my friend’s house at such an hour, and go to a certain place where a friend would be waiting for me. As a matter of prudence no names were mentioned. I had no means of conjecturing who I was to meet, or where I was going …”

Hatty’s destination was the woman’s spare bedroom, which was used for storage and kept locked. Only the mistress and cook knew she was there. But Dr. Norcom was furiously seeking revenge. It was in his power to imprison Hatty’s family in order to force them to tell where she had gone. Hatty’s son, Joseph, and little daughter, Louisa, watched over by their Uncle John and an old aunt, were all placed in the town jail. The doctor rightly guessed that Hatty would be tempted to risk her own safety to visit them in secret. But she got a note from her brother pleading with her to remain hidden: “ ‘Wherever you are, dear sister, I beg you not to come here. We are all much better off than you are. If you come, you will ruin us all …’ ” Hatty forced herself to trust that her brother and aunt would care for the children.

She soon had another fright. The doctor’s voice echoed through the house where she was concealed in an upstairs room. Dr. Norcom was rushing off to New York City because he’d heard a rumor that Hatty had been seen there, but first he was asking to borrow five hundred dollars from the very woman who was hiding Hatty!

Norcom’s trip was a failure, of course, and he returned in debt. He received an offer from a slave trader, unaware that the man had been hired by Sam Sawyer, the father of Joseph and Louisa. The trader proposed to pay Dr. Norcom $900 for Hatty’s brother, and $800 more for her two children. The doctor needed money and made the sale, making Hatty as happy a woman as a fugitive slave could be: “The darkest cloud that hung over my life had rolled away. Whatever slavery might do to me, it could not shackle my children.” The trader honored his agreement to deliver Joseph and Louisa back into Molly’s loving care, much to Dr. Norcom’s angry frustration.

As it turned out, many years would go by before Hatty’s optimistic hope of truly free children became a reality. For now, however, their safety gave Hatty strength when she was spotted by a curious servant and forced to move quickly out of the refuge of the spare bedroom. Arrangements were made for her to hide on a boat overnight. “Betty,” a friend and fellow slave, brought her a disguise—the jacket, trousers, and hat of a sailor—and then coached her. “ ‘Put your hands in your pockets and walk rickety, like de sailors,’ ” she said.

Walking “rickety” was not difficult; her weeks of inactivity, combined with fear, must have made Hatty’s legs feel pretty shaky on her way to the wharf.

“I was to remain on board till near dawn, and then they would hide me in Snaky Swamp till my uncle Phillip has prepared a place of concealment for me.” Ever since being bitten, Hatty was horrified by snakes. For the following week, she hid on the boat each night but spent her days in the swamp with her loyal friend, “Pete.” “I saw snake after snake crawling around us.… But even those large, venomous snakes were less dreadful in my imagination than the white men in that community called civilized.”

When her new hiding spot was ready, she blackened her face with charcoal and dressed again in the sailor disguise. Walking through town, she passed close by her old sweetheart, Sam Sawyer, but he did not recognize her.

“ ‘You must make the most of this walk,’ said my friend, Peter, ‘for you may not have another very soon.’ ” It would be nearly seven years before she walked that street again.

What Hatty’s uncle had set up for her was a crawl space over her grandmother’s storage shed, above the room and under the roof. It was nine feet long, seven feet wide, and little more than three feet high at its peak, with a steeply sloping ceiling. Between her and the sky were shingles; between her and the storeroom below was a mat on a rough board floor, a trapdoor, and a million tiny red insects. It was utterly dark inside, day and night. Her uncle had left behind a gimlet, a small hand tool for boring holes through wood. When she guessed from sounds that it was evening, Hatty patiently and repeatedly drilled through her wall until she had made a hole one inch across. This was her tiny window for light, air, and occasional glimpses of her precious children.

In Hatty’s book, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, seven years pass by in fewer than fifty pages. But, “O, those long gloomy days with no object for my eye to rest upon and no thoughts to occupy my mind, except the dreary past and the uncertain future!”

Hatty’s grandmother kept her fed with both food and news: the ongoing chase, family gossip, and the preparations for Christmas. Molly brought Hatty material so that she could sew clothes and toys for the children by the beam of her tiny window. During the winters, it got icy-cold in the attic. Hatty recalled that her “limbs were benumbed by inaction, and the cold filled them with cramp. I had a very painful sensation of coldness in my head; even my face and tongue stiffened, and I lost the power of speech.”

As the months and then the years passed by, Hatty watched and listened to her children growing up. Although they missed their mother, their grandmother tended them with close attention, while the lives of the surrounding adults were slowly unfolding.

Dr. Norcom went again to New York to look for Hatty. Sam Sawyer ran for Congress and won. Despite his promise, made years ago, Sam still had not freed his children. Although it may now seem odd that a white father would officially possess his own darker-skinned children, it was acceptable in that time and place. As a congressman, Sam made plans to leave North Carolina, taking Hatty’s brother, John, as his personal slave. Hatty knew Sam would stop by her grandmother’s house to say good-bye and to leave instructions regarding Joseph and Louisa. This rare opportunity to meet him compelled her to take a huge risk.

