Spanning 118,000 sq miles (306,000 sq km), and with elevations ranging from 70ft (21 meters) above sea level at Yuma to 12,643ft (3,854 meters) at Humphreys Peak near Flagstaff, Arizona is much more than the searingly hot desert flats, saguaro cacti, and howling coyotes of popular myth. In fact, it is the most biologically diverse state in the American Southwest, with 137 species of mammals, 434 different species of birds, 48 snake species, 41 lizard species, 22 types of amphibians, thousands of arthropods, and a stunning 3,370 species of plants.

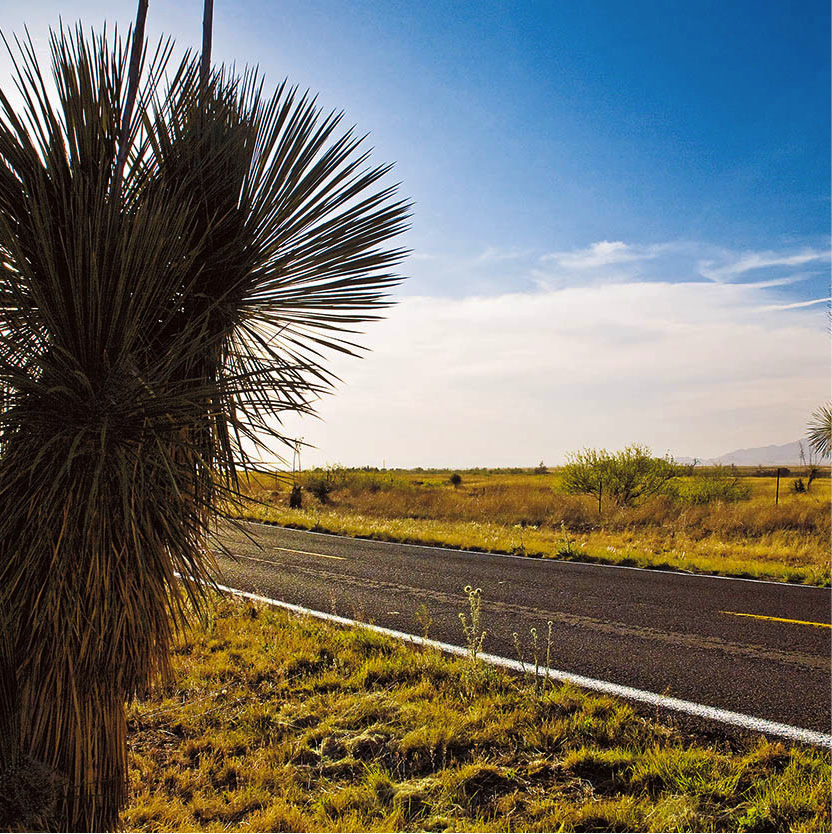

Joshua tree cactus (Yucca brevifolia) growing alongside Desert Marigold (Baileya multiradiata).

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

Such diversity can be attributed to the state’s wide range of habitats, which include four converging deserts – the Sonoran, Chihuahuan, Great Basin, and Mohave – basin-and-range topography, and unusual ecozones, from lava flows to caves, where species have had to make special adaptations. In addition, a large number of plants and animals have migrated permanently north of the US–Mexico border to occupy protected niches in riparian corridors.

Only one of Arizona’s 30 scorpion species, the bark scorpion, is considered life-threatening, though no deaths have been attributed to the species in the state for more than 30 years.

This is remarkable because when one thinks about Arizona, one instantly thinks of aridity. The Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona is found at the 30th parallel north of the equator, which creates atmospheric circulation patterns that lead to desertification. Another leading factor is that Arizona is a long way from the coast, too far to benefit from moisture. Moreover, any coastal moisture it might have received is effectively blocked by California’s 14,000ft (4,300-meter) Sierra Nevada, placing the Grand Canyon State in a rain shadow. Even high-elevation areas often receive less than 15ins (38cm) of precipitation a year – the high desert range.

Rattlesnakes are often found under rocks, logs, and other protected places.

iStock

Precious water

Finding and holding on to water is what life is all about here, especially for those plants and animals that, unlike people, birds, and larger predators such as wide-ranging coyotes and mountain lions, cannot leave. Desert plants and animals have developed strategies for survival. The kangaroo rat gets all its water from seeds. Spadefoot toads encase themselves in slime in the bottom of dried-up potholes, or tinajas, and wait months for heavy rains. Cacti gave up leaves in favor of protective spines and large water-saving waxy trunks that also help them photosynthesize food.

“In the desert … the very fauna and flora proclaim that one can have a great deal of certain things while having very little of others.” – Joseph Wood Krutch, The Desert Year.

