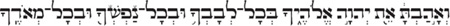

And thou shalt love the LORD thy God with all thine heart, and with all

thy soul, and with all thy might.

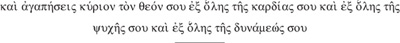

The most important commandment, according to Jesus in Matthew 22:37, Mark 12:30, and Luke 10:27, is to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind” (NAB and, essentially, NRSV).

Jesus himself (using Greek) is quoting Deuteronomy 6:5 (which is in Hebrew), and that line is central to both Jews and Christians. Deuteronomy 6:5 is part of the text that Jews traditionally affix to their doorways, and, as we just saw, Jesus calls this the most important commandment.

The combination “heart and soul,” or some variation of it, appears nearly forty times in the Bible, further emphasizing how important these two ideas were in antiquity. But here’s the problem. The Hebrew words for “heart” and “soul,” the words in Deuteronomy 6:5 that Jesus quotes, are levav and nefesh, respectively. And they are severely mistranslated. In fact, the translations miss the point entirely.

We will use the techniques of Chapter 2 to figure out what the Hebrew words really mean, and then the techniques of Chapter 3 to find a suitable translation that captures what the ancient text really tried to teach us. That is to say, we’ll start by looking at the context in which the Hebrew words levav and nefesh were used. Then we’ll look at the role they play—alone and together—and see if we have a way of doing the same thing in English. Along the way, we’ll learn about how the authors of the Bible saw the human condition, and, perhaps surprisingly, we’ll find that the original concepts mirror conversations and discussions that seem more at home in our third millennium A.D. than in the first millennium B.C., when they were first penned. Finally, we’ll see how what we learn can be applied to other quotes.

We’ll start with the Hebrew word levav, commonly mistranslated as “heart.” Our task is twofold. We want to figure out how levav was used in ancient Hebrew (as in Chapter 2), and then figure out if we can do the same thing in English (Chapter 3).

To avoid prejudicing the issue, we’ll use the original Hebrew levav in our discussions of the word, asking “What does levav mean?” in some particular place, rather than “Does the word ‘heart’ capture what levav means?” This way, we won’t have to get bogged down in the various ways that “heart” is used in English—even though the topic will come up—and more importantly, this way we can try not to be blinded by the mistakes of previous translators.

Just to get started, we might look at Song of Songs 4:9, where the noun levav is used as a verb. Of course, we have no reason to think that verbs must mean the same thing as the nouns they are related to, but in this case it sets the stage nicely. We read, “You have levaved me . . . my bride.” (We’ll deal with the missing text, most commonly mistranslated as “my sister,” in Chapter 6.) What follows are images of beauty and romance: “beautiful,” “better than wine,” “love,” references to lips and tongues, and so forth. There can be little doubt, in this context, that levaved has something to do with love and romance.

As it happens, the English word “heart” is also associated with romance, at least sometimes. The common translation (KJV, NRSV, NAB, etc.) of “ravished my heart” takes advantage of this happy pairing between English and Hebrew. But we shouldn’t jump the gun and try to find a translation yet. Our goal now is simply to figure out what levav means. And, at any rate, this verbal example is really just to get us started. Based on Song of Songs, it appears that levav has something to do with romantic love, but we don’t know nearly enough yet.

So we look at more examples. Leviticus 19:17 is a great place to continue. We read, “Do not hate . . . in your levav.” We know better than to ask, “What word represents levav here?” and instead ask, “What role does levav play?” Unlike some of the examples we’ll see in just a moment, Leviticus is relatively clear here. The levav is where hatred lies. This meshes well with what we saw in Songs of Songs, where the levav was the locus of love.

We see a pattern developing. What love and hatred have in common is that they are both emotions. The levav seems to represent emotion.

But rather than jumping to Song of Songs, we could have started at the beginning of the Bible and worked forward. Had we done this, we would have first encountered Genesis 20:5, where it’s not so clear what levav represents. In Genesis 20, Abraham misrepresents the nature of his relationship to his wife, Sarah, passing her off as his sister. Thinking Sarah is therefore available, King Abimelech nearly takes her for himself. Later, when he learns the truth, he pleads that he acted with a “levav of purity” or, perhaps, a “levav of integrity.” We don’t know for sure what this expression means—and, for now, we don’t care, but we do care what kinds of things the levav can represent.

