SĀDHANA PĀDA

Tapaḥ-svādhyāyeśvara-praṇidhānāni kriyā-yogaḥ.

asceticism; austerity

asceticism; austerity  self-study; study which leads to the knowledge of the Self through Japa

self-study; study which leads to the knowledge of the Self through Japa  (and) self-surrender, or resignation to God

(and) self-surrender, or resignation to God  preliminary (practical) Yoga.

preliminary (practical) Yoga.

1. Austerity, self-study and resignation to Iśvara constitute preliminary Yoga.

The last three of the five elements of Niyama enumerated in II-32 have been placed in the above Sūtra under the title of Kriyā-Yoga. This is rather an unusual procedure and we should try to grasp the significance of this repetition in a book which attempts to condense knowledge to the utmost limit. Obviously, the reason why Tapas, Svādhyāya and Iśvara-praṇidhāna are mentioned in two different contexts lies in the fact that they serve two different purposes. And since the development of the subject of self-culture in Section II of the Yoga-Sūtras is progressive in character it follows that the purpose of these three elements in II-1 is of a more preliminary nature than that in II-32. Their purpose in 11-32 is the same as that of the other elements of Niyama and has been discussed at the proper place. What is the purpose in the context of II-1? Let us see.

Anyone who is familiar with the goal of Yogic life and the kind of effort it involves for its attainment will realize that it is neither possible nor advisable for anybody who is absorbed in the life of the world and completely under the influence of Kleśas to plunge all at once into the regular practice of Yoga. If he is sufficiently interested in the Yogic philosophy and wants to enter the path which leads to its goal he should first accustom himself to discipline, should acquire the necessary knowledge of the Dharma-Śāstras and especially of the Yoga-Śāstras and should reduce the intensity of his egoism and all the other Kleśas which are derived from it. The difference between the outlook and the life of the ordinary worldly man and the life which the Yogi is required to live is so great that a sudden change from the one to the other is hot possible and if attempted may produce a violent reaction in the mind of the aspirant, throwing him back with still greater force into the life of the world. A preparatory period of self-training in which he gradually assimilates the Yogic philosophy and its technique and accustoms himself to self-discipline makes the transition from the one life to the other easier and safer. It also incidentally enables the mere student to find out whether he is sufficiently keen to adopt the Yogic life and make a serious attempt to realize the Yogic ideal. There are too many cases of enthusiastic aspirants who for no apparent reason cool off, or finding the Yogic discipline too irksome, give it up. They are not yet ready for the Yogic life.

Even where there is present the required earnestness and the determination to tread the path of Yoga it is necessary to establish a permanent mood and habit of pursuing its ideal. Mere wishing or willing is not enough. All the mental powers and desires of the Sādhaka should be polarized and aligned with the Yogic ideal. Many aspirants have very confused and sometimes totally wrong ideas with regard to the object and technique of Yoga. Many of them have very exaggerated notions with regard to their earnestness and capacity to tread the path of Yoga. Their ideas become clarified and their capacity and earnestness are tested severely in trying to practise Kriyā-Yoga. They either emerge from the preliminary self-discipline with a clearly defined aim and a determination and capacity to pursue it to the end with vigour and single-minded devotion, or they gradually realize that they are not yet ready for the practice of Yoga and decide to tune their aspiration to the lower key of mere intellectual study.

This preparatory self-discipline is triple in its nature corresponding to the triple nature of a human being. Tapas is related to his will, Svādhyāya to the intellect and Iśvara-praṇidhāna to the emotions. This discipline, therefore, tests and develops all the three aspects of his nature and produces an all-round and balanced growth of the individuality which is so essential for the attainment of any high ideal. This point will become clear when we consider the significance of these three elements of Kriyā-Yoga in dealing with II-32.

There exists some confusion with regard to the meaning of the Saṃskṛta word Kriyā, some commentators preferring to translate it as ‘preliminary’ others as ‘practical’. As a matter of fact Kriyā-Yoga is both practical and preliminary. It is preliminary because it has to be taken up in the initial stages of the practice of Yoga and it is practical because it puts to a practical test the aspirations and earnestness of the Sādhaka and develops in him the capacity to begin the practice of Yoga as distinguished from its mere theoretical study however deep this might be.

Samādhi-bhāvanārthaḥ kleśa-tanūkara-ṇārthaś ca.

trance

trance  for bringing about

for bringing about  afflictions

afflictions

for reducing; for making attenuated

for reducing; for making attenuated  and.

and.

2. (Kriyā-Yoga) is practised for attenuating Kleśas and bringing about Samādhi.

Although the practice of the three elements of Kriyā-Yoga is supposed to subserve the preparatory training of the aspirant it should not therefore be assumed that they are of secondary importance and have only a limited use in the life of the Sādhaka. How effective this training is and to what exalted stage of development it is capable of leading the aspirant will be seen from the second Sūtra which we are considering and which gives the results of practising Kriyā-Yoga. Kriyā-Yoga not only attenuates the Kleśas and thus lays the foundation of the Yogic life but it also leads the aspirant to Samādhi, the essential and final technique of Yoga. It is, therefore, also capable of building to a great extent the superstructure of the Yogic life. The importance of Kriyā-Yoga and the high stage of development to which it can lead the Sādhaka will be clear when we have considered the ultimate results of practising Tapas, Svādhyāya and Iśvara-praṇidhāna in II-43-45.

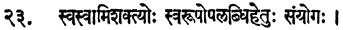

The ultimate stage of Samādhi is, of course, reached through the practice of Iśvara-praṇidhāna as indicated in I-23 and II-45. Although the two results of practising Kriyā-Yoga enumerated in II-2 are related to the initial and ultimate stages of Yogic practice they are really very closely connected and in a sense complementary. The more the Kleśas are attenuated the greater becomes the capacity of the Sādhaka to practise Samādhi and the nearer he draws to his goal of Kaivalya. When the Kleśas have been reduced to the vanishing point he is in habitual Samādhi (Sahaja-Samādhi), at the threshold of Kaivalya.

We shall take up the discussion of these three elements of Kriyā-Yoga as part of Niyama in II-32.

Avidyāsmitā-rāga-dveṣābhiniveśāḥ kleśāḥ.

ignorance; lack of awareness; illusion

ignorance; lack of awareness; illusion  ‘I-amness’ egoism;

‘I-amness’ egoism;  attraction; liking

attraction; liking  repulsion; dislike

repulsion; dislike

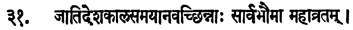

(and) clinging (to life); fear of death

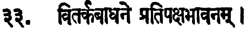

(and) clinging (to life); fear of death  pains; afflictions; miseries; causes of pain.

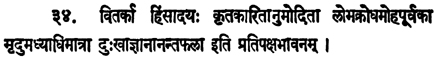

pains; afflictions; miseries; causes of pain.

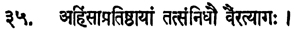

3. The lack of awareness of Reality, the sense of egoism or ‘I-am-ness’ attractions and repulsions towards objects and the strong desire for life are the great afflictions or causes of all miseries in life.

The philosophy of Kleśas is really the foundation of the system of Yoga outlined by Patañjali. It is necessary to understand this philosophy thoroughly because it provides a satisfactory answer to the initial and pertinent question, ‘Why should we practise Yoga?’ The philosophy of Kleśas is not peculiar to this system of Yoga. In its essential ideas it forms the substratum of all schools of Yoga in India though perhaps it has not been expounded as clearly and systematically as in the Sāṃkhya and Yoga Darśanas.

Many Western scholars have not fully understood the real significance of the philosophy of Kleśas and tend to regard it merely as an expression of the pessimism which they think characterizes Hindu philosophical thought. At best they take it in the light of an ingenious philosophical conception which provides the necessary foundation for certain systems of philosophy. That it is related to the hard facts of existence and is based upon a close and scientific analysis of the phenomena of human life, they would be hardly prepared to accept.

Purely academic philosophy has always been speculative and the essential task of the expounder of a new philosophical system is considered to be to provide a plausible explanation of the fundamental facts of life and existence. Some of these explanations which form the basis of certain philosophical systems are extraordinarily ingenious expositions and illustrations of reasoned thought, but they are purely speculative and are based on the superficial phenomena of life observed through the senses. Philosophy is considered to be a branch of learning concerned with evolving theories about life and the Universe. Whether these theories are correct and help in solving the real problems of life is not the concern of the philosopher. He has only to see that the theory which he puts forward is intellectually sound and provides an explanation of the observed facts of life with the maximum of plausibility. Its value lies in its rationality and ingeniousness and possibly intellectual brilliance, not in its capacity to provide a means of overcoming the miseries and sufferings incidental to human life. No wonder, academic philosophy is considered barren and futile by the common man and treated with indifference, if not with veiled contempt.

