The Lentil Economy in India

Nisha Varghese*; Atul Dogra†; Ashutosh Sarker†; Aden Aw Hassan‡ * School of Extension and Development Studies, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi, India

† International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, South Asia & China Regional Program, New Delhi, India

‡ International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Area, ICARDA, Amman, Jordan

Abstract

Pulses are an important source of proteins, fibers, minerals, and vitamins, so they are a very important part of the human diet. Their significance in the agricultural production system lies in the fact that they are natural nitrogen fixers and help maintain soil fertility. Asia and Africa are the major producers of pulses. The share of lentils in the total pulse production has increased considerably since the 1960s. In spite of India being the second largest producer of lentils, it is also a net importer. The cost of lentil production has increased over time. The net returns on lentils are also lower than other competing crops. The domestic price of lentils has been above the international price since 2010, and the Minimum Support Prices (MSP) have remained below domestic prices. These lentil price dynamics do not favor acreage increase for the crop. To enhance domestic lentil production and productivity, targeting new niches (rice fallows), dissemination of improved production technologies, and favorable policy measures are the need of the hour.

Keywords

Pulse production; Lentil trade; Comparative economics of lentil production; Lentil prices

9.1 Introduction

Pulses have been an integral part of the human diet for centuries. Pulses, being a rich source of proteins, fibers, minerals and vitamins, are important for food security, combating malnutrition, and poverty alleviation. Due to their high nutrient density, they are also used in fortifying other foodstuffs, especially cereals. Pulses are grown in both developed and developing countries. In developed countries, they are grown in large scale, using mechanized farming, and are generally used as animal feed. In developing countries, these are grown by resource-poor small and marginal farmers, for whom pulses contribute toward household food security and serve as cash crops for income generation.

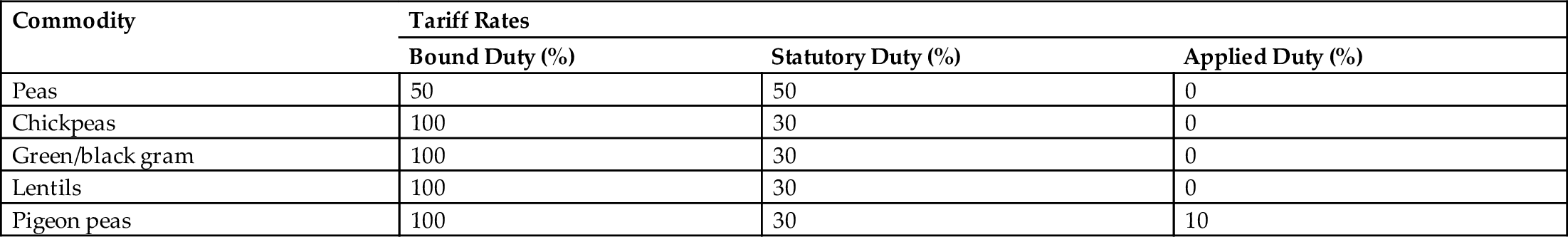

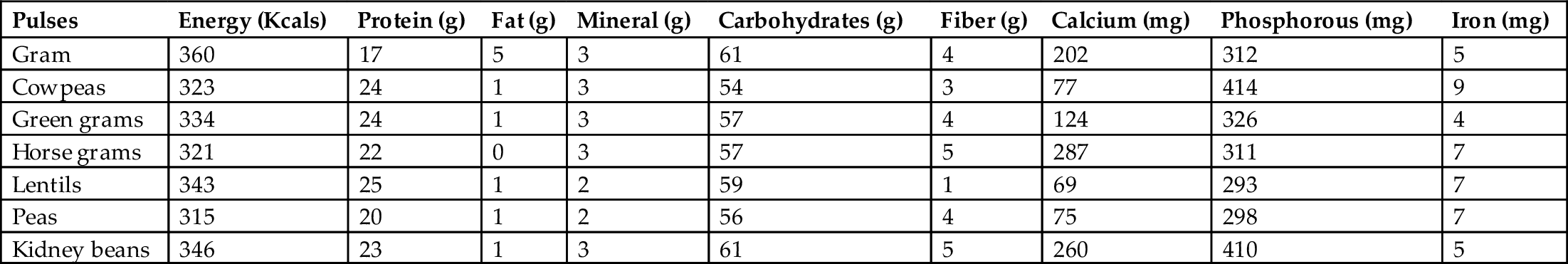

Pulses are particularly important, given that the largest number of malnourished people in the world live in India. A large percentage of Indians suffer from nutrition problems, including protein deficiency. Given the levels of poverty and prevalence of vegetarianism, ameliorating the problem of protein deficiency suggests an important place for pulses (Roy et al., 2016). With India’s large vegetarian population, pulses constitute the most common source of protein (the frequency of its consumption is higher than any other source of protein) contributing to more than 10% of protein intake. Around 89% of consumers have pulses at least once a week in India, while the corresponding number for fish or chicken/meat is only 35.4% (IIPS and Macro International, 2007). Animal source foods (ASF) are the most expensive source of protein in India, making pulses the affordable alternative. Pulses are not only important because of their nutritional value; they also enhance soil productivity and can improve the yield of other crops. With these benefits, pulses should have received adequate attention from growers, consumers, technologists, and policymakers, alike. Unfortunately, that has not been the case for pulses. Unlike cereals, the per capita urban-to-rural consumption gap for pulses has been widening over the years due to the more rapid decline in pulse consumption in rural areas (Ali and Gupta, 2012). Food-insecure farmers’ reliance upon cereal-dominated cropping systems presents a challenge to the long-term sustainability of cropping systems in developing countries (Kerr et al., 2007). India has persistently faced a deficit, and a sustainable part of domestic demand has been met by imports for over one and a half decades now. Recognizing the importance and potential of pulses for agricultural systems, nutrition, and food security, in 2013, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2016 the International Year of Pulses (FAO, 2016) (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1

| Pulses | Energy (Kcals) | Protein (g) | Fat (g) | Mineral (g) | Carbohydrates (g) | Fiber (g) | Calcium (mg) | Phosphorous (mg) | Iron (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram | 360 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 61 | 4 | 202 | 312 | 5 |

| Cowpeas | 323 | 24 | 1 | 3 | 54 | 3 | 77 | 414 | 9 |

| Green grams | 334 | 24 | 1 | 3 | 57 | 4 | 124 | 326 | 4 |

| Horse grams | 321 | 22 | 0 | 3 | 57 | 5 | 287 | 311 | 7 |

| Lentils | 343 | 25 | 1 | 2 | 59 | 1 | 69 | 293 | 7 |

| Peas | 315 | 20 | 1 | 2 | 56 | 4 | 75 | 298 | 7 |

| Kidney beans | 346 | 23 | 1 | 3 | 61 | 5 | 260 | 410 | 5 |

Source: Gopalan, C., Rama Sastri, B.V., Balasubramanyan, S.C., Narasinga Rao, B.S., Deosthale, Y.G., Pant, K.C., 2004. Nutritive Value of Indian Foods. National Institute of Nutrition, ICMR, Hyderabad.