So we note that levav here has something to do with Abimelech’s intention or his understanding, but probably not his emotions. Either he misunderstood the situation regarding Sarah, or, more likely, he had good/pure/righteous/etc. intentions. Either way, the fact is represented in Hebrew by the state of his levav.

So Genesis 20:5 isn’t definitive, but it is our first warning sign that “heart” is the wrong translation for levav. While in English the heart might represent emotions, it doesn’t extend to intentions. By contrast, it seems that levav does.

In Exodus we read about Pharaoh and his servants, who vacillate between wanting and not wanting to let the Hebrew slaves leave Egypt. In Exodus 14:5, after letting the slaves leave and after hearing that they have indeed left, Pharaoh and his servants find their levav changed. They no longer want to let the slaves go.

Again, as chance would have it, we have two convenient ways in English to represent what happens to Pharaoh and his servants in Egypt. Either “they changed their mind” or “they had a change of heart.” In spite of the different words in English, both of these expressions mean the same thing, and both are ambiguous. Did Pharaoh feel differently? Or did he think differently? We don’t know the answer from this context.

Deuteronomy 19:6 is more helpful. In the laws concerning manslaughter, murder, human retribution, and cities of refuge, our attention is turned to someone whose loved one has been killed. “While his levav is hot,” we read, he might overtake and slay the original killer. Once again, it looks like levav represents emotion. We know that “hot” across the various languages of the world tends to represent the same sorts of things (“hot under the collar” in English, for example). “Hot emotion” is exactly what we might expect from someone whose family member has just been killed. So levav can represent love, anger, intention, and something from Genesis 20:5 that we haven’t nailed down yet.

Deuteronomy 20 addresses the issue of who can and cannot go off to fight in war. After the interesting opt-out clause exempting from duty the owners of vineyards who have not yet harvested the grapes, the owners of houses who have not yet lived in them, and any fiancés who have not yet married, we find another category of people who are not sent off to war: people who are “weak of levav” or, perhaps, “soft of levav.” These weak-levaved people should be sent home, lest they “melt the levav” of their fellow soldiers. Almost certainly, the point is that cowards shouldn’t go off to fight, lest they convince the other soldiers similarly to be afraid. Accounts of warfare in the book of Joshua (2:11, 5:1, 7:5, etc.) buttress the notion that a melting levav conveys fear of losing a battle. So we add “fear” (and probably “courage”) to what levav represents.

Beginning in Deuteronomy 27, we find a litany of curses and blessings, punishment and reward, for behavior after Moses dies. Deuteronomy 30:1 tells the Israelites what to do in the future when the curses and blessings come about. They are to “return” to their levav. The idiom is confusing, because, just as the meaning of levav is complicated, so too is “return.” The KJV translates “call them [the blessings and curses] to mind” here, suggesting “remember.” We don’t know the nuances, so we don’t know if the KJV got it exactly right here, but it looks like memory, too, may lie in the Hebrew levav.

Deuteronomy 30:14 adds yet another aspect to our understanding of levav. Regarding God’s teaching, the particularly poetic Chapter 30 in Deuteronomy promises something not beyond the seas, nor ensconced in heaven, but rather very near. “It is in your mouth and in your levav. You can do it.” Ignoring the bit about the mouth for now, we ask what “in your heart” has to do with “doing it.” Various possibilities present themselves, but the most likely is that “in your levav” means “you understand it.”

If we approach the issue of levav with the (wrong) preconception that levav must mean “heart,” it might be hard to appreciate Deuteronomy 30:14. Indeed, the KJV, even though it translates levav as “mind” in Deuteronomy 27, gives us “it is in your mouth and in your heart.” But in this context, “in your heart” doesn’t mean anything in English. And certainly it has nothing to do with being able to do anything. (People who read the Bible frequently, though, sometimes encounter nonsensical phrases like this often enough that the phrases start to sound like coherent English.)

Rather than wrongly assuming that levav means “heart,” and then wrongly assuming that levav in Hebrew therefore represents the same constellation of concepts that “heart” does in English, we should now ask if we find support elsewhere for levav having something to do with understanding. We’ve already seen one place where it might (Genesis 20:5), and now (in Deuteronomy 30:14) we see another. Are there more?

