14

Taking Stock of Broth

Most self-respecting chefs would say that the only proper thing to do is to make the stock yourself. Or at least few would admit taking the shortcut of popping in a couple of bouillon cubes in their sauce or stew (“broth” and “bouillon” are used more or less synonymously even though “bouillon” is also used for the dehydrated cubes and powders. “Stock” is used for a more intense version where broth/bouillon has been simmered down. Broth and liquid bouillon can be used as dish in itself, while stock is considered an ingredient). Stock is made by quite humble and inexpensive ingredients, and the procedure is quite straightforward, dissolving flavor from meat, bones, vegetables, and herbs into hot water. Or is it really? Professor Hervé This, who has spent years collecting thousands of claims about cooking, found that cooking stock is among those processes that have the highest number of claims and rules connected to it in the French tradition. Stock is the cornerstone of French cuisine, the foundation that the rest of the course is built upon. While you make your stock, you will meet several points calling for you to make one or more choices: should you put the meat and bones in cold or hot water? Is the lid to be on or off the pot? Should you add the spices now or later? And so it goes.

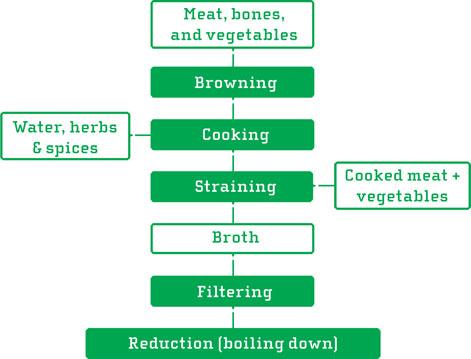

Although the classic way of cooking a brown meat stock makes use of modest ingredients, it takes a certain amount of labor and extended time. Following a five-step procedure, cooking a stock of “restaurant quality” may take a couple of days, often having the process going on overnight. The meat bones for such a stock would normally be beef or veal and classic vegetables are onions, carrots, and celery, called mirepoix in French. The herbs are usually parsley, bay leaves, thyme, a bouquet garni. You brown the meat bones and vegetables in a pan or oven to achieve the color and complex flavors from Maillard and other reactions. You then add water, herbs, and spices and let it all simmer for a certain amount of time while skimming off proteins and other components rising to the surface as a foam, and then strain it to get a rather dilute and bland-tasting broth. You then let it simmer or boil while skimming until it has reduced to a certain volume and developed a rich flavor and golden-brown color (see figure).

^Main steps in making stock, adapted from Snitkjær (2010)

Stock making is not very different today than as it has been described in cookbooks throughout the last several hundred years. Why not? Perhaps because the old methods do indeed produce a very good result and thus there have not been a pressing need to change the procedure? Or maybe out of respect, or fear, of the old culinary masters? On the other hand, this way of thinking may also prevent possible progress. What if we had used this approach to the introduction of the printing press, the television, the personal computer, or the motorized car? All were met with claims that they were not necessary, or even good, for humans. Hasn’t science done anything to help us learn more about the time-consuming process of making stock? Science and technology have given us the bouillon cube but have apparently not produced much new knowledge or technologies that has reached home – or restaurant kitchens for making stock from scratch. Hervé This has stated that food science has traditionally been mostly concerned with the agricultural and industrial sides of food and not found the activities of the kitchen, be it in a restaurant or at home, worthy of scientific study. That is, until the 1980s and the introduction of the branch of food science termed molecular gastronomy. Perhaps the apparent lack of interest in cooking practices, from the side of food science, is an explanation for why stock making hasn’t changed much while the societies around it have changed radically?

