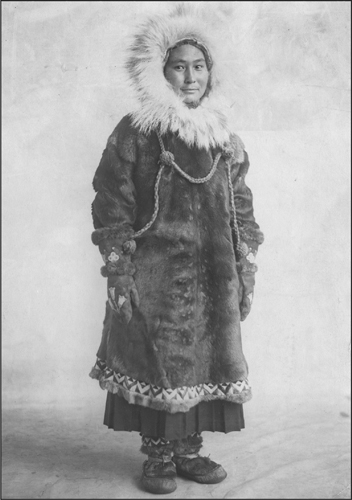

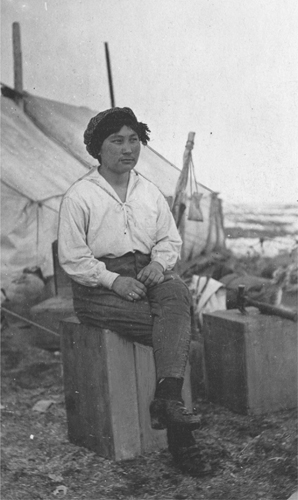

Ada Blackjack

1898–1983

One day just after I had cleaned my second seal I heard a noise like a dog … and I looked out the door and about fifteen feet from the tent was a big bear and a young one. I was very scared but I took my rifle and thought I would take a chance. I knew if I just hit them in the foot or some place where it would only injure them a little they would come after me, so I fired over their heads …

Ada Blackjack was more afraid of polar bears than anything else—including being alone on a remote island north of Russian Siberia with a dead man in the next tent. She had never held a rifle before she went north, but she learned to use one when her survival depended on it.

Ada is sometimes referred to as the “Heroine of Wrangel Island,” although she certainly did not set out to do anything heroic. She was hired, under shady pretenses, to be the seamstress on a secret expedition in the Arctic. With four men, seven sled dogs, and one kitten, she traveled to desolate, windswept Wrangel. Two years later, a rescue ship found Ada alone, all her companions dead or disappeared. Despite the harrowing adventure, and her lack of formal education, Ada kept a journal for the last several months of her ordeal, telling her side of the story.

Ada Delutuk, an Inupiat Eskimo, was born in 1898, the same year that gold was discovered in her home state of Alaska, and the same year that Robert Peary set out on his second expedition to the Arctic pole. She grew up in the tiny settlement of Spruce Creek. (When Ada was alive, the word used for her people was Eskimo, so that is what will be used here.)

When she was sixteen, Ada married a man named Jack Blackjack. She had three babies with him, but only one, a son named Bennett, lived past infancy. Ada’s marriage ended after six years, leaving her with no support and a sick little boy. Bennett had tuberculosis and needed a doctor’s care. But doctors cost money, and Ada had none. She placed her son in an orphanage, where he could be cared for while she found herself a job.

Eventually, Ada found work as a housecleaner, earning barely enough to pay for her own expenses. She was on her way home one evening, feeling blue after a long day, when she was stopped by the local police chief, who was an acquaintance. He informed her that Eskimos were being recruited for an expedition to the north. He knew that Ada’s superior abilities as a seamstress would be an important qualification.

Staying warm and dry in the Arctic was a matter of life and death; the success of any mission to the far north relied on having animal skin clothing properly constructed and repaired to protect against bitterly cold winds and icy waters. The seams were carefully rolled and stitched to remain watertight. The sewing needle was the most essential tool used by the Eskimo people.

Ada didn’t like the idea of being so far away from her son, but they were promising what seemed like a vast amount of money: fifty dollars a month! There would be other Eskimos on the trip, she was told. The men would hunt to provide food for the scientists, the women would sew the necessary fur garments, and they’d all come home rich.

The expedition was the idea of a man named Vilhjalmur Stefansson, a dashing Canadian of Icelandic heritage. He was an ethnologist as well as an explorer, meaning that he studied the culture and customs of various ethnic groups. He had lived in the Arctic for two years, learning to hunt and live as the northern natives did, and he’d written and published a book called My Life With the Eskimos.

