My parents loved to travel. My mom, a native Montrealer, had attended graduate school in Belgium and spent a year exploring pockets of Europe and the Middle East before moving back to Canada and settling in Toronto, where soon after, she met my dad—a dashing chemical engineer who had made his way to the city from his homeland of South Africa via London. They were passionate explorers and often took my brothers and me along on their adventures. We traveled often to South Africa to visit family and took vacations to faraway places like Costa Rica, Israel, England, and Mexico. No trip was complete without time set aside to explore local markets, where we’d learn about and taste new foods and collect first-hand intel on the best down-home eateries and cafés.

When I began college at McGill University in Montreal, I had a chance to put my own knack for exploring to the test. The city offered an endless array of ethnic restaurants that lured food-loving locals and budget-conscious students alike. My friends and I slurped noodles from fragrant, brothy bowls of Vietnamese pho. At BYOB Greek restaurants, we shared plates of stuffed grape leaves, taramasalata, saganaki, and other mesmerizing meze, all washed down with bottles of store-bought boxed wine and Québec-made microbrews. We frequented the old Jewish delis of the Plateau for delectably fatty smoked meat and fresh warm bagels. At Portuguese rotisseries, we squeezed fresh lemon wedges over plates of spit-roasted chickens and potatoes slick with their delicious drippings, and ate it all up with abandon.

Late night post-bar bites included piping hot slices of thin crust pizza and, of course, poutine—the gut-busting French-Canadian junk-food specialty of French fries and cheese curds covered in a rich brown gravy—but also more exotic eats, like Lebanese-Canadian chicken shawarma sandwiches (called shish taouk) packed with pickled turnips, fresh cucumber, and tomato salad, generously drizzled with a creamy garlic sauce, and served with French fries.

Paging through the McGill Tribune one day during my senior year, I noticed there wasn’t any food or local dining coverage. I was eager to do some creative writing outside of the requirements for my anthropology and Spanish studies, so I pitched the editor on a few restaurant reviews. There was no budget for the work, but she was happy to give me the page space to fill. I wrote about cheese fondue and Peruvian ceviche, delighting in the chance to relay my foodie exploits in what felt like a somewhat professional way.

Around that time, I began cooking for myself, too, calling my mom at all hours of the day and night to get her recipes for easy basics, like roast chicken and homemade tomato sauce. After winter break, I lugged her extra food processor back to school, using it to puree fresh herbs into pestos and make ricotta cheese fillings for pasta. I bought my first kitchen “bible,” a second-hand copy of Mollie Katzen’s The Moosewood Cookbook, and happily splattered its pages with oil and spices, sauces and soups, as I cooked my way through.

When we graduated, all of my close girlfriends seemed to have their career plans sorted. I did not. No one, not even my parents, had suggested I think through next steps. I had loved and excelled at my schoolwork, which included a junior year abroad in Seville, after which I traveled through Spain, France, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, London, Prague, and Morocco. I had spent a summer living and working on a kibbutz in Israel, and another bartending in Australia and backpacking in New Zealand. My worldview had expanded exponentially through those unique and thrilling experiences, but I hadn’t taken any time to chart out my future.

Moving back home from college, I felt a little deflated. I knew I loved to write and cook, but (despite my mother’s own work in the field) it didn’t occur to me that those interests could be parlayed into a means of gainful employment until a family friend sat me down and pointed out that if what I loved most to do was to eat, write, travel, and cook, then that’s what I should pursue. Before I knew it, I was off and running.

A four-month internship at Toronto Life magazine led to a job as an editorial assistant in the lifestyle section of a new Canadian newspaper called the National Post. My work largely entailed research and fact-checking, but I took on any opportunity to write, no matter how small. Short pieces on subjects like mayonnaise taste tests and regional McDonald’s specialties around the world (did you know they used to offer lamb burgers in India?) were among my first bylines, and they made me infinitely proud. I became buddies with the food critic, who often took me along to restaurants, and the food editor, who ultimately gave me an invaluable piece of advice on how to pursue a career in food media: If I wanted to become a bona fide food writer, he told me, I needed to go to culinary school. I needed to learn how to cook, and how to eat.

