A horrified silence fell across the harborside as the crowd watched the masts of the three ships that had been directly beneath the cascade of stars rapidly crumble into nothing. It took many long, shocked seconds for the assorted Specters, Bogle Bugs, mummies, Grula-Grulas, Chimeras and Gragull to understand that this was actually happening for real. But as the Quayside reverberated to the hollow thud of sails and ropes falling onto decks, then the long, slow crunching sound of decks folding in under their weight like wet paper bags, people at last began to react. They rushed toward the ships and began urging the sailors to jump. Many hurried off to the Chandlery to fetch ropes and life buoys. A party of young Specters bravely leaped into the water and began hauling out anyone they could find.

Screams of “Abandon ship!” filled the harbor as the collapse began to spread along the line of ships. Masts fell like ninepins and hulls caved in like eggshells. The Harbor Master, festooned with life buoys, hurried along the Quayside, hurling them into the water, which was now dark with debris and full of struggling sailors, many of whom could not swim.

In the chaos, Daphne sneaked back to retrieve her empty woodworm box. She carefully put it in the wheelbarrow and headed toward Fishguts Twist. Daphne could take no more; she was going home. However, when she reached the stone bench where DomDaniel was slumped with his mouth open, snoring, the sight of the bag of Hallowseeth herrings was too much of a temptation. Daphne sat down and began to crunch her way through the now-cold, but still deliciously salty, little fish—heads and all. Daphne was not a delicate eater, and the noisy sucking of fish bones invaded DomDaniel’s dreams and woke him up.

Daphne tipped the remaining herring scales into her mouth, screwed up the bag and threw it angrily at a passing crocodile with an ax in its head. “I hate her,” she said.

“The crocodile?” DomDaniel asked blearily.

“No, Linda. She killed all my lovely woodworms. She’s a cow.”

For some reason DomDaniel liked Daphne. It was an odd feeling to like someone, and DomDaniel did not intend to encourage it. But he put his hand into his old cloak pocket and took out a miniature silver box inlaid with onyx. “Have you still got Dukey?” he asked.

Daphne looked stunned. “How do you know about Dukey?”

DomDaniel smiled, his lips slipping over his teeth like skin on cold custard. “I make it my business to hear what’s going on,” he said.

“Yes, I’ve still got Dukey,” whispered Daphne.

“Well, then, let’s see him.”

Bewildered, Daphne took Dukey out of her pocket. DomDaniel inspected the fat worm covered in fluff. “He’ll fit,” he said. Then he flicked the lid off the silver box, revealing a brilliant blue interior that shone like a jewel. “Drop him in there,” he told Daphne.

Dazed at such attention from the great DomDaniel, Daphne dropped her last, precious and very dead woodworm into the box. DomDaniel snapped the lid shut. “Keep it closed for twenty-four hours,” he told Daphne. “Then when you open it you will have an endless supply. You’ll soon get your colony back.”

Daphne stared at the little silver box in amazement. “Th-thank you,” she stammered.

“Don’t mention it,” said DomDaniel.

Daphne understood. “No,” she said. “I won’t.”

Daphne and DomDaniel sat in companionable silence, Daphne smiling with sheer happiness, DomDaniel worrying about why he felt as though his skin was about to fall off.

While peace descended into the shadows at the entrance to Fishguts Twist, pandemonium still reigned in the harbor. The Quayside swarmed with all kinds of creatures carrying ropes and floats and hurling them into the harbor. Some were braving the gribble worms and jumping into their own rowboats in desperate attempts to reach sailors struggling in the water. Not all rowboats made it back safely. Marcia directed her energies to Reviving those sailors who were brought out of the water half—or sometimes fully—drowned. If she got to them within three minutes of drowning, she knew she had a chance of saving them.

Simon worked hard too. Unnoticed in the melee he pulled sailors from the water and he even delivered one to Marcia without her recognizing him. Simon was near exhaustion when he caught sight of a young boy clinging on to a spar that was rapidly disappearing under gribble attack. He dived into the sludge floating on the surface of the water and pulled the boy to safety. As he helped the shivering, red-haired boy up the steps, a woman’s voice said, “Ah, poor dearie. Let me take him, Simon Heap.” Shattered, he handed the boy over. It was only some minutes later when he had recovered his breath that it occurred to Simon to wonder how the woman had known his name.

From the window in the Customs House, Septimus had watched the unfolding drama—at first with excitement at the beautiful display of lights and then, when he realized that a disaster was taking place, with frustration that he could not be down there, doing something. But he remembered what Marcia had told him and he dutifully stayed where he was.

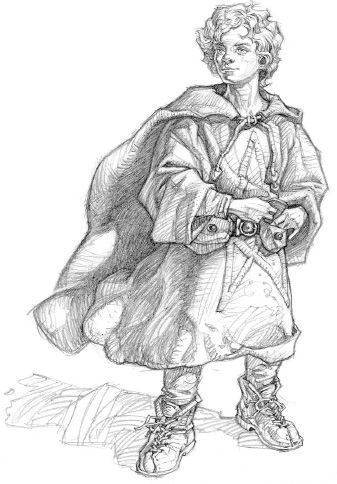

It was when Septimus saw three vicious-looking women in witches’ cloaks dragging away a struggling, half-drowned boy, that he could stand it no more. And when the boy saw him in the window and yelled, “Help me!” Septimus was off. He threw on his Apprentice cloak, buckled up his Apprentice belt and hurtled down the stairs. But by the time he got outside, the boy and the witches were gone.

