There was that blissful hour every afternoon when residents of the Alley of the Pretty One would venture out to their balconies, sit back, and savor their café turc, and the narrow little lane turned festive and joyous. Families put the difficulties of the day behind them. Friends and even strangers strolling in the area were entreated to stop by. Everywhere, there were cries of Ahlan musahlan, the effusive Arabic greeting that manages to say hello and welcome and please come join us in two words.

The ritual of the late afternoon Turkish coffee was sacred throughout Sakakini, a cozy neighborhood where many of Cairo’s Jews lived in small buildings they shared peaceably with their Muslim and Coptic neighbors. Sakakini’s streets were lined with four- or five-story walk-ups; the taller, more stately structures, a few with elevators, could only be found on the adjoining boulevards such as Malaka Nazli. Finally, there were the little serpentine alleyways, dozens and dozens of them, where the residences were ever so humble, made of ancient stone and typically only a couple of stories high.

There, the roads were dusty and unpaved, and even one car could barely get through.

Haret el-Helwa, the Alley of the Pretty One, where my mother, Edith, lived with my grandmother Alexandra, was longer than most alleyways and a bit more distinguished as it had its own mosque, smack in the middle. Five times a day residents could hear the imam’s stirring call to prayer, “Allahu akbar.”

Every apartment had a balcony, and in those days when even a ceiling fan was a luxury, it became an essential gathering place come dusk, when the intense heat of Cairo finally broke and a wonderfully refreshing breeze would drift in from the Sahara.

That is when the balconies would fill up with people—grandparents, rambunctious children, tired housewives—and they’d bring out serving tables crammed with snacks to nibble on, à grignoter, such as freshly peeled cucumbers, roasted pistachios, slices of mandarin oranges, or sticks of sugar cane that everyone young and old loved because they were so juicy and delicious. Occupying the place of honor was the tanaka, the little copper pot with the long handle filled with steaming Turkish coffee, sweetened for good luck.

It was a ritual enjoyed by all. The only difference was that the Jews tended to speak French among themselves, whereas Muslims conversed mostly in Arabic and the Copts a mixture of the two. But it was a sign of how well everyone got along that in addition to the mosque there were at least four major synagogues within a few blocks.

Whenever a cool breeze would blow in, you could hear the murmurs of relief. “Enfin, de la tarawa”—finally, some fresh air—someone would cry in that mixture of French and Arabic so many favored in this culture that managed to be both European and Middle Eastern.

Most of the alley’s residents were content simply to be outside, enjoying the street life. Even in the evening, vendors were still on the prowl, and you could count on seeing le marchand de robabekiah, the merchant of used wares, pushing his little cart filled with the oddest odds and ends—a broken, naked doll, a rusty cooking pot, a cardboard box. He’d come by chanting “Bekiah, bekiah” (“Old junk, old junk”), hopeful even at this late hour to make a deal of a piaster or two that would redeem his day and make his hard labors walking in the heat worthwhile.

My grandmother Alexandra, who was fluent in Italian, would shake her head at their ignorance, the fact that they didn’t even realize they were citing an Italian phrase—roba vecchia, old clothes—they had appropriated and made their own and turned into a colloquial Arabic expression.

Alexandra and Edith were fixtures on their balcony, joined occasionally by Félix, Mom’s younger brother. They lived on the ground floor—the least expensive dwelling in any building—and even paying for that was a struggle, and most of the neighbors knew it because everyone knew everyone else’s business.

The apartment was small and dark—not much sun ever penetrated the narrow alleyway—and sparsely furnished. The living room in the front had only le canapé, a small couch that doubled as a bed for Félix. My mother and grandmother shared the bedroom in the back. And then there was Alexandra’s piano, the most essential object in the house and the most incongruent, which she played less and less as she grew older.

Edith was the Belle of the Alleyway, and some liked to say she had given the alley its name. That was fanciful, of course: Haret el-Helwa had preceded the young girl by decades if not centuries. Still, like a lovely fable, a myth that springs out of thin air and takes hold, the story was repeated and spread.