I enrolled in Peter Kump’s cooking school (now known as the Institute of Culinary Education) in New York City, where I had always dreamed of living. For the final part of my coursework, I did an apprenticeship at the grande dame of the city’s classic French restaurants, Le Cirque 2000, where I had the chance not only to work with luxe ingredients like foie gras, caviar, and truffles, but also to begin to understand the level of efficiency and meticulousness (among many other traits) that a chef must possess in order to excel in the high-pressured environment of a professional kitchen. I went on to cook at Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s then-groundbreaking restaurant, Vong, where French and Thai techniques and flavors met in the form of dishes like crispy duck spring rolls and poached lobster served with paper-thin slices of daikon radish and a rosemary-ginger vinaigrette.

After 12- to 14-hour shifts at the restaurant, my fellow line cooks often went out drinking. Me? I worked myself down from the fever pitch of restaurant life by going home and reading late into the night. One book recommended to me by a friend was The Man Who Ate Everything, by Vogue magazine’s food critic, Jeffrey Steingarten, which I devoured in two post-work sittings. Jeffrey’s impassioned, authoritative and hilarious writing not only taught me innumerable food facts and kept me in stitches, it inspired my move back to media. It wasn’t ever my long-term plan to be a chef; restaurant cooking was a means to an end. Reading Jeffrey’s words made me realize I was ready to bring my hard-earned food knowledge back into the world of publishing. In true NYC-dream-story fashion, I discovered Jeffrey was looking for a new assistant and hustled my way into the job.

Working for Jeffrey was a whirlwind. No two days were ever alike, which was exactly as I had hoped. One day I’d be at the New York Public Library, researching Parisian menus from the turn of the century. The next, I’d be scouring the Asian markets and restaurant supply stores of New York’s Chinatown and the Bowery, hunting for the perfect oversized mortar and pestle and a laundry list of rare chilies and spices, galangal, and lemongrass, which Jeffrey would use to make Thai jungle curry.

We once visited nearly every restaurant in the city that had a wood-burning pizza oven, collecting data on the internal temperature of each fiery inferno with a Raytek infrared thermometer, then tested dozens of recipes for pizza dough to see whether or not we could successfully make an authentic Neapolitan pie at home. (The answer: It is entirely possible to produce a very tasty amateur version in a home oven at 500 degrees, but it will never be as ethereally crisp and perfectly burnt in spots as a pizza baked for 5 minutes at 850 degrees.)

To perfect a recipe for real coq au vin, I was tasked with finding a poultry farmer who could supply enough old roosters for us to test and re-test the classic stew every day for over a month. (Using a tough, mature male bird, as opposed to a standard chicken, is a key factor to turning out an authentic version of the dish, I learned!) Then there was the time we fine-tuned the ultimate technique for the perfect grilled steak—a feat that took over 97 days, requiring interviews with 40-some butchers and steakhouse chefs; the dry-aging of 50-plus porterhouse steaks in Jeffrey’s makeshift “aging refrigerator”; and over a dozen tastings prepared for us by a young chef named Alex Guarnaschelli and a rising star named Tom Colicchio.

Through Jeffrey, I met all of the major players in the food world—everyone from pastry master Pierre Hermé to food science guru Harold McGee, plus Ruth Reichl, Alice Waters, Martha Stewart, and chef Daniel Boulud, who—when I was ready to leave Jeffrey—offered me my next job. At the time, Daniel’s public relations and marketing team needed help, which included working on new restaurant openings, cookbooks, and events. It was a bit of a detour from my journalism track, but the opportunity to work for the most acclaimed French chef in New York, and learn the business side of restaurants, was too exciting to pass up. I now think back on my time with Daniel as my “restaurant MBA.”

Three years into the job with Daniel’s restaurant group, I was approached by Food & Wine magazine about a position on their marketing team. I jumped at the chance to put all of the food and chef knowledge I had acquired into working for a publication I had always loved and admired. Within a year I took over the management of the Food & Wine Classic in Aspen—the industry’s most prestigious annual food festival, celebrating great chefs and winemakers from all over the world. Around the same time, Bravo came to the magazine with an idea for a new reality competition show, which would give viewers a revolutionary, behind-the-scenes look at the world of professional chefs. Having done a little on-camera work for the magazine, covering recipes and food trends, I was chosen to represent Food & Wine on the show. Reality TV was in its infancy and I had no idea what to expect, but before I could give it much thought I was on my way to San Francisco to shoot Season 1 of Top Chef.

