Edith finally—finally—got her wish: I was offered a scholarship to start high school in a tony private girl’s academy.

The chance to escape the public school system couldn’t have come fast enough for Mom or me. The last couple of years at Seth Low Junior High had been a nightmare of unwieldy classes and insipid courses, punctuated by two teachers’ strikes including one in the fall of 1968 that went on for months.

That was the last straw.

Mom found it incomprehensible that teachers would walk out on their jobs. What about the children, she kept asking. It was yet another example of the fatuousness of a system she had despised from the time I’d entered it.

I had my own grievances—the ethnic divides I’d first spotted at PS 205 were even more in evidence at Seth Low, where Jewish kids dominated the “SP” or honor class, while Italians seemed to be relegated to less intensive programs. I was transferred into the honors group shortly after I arrived, and immediately regretted it. I had long ago found a way to coexist with the Italian children who admired my academic zeal and seemed to cheer me on in my unrelenting drive to excel. Not so with the “gifted,” overwhelmingly Ashkenazi kids in the “SP” class. They were clannish, animated by a sense of their own superiority over the rest of Seth Low, and didn’t see me at all as one of their own. I was, to them, an outsider, an intruder. How dare I challenge their intellectual dominance?

Which, of course, I relished doing.

The girls with the golden chais, with names like Gross and Grossman and Friedlander, were out in full force, chatting excitedly about their upcoming bat mitzvahs—the coming-of-age ceremony for girls that was such a distinctly American phenomenon, completely unknown to me and my friends at the Shield of Young David. The girls of Aleppo and Cairo simply didn’t have bat mitzvahs.

My new classmates seemed more affluent. They dressed a cut above the rest of the Seth Low girls, in a kind of uniform that included expensive beige woolen coats. They’d come back from winter holidays with tans, talking about family vacations in Miami Beach. I had absolutely nothing in common with them, with the exception of one gentle, brainy girl named Carin Roth, who seemed to be respected by her peers, and yet devoid of their arrogance. I bonded with her but kept my distance from most of the others and wandered through Seth Low as if in a bad dream.

Then the chance to begin high school at the Berkeley Institute came along with financial aid, and Mom and I seized it. Berkeley wasn’t the lycée, and it wasn’t in Manhattan. It didn’t even have a uniform. But it was an old-line private school, quite aristocratic in its own way—catering to venerable Brooklyn families as well as the gilded nouveaux riches.

Instead of seamstresses and firefighters and sanitation workers, I found myself starting high school side by side with the children of doctors and lawyers and even the Brooklyn district attorney, Eugene Gold, whose brainy, no-nonsense daughter Wendy became my friend.

Mom was overjoyed; “Monsieur Le District Attorney,” she dubbed him.

She was so thrilled when the DA’s black chauffeur-driven Cadillac pulled up to our door on Sixty-Fifth Street. The DA would be in the back with his wife—the car was so roomy it fit several of us comfortably. My friend was as nonchalant about her means of transportation as she was about her status as the district attorney’s daughter. She came to school by limo every morning with her bodyguard-driver and it would have astonished her to learn that my ride in the gleaming Cadillac—even more than the scholarship to Berkeley—was the talk of my family, one of the high points of our five years in America.

The neighbors noticed, of course, as did our new landlords. In a year of changes, we had been forced to leave our beloved apartment on Sixty-Sixth Street after a dispute with the new Italian landlords. We now lived on the bottom floor of a two-family house situated on Sixty-Fifth Street, only a block from our old digs yet it felt a thousand miles away. Our apartment was much larger, but there were so few of us left we felt lost in it.

The Shield of Young David had also closed—suddenly and much to our chagrin. For months, there’d been rumors that it might shut down, but it was impossible to get a straight story as to why—what had gone wrong?

Perhaps those of us who’d remained loyal didn’t want to face the simple truth—that we were yesterday’s news. Our community was moving away, one family after another, and reconstituting itself by Ocean Parkway.

I was about to turn thirteen in the fall of 1969, tall and confident in the chunky brown heels and green tweed minidress I’d purchased both to enter high school and to wear on the High Holidays.

In one last-ditch effort to keep our congregation together, we gathered at a nearby Veteran’s Hall for the Jewish New Year. An effort had been made to replicate our old shul down to the women’s section, but I felt disoriented when I walked in.

Then I realized that everyone else was also trying to make sense of the new environs.

We couldn’t quite figure out what happened, why this Veteran’s Hall was all Rabbi Ruben could muster. It was packed for the New Year prayers—all the old faithfuls were there, which made me wonder why we had shut down in the first place. Surely, it wasn’t for lack of attendance—Ocean Parkway or not, we still had enough Bensonhurst stragglers to fill a synagogue.

To add to the surreal quality of the day, I found myself drawn into one final melee with my childhood nemesis, Mrs. Menachem.

It was a balmy September morning, and my friends and I were chatting amiably outside on Twentieth Avenue. We returned to the makeshift sanctuary only when the Torah scrolls were brought around, a high point of the service. As the men solemnly carried the scrolls past the women’s section, I reached out to kiss one, putting my hand through the new divider, which was a lot flimsier and more porous than the one we’d had at the Shield of Young David.

Suddenly, I heard a scream.

“What are you doing?” Mrs. Menachem was yelling in a voice the entire women’s section could hear above the hymns and chants. I turned around to face her, thoroughly confused, not realizing at first that her words were aimed squarely at me. “What are you doing?” she repeated. She was now standing very close to me and her face was red, and I felt as if she were about to hit me.

Didn’t I know that I wasn’t allowed to touch the holy scrolls? she asked. That I’d reached an age when I couldn’t go near them?