Her beauty didn’t give her too many advantages. Edith lacked both male and female companions, except for my grandmother who wouldn’t let her out of her sight. Alexandra was prone to melancholy, and the only person who could reassure her and keep her calm was her daughter. The two were constantly together—to be separated even for a few hours of a day was unbearable, certainly to Alexandra.

They made a striking pair. Alexandra, small, bent over, pencil thin from years of barely eating, was always slightly unkempt, her gray hair awkwardly pushed back in a loose chignon, her clothes worn to the point of shabbiness, the buttons of her sweater missing or slightly askew, her stockings drooping or with holes in them, her shoes frayed and dusty, with a book or magazine tucked under her arm. Edith, on the other hand, dressed impeccably, in fitted skirts and delicate blouses and high heels. With her perfect posture, she actually appeared taller than her five-foot frame, and she had an innate sense of style that made her stand out among the women of the neighborhood.

Alexandra took immense pleasure in her daughter’s beauty, and she loved to say that Edith couldn’t walk down a street in Cairo, even in the fashionable quarters en ville (downtown), without drawing stares.

In 1937, shortly after her fifteenth birthday, my mother landed her first job—a position as a schoolteacher at Le Sebil, the communal Jewish school that was heavily supported by the Cattaui family. It was a remarkable achievement, not simply because of her youth. Teachers were a kind of aristocracy, and they were treated with absolute deference not only by schoolchildren but by other adults. Women who entered the profession were held in especially high regard in an era when girls were pushed to do little more than get married as young as possible.

And that is exactly what most of them did.

Despite the flowering feminist movement unleashed the prior decade by Hoda Shaarawi, Cairo in the 1930s didn’t encourage a woman to get an education, and girls rarely remained in school beyond the age of twelve or thirteen. Many of the young Jewish girls were snapped up by the local couturieres, or seamstresses, to work as apprentices and learn the craft for a few years before settling down.

Those who were pretty and worldly found slightly better jobs at the big opulent department stores. Cicurel, the grandest of them all, placed a high premium on beauty and tended to hire strikingly attractive young Levantine girls barely in their teens for their sales force. They were paid both a salary and a commission, and the more aggressive among them did quite well.

Edith could never see herself as a shopgirl, nor would Alexandra have allowed it. Instead, she stayed in school an extra couple of years until she earned the coveted brevet, a kind of high school degree, and along with it, a license that allowed her to teach. Few women in the community ever went as far as obtaining the brevet, and Mom considered it her single most precious possession on earth. She didn’t let it out of her sight and never would. Dated May 1937, it was issued by the Academie de Paris, the august body in Paris that set educational standards for schools all over France. The Academie was also in charge of overseeing French schools abroad that followed their curriculum. “Mademoiselle Matalon has been judged worthy of receiving a Brevet to teach elementary school,” the large brown document stated.

There she was, working in the same school the pasha’s wife loved to patronize. My mother had noticed her, of course, as she swept into the school to do her good works in the cafeteria or with the needy students. But she was too shy to approach her and could only marvel at her from afar, admiring both her elegance and the tenderness she lavished on the children.

Situated in a massive brick building, Le Sebil had classes of forty students and more. In addition to the Cattauis, other moneyed families also helped—the Jews who lived on the other side of Cairo—in the gated villas of Heliopolis and Zamalek and Garden City and Maadi. While these didn’t necessarily mix with the Jews of Sakakini or the Old Ghetto, they were committed to making sure the less fortunate in the community had enough food to eat while their children received a solid education.

Academic standards were fairly rigorous, but life at the Sebil was grim. My mother was shaken by the extent of the poverty among the children. Many came to class in the morning hungry, and she was painfully reminded of herself as a little girl, foraging for food with Alexandra. “Ce sont des pauvres hères,” she’d tell her mother sorrowfully; They are all these poor ragamuffins.

In the absence of a government welfare system, the Jews of Egypt tried to take care of their own with a far-flung network of charitable funds set up to help every needy group imaginable—orphans, widows, the sick, the aged, the destitute, the insane. There was even a pot of money for single women in danger of never marrying because their families couldn’t afford a dowry. It was a favorite cause of the pasha’s wife, for whom every bride was Indji, every dowry she subsidized was one she would have arranged for her dead daughter.

