Molecular Marker Assisted Gene Pyramiding

Jitendra Kumar*; Shiv Kumar†; Debjyoti Sen Gupta*; Sonali Dubey*; Sunanda Gupta*; Priyanka Gupta* * Division of Crop Improvement, Indian Institute of Pulses Research, Kanpur, India

† Biodiversity and Integrated Gene Management Program, International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), Rabat, Morocco

Abstract

Genomics-assisted breeding is a relatively powerful and fast approach to develop high-yielding plant varieties adapted to different environmental conditions. In lentils, the availability of molecular markers associated with agronomically important traits is limiting the use of this biotechnological tool in breeding programs. However, in the recent past, several high-density linkage maps have been developed through the use of Expressed Sequenced Tag (EST)-derived Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) markers in the lentil. These maps have recently been employed to identify the QTL linked to the gene(s) imparting tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses in lentils. Moreover, the application of the next generation sequencing (NGS) and genotyping by sequencing (GBS) technologies have facilitated speeding up the lentil genome or transcriptome sequencing projects and large discovery of genome-wide SNP markers for genetic and association mapping. These efforts have opened up avenues for marker-assisted selection in lentils.

Keywords

Molecular markers; Transcriptome; Molecular linkage map; Breeding; Lentil

7.1 Introduction

The lentil (Lens culinaris ssp. culinaris Medik.) is an important cool-season crop. It is a diploid (2n = 2 × = 14), self-pollinated crop and has a genome size of 4 Gbp (Arumuganathan and Earle, 1991). It is a rich source of dietary proteins (22%–35%), minerals, fiber, and carbohydrates. Consumption of 50 g of lentil per day helps to alleviate malnutrition, especially in developing countries. Lentil carbohydrates have a low glycemic index, so they are highly recommended by physicians for consumption by people suffering from diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases.

The production and productivity of this crop are still low due to the lentil’s poor ability to compete with weeds, its higher flower-drop rate, tendency toward pod shedding, and several other biotic and abiotic factors (Sharpe et al., 2013). Further, in recent years, sporadic changes in climatic conditions have begun to affect production and productivity in lentil cultivation.

During the past years, systematic and continuous breeding efforts have been made through conventional methods for improving productivity. However, we could not achieve substantial genetic gain, and this is reflected in the progress made in lentil productivity in India, which increased only marginally from 539 kg/ha in 1960–61 to 759 kg/ha in 2013–14 (AICRP on MULLaRP, 2014–15). One of the major reasons for this slow gain is high genotype × environment (G × E) interactions on the expression of important quantitative traits (Kumar and Ali, 2006). Therefore, recently, attention has been focused on strengthening conventional breeding programs by using new breeding tools. Now, deployment of molecular markers is routinely used world-wide in all major cereal crops and in major pulses like the common bean, chickpeas, and pigeon peas (Gupta et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2017). In the past few years, major emphasis has also been placed on developing similar kinds of genomic resources for improving the productivity of lentil crops (Varshney et al., 2009, 2010; Sato et al., 2010). In lentil marker-trait association, analysis has been established for several agronomically important traits. Use of linked molecular markers can help to provide high-yielding genotypes by improving those traits, which are otherwise difficult to improve through conventional breeding methods. This chapter discusses the present use of marker-assisted selection in lentils.

7.2 Molecular Markers

For marker-assisted selection, the variability of molecular markers is an essential requirement for developing linkage maps and identifying the markers’ close association with trait of interest. In lentils, various molecular markers such as RAPD, SSR, AFLP, and RFLP markers were developed and used in analysis of genetic diversity and construction of linkage maps (Havey and Muehlbauer, 1989, Weeden et al., 1992; Eujayl et al., 1998a). Among the various PCR-based markers, SSR markers have made significant contribution to the recent development of lentil genome maps. These markers have been developed and used in lentils (Hamwieh et al., 2009). The express-sequenced tag provided an opportunity for developing SSR and SNP markers. Therefore, Expressed Sequenced Tags (EST) have been generated through cDNA libraries in lentils (Kumar et al., 2014) and are now available in the public domain. These ESTs have led to the easy, cost-effective development of SSR and SNP markers using some special bioinformatic programs, for example, MISA for SSR detection (Thiel et al., 2003) and SNipPer for SNP discovery (Kota et al., 2003).

