KAIVALYA PĀDA

Janmauṣadhi-mantra-tapaḥ-samādhi-jāḥ siddhayaḥ.

birth

birth  drugs

drugs  incantation; a group of words whose constant repetition produces specific results

incantation; a group of words whose constant repetition produces specific results  austerities; purificatory actions; penance

austerities; purificatory actions; penance  trance;

trance;  born of; are the result of

born of; are the result of  attainments; occult powers.

attainments; occult powers.

1. The Siddhis are the result of birth, drugs, Mantras, austerities or Samādhi.

Section IV of the Yoga-Sūtras provides the theoretical background for the technique of Yoga which has been dealt with in the previous three Sections. It deals with the various general problems which form an integral part of the Yogic philosophy and which must be clearly understood if the practice of Yoga is to be placed on a rational basis. The practice of Yoga is not a sort of floundering in the Unknown for attaining a vague spiritual ideal. Yoga is a Science based upon a perfect adaptation of well-defined means to an unknown but definite End. It takes into account all the factors which are involved in the attainment of its objective and provides a perfectly coherent philosophical background for the practices which are its more essential part. It is true that the doctrines which constitute this theoretical background will hardly appear rational or intelligible to people who are not familiar with this subject but that is true of any kind of knowledge which deals with problems of an unfamiliar nature. It is only those who have given considerable thought to this subject and are familiar at least with the elementary doctrines of the Yogic philosophy who can be expected to appreciate the grand and almost flawless line of reasoning which underlies the apparently disconnected topics dealt with in Section IV.

As this Section deals with many difficult topics which are apparently unconnected, it will perhaps help the student to grasp the underlying thread of reasoning running throughout the Section if a synopsis of the whole Section is given at the beginning. This will inevitably involve some repetition of ideas but such a bird’s-eye view will be definitely helpful in understanding this rather abstruse aspect of Yogic philosophy.

SYNOPSIS

Sūtra 1: This enumerates the different methods of acquiring Siddhis. Of the five methods given only the last based upon Samādhi is used by advanced Yogis in their work because it is based upon direct knowledge of the higher laws of Nature and is, therefore, under complete control of the will. The student must have noticed that all the Siddhis described in the previous Section are the result of performing Saṃyama. They are the product of evolutionary growth and thus give mastery over the whole range of natural phenomena.

Sūtras 2-3: These two Sūtras hint at the two fundamental laws of Nature which govern the flux of phenomena constituting the world of the Relative. An understanding of these two laws is necessary if we are to form a correct estimate of the functions and limitations of Siddhis. The student should not run away with the impression that it is possible for the Yogi to do anything he likes because he can bring about many results which appear miraculous to our limited vision. The Yogi is also bound by the laws of Nature and as long as his consciousness functions in the realms of Nature, it is subject to the laws which govern these realms. He has to work out his liberation from the realm of Prakṛti but he can do so only by obeying and utilizing the laws which operate in her realm.

Sūtras 4-6: The Yogi brings from his past lives, like everyone else, an enormous number of tendencies and potentialities in the form of Karmas and Vāsanās. These exist in his subtler vehicles in a very definite form and have to be worked out or destroyed before Kaivalya can be attained. These Sūtras refer to these individual vehicles which are of two types—those which are the product of evolutionary growth during successive lives and those which the Yogi can create by the power of his will. Before one can understand the methods adopted for the destruction of Karmas and Vāsanās he should have some knowledge of the mental mechanisms through which these tendencies function.

Sūtras 7-11: These deal with the modus operandi by which the impressions of our thoughts, desires and actions are produced and then worked out during the course of successive lives in our evolutionary growth. The problem for the Yogi is to stop adding to these accumulated impressions by learning the technique of Niṣkāma Karma and desirelessness and to work out those potentialities which have already been acquired in the quickest and most efficient manner. The destruction of the subtler or dormant Vāsanās depends ultimately upon the destruction of Avidyā which is the cause of attachment to life.

Sūtras 12-22: After dealing with the vehicles of the mind (Citta) and the forces (Vāsanās) which bring about incessant transformations (Vṛttis) in these vehicles Patañjali discusses the theory of mental perception, using the word ‘mental’ in its most comprehensive sense. According to him two entirely different kinds of elements are involved in mental perception. On the one hand, there must be the impact of the object upon the mind through their characteristic properties and, on the other, the eternal Puruṣa must illuminate the mind with the light of his consciousness. Unless both these conditions are simultaneously present there can be no mental perception because the mind itself is inert and incapable of perceiving. It is the Puruṣa who is the real perceiver though he always remains in the background and the illumination of the mind with the light of his consciousness makes it appear as if it is the mind which perceives. This fact can be realized only when the mind is entirely transcended and the consciousness of the Puruṣa is centred in his own, Svarūpa in full awareness of Reality.

Sūtra 23: This throws a flood of light on the nature of Citta and shows definitely that the word Citta is used by Patañjali in the most comprehensive sense for the medium of perception at all levels of consciousness and not merely as a medium of intellectual perception as commonly supposed. Wherever there is perception in the Relative realm of Prakṛti there must be a medium through which that perception takes place and that medium is Citta. So that even when consciousness is functioning on the highest planes of manifestation, far beyond the realm of the intellect, there is a medium through which it works, however subtle this medium may be, and this medium is also called Citta.

Sūtras 24-25: These two Sūtras point out the nature of the limitations from which life suffers even on the highest planes of manifestation. The Puruṣa is not only the ultimate source of all perception as pointed out in IV-18 but he is also the motive power or reason of this play of Vāsanās which keep the mind in incessant activity. It is for him that all this long evolutionary process is taking place although he is always hidden in the background. It follows from this that even in the exalted conditions of consciousness which the Yogi might reach in the higher stages of Yoga he is dependent upon something distinct and separate, though within him. He cannot be truly Self-sufficient and Self-illuminated until he is fully Self-realized and has become one with the Reality within himself. It is the realization of this fact, of his falling short of his ultimate objective, which weans the Yogi from the exalted illumination and bliss of the highest plane and makes him dive still deeper within himself for the Reality which is the consciousness of the Puruṣa.

Sūtras 26-29: These Sūtras give some indication of the struggle in the last stages before full Self-realization is attained. This struggle culminates ultimately in Dharma-Megha-Samādhi which opens the door to the Reality within him.

Sūtras 30-34: These Sūtras merely indicate some of the consequences of attaining Kaivalya and give a hint about the nature of the exalted condition of consciousness and freedom from limitations in which a fully Self-realized Puruṣa lives. No one, of course, who has not attained Kaivalya can really understand what this condition is actually like.

After taking a bird’s-eye view of the Section let us now deal with the different topics one by one. In the first Sūtra Patañjali gives an exhaustive list of methods whereby occult powers may be acquired. Some people are born with certain occult powers such as clairvoyance etc. The appearance of such occult powers is not quite accidental but is generally the result of having practised Yoga, in some form or another, in a previous life. All special faculties which we bring over in any life are the result of efforts which we have made in those particular directions in previous lives and Siddhis are no exception to this rule. But the fact that a person has practised Yoga and developed these powers in previous lives does not mean necessarily that he shall be born with those powers in this life. These powers have generally to be developed afresh in each successive incarnation unless the individual is very highly advanced in this line and brings over from previous lives very powerful Saṃskāras. It is also necessary to remember in this connection that some people whose moral and intellectual development is not very highly advanced are sometimes born with certain spurious occult powers. This is due to their dabbling in Yogic practices in their previous lives as explained in I-19.

Psychic powers of a low grade can often be developed by the use of certain drugs. Many Fakirs in India use certain herbs like Gānjā for developing clairvoyance of a low order. Others can bring about very remarkable chemical changes by the use of certain drugs or herbs, but those who know these secrets do not generally impart them to others. Needless to say that the powers obtained in this manner are not of much consequence and should be classed with the innumerable powers which modern Science has placed at our disposal.

The use of Mantras is an important and potent means of developing Siddhis and the Siddhis developed in this manner may be of the highest order. For, some of the Mantras like Praṇava or Gāyatrī bring about the unfoldment of consciousness and there is no limit to such unfoldment. When the higher levels of consciousness are reached as a result of such practices the powers which are inherent in those states of consciousness begin to appear naturally, though they may not be used by the devotee. Besides the natural development of Siddhis in this manner, there are specific Mantras for the attainment of particular kinds of objectives and when used with knowledge in the right manner bring about the desired results with the certainty of a scientific experiment. The Tantras are full of such Mantras for obtaining very ordinary and sometimes highly objectionable results. The reason why the ordinary man cannot get the desired results by simply following the directions in the books lies in the fact that the exact conditions are deliberately not given and can be obtained only from those who have been regularly initiated and have developed the powers. Of course, the true Yogi regards all such practices with contempt and never goes near them.