The lay of the land

The southern part of the state is “basin and range”, a land of craggy, young volcanic mountains that form verdant “sky islands” above huge desert basins and ephemeral playa wetlands, such as those around Willcox, that attract thousands of migratory waterfowl each winter. By contrast, northern Arizona’s Colorado Plateau soars from 5,000 to 12,000ft (1,500–3,600 meters) in a sprawling high country of volcanic peaks and uplifted plateaux, expansive ponderosa pine forest, glittering lakes, alpine meadows, and sandstone canyons carved by the Colorado River and its tributaries. In between, at 3,500 to 5,000ft (1,100–1,500 meters), are sweeping grasslands around the fast-growing communities of central Arizona’s Payson and Prescott and the US–Mexico border around Patagonia (Arizona’s historic cattle country), transitioning to pinyon-juniper dwarf forest between 5,500 and 7,000ft (1,700–2,100 meters) in areas like Sedona on the Mogollon Rim.

Desert plants employ such formidable defences as spines and bitter-tasting or bladelike leaves.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

Desert blooms.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

Most of southern Arizona is in the Sonoran Desert, at 10,000-years-old a relatively young desert, averaging 3,000ft (900 meters) in elevation, that slices diagonally from the southwest quarter of Arizona down to the Sea of Cortez in Sonora, Mexico, as far as the Sierra Madre in the east and the lower southeast corner of California in the west. Because of its location, the Sonoran receives moisture twice a year – summer “monsoons”, as they are dubbed (incorrectly), from July to September, and winter storms – making it the greenest of the West’s deserts.

In the drier western Sonoran Desert, around Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, dominant plants include foothill paloverde, saguaro, cholla, and ironwood; in areas with more moisture, such as the Arizona Uplands around Tucson, add to the mix blue paloverde, mesquite, catclaw, desert willow, and desert hackberry, and shrubs such as bursage, creosote, jojoba, and brittlebush. When previous summer and early winter rains have been adequate, the Sonoran no longer seems a desert but a flower garden, with poppies, brittlebush, desert marigolds, lupines, fairyduster, fleabane, and other beauties blooming in waves, beginning in February.

A lush desert

More than 100 species of cactus call the Sonoran home, including organ pipe, Mexican senita, cholla, pricklypear, beavertail, pincushion, claret cup, hedgehog, and the symbol of the Sonoran Desert: the many-limbed saguaro. Cacti like these are the most successfully adapted of all desert plants. They take advantage of infrequent but hard rains by employing shallow root networks to suck up water, which is then conserved, accordion-like, in the gelatinous tissues of their waxy trunks. Cacti use their broad trunks to photosynthesize sunlight for food and have modified leaves into spines, which are much more useful as protection.

Cacti use their broad trunks to photosynthesize sunlight.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

Three-quarters of desert animals are nocturnal. Your best chance of close-up encounters is to visit a water hole in the cool dusk or dawn hours, or visit the sprawling Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, west of Tucson, where naturally landscaped enclosures house rarely seen mountain lions, bobcats, and jaguarundis, kit foxes, desert bighorn sheep, and black bears, as well as the utterly charming coati, a type of ring-tailed cat from south of the border that likes to curl up in a ball in a tree and snooze during the day. Most visible are squirrels and crepuscular hunters and browsers like large-eared mule deer and bands of javelina, or desert boar, which congregate along sky island backroads and feed on prickly pear cactus fruit in late summer. Javelina, with their little tusks and stout bodies, are delightful to encounter as you drive the desert, but they have poor eyesight and can charge if threatened. Don’t approach them.

Blossoms are often large and brightly colored.

iStock

More than 400 species of birds live in the Sonoran Desert and include the topknotted Gambel’s quail, roadrunner (the state bird), mourning dove, phainopepla, and birds that carve out cool nests in saguaro trunks, such as the Gila woodpecker, northern flicker, cactus wren, curved-bill thrasher, and elf owl. Birds of prey and other avian species that can move easily from shade to sun are visible in daytime desert skies soaring on thermals. Often spotted are Harris’s and red-tailed hawks, peregrine falcons, and golden eagles on the lookout for darting jackrabbits, cottontails, or ground squirrels.

Be careful where you walk and put your hands during daytime hikes. Mottle-skinned rattlesnakes, brightly hued collared lizards, whiptails, chuckwallas and the impressive-looking Gila monster keep cool under rocks and bushes during the day. Lizards have a variety of strategies to evade capture, including detaching their tails when caught and later growing a new one. Gila monsters can live for several years on fat stored in their tails.

The common raven, the subject of much Native American folklore, is extremely intelligent and displays complex social behavior.