I was too shocked to reply; all the women were staring at us, as were many of the men. I ran out and went home. What had seemed so exciting in the morning—wearing high heels and a short dress and feeling grown-up—Mrs. Menachem had used as a battering ram to put me in my place. Once a young girl reached adolescence, she was considered “impure” according to Orthodox Jewish dogma, and by that definition, she wasn’t allowed near any holy object. That was the point of the divider. That had always been the point, but while I could ignore it all these years, it was inescapable now.

I was almost a teenager, and that meant I was impure.

But I’d never thought my Levantine congregation took the law literally. The women behind the divider were always rushing to kiss the Torah, to physically grasp its maroon velvet covering as it came around. Sure enough, I heard that in the afternoon several of them had confronted Mrs. Menachem and told her she was in the wrong. How could she be so cruel—and on such a holy day—they’d said, springing to my defense.

I was moved by their efforts, but the damage was done. Mrs. Menachem had completely humiliated me—exactly as she had so many years earlier when she’d called me “a silly, silly little girl who was trying to change the world.”

I was starting a new life at Berkeley; why bother with this little VA hall pretending to be a synagogue, anyway?

In all the years Mom had plotted and schemed to have me attend a private school, she hadn’t anticipated the daunting logistics—the fees that even scholarship students were required to pay, the wardrobe needed to keep up with my well-heeled classmates, and especially the long, arduous commute. Both PS 205 and Seth Low Junior High had been within walking distance, so while my mother worried about me constantly—worried about the quality of education I was receiving, the “ruffians” I was befriending—at least I was close by.

Berkeley, located near Prospect Park, was practically at the other end of Brooklyn. I needed to take two trains to get there every morning, followed by a brisk walk through Park Slope, a neighborhood that like so much of New York in 1969 was a strange mixture of the elegant and the seedy, with magnificent old brownstones next to boarded-up homes and dubious characters lurking on street corners up and down Seventh Avenue.

It was thoroughly nerve-racking, this commute.

Edith at first insisted on taking me to school each morning, which she hadn’t done in years. She wouldn’t let go of my hand until we arrived at the door of 181 Lincoln Place, the small faded brick building that housed Berkeley. I balked, anxious about what my classmates would say, and begged her to let me proceed on my own to the school door. “Mais j’ai treize ans—je suis grande maintenant,” I told her indignantly. There she was clutching my hand and treating me as if I were still a child, when I was old enough to take care of myself.

I could tell she wasn’t convinced; what I couldn’t predict was her dramatic course of action.

Shortly after I started Berkeley, Mom announced to us that she had found herself a job: She was going to be working at Grand Army Plaza, the flagship branch of the Brooklyn Public Library.

We were all stunned—each and every one of us, including Dad, who wasn’t even consulted. We had no idea she had even applied for a position, let alone said yes. One day after dropping me off at Berkeley, she had trudged across the expanse of Prospect Park West and interviewed for a job at the imposing library with the big bronze entranceway. And though she didn’t have any of the classic credentials—a college degree or even a high school equivalency diploma—she was able to draw on her vast store of knowledge and her literary sensibility to persuade the library to hire her practically on the spot.

My father was upset, but powerless to stop her; he couldn’t even voice any serious objections. These days, Leon seemed so much weaker and less consequential to the running of our household. He was completely dependent on César, who gave him small sums from his earnings that Dad would then dole out to Mom. We were still struggling financially and Edith had to beg for every dollar to manage, so how could he possibly object to the idea of more cash for the family?

And then there was me. Loulou, cette petite diable, Mom would say fondly; “Loulou, that little devil.” Now that I was attending a fancy school, I kept pressuring her for expensive clothes as well as more pocket money so I could keep up with my chic classmates.

It made eminent sense, her going back to work. Yet my father couldn’t make his peace with it. Edith was changing before his eyes, and it was as if America had delivered one injury after another.

A year or so earlier Mom had gone to be fitted for new dentures; the first set, obtained with the help of a social worker shortly after our arrival in New York, had been so painful and ill-fitting that she simply never wore them. But the new ones, made at a free clinic in Brooklyn, were more comfortable and she forced herself to get used to them. She looked so much more attractive: She could flash her lovely Ava Gardner smile again.

With a few tweaks to her wardrobe, thirty years after her post at L’École Cattaui, my mother was ready to return to work at a library.

It was a part-time job and she was only a clerk. Her pay was a pittance—barely above minimum wage. But no matter, to her mind she was going back to those halcyon days working with the pasha’s wife. She would be her own woman again, and more important still, she would be surrounded by books.

She was so devout, she viewed this in near-mystical terms—as if God were giving her another chance. And, of course, since Grand Army Plaza was close to Berkeley, she would be able to accompany me every morning. I hadn’t banked on her indomitable will.

We reached a compromise. We’d set out together in the morning, first by subway to DeKalb Avenue, then changing trains to Seventh Avenue and the long dark station that led out to Park Slope, an area that veered between faded elegance and decrepitude. Mom would walk me to the corner of Lincoln Place and, reassured that I was only a block or so from school, she’d finally let go of my hand and begin the uphill march by herself to the library.

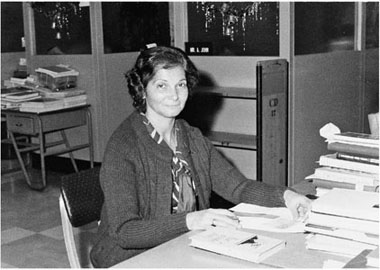

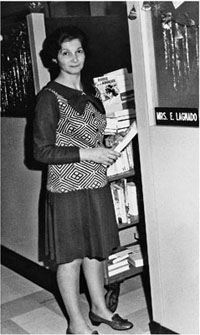

Edith surrounded by books at her desk at the Brooklyn Public Library, Grand Army Plaza, circa 1970.