In 1910, Stefansson discovered a previously unknown tribe of fair-haired Eskimos, who still used primitive tools. He conjectured that they were of Viking descent, though that idea has since been disproved. He believed passionately that the Arctic was not a bleak wasteland, but that it could be settled by white men, particularly those willing to live off the land, as the natives did.

Stefansson’s public reputation was shaky, however, and with good reason. He had been commander of an earlier Arctic expedition sponsored by the Canadian government, and had abandoned his ship when it became trapped by ice. The ship eventually was crushed and sank. The men on it were lost, while Stefansson and two others proceeded by sledge across the frozen oceans, surviving for ninety-six days on what he could shoot with his rifle.

Stefansson was convinced—correctly, as it turned out—that the North Pole lay in the center of an undocumented continent. But his dream was not to pursue the location of the pole. He wanted to secretly claim land—already Russian territory—for Canada and the British Empire. His objective was a place called Wrangel Island.

Ada went to visit a shaman, who confirmed that she would go to the island, but that “death and danger” waited there. Despite this warning, Ada accepted the job. Her need for money to look after Bennett outweighed the stomach-churning worry.

She was given an allowance to buy supplies: needles, sinew, thread, and thimbles, which were used to protect the fingers when stitching through heavy material like animal hides. She also bought towels and handkerchiefs, and one precious Eversharp pencil. In 1921, Eversharp pencils were a recent invention; the first mass-produced mechanical pencils, they featured a mechanism that propelled a strand of lead into the writing shaft, and so they never had to be sharpened. They were so popular that the company was manufacturing 35,000 every day. Ada treasured hers above almost any other possession.

Stefansson was not leading the venture this time. Between dates on a successful lecture tour, he would live in New York. He had hired four young men to represent his interests in the Arctic: Lorne Knight and Fred Maurer, who had been with him on a previous excursion; Milton Galle, from Texas; and Allan Crawford, a fellow Canadian, designated leader so that he could be the official claimant of Wrangel Island, under Stefansson’s direction.

The men met Ada in Nome, Alaska, in September of 1921, when they arrived on the boat Victoria. The steward had presented them with a good luck kitten, soon named Vic. Their destination was undisclosed, because Stefansson wanted the small colony in place before word of his intentions leaked out. The newspaper reporters who followed them about assumed they knew a secret source of gold, left over from the gold rush years before.

The other Eskimos who had been hired did not show up for departure. Ada was assured that an Eskimo family would join the party at the next stop. Reluctantly, she boarded the Silver Wave, bound for the unknown.

In East Cape, Siberia, the Russian governor was suspicious about the purpose of this mission, but laughed when he heard the destination. Why would anyone go there?

He warned them to respect the fact that Wrangel Island was Russian territory. Far more worrisome to Ada was that no local Eskimo was willing to come along. Despite her dismay, Ada thought about the money and allowed herself to be talked into going.

On September 16, 1921, after a stormy crossing, the Silver Wave deposited five people, eight animals, and small mountains of equipment on a bleak and windy beach. While Ada watched the parting ship with a mournful heart, the four men unfurled the British flag and claimed the island on behalf of King George V.

The plan was to stay on Wrangel Island for two years, but they brought with them supplies for only the first six months of winter. Part of the experiment was to “live off the land,” hunting and fishing for food as the Eskimos did. However, they had failed to purchase one item essential for survival: the umiak, or small hunting kayak that was used for skimming through icy waters in pursuit of seals or walrus.

The first few days on site were spent building tents and setting up camp. Lorne Knight and Fred Mauer had been in the north before, but Crawford and Galle were having their first adventure in the Arctic. As for Ada, her biographer wrote that “she was barely five feet tall, unskilled, timid, and completely ignorant of the world outside Nome, Alaska. She was deathly afraid of guns and of polar bears. She knew nothing about hunting, trapping, living off the land, or even building an igloo.”

