Behold, a virgin shall conceive

Isaiah 7:14, quoted in Matthew 1:23, predicts that the Lord shall give a sign in the form of a “virgin” (KJV) who shall conceive. This virgin has been widely interpreted to be Mary, mother of Jesus, and Isaiah’s prophecy is therefore a cornerstone of Christian theology.

But the word doesn’t mean “virgin,” so the prophecy isn’t what is seems.

The Hebrew in Isaiah is alma. We now know how to figure out what the word really means. As we follow the same path we did in previous chapters, we’ll also need a bit of general background about words that are used to mark age and societal roles.

There were no teenagers in antiquity.

Of course, on their way to their twenties people stopped off at thirteen years old, then fourteen, etc., but “teenager” wasn’t a stage of life the way it is now.

The famous King Tutankhamun, for example, died before he was twenty, so technically he was a teenager, but he wasn’t what we think of now as a “teenager.” He was what we now would call an “adult.”

Along similar lines, researchers such as David Tracer believe that crawling—a defining stage of childhood in modern Western countries—may be only a couple hundred years old as a widespread human behavior. Tracer also notes that to this day, parents in many cultures carry their children until they are old enough to walk. This illustrates how difficult it can be to imagine cultures vastly different than our own.

Estimates vary, but it seems that the average adult in ancient Egypt died before age forty. The life expectancy was considerably lower—by some estimates as low as twenty—because life expectancies are expressed as averages, and when roughly one-third of people die before their first year, often before their first week, the average drops considerably. But even among the probably 50 percent of people who were lucky enough to live past infancy, most were dead by the end of their fourth decade.

Accordingly, people didn’t have time as they do now to spend their first decade as carefree children, then find themselves in their teen years, explore the world as twentysomethings, and settle down as thirty-somethings. They’d be dead before they ever really started living.

Rather, people were “children” and then they were “adults.” (And then they were dead.)

Girls in ancient Egypt married around age twelve to fourteen, and boys just a little later. What we now call “middle schoolers” were, back then, newlyweds or even proud new parents.

We have less concrete evidence for ancient Israelite society, and numbers vary widely depending on the approach. If we take the Five Books of Moses literally, life spans near 1,000 years were not uncommon in the days before Abraham. In the time of the patriarchs and matriarchs, people often lived well into their second century (imagine a midlife crisis at age 100). Moses lives to 120. And only in the rest of the Bible did people usually die at ages that are now considered common.

But this very pattern suggests that more is going on than meets the eye. Of these three groups of ages, the first is wildly exaggerated by modern standards: No one lives to be 950, as Noah did according to Genesis 9:29. Nor do people live to be 180, as Isaac did. Moses’ life of 120 years is possible but rare, right on the border between possible and impossible. And after Moses, in the time of Kings and so forth, life spans drop considerably.

This threefold division according to ages mirrors three types of distinctly different content in the Bible.

The text from Adam to Abraham seems primarily to address the entire world—how the world came to be, the invention of music, the Neolithic Revolution (that is, the move from a hunter-gatherer society to one built on farming, and the accompanying change from a nomadic and poorly fed culture to a more sedentary one with a surplus of food), the diversity of languages and culture, and so forth.

The text from Abraham through Moses addresses the formation of the Israelite nation, including the patriarchs and matriarchs, the laws of ancient Israelite society, etc.

And the text thereafter deals with Israelite life in ancient Israel.

The fact that people’s ages are so different in these three sections (many hundreds for the part about the entire world, a few hundred for the part about forming the Israelite people, and generally less than one hundred for the part about Israelite society) suggests that the authors of the Bible knew and perhaps wanted to highlight the differences among these three parts. They may even have wanted to underscore the historical nature of the third part.

Furthermore, it is probably no coincidence that historians (using evidence from history) believe that the historically accurate section of the Bible begins precisely with that third part. In other words, internal evidence (ages) and external evidence (history) both point in the same direction. The third part is mostly history.

If so, we can look at the detailed history of Israelite kings to get a general sense of how long people lived in ancient Israel. Kings tended to start their reign around age twenty-two and they died in their mid-forties. Kings probably lived longer than the average man, and by almost any calculation lived longer than the average woman, because childbirth was frequently lethal in antiquity. These figures match the Egyptian figures closely and, quite obviously, differ starkly from modern norms. By U.S. law, for example (Article 2, Section 1 of the Constitution), the president must be at least thirty-five years old. At age forty-three, John Kennedy became the youngest man elected president. Theodore Roosevelt (who was sworn in after his predecessor, William McKinley, was assassinated), served at age forty-two. But in ancient Israel they both would probably have already been dead.

It’s harder to figure out when ancient Israelites married, but as a rough guess we can assume that girls married around age twelve to fourteen, and boys later, perhaps as late as their twenties.

So a twelve-year-old girl—now considered a “preteen” or “middle schooler,” among other options—could have been a bride. On average, women in this country today have their first child around age twenty-seven. The same twenty-seven-year-old could well have been a grandmother in ancient Israel. If she was lucky enough to live to forty-five, a woman in antiquity would probably have been a great-grandmother many times over. At that same age, a woman in the United States stands a reasonable chance of giving birth to her first child. A “young mother” today is nearly double the age of an ancient “young mother.”

All of this is important because, as we will see next, we tend to intermix terms that denote age, behavior, and social role.

Status

We just saw that a twelve-year-old might be called either a “preteen” or a “middle schooler.” These terms represent two different ways of expressing almost the same thing.

The theoretical inexactitude of using a role to indicate age, or vice versa, isn’t generally a problem. Both “preteen” and “middle schooler” almost always mean the same thing, even though an adult can, at least theoretically, be in middle school, and even though a twelve-year-old can (illegally, in this country) drop out of school. These terms demonstrate an important point. Age can be measured by category (“preteen”) or by something associated with that category (“middle schooler”).

Similarly, the phrase “giddy as a schoolgirl” uses “schoolgirl” to mean “a girl of the age at which she would be in primary school,” whether or not she is actually in school.

People who speak the language and who are familiar with the culture don’t usually have any difficulty knowing if a word refers to status or to the people who generally have the status—that is, people who are at the age where the status is typical.