9.2 Global Pulse Economy: An Overview

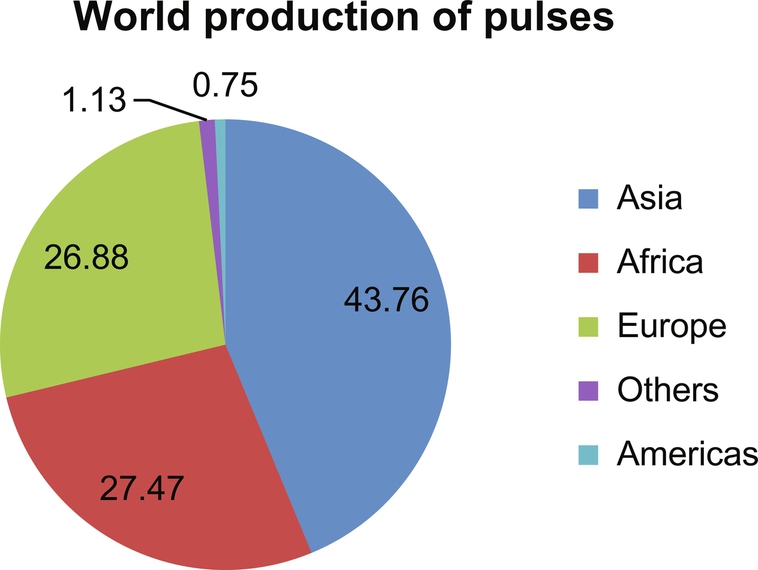

Since the 1960s, the production of pulses has made steady advances across the world. Asia and Africa account for around 70% of world pulse production (Fig. 9.1). In developing countries, pulses are grown for subsistence and are often grown as crops secondary to staples. But in developed countries, pulses are grown on an industrial scale. For the past few decades, India has continuously been the largest producer of pulses. In Asia, Myanmar increased its pulse production by more than 20-fold since the green revolution, and today, it is the world’s third largest producer of pulses. On the other hand, pulse production in China has decreased by more than half during the same period, indicating a shift in consumer preferences in favor of animal-based proteins.

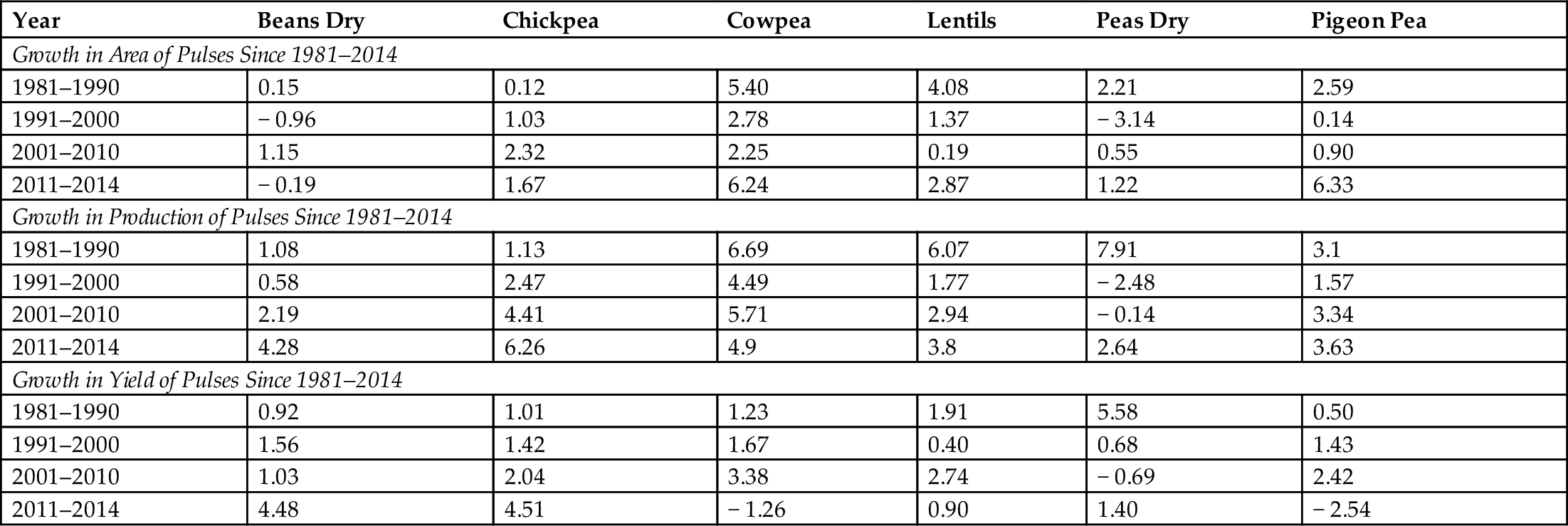

Area-based growth rates for almost all the pulses (except chickpea) declined from 1981 to 2000. The total areas sown in cowpeas and pigeon peas have shown tremendous growth in the current decade. The growth rate in area for lentils since 2011 has also considerably increased compared to the previous decades. Among pulses, the production of dry beans and chickpeas has been growing steadily over the decades. Since 1991, lentil production has grown; cowpea and dry pea production has fluctuated over the years, and pigeon pea production has grown steadily over the decades. Consumption of pulses has been declining in both developed and developing countries, probably due to consumers’ dietary preference for dairy and animal protein over plant protein. Per capita consumption of pulses is not widely measured. The total availability of pulses for food across countries ranges from approximately 2 kg per capita per year in high-income countries to 10–15 kg in middle-income countries, mostly in Asia and Latin America (McDermott and Wyatt, 2017). The growth rate in productivity for almost all the pulses (except beans and chickpeas) has been very low. In cowpeas and pigeon peas, the growth rate has been negative in the current decade (Table 9.2).

