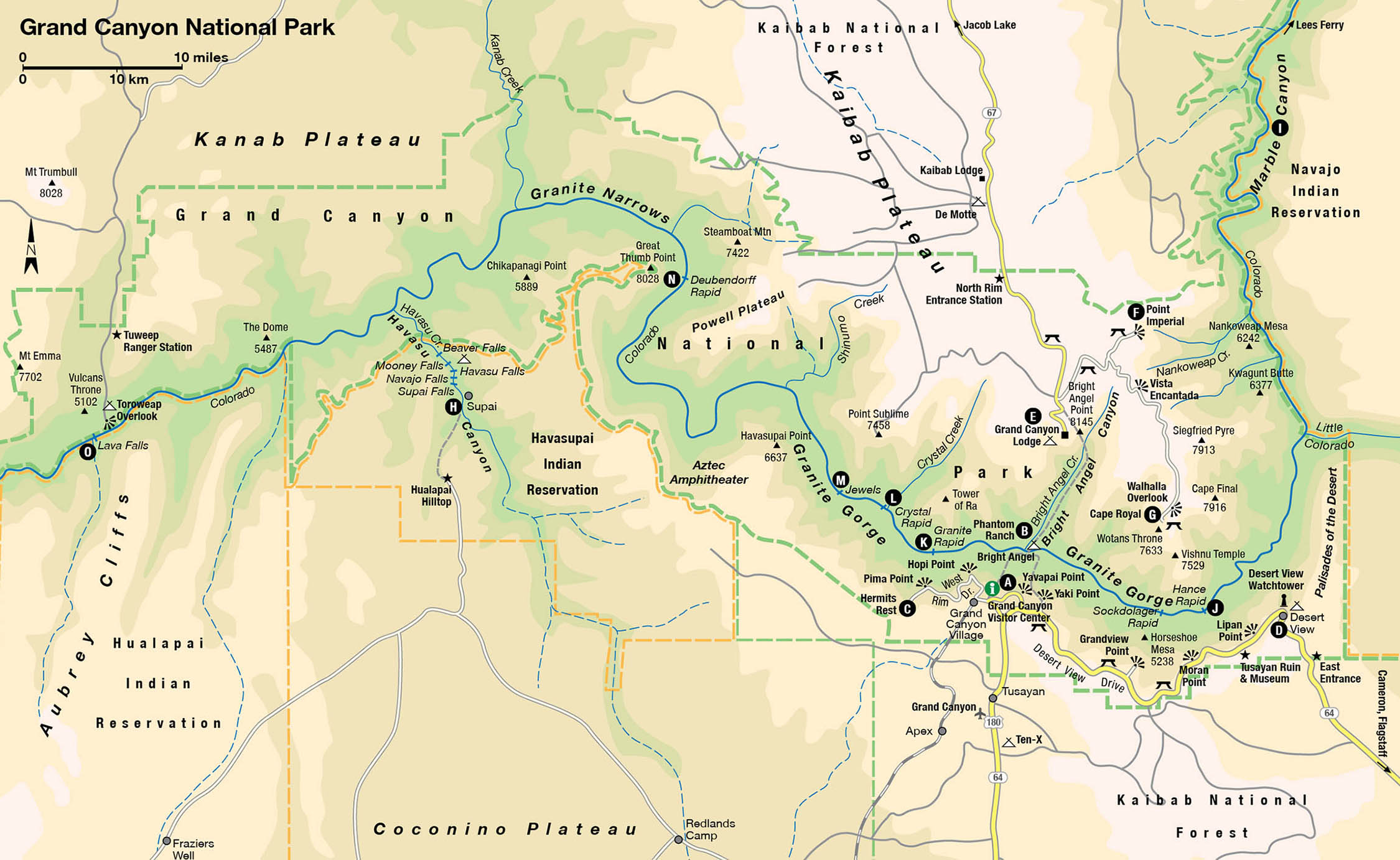

The ancients spoke of the four basic elements of earth, water, wind, and fire. But at the Grand Canyon 1 [map], another element must be added – light. It is light that brings the canyon to life, bathing the buttes and highlighting the spires, infusing color and adding dimension, creating beauty that takes your breath away. Sunrise and sunset are the two biggest events of the day. In early morning and late afternoon, the oblique rays of sunlight, sometimes filtered through clouds, set red rock cliffs on fire and cast abysses into purple shadow.

