Chapter 3

Your Own Paleo Diet

Beating Metabolic Syndrome: Barbara’s Story

I have had high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and high triglycerides for years and was recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Just a few days later, I began the Paleo Diet, and within a week, my blood sugar dropped from the 200–300 range down into the 130–180 range. I am noticeably losing body fat, and I feel 100 percent better.

During the last three or four years since Paleo has become a household word, I have been interviewed a lot by the media and the popular press. The first question I often get asked is how the “caveman diet” works. Before I launch into my explanations, I correct the interviewer and make sure they know the Paleo Diet is also a nutritional plan for cavewomen and cave children. Then I say that the Paleo Diet is not really a “diet” at all, but rather a lifetime way of eating to maximize health and well-being to prevent and cure illnesses and diseases that run rampant in Westernized countries. I call the Paleo approach to nutrition Paleo diets (the foundation of the Paleo Diet).

With Paleo diets, we try to replicate the nutritional qualities in our ancestral hunter-gatherer diets by consuming the food groups they ate, chosen from common foods found in our local supermarkets, farmer’s markets, and grocery stores. What many people don’t completely understand is that Paleo diets are mimicking Stone Age diets but not exactly duplicating them. By reducing or eliminating refined sugars, processed foods, dairy products, cereal grains, and legumes (except occasionally, per the 85/15 rule), we can go a long way toward getting close to the nutrient characteristics of hunter-gatherer diets. Modern-day Paleo diets are composed of meats (grass-produced, preferably), fish, seafood, fresh fruits, veggies, nuts and seeds, and healthful oils. By replacing processed, feedlot-produced meats with grass-fed meats and free-range, organically fed poultry, we can get closer still to the original Stone Age diet.

The incredible cornucopia of fresh fruits, vegetables, meats, fish, seafood, and nuts that are routinely available year round in most major food stores in the Western world would be mind-boggling to any hunter-gatherer. On a daily basis, we can eat a luxuriously rich and diversified diet that most hunter-gatherers could only dream about. Modern-day Paleo diets could not have existed fifty to seventy-five years ago in most parts of the world. These diets are only possible now due to the advent of industrialization, refrigeration, modern agricultural practices, worldwide air transportation, and current technology. Let’s consider ourselves fortunate to live in these times.

Yet contemporary Paleo Dieters face a number of dietary issues that we need to consider as we adopt this lifetime nutritional plan. Here are a few:

- Hunter-gatherers typically did not eat three meals a day. Should we follow lockstep in their example?

- Hunter-gatherers ate only wild plant foods that were available seasonally from their local environment, whereas we can eat fresh fruits and vegetables all year round because of worldwide air transportation and various food-processing and agricultural practices.

- Hunter-gatherers certainly did not ingest pesticides, synthetic hormones, artificial sweeteners, or plastic compounds, but these items frequently find their way into present-day Paleo diets.

- Are there potential problems with our chemically treated water supply?

- We have the luxury to bake, broil, barbecue, microwave, fry, sauté, or cook our foods any way that we please—are there nutritional issues or concerns here?

The worldwide adoption of modern-day Paleo diets has been with us now for less than a decade, and clearly all of the answers to these questions have not been completely worked out. Let’s once again let the data speak for itself, however, and examine each of these topics from an evolutionary perspective.

The evolutionary template is an excellent way to answer complex questions of diet and health. The timing and the number of meals we should eat are controversial issues and not well understood. Many health-care professionals, as well as the lay press, state that consumption of smaller and more frequent meals is healthier than eating larger and less frequent meals. This advice is offered despite the lack of scientific evidence to justify it.

Studies examining the effects of meal frequency on health and body weight are inconclusive and have produced mixed results. Some studies show that skipping breakfast is unhealthy and may promote weight gain; other studies have shown that daily caloric intake was higher among women who ate breakfast compared to those who didn’t. Similarly, children who reported that they never ate breakfast had lower daily caloric intakes than regular breakfast eaters did. Furthermore, children who skipped breakfast lost more weight during a one-year period compared to daily breakfast eaters.

These kinds of controversies typify the chaos and disarray that are endemic in nutritional science. By placing the evolutionary template over the meal controversy fiasco, we can gain instant insight into the dietary patterns for which our species is genetically adapted. Yet before we get into the dietary patterns of hunter-gatherers, let’s see why the number of daily meals we eat can affect our health.

Caloric Restriction, Longevity, and Health

Numerous review papers from diverse research groups around the world are unanimous in their conclusion: caloric restriction increases life span and improves health. Caloric restriction by as little as 30 percent can increase life span by up to 40 percent in short-lived mammals such as rodents. To date, caloric restriction is the only intervention known to slow the rate of aging and increase life span in a variety of smaller animal species. Studies of caloric restriction in longer-lived primates such as the rhesus monkey were started in 1987. These ongoing experiments, though not yet complete, parallel the results of rodent studies and are predictive of an increased life span.

Perhaps more important than longevity are the beneficial health effects that caloric restriction has to offer. Caloric restriction improves virtually all indices of cardiovascular health—not only in lab animals but also in humans. In animal models, caloric restriction delays or prevents all types of cancers, kidney disease, diabetes, and autoimmune diseases and delays the age-related decline in wound healing, while improving immune function. Virtually all mechanisms that protect the body’s cells from injury remain at youthful levels longer during caloric restriction, including antioxidants, DNA repair mechanisms, protein turnover, corticosteroids, and heat shock proteins.

