Even though Nica was a member of the first generation of emancipated British women, well-brought-up young ladies were still expected to behave like the weaker, gentler sex. Submissiveness, modesty and humility were required female attributes. English society was so small and introspective that everyone knew everyone else’s business. If events were not already listed in The Times or transmitted over the servants’ network, gossip whistled round the hunting fields and drawing rooms. Nica’s reputation as a wild child was broadcast before she even stepped onto the dance floor. My father’s mother Barbara, who used to stay at Tring Park, wrote in her private diaries in 1929: “Amazing red house with plate glass windows. Indoors yellow furniture in the bedrooms, blue bows on my bed and very few bathrooms. Wonderful Lady Rothschild with a lovely witchy face and Uncle Wally with spaghetti in his beard and the old housedog way of being treated. Little sister Nica full of fat and high spirits.”

In 1929, at sixteen, Nica exploded out of the nursery. Finally allowed to stay up after nine o’clock, Nica decided that sleep was a waste of time and switched her preferred waking hours from day to nighttime. The Tring Park visitors’ book shows that the house was now packed with people on most weekends. Selected guests were asked to attend secret late-night sessions in the attic. Between the hours of 2 and 5 a.m., after the stuffier adults had gone to bed and before the servants awoke, the young Rothschilds entertained their friends with bottles of family wine and jazz records. “We used to call it corridor creeping,” my grandmother explained with a wicked giggle.

Great-aunt Miriam at work (Photographic Credit 8.1)

Rozsika had no idea how to manage her wayward daughter. Cut off from her native Hungary and its traditions, she could hardly rely on guidance from her ageing mother-in-law or the eccentric Walter. Adrift in a sea of arcane and fairly incomprehensible rules, Rozsika sought the counsel of society ladies. The first piece of advice both given and taken was to send Nica to a finishing school in Paris. While ostensibly a reputable establishment, it was in reality “operated by wig-wearing lesbian sisters,” Nica told the critic and writer Nat Hentoff in a profile for Esquire magazine in 1960. These redoubtable women, she said, “made passes at the girls. They taught us how to put on lipstick and gave us a little literature and philosophy to go with it and if you weren’t a favourite, woe betide you. They used to charge the earth for corrupting all those girls. It was all quite revealing.”

Graduating from this lesbian seminary in the summer of 1930, Nica joined her sister Liberty on a grand tour of Europe. A governess, a chauffeur and a maid accompanied the young ladies. The network of maternal and paternal cousins meant that the sisters were in constant social demand. In France, they stayed at the magnificent Château Ferrière. In Austria, Nica waltzed at balls and rode Lipizzaner horses at the Spanish Riding School. In Vienna, she got involved in her first international scandal, although admittedly it was not, for once, of her making. An impoverished, opportunistic countess, hoping to restore her family’s fortunes, announced that her son and Miss Pannonica Rothschild were engaged. There was little substance to the romance apart from a shared love of riding. It was the countess’s bad luck that Rozsika, who took every foreign newspaper, spotted the announcement and immediately published a robust disclaimer.

In Munich, the two sisters took a painting course. “It was during Hitler’s rise, but we weren’t aware of what was going on until it finally occurred to us that the people who were behaving boorishly were those who knew we were Jewish,” Nica told Esquire. It was a rare moment of political awareness; the sisters were strangely oblivious to international events. Another major incident that appeared to pass them by was the Wall Street crash of 1929, although the collapse of the stock market and the ensuing depression bit deeply into the family’s fortune.

With an unearned income at their disposal but no guiding Rothschild male role model, Nica and her siblings made up their own rules. The four children of Charles and Rozsika were driven by a sense of entitlement rather than duty. Miriam, Victor and Nica masked their insecurities with an air of utter imperiousness. None of them was popular or even well liked.

