Nica was sixty-nine, soon to be a great-grandmother, and her life, free from caring for Monk, was at another crossroads. She could have gone home to a cottage on the estate at Ashton and lived with her sisters, or joined her daughter Janka, who had emigrated to Israel. Instead she stayed on in Weehawken, sharing the house with the pianist Barry Harris and all those cats.

Her routine hardly changed. Nica spent most of the day in bed surrounded by paperwork, books and magazines and cats. Her daily mission was to complete The Times crossword. She remained a night bird and seemed happier as dusk fell. One evening she and I arranged to meet. “Let’s meet at twelve,” she suggested.

“Just before lunch?” I asked: after all she was my great-aunt and already rather an old lady.

“No! Twelve midnight!” she roared.

I asked her grandson Steven if he called her Granny or another nickname. Without hesitating, he said, “Bye-Bye.”

Why?

“Because I would run into her room and make a noise and soon she would laugh and say, bye-bye.”

During 1984, Nica had radiation treatment for cancer but said music was the best therapy. It must have worked, for she kicked cancer as well as the hepatitis caught, as claimed by Nica, from her doctor’s dirty needles. The Nica I came to know a few years later lived much the same as she had thirty years earlier: it was Monkless but she was still an avid music follower. When I called her up on arriving in New York, she would laugh, say hello and then immediately fill me in on the news. It was never anything personal or revelatory, just unbridled excitement about what was happening musically: so-and-so is playing at this or that club. “It’ll be a hoot. Let’s meet there.” Then, typical of many Rothschilds, she would hang up without bothering to say goodbye.

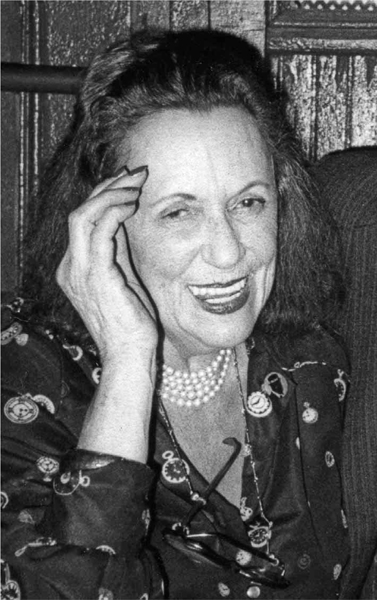

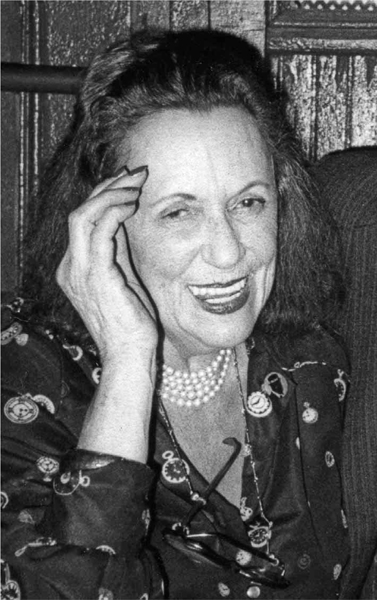

Nica in a New York jazz club in 1988 (Photographic Credit 23.2)

Nica continued to keep in touch with her British family. In England there were family reunions in 1968, 1969 and 1973, as well as others when family members passed through New York. In the archives at Waddesdon I found many references to Nica in family letters. I remember one large meeting at Ashton on May 6, 1986, when Miriam invited Nica, her children, Rabbi Julia Neuberger and myself to lunch. There were no introductions: everyone just piled in, disparate characters united by their not so disparate genes.

In a letter written to a Rothschild cousin on June 21, 1986, Miriam apologises for bringing Nica to a family function. “I hope that the idea of adding Nica to your dinner with my brother did not prove disastrous. Nica was keen to see you and since Thelonious died she has been very lonely and ill and very much wanted to see every member of the family before going back.” Following the event, Nica wrote to the cousin, apologising for arriving on “all fours”: she had recently fallen down and hurt herself. Soon afterwards she returned to New York on the QE2 with her daughter Berit, only to crack a rib once she got home: she had been trying to climb onto her roof to get a better view of the Tall Ships Race.

In 1986 Nica appeared in two films. Clint Eastwood’s Bird was a fictional account of the life of Charlie Parker based partly on Nica’s memories. Straight, No Chaser was a documentary that mixed archival footage of Monk and Nica with recent shots of Kingswood Road and Monk’s funeral. Nica took her children to meet Clint Eastwood at Nica’s Bar in the Stanhope Hotel. She loved the irony that the place that had once thrown her onto the streets was now honouring her memory. After the encounter Nica wrote to her friend Victor Metz in Paris: “Clint Eastwood seems to be REMARKABLY cool but I doubt I will like the way my ‘role’ is played. He sent me a picture of the actress and I thought she looked like a constipated horse!!!”

Quincy Jones saw Nica at the première: “She was with Barry Harris and we had a nice dinner after we saw the film. Barbra Streisand was my date that night. When we came out we had a limousine and twenty guys in two cars chasing us up Madison Avenue. Crazy.” What did Nica make of all this? “She was hip, she was cool.”

In November 1988, Nica was admitted to hospital for heart surgery. It was a straightforward procedure and she was expected to remain there for a few days. One of her last visitors was the pianist Joel Forrester. “Nica looked parchment white lying in her bed. She was covered up and was all by herself. She explained to me that she was incapable of reading and she couldn’t see me very well and yet she was fully conscious. There was no television for her to look at, you know, had she wanted to. I said, ‘Nica, what are you doing all day?’ She answered, ‘Picking over a lifetime of memories.’ ”

Nica was expected to make a full recovery, but her body, weakened by age, hard living, hepatitis, a few bad car crashes and a bout of cancer, gave up. At 5:03 p.m. on November 30, 1988, Nica died. She was seventy-four. The cause of death was given as heart failure during a triple aorta coronary bypass.

In her will, Nica left $750,000. She had complained of penury but it turned out to be relative. I thought about her tired old clothes, the frayed carpets, the lack of food and decent wine in the house, and realised that these were choices. The only luxuries Nica had wanted were her car, her Steinway piano and her Ping-Pong table. Everything else was functional. Only the Bentley was a crowd stopper. I wondered whether it was a coincidence that the one thing that cost a lot of money, a flash car, was an escape vehicle. Once she offered to sell her car to Thelonious for $19,000.

“Nineteen thousand dollars!” screamed Monk. “For that I can buy a home with four bedrooms, living room, kitchen and garage.”

“Of course you can,” Nica replied, “but where would it take you?”

Nica left one last request: that her family cremate her body, hire a boat and scatter her ashes on the Hudson River near “Catville.” The timing was very important: it had to be done ’round midnight.