It was an enormous trek, and I would find myself worrying about her as she sprinted toward Grand Army Plaza. She had a choice of routes, but none was especially pleasant; and they all required her to cross the biggest, most dangerous traffic circle in New York. Grand Army Plaza was a maze of converging streets and dizzying thoroughfares—Flatbush Avenue, Prospect Park West, Eastern Parkway, Vanderbilt Avenue, Plaza Street, Union Street—and crossing it meant taking your life into your hands.

The walk was arduous even in the best of circumstances. Occasionally, she’d cut through a small park that led directly to the archway at Grand Army Plaza, but it, too, had its drawbacks. One day, she was accosted and knocked to the ground by one of the young thugs who lay claim to this deserted patch of grass. She learned to simply run, run through it to get to work.

Once she made it to the stately old building shaped like an open book, she could breathe again. She loved the grand entrance with its shiny bronze statuettes of literary icons—Tom Sawyer, Rip Van Winkle, Hester Prynne, even Moby Dick and the Raven.

From the start, she found the library embracing and safe, a world unto itself, a family even as ours was crumbling. Suzette had taken several trips to Miami and was hoping to settle there, despite Mom’s entreaties that she stay close to home. Isaac had left us a couple of years earlier, first to attend a state university in Memphis, then transferring to Bowdoin, at that time a Waspy, preppy men’s college nearly four hundred miles away in Maine. Every once in a while César spoke of moving out as well. He was barely around, always off with some girlfriend or attending night school or working late.

That left Dad and Mom and me in our vast new apartment, hanging on to each other for dear life.

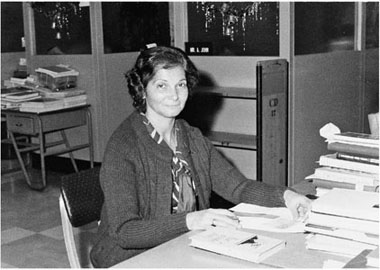

Ed Kozdrajski, Edith’s colleague at the Brooklyn Public Library’s catalog department; she referred to him as “le gentil petit Ed,” sweet little Ed.

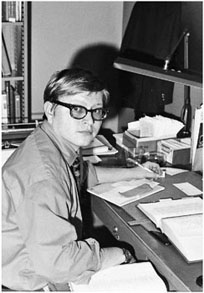

The library offered Edith a home that seemed far more hopeful. She was brimming over with stories about her colorful colleagues. She couldn’t wait to tell me about the mysterious Ukrainian exile and former lawyer, Alex Sokolyszyn, whom she always addressed by the honorific “Docteur Alexis”; he was her favorite. He had a Ph.D.—it was unclear in what field—and he, too, had suffered a fall in the move to America and was forced to reinvent himself and start again. Offered a job as a cataloger at Grand Army Plaza, he acquired a reputation as the ultimate authority on foreign-language books. Erudite, courtly, and thoroughly old-world, Mom idolized Docteur Alexis.

She found another kindred soul in Fawzia El-Araby, a cataloger from Cairo. The two were constantly chatting and joking, switching back and forth between Arabic and English. When Fawzia brought a Middle Eastern lunch—falafel in pita, which Edith favored above all other foods—she’d share it with Mom. Fawzia was a Muslim, and their friendship reminded Mom of the old days in Egypt, when her social circle had included Muslims and Christians and Jews, and those differences simply didn’t matter. There was also tender Jean Nason who was handicapped and struggled to do her work despite a severe case of scoliosis, and she had trouble speaking. Mom found her so moving; Jean, she’d tell me, managed to be a superb cataloger despite her physical impairments. She also developed a bond with Ed Kozdrajski, a handsome young catalog trainee with a serious manner about him. He wore thick black-rimmed glasses that made him look stern, when he was actually very gentle and especially solicitous of her. Ed was of Polish descent but born here in New York, and he and the other Americans were in the minority. Her closest companion was Mudit Strasdins, a honey-blond refugee from Latvia by way of Canada whom Mom called Madame Mudit.

Alex Sokolyszyn—Docteur Alexis, as Edith liked to call him—was a Ukrainian exile who reinvented himself as a cataloger of foreign-language books at the Brooklyn Public Library.

She felt at home among these exiles—expatriates and émigrés and loners every bit as lost and diminished as she was in America. They banded together in a crowded corner of the third floor of Grand Army Plaza and there, amid carts bulging with books in every language on earth and rickety steel shelves crammed with the thick reference volumes of the Library of Congress and the stacks of beige catalog cards that Mom and other clerks typed up throughout the day, they rebuilt the hearth.

There were constant parties and café klatsches and get-togethers. Any occasion—a birthday, a wedding, an anniversary, a holiday—called for a cake and cookies and steaming cups of coffee or my mother’s favorite, chocolat chaud, which she believed offered her all the nutrients she needed to survive.

Docteur Alexis, Madame Mudit, pauvre Jean, La Fawziah, le gentil petit Ed Kozdrajski, “sweet little Ed Kozdrajski,” who she always called by his first and last name: Her colleagues were her favorite topic of conversation. Through her telling they emerged as larger than life, major characters in the novels Mom was always beginning in her mind and could never quite put on paper save for some random jottings here and there.

Then there was the paycheck. For the first time in years, she wasn’t dependent on my father or César to live. Mom now had a little money to spare, a little money to spoil me, more money than she’d had since the years with the pasha’s wife because for all her married life, even the period of relative ease and comfort in Egypt, she had been at Dad’s mercy, relying on his beneficence—or lack of it—to make ends meet.

The library had changed all of that—it had restored her sense of self, it had made her independent. Edith’s transformation from Levantine housewife into career woman extraordinaire was in keeping with the changes sweeping America, and at breakneck speed. The feminist movement had gone from an imploring whimper to a raucous and angry call to arms and Mom, the delicate porcelain doll who for years couldn’t stand up to my father, who consistently sacrificed herself to his needs and ours, now had that most wondrous of possessions—a disposable income.