Now, in the East, though many ingenious and purely speculative philosophies have been expounded from time to time, philosophy has been considered, on die whole, as a means of expounding the real and deeper problems of human life and providing clear-cut and effective means for their solution. There is not much demand for purely speculative systems of philosophy and such as exist are treated with a kind of amused tolerance as intellectual curiosities—nothing more. The great problem of human life is too urgent, too serious, too profound, too awful to leave any room for the consideration of mere intellectual theories, however brilliant these might be. If your house is on fire you want a means of escape and are not in a mood to sit down and read a brilliant thesis on architecture at that time. Those who can remain satisfied with purely speculative philosophies have not really understood the great and urgent problem of human life and its deeper significance. If they see this problem as it really is then they can be interested only in such philosophies as offer effective means for its solution.

Although the perception of the inner significance of the real problem of human life is dependent upon an inner change in consciousness and awakening of our spiritual faculties and cannot be brought about by an intellectual process of reasoning imposed from without, still, let us consider man in time and space and see whether his circumstances justify the extraordinary complacency which we find not only among the common people but also among the so-called philosophers.

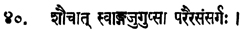

Let us first consider man in space. In giving us a true picture of man in the physical Universe of which he is a part nothing has helped us so much as the discoveries of modern Science. Even before man could use a telescope the vision of the sky at night filled him with awe and wonder at the immensity of the Universe of which he was an insignificant part. But the researches of astronomers have shown that the physical Universe is almost unbelievably larger than what it appears to the naked eye. The 6,000 stars that are within the range of our unaided vision form, according to Science, a group which is only one among at least a billion other groups which stretch out to infinity in every direction. Astronomers have made a rough calculation of the number of stars that are within the range of the high-powered telescopes available these days and think there may be as many as 100 billion stars in our galaxy alone, some smaller than our sun and others very much bigger. This galaxy which is only one of 100,000 already definitely known to astronomers is so vast that light with a speed of 186,000 miles per second takes about 100,000 years to travel from one side to the other. In this vast ‘known’ Universe even our Solar system with its maximum orbital (of planets) diameter of 7 billion miles occupies an insignificant place by comparison. Narrowing down our vision to the Solar system we again find that the earth occupies only an insignificant place in the huge distances that are involved. It has a diameter of 8,000 miles compared with 865,000 miles of the sun and moves slowly in its orbit round the sun at an approximate distance of 93 million miles. Coming down still further to our earth we find man occupying an insignificant position as far as his physical body is considered. A microbe moving over the surface of a big school globe is physically a formidable object in comparison with man moving over the surface of the earth.

This is the awful picture that Science gives of man in the physical Universe, but so great is the illusion of Māyā and the complacence which it engenders that we not only do not wonder about human life and tremble at our destiny but go through life engrossed in our petty pursuits, and sometimes even obsessed with a sense of self-importance. Even the scientists who scan this vast Universe every night with their telescopes remain unaware of the profound significance of what they see.

The picture which Science presents of our physical world in its infinitesimal aspect is no less disconcerting. That physical matter constituting our bodies consisted of atoms and molecules has been known for quite a long time. But the recent researches of Science in this field have led to some startling discoveries. The hard and indestructible atoms which constituted the bed-rock of modem scientific materialism have been found to be nothing more than different permutations and combinations of two fundamental types of positive and negative charged particles—protons and electrons. The protons form the core of the atom with electrons in varying numbers revolving round it in different orbits with tremendous speed, an atom being thus a Solar system in miniature. And what is still more startling, it has been found that these electrons may be nothing but charges of electricity with no material basis because mass and energy become indistinguishable at the high speed at which electrons move in their orbits. In fact, the conversion of matter into energy which has now become an accomplished fact shows that matter may be nothing more than an expression of locked-up energy. This conclusion which really means that matter disappears into energy has been arrived at, by an irony of fate, by the efforts of materialistic science which was responsible for giving a tremendous materialistic bias to our thinking and living. This hard fact means—and let the reader ponder carefully over this problem—that the well-known and so-called real world which we cognize with our sense-organs, a world of forms, colour, sound, etc., is based upon a phantom world containing nothing more than protons and electrons. These facts have become matters of common knowledge but how many of us, even scientists who work on these problems, seem to grasp the significance of these facts. How many are led to ask the question which should so naturally arise in the light of these facts ‘What is man?’ Is there any further proof needed that the mere intellect is blind and is incapable of seeing even the obvious truths of life, much less the Truth of truths?

Leaving the world of space let us glance for a while at the world of time. Here again we are faced with tremendous immensities of a different nature. An infinite succession of changes seems to extend on both sides into the past and the future. Of this endless expanse of time a period of a few thousand years just behind us is all that is reliably known to us while we have only a vague and hazy conception of what lies in the lap of the uncertain future. For aught we know the sun may explode the very next moment and destroy all life in the Solar system before we know what has happened. We are almost certain that millions and millions of years lie behind us but what has happened in those years we cannot know except by inference from what we observe in the visible Universe of stars around us. The past is like a huge tidal wave advancing and devouring everything in its path. Magnificent civilizations on our earth of which only traces are left and even planets and solar systems have disappeared in this tidal wave never to appear again and a similar relentless fate awaits everything from a grain of dust to a Solar system. Time, the instrument of the Great Illusion devours everything. And yet, look at puny man, whose achievements and glories are also to disappear in this void, how he struts about on the world stage clothed with brief authority or glory in the few moments which have been allotted to him. Surely, this awful panorama of ceaseless change which is unfolding before his eyes should make him pause and at least wonder what is all this about. But does it?

The above picture of man in time and space is not at all over-drawn. A man has only to isolate himself for a while from his engrossing environment and ponder over these facts of life to realize the illusory nature of his life and to feel the so-called zest of life melt away. But few of us have the eyes to look at this awful vision, and if by any chance our eyes open accidently for a while, we find the prospect too terrifying and shut them again, and completely oblivious and unaware of the real nature of life continue to live with our joys and sorrows until the flame of life is snuffed out by the hand of Death.

Now, the above picture of man in space and time has been given not with a view to provide entertainment for the intellectually curious, or even food for thought for the thoughtful, but to prepare the ground for the consideration of the philosophy of Kleśas which forms the foundation of the Yogic philosophy. For the philosophy of Yoga is based on the hard realities of life, harder than the realities of Nature given to us by Science. Those who are not aware of these realities, or are aware only superficially in their intellectual aspects can hardly appreciate the goal or the technique of Yoga. They may find Yoga a very interesting subject for study, even fascinating in some of its aspects, but they cannot have the determination to go through the tremendous labour and ordeals which are required to rend asunder the veils of illusion created by Time and Space, and to contact the Reality which is hidden behind these veils.

With this brief introduction let us now turn to consider the philosophy of Kleśas as it is outlined in the Yoga-Sūtras. Let us first take the Saṃskṛta word Kleśa. It means pain, affliction or misery but gradually it came to acquire the meaning of what causes pain, affliction or misery. The philosophy of Kleśas is thus an analysis of the underlying and fundamental cause of human misery and suffering and the way in which this cause can be removed effectively. This analysis is not based upon a consideration of the superficial facts of life as observed through the senses. The Ṛṣis who expounded this philosophy were great Adepts who combined in themselves the qualifications of a religious teacher, scientist and philosopher. With this triple qualification and synthetic vision they attacked the great problem of life, determined to find a solution of the riddle which Time and Space have created for the illusion-bound man. They observed the phenomena of life not only with the help of their senses and the mind, but in the full conviction that the solution lay beyond even the intellect they dived deeper and deeper into their own consciousness, tearing aside veil after veil, until they discovered the ultimate cause of the Great Illusion and the misery and suffering which are its inevitable results. They discovered, incidentally, in their search other subtler worlds of entrancing beauty hidden beneath the visible physical world. They discovered new faculties and powers within themselves—faculties and powers which could be utilized for studying these subtler worlds and pursuing their enquiry into still deeper layers of their own consciousness. But they did not allow themselves to be entangled by these subtler worlds and did not rest content until they had penetrated deep enough within their consciousness to find an effective and permanent solution of the great problem of life. They discovered in this way not only the ultimate cause of human misery and suffering but also the only effective means of destroying these afflictions permanently.

