After Nica moved to the Bolivar Hotel, she and Monk chose a magnificent Steinway piano for her new suite. “That’s where he wrote ‘Brilliant Corners,’ ‘Bolivar Blues’ and ‘Pannonica.’ And he would be up there all day long,” she reminisced.

The album Brilliant Corners was Monk’s musical tribute to his new friend and contained the song “Pannonica.” Only a few women received the honour of a special Monk dedication: “Ruby My Dear” was dedicated to his first love, Ruby Richardson; “Crepuscule with Nellie” was a love song composed for his wife; “Booboo” was written for his daughter Barbara.

It was the first time Nica had been involved in the creation of an album, witnessing every stage from its composition to the final recording. An obsessive documentarian, she took photographs of Monk at work and recorded the practice sessions on her portable tape recorder. One of her snapshots shows Monk, Sonny Rollins and Al Timothy* rehearsing “Brilliant Corners.” The sense of excitement is palpable. Monk, a cigarette hanging from his mouth, stands in the centre, staring intently at the keys and flanked by his friends. All three are united in the pursuit of a song, by their attempt to capture a musical dream. The composer David Amram was also there but out of shot. “That was one of the most amazing things I ever heard in my life. They just kept going back and forth, stopping and starting, until they finally got to the end of the tune. Of course Monk knew it already but he was teaching Sonny.”

Monk and Nica, Central Park, 1956 (Photographic Credit 19.1)

Monk insisted that the musicians learn the notes by heart. The music was composed in an unusual thirty- rather than thirty-two-bar structure but, when they finally got to the studio, Monk again changed the tempo and rhythm. The producer Orrin Keepnews told me it was a minor miracle that the recording was finished at all. Sonny Rollins kept pace but Oscar Pettiford and Max Roach kept threatening to walk out.

Nica played a vital role, financing some of the rehearsal sessions and even rounding up the musicians. “It was Nica who called me up,” Sonny Rollins said, “Nica who came and got me there.” At the time Nica was registered as a manager and licensed by the American Federation of Musicians. Her clients included Horace Silver, Hank Mobley, Sir Charles Thompson and the Jazz Messengers. “To me,” Nica said, “a manager should be the errand boy of the musicians. He should do the dirty work. A musician should never have to sit around a booking agent’s office and try to sell himself.”

Meanwhile, an ocean away, Miriam was staring down her microscope, or noting the activities of fleas and butterflies. Both sisters had found a fulfilling, engrossing obsession and a world where they could make a difference. Miriam, I suspect, would scoff at any parallels between her and Nica. For Miriam, nothing came close to the miracle of scientific exploration, the thrill of understanding and seeing connections in the natural world. She fought hard to get the academic training required to be a pioneer in her field. She also had to overcome prejudices. Some people assumed, because she was a Rothschild, that she could not be serious about work, that she did not need the money, so why should she bother? Others assumed that she could not combine research and motherhood. Only time, dedication and dogged hard work silenced her critics.

Unlike her sister, Nica approached her special subject without discipline or analysis but with equal amounts of passion and enthusiasm. For Nica, understanding the jazz family tree—the myriad relationships and influences handed on like batons between generations of musicians, across oceans and races—was every bit as fascinating as the life cycle of a flea. Both sisters made it their life’s work to preserve and publish their findings. Both sisters were seeking the same outcome but in different milieus.

Nica’s stay at the Bolivar was short-lived, as the other guests hated the all-night jamming sessions. Nica could not understand their antipathy. “People complained about the noise, not realising that they were hearing this fantastic music they would never hear again in their lives and I was thrown out of there,” she said, laughing on tape at the memory.

Her next home was a small hotel famous for its literary salon, the Round Table, started by Dorothy Parker and her friends. “I went to the Algonquin, because they were supposed to be broader-minded and they liked having geniuses there,” Nica recalled. “But Thelonious turned out to be one genius too far for them.” At the time Nica had arranged for Nellie to have treatment in a private nursing home in Westchester. The Monk children, Toot and Barbara, stayed with relations while Monk moved between the family apartment and Nica’s suite at the Algonquin.