In recent years, second-generation technology has begun carrying out transcriptome sequencing of lentils, which permitted large-scale unigene assembly and SSR marker discovery (Kaur et al., 2011). Researchers developed a set of 2393 EST-SSR markers developed in lentils, and a subset of 192 EST-SSR markers have been validated across a panel of 12 cultivars with 47.5% polymorphism (Kaur et al., 2011). Recently, transcriptome cDNA library sequencing using the Illumina GA/GAIIx system has provided a potential alternative. As a result of transcriptome sequencing, massive data was obtained in the form of about 847,824 high-quality sequence reads and transcriptome assemblies with 84,074 unigenes.

In recent years, next-generation sequencing approaches have quickly replaced SSR markers with DNA chip-based SNP markers. About 44,879 SNP markers have been identified in lentils using the Illumina Genome Analyzer (Sharpe et al., 2013). The recent discovery of high-density SNP markers has facilitated the establishment of ultra HTP genotyping technologies such as Illumina GoldenGate (GG), which can accommodate > 1000 SNPs in GG platforms (Kaur et al., 2014; Sharpe et al., 2013). Because SNP discovery and genotyping require expensive and sophisticated platforms, the development and exploitation of SNP markers is still limited in lentils. There are techniques available to detect SNPs such as allele-specific PCR, single-base extension, and array hybridization methods. They are cost-effective methods, and through the use of allele-specific PCR (KASPar) markers, we can include a small-to-moderate number of SNPs for any specific application (Fedoruk et al., 2013; Sharpe et al., 2013).

7.3 Trait-Specific Mapping Populations

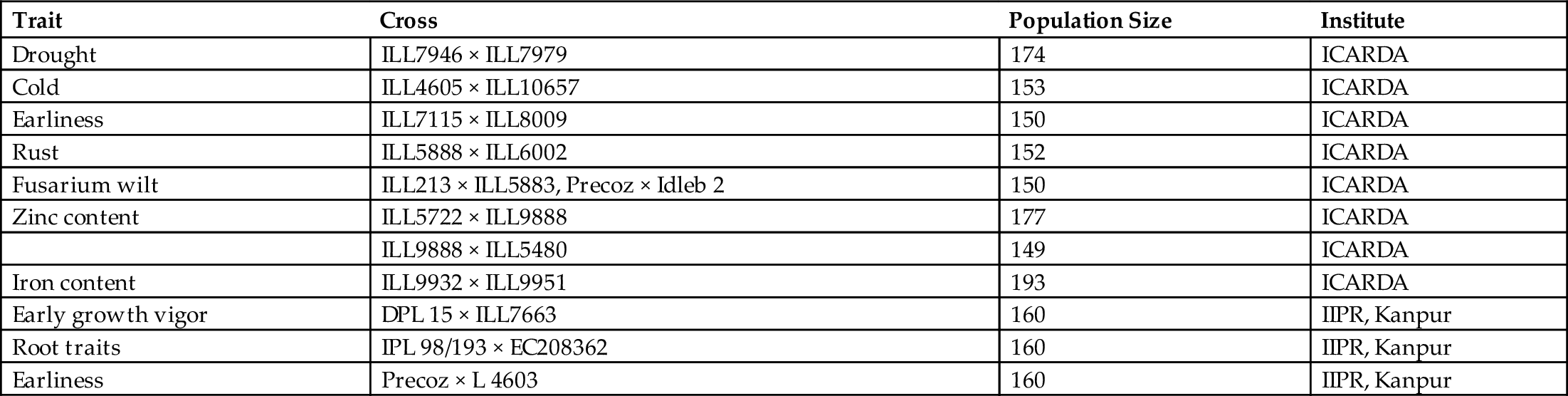

For establishing the association of marker with a trait of agronomic importance, we need bi-parental or multiparental mapping populations or a diverse panel of genotypes for association mapping. Biparental mapping populations include F2, backcross, double haploid (DH), and recombinant inbred line (RIL) populations. In the lentil, different institutions tried to develop biparental mapping populations for key traits and used them in marker trait association analysis (Table 7.1). RIL populations were developed from crosses made between contrasting parents for the traits of interest through the single-seed descent method. Indian Institute of Pulses Research (IIPR) has recently developed RIL population from a cross between ILL6002 and ILL7663 in order to identify and map early growth vigor genes in lentils. Identification of markers linked to the genes/QTLs governing these traits will help develop a genotype having high biomass at an early stage. Similarly, for tagging and mapping of genes of earliness, another mapping population was developed from a cross between Precoz (medium early duration) and L4603 (early duration). CSK Himachal Pradesh Agricultural University in Palampur, India, has developed recombinant inbred populations involving both intra- and intersubspecific crosses where parents differ for rust reaction, drought tolerance, flowering time, plant vigor, shattering tolerance, seed size, and seed weight. With rapid generation advancement technology (Mobini et al., 2014), which allows 4–5 generations per year in lentils, researchers will boost the development of much-needed genetic resources for genomics-enabled improvement.