By way of a third example, “grandpa” (or “gramps”) can be used to address any old man—that is, any man who is at the age where he might reasonably be a grandfather.

And here we start to see how tied to a particular culture these terms are. We might imagine a denizen of ancient Israel somehow reading a story in modern American English. That ancient Israelite, seeing “gramps,” might reasonably draw one of two wrong conclusions about the word. The reader might think that “gramps” refers to someone whose children have had children. While that is one meaning of the word, it is not the only one, or even the most common one.

Or the ancient reader might correctly recognize that “gramps” is an instance of using status to represent age. But here too, without a solid understanding of America, the reader would think that “gramps” means a man in his early forties.

So we see that the notion of status, which we might also refer to as “societal role,” can be used instead of age.

It works the other way around, too. “Teenager” refers to age, but, more often, it refers to status. “Teenagers” are people in their teens, but equally people in high school. A teacher might say he “teaches teenagers,” even though “high schoolers” would be more accurate.

The term “coed,” originally an abbreviation of “coeducation,” at first referred to the phenomenon of coeducational college education. Then it became an adjective describing the state of having men and women together. But because women joined previously all-male institutions much more frequently than the other way around, “coed” eventually took on the meaning of the people—that is, the female students—who joined the hitherto male institution. A “coed,” then, was a female student. But, in fact, a “coed” doesn’t have to go to school at all.

The “American Coed Pageants,” for example, are for girls and young women, regardless of whether or not they go to school. The three oldest categories are “Jr. Teen,” “Teen,” and “Coed.” Though they are technically a mixture of ages and roles, no one is confused. That’s because, as we have seen, ages can be used for roles and roles for ages.

This is one of two ways in which age terms are ambiguous. To understand similar words in the Bible, we have to appreciate the other way as well.

Behavior

In addition to referring literally to age or to societal role, both age words and role words can refer to people who typify what is expected of a particular age or role.

For example, a grown man who is “being a child” is acting in a way that children often do. Certainly the man is not actually a child, nor do all children act the way he does. Instead, “child” is used as an abbreviation for “a person who acts the way children often act.”

Obviously, this sort of usage is particularly sensitive to cultural norms. There used to be a standard that children should be “seen and not heard.” But “being a child” in America does not mean being “seen and not heard.” For that matter, children are generally shorter than adults, but “being a child” doesn’t mean “being short.” Rather, it generally means acting immaturely, a term that is only slightly less relative to culture, because one culture’s “mature” behavior might well be what another calls “immature.”

“She’s such a twelve-year-old” in modern America might mean a girl who plays with makeup and is experimenting with defying her parents. A similar expression in ancient Israel might have meant a newlywed. That’s because different things express the essence of “twelve-year-oldness” in different cultures.

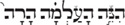

With this background we are in a position to return to Isaiah 7:14 and, therefore, Matthew 1:23. Most of the line is mostly clear: “Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; Behold, ha-alma hara, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel” (KJV). The KJV translates ha-alma as “a virgin” (even though ha- means “the,” not “a,” as we will discuss) and hara as “shall conceive,” giving us the familiar translation and the dominant theme of Matthew 1:23. (“Immanuel” in Hebrew literally means “God is with us.”)

To understand the line, we have to know what alma and hara mean. In terms of the former, we will have to look at the word alma and also at the similar words na’arah and b’tulah, all three of which have related meanings. Then to figure out the correct translation, we’ll have to incorporate the difference between age and status that we just saw. After that, we’ll see that it’s not hard to decode the word hara. Then we can deal with “the” and “a.”

We’ll start with a diversion through German that helps illustrate the issues involved.

A German Diversion

In 1534 Martin Luther published a Bible commonly called the Luther Bibel, or, in English, the “Luther Bible.” More accurately, the version is called the unrevidierte Luther Bibel, or “unrevised Luther Bible,” in contrast to a 1912 version that enjoys the name “revised Luther Bible.” We’ll look at the 1912 version, which is basically written in modern German.

The translation of Isaiah 7:14 uses the word Jungfrau for the Hebrew alma. Jungfrau is clearly a compound of jung (“young”) and frau (“woman”). It seems, therefore, that Jungfrau would probably mean “young woman.” But it does not. It means “virgin.”

We already know that etymology and internal word structure are unreliable indicators of what a word means, so we shouldn’t be surprised if looking at jung and frau in isolation leads us astray here. (In this case, it’s hard to know if we’re looking at etymology or word structure.)

Nonetheless, the form of the word highlights a fairly obvious point: There’s a conceptual connection between youth and virginity. The form also suggests that, at the time the word was coined, the stereotypical role of young women was that they were virgins. Once again, we know better than to use the form of a compound to figure out its meaning, but even so, what we have is suggestive of a particular connection between age and role, the same sort of thing that we saw with “middle schooler” and “preteen” in English. In this case, we find the literal “young woman” used to mean “virgin.” “Young” measures age, and “virgin” measures societal role. This pairing is hardly surprising. But it serves to emphasize both the obvious connection and the difficulty in translating these sorts of words accurately.

As it happens, the German Jungfrau is used to translate not only alma, but also the common Hebrew words b’tulah and na’arah, even though other German words are also used for na’arah and alma. In short, there is only partial correspondence between the original Hebrew and the German terms: Jungfrau, as we have seen, and also Dirne and, rarely, Mädchen, two more German words that roughly mean “young woman.”

To make matters worse, an even more updated 1984 version of the Luther Bibel (also called revidierte, that is, “revised”) sometimes uses Mädchen where the 1912 version has Dirne.

The reason we look at these German translations is that we have other ways of figuring out what the words mean. For example, “the virgin Mary” is called Jungfrau Maria, and we know that the point of that phrase is that Mary (Maria) was a virgin, not merely that she was young.

In the end, we see exactly what we expect: a variety of German words are used to represent age and role. There is significant overlap among the words. The meanings of the words cannot be deduced from their etymology or structure. And the words change meanings over time.

We will see exactly the same pattern in the original Hebrew and in the influential third-century B.C. Greek translation known at the Septuagint.