Thelonious started walking around the corridors on other floors of the hotel, and he would be wearing a red shirt and shades and carrying a white walking stick in his hands, and he would push open the door [of someone’s room] and stick his head in … and say, “Nellie?” All these old ladies who had been living at the Algonquin for about fifty years got the wind up … and they started sending for their trunks from the attic. Saying they were cutting out.

Nica laughed while describing her friend’s escapades.

I got this very polite call from the manager, saying, gee, sorry, Baroness, but Mr. Monk is no longer welcome at the Algonquin. So, well, actually we got around that for a short while by sneaking in when the night manager’s back was turned and walking up one flight of stairs and ringing for the elevator from there. But one day the night manager was in the elevator and he came up [with us], so we had to stop that, so I obviously wasn’t going to stay there if Thelonious wasn’t allowed.

It was increasingly clear that Monk could not be left alone. Behavioural traits once excused as “eccentricities” were becoming more pronounced. What was harder to unpick was if his behaviour was the result of mental instability or drug abuse. When his mother Barbara lay ravaged by cancer in St. Clare’s Hospital, Thelonious refused for a long time to see her, reasoning that it would upset him more than it would comfort her. When she died on December 14, 1955, Monk was holed up in a shooting alley with some addict friends and missed the funeral completely. He just made it to the end of the wake that followed.

His equilibrium was further rocked when the family’s apartment caught fire and, although no one was hurt, their possessions—including clothes, books, furniture and Monk’s music manuscripts, plus his upright piano—were all destroyed. The loss of his music was so devastating to him that Monk never again went anywhere without it.

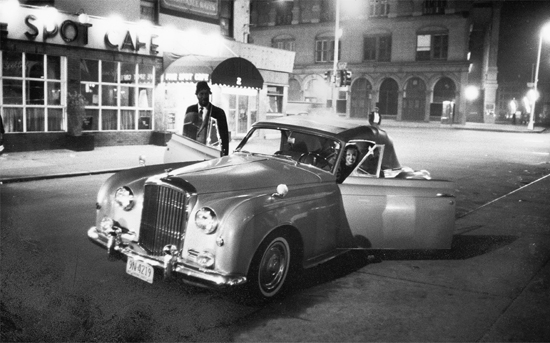

To make getting around town easier for him, Nica bought Monk a black-and-white Buick. His first (and last) car, he spent hours aimlessly driving it around the city. Nica switched her own car from a Rolls-Royce to a silver S1 Continental Convertible that became known as the Bebop Bentley.

In early 1956, Monk played a well-received concert at the Town Hall, one of the few venues where he could perform without a cabaret card. His album Brilliant Corners was released to good reviews. He engaged an eager if inexperienced manager, Harry Colomby, a schoolteacher who had no experience in the music business but was a passionate supporter of Monk as well as an honourable man. Unmotivated by financial rewards, Colomby wisely did not resign from his day job and his endeavours on behalf of his eccentric client bordered, at times, on the heroic.

In spite of Nica’s and Colomby’s efforts, Monk still failed to get back his licence, so he spent his days composing and hanging out. Finally, the family apartment had been renovated, and the Monks were able to move back into it. To celebrate, Nica rented her friend a Steinway baby grand, an instrument that must have eaten up most of the small living space.

Shortly after Christmas 1956, Monk had his first serious breakdown. Driving through Manhattan in the Buick, he hit a patch of ice and skidded into another car. He got out and stood silently in the middle of the road. The other driver called the police, who left a note on the car: “Psycho taken to Bellevue.”

Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital was heavily guarded and surrounded by a high fence. It often had more patients than beds but for its inmates it was easier to get checked in than checked out again. It took the combined efforts of Nellie, Nica, Dr. Freymann and Harry Colomby, plus affidavits from leading producers, to persuade Bellevue to let him go.