Table 9.2

| Year | Beans Dry | Chickpea | Cowpea | Lentils | Peas Dry | Pigeon Pea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth in Area of Pulses Since 1981–2014 | ||||||

| 1981–1990 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 5.40 | 4.08 | 2.21 | 2.59 |

| 1991–2000 | − 0.96 | 1.03 | 2.78 | 1.37 | − 3.14 | 0.14 |

| 2001–2010 | 1.15 | 2.32 | 2.25 | 0.19 | 0.55 | 0.90 |

| 2011–2014 | − 0.19 | 1.67 | 6.24 | 2.87 | 1.22 | 6.33 |

| Growth in Production of Pulses Since 1981–2014 | ||||||

| 1981–1990 | 1.08 | 1.13 | 6.69 | 6.07 | 7.91 | 3.1 |

| 1991–2000 | 0.58 | 2.47 | 4.49 | 1.77 | − 2.48 | 1.57 |

| 2001–2010 | 2.19 | 4.41 | 5.71 | 2.94 | − 0.14 | 3.34 |

| 2011–2014 | 4.28 | 6.26 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 2.64 | 3.63 |

| Growth in Yield of Pulses Since 1981–2014 | ||||||

| 1981–1990 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 1.23 | 1.91 | 5.58 | 0.50 |

| 1991–2000 | 1.56 | 1.42 | 1.67 | 0.40 | 0.68 | 1.43 |

| 2001–2010 | 1.03 | 2.04 | 3.38 | 2.74 | − 0.69 | 2.42 |

| 2011–2014 | 4.48 | 4.51 | − 1.26 | 0.90 | 1.40 | − 2.54 |

Source: FAO, 2016. Food Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets. FAO, p. 139.

There are multiple reasons for stagnating pulse production. Pulses are cultivated in unirrigated areas, to a great extent, on what is generally poor quality acreage. There has been no major technological breakthrough yet which produced high-yielding varieties of pulses. The few available improved varieties not widely adaptable, and they disease-prone. Certified seeds can be difficult to obtain, and when it is an option, farmers with access to irrigation prefer to plant more lucrative crops (Sathe and Agarwal, 2004). The lack of an assured market is another factor in pulses’ poor performance. Compared to the market for cereals in many parts of the country, the markets for pulses are thin and fragmented (Reddy, 2004).

Pulses have a volatile market. There has been a spur in the demand for pulses in the developing countries due to income growth. To meet this demand, some developed countries have increased their pulse production to exploit this burgeoning market. India remains both the highest producer and consumer of pulses. Some of the major pulse-importing countries are India, Pakistan, China, Egypt, the United States, Turkey, and Italy. The major pulse-exporting countries are Canada, Australia, the United States, China, the Russian Federation, and Argentina.

9.3 Lentils: An Overview

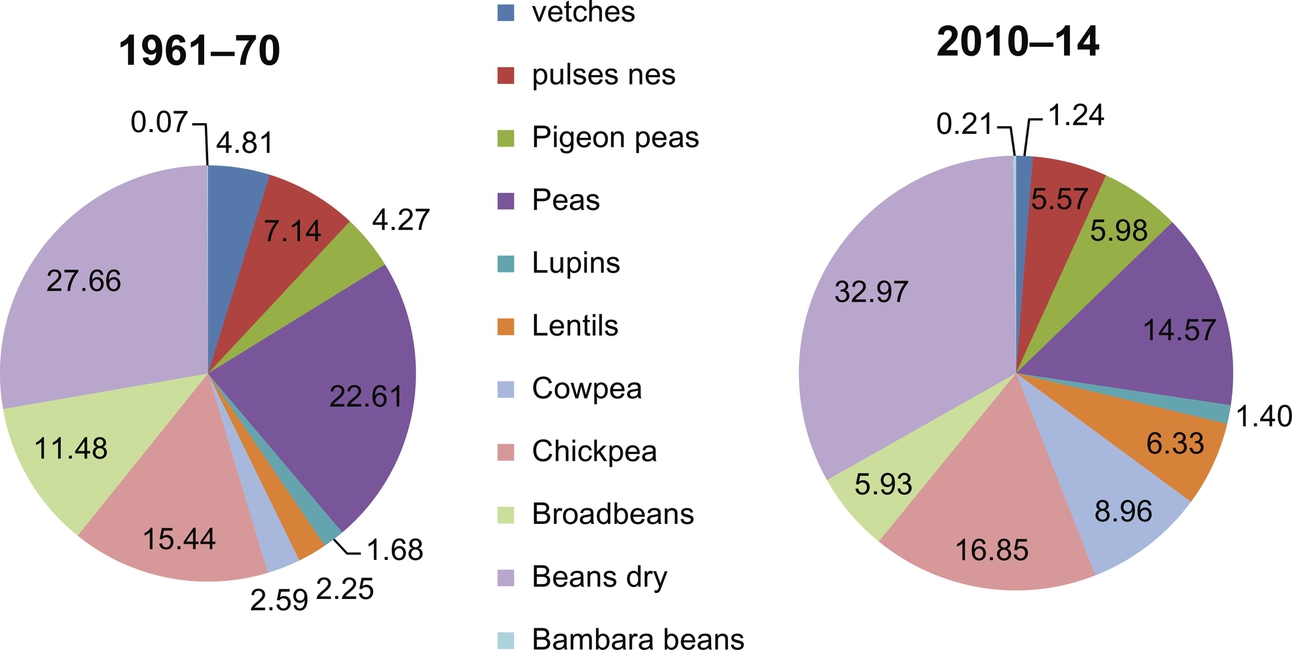

As a percentage of the total number of pulses, peas, broad beans, vetches, and pulses have decreased from the 1960s to the present decade, whereas cowpeas, dry beans, pigeon peas, and lentils have increased their proportion in the overall total. The share of lentils, in particular, has increased from 2.25% of the total in the 1960s to 6.33% in the current decade. Lentils were one of the first domesticated plant species; they are as old as einkorn, emmer, barley, and peas (Harlan, 1992). Lentil seeds come in a range of sizes and colors. They are lens-shaped (the word “lentil” is derived from the Latin word “lens”), generally from 2 to 9 mm in diameter, and vary from 15,600 to 100,000 seeds per pound (Sell, 1993). Though small in size, lentils are gaining importance in human diet due to their ease of preparation and high nutritional value. Lentils are the richest source of dietary protein among plants that are consumed without industrial processing (Sharma, 2009). Lentils are also a very good source of cholesterol-lowering fiber and are beneficial in managing blood-sugar-related disorders. Lentils are a good source of micronutrients like molybdenum, folate, copper, phosphorus, manganese, and iron. Usually, lentils are grown in the subtropics with winter rainfall, in warm temperate regions, and in the tropics and subtropics with summer rainfall, either during cool dry seasons or at high altitudes (Al-Issa, 2006) (Fig. 9.2).