Me and mom (and a cookie)

Mom with my 3rd birthday cake, made by Aunt Sue

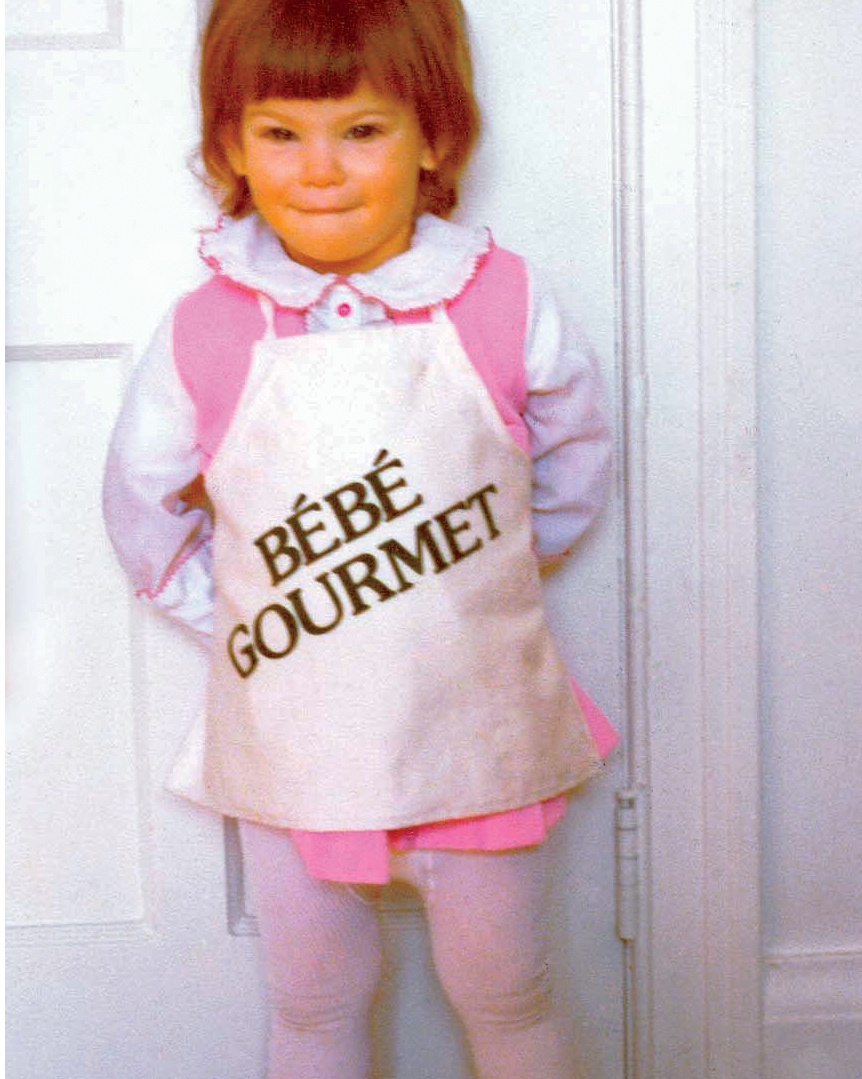

Once a gourmet, always a gourmet

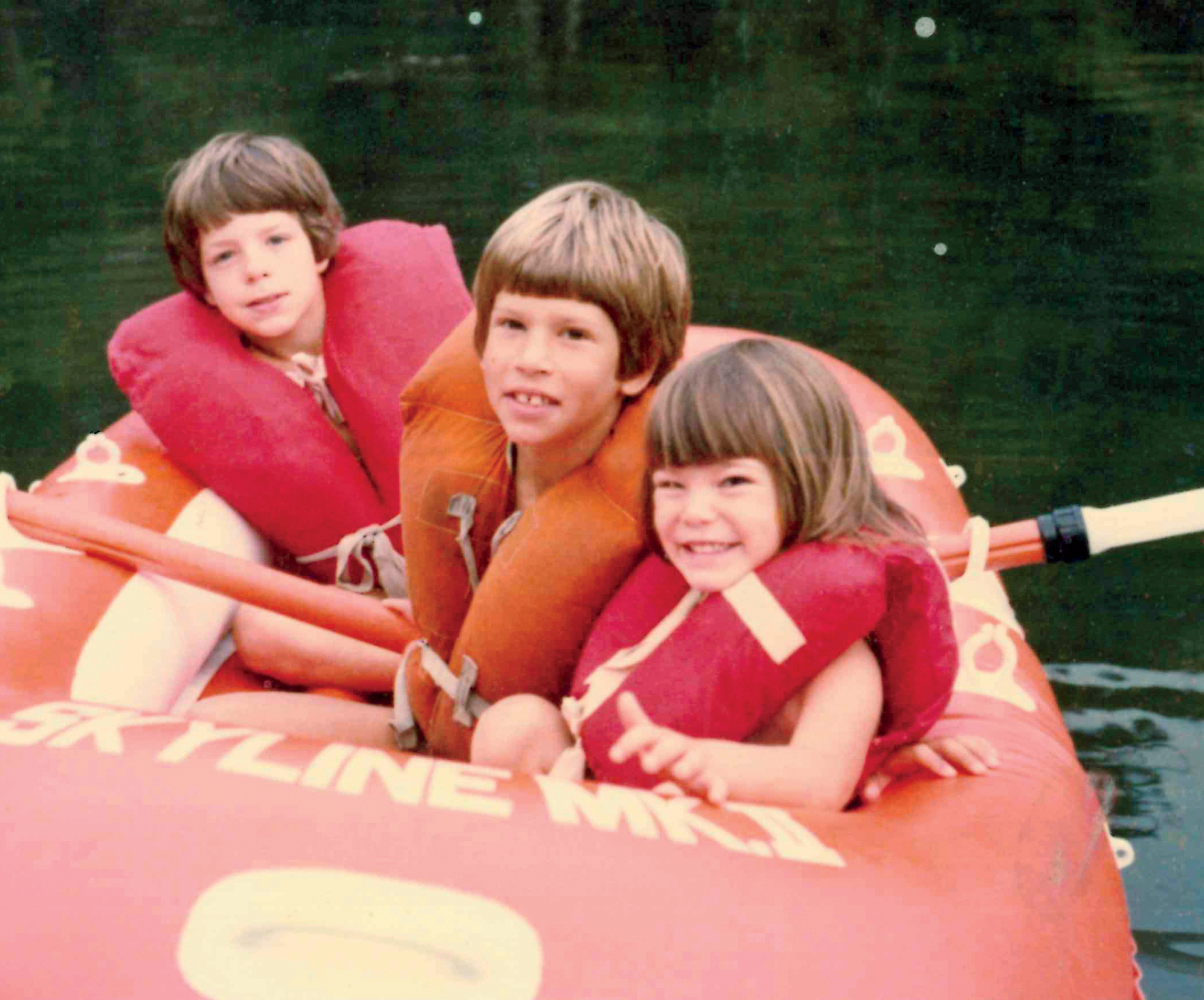

Summer days on Lake Ontario

Although I had done a fair bit of international travel growing up, I’d visited relatively little of North America before my days on Top Chef. Cities like Chicago, Charleston, New Orleans, and Austin were all new to me, not to mention places like Singapore and Hawaii. Since then—now twelve years later—my food perspective has greatly broadened, not just by spending time exploring all of these great food cultures, but also by cooking and traveling with the many great chefs and food personalities I’ve been so lucky to befriend along the way. Together, we’ve had no shortage of adventures. I’ve fly-fished in Alaska with Emeril Lagasse, Hugh Acheson, and Tom Colicchio; prepared holiday meals with Marcus Samuelsson; baked birthday cakes with Christina Tosi; and filled my belly with “smothered, covered and peppered” hash browns, late night at the Waffle House with Dominique Ansel. With these friends and more, I’ve taken pilgrimages to ramshackle food stalls and four-star restaurants in equal measure, and done deep dives into a wide array of cuisines, ingredients, and dishes—from refreshingly simple to wonderfully complex.

Every industry has a vocabulary, a jargon—doctors, lawyers, scientists, landscapers. Chefs are no different. After more than a decade at the Judges’ Table, I’ve found my role on Top Chef to be that of a translator, gathering recipes, tips, and tricks, then boiling it all down into accessible information for home cooks and food enthusiasts alike. These lessons, along with my own life experiences and travels, are my starting point for creating do-able recipes and deliciously approachable meals for my own family and friends. And that’s where this book comes in.