Tapas is another well-recognized means of obtaining Siddhis. The Purāṇas are full of stories of people who obtained all kinds of Siddhis by performing austerities of various kinds and thus propitiating different deities. Those stories may or may not be true but that Tapas leads to the development of certain kinds of occult powers is a fact well known to all students of Yoga. The important point to be noted in this connection is that the Siddhis acquired by this method, unless they are the result of the general unfoldment of consciousness by the practice of Yoga, are of a restricted nature and do not last for more than one life. And it frequently happens that the person who acquires such a Siddhi, being morally and spiritually undeveloped, misuses it, thus not only losing the power but bringing upon himself a lot of suffering and evil Karma.

The last and the most important means of developing Siddhis is the practice of Saṃyama. The major portion of Section III deals with some of the Siddhis that may be developed in this manner. The list of Siddhis referred to in that Section is not exhaustive but the more important ones are given. They should be taken merely as representative of an almost innumerable class to which references are found in Yogic literature.

One fact has, however, to be noted in this connection. The Siddhis which are developed as a result of the practice of Saṃyama belong to a different category and are far superior to those developed in other ways. They are the product of the natural unfoldment of consciousness in its evolution towards perfection and thus become permanent possessions of the soul, although a little effort may be needed in each new incarnation to revive them in the early stages of Yogic training. Being based upon knowledge of the higher laws of Nature operating in her subtler realms they can be exercised with complete confidence and effectiveness, much in the same way as a trained scientist can bring about extraordinary results in the field of physical Science.

Jāty-antara-pariṇāmaḥ prakṛty-āpūrāt.

into another class, species or kind

into another class, species or kind  change; transformation

change; transformation  Nature which makes, acts, creates; natural tendencies or potentialities

Nature which makes, acts, creates; natural tendencies or potentialities  by the filling up or overflow.

by the filling up or overflow.

2. The transformation from one species or kind into another is by the overflow of natural tendencies or potentialities.

The word Jāti is generally used in Saṃskṛta for class, species etc., but in the context in which it is used here it is obvious that it has to be interpreted in a much wider sense. It is only then that the profound significance of the Sūtra reveals itself and can be understood in terms of modern scientific thought.

It is difficult to grasp the underlying idea of this Sūtra from its mere translation and it will, therefore, be necessary to explain its real significance in some detail. Jāty-Antara-Pariṇāma means a transformation involving a fundamental change of nature, or substance such as genus or chemical composition and not merely a change of state or form. Thus when water is changed into ice it is merely a change of state and does not involve an essential change of substance. When a bangle made of gold is changed into a necklace, again, there is no fundamental change but merely a change of form. But when hydrogen is changed into helium, or uranium is changed into lead, it is a fundamental change of substance and comes under Jāty-Antara-Pariṇāma. Now, the Sūtra lays down that all such changes involving fundamental differences can take place only when there is present in the substance the potentiality for the change under the specified conditions. Prakṛtyāpūrāt is a beautiful and pregnant phrase for expressing a very comprehensive scientific law. Literally, it means ‘by the flow of Prakṛti’; but let us try to understand in terms of modern Science what the real significance of this phrase is. It will be best to take a few facts from our common experience to illustrate the working of this law. If we take a dry mass of wood and apply a burning match to it, the wood immediately takes fire and a whole timber yard may be reduced to ashes in a short time. But if we apply a burning match to a heap of bricks and mortar nothing happens. Why? Because, wood has in it the potentiality of combining with the oxygen of the air with the liberation of a great amount of heat and a number of volatile products and as the reaction is self-propagating involving a sort of ‘chain reaction’ a mere spark is enough to reduce the whole mass of wood to ashes. But in the case of bricks and mortar there is no potentiality to react in this manner and, therefore, when the match is applied nothing happens. Change, in such a case, therefore, takes place according to the potentialities existing in the material and follows the tendency of natural forces under the given conditions. If the conditions change, the tendencies may also change and an entirely new kind of change may be brought about. For example., the wood may be subjected to the action of certain chemical substances and converted into charcoal. Let us take another example. A breeder can evolve a new species of dog by the appropriate crossing of different kinds of dogs but he cannot produce a new species of cat in this manner. The potentiality for the production of a new species of cat does not exist in the latter case. Here again, therefore, we are bound by limitations set by natural tendencies and potentialities and cannot go against them. It is true that if we have the necessary knowledge we can, by the introduction of new factors, bring about changes which appeared impossible before, but that does not mean that we have violated the fundamental law of Nature referred to above.

Nimittam aprayojakaṃ prakṛtināṃ varaṇabhedas tu tataḥ kṣetrikavat.

incidental cause

incidental cause  non-urging; not directly causing

non-urging; not directly causing  of natural tendencies; of predisposing causes

of natural tendencies; of predisposing causes  obstacle

obstacle  piercing through; removal

piercing through; removal  verily; on the other hand

verily; on the other hand  from that

from that  like the farmer.

like the farmer.

3. The incidental cause does not move or stir up the natural tendencies into activity; it merely removes the obstacles, like a farmer (irrigating a field).