In fact, there are many others. Ezekiel 38 is about Gog and Magog. Gog (a person) is the ruler of Magog (a place) and, according to the text, a threat to Israel. Ezekiel relates that the Lord commands him to prophesy against Gog of Magog. In verse 38:10, Ezekiel makes the connection between thoughts and the levav when he warns Gog that “things will arise in your levav and you will think evil thoughts.” Similarly, Zechariah’s plea to treat people nicely (Zechariah 7:10) includes: “Do not think evil . . . in your levav.” The Chronicler in I Chronicles 29:18 reports that David begs God to uphold the “thoughts of the levav of ” God’s people. Ezra (Ezra 7:10) prepares his levav for study. Job (Job 9:4), in his moving response to Bildad, argues that God is “wise of levav.” And Isaiah 6:10 is especially clear: “. . . lest they see with their eyes, hear with their ears, and understand with their levav.” So, too, is Isaiah 10:7: “His levav does not think this way.”

This expanded view also helps us understand a fairly common expression in the Bible: “to say in the heart.” For example, Deuteronomy 7:17 deals with what happens if the people “say in their levavs” that other nations are too powerful. If the levav represents thoughts and not just emotions, the expression is clear: “To say in the heart” means “to think.” The KJV missed that in Deuteronomy 7:17, but other translations tend toward “say to yourselves” instead of “say in your heart,” at least getting the right general idea. We see the same expression, with the same basic meaning of “think,” elsewhere as well.

So, clearly, the levav involves thoughts, understanding, and, in general, cogitation. In English we use the “mind,” “head,” and “brain” to represent that sort of thing: “a sharp mind,” “a feeble mind,” “comes to mind,” “use your head,” “brainy,” etc. In ancient Hebrew, thinking took place in the levav.

As it happens, we have an expression “thinking with your heart” in English. It would be easy to make the inappropriate leap from the Hebrew phrase in which a levav thinks to the seemingly similar English one. But the English phrase has a particular meaning. “Thinking” with the heart isn’t really thinking at all. It’s responding with emotion to the exclusion of rationality. A schoolgirl in love, for example, who “thinks with her heart,” is specifically not thinking rationally. She is reacting emotionally.

We have seen nothing in our Hebrew examples to suggest that the levav excludes rationality, and, in fact, these most recent examples suggest the opposite. The levav in Hebrew, unlike the “heart” in English, can specifically be the site of rational thinking and understanding.

But ancient Hebrew also used the levav for emotions, as we saw in Leviticus 19:17, Deuteronomy 19:6, and potentially Song of Songs. Other examples support this side of levav: Proverbs 6:25 connects romantic beauty and the levav. Isaiah 7:2—in the same sort of prose that used levav for thinking and understanding—notes David’s profound sorrow at hearing that Ephraim has joined Syria in attacking Jerusalem. David suffers in his levav. Isaiah 21:4 connects the levav with fear or panic, as does Jeremiah 32:40.

So our final list of concepts associated with levav is this: love, hatred, fear, courage, intention, understanding, and thinking.

We noted above that modern American culture seems to separate rationality from emotion, putting one in the mind and one in the heart. The word levav shows us that the ancients saw the two as connected. Both emotion and rational thought were in the same place—namely, the levav.

The word “heart” is a terrible translation to convey this combination of concepts, because that English word specifically excludes half of what the ancient Hebrew word meant. But precisely because we tend to distance emotion from rational thought, we don’t have a good modern English word to represent them both. “Psyche” might work—or, at least, be closer—but it is clearly the wrong register. The levav was a common part of how the ancients viewed their lives, while the same cannot be said for “psyche.”

Furthermore, based on external evidence like how the Hebrew word was translated into other languages, it seems that the levav, in addition to everything else, was also an anatomical organ—or, at least, some physical part of the body. The point of levav was to pinpoint where thinking and emoting takes place in our bodies. Just as modern English puts the thoughts in the brain and the emotions in the heart, Hebrew put both in the levav. (In this regard, the Hebrews’ culture was similar to the Greeks’. Aristotle thought that the heart was used to think and that the brain’s purpose was merely to cool off the body. He was close. The brain does cool the body, but it does much more than that.)

In the end, we don’t have a good English word for levav, at least not when levav is used by itself. But as chance would have it, English gives us a fine phrase to capture the combination of levav and nefesh. So we turn to that Hebrew word next.

We first find the word nefesh in Genesis. As an example of how it’s used, we consider Genesis 1:30: “[I have given green plants for food] to every beast of the earth, and to every bird of the sky, and to everything that creeps on the earth, and to everything that has the nefesh of life” (NRSV). It looks like every living being has a “nefesh of life,” though the Hebrew grammar leaves open another possibility, too. Every living being may have a “living nefesh.”