Table 7.1

| Trait | Cross | Population Size | Institute |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | ILL7946 × ILL7979 | 174 | ICARDA |

| Cold | ILL4605 × ILL10657 | 153 | ICARDA |

| Earliness | ILL7115 × ILL8009 | 150 | ICARDA |

| Rust | ILL5888 × ILL6002 | 152 | ICARDA |

| Fusarium wilt | ILL213 × ILL5883, Precoz × Idleb 2 | 150 | ICARDA |

| Zinc content | ILL5722 × ILL9888 | 177 | ICARDA |

| ILL9888 × ILL5480 | 149 | ICARDA | |

| Iron content | ILL9932 × ILL9951 | 193 | ICARDA |

| Early growth vigor | DPL 15 × ILL7663 | 160 | IIPR, Kanpur |

| Root traits | IPL 98/193 × EC208362 | 160 | IIPR, Kanpur |

| Earliness | Precoz × L 4603 | 160 | IIPR, Kanpur |

7.4 Development of Molecular Linkage Maps

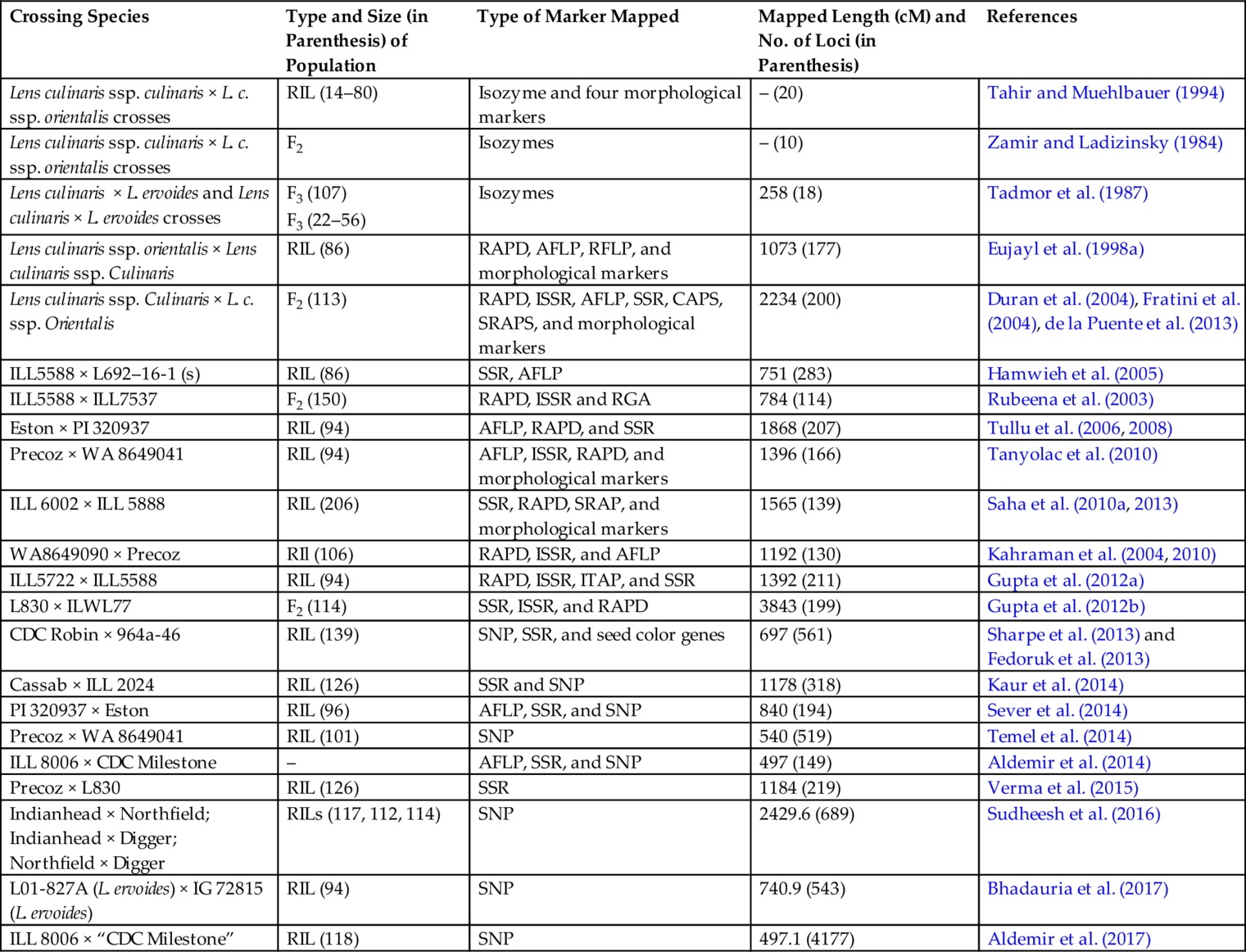

The first genetic mapping (linkage analysis) began in lentils in 1984 (Ladizinsky, 1984), and the first map comprising DNA-based markers was produced by Havey and Muehlbauer (1989). Subsequent maps were published by several researchers (Table 7.2). With the development of PCR-based markers, the number of mapped markers across the Lens genome increased dramatically (Kumar et al., 2011, 2014). The first extensive map comprised of RAPD, AFLP, RFLP, and morphological markers was constructed using a RIL population from a cross between a cultivated L. culinaris ssp. culinaris cultivar and a L. culinaris ssp. orientalis accession (Eujayl et al., 1998a). Rubeena et al. (2003) published the first intraspecific lentil map comprising 114 RAPD, intersimple sequence repeat (ISSR), and resistance gene analogue (RGA) markers. Rubeena et al. (2006) reported an F2 map comprising 72 markers (38 RAPD, 30 AFLP, 3 ISSR, and one morphological marker) spanning 412.5 cM. The first Lens map to include SSR markers was that of Duran et al. (2004). Hamwieh et al. (2005) added 39 SSR and 50 AFLP markers to the map constructed by Eujayl et al. (1998a) to produce a comprehensive Lens map comprising 283 genetic markers