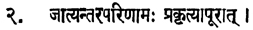

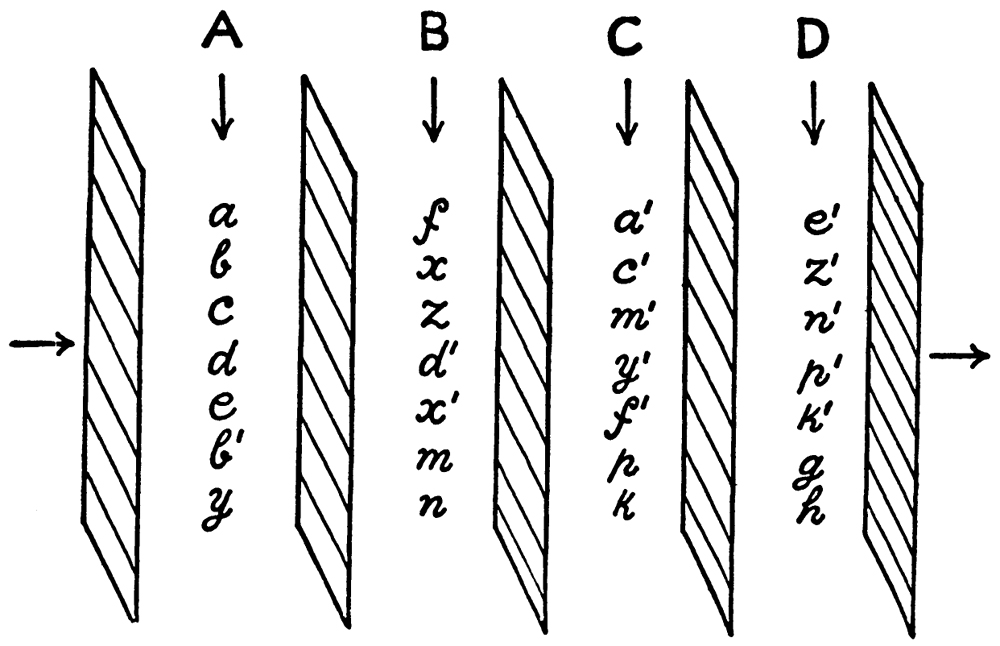

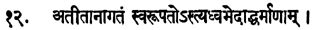

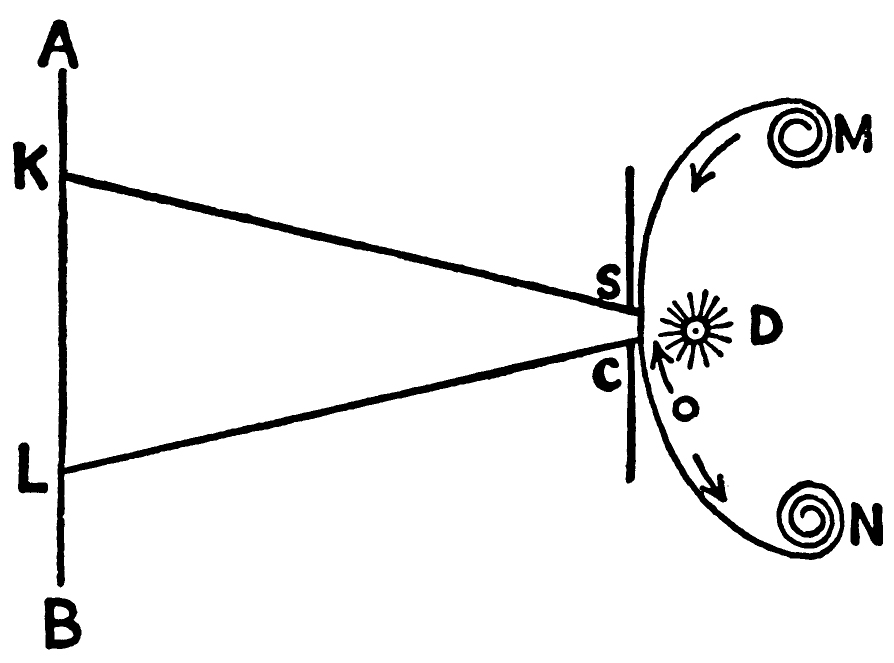

The idea embodied in IV-2 is further elaborated in IV-3. Transformation from one kind into another takes place, as we have seen, according to the resultant effect of all forces involved. Everything has the potentiality of changing in a number of directions and by bringing to bear upon it different kinds of forces, we can make it change in one or another of the directions as illustrated in the following diagram.

FIG. 11

If we have a beaker full of sugar solution we can change the sugar into alcohol by inoculating the solution with a certain kind of ferment, we can change it into a mixture of glucose and fructose by adding hydrochloric acid, we can change it into carbon by adding strong sulphuric acid and so op. All these different kinds changes can be brought about by producing different conditions, by applying different kinds of stimuli for the manifestation of different potentialities. But the potentialities for all these changes already exist in the sugar solution. We cannot, for instance, change the sugar into mercury because there is no potentiality, in the chemical sense, for sugar to change into mercury.

The incidental or existing cause which seems outwardly to bring about the change is not the real cause of the change. The change is really brought about by the predisposing causes determined by the nature of potentialities existing in the things undergoing change. What the incidental cause does is merely to determine in which direction change will take place and thus to direct the flow of natural forces in that particular direction.

The respective role of the exciting and predisposing causes in bringing about all kinds of changes in Nature is then further made clear by the use of a very apt simile “like a farmer”. Anyone who has observed a farmer directing the current of water into different parts of a field will see at once how closely such a process resembles the action of natural forces being directed by one or the other of the outward causes which seem to bring about different kinds of changes. He removes a little earth here and the water begins to flow in one furrow. Then he closes up the gap and makes a breach at another place and the water begins to flow in another direction. The removal of a little earth from one particular spot does not produce the current of water. It merely removes an obstacle in the path of the water and determines the direction of the current.

The great natural law embodied in the above two Sūtras is applicable not only to physical phenomena but to all kinds of phenomena in the realm of Prakṛti For example, the nature of our actions, good or bad, does not make our life. It merely determines the direction of our future lives. The current of our life must flow on incessantly, its direction being continually determined by our actions, thoughts and feelings.

The student may well ask: “What has this law to do with Yoga?” Everything. As has been pointed out before, the Yogi has to work out his liberation with the help of the laws which operate in the realm of Prakṛti and he, therefore, ought to have a clear idea of this fundamental law which determines the flux of phenomena taking place around him and within him. As he has to destroy completely, and for ever, certain deep-seated tendencies in his nature he ought to know their root causes which give rise to different forms of those tendencies. He ought to know that mere suppression of a tendency does not mean its removal. It will lie low in a potential form for an indefinite period and then again raise its head when suitable conditions present themselves. It is no use merely removing the exciting causes. The predisposing causes must be removed. The modem tendency is to deal only with the superficial causes and to get over the present difficulties somehow. This leads us nowhere and continually brings before us the old troubles in new and different forms.

Nirmāṇa-cittāny asmitā-mātrāt.

created; artificial

created; artificial  minds

minds  egoism; ‘I-am-ness’; sense of individuality

egoism; ‘I-am-ness’; sense of individuality  from alone.

from alone.

4. Artificially created minds (proceed) from ‘egoism’ alone.

The two previous Sūtras should prepare the ground for understanding the modus operandi of the method by which any number of additional ‘minds’ can be artificially produced by the highly advanced Yogi. Citta, as pointed out in I-2, is the universal principle which serves as a medium for all kinds of mental perceptions. But this universal principle can function only through a set of vehicles working on the different planes of the Solar system. These vehicles of consciousness, or Kośas as they are called, are formed by the appropriation and integration of matter belonging to different planes round an individual centre of consciousness and provide the necessary stimuli for mental perceptions which take place in consciousness. Patañjali has used the same word, Citta, for the universal principle which serves as a medium for mental perception as well as the individual mechanism through which such perception takes place. It is necessary to keep this distinction in mind because one or the other of the two meanings is implied by the same word—Citta—at different places.

Since the object of Section IV is partly to elucidate the nature of Citta, the question of the creation of ‘artificial minds’ has been dealt with by Patañjali in this Section. There is, of course, a ‘natural mind’, if we may use such a phrase, through which the individual works and evolves in the realms of Prakṛti during the long course of his evolutionary cycle. That mind, working through a set of vehicles, is the product of evolution, carries the impressions of all experiences through which it has passed in successive lives and lasts till Kaivalya is attained. But, during the course of the Yogic training when the Yogi has acquired the power of performing Saṃyama and manipulating the forces of the higher planes, especially Mahat-Tattva, it is possible for him to create any number of mental vehicles by duplication, vehicles which are an exact replica of the vehicle through which he normally functions. Such vehicles of consciousness are called Nirmāṇa-Cittāni and the question arises: ‘How are these “artificial minds” created by the Yogi?’ The answer to this question is given in the Sūtra under discussion.

Such artificial minds with their appropriate mechanism are created from ‘Asmitā alone’. Asmitā is, of course, the principle of individuality in man which forms, as it were, the core of the individual soul and maintains in an integrated condition all the vehicles of consciousness functioning at different levels. It is this principle, which on identification with the different vehicles, produces egoism and other related phenomena which have been dealt with thoroughly in II-6. This principle is called Mahat-Tattva in Hindu philosophy and it is through its agency that artificial minds can be created. The advanced Yogi who can control the Mahat-Tattva has the power of establishing any number of independent centres of consciousness for himself and as soon as such a centre is established an ‘artificial mind’ automatically materializes round about it. This is an exact replica of the ‘natural mind’ in which he functions normally and remains in existence as long as he wills it to be maintained. The moment the Yogi withdraws his will from the ‘artificial mind’ it disappears instantaneously.

It is worthwhile noting the significance of the word ‘alone’ in the Sūtra. The significance, of course, is that the creation of an ‘artificial mind’ does not require any other operation except that of establishing a new centre of individuality. The precipitation of an ‘artificial mind’ round about this centre is brought about automatically by the forces of Prakṛti because the capacity of gathering a ‘mind’ round itself is inherent in the Mahat-Tattva. There is nothing extraordinary or incredible in such materializations and similar phenomena take place even on the physical plane. What happens when we place a tiny seed in the ground? The seed, by the potential power which is inherent in it, immediately begins to work upon its surroundings and gradually elaborates a tree from the matter appropriated from its environment. The flow of natural forces brings about all the necessary changes needed for this development. Do we know the secret of this power? No! But still it exists and we see its action all around us in every sphere of life. What is, therefore, incredible or miraculous in a centre established in the Mahat-Tattva gathering a Citta or ‘mind’ round itself by the automatic action of natural forces (Prakṛti-Āpūrāt)? The only difference is that of time. While the tree takes considerable time to grow, the production of the ‘artificial mind’ seems to take place instantaneously. But time is a relative thing and its measure varies according to the plane upon which it functions.

The automatism which is involved in the creation of ‘artificial minds’ cannot be adequately understood unless we have a clear grasp of the natural law enunciated in IV-2-3. This, no doubt, partly accounts for the insertion of these two Sūtras before the problem of ‘artificial minds’ is dealt with by the author.

Pravṛṭṭi-bhede prayojakaṃ cittam ekam anekeṣ’m.

activity; pursuit

activity; pursuit  in the difference

in the difference  directing; moving

directing; moving  mind

mind  one

one  of many.

of many.