As the 1960s came to a close, my mother emerged as a small, unlikely, thoroughly unheralded emblem of women’s liberation.

My life had also changed. Berkeley was a cloister—a secluded and largely female universe where the outside world didn’t seem all that relevant. My entire freshman class consisted of twenty girls

In the years before I arrived, my classmates—who had been attending Berkeley since they were small children—learned how to curtsy and the proper etiquette for serving tea. The school emphasized quiet and decorum—in its hallways and careworn library and wide staircase with its gleaming old wooden banisters.

Even gym was different—gentler, more graceful than I’d known it.

I wore a stylish dark green tunic over a white shirt and studied fencing, archery, and badminton—sports where I actually showed promise. Fencing, in particular, reminded me of Emma Peel. I never thought about her much these days; my obsession with her had faded with the passing of my childhood. But donning the white protective garb, steel foil in hand, took me back to those years when I’d loved to watch her thrust and parry and prayed I would grow up as fearless and talented as she.

I bonded with my teachers in a way I never could at Seth Low; Berkeley was simply a different world. I had a crush on Mr. Gardine, the elegant southern gentleman who taught us English and came to class dressed in exquisite blazers, silk ties, and two-toned shoes. I found him deeply exotic—his accent, his manner, and his assignments, which were always somewhat out of the ordinary.

But he was often stern with me; his notes to my mother warned that I was “solipsistic” and measured life “by the yardstick ‘I.’ ”

One day, instead of giving our class one book to read and discuss, he selected a different novel for each of us—works he thought we would enjoy because they suited our individual temperaments. “The Death of the Heart, by Elizabeth Bowen,” he said, pointing to me.

It was about a young girl of about my age who is always an outsider, who never feels at home anywhere.

Islay Benson, the aging spinster who ran the theater department, was perhaps my favorite among all the teachers. With her British accent, accent, 1940s hairdo, and severe clothes out of another era, she was a definite eccentric, an oddball in this fashion-conscious Brooklyn girls’ school. Miss Benson favored shirts with big pointed collars and long pencil skirts that brought to mind Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday. She had studied drama with Frances Robinson-Duff, “the acting coach to the stars” who had taught Katharine Hepburn and Clark Gable. A quarter of a century earlier, in 1944, she’d had a starring role in a Broadway thriller, Hand in Glove, directed by the same man who discovered Boris Karloff and cast him as Frankenstein. Her theatrical past could have made her haughty or superior, but I found her, on the contrary, accessible and kind; and I felt more energized by her drama workshop than by my other courses.

Loulou, the year she attended the Berkeley Institute, Brooklyn, 1969.

We practiced Twelve Angry Women, an adaptation of the Reginald Rose play, and I was asked to read a small part, playing one of the minor jurors. I hadn’t acted since my long-ago stint as Haman, but I still had a passion for the spotlight—I loved showing off, reciting out loud, being on a stage.

I was already a seasoned actress in my own way. I was still pretending to be French—a little Parisian girl, not a Cairene. It was a role I’d assumed at Mom’s suggestion in our early years in New York, when she thought it would be hurtful to say I was Egyptian. It was easy since I spoke with a heavy French accent then, and I was said to “look French.”

Even now, in high school, I was still pretending. I didn’t tell my Berkeley classmates very much about my Cairo origins. Nobody needs to know, I thought, recalling my mother’s warnings that Americans simply wouldn’t understand our background, that they’d have no sense what it meant to be from Egypt. Americans had such loopy notions of Egypt, she’d say. She worried that they would dismiss me as coming from a backward and primitive country.

Besides, being French carried so much more cachet at Berkeley.

Freshman class at the Berkeley Institute, 1969/70; Loulou, standing a bit apart from her classmates, is in the front row on the left.

The first jarring note in high school came at assembly one day, when a senior, a daughter of a rabbi, recalled going to Woodstock in the summer. I heard about flower children and the hippie movement for the first time in the auditorium of the Berkeley Institute in the fall of 1969. But that was the exception: Our lives, complete with Latin classes and dress codes, had nothing in common with the furious goings-on outside. Our teachers were clean-cut and conservative in the extreme, and life was staid—not at all about the abandon and recklessness that Woodstock and the sixties had come to emblemize.

Mom noticed a change in my friends—they were so polite, these Berkeley girls. She simply melted when Wendy Gold called and asked her in French, and with such refined manners, whether I was home: “Est-ce-que Lucette est la?” That was exactly the sort of friend she hoped I would have.

When Berkeley announced its first dance of the year—an old-fashioned “mixer” with the boys of Poly Prep Country Day School, an elite Brooklyn private school—there were so many rules and restrictions in place that having fun seemed almost beside the point. First and foremost, a strict dress code was put in place. Dresses and skirts had to be of a certain dignified length, and pants were off-limits. Jeans, of course, were thoroughly out-of-bounds. Some of my more fashion-conscious classmates were dismayed; they argued for permission to at least wear the sleek pantsuits that were all the rage.

Weeks of deliberation and planning ensued. The dance was going to be chaperoned, our parents were assured. There was to be no alcohol, and drugs were quite unknown. The mother of my classmate Kim had volunteered to drive both of us to Berkeley and planned to take me home later that night; with that guarantee, off I went to my first dance.

Yet for all the build-up and worry, it was an awfully tame affair. I walked upstairs to the assembly hall, which had been decorated and transformed into an elegant ballroom. There were the boys of Poly Prep in jackets and ties, eyeing us as we came in. Several of my classmates had dressed up as if they were going to a wedding; one student wore a striking, formal red chiffon dress. I wore a pale pink brocade sheath I had purchased the year before at Stern’s, the grand old Manhattan department store, as it was going out of business. I had worn it only once, to the Newark wedding of one of César’s boyhood friends. When I’d gone out on the dance floor, the band struck up, “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby,” as the conductor smiled and waved at me. I never felt quite as wonderful or grown-up as that night in Newark, and I figured it would bring me good luck to wear it again. It fell chastely past my knee so I easily passed muster with Berkeley’s dress code police.

