Chapter 2

The Truth about Saturated Fat

Wonderful Results with Paleo: Marilyn’s Story

I started following this diet five weeks ago after it was recommended by an osteopath I was seeing. I am about to turn sixty-five and have been struggling with high blood pressure for about four years and elevated cholesterol for about fifteen years. Until very recently, I was taking 25 mg of a diuretic and 40 mg of lisinopril (a blood pressure drug).

The first two weeks on the diet were not easy, because I was especially weak until I adjusted my blood pressure medication, first cutting out my diuretic and then lowering the dosage of my lisinopril. I monitor my blood pressure daily, and with my doctor’s supervision I am now keeping it within a normal range, usually about 110/75, with only 10 mg of lisinopril daily.

As to my lipids, the change is remarkable. On March 7, 2006, my total cholesterol was 263, HDL was 48, and LDL was 158, with a ratio of 5.4. My triglycerides were 284. My results today: total cholesterol is 163 (in my entire life I have never been this low), with an HDL of 53, an LDL of 94, and a ratio of 3.1. My triglycerides are 76.

Prior to following this eating program, I was a fairly health-conscious person who exercised regularly, yet was never able to control my weight or other health issues. I tried for twenty years to lose my last ten pounds and was never successful. I have already lost at least eight pounds and hope to drop five more. Most important, I am very excited to finally find a program that keeps me off medication.

Blood Miracles: Sam’s Story

Dr. Cordain spoke last semester at the USAF Academy. I listened to his lecture, bought and read The Paleo Diet, and decided to try the diet myself, due to concerns about coronary artery disease. I had my lipid profile checked the day before starting the diet and again after two and a half weeks—I had dropped my total cholesterol by 66 points, and my total cholesterol was lower than my LDL had been when I started. (Total cholesterol 141, down from 207; LDL 86, down from 145; HDL 42, down from 44; risk factor 3.4, down from 4.7.)

Phenomenal!

If you are a Paleo Dieter or follow a low-carb diet, you know a storm has been brewing for some time about saturated fats. This question of saturated fats and disease has been hotly debated in recent years and has created a rift in both the Paleo and the scientific communities. My perspective on dietary saturated fat has changed substantially in the last decade as new data has arisen and as we gain a better understanding of atherosclerosis, the process that clogs arteries and promotes heart disease.

The correct answer to the saturated fat issue lies in the wisdom of our evolutionary past. By examining the dietary and lifestyle patterns of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, we can gain insight into this difficult problem. The evolutionary template allows us to peer into the future and provides us with the proper solution to complex dietary/health questions before any laboratory experiments are ever conducted. This powerful tool gives us a huge advantage. The Paleo evolutionary template allows us to connect the dots, piecing together and making sense of the scientific evidence so that we can truly understand how to eat for optimal health the way nature intended. To find an answer to the saturated fat problem, I examined the saturated fat intake of the world’s 229 hunter-gather societies and published the results of my analysis in 2006; the outcome changed the way I now view saturated fats.

Saturated Fat, Blood Cholesterol Levels, and Heart Disease

Let us critically evaluate both sides of the saturated fat argument. The traditional viewpoint is that dietary saturated fats raise blood cholesterol levels and increase our risk for heart disease. On the opposite side of the argument, a growing number of scientists, physicians, and writers now believe that dietary saturated fats have little or nothing to do with atherosclerosis and heart disease. Both factions strongly rely on epidemiological (population) studies to support their opposing viewpoints. Who’s right and who’s wrong? You may ask yourself how in the world could two seemingly well-informed and well-educated groups of scientists interpret similar studies in such different ways? And does it matter?

One of the reasons why epidemiological studies frequently yield conflicting results for identical topics is because of variables that cause confusion in the interpretation of the results. For example, although some studies have shown a link between animal protein consumption and symptoms of heart disease, it is entirely possible that this association was false because the measurement of animal protein was confounded by another variable also linked to heart disease symptoms: meat is a major source of animal protein in the U.S. diet, but it is also a major source of saturated fat. Because meat often comes as an inseparable package of protein plus saturated fat, animal protein is highly related to saturated fat, thereby making it difficult to separate the effects of saturated fat from those of animal protein.