Hebrew

So we return to alma, na’arah, and b’tulah. We know how to figure out what they mean. We look at the contexts in which the words are used.

We’ll start with na’arah, but we’ll quickly end up looking at the three words all at once, because they are so frequently used together.

Before we actually look at the word na’arah, a caution is in order. The word na’arah is the feminine version of na’ar. As such, we would expect it to be spelled with a final heh in Hebrew, following the pattern of most masculine/feminine pairs. Frequently, however, that final letter is missing in the Bible. There are so many possible reasons for this spelling anomaly that it doesn’t help us understand the word. For example, it could be that a na’arah and a na’ar were so close in meaning that they were sometimes spelled the same way. Or, contrarily, perhaps the words were so different in meaning that there was usually no chance of any confusion, so there was no reason to spell the words differently. We note the fact only because readers who want to find the word na’arah in the original Hebrew should be aware of it.

The word na’arah first appears in Genesis 24:14. Abraham’s servant, at Abraham’s request, has traveled to the place called Aramnaharaim, where he is to find a wife for Abraham’s son Isaac. The servant prays for a sign in the form of a na’arah who will come to draw water. The servant will ask the na’arah to lower her water jug, and the na’arah will oblige.

In the next verse, Rebekkah appears with a water jug on her shoulder.

And in Genesis 24:16, Rebekkah is described as “a na’arah who looks very good, a b’tulah, and no man had had sex with her.” So it seems that a b’tulah is a kind of na’arah.

Based on Genesis 24:16, though, two possibilites for b’tulah present themselves.

The first possibility is that there are two kinds of b’tulah, one who has had sex and one who has not. And to make the matter clear, Genesis 24:16 explains that this is the second kind of b’tulah. Just as b’tulah explains what kind of na’arah Rebekkah was, so too the next phrase might explain what kind of b’tulah she was.

The other possibility is that “no man had known her” is in parallel to b’tulah, and that it explains what b’tulah means. That is, the phrase is for emphasis or poetic force.

Other contexts, give us a clearer picture of what b’tulah means.

Leviticus 21:14 explains whom a priest can marry. He cannot marry “a widow, divorcée, or profaned whore.” Rather, he must marry a b’tulah. (We use the word “divorcée” for the Hebrew word grusha with some caution. As we saw in Chapter 6, we don’t know enough about divorce in the Bible to know that the ancient practice created what we now call “divorcées.” The word literally means “one who is cast away.”) Ezekiel repeats the same basic idea in different language. There, priests shall not take a “widow or divorcée” as a wife, but rather a b’tulah.

In both cases, it’s clear that b’tulah is the opposite of “widow,” “divorcée,” and “whore.” In other words, a b’tulah is a woman who has never had sex—that is, a virgin.

Other contexts support this interpretation.

Deuteronomy 22, starting with verse 13, contains laws about what happens if a man marries a woman, decides he doesn’t like her, and spreads rumors about the state in which he found her. In particular, according to the text, the case in question is if the man says that he didn’t find b’tulim. Clearly the word b’tulim is related to b’tulah, and most translations render the word as “virgin,” or “signs of virginity.” But we know that the similarity of form is not enough to demonstrate that b’tulim means almost the same thing as b’tulah.

Fortunately, Deuteronomy 22:19 makes the connection explicit. After a discussion about the woman’s parents and proof of b’tulim, the text explains what happens if it is demonstrated that the man made up the accusation about the woman. He is to be fined “because he spread rumors about a b’tulah of Israel.” So we know that a woman who has b’tulim is a b’tulah.

Deuteronomy 22:21 explains what happens if the man’s claim turns out to be true—that is, if she wasn’t really a b’tulah. She gets stoned to death “because she . . . was a whore.” Again we see that a whore cannot be a b’tulah. (As an aside, we might note that the punishment seems overly harsh to some, and there are those who think that it was never implemented. But the nature of the punishment doesn’t change how we interpret b’tulah and b’tulim here.)

Deuteronomy follows up with laws about an engaged b’tulah who has sex with a man. If the sex is consensual, they both get killed, while if she was raped only the rapist is killed. (Again, the details of the punishments don’t concern us now.) The passage is important for understanding what b’tulah means because we see a regulation about what happens if a b’tulah has sex. While just in this very limited context we might imagine a variety of options for what b’tulah means, the most obvious is “virgin.” If a virgin has sex, she is no longer a virgin.

Elsewhere we see the same concern about what happens if a b’tulah has sex. Exodus 22:15–16 (frequently numbered 16–17, because traditions about verse divisions sometimes differ), for example, describes what happens if a man has sex with an unengaged b’tulah. The man has to marry her and pay a dowry. However, if her father refuses to let her go, the man still must pay the dowry “of b’tulahs.” Once again, we see that the woman was worth the price of a b’tulah until she had sex.

Other contexts are less clear, but they do not contradict what we have seen. For example, Deuteronomy 32:25 juxtaposes bachur with b’tulah. Isaiah 62:5 uses the imagery of a bachur who marries a b’tulah. Assuming bachur means “young man” or even “(male) virgin,” we don’t know for sure what b’tulah means from either of these contexts, but neither do they present evidence that we are on the wrong track.

We see the word again at the beginning of I Kings, which starts with the story of the aged King David, who in his old age cannot keep warm. So a b’tulah is found to lie with him—though not have sex with him—to keep him warm. Again, we don’t know for sure from this passage that b’tulah means “virgin,” but it could.

In short, we see the word b’tulah used frequently in the Bible, and in every case it either might mean or it pretty clearly does mean “virgin.” So we conclude that that’s what the word means.

All of this brings us back to na’arah, which we saw in Genesis 24. There a b’tulah was a kind of na’arah. If b’tulah means “virgin,” we conclude that na’arah does not, because, it seems from Genesis 24:16, only some na’arahs are b’tulahs.

In Genesis 24:28, as part of the continuation of the same story, we once again find the word na’arah. This time the word is used not to describe Rebekkah but rather simply as a convenient way of referring to her. “And the na’arah ran off, and told” people what had happened.