An earnest, quiet boy about my height came over to introduce himself and ask me to dance. His name was Henry Finkelstein, and I was too taken aback to say yes or no—to say much at all—but I spent the evening only with him, dancing and listening to him chat about “Poly” as he airily called his school. He struck me as sweet and unassuming—in no way a snob. I noticed that he had wonderful green eyes—Maurice’s eyes.

He phoned a few days later: Did I want to go to a dance at Poly?

Henry came from an entirely different background—a different world really—than mine. His father was a surgeon, and his family lived in a brownstone in Park Slope, by Prospect Park. His mom volunteered at the Brooklyn Museum, and his two younger sisters were also enrolled at Berkeley. One, Susan, was only a grade below mine. She seemed to be eyeing me curiously in the days after the dance, and I wondered what on earth her brother could have told her about me.

“Loulou, tu va sortir avec un garçon?” my mother asked me, sounding an awful lot like Dad in his stern Old Syrian mode—Are you planning to go out with a boy? I argued that a dance at Poly Prep wasn’t really a date—though, of course, that is exactly what it was.

Henry was un garçon de bonne famille, a boy from a good family: I figured that Mom would like that. But my efforts to soothe and reassure her failed. I couldn’t appeal to my father, of course, who would have been even more intransigent. Strangely, he didn’t even figure into these discussions. He was so withdrawn that the task of bringing me up as I edged into my teenage years was left entirely to Mom and César.

Now pushing seventy, Dad was tired, defeated from the skirmishes and all-out battles with my older sister. He seemed loath to get involved with raising another teenage daughter, so César stepped into the breach and began acting as my de facto father.

My mother found a kindred soul, someone in whom she could confide her worries about me and my schoolwork, my friends, and now, my emerging romantic life. The two conferred at length and came back with the firm answer: no.

It didn’t matter that Henry’s father was going to be driving us. The answer was still no.

Finally, as the entire evening risked being torpedoed, Henry’s mother personally intervened. She promised that she would accompany us; both she and her husband would take us to the school dance, she assured Mom. Mrs. Finkelstein was so gracious and persuasive that Edith found herself saying yes even as I contemplated the prospect of going out with a boy and meeting his father and his mother all on the same night. I had never gone out with a boy before. The years that I had spent dreaming of Maurice, plotting ways to earn his love, had resulted in … nothing.

Yet here I had gone off to a dance and ended up being asked on a date after one evening.

Growing up certainly had its advantages.

In the days prior to the dance, I walked up and down Eighteenth Avenue, anxiously combing the stores with Edith in tow. Somehow, the bargain shops I’d always found so abundant seemed inadequate for the occasion, and I wandered restlessly from one to the other. I had no idea how to dress for a first date. Provocatively? Demurely? The Saturday of the dance, I finally settled on a pale blue flowered dress that was rather prim. It had long sleeves and a small white collar and it grazed my knee so that I looked the picture of modesty.

That evening, as I put the final touches on my outfit, I could feel my mother and brother inspecting me. Edith looked a bit wistful. I probably hadn’t seemed grown up to her until that night, when I left to go to the dance with Henry Finkelstein, both his parents waiting for us as promised in the car downstairs, even as his dad curiously eyed our simple two-family house.

After I left, Mom sat down and penned a letter to my sister.

Dear Suzette:

One hour ago, they came to pick her up—this little young man, as tall as Loulou, who is now taller than me, his mother, so beautiful, so chic, and his father, too—he’s a doctor in Manhattan with the most stunning car imaginable. Loulou, what a little devil… With each invitation she receives, César and I have to come up with a new wardrobe for her.

Henry Finkelstein and I didn’t dance much that night. Mostly we wandered around the grounds of Poly Prep, a vast campus of ponds and rolling brooks and wooded enclaves in between stately old buildings. It was hard to believe we were in Brooklyn. There was a dreamlike quality to our walk, and I had trouble focusing on what Henry was saying. He was clearly overjoyed to be showing off his school; the campus was more than twenty-five acres, he boasted.

Finally we reached one of his favorite buildings—the gym where he said he was studying wrestling. I must have looked surprised—he was so slight, not much taller or heavier than I was. It was a special kind of wrestling class Poly offered, “For ninety-eight-pound weaklings,” he volunteered. We walked round and round a large room in the basement that had mats spread out all over the floor; on the wall were vintage black-and-white pictures of student wrestlers from years gone by. I peered at the pictures intently, as if seeing them was the point of the evening. I wasn’t really sure what to do.

The dance over, his parents drove me home and that was that.

It had been a perfectly amiable evening, but to my secret relief, I never heard from Henry Finkelstein again. It would have been agonizing to ask Mom if I could see him again, to seek César’s permission.

And that is how my first relationship with a boy ended—before it had even begun.

We weren’t prepared for the perils of a Park Slope winter, which somehow felt colder than cosseted Bensonhurst. Neither Mom nor I knew how to dress properly for our daily expeditions to Lincoln Place and Grand Army Plaza—the glacial subway stations, the walk through wide-open thoroughfares buffeted by wind. I, at least, had a knitted scarf and a hat. But Edith insisted on wearing the same little nylon kerchief she used in synagogue to cover her head, and that she’d purchased for ten or twenty cents from Woolworth’s. She had a collection of these kerchiefs in a drawer at home, and on extremely cold days, she simply wrapped another, identical one around her neck and ventured outside; I wondered how those two flimsy swatches of fabric could offer her any protection.