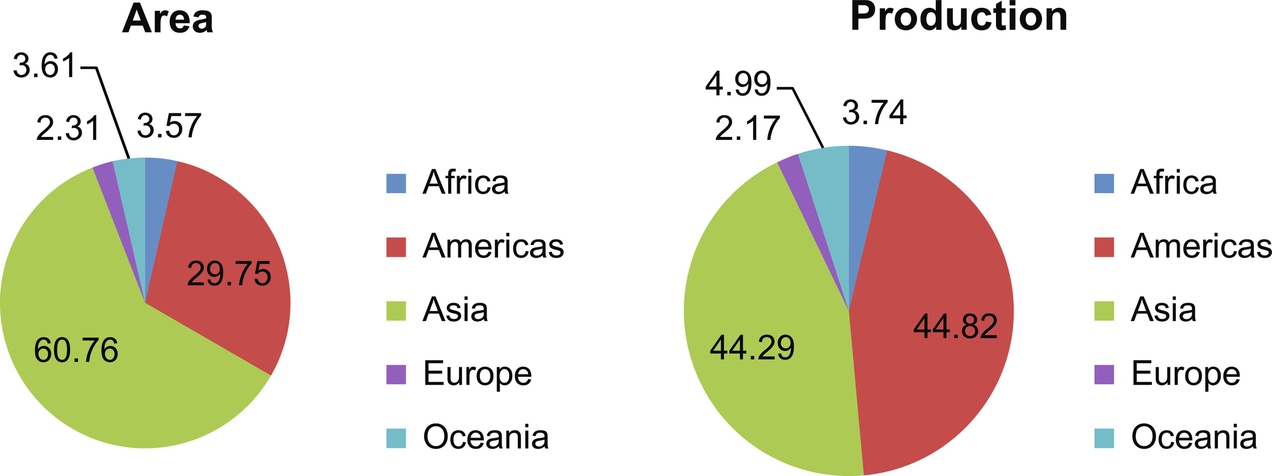

Asia and the Americas contribute around 90% of the world’s lentil-sown area and lentil production. In the Americas, lentils are mainly grown in Canada and the United States. India is the largest producer of lentils in Asia. Other lentil-producing countries include Turkey, Nepal, China, Bangladesh, Syria, and Iran. While around 61% of the world’s area sown in lentils is in Asia, it produces only 44% of the world’s lentil harvest. The Americas, on the other hand, have only around 30% of the world’s lentil-sown area, contributing to around 45% of the world’s lentil production. This shows wide variation in lentil yields between the developed and developing worlds. The average lentil yield in the Americas (1607 kg/ha) is more than double the average yield in Asia (778 kg/ha), which is the main reason for Asia’s smaller share of world production (Fig. 9.3).

On average, about 70% of all the world’s lentil production is consumed in the countries where they are produced (Singh and Singh, 2014). The major exporters of lentils are Canada, Turkey, Australia, and the United States, and the leading importers are India, Pakistan, China, Egypt, the United States, Turkey, Italy, Algeria, the UK, and Sri Lanka.

9.4 Indian Pulse Scenario

Pulses occupy an important and unique place in the Indian food basket. Pulses are particularly important given that the largest number of malnourished people in the world live in India. A large percentage of Indians suffer from nutrition problems including protein deficiency (Roy et al., 2016). Not only is India the largest producer and consumer of pulses, it is also one of the highest pulse-importing countries. Pulses in India are grown on marginal lands under rain-fed conditions with very low input levels, resulting in low productivity. In 2015–16, India produced around 16.35 million tons of pulses. Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Jharkhand, and Bihar are the major pulse producing states in India.

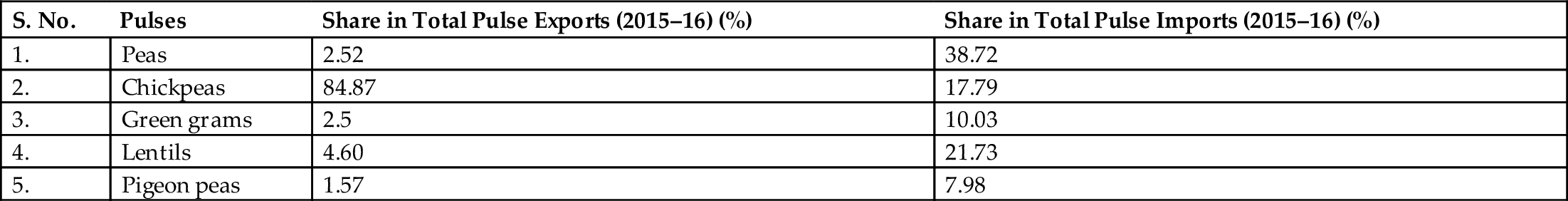

Because pulses are the major protein source for the large vegetarian population of the country, production is always short of demand. India has to import pulses to meet the demand for domestic consumption. In the year 2015–16, India imported 5.79 million tons of pulses. Due to high demand for pulses for consumption, not much is left for export, and Indian pulse exports in the year 2015–16 were merely 0.25 million tons, leaving 21.89 million tons of pulses for domestic consumption (Table 9.3).

Table 9.3

| S. No. | Pulses | Share in Total Pulse Exports (2015–16) (%) | Share in Total Pulse Imports (2015–16) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Peas | 2.52 | 38.72 |

| 2. | Chickpeas | 84.87 | 17.79 |

| 3. | Green grams | 2.5 | 10.03 |

| 4. | Lentils | 4.60 | 21.73 |

| 5. | Pigeon peas | 1.57 | 7.98 |

Source: Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmer’s Welfare, 2015–16.

Gram, pigeon peas, black grams, and green grams, constitute more than 70% of the pulses produced in India. Chickpeas constitute the single largest share of India’s pulse exports, amounting to 84.87% of the total pulse exports during 2015–16, mainly due to the kabuli type. On the import side, peas are the most important pulses, amounting to 38.72% of the total pulse imports, followed by lentils, which contribute 21.73% of India’s total pulse imports.