The story in Genesis 24 seems to be written from two points of view: the limited point of the view of the servant and the omniscient point of view of the narrator. Sometimes the text tells us things as the servant would see them, yet other times we are given information that none of the characters could know.

In Genesis 24:14, the servant hopes to find a na’arah. That is all the text says. This is the limited servant-oriented view.

Then in 24:16 we get information that the servant does not have: The na’arah was a b’tulah. In addition to providing more confirmation that we are on the right track in translating b’tulah, we learn from this contrast that an observer (the servant, in this case) can tell by looking who is a na’arah but not who is a b’tulah. (The narrator knows, but the servant does not.)

This is why 24:28 uses the word na’arah. It seems akin to something like: “The servant saw a young woman . . . and the young woman ran off.”

We next find the word na’arah in Genesis 34:3, where it refers to Dinah. In Genesis 34:1 we learn that Dinah goes out “to see the daughters of the land” (KJV). Then in 34:2 Shechem has sex with her. (This is commonly assumed to be a case of rape, and this story is generally known as “the rape of Dinah.”) But in 34:3, Dinah is still a na’arah. This further confirms our observation that only some na’arahs are virgins—that is, b’tulahs.

Elsewhere, we find the word na’arah used in reference to female servants. In Esther 4:4, we read of Esther’s na’arahs and her male servants of some sort, perhaps eunuchs. Similarly, Proverbs 31:15 teaches that a good wife provides for her house and for her na’arahs, presumably female servants.

According to Exodus 2:5, Pharaoh’s daughter has na’arahs with her as she goes down to the Nile to wash.

And going back to Abraham’s servant finding Rebekkah, we read toward the end of the story in 24:61 that Rebekkah “and her na’arahs” followed the servant. So Rebekkah is a na’arah and she has na’arahs.

So now we’ve seen that na’arah is a woman of some sort, and that b’tulah means “virgin.” Knowing what these two words mean will help us understand alma.

We also find the word alma in the story about Abraham’s servant and Rebekkah. Rebekkah has a brother, Laban. Inside Laban’s house, Abraham’s servant tells Laban (and Rebekkah and their father, Bethuel) about his journey, repeating what the reader already knows. He explains that he hoped for a sign from God. In Genesis 24:14, when the text explains to the reader what Abraham’s servant did, the language we find is that the servant hopes for a na’arah. But in Genesis 24:43, when the servant explains to Rebekkah and her family what he did, the servant uses the word alma.

The two passages are not phrased identically, but they contain many of the same words, and they certainly are meant to convey the same idea. Genesis 24:15 and Genesis 25:44, which both continue Abraham’s servant’s hope for a sign, are even more similar.

As is frequently the case, two vastly different interpretations present themselves here. Either na’arah and alma are so similar that they are interchangeable, or they are different, and part of the cleverness of the text is the way Abraham’s servant phrases his hope one way in his own head and another when reporting to the family.

We find the word alma again in the story about Pharaoh’s daughter (Exodus 2:8), as she discovers the stranded baby Moses in the basket. Pharaoh’s daughter goes down to the Nile to wash. Her na’arahs, as we just saw, accompany her. In the meantime, Moses’ sister is watching to see what will happen to Moses. After Pharaoh’s daughter discovers Moses and concludes that this baby in a basket must be an abandoned Hebrew boy, Moses’ sister asks the daughter if she, the sister, should go get a Hebrew to nurse the child. Pharaoh’s daughter agrees. Then the text tells us that the alma—that is, Moses’ sister—goes to get Moses’ mother.

Once again, we see a connection between na’arah and alma, and once again the connection is unclear. Perhaps the two words mean the same thing, and the text uses alma just to make it clear that it wasn’t one of Pharaoh’s daughter’s na’arahs who went to get Moses’ mother. Or perhaps alma is similar to na’arah but different. For example, maybe alma is a more polite way of saying na’arah. If so, we would also understand why Abraham’s servant uses na’arah in his own mind but alma when speaking aloud of Rebekkah. But there are myriad other possible ways the words might be related, too.

We must note, however, that the passage in Exodus has nothing to do with sex or marriage or courtship. There is no reason to refer to Moses’ (at this point anonymous) sister as a “virgin.” In fact, it seems like the only reason not to just use “she” here is that, in the sentence, “she” could mean “the sister” or “Pharaoh’s daughter.” In other words, instead of “And Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, Go. And she went and called the child’s mother,” which might be confusing, the text gives us, “And Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, Go. And the alma went and called the child’s mother.” So one possibility is that, for reasons we haven’t uncovered, alma cannot be Pharaoh’s daughter here. On the other hand, the Bible frequently uses “he” and “she” when the referent is not entirely clear. In the end, then, we learn from Exodus 2:8 that our best guess for alma is some kind of young woman, perhaps with connotations of politeness or loftiness, but with no reference to virginity.

Proverbs 30 gives us another use of the word alma, though the context is poetic and obtuse. In Proverbs 30:18 we read, “Three things are too wonderful for me; four I do not understand” (NSRV). The phrases “too wonderful for me” and “I do not understand” are almost certainly in parallel, suggesting that “three” and “four” are also in parallel, even though they do not mean the same thing. Such, apparently, was the poetic effect, an effect repeated in Proverbs 30:21: “Under three things the earth trembles; under four it cannot bear up.” (We find the “three/ four” pattern elsewhere as well. The prophet Amos describes a litany of the sins committed by various peoples, using very similar language. In Amos 1:3, the prophet quotes God as refusing to hold back punishment on account of “three transgressions of Damascus, even four. . . .” Then three verses later, it’s on account of “three transgressions of Gaza, even four. . . .” After listing four other evil places, God finally promises to exact punishment on account of “three transgressions of Judah, even four . . .” and, after that, “three transgressions of Israel, even four. . . .” Amos’s message is typical of the prophets, who call Israel to task for behaving as badly as other nations.)

The four things alluded to in Proverbs 30:18 are listed in Proverbs 30:19: “The way of the eagle in the sky, the way of a snake on a rock, the way of a ship in the heart of the sea, and the way of a man with an alma.” We have to assume that the “way of a man with an alma” is sex, but beyond that the passage offers little more. Is this, like “the eagle in the sky,” the sort of repetitive behavior that is part of the natural course of things, in which case alma cannot possibly mean “virgin”? Probably.