Shortly after Monk’s release (without a diagnosis), Nellie collapsed again. This time she needed an operation to remove her thyroid. Monk coped with her absence by working tirelessly on a song, “Crepuscule with Nellie,” a title suggested by Nica.

Victor Rothschild, exasperated by calls from his sister and legal summonses from hotel managers, instructed his agents to find Nica a house. In 1958, they identified the perfect property. It belonged to Josef von Sternberg, Marlene Dietrich’s director, who was moving to California.

Kingswood Road is an ordinary suburban street in Weehawken, New Jersey, but number 63 has one of the most stunning urban views in the United States. Poised on a hill, the house looks across the Hudson River to the skyline of Manhattan’s West Side and out towards the George Washington Bridge to the north. It is a dramatic sight at any time of day. In the early morning, the sun rises over the back of Wall Street, light catches the great plumed smokestacks and rays glint off the silver water towers crowning every downtown block. In the early dusk—the magic hour, as painters call it—the setting sun bathes the windows in a golden hue and turns the river blood red. After the sun has gone down, the vista changes to an icy blue and when darkness falls at once the whole sky shimmers with myriad different lights. The huge apartment blocks give off an opalescent glow and office windows twinkle like tiny stars. Car lights shoot up the West-side Highway, like red-and-white streaks, while flashing neon signs battle with each other to seduce and entrap passing customers.

Compared to the Rothschild properties she had known since birth, Nica’s new house was a modest affair: three boxy rooms stacked one on top of the other. Almost the biggest was the garage; a galley kitchen led directly off that and beyond it a large sitting room with a huge plate-glass window overlooked Manhattan. Upstairs there was another large bedroom, Nica’s, and at the back a smaller room. When her children came to stay, the Bentley was parked in the street and the garage became a bunkroom.

Kingswood Road, Weehawken, New Jersey, was Nica’s last home, from 1958 to 1988. (Photographic Credit 19.2)

Nica’s view over the Hudson River (Photographic Credit 19.3)

Unlike her forebears, Nica was not interested in possessions or amassing great collections. She loved live music, an art form that evaporates the moment it comes into existence. She owned many records and had captured hundreds of hours of bootleg recordings, but it was clear that it was the performance that mattered to her and it was, above all, about being there, not about owning it.

Her house was modest and contained nothing of great value. Instead of Rubenses, Reynoldses, Van Dycks, Guardis and Bouchers hanging on her walls, Nica had randomly stuck album covers; instead of back stairs so that servants could pass unnoticed, there were flaps and walkways for her pet cats. The curtains were tatty and the furniture, apart from the grand Steinway piano, was strictly functional. The only real hints of her European past—the enormous fortune and different way of life—were her title, the monogrammed notepaper, the Bentley, the fur coat and the strings of perfect pearls.

Nica’s guests were unlikely to be offered food although drink flowed freely. Asked once by the documentarian Bruce Ricker whether her family sent cases of their wines, Nica snorted crossly, “Better believe they don’t” and then added, “Just try and get a buck from them.” A casual observer might have wondered if Nica had made a deliberate break with the past or if perhaps her illustrious family had eschewed this wayward member.

But on closer examination, Nica had brought old traditions to America. The Rothschilds, particularly the women, were assiduous in helping those less fortunate and doing good works in the local community. In London’s Whitechapel, for example, the family funded synagogues, schools and modern housing. Because of the importance of having a good pair of shoes at a job interview, every pupil and graduate of a Rothschild free school was fitted for a new pair of boots annually. These charitable deeds were not acts of remote munificence; Emma and her granddaughters became personally involved with many cases.