In Edith’s case, her slender means didn’t seem to matter. Matchmakers were already circling; they had approached my grandmother about potential suitors anxious for her daughter’s hand. These were said to be so smitten that one or two were prepared to forgo la dotte—the all-important dowry.

Alexandra wouldn’t hear of it. She made it clear she wasn’t going to turn her daughter over to le premier chien coiffé, the first well-groomed dog, as the French liked to say, the first rake who came along. She was sure that Edith could make a dazzling match someday, and she was still so young they could afford to wait. Besides, it would be so hard living apart—now that her daughter went to work every morning, the day somehow felt longer, more difficult to navigate.

Edith left early for her teaching duties at the Sebil, and Alexandra was left to fend for herself.

My grandmother was so terrified of being alone she’d simply remain on the balcony and wait for Edith to come home. She’d be fixing herself coffee, boiling the water with several spoons of the thick Turkish blend; and for nourishment she nibbled on some khak, the salty, ring-shaped biscuits sprinkled with sesame. She was also constantly lighting up—one cigarette after another she bought from urchins on the street. These were young boys who made a living gathering discarded cigarette butts that they turned over to slightly older youths who specialized in removing any precious leftover tobacco from the stubs, which they’d then recycle. There was a whole industry in Egypt rolling these primitive, cheap cigarettes that were sold loose on the streets, and Alexandra was a devoted customer.

She’d plunge into some novel her daughter had managed to filch for her because in the same way that my grandmother was always smoking one cigarette after another, and drinking one cup of coffee after another, she couldn’t survive without reading one book after the other.

When Edith finally came home, the two women would start the evening side by side on the balcony, sipping coffee and chatting. Later, they’d take a stroll over to Sakakini Palace around the corner. Years after it was built, it was still an object of wonder, this fantastical mansion with its domes and golden statuettes and turrets. There it stood in the middle of a vast traffic circle from which eight different streets fanned out, like spokes of a wheel. The palace not only anchored the neighborhood, but gave it a certain cachet and even its name.

In their evening walks, Alexandra, arm in arm with Edith, would cross over to the palace. Often, they continued their stroll and went to pay a call on Alexandra’s stepdaughter, Rosée, who lived nearby. They could sit with her and talk for hours even as she plied them with coffee and food. On a hopeless quest to persuade both women to eat, she’d serve one dish after another. Sometimes, Edouard—Edith’s favorite uncle—would be there. Edouard was a dashing fellow who had clawed his way out of poverty and now lived downtown, where he thrived as a pharmaceutical salesman. He had a special fondness for Edith, and so when he was there, the atmosphere was especially joyful.

Later, if they had a bit of change, my grandmother and my mom would catch a double feature at the cinéma en plein air, the small outdoor movie theater near Sakakini Palace whose nightly show started promptly at 9:00 P.M. The cinema offered comfortable bamboo chairs where every evening, spectators could lean back and enjoy the latest Hollywood movie while eating a sesame roll with cheese from the vendors who walked up and down the aisles; and my grandmother, who loved the movies almost as much as books, was finally at peace.

Typically, the shows lasted till midnight, and when they came out, the neighborhood was still awake and alive, and they could buy a bag of roasted chestnuts from one of the vendors stationed outside the cinema and nibble on them as they strolled home.

Those evening hours—the café turc with Edith on the balcony, the pleasant exchanges with neighbors, the little constitutional walks, the occasional double feature—were so precious to Alexandra. It was hard to be a woman on your own in Egypt even if you had relatives or friends. People always looked down on you, felt sorry for you, avoided you.

Edith was her life. Alexandra knew that she could rely only on her daughter who was so much older than her years. Edith the diligent one, Edith the studious one, Edith the pretty one, Edith the dark-haired, doe-eyed hope of the family, the one who would rebuild their lost hearth.

How they had survived after her husband abandoned them, Alexandra was never sure. The recent years in the little ground-floor apartment were the good times. In the late 1920s, when Edith and Félix were children, Alexandra’s husband, Isaac, had squandered what money they had, then left the family to fend for themselves. My aristocratic grandmother—cosseted and spoiled as the child of wealthy parents—hadn’t known how to cope.