Marcia’s final Revive had worked. The sailor sat up and groaned. “You’ll be okay,” she told him, helping him to his feet.

“I’ll get him along to the Harbor Master’s,” said Alice. “They’re opening the emergency bunkhouse out the back.”

Marcia watched Alice help the bedraggled sailor slowly across the Quayside. She turned and looked at the harbor. The water reminded her of one of Aunt Zelda’s stews—thick, brown and full of white stringy things. It was, in fact, now more of a rubbish dump than a harbor. The remains of thirteen ships—mainly a tangle of ropes, sails and fishing nets—floated in a thick scum of gribble-digested wood dust. A somber crowd of Port people had gathered and were hugging one another in dismay. Not only were all thirteen ships gone, but the harbor itself was now unusable. Below the watery sludge lay the ironwork from thirteen ships piled onto the harbor bottom, along with, they feared, the remains of more than a few drowned sailors. Marcia joined the onlookers. She felt powerless to do anything to help. No Magyk could help the drowned now, or restore the ships. Marcia shook her head in dismay—the Port Witch Coven had done a terrible thing.

Suddenly she heard a voice calling, “Marcia!” She spun around to see Septimus racing toward her. “Septimus, I told you to stay inside,” she said, trying—unsuccessfully—to be stern and not show how pleased she was to see him.

“I’m sorry,” said Septimus, “but the witches … they …” He stopped to catch his breath.

“I know,” said Marcia. “It’s awful.”

“They … kidnapped a boy.”

Now at last there was something Marcia could actually stop them doing. “Right, let’s get them,” she said. “Which way did they go?”

Septimus pointed toward Fishguts Twist. “Up there. I think.”

They stopped by an empty bench at the mouth of Fishguts Twist. The alleyway had numerous branches off it—or dives, as they were called in the Port.

Septimus eyed the dives despondently. “But they could have gone down any of those,” he said.

Marcia was unwilling to give up. “So we’ll just have to take our chances.”

It was at that moment that the Darke Toad’s Listening Time was up. It hopped out from the drainpipe and the movement caught Septimus’s eye. “Oh!” he said. “It’s a toad.” To Marcia’s disgust Septimus squatted down and picked it up. The toad sat in his hand and stared balefully at him. Septimus stared back, remembering a rude rhyme about DomDaniel they used to whisper in the Young Army:

If you want to know where DomDaniel sat,

Go where it smells of rotting cat.

If you want to know where DomDaniel’s gone,

Find a fat toad and you won’t go wrong.

Because wherever he goes

There is always a toad.

Just follow the toad in the road.

The Darke Toad shifted uncomfortably on Septimus’s hand. It didn’t like the feel of human warmth one bit.

“Put that horrible thing down, Septimus,” said Marcia. “You don’t know where it’s been.”

“But I do know where it’s been,” said Septimus.

“Up some disgusting drainpipe, no doubt. Put it down.”

“It’s been with DomDaniel,” said Septimus.

There was something about Septimus’s certainty that made Marcia take notice. “Really?” she said.

“I reckon,” said Septimus, raising his hand to his face so that he and the toad were eyeballing each other, “that this is a Darke Toad.”

“Most Port toads have some Darke in them,” said Marcia. “We have the Port Witch Coven to thank for that.”

“But this is a DomDaniel toad,” said Septimus. “I’m sure it is.”

Marcia looked puzzled. “How do you mean?” she asked.

“Well, they used to say that DomDaniel always took a toad with him when he went anywhere. When he left, he’d leave it there as a sort of spy. The toad would hang around for, er—” Septimus trawled his photographic memory and scrolled down page three of his old Young Army Memory Book. “It was 5.71666666666667 minutes, I think, to listen to what people said about DomDaniel after he left, then the toad would catch up with him and tell him. It got a lot of people into big trouble. When I was in the Young Army we were taught to recognize a DomDaniel toad. And not stamp on it. Ever. We had signs stuck up in the barracks saying Respect the Toad.”

“So you mean that this one will hop off now and tell DomDaniel what we’ve been saying?” asked Marcia.

“I reckon so,” said Septimus.

“Well, it can tell him from me that I know he’s at the bottom of this and he is not getting away with it. It can tell him from me that I’m coming to get him.”

But it was not DomDaniel who concerned Septimus; it was the Port Witch Coven. “Marcia, Alice Nettles said that DomDaniel was with the Port Witch Coven, didn’t she?”

“Well, yes, she did. I must admit, Septimus, I did think she was mistaken, but maybe she was right after all. Well, there’s only one way to find out. Let the toad go and we’ll follow it.”

Septimus put the toad onto the ground and it quickly hopped away. “Just follow the toad in the road,” he murmured.

Marcia looked at her Apprentice quizzically. “Another Young Army rhyme?” she asked.

“Well …” Septimus always felt reluctant to admit to remembering anything from the Young Army. It felt somehow disloyal to Marcia.

But Marcia was not concerned at all. She smiled. “There was a surprising amount of sense in some of their rhymes,” she said, “Come on, Septimus, let’s go.”