Employees at Nica’s family home at Tring were the first in the country to enjoy free health care. Long before many grand houses had modern conveniences, every house on a Rothschild estate had indoor plumbing and sewage piping. Emma, Nica’s grandmother, made lists of some four hundred causes that she supported, ranging from estate building repairs to paying for the passage to Canada of a poor Jewish emigrant family’s pet lamb. Local causes included needlework guilds, choral societies, convalescent homes and the Tring Band of United Hope. Her daughter-in-law Roszika and granddaughters were also expected to get involved. On royal public holidays the local children would receive a commemorative mug filled with sweets and a bright new shilling. Their families could apply to Emma’s coal club in winter or for unemployment benefits. For a small subscription local people could qualify for free health care and nursing. All families had access to an allotment. In the words of one employee, “To work at Tring Park was insurance from cradle to grave.”

Like her grandmother and other Rothschild women, if Nica saw a person or an animal in need, she would try to help them. While most Rothschilds were systematic in their acts of charity, Nica was largely reactive. Toot Monk, who as a boy spent a lot of time with Nica, marvelled at her generosity. “I can’t tell you how many mercy missions to save musicians’ lives in every way she made,” he told me. “Whether we were going to a pawnshop to retrieve a guy’s instrument or going to buy groceries because someone didn’t have food, or going to a rent office to pay somebody’s rent because they were about to thrown on the street, or going to the hospital to visit somebody because they didn’t have anybody else to visit them. Or going to help somebody get some food, because their girlfriend just had a baby. Every aspect of human existence that I saw musicians deal with, I saw them lean on Nica, and I saw Nica respond: she was like Santa Claus and Mother Teresa all rolled up in one.”

Nica did not see her own behaviour as heroic. She told me, “I just saw that a lot of help was needed.” Her attempts to do good sometimes misfired, as she told Max Gordon, former owner of the Village Vanguard club. “I undertook the job of managing a jazz band, believe it or not. Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. Imagine! I thought I could help him and his men become more employable. Me! A manager! It was a disaster.” Perhaps remembering her grandmother’s policy of providing children with new shoes or giving men seeking employment a suit to wear to an interview, Nica went out and acquired six matching blue tuxedos for the Jazz Messengers. “I thought that would help them get jobs. I was out of my mind.”

One of the more menial regular tasks she took on was to drive musicians to and from performances. Her Bentley, loaded with players and their instruments, was a familiar sight cruising between the clubs and Weehawken. I will never forget being driven by her; few could.

Nica liked to maintain eye contact with her passenger at all times while holding the steering wheel with one hand and a cigarette in the other. It was incumbent on other drivers to make way, whatever side of the road Nica was on. Orrin Keepnews told me about a similar experience of his: “She was of the opinion that it was very rude to talk to somebody without looking at them, except she was driving the car and I was a passenger in the back seat. So it was a very hair-raising conversation and I do not believe I ever rode with her again.”

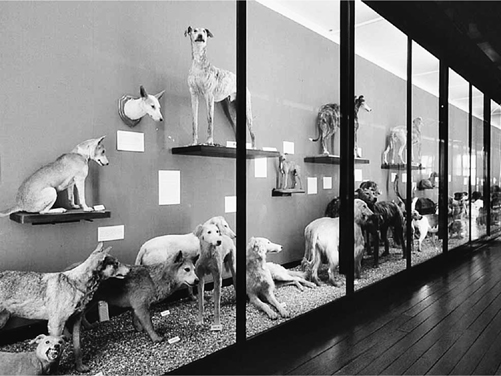

My overwhelming memory of Nica’s house in Weehawken was the cats. They were everywhere. The smell was almost overpowering. In some ways, the house was like an animated version of the private museum that her uncle Walter Rothschild had founded at Tring. Her childhood playground had been the secret magical place where Walter had installed his collection. From floor to ceiling, the walls were lined with glass cases containing stuffed animals from all over the world. Tigers, lions, leopards, gorillas, polar bears, minks, whales, elephants, hummingbirds, ostriches, antelopes, fleas, butterflies: all were on display. The whole of the top floor of one wing was devoted to every type of domesticated dog from a terrier to a Great Dane.