9.4.1 Trade Policy on Pulses

The Advance Authorization Scheme (AAS) allows import of pulses for export after domestic processing and value addition. Due to the upsurge in pulse prices, the Central Government prohibited the export of pulses in 2006. With the country’s pulse production reaching a record high of 22.4 million tons in 2016–17 (compared to 16.3 million tons in the previous year), in September 2017, the government lifted the ban on the export of chickpea, black gram, and green gram to help farmers earn remunerative prices.

Kabuli chana, organic pulses, and lentils are allowed for export in limited quantities, provided the export contracts are registered with Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA), exports are made through customs electronic data interchange (EDI) ports, and APEDA certifies the produce as organic. Since June 2014, exports to Bhutan have been exempted from any ban without any quantitative restrictions. The export of pulses has been permitted in restricted quantities to the Republic of Maldives from 2014 to 15 to 2016–17. By contrast, the import of pulses is free of any quantitative restrictions.

On the import front, the government had reduced the allowable stock limit of pulses to 350 metric tons in October 2015, which was later reversed in November 2015. Now, import of pulses is free without any quantitative restrictions. The bound, statutory, and applied duties on some of the important pulses are given in the Table 9.4.

9.4.2 SWOT Analysis of Domestic Production Vis-à-Vis Import of Pulses

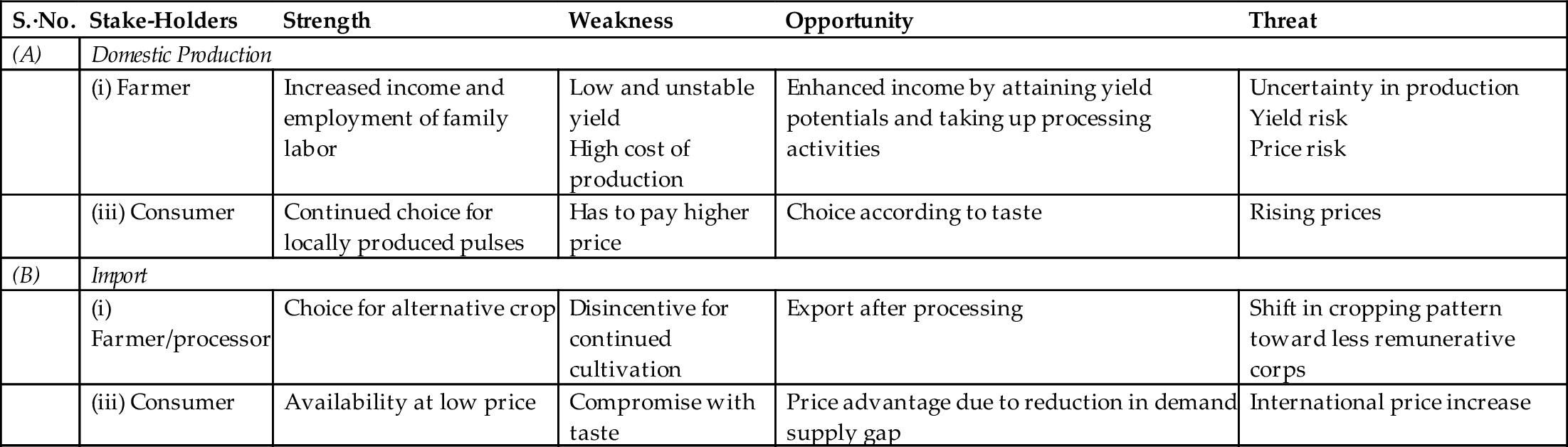

The demand for pulses in the country can be met through either domestic production, import, or a combination of both. The extent to which domestic production and import are combined has varied implications for the stakeholders like producer farmer, processor, and consumer. The SWOT analysis of domestic production vis-à-vis imports in the context of different stakeholders like producer farmer, processor, and consumer in the context of India is summarized in Table 9.5.

Table 9.5

| S.·No. | Stake-Holders | Strength | Weakness | Opportunity | Threat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | Domestic Production | ||||

| (i) Farmer | Increased income and employment of family labor | Low and unstable yield High cost of production | Enhanced income by attaining yield potentials and taking up processing activities | Uncertainty in production Yield risk Price risk | |

| (iii) Consumer | Continued choice for locally produced pulses | Has to pay higher price | Choice according to taste | Rising prices | |

| (B) | Import | ||||

| (i) Farmer/processor | Choice for alternative crop | Disincentive for continued cultivation | Export after processing | Shift in cropping pattern toward less remunerative corps | |

| (iii) Consumer | Availability at low price | Compromise with taste | Price advantage due to reduction in demand supply gap | International price increase | |

9.4.3 The Dal Shock of 2015–16

Due to a sharp rise in pulse prices in the earlier part of 2016, bullish expectations prompted Indian traders enter into forward contracts which were speculative in nature and made without any knowledge about the crop prospects in India and abroad. After July 2016, the pulse market across the world underwent a dramatic change, with countries including India planting record acreages. This, coupled with a well-distributed southwest monsoon, resulted in a record harvest. The domestic and international pulse prices of pulses plummeted. Following this, there were several contract defaults and forced price negotiations, sending the wrong signals about India to the world pulse market.