5. The one (natural) mind is the director or mover of the many (artificial) minds in their different activities.

If the Yogi can duplicate his ‘mind’ at different places the question arises: ‘How are the activities of these “artifical minds” thus created, co-ordinated and controlled?’ According to this Sūtra the activities and functions of the ‘artificial minds’—whatever their number—are directed and controlled by the one ‘natural mind’ of the Yogi. The ‘artificial minds’ are merely the instruments of the one ‘natural mind’ and obey it automatically. Just as the activities of the hands and other organs working in the physical body are co-ordinated by the brain and are directly under its control, in the same way the activities of the ‘artificial minds’ are co-ordinated and controlled by the Intelligence working in and through the ‘natural mind’. Of course, this Intelligence working through the ‘natural mind’ is none else but the Puruṣa whose consciousness illuminates and energizes all the vehicles. It should also be noted that the ‘artificial minds’ act not only as instruments of the ‘natural’ mind but also, as it were, the outposts of its consciousness. Pravṛtti includes both kinds of activities, those corresponding to Jñānendriyas and Karmendriyas, the receptive and operative functions of consciousness.

Tatra dhyānajam anāśayam.

of them

of them  born of meditation

born of meditation  free from Saṃskāras or impressions; germless.

free from Saṃskāras or impressions; germless.

6. Of these the mind born of meditation is free from impressions.

To all outer appearances the ‘artificial minds’ are exact replicas of the ‘natural mind’ but they differ from it in one fundamental respect. They do not carry with them any impressions, Saṃskāras or Karmas which are an integral part of the ‘natural mind’. The ‘natural mind’ is the product of evolutionary growth and is the repository of the Saṃskāras of all the experiences which it has passed through during the course of successive lives. These Saṃskāras in their totality are referred to as Karmāśaya ‘vehicle of Karmas’ and have been dealt with in II-12. The ‘artificial minds’ created by the will-power of the Yogi are free from these impressions and one can easily see why this should be so. They are merely temporary creations which disappear as soon as the work for which they are created is finished. A business firm may be obliged to open a temporary branch in some locality for a particular purpose. Although business is transacted at the office of the new branch all accounts etc. are kept at the head office. The temporary office is merely an outpost of the head office and has really no independent status. The assets and liabilities belong to the head office. A somewhat similar relationship exists between the ‘artificial minds’ and the one ‘natural mind’.

Karmāśuklākṛṣnaṃ yoginas tri-vidham itareṣām.

action

action  not white

not white  not black

not black  of a Yogi

of a Yogi  fasten threefold

fasten threefold  of others.

of others.

7. Karmas are neither white nor black (neither good nor bad) in the case of Yogis, they are of three kinds in the case of others.

The next topic which Patañjali takes up is the question of gaining freedom from the bondage of Karma which is a sine qua non for the attainment of Kaivalya. The subject of Karma has already been dealt with in II-12-14 and is taken up again here. In Section II the problem was discussed from a different angle—in relation to Kleśas—and it was shown how the Kleśas are the underlying cause of Karmas which in their turn produce pleasant or unpleasant conditions in this or future lives according as they are good or bad. But here, in Section IV, the subject has been taken up again and is dealt with from an entirely different point of view—with the object of showing how the Yogi may get rid of the Karmāśaya—the vehicle of Karma—which contains the accumulated Saṃsakāras of all the previous lives and which binds the soul to the wheel of birth and death. Unless and until all these Saṃskāras are destroyed or rendered inoperative no freedom from the bondage of Prakṛti is possible even though the Yogi may have reached an advanced state of illumination. The force of his Saṃskāras will pull him back again and again and prevent him from reaching the ultimate goal.

IV-7 gives a classification of Karma as well as indicates the means of avoiding the formation of new Karma. Karmas are neither black nor white in the case of those who are Yogis, they are of three kinds in the case of ordinary people. Black and white obviously describe the two kinds of Karmas which produce painful and pleasurable fruits referred to in II-14. The third kind of Karmas are those which are of mixed character. For example, many actions which we do have different effects upon different people. They benefit some and harm others and consequently produce Karmas of mixed character.

The word Yogi in this Sūtra means not only one who is practising Yoga but also one who has learnt the technique of Niṣkāma Karma. He does all his actions in a state of at-one-ment with Iśvara and does not, therefore, produce any personal Karma. The theory of Niṣkāma Karma is an integral part of Hindu philosophical thought and is well known to all students of Yoga. It is not, therefore, necessary to discuss it here in detail, but the broad central idea underlying it may be given. According to this doctrine personal Karma results from the performance of an ordinary action because the guiding force or motive of the action is personal desire—Kāma. We do our actions identifying ourselves with our ego who sees the fulfilment of his own desires and naturally reaps the fruits in the form of pleasurable and painful experiences. When an individual can dissociate himself completely from his ego and performs action in complete identification with the Supreme Spirit which is working through his ego, such an action is called Niṣkāma (without desire). It does not naturally produce any personal Karma and consequently does not bring any fruit to the individual.

It is necessary to note, however, that it is conscious and effective dissociation from the ego which neutralizes the operation of the law of Karma and not a mere thought or intention or wish on the part of the individual. So real Niṣkāma Karma is possible only to highly advanced Yogis who have risen above the plane of desires. Many well-meaning people trying to lead the religious life imagine that merely by wishing to be desireless or thinking of dissociating themselves from their ego, superficially dedicating their actions to God, will free them from the binding action of Karma. This is a mistake though it is true that persistent efforts of this kind will naturally pave the way for acquiring the right technique. As well may a person hope to free himself from the law of gravitation by thinking of rising in the air. What is needed, as has been pointed out above, is a real, conscious identification with the Divine within us and freedom from any taint of personal motive. To the extent that the action is so tainted will it produce Kārmic effect with its binding power over the individual.

When the technique of Niṣkāma Karma has been learnt and applied to all actions, no personal Karma is incurred by the Yogi even though he may be busily engaged in the affairs of the world as an agent of the Divine Life within him. All his Karmas are ‘consumed in the fire of Wisdom’ in the words of the Bhagavad-Gitā. But what about the Karmas that he has already accumulated in his present and past lives? He ceases to add any new Saṃskāras to the accumulated stock, but an enormous number of Saṃskāras are already there in his Karmāśaya which must be exhausted before Liberation is attained. He cannot, simply by willing, make these Saṃskāras disappear. He must wait patiently till they have been completely exhausted and he has paid up the last pie of his debt. It is, therefore, natural that the exhaustion of his Karmas which bind him to other souls should be a long drawn-out process extending probably over many lives. It is true that he has been paying heavy instalments of his Kārmic debts since he has taken to the path of Yoga. It is also true that as he advances on the path of Yoga and is able to function on the higher planes new powers come to him which enable him to expedite this process. For example, he can make ‘artificial minds’ and ‘artificial bodies’ (Nirmāṇakāyās) and through them pay off simultaneously his debts to people who are scattered far and wide in time and space. Still, with these new powers and facilities for hastening the Kārmic process at his disposal he is bound by the laws of Prakṛti and has to work within the framework of these laws. And this naturally requires time and wise and careful adaptation of means to ends.

Tatas tad-vipākānuguṇānām evābhi-vyaktir vāsanānām.

thence

thence  their ripening; fruition

their ripening; fruition  accordant; correspondent; favourable

accordant; correspondent; favourable  only

only  manifestation

manifestation  of potential desires; of tendencies.

of potential desires; of tendencies.

8. From these only those tendencies are manifested for which the conditions are favourable.

What has been said above about the nature of Niṣkāma Karma must have brought home to the student that it is desire or personal attachment which is the motive power of action in the case of ordinary people and which produces the Saṃskāras both in the form of tendencies and potentialities as well as Karmas which bring pleasant or painful experiences.

The forces set in motion by our thoughts, desires and actions are of a complex nature and produce all kinds of effects which it is difficult to classify completely. But all these leave some kind of Saṃskāra or impression which binds us in one way or another for the future. Thus our desires produce potential energy which draws us irresistibly to the environment or conditions in which they can be satisfied. Actions produce tendencies which make it easier for us to repeat similar actions in future and if they are repeated a sufficient number of times may form fixed habits. In addition, if our actions affect other people in some way they bind us to those people by Kārmic ties and bring pleasant or unpleasant experiences to ourselves. Our thoughts also produce Saṃskāras and result in desires and actions in accordance with their nature.