Nica’s house heaved with living cats. The ones I saw were the descendants of two valuable pedigree Siamese that had interbred with any passing New Jersey stray. The animals made a huge impression on Thelonious’s son Toot. “The house became this sanctuary for cats and there would be cats in every cupboard. There would be cats in the basement. There would be cats in the garage; there would be cats on the roof. We had a deal where I would count the cats and she would give me 50 cents for counting the cats. I remember I once counted, I think it was 306. That was the most I ever counted.”

Nica treated her cats rather like anyone else, being tolerant and welcoming to all but having her favourites in both human and feline form. Only the special cats, about forty in all, were allowed in her bedroom and she built barriers in Plexiglass to keep the riff-raff out.

Nica’s bedroom at the house in Weehawken (Photographic Credit 19.4)

Walter Rothschild’s collection of stuffed dogs (Photographic Credit 19.5)

“She knew the name of every single cat,” Monk’s saxophone player Paul Jeffrey told me. “All the cats were named after different musicians and she was very caring about these cats. One of her favourites was Cootie, named after Cootie Williams, the jazz musician. But the rest, well, they were multiplying all over the place.” Thelonious christened Nica’s new home “Catville.” Monk’s biographer Robin Kelley told me that Monk was not a cat lover. “He hated them, he absolutely hated them. But he loved her.”

I asked the producer Ira Gitler, a frequent visitor to Weehawken, whether Nica’s love of actual cats was in any way related to her love of musicians, or musical cats. Gitler laughed but didn’t take my question very seriously. “The term ‘cats’ in jazz comes from the cat houses of New Orleans where the musicians played in the early days. That’s how they started calling each other cats.” Gitler remembered that the only place Nica’s feline friends weren’t allowed was the Bentley. Nica had a fence built around the car in the garage so the cats could not scratch the paintwork or leather seats.

Nica’s love of cats didn’t stop at home. On the night I took my father and some friends to meet her, as we left the club she flipped open the trunk of the Bentley to reveal it was full of cat food. “I stop at certain places on my way home to feed some needy strays,” she explained.

Many will place Nica in a long line of eccentric British animal lovers who prefer their company to that of people. Sometimes I wonder whether Nica’s obsessive love of cats was a form of displaced maternal impulse. Although she did not live with her younger children, her letters are full of references to them and her excitement over their visits. One Christmas she wrote about painting the garage in yellow and white and making bunks for the children to sleep in. “It was the craziest ever,” she wrote to her friend Mary Lou Williams. Toot described the wonder of the mass family Christmas where the Monk family would join Nica’s and they would hang out around a tree groaning with presents.

In the spring of 1957, Monk finally regained his cabaret card and the right to play in alcohol-serving New York clubs. Almost immediately he got a gig at the Five Spot Café. Writing at that time, Joyce Johnson, Kerouac’s girlfriend, said:

The best place to end up was the Five Spot, which during the summer had materialised like an overnight miracle in a bar on Second Street and the Bowery, formerly frequented by bums. The new owners had cleaned it up a little, hauled in a piano and hung posters on the walls advertising Tenth Street gallery openings. The connection with the “scene” was clear from the beginning. Here for the price of a beer you could hear Coltrane or Thelonious Monk.

Nica decided that the piano was not good enough for Monk and bought the club a new one. The Five Spot paid Monk the quite princely sum of $600 a week, $225 of which he kept himself and the rest was divided between his three sidemen, who included the drummer Roy Haynes.

Although he has been a professional drummer since 1945, Roy Haynes was still sprightly and youthful at nearly eighty years old when we met in 2004. “When I did start to play with Monk at the Five Spot, it was Nica who called me up. She was the one who made the deal,” Haynes told me. “The money was very slim, but it was great to play with Monk. We were there for eighteen weeks at a time.”