Desert View overlook.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

The Grand Canyon in northern Arizona is rightfully one of the seven wonders of the world. Every year, visitors arrive at its edge and gaze down into this yawning gash in the earth. But the approach to the canyon gives no hint of what awaits. The highway passes a sweeping land of sagebrush and grass, through dwarf pinyon and juniper woodland, and into a forest of tall ponderosa pines. Then, suddenly, the earth falls away at your feet. Before you stretches an immensity that is almost incomprehensible.

Grandview Point on the South Rim.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

The canyon is negative space – it’s composed as much by what’s not there as what is. After taking time to soak in the scene, one’s eyes rove down to the bottom, where there appears to be a tiny stream. Though it looks small from this distance, 7,000ft (2,100 meters) above sea level, it is in fact the Colorado River, one of the great rivers of the West. And unbelievable though it may seem, the river is the chisel that has carved the Grand Canyon. The Colorado rushes through the canyon for 277 miles (446km), wild and undammed. Over several million years, it’s been doing what rivers do – slowly but surely eroding the canyon to its present depth of one mile (1.6km).

An awful canyon

To the east, the scalloped skyline of the Palisades of the Desert defines the canyon rim. To the north, about 10 miles (16km) as the hawk flies, is the flat-lying forested North Rim. To the west, the canyon’s cliffs and ledges, cusps, and curves extend as far as the eye can see, taking in the Havasupai Reservation and adjoining Hualapai Reservation, home to the famous Skywalk, with only distant indigo mountains breaking the horizon. Grand Canyon National Park (tel: 928-638-7888; www.nps.gov/grca; daily) is more than a million acres (400,000 hectares) of land, and this view encompasses only about a fourth of the entire canyon.

People’s reactions to their first sight of the Grand Canyon can vary widely. Some are stunned, speechless. Some are brought to tears. Still others, such as early visitor Gertrude B. Stevens, have been overcome in other ways: “I fainted when I saw this awful looking cañon,” she declared. “I never wanted a drink so bad in my life.” Regardless of your reaction, you’ll never forget your first sight.

With more than the average four-hour stay, a person can begin to explore this miraculous place, savoring different moods throughout the hours of the day, as the light constantly changes the face of the canyon.

Tip

Traffic at the South Entrance Gate often backs up during peak summer hours, but tends to be lighter at the East Entrance Gate.

The South Rim

Most visitors first see the Grand Canyon from the Grand Canyon Village at the South Rim, which is open year-round and offers the bulk of lodging, food, and attractions. Start your visit just past the South Entrance at Grand Canyon Visitor Center A [map], in a spacious pedestrian plaza that has car and coach parking and free shuttle buses (open daily 8am–5pm; plaza exhibits open 24 hours). You’ll find a large theater showing a film about the park, wall-size maps, and interpretive exhibits and books that set the canyon in a larger context and help orient visitors. Park rangers here can answer specific questions. From the plaza, it’s a short stroll, or shuttle ride, out to the level Rim Trail and Mather Point, for that virgin glimpse of the canyon and a nice place to picnic.

Tourists watch the sunset from Mather Point.

iStock

Just east of Grand Canyon Visitor Center is the bus terminal, where free shuttle buses run at frequent intervals all day along four routes: Grand Canyon Village (Blue Route), the Kaibab/Rim (Orange Route), Tusayan (Purple Route – summer only), and scenic Hermits Road (Red Route). By extending the public transportation system, and providing more park-and-ride opportunities, the Park Service aims to get people out of their cars, and get cars and development away from the rim, so as to restore that invigorating sense of discovery. Now, the ravens (and a good number of reintroduced condors, which congregate at Lookout Studio) are taking back their rightful place, soaring over the dizzying abyss and croaking their calls of greeting.

Tip

The best times to photograph the Grand Canyon are at sunrise and sunset, and on cloudy days, when shadows and contrast create the best results. Avoid the flat light of midday in the desert.

Tourists take in views from the Visitor Center Plaza at Mather Point.

Getty Images

Hermit’s Road

The historic buildings on the rim, most of them of native stone and timber, are an attraction in themselves. One is the Yavapai Point Observation Station (daily 8am–7pm), the next point west of Mather on the Rim Trail. One entire wall of this small museum and bookstore is glass, affording a stupendous view into the heart of the canyon – slices of the Colorado River, a 1928 suspension bridge, and Bright Angel Campground and Phantom Ranch B [map] tucked at the very bottom.