Unfortunately, many people already (wrongly) “know” that nefesh means “soul,” so they jump to the conclusion that in Genesis 1:30 God puts a soul in every living being. It’s a lovely thought. But there’s no support for it in the text. Based on just Genesis 1:30, nefesh could mean “cell” or “blood” or “eye” or any of the other myriad things that walking, flying, and creeping creatures share.

Or it could mean “life force” or “destiny” or some other ethereal quality. Genesis 1:30 is so vague that it tells us little beyond the fact that nefesh seems to have something to do with life. And even that could be wrong—again, just based on Genesis 1:30—if the Hebrew means “living nefesh,” because in that case there might be two kinds of nefesh, a living one and a nonliving one.

Fortunately, the situation will become much clearer, but Genesis 1:30 is an important reminder that we should not use a preconception of what a word could mean to prejudice our investigation of what a word really means. We want to look to each example for evidence of what the word nefesh means, not for confirmation of a wrong preconception of what we want it to mean.

Genesis 2:7 gives us a little more information. God breathes the breath of life into Adam, and Adam becomes a “living nefesh.” Again, it seems that nefesh has something to do with life, because Adam didn’t become a living nefesh until life was breathed into him. But we still don’t know if “living nefesh” is poetically redundant or if there can be a “dead nefesh.”

Genesis 2:19 uses the same phrase, “living nefesh,” to mean the animals, buttressing the idea that nefesh has something to do with life—but we still have precious little information. So far—if animals have a soul—“soul” is one possible meaning for nefesh, but we have not seen anything specifically to point in that direction, and we have lots of other reasonable options.

Genesis 9:4 connects “flesh,” “blood,” and the nefesh, but, unfortunately, the Hebrew grammar is confusing. The KJV translates, “But flesh with the nefesh thereof, which is the blood thereof, shall ye not eat.” (Ironically, because the Hebrew grammar is confusing, the confusing English grammar of the KJV is appropriate here.) The KJV translation implies that the nefesh is the blood. That’s one possibility, another being that nefesh is connected to “flesh,” and the “blood” represents the combination.

Genesis 9:15 continues in the vein we just saw, using “living nefesh” for any live animal, including humans.

English has a deficiency that Hebrew may not have had. In English, it’s hard to group animals and people together while still not denying that people are animals. Most of us in the modern world consider people part of the animal kingdom but are yet somewhat uncomfortable specifically calling people “animals,” except to stress some particular animalistic behavior. Statements such as “People have a lot in common with animals” coexist with “People are a kind of animal, too.” Carl Sagan’s observation from Chapter 2 (page 16) about women and pain in childbirth is difficult even to express in English, because phrases like “women, more than any other female animal . . .” grate at the ear of the modern English speaker. Perhaps “living nefesh” was a way around this, a way specifically to include people and animals in one neat category. It would be a convenient thing for a language to have, but this interpretation of “living nefesh” is little more than speculation. And regardless, we don’t want to get bogged down by one phrase that happens to contain nefesh.

Genesis 14 relates the battle of the four kings against the five, an ongoing altercation that takes place near Sodom and Gomorrah over the course of two decades. Abram (Abraham’s name until God changes it in Genesis 17:5) gets involved after his nephew Lot, who had settled in Sodom, is captured. And after Abram successfully rescues Lot, capturing other people and things taken from Sodom along the way, the king of Sodom offers a deal to Abram. In Genesis 14:21, the king says, “Give me the nefeshes, and you take the property.” (Abram rejects the offer, not wanting to give the king of Sodom the bragging rights as the one who “made Abram rich.”) The word nefesh here almost certainly refers to “person.” We must ask, though, if this is what the word means or if we have a case of metonymy here. (Remember that “metonymy” means using a word for something related to the word, like “hands” for “people who have hands.”) If nefesh meant “life” (as the KJV thinks it does in Genesis 9:4), it could easily have morphed metonymically into “something that has life,” specifically a person.

In fact, we see the same progression in English. We’ve already seen the phrase “not a soul was left in the room.” Similarly, in some parts of the country the English phrase “bless his (or her) soul” is a way of referring to a person. Death reports from accidents at sea report how many “souls were lost,” again referring to people, not just their souls.

Genesis 46:18 shows us this same potentially metonymic use: “These are the children of Zilpah, whom Laban gave to his daughter Leah; and these she bore to Jacob—sixteen nefeshes.” Zilpah didn’t give birth to amorphous life forces or to “lives,” but rather simply to people.