She had recently bought a long woolen coat that came down to her ankles. It was too big, more bulky than warm really, but it was of that dreamy shade of blue she fancied above all other colors, bleu royale, with gold buttons. After she kissed me goodbye, I would watch her run, a small thin figure in an impossibly large coat racing, racing to get to her job.

There was a perk that came with life in the Catalog Department: All the latest books crossed her desk, the books that drew the critics’ attention and were the talk of literary New York. It was her job to help make sure they were sorted and processed to be divvied up among Brooklyn’s vast network of sixty branches. She’d consult the massive tomes of National Union Catalog, published by the Library of Congress, to figure out the edition of a particular work. She mastered the Dewey decimal system and learned how to search through the four volumes of Dewey Decimal Classification. She was at ease using the many bilingual dictionaries on her desk, her facility in languages coming to her rescue. She’d also type up the little catalog cards that made a book an official part of the library system.

She was amazed at the range of works she was handling—not simply recent bestsellers but, for example, a 1950 edition of The Complete Works of Homer, The Iliad, or The Secret of the Hittites: The Discovery of an Ancient Empire, published in 1956, the year I was born, or Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbinders in Suspense, out since 1967.

She approached even the most menial task with relish. As she cataloged a volume of poems by Pushkin, for instance, she’d find herself reading it and taking notes. She might have been running the entire Brooklyn Public Library, she was so passionate about her work.

One evening Mom came home raving about a young author named Philip Roth who had published a splendid novel. She had been reading Portnoy’s Complaint on her coffee breaks and found it “très risqué,” she said with a chuckle, as she handed me a copy, “mais formidable.” Another time, it was a new novelist, Joyce Carol Oates, who caught her eye. At home, she talked and talked about Joyce Carol Oates and wouldn’t rest until I’d promised to read Expensive People.

Once I started it, I was horrified yet I couldn’t put it down. It was a novel about a child who kills his mother and confesses to the crime, but no one in his affluent, well-heeled little town believes him.

At last, Mom felt connected to the world of literature she had coveted and that had eluded her most of her life. Not since Cairo and her work with the pasha’s wife had she enjoyed the literary companionship she now found every single day at the Catalog Department of the Brooklyn Public Library.

Berkeley was ruled by a charming, elegant, and utterly dictatorial headmistress named Mary Sue Miller. Mrs. Miller was personable but rather terrifying. It was her first year and she had grand hopes for Berkeley, to liberalize it and bring it to a new era. But that didn’t stop her from looking after the teensiest details or enforcing its ancient rules. She cultivated us, got to know us one by one. In that sense she was very different from the principals at my elementary school and junior high—cold, distant figures who sat closeted in their offices, emerging only for assembly or graduation. I had the sense that Mrs. Miller knew my particular strengths and my flaws. I didn’t think she liked me very much.

When Wendy appeared in school in culottes, Mrs. Miller promptly sent her home for violating the dress code. She was constantly on patrol, and I noticed her walking down the hallways and darting in and out of classrooms. She wielded absolute control over every aspect of the school and of our lives.

Or so it seemed at first.

By my second semester, events outside were being felt within our little classroom. I wasn’t sure anyone—even the formidable Mrs. Miller—was really in control. Fashion was changing, music was changing, the culture and even the mood of America was changing; and with the mounting anger over the Vietnam War, there was nothing sedate about what was taking place.

Betsy Raze, one of the brainiest girls in the class—and the most outspoken—arrived one day in a see-through blouse and no bra.

Technically, I suppose, she hadn’t violated the dress code, which didn’t have a clause about bras or gauzy blouses. To our amazement and hers, she got away with it. She wore the blouse again and again, sometimes with a short frosted brunette wig she fancied, and always with high heels, so that she appeared considerably older than her fourteen years.

The feminist movement was reaching a critical point. Traditional ideas about marriage and children were under siege and a new bestseller, The Population Bomb, was causing a stir at Berkeley, where even the head of the lower school raved about it. The book, by Paul Ehrlich, made dire predictions about what would happen if people had too many children and urged drastic action, including sterilization, to restrict the size of families to no more than one or two kids. I remembered how excited I’d been over these ideas years back at the Shield of Young David, and Marlene’s contemptuous reaction.

Marlene was now married to a handsome Israeli named Avi. She and her husband had settled in Brooklyn, not far from the Syrian community of our childhood, with hopes of starting a family. I felt a million miles away from her—part of a new world, a world that was drastically different from the one she and I had once inhabited behind the divider.

When Berkeley decided to hold another dance, the rules that had tied us up in knots months earlier seemed antiquated … irrelevant.

Since our first mixer, pants with flared legs had replaced skirts and dresses for formal occasions. The dance was held in the gym, a large unsightly room that wasn’t at all elegant or gracious like the assembly hall we’d used for the fall mixer. When I walked in wearing my demure little pale blue dress—the one from my date with Henry Finkelstein—I felt awkward and uncomfortable.

The music had also changed—it was much louder, much harsher. Psychedelic rock and heavy metal had replaced the more melodious sounds of earlier in the year, the Fifth Dimension and Jay and the Americans swept aside by Frank Zappa and Jimi Hendrix and Janice Joplin, and I found the new rhythms—the revolution that Woodstock had wrought and that had finally reached us at 181 Lincoln Place—unpleasant and discordant.

A few of my classmates were smoking. I felt disoriented by the music, the atmosphere, the couples that had suddenly formed all around me. I didn’t see Mrs. Miller anywhere and for once, I missed her, missed the order she imposed wherever she went.

I left without mingling with a single boy from Poly Prep or any other private school. I wanted only to be back in my room with my Charles Aznavour records, or listening to Dalida with Mom.