From here, a paved path along the rim leads to Grand Canyon Village, where shuttle buses on the Red Route head out along 8-mile (13km) Hermits Road (also called West Rim Drive). Constructed in 1912 as a scenic drive, it offers several overlooks along the way. At Trailview Point, you can look back at the village and the steep Bright Angel Trail, just west of Bright Angel Lodge, one of two main trails switchbacking down to the river. Indian Garden, a hikers’ campground shaded by cottonwoods, is visible 4.5 miles (7km) down the trail. The Bright Angel Fault has severed the otherwise continuous cliff layers that block travel in the rest of the canyon, providing a natural route for hikers into the canyon.

In the morning, mule trains plod into the canyon, bearing excited greenhorns who may wish they’d gone on foot when the day is done. The trail is also the route of a pipeline that pumps water from springs on the north side up to the South Rim. The benefit of that reliable water supply makes the Bright Angel Trail favored among canyon hikers, especially in the heat of summer. The other main trail into the canyon, the South Kaibab, has almost no shade.

Buttes and temples

Other recommended points along Hermits Road are Hopi, Mohave, and Pima. From each vista different isolated buttes and “temples” present themselves. There is the massive formation called the Battleship, best seen from Maricopa Point. There’s Isis and Osiris, Shiva and Brahma. These overblown names were bestowed by Clarence Dutton, an erudite geologist with the early US Geological Survey and protégé of Major John Wesley Powell. Dutton’s classical education inspired names with this Far East flavor. He wrote that all the canyon’s attributes, “the nobility of its architecture, its colossal buttes, its wealth of ornamentation, the splendor of its colors, and its wonderful atmosphere … combine with infinite complexity to produce a whole which at first bewilders and at length overpowers.”

At Mohave Point on a still day, you can hear the muffled roar of crashing waves in Granite and Hermit Rapids on the Colorado. With binoculars, it may be possible to spy boaters bobbing downriver in rubber rafts. The road ends at Hermits Rest C [map], an historic building with a gift shop, concession stand, and restrooms. This is also where hikers head down the Hermit Trail, one of the more accessible backcountry trails beyond the two main corridors of Bright Angel and South Kaibab. It’s about 8 miles (13km) down Hermit Canyon to a lovely streamside camp for overnight hikers.

The Santa Fe Railway built the camp as a destination for tourists who arrived on mules, while supplies were shuttled 3,000ft (900 meters) down a cable from the rim. In those days, according to author George Wharton James, the camp furnished accommodations “to meet the most fastidious demands.” The “hermit” was a Canadian prospector named Louis D. Boucher, who settled at an idyllic spot called Dripping Springs, off the Hermit Trail. Known for his flowing white beard and a white mule named Calamity Jane, Louis kept mostly to himself. He prospected a few mining claims, escorted tourists now and then, and by all accounts grew amazing fruits and vegetables down in the canyon.

Desert View Drive

Returning to the village, another road, Desert View Drive, follows the canyon rim for 25 miles (40km) to the east. Overlooks along the way display still more spectacular canyon scenery. From Yaki Point, the panorama includes the massive beveled surface of Wotans Throne, and beside it graceful, pointed Vishnu Temple. The other main hiking route, the 7-mile (11km) South Kaibab Trail, departs from near Yaki Point, snaking down the side of O’Neill Butte through a break in the Redwall Limestone, down to Bright Angel Campground and Phantom Ranch.