If, however, we analyse these different kinds of mental and physical activities we shall find that at their base there are always desires of one kind or another which drive the mind and result in these thoughts and actions. Desire in its most comprehensive sense is thus a more fundamental factor in our life than our thoughts and actions because it is the hidden power which drives the mind and body in all kinds of ways for the satisfaction of its own purposes. The mind is thus mostly an instrument of desires and its incessant activity results from the continuous pressure of these desires upon it. Of course, ‘desire’ is not an apt word for the subtle power which drives the mind at its higher levels and which binds consciousness to the glorious realities of the spiritual planes. The word used in Saṃskṛta for this power which works at all levels of the mind is Vāsanā. Just as Citta is the universal medium for the expression of the mind principle, so Vāsanā is the universal power which drives the mind and produces the continuous series of its transformations which imprison consciousness. In fact, the word Vāsanā used in the present context is of a still more comprehensive significance, for it not only indicates the principle of desire in its widest sense but also the tendencies and Karmas which this principle generates on the different planes. For desire and the Karmas or tendencies which it produces form a vicious circle in which causes and effects are inter wined and it is difficult to separate them. So the use of the word Vāsanā for both is quite justifiable.

Since different types of Vāsanās require differerent kinds of conditions and environment for their manifestation, it is quite obvious that they cannot find expression in any haphazard manner but must follow a certain sequence determined by the different types of environments and conditions through which the individual passes in the successive incarnations. And this is what IV-8 points out. If a person has a strong desire for being a champion athlete when he has inherited a weak and diseased body his desire cannot naturally be fulfilled in that life. If an individual A has strong Kārmic ties with another individual B who is not in incarnation at the time and those ties require physical expression they will naturally remain in abeyance for the time being and can be worked out only when both are present in physical incarnation at the same time. It will be seen, therefore, that only a limited number of Vāsanās, whether in the form of desire or Karmas, can find expression in a particular incarnation, firstly, because the span of human life is more or less limited, and secondly, because the conditions for the expression of different kinds of Vāsanās are frequently incompatible. That portion of the accumulated stock of Vāsanās (Sancita Karma) which can find expression and is ready to be precipitated in one particular incarnation is known as Prārabdha Karma of the individual. The life of an ordinary individual is confined within the framework thus made for him and his freedom to alter its main trends is extremely limited. But a man of exceptionally strong will, and especially a Yogi whose knowledge and powers are extraordinary, can make considerable changes in the plan of life thus marked out for him. In fact, the more the Yogi advances on the path of Yoga which he is treading the greater is his hand in determining the pattern of his lives, and when he is on the threshold of Kaivalya he is practically the master of his destiny.

In spite of the comprehensive sense in which the word Vāsanā is used it should be noted that emphasis in this Sūtra is on that aspect of Vāsanā which is expressed in the form of tendencies of which Karmas are merely secondary effects.

Jāti-deśa-kāla-vyavahitānām apy ānantar-yaṃ smṛti-saṃskārayor ekarūpatvāt.

(by) class

(by) class  (by) locality

(by) locality  (by) time

(by) time  separated; divided

separated; divided  even

even  sequence; non-interruption; immediate succession

sequence; non-interruption; immediate succession  of memory and impressions

of memory and impressions  because of the sameness in appearance or form.

because of the sameness in appearance or form.

9. There is the relation of cause and effect even though separated by class, locality and time because memory and impressions are the same in form.

The seemingly irrauonai and disjointed manner in which Vāsanās have to work out in the successive incarnations may give rise to a philosophical difficulty in the mind of the student and Patañjali proceeds to remove this difficulty in this Sūtra. It happens very frequently that one personality of an individual does some particular action but because the Karma of that action cannot be worked out by that personality owing to the absence of the necessary conditions, it has to be worked out by another personality of the same individual in a later life. And this second personality has no memory of the particular action for which it is undergoing that experience. Of course, if this experience is pleasurable no question arises in the mind of the second personality as to the justice of the undeserved good luck. But if the experience is painful there is felt a grievance against Fate for the undeserved pain or suffering. A tremendous amount of this kind of resentment against ‘undeserved’ suffering poisons the minds of people who are ignorant of the Law of Karma and its mode of working and a wider understanding of this Law will do much to make people see things in their true light and to take the experiences of life as they come with patience and without bitterness.

Coming back to the philsophical difficulty we may ask: ‘Why should the second personality in the later life suffer for the wrongs done by the first personality in the previous life, and if it has to, how can the law of Karma be called just?’ The answer to this question is given in the Sūtra we are dealing with. Of course, in expounding a philosophical system or scientific technique in the Sūtra form much is left to the intelligence of the student who is supposed to be familiar with the general doctrines upon which the philosophy or science is based. Only the essential ideas which form, as it were, the steel frame of the mental structure are given and even these are stated as conscisely as possible. The doctrine of reincarnation which is an integral part of Yogic philosophy and which is taken for granted by Patañjali implies that the chain of personalities in the successive incarnations are temporary expressions of a higher and more permanent entity who is called by different names in different schools of thought such as the Jivātmā or the Immortal Ego or the individuality. It is this Jivātmā who really incarnates in the different personalities and the latter may be considered to be more or less outposts of his consciousness in the lower worlds during the period of the incarnations.

Now, the important point to note here is that the over-all memory embracing all the successive lives resides in the ‘mind’ of the Jivātmā and the different personalities which succeed one another do not share the over-all continuous memory. Their memory is confined only to the particular experiences gone through by them in each separate incarnation. This continuous memory embracing the chain of lives is due to the fact that the Saṃskāras of all the experiences gone through in these lives are present in the permanent higher vehicles of the Jivātmā. Just as the contact of the needle with the impressions on the gramophone record reproduces sound, just as the contact of the mind with the physical brain reproduces memory of experiences gone through in this life, in the same way, the contact of the higher consciousness with the Saṃskāras or impressions in the higher vehicles of the Jivātmā reproduces memories corresponding to the Saṃskāras contacted. The vehicle which is the repository of all these Saṃskāras is called ‘Kāraṇa Śarīra’ in Vedāntic terminology because it is the repository of all the germs of future experiences.

It will be seen from what has been said above how the experiences and the corresponding memories of the different personalities scattered in different conditions of class, time and space are integrated in the consciousness of the Jivātmā who has passed through all the experiences and is the real sower and reaper of the Karmas accruing from them. Seen in this light, reaping the bitter fruits by a personality for the wrongs done by another personality which has gone before does not involve any injustice because the different personalities are expressions, under different conditions, of the same entity though they may not be aware of the fact in their physical consciousness, A particular personality (Jiva) is not aware of the whole series of experiences and Saṃskāras but the Jivātmā is, and in the long uninterrupted series of actions and reactions sees the natural working out of the law of Karma and no favouritism or injustice whatsoever. We do not grumble when we find that the unpleasant experiences which we have to go through are the direct result of our own folly or wrong doing. And neither does the Jivātmā before whose vision all the past lives lie like an open book.