And presumably these people to whom she gave birth were babies at the time. But that doesn’t mean that nefesh specifically means “baby.” Rather, we have a demonstration here of another potential way we can misunderstand ancient Hebrew. A word doesn’t always convey everything that the reader has to know. Some things come from context, background, other parts of the text, etc.

So here, nefesh means “person” of any age, and, from context, we determine that these are baby people. It’s an obvious point about the word nefesh, but an important general principle. We have to be careful to distinguish between what a word means and what we can gather from context. To consider one more silly example, certainly the word nefesh here doesn’t mean “children born to anyone named Zilpah.” In the case of person/child/child-born-to-Zilpah this obvious fact is clear. Context can supplement the meaning of the words. Another example might come from the English statement “Billy has a pet at home.” The pet might be a dog. But even if everyone knows that Billy’s pet is a dog, “pet” still includes cats and fish and whatnot.

Because of the widespread desire to find deeper meaning in the Bible, people sometimes want to put deeper inherent meaning into the individual words of the Bible. For example, some people want Genesis 46:18 (“these are the children of Zilpah . . . sixteen nefeshes”) to allude to the potential of a new human being. Or they want Adam, in Genesis 2:7 (where Adam becomes a “living nefesh”), to become more than just alive. They want him to embody humankind. These can all be true (or not) regardless of what the actual words mean, but until we know what the words mean we will be misreading or misinterpreting the Bible rather than reading or interpreting it.

Still, perhaps nefesh refers to one aspect or another of human life. Just as levav tends to represent thoughts and emotions, perhaps nefesh does indicate human potential, or God-givenness, or other lofty matters. We have seen nothing to suggest anything more specific, but neither have we seen anything to rule it out. So we keep going.

Discussing the regulations for Passover, Exodus 12:16 reinforces the idea that nefesh means “person”: “[on Passover] only what will be eaten by each nefesh shall be prepared. . . .” Here, nefesh again refers to a person, but it specifically refers to the aspect of a person that does the eating.

Leviticus highlights the nefesh’s relationship to eating. Leviticus 7:18, for example, is essentially a guide to how long meat can be kept before it goes bad. It warns against eating the meat of a sacrifice after the second day, cautioning that the “nefesh that eats of it” will be guilty of an off ense against the Lord. Leviticus 7:27 cautions anyone who “eats any blood” (drinks, I guess we would say in English), again using the word nefesh: “Any nefesh that eats any blood” will be cut off . . . .

This connection between eating and the nefesh—or, at least, the compatibility between nefesh and eating—is our second clue that “soul” is a terrible translation for nefesh. (The first came from Genesis, where nefesh seems to have something to do with the blood and the flesh.) English speakers will disagree about what, exactly, is meant by “soul.” For some, it’s the intangible core of a person. For others, it’s the essence that lives on after death. Some people don’t believe in a soul. Yet no one uses “soul” specifically for the part of being alive that involves eating.

Leviticus 17:11 is even more of a problem. It offers a reason why eating blood is forbidden: “The nefesh of flesh is in the blood.” The whole line reads: “For the nefesh of the flesh is in the blood: and I have given it to you upon the altar to make an atonement for your nefeshes: for it is the blood that maketh an atonement for the nefesh” (KJV). Surprisingly, the KJV translates nefesh as “life” the first time but “soul” the next two. The problem faced by the King James’s translators is that the soul, as the word is and was used in English, isn’t in the blood.

What we have here, though, is classical magic—that is, using a thing to affect that very thing, like dressing up as a daemon to repel daemons or, as they did in ancient Egypt, using a pig’s eye to cure eye disease. In the case of Leviticus, the idea was that blood could affect blood. More specifically, blood could affect the nefesh, a process “explained” by the fact that the nefesh is in the blood. We are left wondering, though, what part of human existence might lie in the blood.

Certainly “soul” is the wrong answer. The human soul—whatever it is—does not lie in the blood. Just looking at the first part of Leviticus 17:11—the nefesh is in the blood—we find lots of options for nefesh: hemoglobin, for example, or dissolved oxygen, or even pressurized hydraulic flow. But, obviously, none of those concepts works with the second half of the line or, more generally, with what we have already seen. And at any rate, the authors of the Bible seemed to be unaware of our modern medical taxonomy.