Tall tales

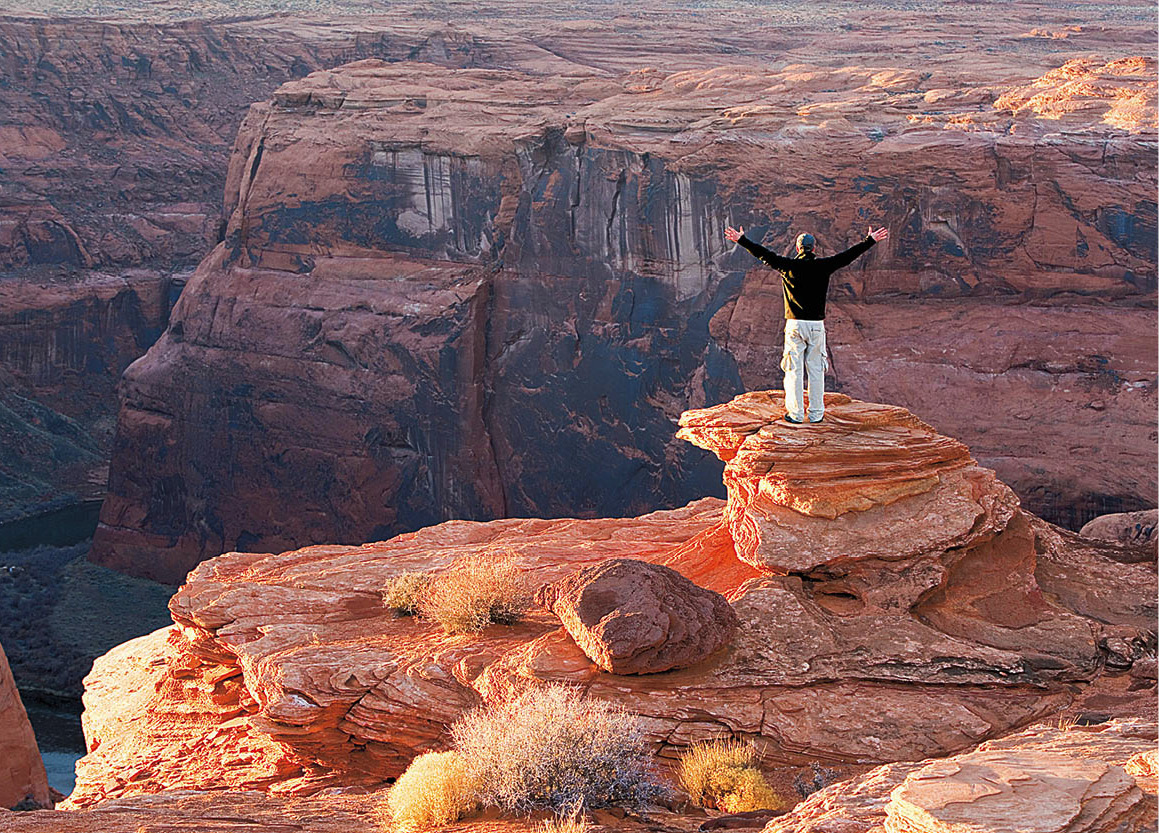

Farther east, Grandview Point looks down on Horseshoe Mesa, site of early copper mines. The Grandview Trail starts here, built by miners to reach the ore. But even a short walk will reveal that no matter how pure the ore, hauling it out was not a profitable enterprise.

Grandview was among the first destinations for early tourists to the canyon, who stayed at Pete Berry’s Grandview Hotel. One of the regulars there was old John Hance. He arrived at the canyon in the 1880s and built a cabin near Grandview. For a time, John worked an asbestos mine on the north side of the river but quickly realized that working the pockets of “dude” visitors was more lucrative. “Captain” Hance regaled rapt listeners with tales of how he dug the Grand Canyon, how he snowshoed across to the North Rim on the clouds, and other fanciful yarns.

Hiking at beautiful Havasu Falls.

iStock

His stamp remains on the canyon – there is a Hance Creek and Hance Rapid, and the Old and New Hance Trails, rugged routes that drop down into the canyon from Desert View Drive.

Sunrise illuminates the canyon rim.

iStock

In addition to great views and good stories, the drive in this area also gives a look at stands of splendid old ponderosa pines. These cinnamon-barked giants grow back from the rim, here benefiting from slightly higher elevation and increased moisture. Their long silky needles glisten in the sunlight, and a picnic beneath their boughs is a delight. Grazing mule deer and boisterous Steller’s jays may be your companions, along with busy rock squirrels looking for handouts. (Resist the temptation; feeding wildlife is strictly prohibited.) The trees growing on the very brink of the rim are Utah junipers and pinyon pines. Sculpted by the wind, they cling to the shallow, rocky soil, never attaining great heights though they can be very old. The warm, dry air rising up from the canyon explains their presence.