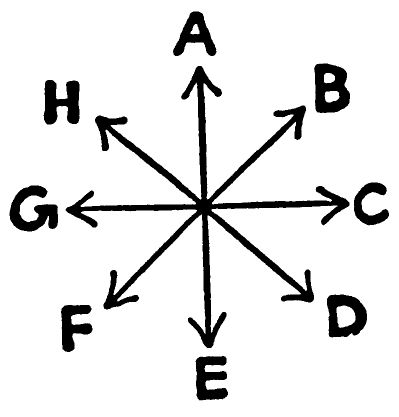

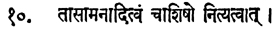

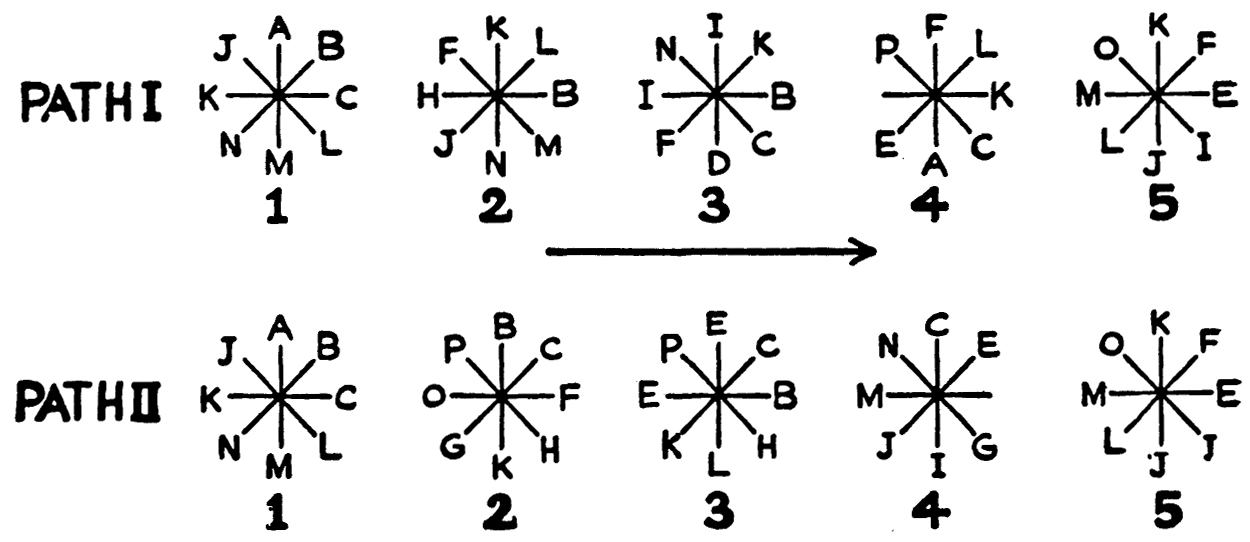

The manner in which the over-all memory of the Jivātmā enables him to see the perfect working out of causes are effects even though they are scattered over different lives in an irregular manner can be illustrated by a simple diagram given below:

FIG. 12

a, b, c, d, etc. represent the different causes set going by a particular Jivātmā in four lives represented by compartments A, B, C and D and a’ b’ c’ d’, etc. the corresponding Kārmic effects which ensue in the same or a subsequent life. If these letters are distributed in the four separate compartments in an irregular manner only keeping in mind that each effect follows its corresponding cause then it will not be possible for anyone whose vision is confined to only one compartment to correlate all the causes and the effects which are precipitated when the appropriate conditions present themselves either in the same life or in subsequent lives. But if anyone looks at the letters from a distance so that all the letters in the different compartments are visible simultaneously then every effect can be traced to its corresponding cause, and in spite of the irregular mixing up of the causes and effects in the different compartments, the law of cause and effect is seen to be strictly obeyed.

Tāsām anāditvaṃ cāśiṣo nityatvāt.

of them

of them  no beginning

no beginning  and; also

and; also  of the (current of) desire or will to live

of the (current of) desire or will to live  because of the eternity or permanence.

because of the eternity or permanence.

10. And there is no beginning of them, the desire to live being eternal.

We have seen in the previous Sūtra that human life is a continuous series of experiences brought about by setting in motion certain causes which are followed sooner or later by their corresponding effects, the whole process thus being an uninterrupted play of actions and reactions. The question naturally arises: ‘When and how does this process of accumulating Saṃskāras begin and how can it be ended?’ We are bound to the wheel of births and deaths on account of Vāsanās which result in experiences of various kinds and these in their turn generate more Vāsanās. We seem to be facing one of those philosophical riddles which seem to defy solution. The answer given by Patañjali to the first part of the question posed above is that this process of accumulating Saṃskāras cannot be traced to its source because the ‘will to live’ or the ‘desire to be’ does not come into play with the birth of the human soul but is characteristic of all forms of life through which consciousness has evolved in reaching the human stage. In fact, the moment consciousness comes into contact with matter with the birth of Avidyā and the Kleśas begin to work, Saṃskāras begin to form. Attractions and repulsions of various degrees and kinds are present even in the earliest stages of evolution—mineral, vegetable and animal—and an individual who attains the human stage after passing through all the previous stages brings with him all the Saṃskāras of the stages through which he has passed, though most of these Saṃskāras lie dormant in a latent condition. Animal traits are recognized even by Western psychology as present in our sub-conscious mind, and the occasional emergence of these traits belonging to the lower stages is due to the presence within us of all the Saṃskāras which we have gathered in our evolutionary development. That is why, as soon as the control of the Higher Self temporarily disappears or slackens owing to heightened emotional disturbances or other causes, human beings begin to behave like beasts or even worse than beasts. That, incidentally, shows the necessity of keeping a rigid control over our mind and emotions because once this is completely lost there is no knowing what undesirable Saṃskāras which have been lying dormant through the ages may become active and make us do things for which we may have to repent afterwards. History provides many instances of the recrudescence of such traits in human beings and the temporary reversion to the animal stage. It is true that the human, animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms are clearly defined and are separate stages of evolution and there can be no retrogression, from one kingdom to another, but as far as Saṃskāras are concerned they may be considered to be continuous and the human stage may be considered as the summation and culmination of the previous stages.

As evolution progresses, Vāsanās become more and more complicated and in the human stage assume a bewildering variety and complexity owing to the introduction of the mental element. The intellect, though it is the servant and instrument of desire to a certain extent, plays in its turn an important part in the growth of the desire nature and the highly complicated and various desires of the modern civilized man bear an interesting contrast to the comparatively simple and natural desires of the primitive man. As evolution progresses still further and with the practice of Yoga subtler levels of consciousness are contacted, desires become more and more refined and subtle and thus more difficult to detect and transcend. But even the subtlest and most refined desire which binds consciousness to the bliss and knowledge of the highest spiritual planes differs only in degree and is really a refined form of the primary desire—‘will to live’ which is called Āśiṣaḥ. It will be seen that it is not possible to destroy Vāsanās and thus put an end to the life process by tackling them on their own plane. Even Niṣkāma Karma when practised perfectly can only stop generating new personal Karma for the future. It cannot destroy the root of Vāsanā which is inherent in manifested life. As Viveka and Vairāgya develop, the active Vāsanās become more and more quiescent but their Saṃskāras remain and like seeds can burst forth into active form whenever favourable conditions present themselves and appropriate stimuli are applied to the mind.

Hetu-phalāśrayālambanaiḥ saṃgṛhitatvād eṣām abhāve tad-abhāvaḥ.

(with) cause

(with) cause  effect

effect  substratum; that which gives support

substratum; that which gives support  object

object  because of being bound together

because of being bound together  of these

of these  on the disappearance

on the disappearance  disappearance of them.

disappearance of them.

11. Being bound together as cause-effect, substratum-object, they (effects, i.e. Vāsanās) disappear on their (cause, i.e. Avidyā) disappearance.

If the Vāsanās form a continuous stream and no release from bondage is possible without their destruction how can Liberation be attained? The answer to this question was given in the theory of Kleśas which has been dealt with already in Section II. We saw that the cyclic progress of manifested life for the Puruṣa begins with the association of his consciousness with Prakṛti through the direct agency of Avidyā. Avidyā leads successively to Asmitā, Rāga-Dveṣa and Abhiniveśa and all the miseries of life in bondage.

If Avidyā is the ultimate cause of bondage and the whole process of the continuous generation of Vāsanās rests on this basis it follows logically that the only effective means of attaining freedom from bondage is to destroy Avidyā. All other means of ending the miseries and illusions of life which do not completely destroy Avidyā can, at best, be palliatives and cannot lead to the goal of Yogic endeavour—Kaivalya. How this Avidyā can be destroyed has been discussed very thoroughly and systematically in Section II and it is not necessary to deal with this question here.

Atītānāgataṃ svarūpato ’sty adhva-bhedād dharmāṇām.

the past

the past  the future

the future  in reality; in its own form

in reality; in its own form  exists

exists  because of the difference of paths

because of the difference of paths  of properties.

of properties.

12. The past and the future exist in their own (real) form. The difference of Dhartnas or properties is on account of the difference of paths.

This is one of the most important and interesting Sūtras in Section IV because it throws light on a fundamental problem of philosophy. That there is a Reality underlying the phenomenal world in which we live our life is taken for granted in all schools of Yoga, the aim of Yoga, in feet, being the search for and discovery of this Reality. The question arises: ‘Is this world of Reality absolutely independent of the phenomenal world in time and space which we contact with our mind or are the two worlds related to each other in some way?’ According to the Great Teachers who have found the Truth the two worlds are related though it is difficult for the intellect to comprehend this relationship. If there is a relation existing between the two worlds we may further enquire whether the manifested worlds in time and space rigidly express a predetermined pattern of Divine Thought, just as a picture on a cinema screen is the result of a mechanical projection of the photographs in the film roll. Or does the procession of events in the phenomenal world merely conform to a Plan which exists in the Divine Mind in the same way as the construction of a building follows the plan of the architect? The first view will imply Determinism in its most rigid form while the second will leave some room for Free Will.