covering 715 cM. Subsequently, the first lentil map that contained 18 SSR and 79 cross genera ITAP gene-based markers was constructed using a F5 RIL population developed from a cross between ILL5722 and ILL5588 (Phan et al., 2007). The map comprised seven linkage groups that varied from 80.2 to 274.6 cM in length and spanned a total of 928.4 cM (Gupta et al., 2012a) used 196 markers including new 15 Medicago truncatula EST-SSR/SSR using a population of 94 RIL produced from a cross between ILL5588 and ILL5722 and clustered into 11 linkage groups (LG) covering 1156.4 cM. An inter-subspecific F2Lens linkage map consisting of 199 PCR-based markers (28 SSRs, 9 ISSRs and 162 RAPDs) mapped onto 11 linkage groups covering a distance of 3847 cM has been constructed (Gupta et al., 2012b). The population-specific linkage maps have been developed by Andeden et al. (2013), Ford et al. (2007), and Perez de la Vega et al. (2011). More recently, a map was developed from an interspecific population based on 377 SNP markers. These SNP markers have been developed using a GoldenGate genotyping array and single SNP marker assays (Gujaria-Verma et al., 2014). More recently, an intraspecific linkage map of 216 loci was constructed using three mapping populations. This map spanned a 1183.7 cM distance of the lentil genome with an average marker density of 5.48 cM (Verma et al., 2015). The list of comprehensive maps in lentils are provided with details in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2

| Crossing Species | Type and Size (in Parenthesis) of Population | Type of Marker Mapped | Mapped Length (cM) and No. of Loci (in Parenthesis) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lens culinaris ssp. culinaris × L. c. ssp. orientalis crosses | RIL (14–80) | Isozyme and four morphological markers | – (20) | Tahir and Muehlbauer (1994) |

| Lens culinaris ssp. culinaris × L. c. ssp. orientalis crosses | F2 | Isozymes | – (10) | Zamir and Ladizinsky (1984) |