Getty Images

An unforgiving environment

Parts of southeastern Arizona are in the Chihuahuan Desert, two-thirds of which is found in Mexico. At a mean elevation of 3,500 to 5,000ft (1,100–1,500 meters), this desert has relatively long, chilly winters, with occasional snowfalls that melt quickly. As with the Sonoran Desert, summer temperatures in the Chihuahuan exceed 100°F (38°C) but are cooled by violent summer monsoons, which drop 8–12ins (20–31cm) of annual rainfall in places like Bisbee, Tombstone, and the Willcox Playa area. Limestone caverns, such as those at Kartchner Caverns State Park near Benson, are found in this area, which was inundated by a Permian Sea 250 million years ago. Ocotillo, prickly pear, and cholla cactus do well in these calcium-rich soils. The signature vegetation of the desert is the lechuguilla agave, which has thick spikes rising from a rosette of fleshy, swordlike “leaves.” After exiting the Mule Mountains tunnel, north of Bisbee, watch as the Chihuahuan Desert starts to blend with the Sonoran, with ocotillo and agave neighboring with saguaro.

Giants of the Desert

The many-armed saguaro cactus seems as timeless as the Sonoran Desert it inhabits. Indeed, saguaros may live for more than 150 years, given warm southern exposures and sufficient rain on mountain slopes, or bajadas. They don’t even begin to grow their appendages until they are 75 years old. Their shallow roots suck up moisture into barrel-like torsos that swell like an accordion, storing as much as 200 gallons (750 liters).

Saguaros take summer highs in excess of 100°F (38°C) and freezing winter temperatures in their stride. Spines protect them from intruders, trap cool air, provide shade, and along with the cacti’s waxy coating, protect them from dehydration. Unlike leafy plants, saguaros photosynthesize food along their arms and trunks, the latter often reaching 35–40ft (11–12 meters) in height. In spring, saguaros sprout white blossoms that attract visiting Mexican long-nosed bats, which pollinate the cactus with their wings as they sip nectar. In late summer, saguaros sport ruby-red fruit that, for centuries, have been made into syrup and jelly by the Tohono O’odham. Their ancestors made shelters from saguaro ribs, glue from the flowers, and treated arthritis with saguaro poultices. Urban sprawl, pollution, and vandalism threaten saguaros. Millions are protected in the two units of Saguaro National Park, outside Tucson.

Mohave and Great Basin

The Mohave Desert extends into Arizona along the Colorado River on Arizona’s western border. The least colorful and most overheated of all the deserts in summer, the Mohave can transform overnight into a wildflower extravaganza with enough rainfall. Ironwood, desert holly, creosote, blackbrush, and bursage are spaced evenly to take advantage of available moisture. The indicator species here is the shaggy Joshua tree, a giant yucca named by Bible-minded Mormons passing through in the 1800s. Relict palm trees have found a niche in a canyon in the Kofa Mountains, along with a thriving population of endangered desert bighorn sheep. A herd of about 500 bighorns lives in Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, on the US–Mexico border. Every June, as temperatures soar, volunteers count the sheep – the true calling of “desert rats.”

Wildflowers bloom.

iStock

The northwestern corner of Arizona is primarily Great Basin desert, which extends all the way to eastern Utah and Oregon. A cool desert, found at elevations of 4,000ft (1,200 meters) or higher, the Great Basin was once dominated by lush, tall native bunchgrasses such as Indian rice grass, sideoats, and blue grama. Today, most of these native grasses have given way to disturbance species such as sagebrush, saltbush, snakeweed, rabbitbrush, and the ubiquitous cheatgrass after more than a century of grazing by cattle and sheep. Grasslands in protected parcels of southern Arizona like Las Cienegas National Conservation Area are beginning to recover.

Animal magnetism

Arizona’s southern desert “sky islands”, with their higher elevations and thick stands of evergreen-deciduous forest, are a powerful magnet for living things trying to escape the heat of the desert. For every 1,000ft (300 meters) gain in elevation, the temperature drops 4°F (2°C) and precipitation increases about 4ins (10cm). In the sheltered canyons of the Chiricahua and Huachuca Mountains, near the Mexican border, Arizona cypress and alligator juniper mingle with Mexican natives like Chihuahua and Apache pine, while at higher elevations, Douglas fir, aspen, and ponderosa pine provide food for white-tailed deer and cover for sulphur-bellied flycatchers, Mexican chicadees, and long-tailed elegant trogons.

Wildlife (and human residents) in the desert borderlands are particularly drawn to cool riparian areas, where perennial streams offer that most precious of gifts: reliable water. Southeast of Tucson, places like Ramsey Canyon in the Huachucas and Madera Canyon in the Santa Ritas are oases, attracting 14 of 19 hummingbird species that winter in Mexico and nest in the huge sycamores, maples, and oaks that line the creeks.