And suddenly, a social movement that I’d supported ardently from afar, that had seemed appealing from the vantage point of the women’s section in my small synagogue, began to seem frightening and disquieting. The more strident and militant women sounded, the more freedoms they embraced, the more I wanted to retreat. But retreat to where? Even this elite private girls’ school was turning out to be as turbulent as every other corner of American society at the dawn of the 1970s.

It was as if the world no longer had any safe harbors or women’s sections or dividers.

Literally so, as I learned the day I went back to visit the Shield of Young David. I wanted to see for myself what had happened since its sudden closure several months earlier—if anyone had taken it over. I managed to enter the deserted building through a side door that had remained unlocked. Downstairs, in my old Hebrew school, the classrooms were still there, untouched, eerily silent. I made my way to the basement and a room that had haunted my childhood. It was usually locked, but once or twice my friends and I had been able to sneak in, always amazed by the sight of what looked like a swimming pool. It was actually an old ritual bath—a mikveh—where married women were supposed to go once a month and immerse themselves in a symbolic act of renewal, a process that made them “pure” again.

The room scared us, my friends and me, and we’d stayed away from it as children, not really understanding its purpose. Now, with the door left ajar, I decided to peek in. The lights were out; the water had been drained; there was refuse at the bottom of the pool. The room looked otherworldly, as if there still lurked the ghosts of bathers who had gone over the years to be purified of the sin of being female.

Finally and with some trepidation, I made my way up the familiar staircase to the sanctuary. It looked completely forlorn. The chairs were gone; the Holy Ark was gone, the bookcases that lined the wall had been emptied of all their books—no more copies of The Kiddush Cup That Cried, or Rabbi Avigdor Miller’s attack on Darwin’s theory of evolution.

And the women’s section—it, too, was gone.

The wooden partitions had all been torn down; stray pieces were scattered in the back. The sanctuary was open and airy, but, alas, no one was there to enjoy it. Once upon a time, I realized, the mere thought of those dreaded barriers coming down would have filled me with glee. But I felt strangely desolate seeing the divider reduced to dozens of pieces of wood, ready for the trash. I wished that I could gather them and hold on to them.

When Miss Benson announced that Berkeley would be staging Ring ’Round the Moon, a play by Jean Anouilh, it seemed natural I should audition: The drama teacher herself urged me to read for her. But I didn’t dare get my hopes up—I expected that all the major roles would go to upper-class girls. To my surprise, when the cast was posted a few days later, there was my name at the top. I had been given the plum role of Isabelle, the lovely young ingenue.

I hadn’t been so excited since my last acting stint as Haman, the Evil One, in my temple’s Purim spiel.

This was the major production of the year—boys from Poly Prep were going to play the male parts.

Miss Benson made it clear she believed in me: I was going to be a star. But rehearsals would take place after school and could last well into the night. Our parents had to give their explicit permission for us to be in the show. When Mom heard about the late sessions—with boys, no less—alarms went off. Once again, she huddled with my brother; the two decided that no, I could not accept the part, it simply wouldn’t be safe.

I couldn’t seem to argue with either my mom or César about their decision. They weren’t budging, and nothing I said had any impact.

I didn’t have the courage to defy them.

My mother was enjoying her newfound authority. With César supporting and guiding her, she displayed a stern side I hadn’t seen very often. I realized that I missed my father’s involvement in my life. Despite his legendary toughness, I had always considered Leon to be fair, and he tended to be mild with me. But he was in retreat now, the Invisible Man. Nothing any of us were doing—me in my high school agonies, Isaac away in college, Suzette off to Miami, Edith working—seemed to matter much to him anymore.

Mom’s refusal to let me star in the play took the school aback. In an extraordinary step, Mrs. Miller sent her a letter urging her to allow me to join the production. She even promised that I and the other girls would be escorted to the subway every evening by the Poly boys. It was to no avail. No one, not even the headmistress, seemed to have any influence on my mother. Another girl—a sophomore—was tapped for the lead.

I was so crushed I refused to see the play.

In the weeks that followed, my mood, my entire outlook, seemed to change—I felt restless and agitated. I wasn’t sure I wanted to be at Berkeley anymore. While I still got along famously with teachers like Miss Benson, I clashed with others. I had testy relationships in French class and gym, where I found the teachers to be martinets. I bristled when I dealt with anyone who struck me as bossy—which, of course, didn’t serve me in good stead with that ultimate boss, the headmistress.

I now skipped gym class whenever I could. We had moved on from fencing and archery and badminton to field hockey and exercises on uneven parallel bars and pommel horses that I hated. I’d pretend to be sick and spend the period in the infirmary, being comforted by the school nurse, who allowed me to lie down and go to sleep.

Even my English teacher, Mr. Gardine, noted how much I had changed. He told Mom that I “could do better work.”

Despite my recent ennui, I had thrived at Berkeley. I was much more assertive than I had been in public school. Emboldened by the As I was receiving along with all the encouraging comments from faculty, I was outspoken and overly confident, with emphatic opinions on every subject on earth, including subjects about which I knew nothing. I secretly felt superior to everyone around me.

Mr. Gardine tried to rein me in, telling me again and again I was too opinionated and self-absorbed and intolerant of others.

It was to no avail.

I had always done well in small, sheltered environments, and Berkeley had brought me back to the way I’d been in the women’s section—supremely sure of myself, an Egyptian princess in Brooklyn.

One day, my mom was summoned to the school for a meeting with Mrs. Miller.

“Your daughter is arrogant,” the headmistress told her. Edith was taken aback—she didn’t know what to say, but her instinct was to apologize immediately and profusely on my behalf. When she came home, she seemed terribly upset and called me into the kitchen. As she fixed herself some Turkish coffee, she began quizzing me on what I could possibly have said or done to make such a poor impression on la directrice.

“Loulou, des fois tu exagères”—Loulou, sometimes you really are over the top—she said with tremendous sadness.