The early days of adjustment were tough. The men did not warm up to Ada, and they recorded that Ada acted a bit crazily with homesickness and panic. She developed a big crush on Allen Crawford, whose green eyes could set her mooning, causing the men to ridicule her. She seems to have suffered from something called “Arctic hysteria,” a temporary mental illness that causes the victim to be in a slump, to cry frequently, to run away, and to behave erratically. After many days and punishments from the men, Ada’s condition subsided. She resolved to pull her weight, and she became industrious and more congenial. The men began to trust her, creating the sense of a team.

As fall became winter, the colonists settled into a routine. The men each had scientific studies to make, along with the basic requirements of survival that kept them steadily occupied. Their favorite dog, Snowball, died in November, and a second one died a short while later.

There were several close calls with polar bears, who were sometimes bold enough to sniff their way right into the tent. Lorne Knight wrote in his diary that one time, “the fellows started to throw things; first the firewood, and then the pots and pans, and finally dishes. Of course, the bear was hit several times, but he was determined to come in. His old snoot was working from side to side and the digestive juices were dropping from the end of his tongue. I guess he was hungry.” That particular bear finally fled—too quickly to be shot for supper.

The long, dark weeks of winter arrived, with sixty-one days of “night” between November and January, when it was light for only about an hour out of twenty-four. The group was not prepared for the ordeal ahead. None of them had medical know-how, and so minor problems became aggravated without the proper attention. Lorne Knight made a disastrous exploratory trek into the wilderness during the spring of 1922, and nearly died when he had to swim across the frigid Skeleton River to get back to camp.

As summer approached, they looked forward to the arrival of the promised ship, carrying a stock of food, ammunition, and materials. There was a narrow access period during the summer months when a ship could pass through the ice-choked Chukchi Sea. Ada, especially, resolved to take the opportunity to escape from Wrangel Island, and return to her mother and Bennett.

Unbeknownst to the waiting group, Stefansson’s efforts had been held up by a lack of funds, and perhaps an attitude that renewed provisions were not crucial. Stefansson, the optimistic Arctic-lover, was fond of saying things like, “I think that anyone with good eyesight and a rifle can live anywhere in the Polar Regions indefinitely.”

Relief was sent too late. Captain Bernard, on board the Teddy Bear, tried valiantly to cut through the frozen waters north of Siberia, but “the report was grim—nothing but a solid wall of ice across the horizon in the direction of Wrangel Island.” Heartsick, he was forced to turn back.

“The boys expected a boat up until the last of October,” said Ada. “Around about November they knew the boat wouldn’t come.”

Stefansson was not particularly worried that he’d left arrangements for relief too late and that “his” expedition was stranded for at least a year past their expectations. “This means merely that the men on the island are cut off from communication for a year,” Stefansson wrote to Milton Galle’s mother. “They are just as safe on their island as Robinson Crusoe was on his—a little more so because there are no cannibals in that vicinity.” His overconfidence—some would say negligence—would prove to be fatal.

The colonists on Wrangel Island were eating their way through the pieces of a walrus, even the flippers, which were difficult chewing. Slowly came the dismal realization that the ice had closed in, making the arrival of a relief ship impossible. They were sentenced to a second miserable winter.

“At Christmas time we had some salt seal meat and some hard bread and tea for our Christmas dinner,” Ada said later. “I wondered where I would be if I lived until next Christmas.” Though wildlife had seemed abundant when they’d first arrived, it became dramatically scarcer and had not reappeared in the spring as anticipated, meaning they’d not been able to dry and salt much reserve food.

In desperation, in January of 1923, Knight and Crawford set out with the five remaining dogs, intending to walk across the ice to Siberia. If all went well, it would take sixty or seventy days to reach civilization, and as many again to return with fresh supplies. They left farewell letters to their families in camp, in case some disaster prevented their return. Only a week later they were back. January was the deadliest month in the north, dark for about twenty hours each day. They had been thwarted by a blinding blizzard, and Knight’s weakening health had quickly worsened when faced with the grueling physical demands of hiking in the Arctic.