It is very necessary for the student to realize the experimental nature of this philosophy of Kleśas and the greater philosophy of Yoga of which it is an integral part. These are not the results of speculation or reasoned thought as many systems of philosophy are. The philosophy of Yoga claims to be derived from the results of scientific experiments, guided by the spirit of philosophic enquiry, inspired by religious devotion. We cannot, obviously, verify this essentially scientific system by the ordinary methods of Science and say to the sceptic: ‘Come I will prove it before your eyes.’ We cannot judge it by the ordinary academic standards of philosophers who apply purely intellectual criteria for judging these things. The only way in which it can be verified is to follow the path which was taken by the original discoverers and which is outlined in this system of Yoga. The sceptic might feel that it is unfair to ask him to assume the validity of what he wants to get proved, but this, from the very nature of things, cannot be helped. Those who have seen the fundamental problem of life in its true aspects will consider the gamble worth taking, for that provides the only way out of the Great Illusion. For others it does not matter whether they do or do not believe in the teachings of Yoga. They are not yet ready for the Divine Adventure.

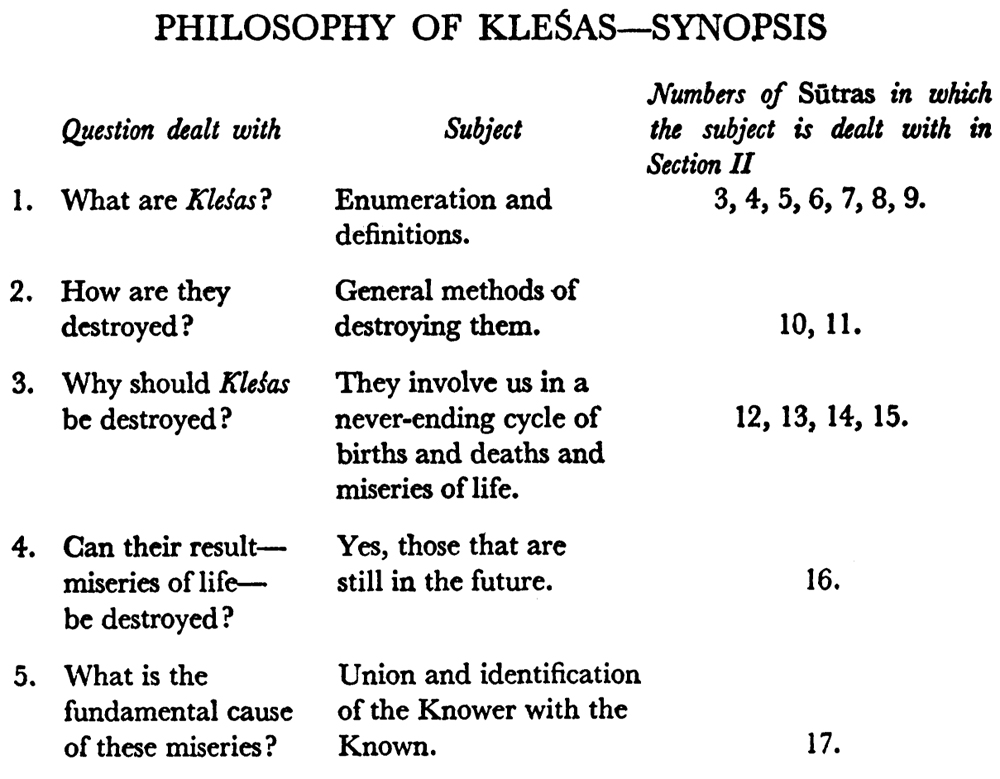

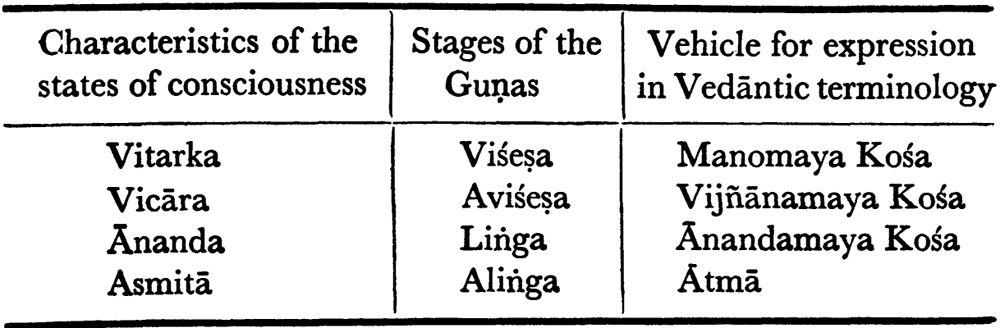

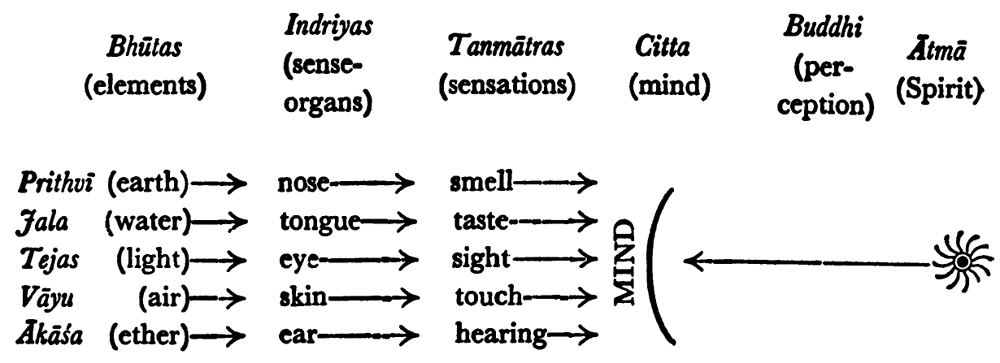

Before discussing in detail the philosophy of Kleśas as outlined in Section II of the Yoga-Sūtras it will be desirable to give an analysis of the whole subject in the form of a table. This will show at a glance the different aspects of the subject and their relation to one another. It will be seen from the summary given in this table—a fact which is difficult to grasp otherwise—that the whole subject has been dealt with in a systematic and masterly manner. The student who wants to get a clear insight into the philosophy of Kleśas will do well, therefore, to go through the following summary carefully and ponder over it before taking up the detailed study of the subject.

The author opens the subject with an enumeration of the five Kleśas in II-3. The English equivalents of the Saṃskṛta words do not correctly and fully convey the ideas implied and the English words which come nearest to the Saṃkṛta names of the Kleśas have been given. The underlying significance of the five Kleśas will be explained in dealing with the subsequent Sūtras.

Avidyā kṣetram uttareṣāṃ prasupta-tanu-vicchinnodārāṇām.

ignorance or lack of awareness of Reality

ignorance or lack of awareness of Reality  field; source

field; source  of the following ones

of the following ones  (of) dormant; sleeping

(of) dormant; sleeping  attenuated; thin

attenuated; thin  scattered; dispersed; alternating

scattered; dispersed; alternating  (and) expanded; fully operative.

(and) expanded; fully operative.

4. Avidyā is the source of those that are mentioned after it, whether they be in the dormant, attenuated, alternating or expanded condition.

This Sūtra gives two important facts concerning the nature of the Kleśas. The first is their mutual relationship. Avidyā is the root-cause of the other four Kleśas which in their turn produce all the miseries of human life. A closer study of the nature of the other four Kleśas will show not only that they can grow only on the soil of Avidyā but also that the five Kleśas form a connected series of causes and effects. The relation existing between the five Kleśas may be likened to the relation of root, trunk, branches, leaves and fruit in a tree. The conclusion that the five Kleśas are related to one another in this manner is further strengthened by 11-10 but we shall discuss this question in dealing with that Sūtra.

The other idea in this Sūtra is the classification of the states or conditions in which these Kleśas may exist. These four states are defined as (1) dormant, (2) attenuated, (3) alternating, (4) expanded. The dormant condition is that in which the Kleśa is present but in a latent form. It cannot find expression for lack of proper conditions for its expression and its kinetic energy has become potential. The attenuated condition is that in which the Kleśa is present in a very feeble or tenuous condition. It is not active but can become active in a mild degree on a stimulus being applied. In the fully expanded condition the Kleśa is fully operative and its activity is all too apparent like the waves on the surface of the sea in a storm. The alternating condition is that in which two opposite tendencies overpower each other alternately as in the case of two lovers who sometimes become angry and affectionate alternately. The feelings of attraction and repulsion alternate, though fundamentally they are based on attachment.