In certain good years, pinyon pines produce delicious, edible brown-shelled nuts. People gather them, but so do many small mammals and birds. One bird – the dusky-blue pinyon jay – shares an intimate relationship with the tree. The jays glean nuts from the sticky cones, eating some and caching others. Inevitably, some of the nuts are forgotten and grow into young pinyon pines.

Tip

Mule rides have been a tradition at the canyon for nearly a century but are not for the faint of heart. Age and weight restrictions apply. Reservations should be made several months in advance; call 888-297-2757.

The eastern tip

Just to the east of Grandview is the entrance to the Tusayan Ruin and Museum (daily 9am–5pm), which preserves the remains of masonry structures constructed some 800 years ago by Ancestral Puebloans. These early farmers were by no means the first humans to inhabit the canyon. Archaeologists have found a tantalizing stone point nearly 13,000 years old left by big-game hunters in the waning days of the Ice Age. For another several thousand years, hunter-gatherers made a living on canyon resources. About 4,000 years ago, they split willow twigs and wound them into small animal figures. They left the figures in caves in the canyon, where modern-day archaeologists have discovered them.

Lipan Point, farther east, provides one of the most expansive views of the canyon and Colorado River from anywhere along the rim. The river makes a big S-turn, with Unkar Rapid visible below. A little farther downstream is Hance Rapid, punctuating the entry of the Colorado River into the Inner Gorge.

In autumn, hundreds of hawks – Cooper’s, sharpshins, redtails, and others – migrate over Lipan Point on their way south. Nearby, in 1540, a detachment of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s Spanish entrada expedition tried but failed to reach the river. They are believed to be the first Europeans to enter the canyon proper, though Native Americans had long preceded them.

The final destination on this drive is Desert View D [map] itself. Here the canyon opens out into the wide Marble Platform and east to the huge Navajo Reservation. The Little Colorado meets the main Colorado a few miles upstream. And an interesting circular tower stands out on the edge. Mary Jane Colter, architect for the Fred Harvey Company and Santa Fe Railway, designed it. (She also designed Bright Angel Lodge, Hopi House, Lookout Studio, Hermits Rest, and Phantom Ranch.) Colter was heavily influenced by Ancestral Pueblo architecture, and Desert View Watchtower is modeled after structures she had seen in the Four Corners area. It was built in 1932 of native stone, and on the interior walls are murals painted by Hopi artist Fred Kabotie.

The North Rim

At times, especially during the summer, the concentration of people on the South Rim can get to feel a little crowded. The place to turn is the North Rim, the peaceful side of the Grand Canyon.

The scale of the canyon is invigorating.

iStock

From the South Rim, it doesn’t look very far, but the North Rim is 220 miles (346km) away by road. Leaving Desert View, join Highway 89 and head north across the Navajo Nation and part of the Painted Desert. Take Highway 89A, cross the bridge over the Colorado River at Marble Canyon, and allow time for the 5-mile (8km) detour to Lees Ferry, the put-in for Grand Canyon river trips and itself a vortex of Southwest history. This is the only place for nearly 300 miles (480km) where you can get down to the river, sit on the shore, and marvel that this is the same insignificant-looking stream you saw from the rim.

Desert View Watchtower, built in 1902 by the Fred Harvey Company, rises from the edge of the canyon.

Richard Nowitz/Apa Publications

Back on Highway 89A, drive west across the wide-open, lonesome stretch of House Rock Valley, where keen-eyed travelers may glimpse a giant California condor soaring over the Vermilion Cliffs. The road then climbs up the east flank of the Kaibab Plateau, re-entering pinyon-juniper forest and ponderosa pine. At Jacob Lake, Highway 67 winds 45 miles (72km) through the forest to the rim.

The Canyon in Winter

Winter weaves a magic spell over the Grand Canyon. In this season the rim is softened by a mantle of ermine snow, and the chilled air bristles with crystals. Pine needles are glazed with frost, and gossamer clouds snag the tops of pointed buttes. Sounds are muffled, and hectic summer days are a memory.

During the holidays, the huge rock fireplace in the lobby of El Tovar Hotel is surrounded with poinsettias. It’s tempting to spend the day indoors by the fire, sipping hot chocolate. That’s certainly an option, especially if the winds are buffeting the rim. But the outdoors beckons, and with warm clothing and the appropriate footwear you can walk along the rim path and find yourself nearly alone with the canyon.