They quickly decided that Knight should remain in camp with Ada, and the other three men would make the trek instead. It was their only hope. While preparations were made that week, they measured temperatures as cold as fifty-six degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

On January 28, Crawford, Mauer, and Galle left for Siberia. They took their diaries but Galle left his typewriter, telling Ada firmly not to touch it in his absence. Again, each wrote a farewell letter to his family. They took all the dogs, leaving Vic the cat with Ada and Knight.

Those three men and the dogs were never seen again.

Ada “made a calendar out of typewriting paper cut into small pieces,” to help keep track of the passing days. She wrote a note in the margin saying: “Why Galle leave?” He had been a cheerful companion, the one who behaved most like a friend to Ada. His departure must have left a real hole, making Ada entirely responsible for the ailing Knight and for the upkeep of the camp.

In February, Ada found Knight collapsed in the snow and had to drag him to his bed in the tent. He finally confessed that he suspected his condition was due to scurvy. This terrible disease attacks when a person is on a limited diet and not getting the right nutrients from his food, particularly the vitamin C in fruits and vegetables. Using the encyclopedia on the expedition bookshelf, Knight began an obsessive tracking of his symptoms and what might lie ahead. He continued to write in his journal every day, and many of the available details of these weeks are thanks to his record.

Ada’s life back in Nome had not involved setting traps or shooting. She was deathly afraid of the “boam” (boom) that guns made, but soon her survival would depend on overcoming this fear.

Maurer left Ada with a map of his trap lines, so that she would know where to go each day to check for animals and to reset the traps. In the beginning, she didn’t understand how the traps worked, but after a few failures and an empty stomach, she triumphantly caught her first fox. Knight gave her a lesson in shooting the rifle, but her efforts were not impressive and Knight sneered at her.

Apart from the time that Ada spent doing the work she’d accomplished before with the help of four men, there were a few hours of each day that she and Knight now spent confined together. They realized that it made the best sense to heat only one space, so they were sharing a tent about the size of a small, low garage, with a wood-burning stove, two cots, all their food, and other supplies.

They did not have much to talk about. Knight wrote in his journal that, as a conversationalist, “she’s bunk.” But they soon had a routine of telling each other fairy and folk tales. Ada loved to hear Knight’s version of “Jack and the Beanstalk.” Her favorite story to tell was an Eskimo legend called “The Lady in the Moon,” about a young girl on a quest who takes the wrong fork in the road and comes home transformed into an old woman, with no kin left to greet her.

Knight had brought his family Bible on the expedition. Ada, already a Christian believer, pored over the colored plates and beautiful type for hours, touching the pictures with her fingers, becoming more devout.

In the middle of March, Ada began to write a journal. Each of the men had devotedly kept a log while they were on Wrangel Island, documenting scientific and personal observations, but Ada was not used to expressing herself on paper. Although her English was not perfect and she made plenty of spelling mistakes, her handwriting was clear and round, like that of a schoolteacher. Her actual, uncorrected words are reproduced here, to share the sense of her “voice.” The early entries were mostly a trapping log and a recitation of her daily chores, with occasional news of other kinds, but eventually Ada warmed up to the idea of writing more about her worries and her small triumphs.

Made in March 14th, 1923. The frist fox I caught was in feb. 21st and then second March 3 and 4th, 5th, that makes 4 white foxes …

On March 12 she trapped three foxes in one day. She made fox soup, served with raw seagull eggs. Because of his illness, Knight’s teeth were so loose in his gums that he could no longer chew and could hardly even swallow.

March 16th. I have not feeling well for three day frist I was headach and then I had stumpick trouble and today I feel much better. I was over to the traps with no fox or fresh tracks. And last night knight told me I can keep the bible he said he give them to me, very nice day so far.