| Lens culinaris × L. ervoides and Lens culinaris × L. ervoides crosses | F3 (107) F3 (22–56) | Isozymes | 258 (18) | Tadmor et al. (1987) |

| Lens culinaris ssp. orientalis × Lens culinaris ssp. Culinaris | RIL (86) | RAPD, AFLP, RFLP, and morphological markers | 1073 (177) | Eujayl et al. (1998a) |

| Lens culinaris ssp. Culinaris × L. c. ssp. Orientalis | F2 (113) | RAPD, ISSR, AFLP, SSR, CAPS, SRAPS, and morphological markers | 2234 (200) | Duran et al. (2004), Fratini et al. (2004), de la Puente et al. (2013) |

| ILL5588 × L692–16-1 (s) | RIL (86) | SSR, AFLP | 751 (283) | Hamwieh et al. (2005) |

| ILL5588 × ILL7537 | F2 (150) | RAPD, ISSR and RGA | 784 (114) | Rubeena et al. (2003) |

| Eston × PI 320937 | RIL (94) | AFLP, RAPD, and SSR | 1868 (207) | Tullu et al. (2006, 2008) |

| Precoz × WA 8649041 | RIL (94) | AFLP, ISSR, RAPD, and morphological markers | 1396 (166) | Tanyolac et al. (2010) |

| ILL 6002 × ILL 5888 | RIL (206) | SSR, RAPD, SRAP, and morphological markers | 1565 (139) | Saha et al. (2010a, 2013) |

| WA8649090 × Precoz | RIl (106) | RAPD, ISSR, and AFLP | 1192 (130) | Kahraman et al. (2004, 2010) |

| ILL5722 × ILL5588 | RIL (94) | RAPD, ISSR, ITAP, and SSR | 1392 (211) | Gupta et al. (2012a) |

| L830 × ILWL77 | F2 (114) | SSR, ISSR, and RAPD | 3843 (199) | Gupta et al. (2012b) |

| CDC Robin × 964a-46 | RIL (139) | SNP, SSR, and seed color genes | 697 (561) | Sharpe et al. (2013) and Fedoruk et al. (2013) |

| Cassab × ILL 2024 | RIL (126) | SSR and SNP | 1178 (318) | Kaur et al. (2014) |

| PI 320937 × Eston | RIL (96) | AFLP, SSR, and SNP | 840 (194) | Sever et al. (2014) |

| Precoz × WA 8649041 | RIL (101) | SNP | 540 (519) | Temel et al. (2014) |

| ILL 8006 × CDC Milestone | – | AFLP, SSR, and SNP | 497 (149) | Aldemir et al. (2014) |

| Precoz × L830 | RIL (126) | SSR | 1184 (219) | Verma et al. (2015) |

| Indianhead × Northfield; Indianhead × Digger; Northfield × Digger | RILs (117, 112, 114) | SNP | 2429.6 (689) | Sudheesh et al. (2016) |

| L01-827A (L. ervoides) × IG 72815 (L. ervoides) | RIL (94) | SNP | 740.9 (543) | Bhadauria et al. (2017) |

| ILL 8006 × “CDC Milestone” | RIL (118) | SNP | 497.1 (4177) | Aldemir et al. (2017) |

Source: This table is updated from Kumar, S., Rajendran, K., Kumar, J., Hamwieh, A., Baum, M., 2015. Current knowledge in lentil genomics and its application for crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 78.