Roy Haynes has clear memories of Nica and Monk sweeping into the club every night. Her arrival was preceded momentarily by a whiff of her favourite perfume, Jean Patou’s Joy, a scent powerful enough to cut through any cigarette smoke.

Thelonious was usually very late. We were supposed to start at nine. Sometimes he would get there at eleven or even later with the Baroness. They would walk in together and go right back into the kitchen, that was the hangout, and start making hamburgers. Sometimes Monk would come right in there and lie down on the table and go to sleep. He wouldn’t even talk, you know. Nica was responsible for getting him to the club but getting him on stage was not easy. When he was ready to wake up and play, he would come up and play his heart out.

Bundled up against the winter cold in a huge fur coat, Nica was often surrounded by a group of admirers. She sat in her favourite spot nearest the stage with a Bible on the table in front of her: the good book was a flask of whisky in disguise. Apart from the coat and a triple string of the finest pearls, Nica dressed simply, having long since stopped being bothered with couture or hairdressers. It was not her appearance but her demeanour that most struck Roy Haynes. “She was always smiling, you know. I will never forget that smile of hers.”

Nica captured a typical night at the club on her tape recorder. Introducing the evening in her inimitable gravelly voice, she says over the general clatter and chatter of the crowd, “Good evening, everybody, this is Nica’s tempo and tonight we are coming to you direct from the Five Spot Café and that beautiful music you hear is the Thelonious Monk quartet, Charlie Rouse on saxophone, Roy Haynes on drums and Ahmed Abdul-Malik on bass.” She pauses and the first strains of her tune, “Pannonica,” float over the ambient noise.

Then Monk starts to speak. “Hello, everybody, Thelonious Monk here. I’d like to play a little tune I composed not so long ago dedicated to this beautiful lady here. I think her father gave her that name after a butterfly he tried to catch. Don’t think he ever caught the butterfly but here’s the tune I composed for her, ‘Pannonica.’ ”

Monk’s star was ascending: he was recording and finally getting decent reviews. His manager Harry Colomby knew that there was a lot of ground to make up. “A Thelonious Monk album would sell ten thousand copies. Forget a million, forget platinum. Jazz was a limited world with a tiny audience. Thelonious Monk was listed in the phone book as: ‘Monk, Thelonious.’ Because they were poor, they wanted the phone [to be listed] for jobs.”

Colomby booked Monk to play a gig in Baltimore, Maryland. As the date got nearer, though, Monk’s close circle became nervous, because he was having one of his “mental episodes.” Colomby explained to me that periodically Monk would refuse to sleep for up to five days in a row. During that time he would wander the streets or stare catatonically out of the window, often shuffling from foot to foot, mumbling under his breath. Eventually he would fall into a deep sleep that would last twenty-four hours. Occasionally during an episode he destroyed things, objects rather than people. Once he tried to take a ceiling down in a hotel room. Another time he swept ashtrays off pianos and knocked over furniture.

Paul Jeffrey, Monk’s last saxophone player, was frequently recruited to watch Monk during one of his episodes. I asked him if he was ever frightened. Jeffrey shook his head. “The Baroness told me, ‘He will never hurt you.’ She was certain so I never worried.”

Nica, Monk and the Bebop Bentley, an S1 Continental convertible, outside the Five Spot Café in the Bowery, New York City, January 1, 1964 (Photographic Credit 19.6)

The only time Monk hurt Nica was falling off stage at the Village Vanguard and landing on his patroness. “He toppled over from the stage, on top of me, ’cause I was sitting on the table underneath,” she said, roaring with laughter.

Monk had not slept for three days before the job in Baltimore. “We weren’t in a position to cancel a job,” Colomby said. “It is easy to say now, why did we let him go? But we simply could not afford to cancel work. You just had to do it.”

*Al Timothy, Nica’s supposed lover, had come from London to New York to look for work. Nica helped him but there is no evidence that the couple were close at this time.