A noodle dish I make for my daughter, Dahlia, is a perfect example: During Top Chef’s Season 7 finale, I spent a day touring Singapore’s famed hawker centers—rowdy outdoor food courts brimming with what is arguably the best street food in the world. Along with Tom Colicchio, chef David Chang, and former Food & Wine editor in chief Dana Cowin, I was led through the city’s magnificent maze of dining options by food guru KF Seetoh, creator of the Asian culinary guide, Makansutra. Despite dozens of food stalls and the dizzying array of things we tasted that day, one dish grabbed my attention above the rest: hokkien noodles. They were made by a man who had learned his craft from his father, who had worked in the very same stall. I was mesmerized by the graceful rhythm of his cooking. Into a blazing hot wok went a beaten egg, then two types of noodles: thin rice sticks called bee hoon, and thicker, chewy udon-like wheat noodles, along with a little shrimp stock, garlic, a splash of fish sauce and soy sauce, then fresh shrimp and squid, and just a pinch of salty, fatty pork belly. The dish came together in what felt like an instant—layers of flavor, yet so simple, savory, and bright.

Back home and haunted by this irresistible combination, I failed to find an equivalent. So I made it myself using common supermarket rice noodles and an easy shrimp stock fortified with store-bought clam juice. In place of calamansi, an Asian citrus not often found in the U.S., I blended fresh lime and orange juices until I found the perfect sweet-sour balance. Bringing it home to my own kitchen table. It’s now a family favorite (and you can find it on here).

After years spent working in other people’s kitchens, and watching countless young chefs toil at their craft, I have found a cooking style I can now call my own: curious, adventurous, fresh, and easygoing. In my home kitchen, food is a celebration; a “welcome to the table” to try something new. There’s often a story or point of origin that grounds my recipes and lets my love of exploration and discovery shine through.

Over the years and especially since having a family of my own, I find myself faced with the same issues as any home cook. Most nights, like most people, I want to put a nourishing meal on the table in as little time as possible. What I’ve learned is, with a little planning, a trip to a good market or the savvy navigation of my local grocery store, and the fairly simple upkeep of a smartly stocked pantry, I can usually ace this goal. The results of my efforts are flavor-packed dishes that are accessible and delicious; a hint of the familiar, but definitely not the same old skipping-record repertoire.

In the pages that follow, you’ll find over one hundred of my favorite personal recipes. From the perfect bagel brunch with beet-cured salmon and savory cream cheese mix-ins to a recipe for eggs baked in potato skins, inspired by beach-house summers with my husband’s family; killer fish tacos with a lime crema created in homage to my favorite tortilla chip; and a sticky maple pudding cake born out of many a blustery Canadian winter. There’s my holiday brisket fried rice and my Balinese shrimp and grapefruit salad packed with chilies and herbs; a blow-your-mind spaghetti pie (see here!); and Mishmosh—a fully-loaded barley and matzo ball soup seasoned with lemon and dill, a remix of the great soups I learned from the many Jewish mothers in my life. And while I’ve made it a mission to stockpile my larder with finds from my treks the world over, I also share unique uses for basic pantry ingredients, like nut butters, coconut flakes, canned tomatoes, and common pantry spices, that will elevate your everyday cooking game.

Fly fishing in Alaska, with Emeril, Hugh, and Tom during Top Chef’s Season 10 finale

Alongside recipes, I’ve also included useful information on ingredients and techniques in Kitchen Wisdom tips to help you shop and cook with confidence, as well as tidbits of trivia that I call Snippets (a nod to a family nickname I’ve had since childhood)—fun facts that give you a broader understanding behind an ingredient or dish. Sprinkled throughout the book you’ll also find easy how-tos for professional techniques, like how to spatchcock a chicken or flash-cool potatoes to get the crispiest skins. I call them Chef Techs.

I do my best cooking at home when I approach the stove with a lighthearted state of mind and realistic expectations. When I cook at home, I’m like everyone else: I run out of ingredients (or time!); I often need to improvise, adapting as necessary when things don’t go quite as planned. At home, there’s no judging, no critical analysis. It’s just about creating easy and satisfying food for the people I love. I know that even as a confident cook it’s often trial and error when you’re cooking alone. With this in mind, I hope you’ll take this book into your kitchen and use it not only for the recipes and to learn a few new tricks, but also to help guide and encourage you to cook more often, with less of a focus on making food perfect and more on making it memorable. Along the way, may your own adventures inspire you to turn your favorite food memories into beloved dishes to bring home to your family table. Let’s dig in, together.