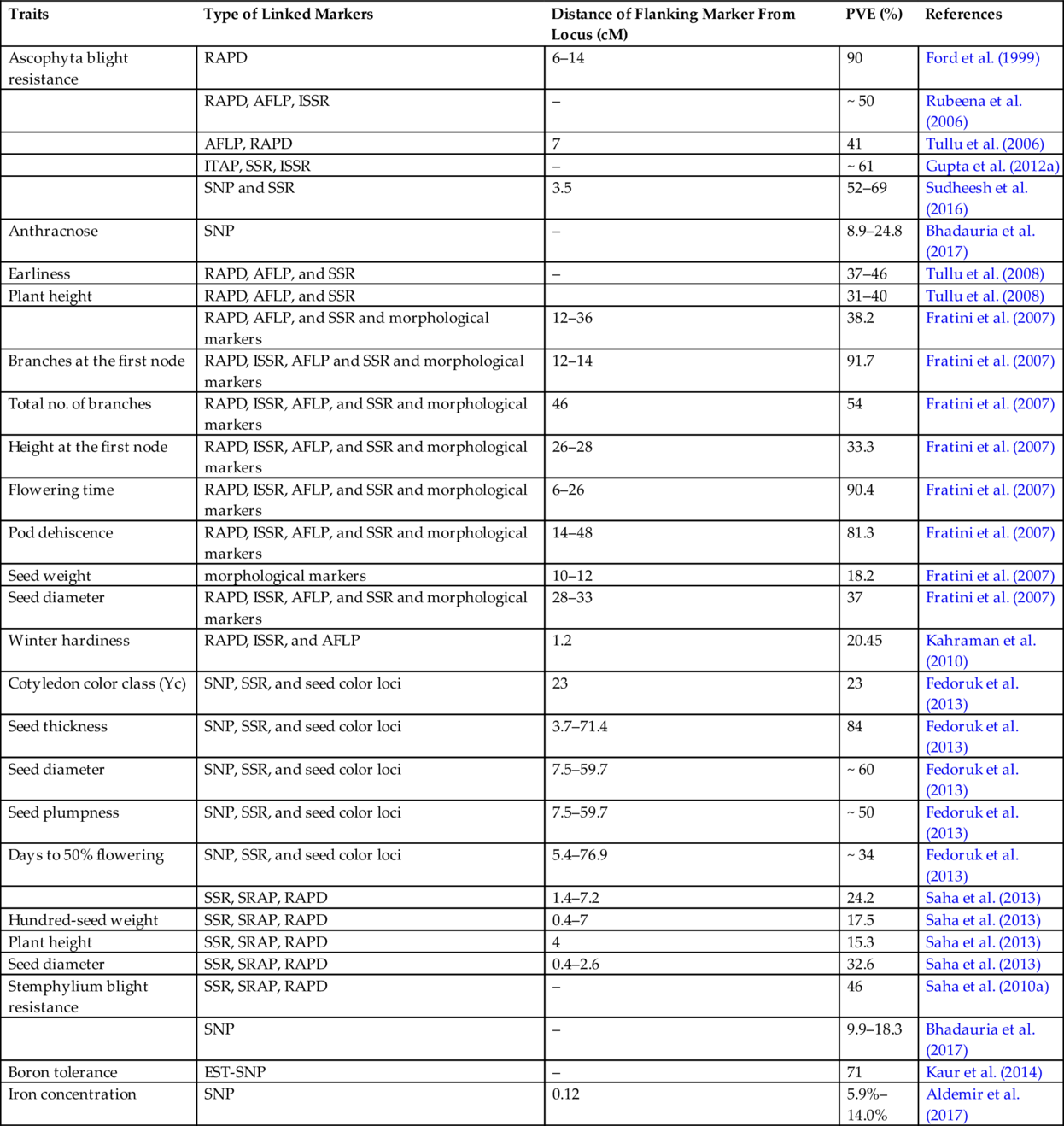

7.5 Marker-Trait Linkage Analysis (Mapping of Genes/QTL) Using Biparental Populations

In lentils, molecular markers linked to desirable genes/QTL have been identified during the past several years which have been listed in Table 7.3. However, these markers were not used in marker-assisted selection in lentils for several reasons, including poor linkage between markers and traits and low phenotypic variation explained. For example, the association between DNA markers and the Fusarium wilt-resistance (Fw) gene was confirmed by several researchers (Eujayl et al., 1998b; Hamwieh et al., 2005), but could not be used in marker-assisted selection due to the fact that the SSR59-2B marker was loosely linked with Fw at a distance of 19.7 cM (Hamwieh et al., 2005). Similarly, for several other traits, flanking markers were identified as being located at more than a 10 cM distance. Although these markers have explained high phenotypic variance, these markers cannot be used in a marker-assisted breeding program. For these QTLs, fine mapping is still required to make them useful for crop improvement in lentils. However, Verma et al. (2015) identified QTLs for the seed weight (qSW) and seed size (qSS) traits that were co-localized on LG4 and explained 48.4% and 27.5% of phenotypic variance, respectively.