It is only in the case of the advanced Yogis that the Kleśas are present in the dormant form. In the case of ordinary people, the Kleśas are present in the other three conditions, depending upon external circumstances.

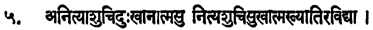

Anityāsuci-duḥkhānātmasu nitya-śuci-sukhātmakhyātir avidyā.

(of) non-eternal

(of) non-eternal  impure

impure  misery; pain; evil

misery; pain; evil  (and) non-Ātman;, not-Self

(and) non-Ātman;, not-Self  eternal

eternal  pure

pure  happiness; pleasure; good

happiness; pleasure; good  (and) Self

(and) Self  knowledge; consciousness, (taking)

knowledge; consciousness, (taking)  ignorance.

ignorance.

5. Avidyā is taking the non-eternal, impure, evil and non-Ātman to be eternal, pure, good and Ātman respectively.

This Sūtra defines Avidyā the root of the Kleśas. It is quite obvious that the word Avidyā is not used in its ordinary sense of ignorance or lack of knowledge, but in its highest philosophical sense. In order to grasp this meaning of the word we have to recall the initial process whereby, according to the Yogic philosophy, consciousness, the Reality underlying manifestation, becomes involved in matter. Consciousness and matter are separate and utterly different in their essential nature but for reasons which will be discussed in the subsequent Sūtras they have to be brought together. How can Ātmā, which is eternally free and self-sufficient, be made to assume the limitations which are involved in the association with matter? It is by depriving it of the knowledge or rather the awareness of its eternal and self-sufficient nature. This deprivation of knowledge of its true nature which involves it in the evolutionary cycle is brought about by a transcendent power inherent in the Ultimate Reality which is called Māyā or the Great Illusion.

Of course, this simple statement of a transcendent truth can give rise to innumerable philosophical questions such as ‘Why should it be necessary for the Ātmā which is self-sufficient to be involved in matter?’ ‘How is it possible for the Ātmā which is eternal to become involved in the limitations of Time and Space?’ There is no real answer to such ultimate questions although many answers, obviously absurd, have been suggested by different philosophers from time to time. According to those who have come face to face with Reality and know this secret, the only method by which this mystery can be unravelled is to know the Truth which underlies manifestation and which by its very nature is incommunicable.

As a result of the illusion in which consciousness gets involved it begins to identify itself with the matter with which it becomes associated. This identification becomes increasingly fuller as consciousness descends further into matter until the turning point is reached and the upward climb in the opposite direction begins. The reverse process of evolution in which consciousness gradually extricates itself, as it were, from matter results in an increasing realization of its Real nature and ends in complete Self-realization in Kaivalya. It is this fundamental privation of knowledge of its Real, nature, which begins with the evolutionary cycle, is brought about by the power of Māyā, and ends with the attainment of Liberation in Kaivalya, which is called Avidyā. Avidyā has nothing to do with the knowledge which we acquire through the intellect and which refers to the things concerning the phenomenal worlds. A man may be a great scholar, a walking encyclopaedia as we say, and yet may be so completely immersed in the illusions created by the mind that he may stand much below a simple-minded Sādhaka who is partially aware of the great illusions of the intellect and the life in these phenomenal worlds. The Avidyā of the latter is much less than that of the former in spite of the tremendous difference in knowledge pertaining to the intellect. This absence of awareness of our true nature results in the inability to distinguish between the eternal, pure, blissful Self and the non-eternal, impure and painful not-Self.

The word ‘eternal’ here means as usual the state of consciousness which is above the limitation of time as we know it as a succession of phenomena. ‘Pure’ refers to the purity of consciousness as it exists unaffected and unmodified by matter which imposes upon it the limitation of the three Guṇas and consequent illusions. ‘Blissful’, of course, refers to the Ānanda or bliss of the Ātmā which is inherent in it and which is independent of any external source or circumstance. The privation of this Sukha or bliss which is inevitable when consciousness is identified with matter is Duḥkha or misery. All these three attributes, which have been mentioned in the distinction between the Self and the not-Self, are merely illustrative and not exhaustive because it is impossible to define the nature of the Self and to distinguish it from the not-Self in terms of the limited conceptions of the intellect. The central idea to be grasped is that the Ātmā in its purity is fully conscious of its Real nature. Progressive involution in matter deprives it of this Self-knowledge in increasing degree and it is the privation of this knowledge which is called Avidyā. As the matter is one pertaining to the realities beyond the scope of the intellect it is not possible to understand it through the medium of the intellect alone.

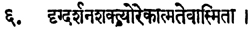

Dṛg-darśana-śaktyor ekātmatevāsmitā.

(of) power of consciousness; seer; Puruṣa

(of) power of consciousness; seer; Puruṣa  (and) power of seeing; cognition; Buddhi

(and) power of seeing; cognition; Buddhi  identity; blending together;

identity; blending together;  as if

as if  ‘I-am-ness’

‘I-am-ness’

6. Asmītā is the identity or blending together, as it were, of the power of consciousness (Puruṣa) with the power of cognition (Buddhi).

Asmitā is defined in this Sūtra as the identification of the power of consciousness with the power of cognition, but as the power of cognition always works through a vehicle, in its wider and more intelligible meaning it may be considered as the identification of consciousness with the vehicle through which it is being expressed. This is a very important and interesting idea which we should understand thoroughly if we want to master the technique of liberating consciousness from the limitations under which it works in the ordinary individual. The Saṃskṛta word Asmitā is derived from Asmi which means literally ‘I am’. ‘I am’ represents the pure awareness of Self-existence and is therefore the expression or Bhāva, as it is called, of pure consciousness or the Puruṣa. When the pure consciousness gets involved in matter and owing to the power of Māyā, knowledge of its Real nature is lost the pure ‘I am’ changes into ‘I am this’ where ‘this’ may be the subtlest vehicle through which it is working, or the grossest vehicle, namely the physical body. The two processes, namely the loss of awareness of its Real nature and the identification with the vehicles, are simultaneous. The moment consciousness identifies itself with its vehicles it has fallen from its pure state and it becomes bound by the limitations of Avidyā, or we may say that the moment the veil of Avidyā falls on consciousness its identification with its vehicles results immediately, though philosophically Avidyā must precede Asmitā.

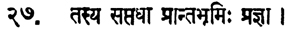

The involution of consciousness in matter is a progressive process and for this reason though Avidyā and Asmitā begin where the thinnest veil of Māyā involves pure consciousness in the subtlest vehicle, the degree of Avidyā and Asmitā goes on increasing as the association of consciousness with matter becomes more and more strengthened. As consciousness descends into one vehicle after another the veil of Avidyā becomes, as it were, thicker and the tendency to identify oneself with the vehicle becomes stronger and grosser. On the other hand, when the reverse process takes place and consciousness is released from its limitations in its evolutionary upward climb, the veil of Avidyā becomes thinner and the resulting Asmitā weaker and subtler. This evolution on the upward arc takes place in seven definite and clearly marked stages as is indicated in II-27. These stages correspond to the transference of consciousness from one vehicle to a subtler vehicle.

Let us now come down from the abstract principles and consider the problem in relation to things with which we are familiar and which we can understand more easily. Let us consider the problem of the expression of consciousness through the physical body. We should remember, in considering this question that the consciousness which is normally expressed through the physical body is not pure unmodified consciousness being involved in a vehicle. It has already passed through several such involutions and it is already heavily loaded, as it were, when it seeks expression through the outermost or grossest vehicle. It is therefore consciousness conditioned by the limitations of all the intervening vehicles which form a kind of bridge between it and the physical body. But as the process of involution and consequent identification is in essence the same at each stage of involution, we can get some idea of the underlying principles even though the expression of consciousness through the physical body is complicated by the factors referred to above.