The Sūtra under discussion throws some light on this philosophical problem. It is composed of two separate parts, the second part amplifying the first. The statement ‘the past and future exist in their own form’ means obviously that the succession of phenomena which constitute the world process or any part of it is the expression, in terms of time, of some reality which exists in the subtler realms of consciousness beyond the range of the human intellect. This reality transcends time and yet expresses itself as time in the world process.

As this question of time will be dealt with thoroughly in connection with IV-33 let us pass on and proceed to consider the second part of the Sūtra with which we are immediately concerned at this stage. ‘The difference of Dharmas is on account of the difference of paths.’ This is apparently an abstruse statement which does not seem to make sense and the existing commentaries do not throw any light on it. Let us see whether it is not possible to get at the meaning of the author in the light of what has been said with regard to the nature of the past and future in the first part of the Sūtra.

If the succession of phenomena which we cognize with our mind is the expression of some reality and if this expression is not a mere mechanical projection implying Determinism in its rigid form then it follows logically that the fulfilment of this reality in terms of time and space must be possible along a number of paths any one of which may be actually followed as a result of all the forces working in the realm of Nature. The series of events which have taken place already and become the ‘past’ represent the path trodden by the Chariot of Time so far and have become fixed—part of the memory of Nature in the Ākāśic records. What about the events which are still in the womb of the ‘future’? What shape are the events going to take in becoming the ‘past’ in their turn? As these events will not be the result of the working out of a rigid inexorable destiny but elastic adaptations to a Divine Pattern the path which they take must be at least to some extent indeterminate. There must be a certain amount of latitude for movement if there is freedom of choice and free will has any place in the scheme of things. Of course, there are forces working in the field which, to a certain extent, will determine the direction in which events will move; There is, for example, the pressure of evolutionary forces. There is the directing force of the Divine Plan and archetypes in every sphere of development. There is the tremendous pressure of the potential power of the Saṃskāras both in the realm of matter and mind. But within the limitations set by these different forces tending to mould the future there is, still, a certain freedom of movement which makes it possible for the future to develop along one of the many possible lines which open out from moment to moment. It is in this way, therefore, that in the world of the Relative, influenced by the Divine Pattern on the one hand and the momentum of the past on the other events move forward towards their final consummation.

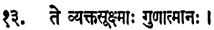

Having understood the significance of the phrase ‘difference of paths’ let us now see how these different paths merely represent the emergence of different properties in the substratum, i.e. Prakṛti. The path taken by the course of events, if we analyse it carefully, is nothing else than a particular series of phenomena in a particular order, each element of this series, in its turn, being nothing more than a particular combination of properties or Dharmas which are all inherent in Prakṛti. If we represent, for the sake of illustration, these different properties by A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, etc.

FIG. 13

then different courses of events may be represented by different series of phenomena in the following manner:

FIG. 14

It will be noted that each element of this phenomenon is nothing but a particular combination of Dharmas which have become manifest at a particular moment of time. It does not matter whether we consider the phenomena within a limited sphere like our Solar system or within the unlimited sphere of the Universe for they all take place within the realm of Prakṛti It is thus possible, beginning with a particular situation, to arrive at another situation by two or more alternative paths.

These paths followed by the course of events in the phenomenal world are not of purely mechanical origin, as the materialists would have us believe. They, in some mysterious way, bring about the fulfilment of the Eternal as has been pointed out above. The lower phenomenal world does not exist for its own sake (being merely a law of mechanical necessity) but for the sake of fulfilling the Eternal. Its object is to bring about certain ‘changes’ in the higher spiritual worlds, these ‘changes’ being the very object of its existence. The use of the word ‘changes’ in connection with the Eternal is no doubt extremely incongruous but the student should understand that it is employed, for lack of a better term, to indicate that subtle and mysterious reaction which our life in the phenomenal world has on our eternal being. A specific instance will perhaps make the point clear. The unfoldment of the perfection which is latent in every human soul is the object of the reincarnations in the lower worlds through which it is made to pass. The different kinds of experiences through which the soul passes, life after life, stimulate gradually its spiritual nature and unfold the perfection which finds its consummation in Kaivalya. Now, the type and number of these experiences do not really matter as long as the objective is reached. A particular individual may go through a hundred lives of the most intense and painful experiences or he may take one thousand lives containing experiences of an entirely different nature to attain perfection. The path does not matter, it is the attainment of the goal which is important. The path lies in the world of phenomena which is unreal and illusory while the objective lies in the world of the Eternal which is Real.

It is this possibility of taking different paths that enables the Yogi to cut short the process of unfoldment in the phenomenal worlds and to attain perfection in the shortest possible time. He is not bound to go along the long and easy road of evolution which humanity as a whole is treading. He can step out of this broad road and take the short and difficult climb to the mountain top by following the path of Yoga. But if he is bent on breaking through the world of phenomena into the world of Reality he must first understand the nature of these phenomena and the manner in which they are perceived by the mind. That is why Patañjali has dealt with this question in IV-12.

Te vyakta-sūkṣmāḥ guṇātmānaḥ.

they

they  manifest

manifest  subtle; unmanifest

subtle; unmanifest  of the nature of Guṇas.

of the nature of Guṇas.

13. They, whether manifest or unmanifest, are of the nature of Guṇas.

In the last Sūtra it was pointed out that all kinds of phenomena which are the object of perception by the mind are nothing but different combinations of Dharmas or properties which are inherent in Prakṛti. In this Sūtra the idea is carried one step further and it is pointed out that the Dharmas themselves are nothing but different combinations of the three primary Guṇas. This is a sweeping statement which is likely to startle anyone who is not familiar with the theory of Guṇas but to one who understands this theory it will appear as a perfectly logical conclusion which flows naturally from that theory. If the three Guṇas are the three fundamental principles of motion (inertia, mobility, vibration) and if motion of some kind or another lies at the basis of manifestation of all kinds of properties then these properties must be of the nature of Guṇas. Physical, chemical and other kinds of properties which modern Science has studied so far can be traced ultimately to motions and positions of different kinds and so the theory that properties are of the nature of Guṇas is in accord with the latest scientific developments as far as they go. But the statement in the Sūtra under discussion is of an all-embracing character and comprises not only physical properties which we can cognize with our physical senses but also subtle properties pertaining to the subtler worlds. Thoughts, emotions and in fact all kinds of phenomena involving Dharmas come within its scope. The word Sūkśma means not only properties related to the subtler planes but also those which are unmanifest or dormant. The only difference between manifest and dormant properties is that while the manifest properties are the result of particular combinations of Guṇas in action the dormant properties are those which exist potentially in Prakṛti in the form of theoretical combinations of Guṇas not yet materialized. Thousands of new compounds are being produced in the field of chemistry every year. Each of these represents a new combination of Guṇas which was latent so far and has only now become manifest. Prakṛti is like an organ having the potentiality for producing an innumerable number of notes. The manifest qualities are the notes which are struck and give their specific sound, the unmanifest qualities are the notes which are silent, lying in repose. But they are all there to emerge at any moment and play their part in the phenomena which are taking place everywhere, all the time.

The importance of the generalization contained in this Sūtra thus lies not only in the fact that it goes to the very bedrock in revealing the true nature of all kinds of phenomena but also in its extraordinary comprehensiveness. No generalization of modern Science can perhaps compare in its all-embracing nature with this doctrine of Yogic philosophy and as it is based upon a vision of the worlds of phenomena from the vantage-ground of Reality there is no doubt that the more Science advances into the realms of the unknown the more it will corroborate the Yogic doctrine.

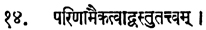

Pariṇāmaikatvād vastu-tattvam.

transformation; change

transformation; change  on account of the uniqueness

on account of the uniqueness  of the object

of the object  the essence; reality.

the essence; reality.

14. The essence of the object consists in the uniqueness of transformation (of the Guṇas).

What is the essential nature of any object or thing which is an object of mental perception? We can know of the existence and nature of anything only from the properties which it has at a particular moment. There is no other way. This ‘bundle of properties’ which in their totality constitute the thing must therefore be a unique combination of the three Guṇas since each property taken by itself is nothing more than a peculiar combination of the Guṇas. Anyone with some knowledge of modem Science can take up any physical object and break it up into its physical and chemical components—into molecules, atoms, electrons, etc. and these ultimately resolve into different kinds of forces and motions. Nothing material in the usual sense is left over if we take into consideration the fact that matter and energy are interconvertible. As far as we can see, it is all a play of different kinds of forces and motions of extraordinary variety and complexity. It is true we do not yet know exactly the nature of the nucleus of the atoms but from the trend of researches in this field it is very probable that this also will be found to be nothing more than a combination of different kinds of motions. So that, as far as it goes, modern Science corroborates the truth of the Yogic doctrine that every object which we perceive with our mind is merely a unique transformation of the three Guṇas. It should be noted that the clue to the meaning of the Sūtra lies in the word Ekatvāt which does not mean here ‘oneness’ but ‘uniqueness’. Interpreted in this way the Sūtra fits in perfectly in the chain of reasoning adopted by Patañjali to explain the theory of mental perception.