The style of Ada’s writing is not literary, the content is often repetitive and mundane, but the fact that it exists at all is as miraculous as anything she might have prayed for while thumbing through Lorne Knight’s family Bible.

26th

… I haul one load of sled and saw four cuts of log and chop wood, and we look at knights legs my! They are skinny and they has no more blue spots like they use to be.

During the month of March, Ada managed to trap thirteen foxes, including one that had dragged a trap away on its foot a few days before, and returned to be trapped again. “It has caught trap by trap that funny,” she wrote.

Over the next few days, Ada suffered from an ailment that caused her eyelids and face to swell badly, leaving her unable to do the chores. She was clearly worried because on April 2 she wrote instructions, “If anything happen to me and my death is known …” She had made a black strap for Bennett’s school bag and asked that it be sent to him, “for my only son. I wish if you please take everything to Bennett that is belong to me. I don’t know how much I would be glad to get home to folks.”

Within a few days she was back to work, with her eyes much better. The main concern each day was whether the wind was blowing too hard for her to leave the tent, and whether or not the traps held a fox or two. In between checking the traps, she sewed, cut wood, melted snow for their water supply, and prepared what little food they had.

On April 21 they were still surrounded by ice and could not hope to sight a relief ship until June, when the ice began to break up. Knight must have been frustrated nearly beyond endurance, knowing what little hope he had of survival. Ada chopped wood that day but did not get out to the traps. “And when I come in and build the fire knight started to cruel with me …”

She continued with her longest entry in the diary, obviously needing to vent her sadness. Knight had said terrible things to her; he’d applauded Ada’s husband for being mean, saying that she deserved it, he’d claimed that Ada did nothing to help Knight, “And he menitions my children and saying no wonder your children die you never take good care of them. He just tear me into pieces when he menition my children that I lost. This is the wosest life I ever live in the world …”

The possibility of death was clearly on Ada’s mind. Again she wrote her “last wishes”:

If I be known dead, I want my sister Rita to take Bennett my son for her own son and look after everythings for Bennett she is the only one that I wish she take my son don’t let his father Black Jack take him, if Rita my sister live. Then I be clear.

Ada B. Jack.

The following day, she wrote: “Apr. 22. I didn’t go out today because I was just chock with cry.” Deeply hurt by the terrible scene with Knight, Ada spent much of the next few days sleeping and reading the Bible.

Apr. 29th. Still blowing I didn’t go out. And knight said he was pretty sick and I didn’t say nothing because I have nothing to say and he got mad and he through a book at me … And I didn’t say nothing to him and before I went in my sleeping bag I fell his water cup and went to bed.

May 3 provides the first sign that spring might come: “I was out to chop wood today and I saw snow bird. Oh my how I am glad to see some snow birds come …”

Knight was failing. “He was so weak that I had to hold his head to give him a drink of water. I made a canvas bag and filled this bag with hot sand to keep his feet warm, every morning and night for two months I heated this sand and put it to his feet.”

May 10, 1923, was Ada’s twenty-fifth birthday, but she didn’t mention that in her diary. She later said that she awoke to the sound of dripping and thought it was rain, or even ice thawing from the warmth of spring. But it was the sound of Knight’s nose bleeding. “He had a one-pound tea tin half full of blood,” and “his face was just blue.”

“I think he was pretty near die this morning,” she wrote. On May 12, she said, “I fry one biscuit for knight that’s all he eat for 9 days he don’t look like he is going to live very long …”

The traps were empty, day after day. Knight got weaker and sicker. Ada tended to him and stitched away, making herself warm clothes, producing a “blanked coat” and a “clothe parky.” She made herself do target practice, knowing their lives depended on it. She saw more birds every day, but flying birds are tricky targets and she had only occasional luck. On June 7, she spotted a “see gall”—a seagull—“and I took a shot at him and I got him dead shot. Oh my! It good and I eat no meat for long time …”

On June 8, Ada had another nursing duty for Knight, the unpleasant task of cutting a hole through his sleeping bag so that he could use a bedpan. She also saw fresh polar bear tracks on the beach near the camp.