To summarize, then, at this point we know that nefesh has something to do with life, can be used to mean “person,” can specifically refer to the aspect of being alive that involves eating, and is in the blood. Certainly we have no English word for that.

Leviticus 24 gives us more clues about nefesh. In Leviticus 24:17, we read that anyone who mortally wounds the nefesh of a person will be put to death. The next verse adds animals, declaring that anyone who wounds the nefesh of an animal will pay for it, by paying a nefesh for a nefesh.

These laws have nothing to do with souls—at least, not directly. We do not wish to rule out the possibility that the reason behind the laws has (or doesn’t have) something to do with the immortality of the soul and the inherent value of life. But the passages are very clear. Leviticus 24:17 is about killing a person, and Leviticus 24:18 is about killing an animal. The KJV, recognizing the difficulty of using “soul” to convey these simple ideas, translates “a nefesh for a nefesh” as “beast for beast.” But in so doing, they have paraphrased, not translated. (The KJV uses “beast” where I have used “animal.” Neither translation is entirely accurate, because the Bible divides animals into different categories than we do, using different words for domesticable and undomesticable wild animals. “Animal” is too broad, while “beast” has the wong connotation.)

Numbers answers the question that arose in Genesis about whether “living nefesh” is redundant, because Numbers 6:6 forbids Nazirites from approaching a corpse. But the phrase for corpse there is “nefesh of the dead.” So, it seems, both the living and the dead have a nefesh. Once again, “soul” is a terrible translation, and no major publication uses it for nefesh here. Instead, we generally find “dead body” or “corpse.” Our question now is not what Numbers 6:6 means, though. We know what it means. We want to understand how the words combine to create that meaning.

It’s like a complicated riddle: What do living animals and people have? And it has something to do with the flesh. And it’s in the blood. And it sometimes means “person.” And it sometimes means “animal.” And it has something to do with eating. And it means “corpse.” (And let us not forget the part that raised the issue in the first place: You use it to love God.) Fortunately, we’ll find a clear answer soon.

Psalm 63 adds another piece of the puzzle. Hebrew poetry, as we saw on page 39 and then more extensively in Chapter 3, often relies on synonyms or near synonyms (“saying the same thing twice”), the poetry of a passage coming from the particular words the author chooses to put in parallel. We can use this to help us know when two words significantly overlap. Psalm 63:1 (“. . . my nefesh thirsts for You, my basar longs for You . . .”), numbered 63:2 by Jews, puts nefesh in parallel with basar. The second word means “flesh” or “meat,” so we have a clue that nefesh has something significant in common with flesh. Yet again, we see that “soul” is a terrible translation, but, surprisingly, the KJV and the NRSV both chose to use it to translate Psalm 63:1.

We see similar evidence in Ezekiel 4:14, where Ezekiel assures God that his nefesh has not been polluted by eating the wrong things. In isolation, this verse in Ezekiel doesn’t tell us much—we don’t know for sure what part of the body or mind or soul or whatever was affected by food. But the most natural interpretation is that eating the wrong things is bad for the body.

I Kings 17:22 gives us another crucial bit of evidence. Elijah, while fleeing King Ahab, finds himself in the house of a widow whose son was so sick that before long “there was no breath left in him” (NRSV)—that is, he died. (The word for “breath” here is the Hebrew n’shama. Some translations use “breath” for the Hebrew nefesh, so we have to be careful. We do not want to define a word using the word itself or, worse, using a bad translation of the word itself. But even though in some English translations it looks like we’re using “breath” to define “breath,” we are actually just using n’shama to define nefesh.)

Elijah revives the dead boy by laying him down (I Kings 17:19) and stretching himself over the boy (I Kings 17:21), after which the nefesh “of the child came into him again, and he revived” (KJV). What we have in I Kings 17 is almost certainly an ancient case of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Elijah’s disciple, Elisha, seems to have learned the procedure from his mentor. In II Kings 4:8, Elisha happens upon an old childless Shunammite woman (that is, a woman from a place called Shunem). Elisha prophesies to the woman that she will conceive. She does, and bears a son. By II Kings 4:31, the son is lying dead on his bed. But, fortunately, Elisha is around again. Elisha “lay upon the child, and put his mouth upon his mouth . . . and the child sneezed seven times, and the child opened his eyes” (KJV).

Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation would have been a perfectly reasonable thing for the ancients to try. They surely knew that living people had breath and that dead people did not. Particularly before the advent of modern science, which showed us that people inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, it would have been preeminently sensible to try to put breath into someone who had none of his or her own. (Even though respiration uses up oxygen, so people exhale less oxygen than they inhale, they still exhale enough oxygen to give life. That’s why mouth-to-mouth works. But Elisha would have had no way of knowing about this potential problem or its resolution.) Elijah, it seems, was skilled in the technique, and he taught it to Elisha.

For our current purposes, we are particularly interested in the last phrase of I Kings 17:21 (about Elijah and the widow’s son), in which “the nefesh of the child came into him again.” The most natural interpretation of nefesh here is “breath.” After all, the boy had no breath, Elijah blew into his mouth, and then the boy had a nefesh again.

If so, here’s what we know so far: The nefesh has something to do with life. All life forms have some connection to a nefesh. (Maybe they are one; maybe they have one. The Hebrew grammar is imprecise here.) At least potentially, nefeshes come in two varieties, living and dead. The word nefesh is so connected with life that it is used metonymically to mean (human) “person” or (human or animal) “body.” These are all broad connections with life.

But we also have more specific information. From Genesis 9:4 we know that nefesh is somehow connected to the flesh and to the blood. From Leviticus 17:11 we know that nefesh is directly connected to the blood. And from the books of Kings we now know that nefesh is directly connected to the breath.

What “flesh,” “blood,” and “breath” have in common is that all three are tangible aspects of life. One can hold flesh, touch blood, and feel breath. Flesh and blood are always visible, and in cold weather, so too is breath. The loss of any one of these physical things causes death. The ancients knew that a wound to the flesh could be fatal. Blood loss could be fatal. And what they perceived as loss of breath could be fatal. (Now we tend to see things the other way around, conceiving of the loss of breath as a symptom, not a cause. But in fact, the ancient view is equally accurate. People do live on for at least a few moments after they stop breathing. That’s why mouth-to-mouth works. The ancients also must have known about drowning.)

The word nefesh, then, seems to have referred specifically to everything about life that could be touched. In the Bible, the three most central touchable parts of life were flesh, blood, and breath. (In modernity, too, those three seem like reasonable choices for the parts of life that can be touched.) The physical body is an extension of “flesh.” Human life is only a bit more of an extension. (In English, we have a phrase, “flesh and blood.” It plays on the same themes.) What dead people still have, even when their life force has left them, is a body. That explains Numbers 6:6, where “nefesh of a dead person” was used for “corpse.” And it explains why the nefesh is the part of the human condition connected with eating. Eating is a physical act, and the nefesh reflects physical existence.

We now see that “soul” is a particularly disastrous translation of nefesh.

The English word “soul” means different things to different people. For some, it is the essence of life—generally, though not always—human life. For others, it has more to do with life after death. (The French scholar Ernest Renan, one of the leaders of the post-Kantian French school of critical philosophy, is reported to have pleaded, “O God, if there is a God, save my soul, if I have a soul.”) But however it’s used, “soul” in English always emphasizes the untouchable, ethereal, amorphous aspects of life. The nefesh is just the opposite.

But before we find a more accurate translation, we look at nefesh and levav as they are used together.

We have seen that levav represented thoughts, emotions, fears, etc. When we compare levav to nefesh, we find another, more accurate, and succinct way to express levav. While nefesh was everything about life that could be touched, levav was its counterpart, representing everything about life that could not be touched.

In other words, the Biblical view was that our lives have two parts: our physical side (nefesh) and our harder-to-define, impossible-to-see nonphysical side (levav).

We don’t have anything like that in English for human life, but we can understand the concept by looking at two words from the realm of computer science: “hardware,” which, like nefesh, is touchable; and “software,” which, like levav, cannot be touched. (Or, as the saying goes, the software is the part of the computer you can’t kick.)

The nefesh was like the hardware of humanity and the levav like the software.

It should not surprise us, then, that levav and nefesh were used together to form an expression. And it is precisely that expression that appears in what Jesus calls the most important commandment. We are supposed to love God with everything about us that makes us human. Unlike the usual English translation, which limits the commandment to our “heart,” excluding our thoughts, the Biblical commandment includes emotions and thoughts and more. And again unlike the usual English translation, the Biblical commandment specifically addresses our corporal, physical existence.

Even though we don’t have specific words in English for the tangible versus intangible aspects of life, we are lucky that we have an expression in English to combine both: “mind and body.”