But Proverbs 31:20 offers a fifth thing, seemingly out of place after a reference to “four things.” The fifth is “the way of an adulterous woman. . . .” Some people see this fifth thing as part of the list, while others disagree. If it is part of the list, we again have two options. Either it is meant to clarify the fourth list item—in which case the “way of a man with an alma” would be like the way of an adulterous woman—or it is meant to augment the fourth item. Whatever the case, the section is complicated enough and vague enough that with very little twisting it can point in almost any direction.

So Proverbs 31, while interesting, doesn’t help us much. Still, people who have an agenda frequently refer to Proverbs 31, confusing consistency with proof. Proverbs 31 is consistent with a lot of meanings for alma. But that doesn’t prove what alma means.

Psalm 68:26 gives us a different look at almas. Psalm 68:25 sets the stage by introducing the concept of God’s processions, which the next line describes as “singers in front, players [of music] behind, among almas drumming.” Debate rages over the exact meanings of the words we translate as “sing,” “play,” and “drum,” but consensus is universal that we have three types of music-making going on here. One kind involves almas doing something. (As yet another example of how English has changed and how minor differences in phrasing can alter the meaning of a passage, it is interesting to note that the KJV translates the last bit as “[damsels] playing with timbrels.” In modern English, if they are playing timbrels they are making music, while if they are playing with timbrels, they are just having fun.)

If almas are to be involved in God’s procession, at the very least we know that alma is not a derogatory word. From Psalm 68:26, we suspect that it may be a fancy word or even specifically a musical one. (Psalm 46:1 also connects almas with music in a way that is so vague that most translators don’t translate the word. It’s hard to know for sure, but I Chronicles 15:20 may do so, too.)

Finally, we have Song of Songs. The word alma appears twice, once in 1:3 and once in 6:8.

The first time, we learn that the hero is anointed and “therefore almas love” him. The second time, the text tells us that there are “sixty queens, eighty concubines, and countless almas,” but only one heroine who is the hero’s “dove . . . whom daughters see and delight, queens and concubines praise.”

While Song of Songs doesn’t tell us precisely what alma means, it confirms what we already know and provides information about what the word doesn’t mean, because we see a very clear context for alma here. The almas are like queens and, crucially, like concubines. They are women who have had sex. That doesn’t mean alma means “woman who has had sex,” but quite clearly the word doesn’t mean “virgin.”

Indeed, we have seen no reason in any of the examples to think that alma means the same thing as b’tulah, and we saw that b’tulah means “virgin.” Rather, alma means something like na’arah, and only some na’arahs are b’tulahs. We also suspect that alma is a poetic word. Perhaps the word implies musicality, or maybe music is just one way a na’arah becomes an alma. There are lots of possibilities, and, as usual, we have no way to know the details of the nuances for sure. But one thing is clear. We have no evidence to suggest that alma means “virgin” and lots of evidence to suggest that it does not.

Why, then, does the King James Version, paving the way for future translations, sometimes translate alma precisely as “virgin”?

To find an answer, we turn to King Ptolemy II of Egypt, whose reign lasted from 287 to 247 B.C. According to legend, in the middle of the third century B.C., King Ptolemy commissioned seventy-two Israelites—six from each of the twelve tribes—quizzing them with seventy-two questions and asking them to translate the Five Books of Moses from Hebrew into Greek. After seventy-two days, the seventy-two Israelites, working independently and in isolation, all produced exactly the same Greek text, proving that it was a God-inspired translation.

As it happens, it was a God-awful translation, as we will soon see (in particular on page 217). In addition to the text of the translation itself, though, there are aspects of the legend that call its veracity into doubt. For example, the story comes from a letter sent from someone who calls himself Aristeas and claims to be a Greek pagan. Yet from the content of the letter (which we know about from the Roman writer Josephus), it is almost certain that the writer was Jewish. Also, the twelve tribes had been disbanded centuries earlier.

Scholars now believe that the translation dates from the third century B. C. onward, and that it comes from Egypt, probably Alexandria. The first versions of the Septuagint included only the Five Books of Moses, and other parts of the Bible were translated later. (Even though scholars no longer believe the legend about the seventy-two people, questions, and days, the version still goes by the name “Septuagint,” which is Greek for “seventy.” In a bit of academic cleverness, scholars frequently abbreviate this Greek name with the Roman numeral “LXX.”)

Because of the centrality of Greek in the Church, and because this is one of the oldest translations of the Bible, the Septuagint is frequently consulted in matters concerning translation and, more broadly, the text of the Bible.

Deuteronomy 31:1 starts with the Hebrew word vayelech—that is, “he went.” The sentence is “Moses went [vayelech] and spoke these words to all of Israel.” It appears after one of Moses’ finest speeches, in which he calls on heaven and earth to witness, exhorting the people of Israel to choose life over death.

The Hebrew phrasing seems odd. Where, exactly, was Moses going? Why does it say “Moses went”? As it happens, we have an English expression: “go and . . .” For example, “You had to go and open your big mouth again. . . .” In English, the verb here doesn’t have anything to do with actually going anywhere. By contrast, Biblical Hebrew had no such expression. The English expression masks the oddity of the original Hebrew.

The Septuagint, however, has a completely different translation here. The Septuagint reads, “Moses finished speaking these words. . . .” That would make a lot more sense as a segue. First Moses speaks the monumental words of his speech, and then, when he had finished speaking the words, the next thing happens.

The Hebrew for “he went” consists of four letters: vav-yud-lamed-kaf, or, in transliteration, V-Y-L-K. The verb for “he finished,” however, is V-Y-K-L. And, in fact, it is V-Y-K-L that appears in the Dead Sea Scrolls where the Hebrew Bible has V-Y-L-K. In other words, this looks like what scholars call haplography (“wrong writing”) and what everyone else calls a typo.