9.5 Lentil Production in India

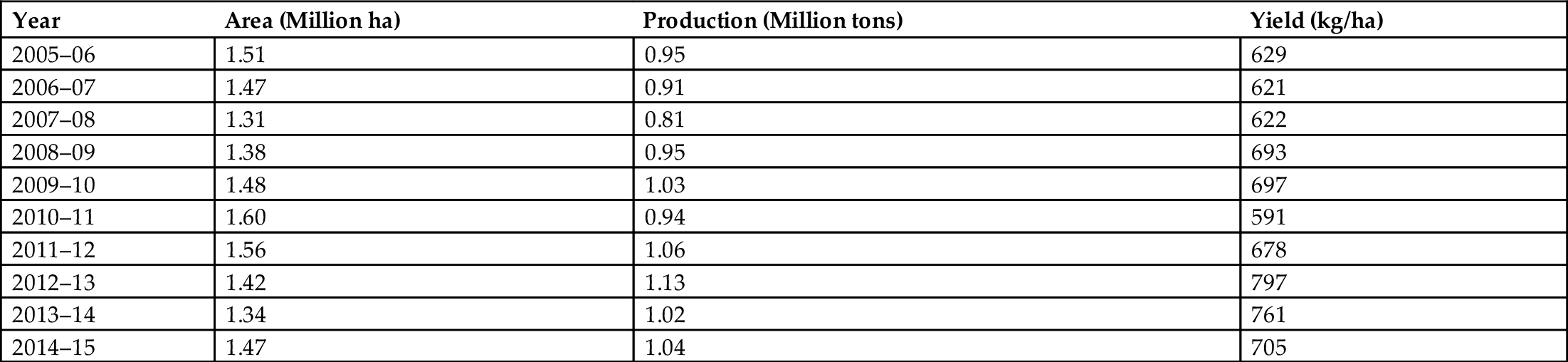

Lentils are grown as a rabi (winter season) crop in India. India ranks first in terms of area and second in production for lentils in the world. Canada ranks first in production of lentils because of the high productivity of 1632 kg/ha. Canada, India, Turkey, Australia, Nepal, and Bangladesh are the lentil major producers. In India, lentils are produced in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Rajasthan, and Assam. States like Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar contribute more than 80% of India’s lentil production. The temporal pattern of growth in area, production, and yield of lentils in India is given in Table 9.6.

Table 9.6

| Year | Area (Million ha) | Production (Million tons) | Yield (kg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–06 | 1.51 | 0.95 | 629 |

| 2006–07 | 1.47 | 0.91 | 621 |

| 2007–08 | 1.31 | 0.81 | 622 |

| 2008–09 | 1.38 | 0.95 | 693 |

| 2009–10 | 1.48 | 1.03 | 697 |

| 2010–11 | 1.60 | 0.94 | 591 |

| 2011–12 | 1.56 | 1.06 | 678 |

| 2012–13 | 1.42 | 1.13 | 797 |

| 2013–14 | 1.34 | 1.02 | 761 |

| 2014–15 | 1.47 | 1.04 | 705 |

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, 2016. Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India, New Delhi.

9.5.1 Economic Classification

Based on the seed size and test weight, lentils are classified into two main groups:

- (i) Bold-seeded: Includes sub sp. macrosperma, with the test weight of more than 25 g. Also known locally as Masuror MalkaMasur, and mainly cultivated in Bundelkhand region of UP/MP and Maharashtra state.

- (ii) Small-seeded: Sub sp. microsperma, test weight less than 25 g, locally known as masuri, and primarily grown in the Indo-Gangetic plains of NEPZ (UP, Bihar, West Bengal, and Assam) (Tiwari and Shivhare, 2016).

9.5.2 The Lentil Trade Scenario

Due to the mismatch between supply and demand for pulses, the prices of pulse crops have increased exorbitantly. To meet the demand for pulses, India has been importing a large quantity of them in recent years (Reddy and Reddy, 2010). During 2015–16, out of the total 5,797,000,000 tons of pulses imported by India, almost 39% were peas, 22% were lentils, 18% chickpeas, 10% green and black gram, and 8% were pigeon peas. Lentils are the second most imported pulses in India, second only to peas. India imports lentils from Canada, the United States, Australia, Turkey, and Mozambique.

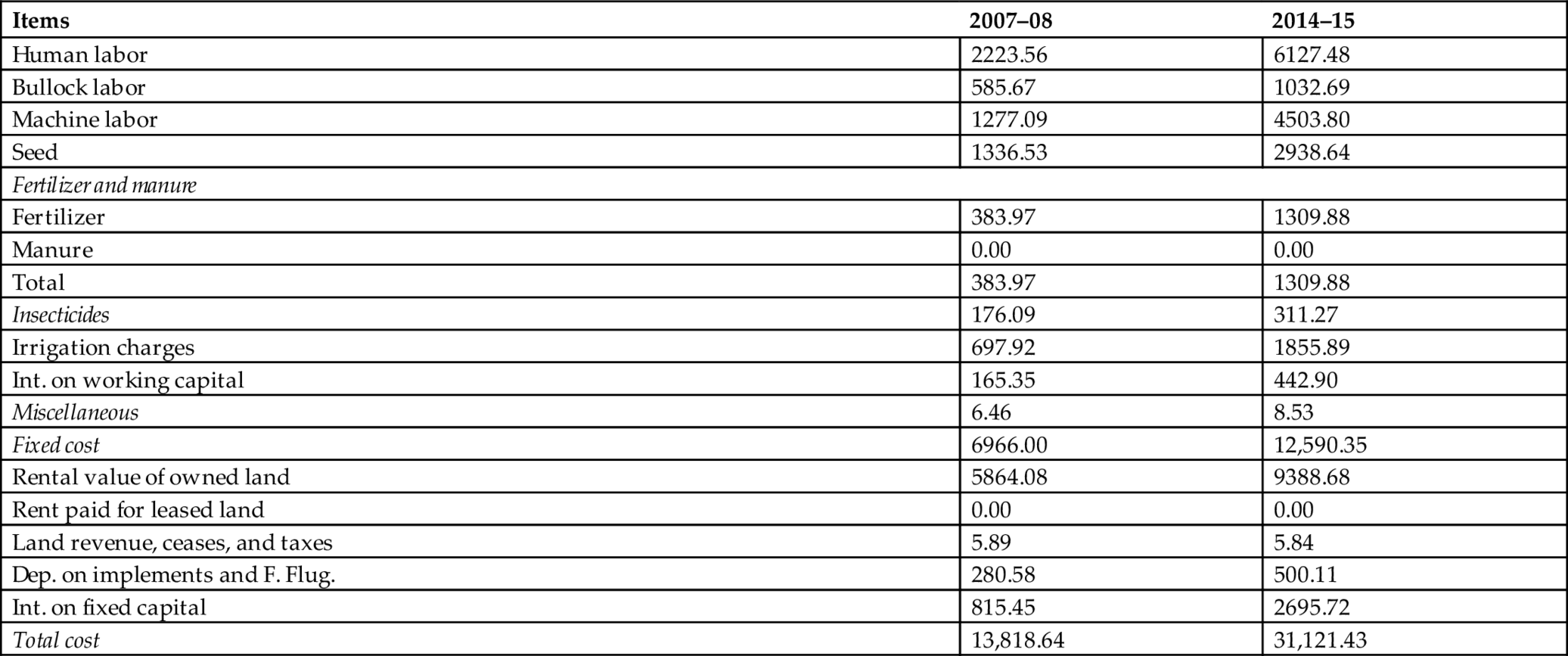

9.6 Comparative Economics of Cost of Production of Lentils in Madhya Pradesh

The details of cost of cultivation for lentils for the years 2007–08 and 2014–15 are given in Table 9.7.