On June 10, Ada needed a new journal, but what could she use for paper? Knight suggested a photographic supply order book that sat empty with their supplies. So she began a second volume, clearly restating on the first page that she was appointing her sister, Rita, as guardian of Bennett, preferred over Black Jack, his father: “I know she love Bennett just as much as I do I dare not my son to have stepmother. If you please let this know to the Judge.” She also gave directions as to where her pay from the expedition should go—to her mother, Mrs. Ototook, and to Rita to care for Bennett. She followed the official request with her signature, and the plaintive, “I just write noted in case Polar bear tear me down …”

The report on her companion that day is this: “knight is very sick he hardly talk and he is skinny my he nothing but skin and bone he lay in his sleeping bag for four month he pretty near die 10th of May and 12th…”

But there they both were, well into June. Knight was still alive, surely thanks to Ada’s care. She suffered from snow blindness that week, but still, “I found one see gall egg and that one geese I got she has one egg and two smale ones knight eat some egg he cann’t eat meat.”

She couldn’t go out for several days because of the soreness of her eyes. Then she started practicing her shooting again, determined to bring in some birds.

June 17. I wash my clothes today and I shot once to a Idars [eider duck]. and this evening I made a target and shot two times with the rifle. and I took my target in and show it to knight and he said its pretty good shooting and I saw a creek flowing to the harbar.

That entry tells us two important things: Knight had paid her the highest compliment he could—to congratulate her on good shooting. And the creek actually flowing meant that the ice was slowly breaking up.

June 21 … knight is getting very bad he looks like he is going to die.

Ada felt the situation was dire enough that she broke her promise to Milton Galle and used his typewriter:

Dear Galle, I didn’t know I will have very important writing to do. You will forgive me wouldn’t you … Mr. Knight he hardly know what he’s talking about I guess he is going die he looks pretty bad … Yours truly Mrs. Ada B. Jack

Knight died that night. Her next handwritten entry reads: “June 22. I move to the other tent today and I was my dishes and getting some wood.”

Ada did not announce Knight’s death in her diary because she made an official declaration using the typewriter:

Wrangel Island

June 23rd, 1923

The daid of Mr. Knights death. He died on June 23rd I don’t know what time he die though Anyway I write the daid, Just to let Mr. Stefansson know what month he died and what daid of the month. writen by Mrs Ada B. Jack

Later, Ada said, “I had hard time when he was dying. I never will forget that all my life. I was crying while he was living. I try my best to save his life but I can’t quite save him.”

She was now alone—except for Vic the cat—in the frozen wasteland, at least sixty days’ walk from the nearest settlement, but in which direction? Ada had no idea. All her faith had to focus on a ship making its way through the ice. The ground was too hard to bury Knight. She left him lying inside his tent in his sleeping bag. She stacked boxes around him to discourage animals and to mask the smell of his body decaying. Knight had asked her to preserve his journal, which she now protected with his camera in a box under a tarp.

Ada had no choice but to keep hunting and chopping wood and learning new tricks of survival. She even tried to make a visual record of her new solitude: “I took pictures of this tent and myself I don’t know how I work the camra.” And later, “June 25. I was taking walk over to little Island and I found three see gall eggs in one nest. And I cook them for my lunch I take tea and saccharine I had a nice picknick all by myself.”

On June 27, “I saw a seal and I went after it and got it with one shot … That’s a frist seal I ever got in my life.”

The next day she heard a funny noise, and when she looked out through the door, she:

… saw Polar bear and one cub. I was very afraid so I took a shot over them see if they would go so they went away and they were looking back and I shot five times and they run away.

July 1st. I stay home today and I fix the shovel handle that I brack this spring and I saw Polar bear out on the ice and this evening I went to the end of the sand spit shot a eidar duck I shot him right in the head thank God keep me a live till now.