Table 7.3

| Traits | Type of Linked Markers | Distance of Flanking Marker From Locus (cM) | PVE (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascophyta blight resistance | RAPD | 6–14 | 90 | Ford et al. (1999) |

| RAPD, AFLP, ISSR | – | ~ 50 | Rubeena et al. (2006) | |

| AFLP, RAPD | 7 | 41 | Tullu et al. (2006) | |

| ITAP, SSR, ISSR | – | ~ 61 | Gupta et al. (2012a) | |

| SNP and SSR | 3.5 | 52–69 | Sudheesh et al. (2016) | |

| Anthracnose | SNP | – | 8.9–24.8 | Bhadauria et al. (2017) |

| Earliness | RAPD, AFLP, and SSR | – | 37–46 | Tullu et al. (2008) |

| Plant height | RAPD, AFLP, and SSR | 31–40 | Tullu et al. (2008) | |

| RAPD, AFLP, and SSR and morphological markers | 12–36 | 38.2 | Fratini et al. (2007) | |

| Branches at the first node | RAPD, ISSR, AFLP and SSR and morphological markers | 12–14 | 91.7 | Fratini et al. (2007) |

| Total no. of branches | RAPD, ISSR, AFLP, and SSR and morphological markers | 46 | 54 | Fratini et al. (2007) |

| Height at the first node | RAPD, ISSR, AFLP, and SSR and morphological markers | 26–28 | 33.3 | Fratini et al. (2007) |

| Flowering time | RAPD, ISSR, AFLP, and SSR and morphological markers | 6–26 | 90.4 | Fratini et al. (2007) |

| Pod dehiscence | RAPD, ISSR, AFLP, and SSR and morphological markers | 14–48 | 81.3 | Fratini et al. (2007) |

| Seed weight | morphological markers | 10–12 | 18.2 | Fratini et al. (2007) |

| Seed diameter | RAPD, ISSR, AFLP, and SSR and morphological markers | 28–33 | 37 | Fratini et al. (2007) |

| Winter hardiness | RAPD, ISSR, and AFLP | 1.2 | 20.45 | Kahraman et al. (2010) |

| Cotyledon color class (Yc) | SNP, SSR, and seed color loci | 23 | 23 | Fedoruk et al. (2013) |

| Seed thickness | SNP, SSR, and seed color loci | 3.7–71.4 | 84 | Fedoruk et al. (2013) |

| Seed diameter | SNP, SSR, and seed color loci | 7.5–59.7 | ~ 60 | Fedoruk et al. (2013) |

| Seed plumpness | SNP, SSR, and seed color loci | 7.5–59.7 | ~ 50 | Fedoruk et al. (2013) |

| Days to 50% flowering | SNP, SSR, and seed color loci | 5.4–76.9 | ~ 34 | Fedoruk et al. (2013) |

| SSR, SRAP, RAPD | 1.4–7.2 | 24.2 | Saha et al. (2013) | |

| Hundred-seed weight | SSR, SRAP, RAPD | 0.4–7 | 17.5 | Saha et al. (2013) |

| Plant height | SSR, SRAP, RAPD | 4 | 15.3 | Saha et al. (2013) |

| Seed diameter | SSR, SRAP, RAPD | 0.4–2.6 | 32.6 | Saha et al. (2013) |

| Stemphylium blight resistance | SSR, SRAP, RAPD | – | 46 | Saha et al. (2010a) |

| SNP | – | 9.9–18.3 | Bhadauria et al. (2017) | |

| Boron tolerance | EST-SNP | – | 71 | Kaur et al. (2014) |

| Iron concentration | SNP | 0.12 | 5.9%–14.0% | Aldemir et al. (2017) |

Source: This table is updated from Kumar, S., Rajendran, K., Kumar, J., Hamwieh, A., Baum, M., 2015. Current knowledge in lentil genomics and its application for crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 78.