Coming back to our problem we then see that the association of consciousness, conditioned as mentioned above, with the physical body must lead to this identification with the vehicle and the language which is used by all of us in common intercourse reflects this fully. We always use such expressions as ‘I see’, ‘I hear’, ‘I go’, ‘I sit’. In the case of the savage and the child this identification with the body is so complete that there is not the slightest feeling of discrepancy in using such language. But the educated and intelligent man, whose identification with the body is not quite complete and who feels to a certain extent that he is different from the body, is aware at least in a vague manner that it is not he who sees, hears, walks and sits. These activities belong to the physical body and he is merely witnessing them through his mind. Still, from force of habit and disinclination to go deeper into the matter, or from fear of appearing odd in using the correct language he continues to use the common phraseology. So deep rooted is this identification that even physiologists, psychologists and philosophers, who are supposed to be familiar with the mechanism of sense-perception and intellectually recognize the mere instrumentality of the physical body, are hardly actively aware of this tendency and may identify themselves with the body completely. It is worth noting that mere intellectual knowledge with regard to such patent facts does not by itself enable a person to separate himself from his vehicles. Who has more detailed knowledge with regard to the physical body and its functions than a doctor who has dissected hundreds of bodies and knows that it is a mere mechanism? One would expect that a doctor at least, from whom nothing inside the body is hidden, will be above this tendency to regard himself as the body. But is a doctor in any way better off in this respect than a layman? Not at all. This is not a matter of ordinary seeing and understanding at all.

Asmitā or identification with a vehicle is not a simple but a very complex process and has many aspects. The first aspect we may consider is identification with the powers and faculties associated with the vehicles. For example, when a person says ‘I see’ what really happens is that the faculty of sight is exercised by the body through the eye and the in-dwelling entity becomes merely aware of the result, i.e. the panorama presented before the eye. Again, when he says, ‘I walk’ what really happens is that the will working through the mind moves the body on its legs like a portable instrument and the in-dwelling entity identifying himself with the movement of the body says, ‘I walk’.

The second aspect is the association of the subtler vehicle in this process of identification where a compound Asmitā—if such a phrase can be used—is produced. Thus when a person says he has a headache what is really happening is that there is a slight disorder in the brain. This disorder by its reaction on the next subtler vehicle through which sensations and feelings are felt produces the sensation of pain. The in-dwelling entity identifies himself with this joint product of these two vehicles and this results in ‘his’ having a headache, although a little thought will show him that it is not he but the vehicle which is having the pain of which he is aware. The same thing working at a somewhat higher level produces such reactions as ‘I think’, ‘I approve’. It is the mind which thinks and approves and the consciousness becomes merely aware of the thought process which is reflected in the physical body. Ambition, pride and similar unpleasant traits of human character are merely highly developed and perverted forms of this tendency to identify ourselves with the workings of the mind.

A third aspect which may be considered in this process of identification is the inclusion of other accessories and objects in the environment. The physical body becomes a centre round which get associated a number of objects which in smaller or greater degree become part of the ‘I’. These objects may be animate or inanimate. The other bodies which are born of one’s body become ‘my children’. The house in which one’s body is kept becomes ‘my house’. So round the umbra (total shadow) created by Asmitā with the body is a penumbra (partial shadow) containing all those objects and persons which ‘belong’ to the ‘I’ working through the body and they produce the attitude or Bhāva of ‘my’ and ‘mine’.

The above brief and general discussion of Asmitā associated with the physical body will give some idea to the student with regard to the nature of this Kleśa. Of course, Asmitā manifesting through the physical body is the grossest form of the Kleśa and as we try to study the working of this tendency in the subtler vehicles we find it more and more elusive and difficult to deal with. Any thoughtful man can separate himself in thought from his physical body and see that he is not the bag of flesh, bones and marrow with the help of which he comes in contact with the physical world. But few can separate themselves from their intellect and realize that their opinions and ideas are mere thought patterns produced by their mind just like the thought patterns produced by other minds. The reason why we take interest in and attach so much importance to our opinions lies, of course, in the fact that we identify ourselves with our intellect. Our thoughts, opinions, prejudices and predilections are part of our mental possessions, children of our mind, and that is why we feel and show such undue and tender regard for them.

Of course, there are levels of consciousness even beyond that of the intellect. In all these Asmitā is present though it becomes subtler and more refined as we leave one vehicle after another. It is no use dealing with these subtler manifestations of Asmitā here because unless one can transcend the intellect and function in these super-intellectual fields one cannot really understand them.

Although the question of destroying the Kleśas will be dealt with later in subsequent Sūtras there is one fact which may be usefully pointed out here. Many methods have been suggested whereby this tendency to identify ourselves with our vehicles may be gradually attenuated. Many of these methods are quite useful and do help us in a certain measure to disentangle our consciousness from our vehicles. But it has to be borne in mind that complete dissociation from a vehicle takes place only when consciousness is able to leave the vehicle deliberately and consciously and function in the next subtler vehicle (of course, with all the still subtler vehicles present in the background). When the Jivātmā is able to leave a vehicle at will and ‘see’ it separate from himself then only is the false sense of identification completely destroyed. We may meditate for years trying to separate ourselves in thought from the body but the result of this will not be as great as one experience of leaving it consciously and seeing it actually separate from ourselves. We shall, of course, re-enter that body and assume all its limitations but it can never again exercise on us the same illusory influence as it did before. We have realized that we are different from the body. For the advanced Yogi who can and does leave his body every now and then and can function independently of it in a routine manner, it is just like a dwelling house. The very idea of identifying himself with the body will appear absurd to him. It will be seen, therefore, that practice of Yoga is the most effective means of destroying Asmitā completely and permanently. As the Yogi leaves one vehicle of consciousness after another in Samādhi he destroys progressively the tendency to identify himself with those vehicles and with the destruction of Asmitā in this manner the veil of Avidyā automatically becomes thinner.

Sukhānuśayī rāgaḥ.

pleasure; happiness

pleasure; happiness  accompanying; resulting (from)

accompanying; resulting (from)  attraction; liking.

attraction; liking.

7. That attraction, which accompanies pleasure, is Rāga.

Rāga is defined in this Sūtra as the attraction which one feels towards any person or object when any kind of pleasure or happiness is derived from that person or object. It is natural for us to get attracted in this manner because the soul in bondage, having lost the direct source of Ānanda within, gropes after Ānanda in the external world and anything which provides even a shadow of this in the form of ordinary happiness or pleasure becomes dear to it. If we are attracted to any person or object we shall always find on scrutiny that the attraction is due to some kind of pleasure, physical, emotional or mental. We may be addicted to a particular kind of food because we find it pleasant. We may be attached to a person because we derive from him some kind of pleasure, physical or emotional. We may be devoted to a particular pursuit because it gives us intellectual satisfaction.

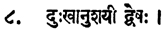

Duḥkhānuśayī dveṣaḥ.

pain;

pain;  accompanying; resulting (from),

accompanying; resulting (from),  repulsion.

repulsion.

8. That repulsion which accompanies pain is Dveṣa.

Dveṣa is the natural repulsion felt towards any person or object which is a source of pain or unhappiness to us. The essential nature of the Self is blissful and therefore anything which brings pain or unhappiness in the outer world makes the outer vehicles recoil from that thing. What has been said about Rāga is applicable to Dveṣa in an opposite sense because Dveṣa is only Rāga in the negative, the two together forming a pair of opposites.

As these two Kleśas form the most prominent part of the fivefold tree which provides the innumerable fruits of human misery and suffering it is worthwhile taking note of a few facts concerning them.

(1) The attractions and repulsions which bind us to innumerable persons and things, in the manner indicated above, condition our life to an unbelievable extent. Unconsciously or consciously we think, feel and act according to hundreds of these biases produced by these invisible bonds and there is hardly any freedom left for the individual to act, feel and think freely. The conditioning of the mind which takes place when we are under the domination of any overpowering attraction or repulsion is recognized, but few people have any idea of the distortion produced in our life by the less prominent attractions and repulsions or the extent to which our life is conditioned by them.

(2) These attractions and repulsions bind us down to the lower levels of consciousness because it is only in these levels that they can have free play. It is a fundamental law of life that we find ourselves sooner or later where our conscious or unconscious desires can be satisfied. Since these attractions and repulsions are really the breeders of desires pertaining to the lower life they naturally keep us tied down to the lower worlds where consciousness is under the greatest limitations.

(3) The repulsions bind us as much as the attractions. Many people are vaguely aware of the binding nature of the attractions but few can understand why repulsions should bind an individual. But repulsions bind as much as the attractions because they also are the expression of a force connecting the two components which are repelled from each other. We are tied to the person we hate perhaps more firmly than to the person we love, because the personal love can be transformed into impersonal love easily and then loses its binding power. But it is not so easy to transmute the force of hatred and the poison generated by it is removed from one’s nature with great difficulty. As Rāga and Dveṣa form a pair of opposites we cannot transcend one without transcending the other. They are like two sides of a coin. In the light of what is said above it will be seen that Vairāgya is not only freedom from Rāga but also freedom from Dveṣa. A free and unconditioned mind does not oscillate from side to side. It remains stationary at the centre.