Even as she watched Alexandra unravel, young Edith took charge and looked after the three of them, preparing small elemental meals with the bits of food she could gather, keeping the house clean, caring for Félix. The passionate attachment between mother and daughter dated back to that period, when Alexandra had only the most tenuous grasp on reality and Edith was trying to save her with all the might and determination and ferocity that a strong-willed little girl can summon. She was forced to grow up fast, to forgo any childhood pleasures.

To forgo any childhood, period.

They had practically starved, and they couldn’t afford any rents at all, even in the dustiest alleyway, even in the Haret-el-Yahood, the ancient Jewish ghetto where the desperately poor lived in the equivalent of rabbit warrens. So off they went to Alexandria, where my grandmother still had relatives who remembered her, who loved her, who could be counted on to give them a place to stay.

For a time the three of them—Alexandra, Edith, and young Félix—were nomads seeking refuge with various aunts or cousins. Their favorite, Tante Farida, Alexandra’s half sister, took them in for weeks at a stretch. She treated Edith like a daughter and gave the family their own room. There were other stray cousins with whom they could dine so they were assured at least a square meal or two each day. But there were no offers of permanent shelter, and besides, my grandmother would never have agreed. She had trained Edith even as a child not to convey how desperate they were, and above all not to reveal that they were hungry.

Once a month they’d go off together on the most humiliating mission of all: to collect money from Alexandra’s hopelessly cold relatives, those members of the famed Dana family who were almost obscenely prosperous and lived in villas and stylish apartments between Alexandria and Cairo.

They took turns giving my grandmother one Egyptian pound for her troubles—une livre par mois—that was her allowance. One pound. It was supposed to cover her expenses raising the children, feeding them, and keeping a roof over their heads.

Alexandra would pocket the one-pound note, take Edith by the hand, and return to wherever they were staying or travel back to Cairo. There, she would descend on other relatives, like her brother Edgar who also lived in Sakakini, and make an appeal. My grandmother was always so shy and apprehensive when she went to his house. She would practically tiptoe inside, sit quietly in an armchair, and not budge, hoping Edgar would give her some alms.

That was how they had lived for years and years—at the mercy of relatives who weren’t especially merciful.

Despite all the drama and uncertainty at home, Edith threw herself into her schoolwork. She was a star pupil of Marie Suarez, the girl’s division of L’École Cattaui. The newly built private school had opened shortly after she was born and quickly acquired a reputation as the finest Jewish private school. Alexandra had refused to send her to the Sebil—had simply put her foot down. The notion of Edith attending a communal school for the poor was unthinkable to her despite her own penury, and she appealed to her relatives to pay the school’s tuition so that Edith would receive a proper education. My mother was constantly reading and studying and earning accolades. She skipped several grades, received tous les premiers prix—all the top prizes—and was ahead of all her classmates, including those who were considerably older.

From its founding in the 1920s by Moise Cattaui Pasha, then the head of the Jewish community, the school had tried to recruit the finest teachers; and Edith reveled in their love and the attention they lavished on her. The teachers in turn raved about her to Alexandra. What a beautiful penmanship her daughter had—each letter, every word, so perfectly formed. And her compositions were so thoughtful and lyrical.

This was at least in part my grandmother’s doing. Unable to offer Edith any material possessions, too distraught to give her the modicum amount of stability she needed growing up, Alexandra could only infuse her daughter with her own literary sensibility—her passion for books—along with a boundless, all-consuming, near-hysterical love.

There were times Edith chafed at that love and tried to keep my grandmother at a distance. One year that my mother was set to collect all the awards, Alexandra was invited to attend the ceremony. My grandmother decided to wear the lone “dressy dress” she owned, a deep purple velvet outfit she called in her typically fanciful manner, “ma robe de velours héliotrope”—my heliotropetinted velvet dress. It was from another era and hopelessly inappropriate for this hot June day. As they started walking toward school, my mom realized that they made a ridiculous pair and told Alexandra to go home—that she was embarrassed to be seen with her. My grandmother, looking like a wounded bird, walked back to the alleyway alone in her heliotrope dress while Edith went on to collect her prizes.