Juncos, nuthatches, and finches flit in the tree branches. Ravens two-step out on improbable promontories, oblivious to the gaping abyss below. Tracks in the snow hint at dramatic encounters between hawk and rabbit.

Diligence is needed near the rim, though, for snow can hide a slippery drop off and trails may be icy. Ski poles, boots with instep crampons, or removable cleats can be helpful. Beware of hypothermia, too. It can strike suddenly in wet, cold, windy weather when you’re tired from exertion. Dress in layers, keep a supply of dry clothes, and drink plenty of water.

To the Kaibab Paiute Indians, who live on this side of the canyon, Kaibab means “mountain lying down.” The North Rim’s elevation does qualify as a mountain. It averages 8,000ft (2,400 meters), 1,000ft (300 meters) higher than the South Rim, making for a very different forest environment. Here grow dense stands of spiky dark spruce and fir, along with quaking aspen and big grass-filled “parks,” or meadows, where coyotes spend their days “mousing.” The limestone caprock also holds a few small sinkhole lakes. This forest supports a different variety of wildlife too – the handsome Kaibab squirrel, a tassel-eared tree squirrel of the ponderosa pines, is found only here; there’s also blue grouse; a larger population of mule deer; and a consequently larger number of mountain lions, the main predators of the deer. The North Rim is buried in snow in winter, and the entrance road is closed from the end of October through mid-May.

Because of the short season and isolation, the North Rim has never been as fully developed as the South Rim. There is a campground, small cabins, a visitor center, cafeteria, and Grand Canyon Lodge E [map], which perches on the canyon’s edge. One of the prime activities is to nab a rocking chair on the veranda of the lodge and engage in serious canyon watching.

The road to transcendence

From the lodge, a short trail goes to Bright Angel Point. Though you’re still looking at the same canyon, the north side’s greater depth and intricacy are immediately apparent. This is due partly to the Grand Canyon’s asymmetry: the Colorado River did not cut directly through the middle of the Kaibab Plateau but slightly off-center to the south. Also because of its greater height and southward tilt, more water flows into the canyon here than away from it as on the South Rim. Thus the northern side canyons are longer and more highly eroded. The North Kaibab Trail along Bright Angel Creek, for example, is 14 miles (23km) long, twice the distance of the corresponding trail on the south side.

While many people take the North Kaibab, the only maintained trail into the canyon, all the way down to the river for overnight stays, this trail also lends itself to wonderful day hikes. Even a short hike to Coconino Overlook (1.5 miles/2.4km round-trip) or Supai Tunnel (4 miles/6.5km round-trip) reveals the canyon’s natural beauty and size. Ambitious day hikers may want to continue to Roaring Springs (9.5 miles/15km round-trip). The hike there and back is extremely strenuous and takes 7−8 hours (be sure to start by 7am). Roaring Springs lies 3,050ft (930 metres) below the canyon rim. Do not attempt to hike all the way to the river in one day. Other shorter walks on the rim include the Transept, Widforss, and Ken Patrick trails, which combine forest and canyon scenery.

The view from the North Rim.

iStock

A drive out to Point Imperial F [map] and Cape Royal G [map], on the only other paved road, is well worth the time. At 8,800ft (2,700 meters), Point Imperial is the highest prominence on either rim of the canyon. Its eastward-facing view showcases Mount Hayden, Kwagunt Butte, and Nankoweap Mesa in the Marble Canyon portion of Grand Canyon.

From there, the road goes out to Cape Royal, where it ends. Clarence Dutton also named this promontory; his description of sunset there strains even his exuberant prose: “What was grand before has become majestic, the majestic becomes sublime, and ever expanding and developing, the sublime passes beyond the reach of our faculties and becomes transcendent.”

Go vertical

With the first step down into the Grand Canyon, the horizontal world of the rims turns decidedly vertical. A walk down a trail, even for a short distance, is the only way to begin to appreciate the canyon’s great antiquity and sheer magnitude.

The view from the patio of Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park.

Grand Canyon Lodge

A word to the wise, though. Adequate preparation for this backcountry experience is essential. A Grand Canyon trek is the reverse of hiking in mountains: the descent comes first, followed by the ascent, when muscles are tired and blisters are starting to burn. And no matter what trail you follow, the climb out is always a long haul against gravity – putting one foot in front of the other and setting mind against matter. Never try to hike to the river and back in one day. For first-time hikers, the maintained corridor trails are recommended: the Bright Angel, or the South or North Kaibab. Also note that all overnight hikes require permits, available from the Backcountry Information Center (tel: 928-638-7875; www.nps.gov/grca) in Grand Canyon Village; day hikes do not.