If the chef was to embark upon comparison experiments along the five-step process of stock making with 8–10 different ingredients, she or he would end up with a vast number of possible parallel stocks to be made and compared. You may vary the type of meat, the amounts and types of vegetables, herbs, and spices, the point of addition of the vegetables and herbs/spices, browning or not browning the ingredients, starting with hot or cold water, the cooking time, cooking temperature, leaving the lid on or off, the reduction time, and probably more. Testing all these would indeed result in around 8000 parallel stocks to be cooked! For one single cook or team to carry out all these parallels is probably the project of a lifetime unless s/he had an automated research lab at hand. At least, it would probably be impossible to accomplish such a task manually and, at the same time, run a restaurant. Surely, many variations have already been tested since we today have some classical recommended procedures, vegetables, herbs, and spices to go into a stock. After all, many chefs have most likely tested and rejected many versions to find them less important or palatable. And the rejected versions would usually not end up in cookbooks.

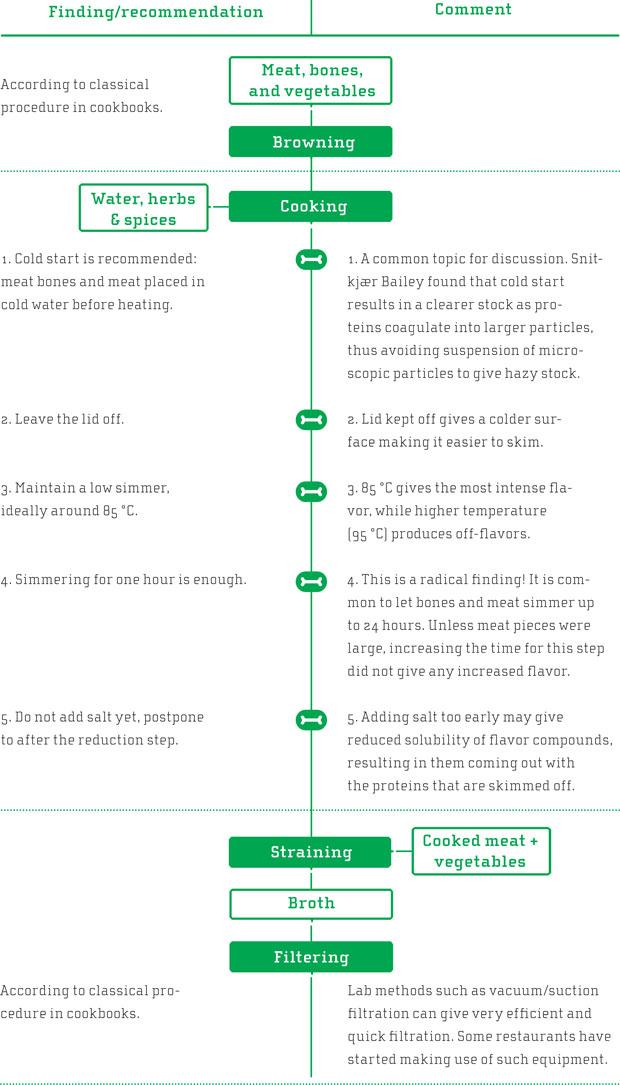

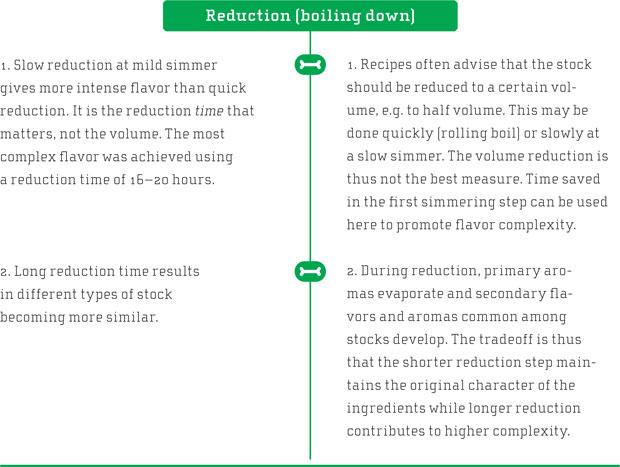

Thanks to the recent field of molecular gastronomy and The University of Copenhagen finding this field worthwhile as investing in, the food scientist Pia Snitkjær Bailey could spend some years working with meat stock. Indeed, she wrote her whole doctorate on the topic and revealed some surprising findings. Her thesis was divided into two parts: (1) the process and steps in cooking meat stock; (2) the effect of red wine in cooking meat stock. In her research, she obviously had to delimit her studies to focus on a few parameters to finish her thesis in time. But considering the interesting results that came out of it, her choices seem to have been very good. The findings that seem to be most surprising to experienced chefs are the impact of cooking times for the two boiling steps. Her results may indeed have a major impact on both time consumption and organization of this important activity in a restaurant. And it is definitely useful if you want to make your own stock at home. A summary of some of her findings with focus on procedure is given in the table above.