As Hatty tells it in her book, she crept down through the trap door, her weakened ankles barely supporting her. She hid behind a flour barrel until she had a chance to speak to him. He was shocked to see her there, but renewed his vow to liberate their children. He told her he’d do his best to purchase her, as well.

Hatty was now inspired to use writing as a tool in building the life she dreamed of. She again climbed down from her attic, this time to meet with her old friend “Pete,” to convince him to help in her plan. She wrote a letter to Dr. Norcom, from a made-up address in the North, pretending not to know that he’d already sold her children, and asking to buy them. “Pete” was to arrange to have the letter mailed from somewhere in New York, using a “trusty seaman” as the postman. She enclosed a misleading note to her grandmother in the same envelope, knowing that the doctor would read it.

As Hatty anticipated, her furious master slammed through Molly’s door just a few days later. Hatty positioned herself to listen to the outcome of her maneuvers. But, instead of reading what she’d written, the doctor substituted a phony letter claiming that Hatty was ashamed of running away and was asking her grandmother if she could come home. Dr. Norcom tried to trick Molly into encouraging Hatty’s return this way. This was a turning point for Hatty. As a present-day biographer put it, “She no longer felt herself Norcom’s victim, but his enemy.” Being his enemy meant that she felt she could fight back. Her writing had given her a power she’d never had before. She started a campaign to enrage and confuse the doctor, having a steady stream of letters sent from as far away as Canada.

Hatty also began to climb down often into the storeroom, to exercise and strengthen her legs. She was going to need them for what she had in mind.

Meanwhile, her brother John had escaped while serving Sam Sawyer in New York. Sam had a new wife, a white woman named Lavinia, and a new baby, Laura. Hatty’s next worry came when Lavinia met Hatty’s children and wished to adopt them!

Hatty jumped on an offer to send Louisa north to see Sam’s family instead, hoping the child would have brighter prospects. The night before her daughter left, Hatty sneaked into Louisa’s room, to introduce herself and to spend the last few hours together. She swore the girl to secrecy as they shared a memorable reunion before parting, “with such feelings as only a slave mother can experience.” Not long after Louisa’s departure, Hatty heard that her daughter had been “given” as a gift to Sam’s cousin. Once again, Sam had failed to free his children.

In January of 1842, Hatty’s cousin, called “Fanny” in her narrative, was sold to a local man. Her four daughters were auctioned off to the master of a distant estate. “Fanny” was devastated, and ran away, but found concealment close by Molly’s house on King Street. Hatty had a fellow fugitive, even if she couldn’t see her. Throughout all the ups and downs in Hatty’s life, she remained huddled in her gloomy crawl space, fervently envisioning and patiently praying for an opportunity to change her circumstances. Finally, “the faithful friend who had helped her survive in the swamp appeared at Molly’s door with word of a ship that could prove a means of escape to free soil.”

Despite the heartbreak of leaving her son, and as unnerving as this must have felt, Hatty was determined to seize the chance. But then word came of a captured runaway slave who had died painfully after a vicious whipping. This tragic news so distressed her grandmother that Hatty faltered. She allowed her cousin, “Fanny,” using the agreed-upon false name of “Linda,” to be a substitute in her place on the ship northward.

Rain and rough water kept the boat in the harbor for three extra days. Was it good luck or bad luck that Molly forgot to lock the door of her house while Hatty was downstairs with her? They were disturbed, and Hatty was sighted. Molly immediately changed her mind and urged her beloved granddaughter to leave on the boat, knowing that she’d likely never see her again.

Hatty spent the evening hours with her son. They had not spoken to each other in seven years, but he swore that he knew she’d been there, and often misled her pursuers on purpose. Together with Molly, they knelt for a final prayer before Hatty said farewell.

Even when writing her memoirs ten years later, Hatty avoided giving any details of her escape. But she wrote that after lying down for most of seven years, “I never could tell how we reached the wharf. My brain was all of a whirl, and my limbs tottered under me.”

Once on the boat, Hatty was taken to a cabin where she found her cousin. The kind captain was confused, now having two “Linda”s in hiding. He had to warn them to hush the noise of their delighted reunion.

Hatty vividly remembered her first morning on board: “O, the beautiful sunshine! The exhilarating breeze! And I could enjoy them without fear or restraint. I had never realized what grand things air and sunlight are till I had been deprived of them.”

Having “Fanny” aboard with her meant that they could share the joy, as well as the anxiety, of facing a world often imagined but without any grasp of its reality.

When the boat arrived in Philadelphia, “Fanny” and Hatty took their first steps as free women, and Hatty set out on her very first shopping trip. “I found the shops and bought some double veils and gloves for Fanny and myself.” She did not understand the money, or the price the shopkeeper named. Not wanting to appear obviously a stranger, she offered a gold coin and then counted her change to calculate the value of the items she had purchased.