It looks like the original text read V-Y-K-L, “he finished,” and somewhere along the line a scribe mixed up two letters. The mix-up happened, it would seem, after the Dead Sea Scrolls were written sometime after the year 200 B.C., and after the Septuagint was written. This case and others like it prompt people to look to the Septuagint as at least an aid in understanding the Hebrew.

There are, of course, problems with that strategy. We don’t always know what the Greek meant. And we must allow for the real possibility that the authors of the Septuagint weren’t very good translators. Nonetheless, it’s often at least interesting to know how the Septuagint renders a particular Hebrew phrase.

And here we get to the source of the problem. The Septuagint is fairly consistent in using the Greek word parthenos for the Hebrew b’tulah. The word b’tulah and the related b’tulim appear dozens of times in the Bible, and in almost each case the Greek translation is parthenos. And of the times where the Greek is another word, there is usually a good reason.

Sometimes the reason is that the Greek text is just different from the Hebrew, so the Greek doesn’t have the word at all. (In addition to cases of haplography and other errors, the Septuagint and the Bible that we use differ because they reflect different traditions.) For example, Esther 2:19 in the Hebrew Bible reads, “And when the virgins were gathered together the second time, then Mordecai sat in the king’s gate” (KJV). But the Septuagint is shorter. It just says, “But Mardochaeus served in the palace.” The Septuagint version of Esther frequently differs from the Hebrew text, so we are not surprised at this divergence here. We also find a few instances in Jeremiah where the Greek differs enough from the Hebrew text that it doesn’t contain the word b’tulah at all.

Other times, as in Ezekiel 23:3, the Greek uses a verbal related to parthenos (sort of like parthenosized) where the Hebrew has an expression. Either way, the point is probably “become a nonvirgin.” Five verses later, the Greek has “sexual immorality” instead of “virgin” for the same reason.

Taking into account some additional, complicated reasons why the Greek might differ, we end up with only a few cases where the Hebrew b’tulah seems like it should be parthenos but isn’t.

So we are on very solid ground in deducing the widely accepted fact that parthenos means “virgin” and is the Greek translation of b’tulah. (Because we have other evidence from outside the Septuagint, we have other ways of knowing what parthenos means. So this is further evidence that we are correct in our translation of b’tulah, though the additional evidence here is based on the dubious Septuagint translation, so it’s not as solid as it would be if we had more faith in the fidelity of that translation.)

The Septuagint had more trouble finding a translation for alma. In Genesis 24:43, the Greek is thygatir, “daughter.” In Exodus 2:8, Song of Songs, and Psalm 68, the Greek is neanis, which means “young girl” or something like it. (In Psalm 46, where we have noted that the reference to almas was difficult to interpret, the Greek assumes that the word is not alamot, the Hebrew plural of alma, but rather alamut, which means “secret.” The Septuagint may be more accurate here. If so, the Psalm would begin, “. . . a Psalm about secret things.”)

We perhaps shouldn’t be surprised that the translators of the Septuagint didn’t know exactly how to translate alma. The word is uncommon and, as we just saw, it’s not easy to figure out exactly what it means. Probably it was a word that English doesn’t have and that Greek didn’t have, either.

So there are probably a handful of ways to translate alma that are fine—or, at least, not terrible. Anything that roughly means “young woman” is probably pretty good.

Unfortunately for us, in most cases in antiquity, “virgin” was a word that also meant “young woman.” Whereas today the words have very different meanings, in antiquity using “virgin” for “young woman” was exactly the same as using “coed” for “woman” or “middle schooler” for “young woman.” As we have seen, ages can be used for roles and vice versa.

In a society where twelve-year-olds married, there was very little room for nonvirgin young women. Certainly some girls must have married late (or not at all). Some must have remained virgins past their early teens. And we must allow for the unfortunate possibility that some girls lost their virginity at a much younger age.

This ancient situation with age and sex mirrors the modern one regarding age and school. And because ages and roles are usually interchangeable, there was usually no reason not to use “virgin”—that is, parthenos—in translating a word that literally meant “young woman.” It was like using “high schooler” for “teenager.”

This is why the Septuagint uses parthenos not only for b’tulah but for other words as well. In Genesis 24:14, the Septuagint renders na’arah as parthenos. It was a translation error, but not a serious one. Rebekkah was probably both a “young woman” and a “virgin.” But we see the consequences of the error two verses later, where the Septuagint uses parthenos both for na’arah and for b’tulah, yielding the fairly silly translation, “the virgin was . . . a virgin.” (It should be, “the young woman was . . . a virgin.”)

Any careful translator would have noticed the error at this point. While there are frequently a variety of equally good choices for translating a particular word, when one language has two different words, it is almost always wrong to translate them as the same word. Doing so destroys the effect of having two words in the first place. The Greek in Genesis 24:16 is a classic example of what can go wrong. But rather than find another word for na’arah—neanis (“young girl”), for example, or even thygatir (“daughter”)—the Septuagint blindly translates na’arah as parthenos, its authors perhaps not even noticing the inconsistency of using parthenos for na’arah right next to parthenos for b’tulah.

This is actually typical of the Septuagint. While it has value, particularly when it reflects a text that seems to differ from what we expect, the Septuagint is not by and large a very good translation. The authors of the Septuagint seem to have known very little about translating. They had not read Chapters 2 and 3 of this book, or any of the other modern books that explain translation. Rather, they mechanically translated the Hebrew, sometimes word by word, into Greek. Frequently, the only question the translators seem to have asked themselves is how to say a particular Hebrew word in Greek. They didn’t ask if it was the right word in context. This is what led to the awful rendering of Genesis 24:16.

This is also what led to the awful rendering of Isaiah 7:14. The Hebrew reads: “The alma” shall conceive. (That’s a rough translation. We still haven’t gotten to what hara, “shall conceive,” means. But we will.) We know that alma means something like “young woman,” and we know that it does not mean “virgin.” The Septuagint, however—following its usual pattern of simply finding a word that’s good enough, regardless of context—translates alma as parthenos here. In other contexts, it’s not a terrible choice for alma. After all, as we have seen, “young women” and “virgin” meant almost the same thing.