Tip

Want to learn more? The Grand Canyon Field Institute (tel: 928-638-2485) offers 1- to 10-day trips covering a wide range of topics, including geology, ecology, photography, and cultural history.

There are two other critical considerations – heat and water. As you descend into the canyon, you pass from a high-elevation, forested environment into desert. Temperatures in the inner canyon are routinely 20 degrees warmer than the rim – from June to September that means upwards of 110–120°F (43–49°C) down below. That kind of unrelenting, energy-sapping heat, coupled with a shortage of water, can spell disaster for the unprepared. In summer, each person should carry – and drink – a minimum of a gallon (4 liters) of water apiece. Along with water, a hiker should eat plenty of nutritious, high-energy foods to avoid hyponatremia (low sodium levels caused by overconsumption of water and not enough food) and take frequent rest stops. A hat, sunscreen, and sunglasses are necessary items. To avoid the extreme heat, hike in early morning and early evening. Or avoid summer altogether and go in spring or fall, which are the best times for an extended canyon hike.

The Inner Canyon

Dropping below the rims into the canyon’s profound silence, you enter the world of geologic time. Recorded in the colorful rock layers is a succession of oceans, deserts, rivers, and mountains, along with hordes of ancient life forms that have come and gone. The caprock of the rims, the Kaibab Limestone, is 250 million years old. It is the youngest layer of rock in the Grand Canyon; every layer beneath it is progressively older, down to the deepest, darkest inner sanctum of black schist that rings in at close to 2 billion years.

Tip

Short helicopter tours are available at Grand Canyon Airport in Tusayan, flying 1,000ft (300 metres) above the canyon for spectacular views.

As you put your nose up against the outcrop, you’ll notice that this creamy-white limestone is chockablock with sponges, shells, and other marine fossils that reveal its origin in a warm, shallow sea. The next obvious thick layer is the Coconino Sandstone. Its sweeping crossbeds document the direction of the wind across what were once dunes as extensive as those in today’s Sahara Desert. It isn’t hard to imagine, because already, even in this first mile of the trail, the canyon begins to look and smell like the desert – dusty and sun-drenched. Beneath the Coconino is the Hermit Shale, soft, red mudstone that formed in a lagoon environment. Underlying the Hermit is the massive Supai Formation, 600ft (180 meters) thick in places, the compressed remains of mucky swamp bottom 300 million years past. The Redwall Limestone is always a milestone on a Grand Canyon hike, passable only where a break has eroded in the 500ft (150-meter) -high cliffs. Beneath the Redwall are the Muav Limestone, Bright Angel Shale, and Tapeats Sandstone – a suite of strata that indicate the presence of, respectively, yet another ocean, its nearshore, and its beach. Throughout most of the canyon, the tan Tapeats reclines atop the shining iron-black Vishnu Schist, the basement of the Grand Canyon and arguably its most provocative rock.

At the bottom, embraced in the walls of schist, are the tumbling, swirling waters of the Colorado River, the maker of this, its greatest canyon. The river, aided by slurries of rock and water sluicing down tributary canyons, has taken only a few million years to gnaw down into the plateau to expose almost 2 billion years of earth history.

The Colorado River flows between the sheer limestone walls of the Inner Canyon.

iStock

Soak hot feet in the cool water. Listen to boulders grinding into gravel on their way to the sea. Consider these old rocks in this young canyon. Ponder our ephemeral existence in the face of deep time.

Havasu Canyon

Havasu H [map], a side canyon in the western Grand Canyon, has been called a “gorge within a gorge.” Within it flow the waters of Havasu Creek, lined with emerald cottonwood trees and grapevines and punctuated by travertine falls and deep turquoise pools, paradise in the midst of the sere desert of the Grand Canyon. A visit is an unforgettable experience, a gentle introduction to the Grand Canyon and to the Havasupai Indians, the “people of the blue-green water,” who have made their home here for at least seven centuries.