Hatty and “Fanny” were greeted by a black man, the Reverend Jeremiah Durham, who was a representative of the General Vigilance Committee in Philadelphia. He, and particularly his wife, provided a warm and informative welcome to the free world. Hatty stayed with the Durhams in their little house on Barley Street, slowly absorbing new sights and ideas. “One day she took me to an artist’s room and showed me the portraits of some of her children. I had never seen any paintings of colored people before, and they seemed to be beautiful.”

After a few days, Hatty continued to New York City, where she found her own beautiful daughter, seemingly once more betrayed by Sam Sawyer. Louisa, now nine, had not been sent to school as promised and was working as a waiting-maid.

Hatty’s dream was to have a little home where she might be with her children after so many years apart. But first she needed to get a job and earn a living—without having to provide a reference from a former employer. She was eventually hired by Mrs. Willis, as a nurse for her new baby. It seemed that Hatty should now be more settled, but the next several years were full of drama, including the arrival of her son from Edenton, the death of Mrs. Willis and remarriage of Mr. Willis, a year of living abroad in London, England, and continued efforts on the part of Dr. Norcom to reclaim his valuable “possession.”

In 1850, eight years after Hatty’s flight from Edenton, there came another setback for escaped slaves living in New York and elsewhere in the North. A new law, called the Fugitive Slave Act, proclaimed that if a runaway were discovered, even in a state that did not permit slavery, that slave could be dragged back to his or her owner and punished as the owner saw fit. This law reintroduced fear into every minute of Hatty’s day. “I was, in fact, a slave in New York, as subject to slave laws as I had been in a Slave State. Strange incongruity in a State called free!”

Finally news came that Hatty had longed to hear. Dr. Norcom had died. “I cannot say, with truth, that the news of my old master’s death softened my feelings towards him. There are wrongs which even the grave does not bury.”

Respite from his pursuit was short-lived. Norcom’s daughter still considered Hatty desirable property. According to Mrs. Horniblow’s questionable will, Mary Matilda and her husband, Daniel Messmore (called “Mr. Dodge” in the book), were Hatty’s actual “owners.” They were now estranged from the Norcom family and in desperate need of money. They wrote to Hatty, smoothly asking that she either return to work for them or pay them to purchase herself.

In those days, every visitor to the city was announced in the newspaper. Hatty scrutinized the daily listings for the name she feared. One morning she came into the kitchen just as the servant boy was lighting the fire, using the newspaper as kindling. Hatty snatched the paper away from the flame, and yes, that was the day when the dreaded arrival was announced.

Hatty’s employer, the second Mrs. Willis, told Hatty to take her baby, Lilian, with her into hiding, knowing that the pursuers would be forced to return the baby to its mother should Hatty be captured. This would provide a little more time to find a solution. After a couple of anxious days, Hatty received a note from Mrs. Willis telling thunderous news in just a few words: “I am rejoiced to tell you that the money for your freedom has been paid to Mr. Dodge. Come home tomorrow. I long to see you and my sweet babe.”

Hatty was torn between profound gratitude and disgust. “My brain reeled as I read these lines. A gentleman near me said, ‘It’s true; I have seen the bill of sale.’ The bill of sale! Those words struck me like a blow. So I was sold at last! A human being sold in the free city of New York!”

When Hatty wrote her book in 1852, she did something that no one before her had had the courage to do; she discussed quite honestly how young enslaved women were repeatedly mistreated. “If God has bestowed beauty upon her, it will prove her greatest curse. That which commands admiration in the white woman only hastens the degradation of the female slave.”

Hatty resisted writing her history until after she turned forty. Her anger burst through onto the page, aimed at Americans in the northern states who she felt had ignored the plight of slaves for decades. “Why are ye silent, ye free men and women of the north? Why do your tongues falter in the maintenance of the right? Would that I had more ability! But my heart is so full and my pen is so weak!”

Hatty ended her book with the chapter about her liberation, but she lived until she was eighty-four years old. The world around her underwent many profound changes during her lifetime. She was alive to witness the Civil War, where slavery was a central issue in the conflict between the northern, “free” Union states and the southern, slave-holding Confederate states. And she was alive to greet Abraham Lincoln’s significant proclamation that would end slavery in the United States of America.

Hatty worked tirelessly throughout the war and for the rest of her life, helping refugees, organizing medical care for freed slaves, raising money to build an orphanage, and teaching. She continued to come up against white people with prejudice, as she would still if she were alive today. But her trials had taught her that “I can testify, from my own experience and observations, that slavery is a curse to the whites as well as to the blacks.”

Perhaps most importantly, Hatty and her daughter together founded a school called the Jacobs Free School, where she could be certain that African-American children would learn to read and to write.

Harriet Jacobs watched her children, and seven passing years, through a tiny peephole. Although her view was constricted, her writing addressed the enormous issues of freedom and truth. And her vision of heaven was a small, tidy home where she could live with her children.

Meanwhile, in England, Isabella Beeton staged a quiet revolution of her own. She believed that women who created an orderly home for their families were providing unequaled leadership and nurturing. Her writing changed the domestic world forever.

Isabella Beeton and Harriet Jacobs each published her book in the same year, 1861.