The migration of seals across Ada’s beach continued to provide food and target practice, though a polar bear and cub staged a raid and stole one whole freshly killed seal. She had moments of summer, “all day very nice and sunshines,” but she never forgot that she might be there through bad weather again. She steadily dried food, knitted mittens, repaired her boots, and fixed up the structure of her tent, assembling an observation platform on stilts to improve her view. Her sewing began to get fancier; she mentions beading and wolf-fur trim, chosen for hoods because it did not freeze when breathed on.

In mid-July, Ada made herself a canvas boat, and although she had no experience in boat-building:

… it works all right this afternoon I got three old sqaws [female seals] and I use the boat I made.

July 19.… the beach got open water …

On July 24, she heard walrus, and the next night, “oh yes I dreamed I was singing three cheer for the red white and blue.”

I clean seal flappers and put them away in case ship comes so I can take them home and eat them with my sisters …

July 30.… the ice is broken to piece quite many open leads.

Early in August, her canvas boat floated away, but “I made another canves boat, better this time.” She proudly made oars, too!

Ada sighted polar bears—or their tracks—close to camp nearly every day, but her main focus was how the ice was breaking up on the water. One morning, she found that the lard can where she’d been storing her seal blubber had been emptied by a polar bear in the night. She worked hard on knitting a seal net to help her hunting. She also unraveled a sock from the dwindling supplies, to give her wool to knit new gloves.

Aug. 20. I finished my knitted gloves today and I open last biscuit box. The ice is over little below horizon. I thank the lord Jesus and his father.

That is the final entry in the diary. She awoke the next morning and heard a sound that she first assumed was a walrus. But soon it got louder. Ada scrambled to her lookout and peered through the fog with her binoculars.

A ship.

The Eskimos on the deck of the Donaldson cheered. They could see a forlorn figure through the fog and knew they were in time to save someone. The greeting was emotional. The skipper, Harold Noice, gathered a weeping Ada into his arms and carried her back to the ship.

When she had warmed up and recovered a little, Noice and Ada returned to shore to collect the only other survivor, Vic the cat, as well as Ada’s possessions and all the papers belonging to the men. The crew dug a grave for Knight and held a ceremony. Ada said good-bye to the island where she had lived for almost two years.

Noice encouraged Ada to write down her story while on board the boat, to the best of her recollection.

Although he later cast suspicion on Ada’s character, Noice, for now, was her savior. After their return, unexplained motives compelled Noice to perform several confusing acts: he tampered with Knight’s diary, he withheld documents from the grieving families, and he suggested that Ada had allowed Knight to die, or worse, had killed him.

Ada was able to convince Knight’s family of the truth and she was not formally accused. But life was never easy for her. She married a man named Johnson and had another son, Billy, but the second marriage also ended unhappily. Because she was poor and not well, Ada was obliged to put Billy and Bennett into a children’s residence for nine years. When she finally scraped together enough money, she reclaimed the two boys and worked herding reindeer. She relied on her Wrangel Island skills to feed the children by hunting and trapping. Billy eventually moved away, but Bennett continued to live with his mother.

Ada avoided publicity as much as possible. She died in May 1983, just after her eighty-fifth birthday.

Wrangel Island is now a Russian wildlife refuge, with a small scientific community and a Chukchi Inuit settlement. The animals living there are mostly the polar bears that Ada feared so much, as well as walrus and reindeer. There is still a feeling of mystery about the place because it is nearly always icebound and often drenched in a thick fog.

Allan Crawford was the young, green-eyed Canadian who disappeared on his journey across the ice to find help. During the difficult time of making decisions about her son’s papers, his mother received a letter from a friend. That letter contained this sentence: “Real history is made up from the documents that were not meant to be published.”

The story of Ada Blackjack is profound proof of that fact.

Ada Blackjack went to the Arctic to help support her young son, but she missed him terribly throughout her ordeal.

Dang Thuy Tram, separated from all familiar loved ones in wartime, also thought and wrote about her family every day that she was away.