(4) Attractions and repulsions really belong to the vehicles but owing to the identification of consciousness with its vehicles we feel that we are being attracted or repelled. When we begin to control and eliminate these attractions and repulsions we gradually become aware of this fact and this knowledge then enables us to control and eliminate them more effectively.

(5) That Rāga and Dveṣa in their gross form are responsible for much of human misery and suffering will become apparent to anyone who can view life dispassionately and can trace causes and effects intelligently. But only those who systematically try to attenuate the Kleśas by means of Kriyā-Yoga can see the subtler workings of these Kleśas, how they permeate the whole fabric of our worldly life and prevent us from having any peace of mind.

Svarasavāhī viduṣo ’pi tathā rūḍho ’bhini-veśah.

sustained by its own forces; flowing on automatically

sustained by its own forces; flowing on automatically  the learned (or wise)

the learned (or wise)  even

even  in that way

in that way  riding; dominating

riding; dominating  great fear of death; strong desire for life; thorough infiltration (of the mind); will-to-live.

great fear of death; strong desire for life; thorough infiltration (of the mind); will-to-live.

9. Abhiniveśa is the strong desire for life which dominates even the learned (or the wise).

The last derivative of Avidyā is called Abhiniveśa. It is generally translated as desire for life or will-to-live. That every human being, in fact every living creature, wants to continue to live is, of course, a fact with which everyone is familiar. We sometimes see people who have nothing to gain from life. Their life is one long drawn-out misery and yet their attachment to life is as great as ever. The reason for this apparent anomaly is, of course, that the other four Kleśas which result in desire for life or Abhiniveśa are in full operation even in the absence of unfavourable external circumstances.

There are two points in this Sūtra which require some explanation. First, that this strong attachment to life which is universal is well established even in the learned. One may expect ordinary people to feel this attachment but a wise man at least who knows all about the realities of life may be expected to sit lightly on life. But as a matter of fact, this is not so. The philosopher who is well versed in all the philosophies of the world and knows intellectually all the deeper problems of life is as much attached to life as the ordinary person who is ignorant about these things. The reason why Patañjali has pointed out this fact definitely lies perhaps in his intention to bring to the notice of the would-be Yogi that mere knowledge of the intellect (Viduṣaḥ here really means the learned and not the wise) is in itself inadequate for freeing a man from this attachment to life. Unless and until the tree of Kleśas is destroyed, root and branch, by a systematic course of Yogic discipline the attachment to life in smaller or greater degree will continue in spite of all the philosophies we may know or preach. The would-be Yogi, therefore, places no reliance on such theoretical knowledge. He treads the path of Yoga which alone can bring freedom from the Kleśas.

The second point to be noted in this Sūtra is contained in the phrase Svarasavāhī which means sustained by its own inherent force or potency. The universality of Abhiniveśa shows that there is some constant and universal force inherent in life which automatically finds expression in this ‘desire to live’. The desire to live is not the result of some accidental development in the course of evolution. It seems to be an essential feature of that process. What is this all-powerful force which seems to underlie the current of life and which makes every living creature stick to life like a leech all the time? According to the Yogic philosophy this force is rooted in the very origin of things and it comes into play the moment consciousness comes in contact with matter and the evolutionary cycle begins. As was pointed out in II-4 Avidyā is the root of all the Kleśas and Abhiniveśa is merely the fruit or the final expression of the chain of causes and effects set in motion with the birth of Avidyā and the involution of consciousness in matter.

It was pointed out earlier that the different Kleśas are not unconnected with one another. They form a sort of series beginning with Avidyā and ending with Abhiniveśa. This view is supported by II-10 according to which the method by which the subtle forms of Kleśas can be destroyed is by reversing the process by which they are produced. According to this view, then, Abhiniveśa is merely the final phase in the development of the Kleśas and that is why it is Svarasavāhī. Until the initial cause disappears the subsequent effects must continue to appear in an unending flow.

In the connected series of Kleśas, Rāga and Dveṣa appear as the immediate cause of attachment to life. It follows from this that the greater the play of attractions and repulsions in the life of an individual the greater must be his attachment to life. Observation of life shows that this is to a great extent true. It is people who are under the domination of most violent attractions and repulsions who are most attached to life. We also find that in old age these attractions and repulsions temporarily lose their force to some extent and pari passu the desire for life also becomes comparatively feebler.

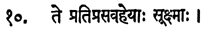

Te pratiprasava-heyāḥ sūkṣmāḥ.

they

they  re-absorption; re-mergence; resolution into respective cause or origin

re-absorption; re-mergence; resolution into respective cause or origin  capable of being reduced or avoided or abolished

capable of being reduced or avoided or abolished  subtle.

subtle.

10. These, the subtle ones, can be reduced by resolving them backward into their origin.

In II-10 and II-11 Patañjali gives the general principles of first attenuating the Kleśas and finally destroying them. The Kleśas can exist in two states, active and potential. In their active state they can be recognized easily by their outer expressions and the definite awareness which they produce in the mind of the Sādhaka. In the case of a person who is in a fit of anger it is easy to see that Dveṣa is in full operation. The same person when he subjects himself to a rigid self-discipline acquires the capacity to keep himself absolutely calm and without repulsion towards any one and thus reduces this Kleśa to a potential condition. Dveṣa has ceased to function but its germs are still there and, given very favourable conditions, can be made active again. Their power has become potential but not completely destroyed. The transition from the fully active to the perfectly dormant condition takes place through a number of stages which have been pointed out in II-4. Through the practice of Kriyā-Yoga they can be attenuated progressively until they become quite dormant, incapable of being aroused by ordinary stimuli from the external world. But given extraordinary conditions they can be made active again. So we have to deal with two problems in the complete elimination of the Kleśas, first to reduce them to the inactive or Sūkṣma state and then to destroy even their potential power. The first is referred to generally as reducing the Kleśas to the form of ‘seeds’ which under favourable conditions have still the power to grow into a tree, and the second as ‘scorching the seeds’ so that while they may retain the outer form of the ‘seeds’ they have really become incapable of germinating and growing into a tree.

The problem of reducing the Kleśas to the condition of ‘seeds’ is itself divisible under two sub-heads, that of reducing the fully active forms to the attenuated forms (Tanu) and then reducing the latter to the extremely inactive condition (Prasupta) from which they cannot be aroused easily. Since the first of these two problems is the more important and fundamental in its nature Patañjali has dealt with it first in II-10. The second problem of reducing the active forms of the Kleśas to the partially latent condition, being comparatively easier, is dealt with in II-41, though in Sādhanā it really precedes the first problem.

In II-10 the method of reducing the Kleśas which have been attenuated to the dormant stage has been hinted at. The phraseology used by Patañjali is extremely apt and expressive but many people find it difficult to understand the meaning of this pregnant Sūtra. The phrase Pratiprasava means involution or re-absorption of effect into cause or reversing the process of Prasava or evolution. If a number of things are derived in a series from a primary thing by a process of evolution they can all be reduced to the original thing by a counter-process of involution and such a counter process is called Pratiprasava. Let us consider the underlying significance of this phrase in the present context.

We have seen already that the five Kleśas mentioned in II-3 are not independent of each other but form a series beginning with Avidyā and ending with Abhiniveśa. The process of the development of Avidyā into its final expression Abhiniveśa is a causal process, one stage naturally and inevitably leading to the next one. It is therefore inevitable that if we want to remove the final element of this fivefold series we must reverse the process whereby each effect is absorbed in its immediate cause and the whole series disappears. It is a question of removing all or none. This means that Abhiniveśa should be traced back to Rāga-Dveṣa, Rāga-Dveṣa to Asmitā, Asmitā to Avidyā, and Avidyā to Enlightenment. This tracing backward is not merely an intellectual recognition but a realization which nullifies the power of the Kleśas to affect the mind of the Yogi. This realization can come to a certain extent on the physical plane but is attained in its fullness on the higher planes when the Yogi can rise in Samādhi to those planes. It will, therefore, be seen from what has been said above that there is no short-cut to the attenuation and final destruction of the Kleśas. It involves the whole technique of Yogic discipline.