Getting there is no easy matter. The journey requires a 62-mile (100km) drive north of Route 66 (about 190 miles/300km from the South Rim) to a remote trailhead, then an 8-mile (13km) hike or horseback ride to the small village of Supai on the canyon bottom. In past times, the Havasupai partook of what the land offered. Evidence is seen along the trail in large rock piles, the pits used year after year for roasting the sweet stalks of agave. In their rocky homeland are distinctive natural features that hold great significance for the Havasupai. Rising high above the village is a pair of sandstone pillars known as Wigleeva. To the Havasupai, these are their guardian spirits; as long as they are standing, the people are safe.

Note that Supai is subject to severe flashflooding. In 2008, a major flashflood, compounded by the collapse of a dam, caused widespread damage and required the evacuation of residents and tourists by helicopter. The canyon reopened to visitors in 2011, but facilities are currently limited to a trading post, post office, school, tourist lodge, and tribal museum. Mail and supplies arrive by mule or horse, helicopter, and internet. For more information on visiting, contact the Havasupai Tourist Office (tel: 928-448-2127).

Waterfalls

About 1.5 miles (2.5km) beyond the village is the first of the famous waterfalls – Navajo Falls. A short distance beyond is 100ft (30-meter) -high Havasu Falls and the campground. The trail continues on to Mooney Falls, known as the Mother of the Waters to the Havasupai. To go farther down canyon requires a steep descent next to the falls on a water-slickened cliff face, with the aid of a chain railing. It’s another 3 miles (5km) to Beaver Falls, a popular day hike for boaters coming up from the river to frolic in the beautiful pools. Those who make the journey know why Havasu is often called the Shangri-la of the Grand Canyon.

Return of the Railroad

Locomotives began beating a path to the Grand Canyon early in the 20th century. It was the end of the trail for the old stagecoach.

In 1883, cowman William Wallace Bass was out chasing doggies south of the Grand Canyon, when he found himself on the brink of the chasm “scared to death.” Two years later, he set up cabins on the rim at Havasupai Point, where tourists came to see the great sight. From the small town of Williams, they boarded stagecoaches and bounced along the 72 miles (116km) to the camp, where Bass escorted them into his “dear old Canyon home.”

His competition in those days was Pete Berry’s Grandview Hotel out at Grandview Point. There, tourists arrived after an 11-hour trip from Flagstaff aboard the Grand Canyon Stage and stayed at Berry’s hotel or at John Hance’s cabins nearby.

But things changed. On September 18, 1901, the Grand Canyon Railway’s Locomotive 282 pulled up to the budding Grand Canyon Village on the South Rim. Passengers found the three-hour train ride from Williams far preferable to the dusty daylong stage trips. The arrival of the railway spelled the end of Bass’s and Berry’s tourist headquarters. With construction of the Bright Angel Lodge and Fred Harvey’s five-star El Tovar Hotel, Grand Canyon Village became (and has remained) the center for visitors to the South Rim. El Tovar’s patrons were treated to fresh meals, prepared and served by Harvey girls dressed in white starched aprons. Accommodations were luxurious, and rocking chairs on the spacious porch permitted a classic canyon view with little exertion.

Despite the Harvey Company’s dominance on the rim, other entrepreneurs came on the scene. Ralph and Niles Cameron staked mining claims and ran the Bright Angel Trail as a toll route for a time. In 1904, brothers Emory and Ellsworth Kolb built their photographic studio at the trailhead. They took pictures of people departing on mule trips in the morning, ran 4 miles (6km) down to a water source at Indian Garden to develop the film, and were ready with prints when the tourists returned. In 1911, the Kolb brothers made a film of their wild trip down the Colorado River, which visitors watched in their studio for 65 years.

Again things changed as Americans embraced the automobile, ending the era of rail service to the Grand Canyon in 1968. But another entrepreneur stepped in, restored the tracks, cars and locomotives, and relaunched the Grand Canyon Railway in 1989. Once again, locomotives chug out of the Williams station each morning, making the 135-minute, 65-mile (105km) run to the canyon. Passengers have a choice of restored coaches or the more opulent club or parlor cars. The three-hour canyon layover allows plenty of time for lunch, a bus tour, or a stroll along the rim.

Spending a night in the canyon is also an option. It’s a relaxing ride back, complete with crooning cowboy troubadours and mean hombres who stage a hilarious mock holdup.

Contact the Grand Canyon Railway at 800-843-8724 or www.thetrain.com.