San Pedro River is one of the country’s most important waterways, protecting cottonwood-willow bosques for hundreds of resident birds and literally millions of migratory waterfowl, such as sandhill cranes and snow and Canada geese, which also use flooded desert basins, or playas, in Sulphur Springs Valley, near Willcox in southeastern Arizona. In northern Arizona, bald eagles are often found wintering on alpine lakes and reservoirs near Flagstaff, where cold-water fish are plentiful.

Northern uplands

Glorious though southern Arizona’s desert mountains are, the most spectacular area of Arizona is the canyon country of the Colorado Plateau, the uplifted region north of the Mogollon Rim that takes in the White Mountains, the San Francisco Peaks, and the Coconino and Kaibab plateaux of the South and North Rims of the Grand Canyon. The largely sedimentary layers of the monolithic Colorado Plateau began to be pushed up by faulting in the mid-Cretaceous period, some 75 million years ago. The area continues to rise and has been further uplifted and sculpted by local faulting into breathtaking high peaks and plateaux.

The Colorado River has carved canyons through the uplifted plateaux creating the Grand Canyon, an abyss that drops from an elevation of 8,200ft (2,500 meters) at the North Rim to 1,300ft (400 meters) at the Colorado River. This kind of sudden elevation change has created a unique situation for wildlife, which has had to adapt to vastly different environments, from desert to montane, and corresponding changes in temperature, moisture, soil type, slope angle, and exposure to sun and wind.

The bottom of the Grand Canyon is as torrid as the Lower Sonoran Desert in summer, with temperatures exceeding 100°F (38°C). Life concentrates along the river, where willow and tamarisk form bowers for large numbers of songbirds, including the endangered Southwest willow flycatcher. Small canyon wrens flit around the rocks, their presence announced by their haunting descending songs.

It’s a different story on the rims. Huge, airy forests of ponderosa pine and Gambel oak sweep across the Coconino and Kaibab plateaux, forming the largest ponderosa forest in the continental United States. The forests are home to Steller’s jays, mule deer and two species of tassel-eared squirrels, the Aberts of the South Rim and Kaibab of the North Rim, whose destinies diverged millennia ago, when the Grand Canyon separated them. In high country, black bear are common, though grizzlies no longer roam the peaks. The last grizzly, nicknamed Bigfoot, was sighted on Escudilla Mountain near Springerville, in the White Mountains, in the 1930s.

Return from the brink

A number of endangered species are now once again roaming their natural habitats in Arizona. California condors were successfully introduced to the Arizona Strip area, 30 miles (48km) north of the Grand Canyon, in 1996, after a 10-year captive breeding and release program guided by the Arizona Game and Fish Department, federal wildlife and land management agencies, and private conservation groups. California condors are the largest land birds in North America, with a wingspan of more than 9ft (3 meters) and weighing up to 22lbs (10kg). Members of the vulture family, they are opportunistic scavengers, feeding exclusively on carrion, traveling 100 miles (160km) or more per day in search of food. The birds managed to maintain a strong population until the settlement of the West, when shooting, poisoning from lead and DDT, egg collecting, and general habitat degradation began to take a toll. Today, they may often be seen soaring over Marble Canyon and House Rock Valley in northern Arizona.

Coyotes prey mostly on small animals but will eat just about anything.

iStock

The reintroduction of the endangered Mexican wolf remains controversial. Mexican wolves once ranged from central Mexico to West Texas, southern New Mexico, and central Arizona, but by the mid-1900s had been virtually eliminated from the wild by ranchers concerned about livestock predation. Since March 1998, numerous packs of radio-collared wolves have been released into Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest in eastern Arizona, on the Arizona−New Mexico border. As of late 2014, 19 packs containing a total of 109 wolves had been counted in the wild; more than 300 wolves are being held in captive-breeding facilities throughout the US.

Other reintroduction efforts include a black-footed ferret breed-and-release program in the Aubrey Valley, in northwestern Arizona, and the release of endangered Sonoran pronghorn antelope in the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, southwest of Tucson.

Arizona’s State Reptile

Arizona offers prime habitat for rattlesnakes (which can be found on some menus in the state); 13 of 36 identified species of rattlesnake are found in Arizona, including western diamondback and massassauga rattlesnakes, more than any other state. The state’s official reptile since 1986 is the relatively unvenomous Arizona ridge-nosed rattlesnake, a small, primitive, brown rattlesnake only found in the Santa Rita and Huachuca Mountains of southern Arizona. The rattle that serves as a warning of a rattlesnake’s presence is a segmented keratinous extension of the tail.