Despite her best efforts, the finishing schools and London party circuits, Rozsika was failing to marry off her daughters. Liberty, though greatly admired by her French Rothschild cousin Alain, was too nervous to cope with affairs of the heart. Miriam was more interested in looking down a microscope than into the eyes of young men. In 1926, aged eighteen, she decided not to waste nights dancing and flirting, and enrolled secretly in evening classes at Chelsea Polytechnic. Having gained the most basic qualifications, she got a paid job, studying marine biology in Naples. Her family was baffled, while 1920s polite society was shocked. Why would anyone in her position choose a job over a comfortable life? Possessed by a determination to complete the research started by her father, Miriam became one of Britain’s leading naturalists, and a world expert in fleas, butterflies and chemical communications. Without the proper credentials to win a place as an undergraduate, she went on to be awarded eight honorary doctorates, among them from Oxford University in 1968 and Cambridge in 1999, as well as a Fellowship of the Royal Society in 1985, and she was later made a Dame of the British Empire.

Thus Miriam showed a generation of young women, including Nica, that there were alternative ways of living and that passions could transmute into careers. By the time Nica left the nursery, Miriam was well advanced in her studies. Following her apprenticeship in Naples, she spent the inter-war years developing a chicken feed made from seaweed rather than grain. However, the inspiration for her work still came from her father’s unfinished research into butterflies and fleas. Miriam became the dutiful eldest daughter who stayed at home, worked assiduously and kept alight the flame of her parents’ memory.

Without Miriam’s involvement, encouragement and memories, this book could not have been written, yet her achievements and her forceful character also threatened to derail the project. Miriam was so strong and her recollections so vivid that her voice at moments seemed to overpower Nica’s. Sometimes when I asked Miriam about Nica, she would talk instead about herself or Liberty. I would question other people about Nica and they would only want to talk about Miriam. Why aren’t you writing about her? they would say. She was the really distinguished, high-achieving one.

I wondered whether Nica resented living in the shadow of her highly successful sister and brother. Was her later decision to live abroad an attempt to establish herself elsewhere, away from their spotlight? A by-product of coming from a highly successful family, as I know, is being treated as someone’s daughter, sister, cousin, niece or mother rather than a person in one’s own right. I stuck up for Nica and for this project. Perhaps Nica achieved something that cannot be measured in honorary degrees and paper qualifications, I would remonstrate, something less public but nonetheless valid. Minor characters, I argued, are still important.

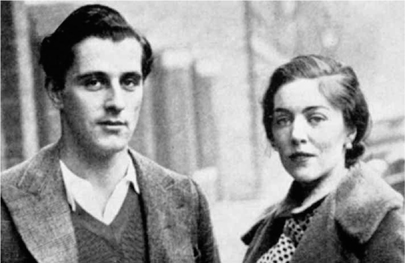

Victor and his first wife, Barbara (née Hutchinson) (Photographic Credit 8.2)

As the youngest child, Nica never felt obliged to continue any tradition, so she did what pleased her, when it pleased her. Liberty, however, could never make the most of her huge potential, and would remain incapacitated by psychological fragility for the rest of her life.

Victor had no intention of letting a career in banking get in the way of his real passions. From an early age, as the longed-for son and heir, he had been over-indulged and brought up to believe that his will was omnipotent. When as a tiny child he found fire amusing, his mother instructed a servant to walk backwards in front of his pram, lighting matches. At school when he was bored by lessons he was allowed to skip classes to concentrate on cricket. He went on to play at county level for Northamptonshire. Miriam became his manager and, in the absence of a father or an interested mother, she attended all his matches.

At Cambridge, Victor read Natural Sciences, hardly a surprising choice for a boy whose first memory was being asked by his father to catch a gynandromorph Orange-tip. At university, a whole world opened up to him; Victor realised his intellectual potential and found his peer group. Though he was known at university for being a playboy who drove an open-top Bugatti and collected rare first editions, for the rest of his life Victor valued academic prowess over possessions. The people he really admired were scientists, dons, thinkers and intellectuals. His forebears had used assets and wealth to create a sense of identity; Victor relied on being clever and being surrounded by clever people. His other great passion was jazz and he considered becoming a professional musician. Hearing that the great jazz pianist Teddy Wilson was giving lessons in London, Victor signed up and took his little sister Nica to watch. Years later Teddy Wilson was Nica’s entrée to the New York club scene.

Victor’s first group of university friends included two young men, Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt, who persuaded him to join their discussion group, the Apostles. Victor saw them as allies who shared a love of literature and learning, and a hatred of fascism. In the period from 1927 to 1937, twenty out of twenty-six of the group’s new members were socialists, Marxists, Marxist sympathisers or communists. For a young Jew watching the rise of Nazism in Germany, becoming a left-wing sympathiser was not unexpected.