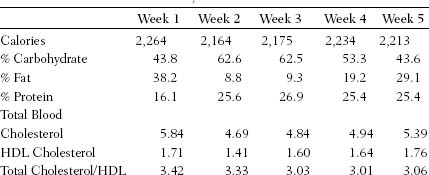

Given the shortcomings of epidemiological studies, human experimental studies are more helpful because they can separate factors and determine which specific variable may be causing certain effects. So is it the protein or the saturated fat that elicits heart disease symptoms? To answer this question, an experiment was conducted by Dr. Andy Sinclair and coworkers at Deakin University in Australia in 1990. Ten adults were fed a low-fat, lean beef–based diet for five weeks. Caloric intake was kept constant during the entire experiment. Total blood cholesterol concentrations fell significantly within one week of beginning the high-protein diet but rose as beef fat drippings were added back into the diet during weeks four and five. The authors concluded, “[I]t is the beef fat, not lean beef itself, that is associated with elevations in cholesterol concentrations.”

More research conducted during the last five years has confirmed that increases in dietary protein have a beneficial effect on our blood cholesterol and blood lipid profiles.

When most people align themselves with the saturated fat issue one way or another, they are frequently unaware that the term “saturated fat” is not a single item. Although most people know that saturated fats are concentrated in foods such as butter, eggs, lard, cheese, shortening, cream, fatty meats, and baked goods, few realize that not all saturated fats affect our blood cholesterol equally. There are four dietary saturated fats (actually, fatty acids) we need to concern ourselves with:

1. Lauric acid

2. Myristic acid

3. Palmitic acid

4. Stearic acid

Each of these dietary saturated fatty acids has slightly different effects on our blood.

Early studies supported the viewpoint that myristic acid and palmitic acid generally raised total blood cholesterol levels, whereas lauric acid did so slightly, and stearic acid didn’t increase it at all. In those days, it was routine to carry out nutritional experiments under meticulous “metabolic ward” conditions—meaning that the subjects could eat only the food provided to them and nothing else. All meals were designed to precisely control the types of fats consumed. Subjects who didn’t faithfully comply with the experimental diets were eliminated from the study.

The precision and accuracy of these early experiments are unquestionable, and the conclusion that saturated fats increase blood cholesterol is indisputable. As you will soon see, however, there are important limitations to these experiments that were unrecognized in their day. The most important shortcoming was that the endpoint variable that was measured—total blood cholesterol—was misleading and incomplete. We now realize that additional blood chemistry measurements are required to more accurately predict the risk of heart disease.

Total blood cholesterol levels are a crude marker for heart disease, as they don’t reflect the dynamics of cholesterol entering or leaving the bloodstream. Some cholesterol is taken out of our bodies by HDL (good) particles, while other cholesterol is deposited in our arteries by LDL (bad) particles and forms part of the plaque that clogs our arteries. Because total cholesterol represents a summation of both good (HDL) and bad (LDL) cholesterol, by itself it is a poor measure of heart disease risk. The total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio is a much better index for heart disease risk—and it is even more predictive if we know our general state of inflammation, which I cover in later chapters.

Lower values for the total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio reduce our risk for heart disease, whereas higher values increase it. Let’s go back and reevaluate Dr. Sinclair’s experiment, in which he fed subjects a low-fat, beef-based diet for five weeks and then added beef fat back into the subjects’ diets during weeks four and five—all the while keeping the calories constant. Remember that total blood cholesterol increased during weeks four and five after the beef fat drippings were added back in, leading the authors of the study to conclude that saturated fats raise total blood cholesterol. Dr. Sinclair didn’t report the total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio in his experiment, but it is easy to calculate these numbers, as I have done in the table below. As you can see, the addition of high-saturated-fat beef drippings worsened total blood cholesterol values but actually improved the total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio. If you were to look only at the total blood cholesterol values, it would appear as if saturated fats increased the risk for heart disease. And herein lies the problem with much of the human experimental studies conducted from the 1960s until the late 1980s—the single measurement of total cholesterol was an inappropriate and misleading endpoint.

Don’t get too excited about my reanalysis of Dr. Sinclair’s study. Remember, it is only a single experiment and, by itself, can’t overturn the dogma of thirty or more years of studies examining only total blood cholesterol as the endpoint risk factor for heart disease. What we really need to look at are analyses combining all experiments that have examined how saturated fats affect the total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio. Studies that combine the results from many experiments are called meta analyses. In addition, we can check out what meta analyses tell us about how the four different types of saturated fatty acids—lauric acid, myristic acid, palmitic acid, and stearic acid—affect the total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio, as well as other blood markers that increase heart disease risk.