Table 9.7

| Items | 2007–08 | 2014–15 |

|---|---|---|

| Human labor | 2223.56 | 6127.48 |

| Bullock labor | 585.67 | 1032.69 |

| Machine labor | 1277.09 | 4503.80 |

| Seed | 1336.53 | 2938.64 |

| Fertilizer and manure | ||

| Fertilizer | 383.97 | 1309.88 |

| Manure | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 383.97 | 1309.88 |

| Insecticides | 176.09 | 311.27 |

| Irrigation charges | 697.92 | 1855.89 |

| Int. on working capital | 165.35 | 442.90 |

| Miscellaneous | 6.46 | 8.53 |

| Fixed cost | 6966.00 | 12,590.35 |

| Rental value of owned land | 5864.08 | 9388.68 |

| Rent paid for leased land | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Land revenue, ceases, and taxes | 5.89 | 5.84 |

| Dep. on implements and F. Flug. | 280.58 | 500.11 |

| Int. on fixed capital | 815.45 | 2695.72 |

| Total cost | 13,818.64 | 31,121.43 |

Source: CACP Reports by Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare and GoI, New Delhi (2011 and 2016).

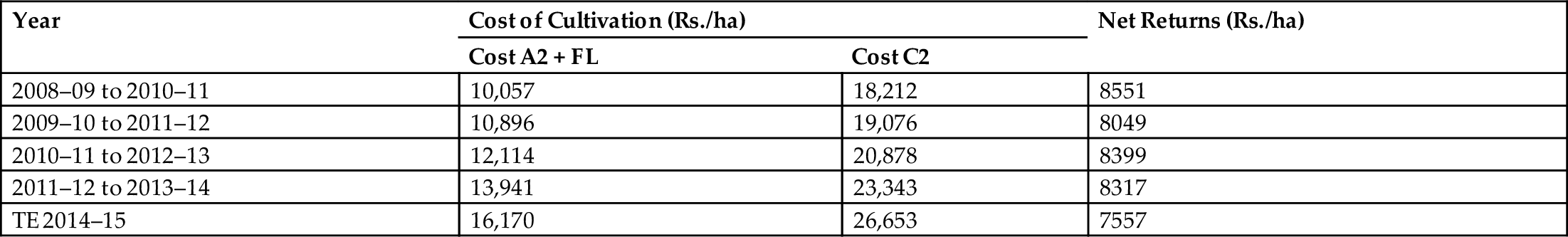

During the period 2007–08 and 2014–15, the operational cost for lentil cultivation has increased by around 170%, and the fixed cost has increased by around 80%. Consequently, the total cost of cultivation has increased by 125%. This increase in variable cost has been mainly due to increasing costs for machine labor, fertilizers, human labor, and seeds. The costs of the first two have increased by more than 200%, and the latter two, by more than 100%. The increase in machine labor could be a result of a hike in diesel prices during the period. Similarly, the irrigation charges have gone up by about 165% during this period, which again is largely due to an increase in electricity charges and diesel prices. The total cost of cultivation has increased by around 125% during this period (Table 9.8).

Table 9.8

| Year | Cost of Cultivation (Rs./ha) | Net Returns (Rs./ha) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost A2 + FL | Cost C2 | ||

| 2008–09 to 2010–11 | 10,057 | 18,212 | 8551 |

| 2009–10 to 2011–12 | 10,896 | 19,076 | 8049 |

| 2010–11 to 2012–13 | 12,114 | 20,878 | 8399 |

| 2011–12 to 2013–14 | 13,941 | 23,343 | 8317 |

| TE 2014–15 | 16,170 | 26,653 | 7557 |

Source: Commission of Agricultural Cost and Prices, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, 2016.

The data in the above table makes it clear that the cost of cultivating lentils has increased over the years from 2008 to 09 to 2014–15. While the sum of cost A2 and family labor have increased by around 60% during this period, the cost C2 has increased by 46%. The net returns, on the other hand, have decreased over the years. From 2008 to 09 to 2014–15, net returns decreased by around 11%. The main reasons for this decrease might be one or two bad agricultural years. In spite of the surge in pulse prices over the years, it is worth pointing out that the domestic prices of lentils have not been commensurate with the increase in cost of cultivation during this period.

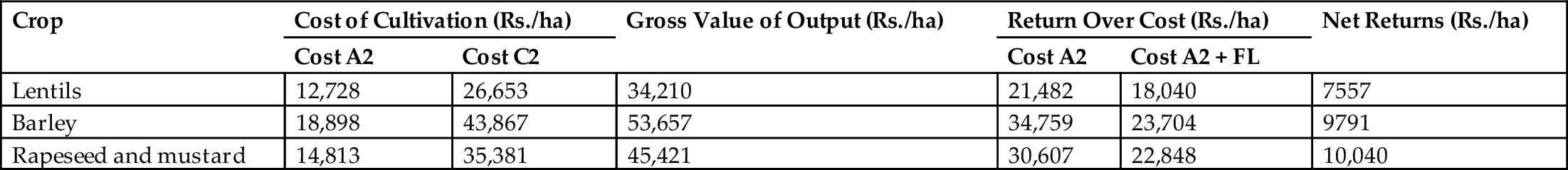

9.7 Comparative Economics of Lentils and Competing Crops

The comparative economics of lentils and their competing crops in terms of cost of cultivation, gross return, and profit margin on unit area basis in India are given in Table 9.9.

Table 9.9

| Crop | Cost of Cultivation (Rs./ha) | Gross Value of Output (Rs./ha) | Return Over Cost (Rs./ha) | Net Returns (Rs./ha) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost A2 | Cost C2 | Cost A2 | Cost A2 + FL | |||

| Lentils | 12,728 | 26,653 | 34,210 | 21,482 | 18,040 | 7557 |

| Barley | 18,898 | 43,867 | 53,657 | 34,759 | 23,704 | 9791 |

| Rapeseed and mustard | 14,813 | 35,381 | 45,421 | 30,607 | 22,848 | 10,040 |

Source: Commission of Agricultural Cost and Prices, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, 2016.