Graduating from Cambridge, Victor was awarded a triple first and was elected a Fellow of Trinity. During the war he worked at MI6 and was awarded a George Medal for bomb disposal, claiming that years of copying Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum’s chords was an ideal preparation for such a tricky task.

Yet for all this loyal service, when it emerged after the war that his two great friends Burgess and Blunt were Soviet spies and that two other members of the Apostles were also double agents, the finger of suspicion came to hover over Victor and would continue to do so for most of his life. One book claimed that he was the “Fifth Man” and although this turned out to be John Cairncross, innuendoes still haunted Victor. On December 3, 1986, he took the unusual step of publishing a letter in the British press stating, “I am not, and have never been, a Soviet agent.” Even when he was cleared by Mrs. Thatcher, the whispers went on. Later he told his biographer Kenneth Rose that discovering Blunt was a double agent had been “devastating and crushing beyond belief.”

Nica, the debutante, presented at court in 1932 (Photographic Credit 8.3)

Victor continued to work in the field of science and, in particular, on the reproductive system of sea urchins. Later he and Miriam became the only brother and sister to have both been made Fellows of the Royal Society. As Miriam put it, “Of course my brother got into the Royal Society long before I did. Chiefly, I think, it was due to prejudice against women. Except for the fact that I hadn’t been to a public school like my brother—I was educated, or uneducated, at home—I think I was always a rather better zoologist than he was.”

Despite their apparent differences, Victor always looked after his little sister Nica, and they shared a love for music and socialising. Nica was extremely pretty, not at all serious like her two sisters, and Victor liked to show her off. It was Victor who introduced her to the latest movements in modern jazz and encouraged her to learn to fly. A great lover of fast cars, Victor taught Nica to drive and bought her a racy sports car for her eighteenth birthday. Even when he became exasperated by her chosen lifestyle, Victor continued to take care of her, indulging her with random acts of kindness, although my father Jacob attests to the fact that Victor found it hard to show similar affection or generosity to any of his six children.

Nica was expected to marry a Jew but eligible suitors were in short supply. Having put her through finishing school and sent her on a grand European tour, Rozsika next decided to launch her daughter in society.

This annual British tradition, known as the Season, was open to well-connected young women and men. Following a custom that endured until 1958, Nica wore white and curtsied to a huge white cake at Queen Charlotte’s Ball. For the next three months she took part in a merry race known to some as the marriage market. Given that only a handful of Jews attended, it was unlikely that Nica would meet any “Mr. Rights” among the hundreds of young debutantes and “debs’ delights” being presented to the King and Queen.

In June 1932, Nica was formally presented to King George V and Queen Mary and thrown into a swirl of debutante balls and coming-out parties. “I burst forth on an astonished world and did my curtsies without falling down,” she told Nat Hentoff. Having already put two elder daughters through the Season, Rozsika could not face chaperoning Nica to a third. The task of seeing the young Miss Rothschild home to bed fell instead to Grandmother Emma’s hapless chauffeur. Her cousin Rosemary remembers that Nica rarely came home at the appointed time.

The family lived in Kensington Palace Gardens, a gated road. While it was easy to give the chauffeur the slip, it was much harder to climb over high railings in the dark, wearing a floor-length ball gown. There were approximately four balls a week while the Houses of Parliament were in session between November and May. Wanting to get a flavour of what it was like, I interviewed Nica’s near contemporary, Debo, the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire (née Mitford). Like the Rothschilds, the Mitford girls were rather eccentric. Unity used to bring a pet rat to dances and Diana expounded her radical political views to her partners during the foxtrot. Debo explained that girls took the whole thing in their stride. “It was rather like going to the office,” she said. “It’s just what one did but it was such fun.”

It is easy to trace Nica’s progress through the London Season. Every dance was listed in The Times, often accompanied by a detailed description of what the debutante was wearing and which designer had made her dress. Daywear was prescriptive; there were many designers but few variations. In the year of Nica’s coming-out it was de rigueur to wear short fur cuffs that could be slipped off and turned into muffs. Dresses were often floral and trimmed with silk motifs. Skirts were to the knee and made from soft tweed or crêpe, occasionally adorned with velvet belts of two colours twisted and tied in sharp knots. Nica’s clothes were made in Paris by leading couturiers Worth and Chanel. The Rothschild jewels, including emeralds the size of pigeons’ eggs and strings of the finest white diamonds, belonged to Victor but were loaned out to his wife or sisters for special occasions.