How Dietary Changes Affect Your Cholesterol

Amazingly, these types of comprehensive meta analyses of human dietary interventions are few and far between. A recent meta analysis involving saturated fats and blood chemistry was published in 2010 by Drs. Micha and Mozaffarian of the Harvard School of Public Health. Let’s examine an important issue these authors have stirred up. If national nutritional policy dictates that dietary saturated fats should be slashed across the board for every man, woman, and child in the country, what should they be replaced with: carbohydrates, polyunsaturated fats, monounsaturated fats, or what? The default nutrient that the government decided on to replace saturated fats became carbohydrates—this official governmental dictate occurred with very little discussion or debate on the issue. Incredibly, this recommendation was never rigorously tested using human dietary interventions or meta analyses. It simply became the unquestioned national policy that was spoon-fed to our entire medical/health-care system for decades. The simplistic thinking of the day was that if carbs contained no saturated fats, how could they possibly be dangerous?

Now let’s take a look at the facts about saturated fats that should have been considered before national policy unilaterally rejected them. Drs. Micha and Mozaffarian’s 2010 meta analysis showed that when carbs were used to replace saturated fats, carbs increased the risk for heart disease by increasing blood triglycerides and lowering HDL cholesterol levels. More important, this comprehensive meta analysis showed that the substitution of carbs for saturated fats neither raised nor lowered the total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio. In effect, when compared to carbs, saturated fats were shown to be neutral and neither increased nor decreased the risk for heart disease. In addition, when individual saturated fatty acids were compared to carbs, it was demonstrated that lauric acid, myristic acid, and stearic acid actually lowered the total cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio. The authors concluded the most wide-ranging meta analysis on saturated fats and heart disease ever with this statement:

These meta-analyses suggest no overall effect of saturated fatty acid consumption on coronary heart disease events.

What a turn of events! The best science of 2010 with the most comprehensive database ever assembled flew in the face of more than forty to fifty years of public and private recommendations that we should severely reduce dietary saturated fats to diminish our risk for heart disease. From the time I was twenty until very recently, I grew up with dietary recommendations that were flawed. Fortunately for me, during the last twenty years I have not followed the USDA MyPyramid Guidelines, which were in effect until mid-2011, but rather have followed humanity’s original diet as my road map for optimal health and well-being.

So, should you go out and eat bacon, hot dogs, salami, and fatty processed meats until you can’t eat any more? Absolutely not. Processed meats are synthetic mixtures of meat and fat combined artificially at the meatpacker’s or the butcher’s whim with no regard for the true fatty acid profile of the wild animal carcasses our hunter-gatherer ancestors ate. In addition to their unnatural fatty acid profiles—high in omega 6 fatty acids, low in omega 3 fatty acids, and high in saturated fatty acids—processed fatty meats are chock full of the preservatives nitrites and nitrates, which are converted into potent cancer-causing nitrosamines in our guts. To make a bad situation worse, these unnatural meats are typically laced full of salt, high-fructose corn syrup, wheat, grains, and other additives that have multiple adverse health effects. In a 2010 meta analysis, scientists from the Harvard School of Public Health reported that red meat consumption was not associated with either heart disease or type 2 diabetes, whereas eating processed meats resulted in a 42 percent greater risk for heart disease and a 19 percent greater risk for type 2 diabetes.

Saturated Fats in Hunter-Gatherer Diets

In 2006, I published a chapter in a scientific book that essentially overturned my prior convictions about saturated fat and health. The correct science behind the saturated fat issue and heart disease did not happen overnight, and had I used the evolutionary template as my guide quite a bit earlier, I would have known that population-wide recommendations to reduce saturated fats were flawed. The U.S. Dietary Guidelines and the World Health Organization both recommend consuming less than 10 percent of our calories as saturated fats. The American Heart Association’s recommendations are lower still, advising us to get less than 7 percent of our daily calories as saturated fat. Let’s take a look at the evolutionary evidence and see how it compares to these official recommendations.

In 2001, I published a paper in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, in which my colleagues and I examined the dietary macronutrient (protein, fat, and carbohydrate) content in 229 hunter-gatherer societies. We showed that animal fare almost always made up the greater part of hunter-gatherers’ daily food intake. In fact, most (73 percent) of the world’s hunter-gatherers obtained more than 50 percent of their subsistence from hunted and fished animal foods. In contrast, only 14 percent of worldwide hunter-gatherers obtained more than 50 percent of their daily subsistence from plant foods. You can see from these numbers that our ancestors ate a lot of meat. It is possible to look at any nutrient, including saturated fats, using the same mathematical model I developed for this study.