In the final weeks of the year, as the weather grew milder, going to school felt as it had at the beginning—serene, otherworldly. Sometimes we would have classes on the grass in Prospect Park. I had once again this sense of being in an idyllic, shielded environment, protected from the rest of the world.

That sense of calm was shattered when news broke of the shootings at Kent State University. National Guardsmen had fired on students who were protesting the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, killing four and wounding several others and sparking nationwide protests. Most schools in New York closed for a day as a gesture of mourning. When Berkeley remained open, the students declared a strike and refused to attend classes.

Mrs. Miller was upset, but what could she do?

Senior girls sought and received permission to wear black armbands at graduation in solidarity with the fallen of Kent State.

As if mirroring the general mood, I felt angry and rebellious, too, and wanting to protest—but to protest what?

I had recently picked up an American expression: thanks for nothing. I would use it mostly on my friends, jokingly, of course, but with a slight edge. “Well, thanks for nothing,” I’d exclaim, feeling very American as I walked away from them.

We had a French exam, and several of us were upset with the teacher. But of all the students, I was the one who felt a need to convey my displeasure. I scribbled “Thanks for nothing” at the bottom of the exam paper. I was very pleased with myself. I put this teacher in her place, I thought.

Edith was asked to come in, of course. The school was crisp and to the point: Berkeley was not renewing my scholarship.

My mother was devastated, but when she gave me the news, I felt curiously detached. It was a terrible setback, of course, but I refused to see it that way. I’d already decided I was ready to move on.

Fine, I’ll attend New Utrecht, I told Mom coolly.

“Tu retournes a une école publique—quelle horreur,” she said; A public school again—how awful. She looked more despairing than I had ever seen her.

It had taken Edith five years to get me into an elite private school only to see me lose it in the space of ten months. What was it about me and my siblings, she cried, that we always squandered opportunities? Was there a curse on our family?

She was almost talking to herself now, bemoaning how God had given her children “toutes les grandes qualités,” all the assets needed to prosper and do well on this earth—intellect, beauty, charm, personality.

For all the good it had done any of us.

Look at Suzette, she said, with the rage that flared up whenever she discussed my older sister, frittering her life away in odd jobs from Queens to Miami, no family, no husband, no children, no home, building nothing, achieving nothing. And now me, losing Berkeley, forced to attend cette sale New Utrecht, this awful New Utrecht.

I listened, impassive, to her outburst. Then I tried with all the calm I could muster to say that her illusions about private schools were only that, illusions. After a year in Berkeley, I wasn’t sure there were that many differences between American children, no matter their social and economic backgrounds.

The changes the late 1960s had wrought had seeped everywhere into the culture. Those idealized young girls of my mother’s imagination—les jeunes filles rangées—the proper, demure girls of the navy blue blazers with gold buttons and pleated skirts who had haunted my childhood didn’t exist. Once upon a time perhaps, in Cairo or Paris, I would have met these delicate, refined creatures, but they weren’t to be found in New York City at the dawn of the 1970s.

I didn’t address my mother’s larger fear—that each of us carried a self-destructive gene deep within us, that we were beset by demons and destined to trip ourselves up, and that calamity always lurked around the corner.

This was a recurrent theme for Mom, especially when she was in one of her dark moods. I had grown up hearing about the Curse of Alexandra, my wondrous and tragic grandmother. In recent years, my mother spoke of my sister as if she, too, were cursed—plagued by bad luck.

It was troubling to find myself included in that pantheon of star-crossed family members. Truth was that I didn’t really know why I was leaving Berkeley, and why—or how—I had self-destructed.

After the school year ended, Wendy Gold and I made plans to get together. On a sun-drenched day, we walked through the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens and explored the lush plants and flowers and talked and talked.

I felt so sad; it was dawning on me I probably wouldn’t see Wendy again.

I arranged to transfer to New Utrecht High in the fall even as my mother carried on with her work at Grand Army Plaza. She was facing a major change of her own, one that she dreaded: The library announced that the Catalog Department was going to be moved to its own building many blocks away. The department would be lodged in a windowless, converted garage on Montgomery Street, a bleak area of warehouses and abandoned factories.

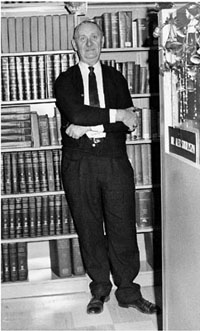

In 1970, the Brooklyn Public Library gave Edith her own cubbyhole with her nameplate. She had reinvented herself as a professional woman a quarter century after leaving her teaching post in Cairo.

But once ensconced on Montgomery Street, Mom and her colleagues discovered some redeeming features to the move. There was more space; they weren’t all cramped together the way they’d been at Grand Army Plaza. And come lunch, they could wander over to the Botanic Gardens, which were literally around the corner, and dine outdoors while enjoying the wonderful greenery. Occasionally, Mom would buy a small plant for a dollar or two and bring it home because even a potted lily on the windowsill ça nous aidera a reconstruire le foyer—would help in rebuilding the hearth.

One day, my mother learned that she was being given her own office. It was very small, a cubbyhole really, but it came with a nameplate that said “Mrs. E. Lagnado.” It may as well have been a corner office with a view—she was so thrilled with her new status.

Ed Kozdrajski, the young cataloger Mom found so charming and unassuming, came to work with a sleek camera he had purchased; photography was his latest hobby and he asked Edith if he could take some shots of her. She was delighted to oblige. In one photograph, she sits regally at her desk, her head held high, her back ramrod straight. In another, she stands beaming in front of her nameplate.

Ed’s images captured what my mother herself couldn’t put into words—that once again her world seemed filled with possibilities. She felt as if she had been given a new life; she experienced that same sense of buoyancy and soaring optimism as that day when Madame Cattaui Pasha had handed her the key to the pasha’s library.