The past few decades have seen increasing interest among Western doctors and researchers into the “mind-body” connection. Even though the word “mind” is usually limited to rational thought, not emotion, and even though the word “body” does not normally refer to the breath, in the phrase “mind-body” both terms are broader and more inclusive. The point of the mind-body connection is precisely that our physical well-being is intimately connected with our non-physical well-being. Sorrow or anxiety can cause physical illness. Good news can help an ailing patient. When researchers proclaim a “connection between the mind and the body,” they are referring to the levav and the nefesh. They are also reaffirming something the authors of the Bible knew three thousand years ago.

Furthermore, like “mind-body” in English, the combination of levav and nefesh in Hebrew formed a common expression in the Bible, and we see it not just in Deuteronomy 6:5. Deuteronomy 4:29, for example, promises that “you will find [God] if you search after him with all your levav and nefesh” (NRSV). Joshua 22:2 commands, “Serve [God] with all your levav and with all your nefesh.”

I Samuel 2:35 equates a “faithful priest” with someone who will “do what is in my [God’s] levav and my [again, God’s] nefesh.” The reference to God’s levav and nefesh is further evidence that the combination is not meant to be taken literally. In I Kings 2:4, David instructs Solomon about God’s promise that “if your [David’s] children walk before me in truth with all their levav and with all their nefesh,” then the line of David will never end. And so forth.

Accordingly, we can translate Deuteronomy 6:5—and therefore also Matthew 22:37, Mark 12:30, and Luke 10:27—as “love the Lord your God with all your mind and body. . . .” The mind-body connection is new to the Western world, but it was a key part of how the Bible understood the human condition, and it formed the basis of this central commandment.

We have now investigated the two words levav and nefesh, along the way learning about how the Biblical authors viewed life. To understand Matthew 22 (and Mark 12, Luke 10, and Deuteronomy 6:5), we need to fill in two more puzzle pieces.

The first is the verb in Jesus’ commandment. The Hebrew is ahav, normally translated as “love.” It is indeed similar to the English concept of love, but like in English it has many meanings and depends on context. Loving ice cream is different than loving a spouse, which is different than loving a child, which in turn is different than loving one’s country. The English phrase “love . . . with your heart/soul” necessarily stresses the emotive part of “love,” because of the connection between love and the heart in English. Our new translation, “love . . . with your mind-body,” leaves open broader possibilities.

The second loose end is the last word of the phrase (m’od in Hebrew). And it is more troublesome. The KJV translates it as “might,” and most other translations agree. But unlike levav and nefesh, which frequently appear together, we find the addition of m’od only in Deuteronomy 6:5 (which Jesus cites) and in II Kings 23:25, where it is probably a paraphrase of Deuteronomy 6:5. And while m’od is a noun in those two places, elsewhere it has adjectival or adverbial force. It usually means “very,” as in God’s famous observation at the end of the sixth day that everything was “very good.” It’s as though the phrase in Deuteronomy reads, “. . . all your mind and body and very.”

With so little context to help us understand m’od in Deuteronomy 6:5, we are forced to guess what it might mean. Two logical possibilities present themselves, and it’s hard to choose between them. The word m’od may summarize levav and nefesh. Or it might augment them. In the first case, the verse would mean: “love . . . with all your mind and body,” that is, “all your m’od.” Or it might mean “. . . with all your mind and body” and, in addition, “all your m’od.” The KJV takes the second position.

A Greek translation from the third century B.C. called the Septuagint (which we discuss in more detail on page 212) translates m’od here as dunamis, a word otherwise used to mean “strength.” This is where we get the common translation, “(heart and soul and) might.” But even the Gospels didn’t agree on how exactly to finish the quote. Furthermore, m’od doesn’t usually seem to mean “might,” and usually dunamis is used for other Hebrew words. Still, if the notion is “power to change the world”—as suggested by some theologians—then this would make a fitting ending for the commandment.

While Matthew, Mark, and Luke agree on the quotation up to levav and nefesh, their continuations differ, suggesting that we are not the first generation to wonder what to make of the third word, m’od.

Though the dilemma is linguistically frustrating, it is perhaps appropriate that only two thirds of the commandment is clear. We have to figure out the remaining third for ourselves.

More generally, in addition to understanding Jesus’ commandment, we gain considerable insight into what it means to be human. We exist in the physical world. We exist in the nonphysical world. And there’s something else, maybe our power to effect change, that we don’t quite understand.