Usually, they got along and were devoted to each other and exceptionally close. From a young age, Edith was reading the same novels as her bibliophile mother—adult novels, novels intended for someone older and more mature. My mother had the most sheltered upbringing imaginable, yet in some ways it was also the most progressive because of the books she read. She learned about love affairs while reading Flaubert’s Sentimental Education. Her exposure to marriage and its disappointments and betrayals came from Madame Bovary.

When she turned fifteen, Alexandra handed her perhaps the greatest gift of all—Proust’s A la Recherche du Temps Perdu. She had managed to obtain a complete set from an obliging cousin. Within a few months, my mother had read every single volume.

This became Edith’s claim to fame—that she had devoured all of Proust by the age of fifteen. She would say this with a touch of arrogance, because, truth be told, she looked down on other girls her age who didn’t read Proust, who had no interest in him.

There was no such superior streak in Alexandra, who’d been pummeled far too much by life. She was simply thrilled after the years of humiliations to be able to hold her head high again. These days, when she went to see her relatives, it was to brag a little bit, to give them all the wonderful news. She was overjoyed when her daughter received her teaching credentials. “Edith a reçu son brevet” (Edith got her diploma) she told anybody who’d listen. A bit later, she announced, “Edith enseigne” (Edith landed a teaching job). Yet even now that my mother brought home a steady paycheck, my grandmother still went quietly alone every month to collect her one Egyptian pound from balky family members.

As she grew older, Alexandra became more and more fearful. Along with her angst, or perhaps because of it, she was increasingly superstitious. Life was all about good luck and bad luck, how to encourage one and ward off the other, and above all how to avoid what was known in Arabic and Hebrew as ein arah—the evil eye. These beliefs were widespread in old Cairo, and Jews who were educated and cultured were every bit as terrified of the evil eye as their impoverished Arab neighbors. But the fear was carried to an extreme in the ground-floor apartment of the Alley of the Pretty One.

My grandmother was said to be ill fated from the day she was born. From the start, family members spoke of a Curse of Alexandra, which they traced back to her parents, specifically to the day her father, Selim Dana, had married Rachel Dana, a much younger woman who happened to also be his niece. Such near-incestuous unions were tolerated in Egypt—barely—but there were many who were shocked, who shook their heads and said the match was sinister and unlawful in the eyes of God.

“It will bring them bad luck,” people whispered. Ca va porter malheur.

It did. How else to account for the death of Rachel at the age of thirty, leaving behind not only Alexandra but three young sons?

The offspring would be the ones to suffer, those who opposed the union predicted, recalling the biblical injunction about the sins of the father: “For I am the Lord your God, a jealous God, Who visits the sins of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generations.”

Whenever Alexandra experienced another tragedy, another setback, people merely shrugged as if to say, “I told you so.” My well-read, intellectual grandmother also believed in the curse; she was convinced that she was star crossed.

Alexandra was certain her daughter was especially vulnerable to the evil eye because of her beauty and now her teaching job. My grandmother had a thousand injunctions for Edith to chase away the demons and keep those who wished her ill at bay. She believed that running into a priest was unlucky and if my mother ever saw a clergyman coming, she was instructed to cross the street immediately. Now, Sakakini had a Christian girls’ school operated by the Sisters of Sion, so there were many nuns in the neighborhood. The injunction did not pertain to them: Alexandra, educated at a convent school, had a soft spot for nuns and referred to them lovingly as les sisters.

Every week, my grandmother persuaded Edith to join her in a ritual designed to combat those who might wish them ill. Together, they would burn incense purchased in Old Cairo at the souk el attarine—the souk of the spice merchants. In stalls fragrant with the scent of exotic herbs and spices, you could find the men who specialized in selling bakhour—the strange and powerful incense they prepared themselves by mixing aloeswood and musk and sandalwood and clove and cinnamon and lavender and myrrh and mastic and a thousand other secret ingredients.

Alexandra would place the incense in a metal container on the floor and throw a match over it. Almost immediately, the small apartment would be heady with the sweet-smelling fumes. She and Edith would walk around the burning incense seven times—once for every day of the week—to chase away any bad luck and to help usher in good luck.