The fact that the subtle forms of Kleśas remain in their ‘seed’ form even after they have been attenuated to the extreme limit is of great significance. It means that the Sādhaka is not free from danger until he has crossed the threshold of Kaivalya and reached the final goal. As long as these ‘seeds’ lurk within him there is no knowing when he may become their victim. It is these unscorched ‘seeds’ of Kleśas which account for the sudden and unexpected fall of Yogis after they have reached great heights of illumination and power. This shows the necessity of exercising the utmost discrimination right up to the very end of the Path.

When the latent forms of Kleśas have been attenuated to the utmost limit and the resulting tendencies have been made extremely feeble—brought almost to the zero level—the question arises, ‘How to destroy the potentiality of these tendencies so that there may be no possibility of their revival under any circumstances?’ How to scorch the ‘seeds’ of Kleśas so that they cannot germinate again? This is a very important question for the advanced Yogi because his work has not been completed until this has been done. The answer to this question follows from the very nature of the Kleśas which has been discussed previously. If the Kleśas are rooted in Avidyā they cannot be destroyed until Avidyā is destroyed. This means that no freedom from the subtlest forms of the Kleśas is possible until full Enlightenment of Kaivalya is attained through the practice of Dharma-Megha-Samādhi. This conclusion is confirmed by IV-30 according to which freedom from Kleśas and Karmas is obtained only after Dharma-Megha-Samādhi which precedes the attainment of Kaivalya.

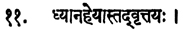

Dhyāna-heyās tad-vṛttayaḥ.

(by) meditation

(by) meditation  (Kleśas which are) to be avoided

(Kleśas which are) to be avoided  their modifications; ways of existing; activities.

their modifications; ways of existing; activities.

11. Their active modifications are to be suppressed by meditation.

This Sūtra gives the method of dealing with the Kleśas in the preliminary stage when they have to be reduced from an active to a passive state. The means to be adopted are given in one word Dhyāna. It is therefore necessary to understand the meaning of this word in its full scope. The word Dhyāna, of course, literally means meditation or contemplation as explained elsewhere but here it obviously stands for a rather comprehensive self-discipline of which meditation is the pivot. It is easy to see that a Sādhaka who is under the domination of Kleśas in their active form will have to attack the problem from many sides at once. In fact, the whole technique of Kriyā-Yoga will have to be utilized for this purpose, for one of the two objects of Kriyā-Yoga is to attenuate the Kleśas and the reduction of the Kleśas from their active to the passive form is the first step in this attenuation. Svādhyāya, Tapas and Iśvara-praṇidhāna, all the three elements of Kriyā-Yoga, have therefore to be used in this work. But the essential part of all these three is really Dhyāna, the intensive concentration of the mind in order to understand the deeper problems of life and to solve them effectively for the realization of one’s main objective. Even Tapas, the element of Kriyā-Yoga which outwardly seems to involve merely going through certain self-disciplinary and purificatory exercises, depends for its effectiveness to a large extent on Dhyāna. For, it is not the mere external performance of the act which brings about the desired result but the inner concentration of purpose and the alert mind which underlie the act. If these latter are not present the outer action will be of no avail. No success in Yoga is possible unless all the energies of the soul are polarized and harnessed for achieving the central purpose. So the word Dhyāna in II-11 implies all mental processes and exercises which may help the Sādhaka to reduce the active Kleśas to the passive condition. It may include reflection, brooding over the deeper problems of life, changing habits of thought and attitudes by means of meditation (II-33), Tapas as well as meditation in the ordinary sense of the term.

It is necessary to note in this connection that reducing the Kleśas to a latent or passive condition does not mean merely bringing them to a temporary state of quiescence. Violent disturbances of the mind and emotions which result from the activity of the Kleśas (Kleśa-Vṛtti) are not always present and we all pass through phases in which Kleśas like Rāga-Dveṣa seem to have become latent. A Sādhaka may retire for sometime into solitude. As long as he is cut off from all kinds of social relationships, Rāga and Dveṣa will naturally become inoperative but that does not mean that he has reduced these to a latent state. It is only their outer expression which has been suspended and the moment he resumes his social life these Kleśas will re-assert themselves with their usual force. Reducing the Kleśas to the latent state means making the tendencies so feeble that they are not easily aroused, though they have not yet been rooted out.

Another point which may be noted is that attacking one particular form or expression of a Kleśa is not of much avail, though in the beginning this may be done to gain some knowledge of the working of the Kleśas and the technique of mastering them. A Kleśa can assume innumerable forms of expression and if we merely suppress one of its expressions it will assume other forms. It is the general tendency which has to be tackled and it is this isolation, as it were, of this tendency and tackling it as a whole which tests the intelligence of the Sādhaka and determines the success of the endeavour.

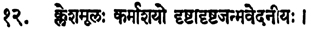

Kleśa-mūlaḥ karmāśayo dṛṣṭādṛṣṭa-janma-vedanīyaḥ.

rooted in Kleśas

rooted in Kleśas  reservoir of Karmas; the vehicle of the seeds of Karma

reservoir of Karmas; the vehicle of the seeds of Karma  seen; present

seen; present  unseen; future

unseen; future  lives

lives  to be known; to be experienced.

to be known; to be experienced.

12. The reservoir of Karmas which are rooted in Kleśas brings all kinds of experiences in the present and future lives.

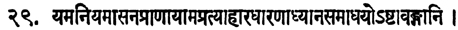

Sūtras 12, 13 and 14 give in a very concise and lucid manner the essential features of the twin laws of Karma and Reincarnation, the well-known doctrines formulating the Universal Moral Law and cycle of births and deaths underlying human life. As the students of Yoga are generally familiar with the broad aspects of these doctrines it is not necessary to discuss them here and we shall confine ourselves to the particular aspects referred to in these three Sūtras. It may be pointed out at the very outset that Patañjali has not attempted to give us a general idea concerning the Laws of Karma and Reincarnation. His object is merely to show the underlying cause of human misery so that we may be able to appreciate the means adopted in Yogic discipline for its effective removal. He, therefore, takes only those particular aspects of these laws which are needed for his argument. But, incidentally, he has given in three brief Sūtras the very essence of these all-embracing laws.

The first idea given in II-12 which we have to note is that Kleśas are the underlying cause of the Karmas we generate by our thoughts, desires and actions. Each human soul goes through a continuous series of incarnations reaping the fruits of thoughts, desires, and actions done in the past and generating, during the process of reaping, new causes which will bear their fruits in this or future lives. So every human life is like a flowing current in which two processes are at work simultaneously, the working out of Karmas made in the past and the generation of new Karmas which will bear fruit in the future. Each thought, desire, emotion and action produces its corresponding result with mathematical exactitude and this result is recorded naturally and automatically in our life’s ledger.

What is the nature of this recording mechanism upon which depends the working out of causes and effects with mathematical precision? The answer to this question is contained only in one word, Karmāśaya, given in this Sūtra. This word means literally the reservoir or sleeping place of Karmas. Karmāśaya, obviously, refers to the vehicle in our inner constitution which serves as the receptacle of all the Saṃskāras or impressions made by our thoughts, desires, feelings and actions. This vehicle serves as a permanent record of all that we have thought, felt or done during the long course of evolution extending over a series of lives and provides patterns and contents of the successive lives. People who are familiar even with elementary physiology should find no difficulty in understanding and appreciating this idea because the impressions produced in our brain by our experiences on the physical plane provide an exact parallel. Everything which we have experienced through our sense-organs is recorded in the brain and can be recovered in the form of memory of those experiences. We cannot see these impressions and yet we know that they exist.

Students who are familiar with Hindu philosophical thought will find no difficulty in identifying this Karmāśaya with the Kāraṇa Śarira or ‘causal body’ in the Vedāntic classification of our inner constitution. This is one of the subtle vehicles of consciousness which lies beyond the Manomaya Kośa and is so called because it is the source of all causes which will be set in motion and will mould our present and future lives. It is the receptacle into which the effects of all that we do are being constantly poured and being transformed into causes of experiences which we shall go through in this and future lives.

Now, the important point to note here is that though this ‘causal’ vehicle is the immediate or effective cause of the present and future lives and from it, to a great extent, flow the experiences which constitute those lives, still, the real or ultimate cause of these experiences are the Kleśas. Because, it is the Kleśas which are responsible for the continuous generation of Karmas and the causal vehicle merely serves as a mechanism for adjusting the effects of these Karmas.