Pulses in India are grown as subsistence crops on minimum or no irrigation. This is why rabi crops such as wheat that are cultivated on irrigated land with assured irrigation have not been considered competing crops for lentils. But the water requirements of rapeseed, mustard, and barley are much lower than that of wheat, so those crops could be considered to compete with lentils for area. The returns over cost of cultivation are highest for rapeseed and mustard, followed by barley. Lentils, with a net return of Rs. 7557/ha, have the lowest returns over cost. These low returns over cost are the biggest impediment to lentil cultivation in India, whereas crops like barley, which were not in demand few years ago, have gained momentum because of an assured market (mainly the malt industry, in the case of barley).

9.7.1 Prices of Lentils in India

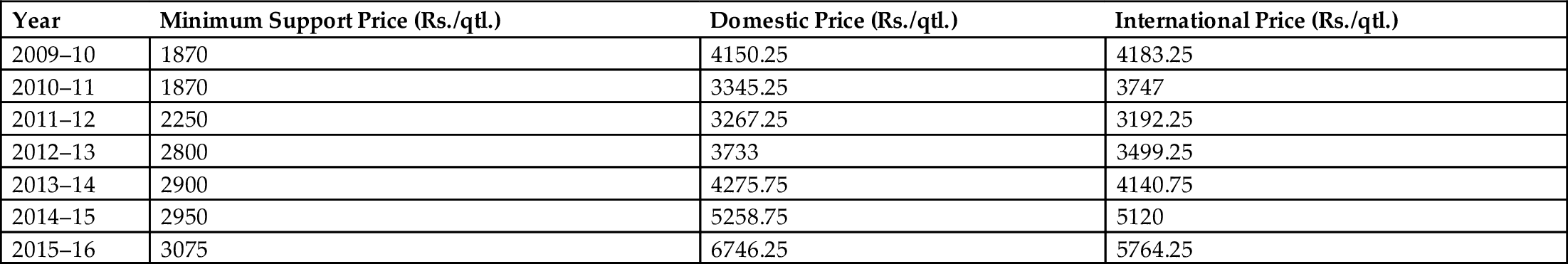

It is evident from the table that the domestic price of lentils has increased at a faster rate than the MSP. A comparison of domestic prices with international prices shows that during 2009–10 and 2010–11, domestic prices were lower. However, from 2011 to 12 onward, domestic prices have been higher than international prices. This clearly shows that, at existing costs and returns for domestically grown lentils, India lacks a comparative advantage in lentil cultivation; this is the reason India is a net importer of lentils. Lentils’ cost of cultivation has increased considerably over the years. However, due to the lack of a major technological breakthrough resulting in new high-yielding and drought-resistant varieties, the net returns from lentil cultivation have remained very low. These cost and return scenarios do not favor an acreage increase for lentils. And the major reason is the sensitivity of this crop, as it cannot withstand high wind, rain, or the attack of major diseases (like Stemphylium blight during blossom) compared to other competing crops, which are hardier (Table 9.10).

Table 9.10

| Year | Minimum Support Price (Rs./qtl.) | Domestic Price (Rs./qtl.) | International Price (Rs./qtl.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009–10 | 1870 | 4150.25 | 4183.25 |

| 2010–11 | 1870 | 3345.25 | 3747 |

| 2011–12 | 2250 | 3267.25 | 3192.25 |

| 2012–13 | 2800 | 3733 | 3499.25 |

| 2013–14 | 2900 | 4275.75 | 4140.75 |

| 2014–15 | 2950 | 5258.75 | 5120 |

| 2015–16 | 3075 | 6746.25 | 5764.25 |

Source: Commission of Agricultural Cost and Prices, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, 2016.

9.7.2 Opportunities in Rice Fallows

Rice-wheat is the major crop rotation pattern for food self-security in India. Rice cultivated all over the country occupies an area of about 44 million hectares (Agricultural Statistics, 2014) and is grown under both irrigated and rain-fed conditions in various cropping systems. In irrigated areas, rice-wheat, rice-rice, rice-sugar cane, rice-ground nut, rice-vegetables, and rice-mustard are important crop rotations, whereas, in rain-fed areas, rice-pulses, rice-sunflower, rice-sesame, and rice-fallow are prevalent. Eastern India, the rice-dominated area of the country, accounts for about 63.3% of India’s total rice area. About 78.8% of rice area in the region is rain-fed, with the result that rice is grown only during the rainy season (June-September), after which, the land lies fallow, hence the name, “rice fallow.”

The existing rice fallow, an area of 11.65 million ha (Subbarao et al., 2001; NAAS, 2013) after the rice harvest is almost equivalent to the net sown area of Punjab, Haryana, and Western Uttar Pradesh — the sheet of green revolution in India. Of the total rice fallow area, about 82% lies in the eastern region (Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and West Bengal). If this area is brought under cultivation, it may usher in another green revolution in the country, benefiting millions of poor, deprived, small landholders (Joshi et al., 2002; Agricultural Statistics, 2011). The introduction of short-duration pulses like lentils, grass peas, and chickpeas, (which should fit the cropping sequence) will not only provide nutritional security, improve soil health, and increase cropping intensity, but also will increase income. Interventions by the ICAR and CGIAR institutes revealed that lentil varieties like HUL-57, Malika, and Subrata performed well, yielding up to 1.1 t/ha in rice fallows. With proper technology targeting and upscaling, there are about 1–2 million ha in rice fallows areas which could be potentially planted in lentils. This will not only help increase lentil area and production in India, but will also provide an extra source of income for farmers.

9.8 Conclusions

India ranks first in area, second in production, and lags behind several countries in lentil productivity. In India, lentils are mainly produced in the BIMARU (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh) states as a rain-fed crop. India is a net importer of pulses, and lentils are the second most-imported pulse, second only to peas. Over the past decade, lentils’ production cost has more than doubled. The net returns for lentils have shown a declining trend, as there has been no substantial breakthrough in yield-enhancing varieties. Increasing cost of cultivation, coupled with low yields, renders this crop less profitable than other competing rabi crops. Additionally, lentils’ low Minimum Support Price, compared to domestic and international prices, discourages area increase. Higher domestic prices, as compared to international prices, encourage more imports. These price dynamics are not favorable when it comes to enhancing domestic lentil production. Enhancing domestic lentil production requires a two-pronged approach: enable research favoring development of high yielding draught resistant varieties, and set price policy to favor acreage increase.