^The figure shows the steps of cooking stock together with recommendations and comments for each step. Based on the studies by Snitkjær Bailey (2010)

It is an interesting reflection for us that, just as in the case of cooking eggs in water, this research had not been done earlier. After all, it is about a practice that is carried out in thousands of restaurants and homes across the world every day, and the research provides knowledge that may change those practices in fundamental ways. If only these stock-makers had all been aware of it. Surely quality science communication may be an important activity.

Making a red wine sauce. There are at least two basic ways to make a red wine stock.

1. You reduce a mixture of wine and chopped onions. Add meat stock prepared beforehand and continue reducing until you are satisfied.

2. Add red wine to your broth after the straining step and let them reduce together from the start.

If you are running a restaurant, the first approach may be convenient since you can have a basic meat stock that is used in various ways – with or without wine. If you make stock for a single meal at home, you could choose the one you find most convenient.

Pia Snitkjær Bailey wanted to examine how red wines with different flavor characteristics affected the flavor of the stock. And since tannins react with proteins upon heating, she was also interested in studying how red wines with different tannin levels affected the meat proteins. She analyzed ten different stock samples based on beef stock combined with two different wines chosen for their different tannin levels: a Cabernet Sauvignon (high in tannins) and a Zinfandel (low in tannins).

She found that the aroma of the red wine was to a large degree lost in the reduction step. This is quite self-evident because volatile substances, which are those reaching our nose, evaporate easily. After all, if they didn’t evaporate we wouldn’t be able to smell them. The advice is, therefore, that wine for cooking should not be chosen based on its aroma, but rather on its mouthfeel and taste, such as sweetness, acidity, and astringency (the drying sensation in the mouth imparted by tannins). So, if you want to make an effort choosing a wine for your sauce, hold your nose while evaluating it. This would probably require that you are an experienced taster and sauce maker, however. Consequently, the most expensive wines are most likely wasted in a sauce.

Tannins from red wine and proteins from meat stock react to precipitate, complex, insoluble substances. If the meat stock and wine are reduced separately and thereafter combined, the result might therefore be a slightly grainy/sandy mouthfeel. Snitkjær Bailey also reported that this procedure led to a more astringent and perhaps bitter sauce. Therefore, reducing the meat stock and wine together gives a less astringent sauce than that made by reducing stock and wine separately. Not surprisingly, this effect is more pronounced when using a wine rich in tannins. If you still choose to reduce stock and wine separately, you may combine them and reduce for 30–45 minutes and finish it off by a filtration to avoid the risk of a slight grainy and astringent mouthfeel.

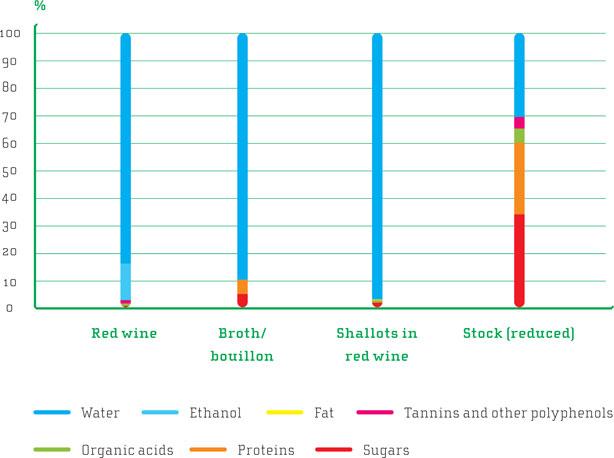

^Before reduction, red wine and broth is mostly water. After several hours’ reduction, the water content is reduced from the original 90% to 25%. At the same time, the concentration of non-volatile compounds such as sugars, acids, and amino acids increases markedly. In addition, numerous new substances are produced as result of chemical reactions.