Sati mūle tad-vipāko jāty-āyur-bhogāḥ.

there being the root

there being the root  (of) it (Karmāśaya)

(of) it (Karmāśaya)  fruition; ripening

fruition; ripening  class

class  (span of) life

(span of) life  (and) experiences.

(and) experiences.

13. As long as the root is there it must ripen and result in lives of different class, length and experiences.

As long as the Kleśas are operating in the life of an individual the vehicle of Karmas will be continually nourished by the addition of new causal impressions and there is no possibility of the series of lives coming to an end. If the root remains intact the Saṃskāras in the causal vehicle will naturally continue to ripen and produce one life after another with its inevitable misery and suffering. Though the nature and content of experiences gone through by human beings in their lives is of infinite variety, Patañjali has classified these under three heads (1) class, (2) length of life, and (3) pleasant or unpleasant nature of the experiences. These are the principal features which determine the nature of a life. First, Jāti or class. This determines the environment of the individual and thus his opportunities and the type of life which he will be able to lead. A man born in a slum has not the same opportunities as a man born among cultured people. So the kind of life a person has is determined in the first place by Jāti.

The second important factor is the length of life. This naturally determines the total number of experiences. A life cut short in childhood contains a comparatively smaller number of experiences than a long life running its normal course. Of course, since the successive lives of an individual form one continuous whole, from the larger point of view, a short life intervening in this manner does not really matter very much. It is as if a person could not have a full day for work but had to go to bed early. Another day dawns when he can continue his work as usual.

The third factor is the nature of the experiences gone through as regards their pleasant or unpleasant quality. Jāti also determines the nature of the experiences but there we consider the experiences in relation to the opportunities for the growth of the soul. Under Bhoga we consider experiences in relation to their potentiality to bring pain or pleasure to the individual. There are some people who are well placed in life but have a difficult time—nothing but suffering and unhappiness from birth to death. On the other hand, we may have a life lived in comparatively poor circumstances but the experiences may be pleasant all along. The pleasures and pains which we have to bear are not entirely dependent upon our Jāti. There is a personal factor involved as we can ourselves see by observing the lives of people around us.

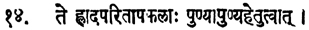

Tc hlāda-paritāpa-phalāḥ puṇyāpuṇya-hetutvāt.

they

they  joy

joy  (and) sorrow

(and) sorrow  (having for their) fruit

(having for their) fruit  merit as opposed to sin or demerit

merit as opposed to sin or demerit  demerit; sin (

demerit; sin ( and

and  are the assets and liabilities superphysically registered in the soul)

are the assets and liabilities superphysically registered in the soul)  being caused by; on account of.

being caused by; on account of.

14. They have joy or sorrow for their fruit according as their cause is virtue or vice.

Upon what depends the nature of the experiences we have to go through in life? Since everything in the Universe works according to a hidden and immutable law it cannot be due to mere chance that some of these experiences are joyful and others are sorrowful. What determines this pleasurable or painful quality of the experiences? II-14 gives an answer to this question. The pleasurable or painful quality of experiences which come in our life is determined by the nature of the causes which have produced them. The effect is always naturally related to the cause and its nature is determined by the cause. Now, those thoughts, feelings and actions which are ‘virtuous’ give rise to experiences which are pleasant while those which are ‘vicious’ give rise to experiences which are unpleasant. But we must not take the words ‘virtuous’ and ‘vicious’ in their narrow, orthodox religious sense but in the wider and scientific sense of living in conformity with the great Moral Law which is universal in its action and mathematical in its expression. In Nature the effect is always related to the cause and corresponds exactly to the cause which has set it in motion. If we cause a little purely physical pain to somebody it is reasonable to suppose that the fruit of our action will be some experience causing a corresponding physical pain to us. It cannot be a dreadful calamity causing terrible mental agony. This will be unjust and the Law of Karma is the expression of the most perfect justice that we can conceive of. Since Karma is a natural law and natural laws work with mathematical precision we can to a certain extent predict the Kārmic results of our actions and thoughts by imagining their consequences. The Kārmic result, or ‘fruit’ as it is generally called, of an action is related to the action as a photographic copy is related to its negative, though the compounding of several effects in one experience may make it difficult to trace the effects to their respective causes. The orthodox religious conceptions of hell and heaven, in which are provided rewards and punishments without any regard for the natural relationship of causes and effects, are sometimes absurd in the extreme though they do, in a general way, relate virtue to pleasure and vice to pain.

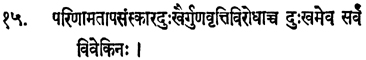

Pariṇāma-tāpa-saṃskāra-duḥkhair guṇa-vṛtti-virodhāc ca duṇkham eva sarvaṃ vivekinaḥ.

(on account of) change

(on account of) change  acute anxiety; suffering

acute anxiety; suffering  impression; stamping with a tendency

impression; stamping with a tendency  pains (three causes mentioned above)

pains (three causes mentioned above)  (between the three) Guṇas

(between the three) Guṇas  (and) modification (of the mind)

(and) modification (of the mind)  on account of opposition or conflict

on account of opposition or conflict  and

and  (is) pain; misery

(is) pain; misery  only

only  to the enlightened; to the person who has developed discrimination.

to the enlightened; to the person who has developed discrimination.

15. To the people who have developed discrimination all is misery on account of the pains resulting from change, anxiety and tendencies, as also on account of the conflicts between the functioning of the Guṇas and the Vṛttis (of the mind).

If virtue and vice beget respectively pleasurable and painful experiences the question may arise ‘Why not adopt the virtuous life to ensure in time an uninterrupted series of pleasurable experiences and to eliminate completely all painful experiences?’. Of course, for some time the results of vicious actions we have done in the past would continue to appear but if we persist in our efforts and make our life continuously and strictly moral, eliminating vice of every description, a time must come when the Saṃskāras and Karmas created from vicious thoughts and actions in the past would get exhausted and life thenceforth must become a continuous series of pleasant and happiness-giving experiences. This is a line of thought which will appeal especially to the aspirant who is having a nice time and is attached to the nice things of the world. The philosophy of Kleśas will appear to him unnecessarily harsh and pessimistic and the ideal of a completely virtuous life will seem to provide a very happy solution of the great problem of life. It will satisfy his innate moral and religious sense and ensure for him the happy and pleasant life that he really wants. The orthodox religious ideal which requires people to be good and moral so that they may have a happy life here and hereafter is really a concession to human weakness and the desire to prefer the so-called happiness in life to Enlightenment.

This idea of ensuring a happy life by means of virtue, apart from the impracticability of living a perfectly virtuous life continuously while still bound by illusion, is based on a delusion about the very nature of what the ordinary man calls happiness and II-15 explains why this is so. This is perhaps one of the most important Sūtras, if not the most important, bearing on the philosophy of Kleśas and a real grasp of the significance of the fundamental idea expounded in it is necessary not only for understanding the philosophy of Kleśas but the Yogic philosophy as a whole. Not until the aspirant has realized to some extent the illusion underlying the so-called ‘happiness’ which he pursues in the world can he really give up this futile pursuit and devote himself whole-heartedly to the task of transcending the Great Illusion and finding that Reality in which alone can one find true Enlightenment and Peace. Let the serious student, therefore, ponder carefully over the profound significance of this Sūtra.

The Sūtra in general means that all experiences are either actively or potentially full of misery to the wise person whose spiritual perception has become awakened. This is so because certain conditions like change, anxiety, habituation and conflicts between the functioning of the Guṇas and Vṛttis are inherent in life. Let us take up each of these conditions and see what it means.

Pariṇāma: means change. It should be obvious to the most unintelligent man that life as we know it is governed by a relentless law of change which is all-pervasive and applies to all things at all times. Nothing in life abides right from a Solar system to a grain of dust, and all things are in a state of flux though the change may be very slow, so slow that we may not be conscious of it. One effect of Māyā is to make us unconscious of the continuous changes which are taking place within and without us. People are afraid of death but they do not see the fact that death is merely an incident in the continuous series of changes in and around us. When the realization of this continuous, relentless change affecting everything in life dawns upon an individual he begins to realize what illusion means. This realization is a very definite experience and is one aspect of Viveka, the faculty of discrimination. The ordinary man is so immersed and completely identified with the life in which he is involved that he cannot separate himself mentally from this fast moving current. Theoretically he may recognize the law of change but he has no realization.