Rozsika announced in The Times Court Circular that her daughter’s coming-out ball would be held on June 22, 1932, at 148 Piccadilly, her mother-in-law Emma’s house. My father’s mother Barbara, who was being courted by Victor at the time, described the evening in her personal diary:

At dinner there were three tables, the big middle one for all the old people—headed by the matriarch looking superb and matriarchal—the younger matriarch [Rozsika] next to Winston [Churchill]—the other table headed by the future matriarch Miriam and lastly Victor’s table for Nica. The dance after was quite marvelous [sic], the great rooms with gilt and chandeliers, plush gold chairs and huge looking glasses, masses of champagne and people streaming up the stairs from the hall in all their jewels and grandest dresses. The park was open behind the house. Nica was pure prewar perfection. Some of us went to the Café de Madrid. Nica was chased in Piccadilly and rescued by Victor.*

My father’s sister Miranda was one of the few Rothschilds who often visited her aunt Nica in New York. She understood the nuances of English Rothschild life, as well as being sympathetic to what Nica was seeking in New York. “The problem with putting all that ‘society stuff’ in your book,” said Miranda during a recent conversation, “is that it makes Nica and Victor sound conventional. They were completely, totally eccentric. They were not like anyone else. My father [Victor] used to water-ski in a Schiaparelli silk dressing gown and he stripped naked whenever, wherever, he felt like it. Nica and her siblings only went to parties because it pleased their mother.”

The children were not, Miranda told me, remotely interested in being accepted in high society. Victor was a “crashing intellectual snob,” Nica something of a musical snob; but neither ever took the slightest notice of a person’s social standing or background. What was really important to them? I asked. “Music!” she replied. “Victor and Nica were mad about music. Victor, who was a gifted pianist, toyed with a career as a jazz musician.” For Nica, the Season was nirvana, but not because of the young men: what she really loved was the music and musicians.

Nica’s first love was the American bandleader Jack Harris. In film footage of Harris shot at the Café de Paris, London, in 1934, he shimmies across the dance floor, violin in hand. Swinging slightly from foot to foot, Harris sometimes draws a bow across his fiddle or sings a little, but more often than not he is caught returning the appreciative glances of fawning debutantes. Although fifty-five years had passed since their last meeting, Nica told me that she could remember every detail including his phone number, his favourite drink—brandy—and that he liked his eggs sunny side up. Whether or not he took her virginity is unclear, but Nica seized every opportunity to see him. I asked Debo Devonshire whether she was shocked by Nica’s infatuation. “Shocked! Of course not. Everyone was in love with the bandleader. They were by far the most attractive men in the room. My particular favourite was a man called Snakehips Johnson. He was killed in the war. A tragedy.”

Big bands visited regularly from America. Some played at the debutantes’ balls, others at London venues. Victor took his little sister to Streatham Town Hall to see Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman. Since the première of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring in 1913, the year of Nica’s birth, music had changed beyond all recognition. It was no longer something to be appreciated when perched on a gilt chair, or the accompaniment to executing perfectly co-ordinated steps: music had exploded out of the cradle of convention. It poured from radio sets and roared around the dance floors. The emancipation of music freed the younger generation. Finally they had something that their parents despised and couldn’t understand that was exclusively, gloriously theirs.

The Café de Paris, London’s most fashionable party venue during the 1930s, where Nica met her first love, bandleader Jack Harris (Photographic Credit 8.4)

In Europe and America, musicians responded to social and political change by throwing out the long-established rule books of how pieces should be constructed. On the dance floors none of the young cared for an allegro or a scherzo; they wanted rhythm, something they could dance and sing to, something that reflected new-found opportunities and freedom. It was called swing. On opposite sides of the Atlantic, separated by a vast ocean, Nica and a young African-American high-school drop-out by the name of Thelonious Monk were listening to the same music, at the same time. Their backgrounds were disparate, their circumstances could not have been more different, but the soundtrack to their lives was exactly the same.

* Unfortunately no further details exist.