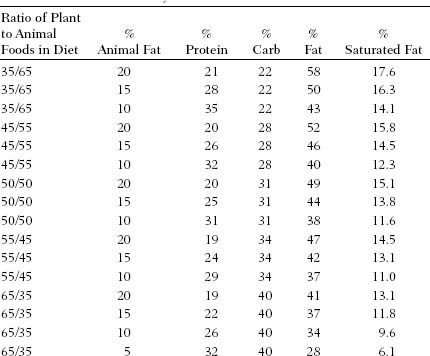

The results of this study are compiled in the following table. Notice that in my model I varied two factors: (1) the percentage of plant and animal foods in the diet and (2) the percentage of fat for the animal foods. These procedures allowed me to calculate the saturated fat in a wide range of hunter-gatherer diets. Finally, any combination of values that exceeded 35 percent protein was excluded, as protein is toxic above 35 percent of a person’s daily calories.

Saturated Fat Intake for Different Levels of Dietary Meats and Plant Foods

A few key points jump out from this table. First and foremost is the average dietary saturated fat intake, which comes in at 13.1 percent of the total calories. If we look at the typical hunter-gatherer diet, in which animal food consumption falls between 55 and 65 percent of the total calories, the dietary saturated fat intake is higher still at 15.1 percent. Even in plant-dominated hunter-gatherer diets, the dietary saturated fat (11.3 percent) is considerably higher than the American Heart Association’s recommended healthful values of less than 7 percent.

You can see that the normal dietary intake of saturated fats for historically studied hunter-gatherers likely accounted for 10 to 15 percent of their total energy. Values lower than 10 percent or higher than 15 percent would have been the exception, rather than the rule.

I cannot lend my support to population-wide recommendations to lower dietary saturated fat below 10 percent to reduce our risk for heart disease. This advice has little or no support from an evolutionary basis. Just as the replacement of saturated fat with carbohydrate was a poor idea that had not been adequately tested, studies of sufficient duration examining how low-saturated-fat diets may affect our health and well-being have never been carried out. They certainly don’t protect us from heart disease, and recommendations to reduce dietary saturated fats may potentially have adverse health consequences.

So my new advice for you is this: If you are faithful to the basic principles of the Paleo Diet, consumption of saturated fats within the range of 10 to15 percent of your daily calories will not increase your risk for heart disease. In fact, the opposite may be true, as new information suggests that elevations in LDL cholesterol may actually reduce systemic inflammation, a potent risk factor for heart disease. Consumption of fatty meats and organs had survival value in an earlier time, because fat provided a lot of energy and organs were rich in nutrients including iron, vitamin A, and the B-vitamins.

In Paleolithic times, humans didn’t eat grains, legumes, dairy products, refined sugars, and salty processed foods, the modern foods that produce chronic low-level inflammation in our bodies. Some medical studies now attribute many diseases, including heart disease, to chronic inflammation. Perhaps inflammation will prove to be more of a risk factor than high total cholesterol was thought to be.

Saturated fats have always been part of the ancestral human diet, and you should not avoid them when they are found in “real,” nonprocessed foods. The following table shows the sources of most of the saturated fats in the typical American diet. Notice that two-thirds of all of the saturated fats that Americans consume come from processed foods and dairy products. These are the foods you want to eliminate or restrict when you adopt the Paleo Diet. Remarkably, computerized dietary analyses from our laboratory show that despite their high meat content, modern-day Paleo diets actually contain lower quantities of saturated fats than are found in the typical U.S. diet.

| Sources of Saturated Fats | % of Total Saturated Fats |

| Non-Paleo Foods | |

| Milk, cheese, butter, and dairy | 20.0 |

| Processed foods with grains and beef (burritos, tacos, spaghetti) | 9.8 |

| Bread, cereals, rice, pasta, tortilla chips, potato chips | 9.5 |

| Desserts (ice cream, cakes) | 8.6 |

| Processed foods with grains and cheese (pizza, macaroni and cheese) | 6.9 |

| Beverages, miscellaneous | 3.7 |

| French fries, hash browns | 3.3 |

| Salad dressings | 3.0 |

| Margarine | 1.2 |

| Total | 66.0 |

| Paleo Foods | |

| Beef | 13.2 |

| Pork | 8.8 |

| Poultry | 6.0 |

| Eggs | 3.2 |

| Seafood | 1.8 |

| Total | 33.0 |

Stay away from saturated fats in processed foods. These artificial concoctions carry the baggage of refined grains, sugars, vegetable oils, trans fats, dairy, salt, preservatives, and additives that are definitely not good for our bodies. The saturated fats you consume from grass-fed beef, poultry, pork, eggs, fish, and seafood will not promote heart disease, cancer, or any chronic health problem. In fact, these foods can ensure your birthright—a long, healthy, and happy life.

Paleo Bottom Line

Not all saturated fats are created equal. Enjoy the right kinds and live a healthy, long life.