A fine wine experiment Red wine sauce, similar to, for example, puff pastry and some other products, is a laborious ingredient where the industrially prepared alternatives may be competitive for the occasions where you don’t have time to carry out all the time-consuming steps. Although maybe a disappearing skill in home kitchens, we were inspired by Snitkjær Bailey’s work and decided to have a closer look at what happens in the pan during the reduction step in one of our food workshops. We were curious to see with our own eyes, and taste with our own palates, which roles the red wine could play in the sauce.

The point of departure was a basic recipe for red wine sauce: take half a liter of good meat stock and half a bottle of red wine and reduce it down to one deciliter. The procedure is not ideal according to Snitkjær Bailey’s research, but the approach would give us two stocks that would be directly comparable in terms of reduction time. To which degree would the characteristics of the wine affect the flavor of the final product? Would minor differences in acidity, sweetness and mouthfeel in the wines show up in stocks cooked for several hours? If so, how are the differences experienced?

We prepared three different red wine stocks with three different red wines with increasing body, aroma intensity, and amount of dry extract: a light Beaujolais, a medium-bodied Rioja, and a full-bodied Argentinian Malbec. The differences in acidity, sweetness, and body were clear but not dramatic. For example, the acidity varied from moderate (5.0 g/l total acids in the Beaujolais) to high (5.7 g/l total acids in the Malbec). The dry extract is the amount of solids left when all water is evaporated and gives indications towards the quality and body of the wine. In these wines, this parameter varied between 24 g/l in the light-bodied Beaujolais to 35 g/l in the full-bodied Malbec. The Rioja was in between these two extremes both in acidity and dry extract content. Would these differences reflect in the stock when tasted by the panel consisting of workshop participants?

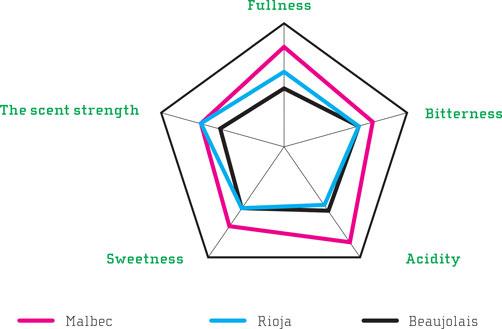

The sauces were cooked, coded, and served as blind samples for the tasting panel. The differences in sauces were obvious already to the naked eye. The Beaujolais came out lightest, the Malbec darkest. The participants were asked to rank the three sauces in order of increased body, bitterness, acidity, sweetness, and aroma intensity. The values were summarized and displayed as a radar diagram often used in sensory science to visualize how the different characteristics were evaluated by the panelists.

^Results of red wine stock blind tasting (panel of 12 participants): The radar diagram shows that the three wines gave stocks with very different sensory characteristics.

The differences in the three red wine sauces were quite obvious, and there was no question about the important role of wine in cooking (see diagram). The full-bodied Malbec gave, except for aroma intensity, a stock with more of everything: body, acidity, sweetness, and bitterness. The Rioja gave a stock that was fairly similar to the one with the lightest of the wines, but somewhat more body and clearly higher aroma intensity. The result was quite unambiguous: the wine makes the sauce!

Naturally, we also asked the question that most choose to ask right away: which stock would you prefer? Liking is always a matter of personal taste and more or less up for debate. In this case, nine out of 12 participants considered the stock made with the full-bodied Malbec as the best, the three remaining preferring the Rioja-based stock. However, this time, the liking-issue raised some harmonious debate among the participants. Everyone agreed that a sauce should match the main ingredient of the dish and that it cannot be evaluated alone. Every dish requires its own tailored sauce.