7.6 Marker-Trait Association Analysis Using Natural Diverse Population

Though, biparental mapping has resulted in the identification of a number of markers associated with genes/QTL governing traits of interest, their use in marker-assisted breeding programs is still limited because parents used for making genetic improvement might not be different for identified, targeted QTLs (Bernardo, 2008). Moreover, identification of QTLs for traits based on a biparental mapping population has also been discouraged due to poor maker-trait association and the inefficient, costly process of fine mapping (Parisseaux and Bernardo, 2004). Alternatively, association mapping (AM), which uses a set of diverse genotypes derived from known/unknown ancestry for genes/QTLs mapping, helped to overcome the disadvantage of bi-parental mapping. In association mapping, an association panel comprised of natural germplasm lines, breeding lines developed in breeding programs, individuals of multiple biparental populations, and/or populations developed by crossing multiple parents are used (Steinhoff et al., 2011; Wurschum, 2012; Gupta et al., 2014). This is cost-effective approach for QTL because phenotypic data recorded routinely on breeding lines can be used for QTL mapping. Use of diverse breeding lines in association mapping is more useful compared to other kind of diverse panels (Gupta et al., 2014). Because breeding populations are generally narrow in their genetic base, QTLs identified in the background of such populations can be used directly in marker-assisted selection, while those QTLs identified from crosses made between cultivated and wild species are useful only for the introgression of traits from exotic material (Kumar et al., 2017). However, limited efforts were used to study the marker-trait association analysis in lentils. Fedoruk et al. (2013), first used AM in lentils to identify QTLs for seed size and seed shape. As the properly designed AM panels have a greater frequency of alleles, encompassing the genetic variation of a crop, it could save both time and cost when compared to MAS in lentils. More recently, the functional markers associated with flowering time in lentils were identified through association mapping (Kumar et al., 2018).

7.7 Present Status and Future Prospects of Marker-Assisted Selection

During the past several years, significant progress has been made towards the development of molecular markers in lentils. These markers can be used for evaluation of breeding materials and introgression of QTLs/genes for economically important traits through marker-assisted backcrossing. In the following text, the present status and future prospects of using molecular markers in lentil breeding programs have been discussed.

7.7.1 Marker-Assisted Evaluation of Breeding Materials

Knowledge of the genetic diversity available in elite gene pools is required for selecting diverse parental lines for hybridization. This helps to broaden the genetic base of core breeding materials for selecting useful recombinants. In the lentil, during the past several years, the genetic diversity of the lentil germplasm has been assessed preferably using molecular markers (Udupa et al., 1999; Abe et al., 2003; Hamwieh et al., 2009; Reddy et al., 2009; Dikshit et al., 2015; Idrissi et al., 2015; Khazaei et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2016). However, these diversity analysis results could not be practically utilized for selecting parental lines in breeding programs. Use of molecular markers has helped to identify true F1 plants. In a study, use of molecular markers in lentils detected only 21% of plants were true hybrids, which enhanced plant breeders’ efficiency in selecting recombinant plants and saved the time and money required to grow a population from selfed or admixed plants (Solanki et al., 2010).

7.7.2 Marker-Assisted Backcrossing Program

Molecular markers linked to genes/QTL controlling a trait can be used to introgress that QTL in the background of improved lines through marker-assisted breeding. In lentils, although molecular markers linked to desirable genes/QTL have been reported, only those with tight association (< 1.0 cM) and high phenotypic effect can be used in marker-assisted selection (Table 7.3). For example, mapping of Ascochyta blight resistance using an F2 population derived from ILL7537 × ILL6002 identified three QTLs accounting for 47% (QTL-1 and QTL-2) and 10% (QTL-3) of disease variation. Therefore, QTLs that explained > 47% of total phenotypic variation can be used in marker-assisted breeding. Recently, QTLs conferring resistance to Stemphylium blight and rust diseases using RIL populations were identified in lentils (Saha et al., 2010a; Saha et al., 2010b). Though F2 lentil populations have been used widely in identification of QTLs, their use in marker-trait analysis has led to identification of only major QTLs. Thus, several minor QTLs were overlooked in such populations, and identification of environmental-responsive QTLs was difficult. Because quantitative traits are influenced by both genetic and environmental effects, RILs or near isogenic lines (NILs) are more suitable populations to accurately dissect their components. For Ascochyta blight, three QTLs each were detected for resistance at seedling and pod/maturity stages (Gupta et al., 2012a). Together, these accounted for 34% and 61% of the total estimated phenotypic variation and demonstrated that resistance at different growth stages is potentially conditioned by different genomic regions. The flanking markers identified may be useful for MAS and pyramiding of potentially different resistance genes into elite backgrounds that are resistant throughout the cropping season. One QTL each for the seed weight (qSW) and seed size (qSS) traits, explaining 48.4% and 27.5% of phenotypic variance, respectively, were identified in lentils. These QTLs were located on average 5.48 cM from their marker, indicating close marker-trait association, so they can be useful in marker-assisted breeding for improving seed size and weight (Verma et al., 2015). Therefore, for successful use of molecular markers in lentil breeding programs, there is a need to identify tightly linked molecular markers with genes/QTLs controlling important traits.