This was a popular practice throughout old Cairo. There were even “professional” women who came to your home and burned incense and drove away the evil eye for a living. Mostly elderly, they’d arrive bearing their small brass incensory and walk from room to room, shaking it this way and that. The scent of the bakhour lingered for days.

But what was different about the house in the alleyway was my grandmother’s insistence on burning the incense herself, and the degree of passion she brought to the task, and the fact that she instilled in my mother at a young age such a terror of the evil eye, along with the absolute belief in the power of those fragrant, smoldering bits of powder to shield her from harm.

My mother blossomed as a schoolteacher; at last, she was enjoying the status and reputation she and Alexandra had craved. When she walked into class now, all the little children immediately rose to greet her.

Though shy by nature, she emerged as a formidable figure in the classroom. She had a reputation for enforcing strict standards even among her youngest charges. But she also gave of herself more than the typical teacher: If a pupil didn’t grasp a subject, she worked with them in school and after school.

She even made “house calls”—visiting them at their home to tutor them.

But she also brought an abundance of charm to her lessons. She could keep her young male charges spellbound with her fantastical stories, and, of course, she was so pretty that even the littlest of little boys were in love with Mademoiselle Matalon.

And so were some girls. Young Sarah Naggar, who lived on Ibn Khaldoum Street, around the corner from the Alley of the Pretty One, loved to stand on her balcony every morning watching the flow of traffic. She was always monitoring the comings and goings, but her favorite treat was that moment when the lovely Mademoiselle Matalon would pass. She was fascinated by how the teacher carried herself, how her outfits were so dainty and refined—not at all the way other women in Sakakini dressed—and the child could only dream of the day she, too, would put on heels along with frilly white blouses and tailored skirts.

After a couple of years, Edith was handed a plum—the chance to teach at L’École Cattaui.

She was back on familiar territory. The tony private school attracted a different class of students—not rich exactly but fairly well-to-do. Their parents had to pay a monthly tuition. The little boys who attended Cattaui arrived every morning looking sparkling and polished in their satiny black uniforms with the large white Peter Pan collar.

Mom always had a weakness for a nice uniform.

There was an intensity to the education at Cattaui that appealed to her. Young children were required to study four or five languages—French, English, Hebrew, Arabic, and even Italian. They were constantly being tested and given impromptu pop quizzes and oral exams and dictees, the French equivalent of spelling tests. Forced to think on their feet, children learned how to tackle math problems without relying on pen and paper but by making the calculations in their heads.

In an effort to emulate the finest Parisian educations—Paris was always the ideal—a battery of teachers were hired who specialized in every subject under the sun: the basics, of course, such as French grammar and language, which my mother taught, as well as English, mathematics, history, biology and the Bible. There were even courses in calligraphy.

Rome’s cultural attaché in Cairo, a devotee of Mussolini, sent over an Italian teacher, Signorina Messa-Daglia, to help out. She was a blond bombshell, tall, beautiful, and very Aryan looking, who promptly taught her classes the Fascist salute. A Fascist teacher in a Jewish school? Yes: After reciting the Jewish morning prayer in a communal hall, the Signorina’s students greeted her by shouting “Viva Il Duce”—Long live Il Duce—with their arms outstretched.

But that was the only element of fascism that touched Cairo’s Jewish children. Unlike their peers in so much of Europe in the late 1930s, they weren’t subjected to horrific bouts of anti-Semitism or forced to obey demeaning racial laws.

On the contrary, from the royal palace where Madame Cattaui was establishing herself in the court of King Farouk, to the humblest alley in the Old Ghetto, Jews at every level of Egyptian society were enjoying unprecedented freedoms and opportunities. Their lives in this Muslim city were filled with possibilities in ways that had ceased to be the case in most of Europe.

Thrilled with her new position, Edith would get up early each morning, dress carefully with only a hint of makeup to make herself appear older than her seventeen years, and make her way over to Cattaui, a short walk from the alleyway.