Vastu-sāmye citta-bhedāt tayor vibhaktaḥ panthāḥ.

object being the same

object being the same  because of there being difference of the mind

because of there being difference of the mind  of these two

of these two  separate

separate  path; way of being.

path; way of being.

15. The object being the same the difference in the two (the object and its cognition) is due to their (of the minds’) separate paths.

If each object is a unique transformation of the three Guṇas and has thus a definite identity of its own why then does it appear different to different minds? It is a matter of common experience that no two minds see the same thing alike. There is always a difference in cognition though the thing is the same. The reason for this difference, as pointed out in this Sūtra, lies in the fact that the minds which cognize the thing are in different conditions and thus naturally get different impressions from the same object. When one vibrating body strikes another vibrating body the result of the impact depends upon the condition of both the bodies at the time of the impact. The mental body which comes in contact with the object of perception is not a passive or static thing. It is vibrating in all sorts of ways and, therefore, must modify every impression received by its own rate of vibration. It is, therefore, not possible to obtain a true impression of the object as long as the mind itself is not free from its Vṛttis. The impression created will depend upon the condition of the receiving mind and as all minds are in different conditions, because they have followed different paths in their evolution, they must get different impressions from the same object. The student should keep in mind the distinction between the mental body which vibrates and the mind in which the Vṛttis are produced by these vibrations.

Is it possible to get a true impression of an object under any circumstances? Yes, when the mind has been freed from its Vṛttis and does not, in consequence, modify the impression made upon it by the object. When the Vṛttis have been eliminated the mind becomes one with the object (I-41), which is another way of saying that it receives an exact impression of the object without its own modifying influence. So it is only in Samādhi, when all the Vṛttis have been suppressed, that it is possible to know the object as it really is.

Even in our everyday life we find that the more a mind is influenced by different biases, prejudices and other disturbances the greater is the distortion produced in the impressions which are made upon it by men and things. A calm and dispassionate mind can alone see things correctly as far as this is possible under the limitations of ordinary life.

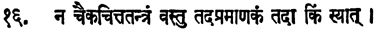

Na caika-citta-tantraṃ vastu tad-apramā-ṇakaṃ tadā kiṃ syāt.

not

not  and

and  one

one  mind

mind  dependent on

dependent on  object

object  that

that  non-cognized; unwitnessed

non-cognized; unwitnessed  then

then  what

what  would be; would happen to.

would be; would happen to.

16. Nor is an object dependent on one mind. What would become of it when not cognized by that mind?

If each object of mental perception is a mere bundle of properties which produce different impressions upon different minds, then, mental perception may be considered as a purely subjective phenomenon and it may be argued that the object need not have an independent existence apart from the cognizing agent, i.e., the mind. This purely idealistic theory of philosophy is disposed of by the objection raised in this Sūtra. If the object of mental perception is only a product of the mind which perceives it and has no independent existence of its own, then, what becomes of the object when the mind ceases to perceive it? If we accept the purely idealistic theory that objects in the external world have no real existence of their own but are mere creations of the mind then we are led to the absurd conclusion that the external world appears and disappears with the appearance and disappearance of objects in the mind of each individual, and it becomes difficult to account for the uniformity of experiences of different people with regard to different things and the harmonious co-ordination of observations made by different individuals.

No useful purpose will be served by going further into the implications of this theory. It is enough to note that Patañjali does not accept it. The Yogic philosophy recognizes the existence of ‘objects’ outside the mind. It is these objects which stimulate the mind in particular ways and produce impressions which are then perceived by the Puruṣa. It is true that the objects which produce the impressions are considered to be mere combinations of Guṇas. It is also true that the mind perceives not the objects themselves but the impressions made by them upon it. But still, there is something external to the mind which stimulates the mind to form images whatever its nature may be. It will be seen, therefore, that the theory of mental perception upon which the Yogic philosophy is based steers a middle course between pure idealism and pure realism and reconciles in a harmonious conception the essential features of both. The main postulates of the theory are given in the next few Sūtras.

Tad-uparāgāpekṣitvāc cittasya vastu jñātājñātam.

the colouring thereby

the colouring thereby  because of needing

because of needing  for the mind; by the mind

for the mind; by the mind  an object

an object  known

known  unknown.

unknown.

17. In consequence of the mind being coloured or not coloured by it, an object is known or unknown.

The first essential for the mind of an individual ‘knowing’ an object is that the object should affect or modify the mind in some way. The phrase actually used is ‘colouring the mind’. The use of the word ‘colouring’ for ‘modifying’ is not merely a poetic way of stating a scientific fact. It is used with a definite purpose in view. The word ‘modification’ would merely imply a partial change in the mind while the idea which has to be conveyed is a change which may vary in intensity from a mere trace to a depth of any intensity. The knowledge of the object may be extremely superficial or very deep and all these progressively increasing degrees of understanding can best be conveyed by using the word ‘colouring’, the depth of the colour indicating the degree of assimilation of the object by the mind. Besides, it is only by the use of the word ‘colouring’ that the complete fusion of the object and the mind referred to in Sūtra I-41 can be properly understood.

Those who have ever tried to study a subject which is entirely new to them and much beyond their mental capacity will be able to form some idea regarding the necessity of an object ‘colouring’ the mind before it can be understood. The subject is not assimilated by the mind at all, simply refuses to sink into the mind as a dye sometimes refuses to stain a tissue. The mind must ‘take in’ the object to a certain extent at least if it is to ‘know’ it and the extent to which it assimilates the object determines the degree of knowledge. This ‘colouring’ of the mind by an external object is found on deeper analysis to be nothing more than the capacity of the mental vehicle to vibrate in response to the stimulus provided by the object. The more fully the vehicle can vibrate in this manner the greater is the knowledge of the object which the mind acquires. Herein comes the necessity of evolution of the vehicles in the earlier stages.

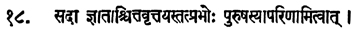

Sadā jñātāś citta-vṛttayas tat-prabhoḥ puruṣasyāpariṇāmitvāt.

always

always  (are) known

(are) known  the modifications of the mind

the modifications of the mind  of its lord

of its lord  of the Puruṣa

of the Puruṣa  on account of the changelessness or constancy.

on account of the changelessness or constancy.

18. The modifications of the mind are always known to its lord on account of the changelessness of the Puruṣa.

As soon as an object colours the mind the modification is at once witnessed by the Puruṣa and it is this witnessing by the Puruṣa which brings about the ‘knowing’ of the object. The use of the word ‘witness’ for the reaction of the Puruṣa to the modifications taking place in the mind is not appropriate but is resorted to in order to distinguish it from the simultaneous mental process which is generally called perception. All our words such as ‘knowing’, ‘perceiving’ are so closely identified with the activities of the mind that a new word is really needed to indicate this peculiar ultimate reaction of the Puruṣa to all mental processes. But, in the absence of such a word in the English language ‘witnessing’ will perhaps do for the present, provided we keep in mind its special significance. This ‘witnessing’ by the Puruṣa of the modification produced in the mind is the second indispensable condition of ‘knowing’ any object by the mind, the first being its ‘colouring’ by the object. Researches in psychology have shown that the mind is frequently modified by external objects even though it is not aware of them at the time, the proof of such modifications having taken place lying in the fact that such impressions can be recovered later from the mind by hypnotizing the person. So that, the ‘witnessing’ by the Puruṣa of the modifications produced in the mind is independent of the conscious activity of the mind. This is the significance of the word Sadā which means literally ‘always’ or ‘ever’. What is meant to be conveyed in the Sūtra is that the Puruṣa is aware, in an unbroken manner, of all the changes which are taking place in the mind and it is not possible for any change to escape his notice. This is so because he is eternal. It is only a changeless, eternal consciousness which can provide such a constant and perfect background for the continuous and complex changes which are taking place in the mind. If the background itself is changeable there is bound to be confusion. You cannot project a cinema picture on a screen which itself is changing constantly.