But, of course, there is one time when they absolutely did not, and do not, mean the same thing. And that is when sex is involved. Or, to look at the situation another way, “virgin” implies “young woman”—because it was hard for a woman to get past her early teen years without having sex—but “young woman” does not imply “virgin.” There was no reason a woman couldn’t have sex before she might otherwise be expected to. A modern parallel, again, would be using “high schooler” for “teenager.” Usually it wouldn’t be a problem. But the difference becomes relevant when schooling is involved, so “the high schooler had no education” is not at all the same thing as “the teenager had no education,” even though both “high schooler” and “teenager” work equally well in many other contexts. Parthenos for alma is similar.

Based on this sloppy and ultimately faulty translation, the KJV, too, translates alma as “virgin,” giving us the famous translation: “Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel.”

But this is a mistake. While the woman may have been a virgin, the text does not say “virgin.” It says “young woman.”

The authors of the KJV must have known better, too. In Exodus 2:8, they use “maid” for alma. In Psalm 68, “damsel.” In Song of Songs, they again use “virgin.” In Genesis 24:14 and 24:16, they use “damsel” for na’arah and “virgin” for b’tulah. But again they revert to “virgin” in Genesis 24:43.

In other words, when alma appeared by itself, the authors of the KJV seemed perfectly happy with “maid,” “damsel,” or “virgin.” Their reasoning may have been that, in the days of the translation, “virgin” was used not just in its modern sense but also to mean any young woman. So the English of the KJV was similar to the Greek of the Septuagint. “Virgin” (or parthenos) meant what it does today, but also referred to any young woman. Unlike the authors of the Septuagint, the authors of the KJV were usually careful to avoid nonsense like “the virgin was . . . a virgin.” They took context into account.

But in the crucial case of Isaiah 7:14, apparently, they couldn’t resist mucking with the translation to make it mean what they wanted it to for theological reasons. They wanted Isaiah to prophesy the birth of Christ.

Young Men and Women

It turns out that both alma and na’arah have masculine counterparts, namely, alam and na’ar. (The connection between na’ar and na’arah is easier to see for those who don’t know the details of Biblical grammar, but the connection between alam and alma is, in fact, just as clear. It’s like melech and malka for “king” and “queen.”)

It is tempting to try to analyze the words alam and na’ar to help us figure out what alma and na’arah mean, but it would be a mistake, because we frequently find that gendered words mean different things for men and women. Even though na’arah is the feminine form of na’ar, the two words might mean different things. The same problem applies to alam and alma.

As an example, we can compare the English words “master” and “mistress.” While they may have once had similar meanings, they certainly don’t anymore. “Mistress,” as we saw in Chapter 6, is generally a term for a woman in an unmarried relationship. More importantly, “mistress” in this context doesn’t imply any power—and, in fact, suggests a lack of power. The man has power over the mistress, not the other way around. By contrast, “master” is, in general, a position of power, or a state of high competency. A “master storyteller,” for example, is a storyteller who’s very good at storytelling. But a woman isn’t a “mistress storyteller.”

And even if we wanted to use alam to help us understand alma, the word appears only twice in the Bible. Both times it appears to mean “young man,” but it’s hard to know for sure. The KJV translates the word once as “young man” (in I Samuel 20:22) and once as the otherwise unattested “stripling” (in I Samuel 17:56), a rare word that means “young man.”

The Youth

It turns out that Isaiah 7:14 doesn’t just talk about “an alma” but rather “the alma.” The difference between “a” and “the” is that “the” is usually used only when the reader can be expected to know not only what the word means but also what it refers to.

As an example of “a” versus “the” in English, we might note that this sentence begins with “an example,” because the reader doesn’t yet know what the example refers to. But the third time “example” is used in the sentence, it is “the example,” referring to the example that was introduced in the first part of the sentence.

But the matter is tricky.

Another example of “the” in English might distinguish “cat” from “the cat.” “A cat is a feline creature that thinks it runs the world” refers to any cat, in general, not to a particular one. On the other hand, “The cat in my house knows that it runs the world” refers to a specific cat, and the reader is expected to know which one. In this case, it’s the one “in my house.”

But even so, a researcher might note that “the wolf is returning to Yellowstone Park,” which doesn’t mean that a particular wolf has been making a long trek from somewhere and is finally near the end of its journey. Rather, it means almost the same thing as “wolves are returning. . . .”

In other languages, too—as we now expect—we find similar complexity and only a partial match to English. Some languages like Portuguese put “the” before names (for example, “The Chris has a cat”). Others don’t even have words for “the,” and use syntax where English uses vocabulary.

So in Isaiah when we read “the alma,” we have to be careful. It may refer to a specific alma, but, if so, the text doesn’t tell us who she is. (In Exodus 2:8, by contrast, we see “the alma” only after the preceding verses tell us about Moses’ sister.) Or the use of “the” may refer to a general phenomenon in Isaiah, as if to say the sign is that “almas will get pregnant and give birth.” Sometimes the Bible reads “the God” (ha-elohim) and sometimes just “God” (elohim), but the point is always the same, and most translators know better than to mimic the Hebrew word for “the.” This may be a similar situation. Or it may even reflect poetic license.

One thing we know. We cannot blindly assume that “the” in Hebrew should be “the” in English.

Youth in General

We have a few loose ends to address, including where the notion of “young” comes into play and, finally, a short discussion of the Hebrew hara, wrongly translated as “shall conceive” in the KJV. We’ll start by returning to alma and na’arah.

We have translated those two words so far as “young woman.” It’s clear that they refer to women or girls of some age, but where does the notion of “young” come from?

Here we have to be particularly careful, too, because “young” and “old” mean different things in different contexts. A young woman is older than an old girl, for example (just like a big mouse is smaller than a small elephant). For that matter, a ninety-five-year-old might call her fifty-one-year-old granddaughter a “young woman,” while that woman’s children probably would not. Ten-year-old children sometimes talk about “when they were young,” to the amusement of adults who think the ten-year-olds still are. And when the average life expectancy was forty, a forty-five-year-old was, generally speaking, pretty old. She no longer is.

So our real question is twofold: How old, and in what stage of life, were these na’arahs and almas? And do we have a way to express that in English?