The headmaster, a formidable figure named Monsieur Moline who ran both Cattaui and Le Sebil, took her under his wing. As part of his grand plans to raise academic standards and make Cattaui competitive with the Catholic schools of Cairo, which were said to be more rigorous, he was recruiting the best teachers he could find and was said to have a knack at spotting talent. He was a fan of the lovely and genteel Mademoiselle Matalon, gave her choice teaching assignments, and treated her with extraordinary deference.

He also introduced her to the school’s most important benefactress, Madame Alice Cattaui Pasha. Once she became known to the pasha’s wife, my mother—an outsider for so long—was finally on the inside; she had found a second home at 17 Rue Sakakini.

Madame Cattaui Pasha was nearly seventy when my mother came to know her—graceful and proper and dignified yet with a touch of vanity, a hint of la coquette that prompted her to always wear a large choker or kerchief around her neck to hide any telltale signs of age.

She was very much the grande dame in her couturier clothes and white gloves and Paris hats. Yet she was neither cold nor supercilious. Indeed, her greatness lay in the fact that she could consort as easily with a king as with a child in need of a pair of sandals.

She also had a well of goodness within her.

A keen judge of character, she embraced Edith, who found herself the unlikely protégé of this powerful and stately woman. The pasha’s wife became her patron saint and guardian angel and surrogate mother all at once. As a frequent visitor to the school, she could follow my mom’s teaching career and recommend her for new responsibilities. And because this noblewoman had taken such a strong liking to her, the young teacher found herself elevated in everyone’s eyes.

Edith’s newfound stature was almost enough to make up for all the hardships and deprivations of living with my fragile grandmother. Her relationship with Alice Cattaui Pasha made Edith intensely proud, and that pride lingered through the years and decades, sustaining her even when all semblance of pride was gone.

Whenever Madame Cattaui came to the school, the two would huddle, conferring intently on the questions of the day. Edith clung to her as if she were her mother—a mother with the strength and stability that poor Alexandra could never muster. And Madame Cattaui returned the young woman’s affection, treating her like a surrogate daughter—like the daughter she had lost. Because surely that is what happened: My mother was Indji, returned to life again in the form of a delicate and exquisite schoolteacher.

The friendship came with privileges. My mother learned all about the pasha, Yussef Cattaui, and his extraordinary and boundless love of literature, the thousands upon thousands of volumes he kept in the private library at Villa Cattaui—every single possible work of note.

Would she like to borrow some?

It was a startling offer—deeply affecting to my mother who’d had to scrimp and save to afford a steady supply of books for herself and Alexandra over the years; books were so expensive in Cairo. They’d always relied on friends or cousins to give them access to the works they craved or bought them secondhand.

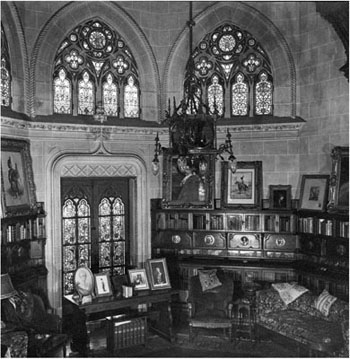

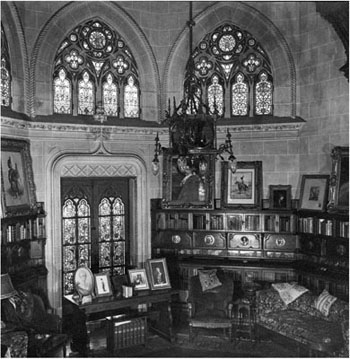

One day, after school, Edith made the journey by tramway from Sakakini to Garden City. It was like traveling to a foreign country—instead of bustling alleyways, there were quiet, landscaped streets, with homes larger than any she had ever seen, with the exception of Sakakini Palace. Finally, she reached 8 Ibrahim Pasha and was ushered into the wing that housed the sumptuous Bibliotheque Cattaui.