We don’t have any direct information to help us answer the first question. We certainly don’t know how old they were. We do know that na’arah and alma include women of marriageable age, which, back then, was roughly twelve and onward.

We can guess that na’arah did not refer to the elderly, though, based on unreliable evidence from the word na’ar. We just saw that we have to be careful using a masculine word to determine what a feminine word means; with this in mind, we note that the phrase “from na’ar to old” appears in the Bible, at least suggesting that na’ar, and perhaps na’arah, have something to do with youth.

Similarly, we can guess that na’arah was not limited to older children or younger adults. In Exodus 2:6, Moses, having just been discovered by Pharaoh’s daughter and about to get a wet nurse, is called a “crying na’ar.” (The KJV uses “babe” for na’ar here.) If na’ar meant “any young (male) person,” we might guess that na’arah meant any young female person, from infancy up to some age that we cannot determine.

At first glance, this might seem troubling. If na’arah can mean an infant, why would Abraham’s servant have been looking for a na’arah? The answer, of course, is that na’arah is broader than just “infant,” just as it is broader than just “virgin” (or “nonvirgin”). The word na’arah seems to be a very general term. In colloquial English, we use the word “girl” for this. A “girl” is a baby, a child, a date, a secretary, etc., though some populations frown on using “girl” in some of these contexts. (And yet again, we see a difference between masculine and feminine words. A boss might refer to a female secretary as “my girl,” but usually not to a male secretary as “my boy.”)

Information about alma is even more difficult to discover because the word is used so rarely. We know that an alma can be at least some of the ages of a na’arah, so we can probably exclude old women, but we can’t even be sure of that. Our best clue is the way Abraham’s servant uses the word in the presence of the people he wants to impress. So alma probably doesn’t mean “hag” or any other insulting term.

But even though we don’t have evidence from the text, we have anthropological evidence about the culture. Once we remember that all of these people getting married and having children were in their teens, we realize that the most accurate description of na’arah is “teenager,” or simply “teen.” Both are the wrong translation, but before looking at why, another look at the word “teenager” is helpful, because it reemphasizes an important point about words and how they work.

A “teenager” can be a boy or a girl (or, perhaps, a man or a woman). But a “teenager who gets pregnant” must be a woman in English. In other words, “teenager” is usually ambiguous as to gender, but context sometimes renders it specific. In Modern Hebrew, there are two words for “teenager”—one masculine, one feminine. Context tells us which Hebrew word to use for the English.

Similarly, the words we have seen—alma and na’arah— are sometimes ambiguous, but context tells us which words to use for them in English.

And an alma can be—in fact, usually was—a teenager. Still, we don’t want to refer to a “pregnant teenager” in our translation because a pregnant alma was a common occurrence in antiquity. The age of an alma was the usual age for childbirth, and almas were expected to get pregnant. The same is not true of “teenager.” We frequently use different words to describe the same phenomenon when we wish to make our attitudes about it clear. (Earlier, we noted that a “teen” could be a “girl” or a “woman,” but once she’s pregnant, we prefer “woman.”) More importantly, “teen,” while chronologically accurate, is completely misleading because, as we noted at the beginning of the chapter, there were no teens in antiquity, at least not as we generally use the word. “Teen” most naturally refers to a stage of life, and that stage of life wasn’t part of antiquity.

So we make a list of our clues about the word alma. Though it was compatible with “virgin,” there’s no reason to think that it meant that. It was the natural age for childbirth. And it was, at the very least, not a derogatory word. We actually have a word for that in English: “woman.”

We don’t use “young woman,” because in English that implies a woman younger than one might expect, or, at least, at the young end of some spectrum. While an alma was chronologically young, she was older than a child and ready to bear children.

So we’ve translated alma: “woman.” To translate the line, we have to take a quick look at hara.

Pregnant

Fortunately, unlike alma, hara is easy to decipher. The word occurs more than a dozen times in the Bible, and every single time it means “pregnant.”

For example, in Genesis 16:11, Hagar is told, “You are hara, and you will give birth to a son.” The KJV translates it as “with child.” The NRSV prefers “You have conceived.” And the NAB gets it right with “You are now pregnant.”

Talking about pregnancy is taboo in some circles, so new words to describe pregnancy keep popping up in the language. Once “with child” was a common expression. Then that became too common, so people started using “pregnant,” Latin for “expecting,” as in “expecting a child.” Then that became too common, and now some people prefer the English “expecting.” In yet another move away from talking about the woman and her womb and so forth, many people use “pregnant” and “expecting” for both members of a couple, so in some dialects it’s not just the woman who’s “pregnant” or “expecting,” it’s the couple.

We have no reason to think that a similar taboo existed in the Bible and we have no reason to use a euphemism in translating hara. If the point is “You are with child,” the right English is “You are pregnant.”

Genesis 38:24– 25 is equally clear. Tamar gets pregnant (after “playing the whore”). She is hara.

Exodus 21:22 is also clear. If someone hits a woman who is hara and she loses her baby, the off ender must pay a fine.

Accordingly, “the alma is hara” can only mean a woman who is pregnant.

So Isaiah 7:14 reads, “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. A pregnant woman will give birth to a son, and call him Immanuel.” Because the name “Immanuel” means “God is with us,” so we might equally translate, “. . . call him Godiswithus.”

At first glance, one might wonder—and people have wondered, vocally and vehemently—what kind of sign “a pregnant woman” giving birth might be. After all, they (wrongly) argue, only a “virgin” giving birth would be worthy of “sign”-ship. That would be a fitting introduction for “Immanuel,” for God being with us. But just any woman of childbearing age bearing a child would not properly set the stage.

They are completely wrong, and they have missed the entire point.

The sign here is a reminder that extraordinary things can come out of the ordinary. That is Isaiah’s point. If a virgin gave birth, we would hardly need the text to tell us how amazing that was. Surely we would know it on our own. But, Isaiah is apparently concerned, some people might forget that signs come from daily events, too; that Immanuel can come from a perfectly plain woman of childbearing age; that life itself can be miraculous.

When we look carefully at Isaiah, we see the sign hidden in plain sight and we know that God is with us.