With its vaulted ceilings and stained-glass windows, the pasha’s library looked like a church—a cathedral of books. On shelves that lined the walls, many shielded by glass, there were all the authors she knew and loved as well as some she had only heard about and longed to read. She glimpsed a set of Flaubert’s Oeuvres Complètes, from Madame Bovary to the Temptation of St. Anthony. Every novel and poetry collection by Victor Hugo was there, including Notre Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame) and Les Miserables, both childhood favorites. There was Emily Brontë’s Les Hauts de Hurle-Vent (Wuthering Heights) and Tolstoy’s La Guerre et La Paix (War and Peace) and assorted works of Pascal and Emil Zola and Guy de Maupassant and the Goncourt Brothers, all in first editions. Each had an elegant label pasted inside, with the Cattaui family monogram. And, of course, there was Proust—multiple editions of his works containing every volume he had ever published—in jackets of burnished leather.

The pasha’s collection was maintained by a librarian who lived in the Cattaui residence. He was courtly and polite and eager to give Edith access to any works she requested. She settled on Les Thibaud, a French War and Peace that was all the rage. The sprawling family epic by Roger Martin du Gare had recently snared the Nobel Prize for Literature. She lugged all eight volumes of Les Thibaud, from Garden City to the alleyway.

The pasha’s library.

Once Alice realized my mother’s passion for books, the bond between the two women only deepened. Madame Cattaui became sensitive to a widespread problem within the Jewish community—the difficulty for impoverished students to purchase the books required for their studies. Although she and her husband gave to countless philanthropic funds and communal institutions, she had never focused on the struggle families faced to get hold of needed books until Edith told her about her own travails.

L’École Cattaui would change all that. Madame Cattaui decreed the school would have a state-of-the-art library and la chère Mademoiselle Matalon would be the one to organize it. That was the extraordinary project entrusted to Edith—to set up a library that would allow even students of modest means, or simply those with great intellectual curiosity, to read and study and take home any books they fancied.

The two women worked closely together, and my mother was given a budget to order any and all works she felt were important—novels, history and geography texts, biographies, whatever could be of interest to young students. She could purchase them from booksellers as far away as Europe and America; they all knew the Cattauis—the pasha had done business with each and every one of them.

It was a thrilling assignment, and Edith, still in her teens, rose to the challenge. Driven, committed, and thoroughly impassioned by her undertaking, she had never felt so empowered as when she ordered more books, and money was no object, and she could indulge in all her tastes.

She performed her duties with such flair that her reward for creating the library came in the form of a new position. Madame Cattaui installed her as the school’s librarian. She now had two titles and two jobs, since giving up teaching her beloved little boys was out of the question.

Whether she was in the classroom or ensconced in her fledgling bibliothèque or basking in the companionship of the pasha’s wife, Edith had never looked as radiant or appeared so self-confident. She had reached her arrogant years, that period in a young woman’s life when she feels—and is—on top of the world. Although it was a small world, bounded by Sakakini Palace and the careworn Alley of the Pretty One and the Cattaui school, to Mom, it suddenly seemed infinitely grand.

And perhaps only Alexandra, only my poor superstitious grandmother, trembled at her daughter’s sudden surfeit of joy and good fortune and wondered what evil wind might sweep in to take it all away. She begged her daughter—as Mom would one day entreat me—to be mindful of the mauvais oeil, those malevolent forces that lurked everywhere around a person who seemed to have too much.

But the rewards kept coming, and my mother’s luck defied Alexandra’s dark misgivings. Mom continued teaching, ministering to the mischievous boys of la maternelle, who were in kindergarten and first grade, and then, her duties in the classroom over, she would turn her attention to the library.

One day out of the blue, Madame Cattaui arrived with a gift. She handed Mom a key—the key to the pasha’s library.

My mother would always evoke that moment when Alice Cattaui Pasha placed the key in her hands. As a little girl, I would watch mesmerized as she acted out this scene as if from a long-ago play, recalling what happened in a dreamlike voice and obsessive precision:

“La clef, Madame Cattaui Pasha m’a donné la clef, elle l’a mis dans ma main”—the key, Madame Cattaui Pasha gave me the key, she put it in my hand, she would tell me over and over again.

Edith on her wedding day, Cairo, 1943.

For Mom, the key was a precious and ultimately transformative gift that offered a different way of looking at herself forevermore. She was no longer simply a girl from an alleyway, but the fine and talented Mademoiselle Matalon, beloved by a pasha’s wife, embraced by one of the most powerful women of Cairo.