It is still not clear whether caloric restriction can extend life span in human beings, but some of the world’s longest-lived and healthiest people, the Okinawans, consume 20 percent fewer calories than adults on the Japanese mainland. Death rates for stroke, cancer, and heart disease were only 59 percent, 69 percent, and 59 percent, respectively, of those for the rest of Japan.

Does how many meals we eat influence our total caloric intake? During the fasting month of Ramadan, Muslims abstain from food and drink from dawn until sunset. Numerous studies demonstrate that this dietary pattern causes a spontaneous reduction in caloric intake and a slight weight loss. To date, no clinical studies have examined how a single large evening meal influences weight during the long term—six months or longer. The consumption of a single daily meal is a form of intermittent fasting, which in animals causes them to spontaneously reduce their caloric intake by 30 percent. In human studies, intermittent fasting reduces blood pressure, improves insulin sensitivity, improves kidney function, and increases resistance to disease and cancer.

I am currently in the process of compiling meal times and patterns in the world’s historically studied hunter-gatherers. If any single picture is beginning to surface, it clearly is not three meals per day plus snacking as per the typical U.S. grazing pattern. Here are a few examples:

1. The Ingalik hunter-gatherers of interior Alaska: The only meal of the day is eaten in the evening.

2. The Guayaki (Ache) hunter-gatherers of Paraguay: The evening meal is the most consistent of the day. This is understandable, because the day is generally spent hunting for food that will be eaten in the evening.

3. The !Kung hunter-gatherers of Botswana: Members move out of camp each day individually or in small groups to work through the surrounding range and return in the evening to pool the collected resources for the evening meal.

4. Hawaiians, Tahitians, Fijians, and other Oceanic peoples (pre-Westernization): Typically, meals, as defined by Westerners, were consumed once or twice a day. The main meal, usually freshly cooked, was generally eaten in the late afternoon after the day’s work was over.

From my ongoing analysis of hunter-gatherers, the most consistent daily eating pattern appears to be a single large meal consumed in the late afternoon or evening. A midday meal or lunch was rarely or never taken, and a small breakfast (consisting of the remainders of the previous evening meal) was sometimes eaten. Some snacking may have occurred during gathering; however, the bulk of the day’s food was consumed in the late afternoon or the evening. The hunter-gatherer pattern of eating could be described as intermittent fasting, compared to our Western customs, particularly when daily gathering or hunting was unsuccessful or marginal. There is wisdom in the ways of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, and perhaps it is time to rethink three squares a day.

Fresh produce is an absolutely essential component of modern-day Paleo diets, and my previous recommendations were for you to eat as much of these delicious foods as you like. This advice still holds true. The only banned vegetables are potatoes, cassava root, sweet corn, and legumes (beans, peas, soy, green beans, peanuts, etc.). Fruits are Mother Nature’s natural sweets, and the only fruits you should completely avoid are canned fruits packed in syrups. Dried fruits should be consumed in limited quantities, as they can contain as much concentrated sugar as a candy bar. See the following table for a comparison of the sugar content in fresh and dried fruits. If you are overweight or have one or more diseases of the metabolic syndrome (hypertension, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, or abnormal blood lipids), you should avoid dried fruit altogether and eat sparingly of “very high” and “high” sugar fruits.

Sugar Content in Dried and Fresh Fruits

| Dried Fruits | Total Sugars per 100 Grams |

| Extremely High in Total Sugars | |

| Dried mango | 73.0 |

| Raisins, golden | 70.6 |

| Zante currants | 70.6 |

| Raisins | 65.0 |

| Dates | 64.2 |

| Dried figs | 62.3 |

| Dried papaya | 53.5 |

| Dried pears | 49.0 |

| Dried peaches | 44.6 |

| Dried prunes | 44.0 |

| Dried apricots | 38.9 |

| Fresh Fruits | |

| Very High in Total Sugars | |

| Grapes | 18.1 |

| Banana | 15.6 |

| Mango | 14.8 |

| Cherries, sweet | 14.6 |

| High in Total Sugars | |

| Apple | 13.3 |

| Pineapple | 11.9 |

| Purple passion fruit | 11.2 |

Once your weight normalizes and your disease symptoms wane, feel free to eat as much fresh fruit as you like.

Domesticated versus Wild Produce

Of the many fruits and veggies that are available in the produce sections of our supermarkets, specialty food stores, and ethnic markets, most bear little resemblance to their wild ancestors. For instance, when you visualize a carrot, what do you see? Most likely, a large, bright-orange, tapering root. The wild version is tiny, thin, and perhaps not much bigger than your little finger. It is either black or dark or light purple, and frequently splits into multiple roots. Similarly, modern varieties of apples are big, sweet, and luscious, whereas the wild versions are more like crabapples—small, fibrous, and definitely not sweet. Almost all domesticated fruits and vegetables have been bred over thousands of years since the agricultural revolution to produce foods that are bigger, sweeter, and less fibrous. See the table below to compare the fiber content in wild versus cultivated plants.

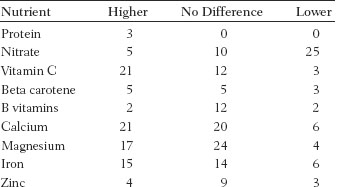

Is domesticated produce nutritionally inferior to wild plant foods? The table at the top of the next page contrasts the vitamin and mineral content of wild plant foods and their domesticated counterparts.

The B vitamins and iron and zinc concentrations are similar between the two, whereas wild plants have more calcium and magnesium. Cultured plants win out when it comes to vitamin C. Unless you are lucky enough to live in a part of the country where you can pick wild berries or gather wild asparagus, most of us will rarely eat wild plant foods. It really doesn’t matter, however, as the differences between wild and cultured plants are generally inconsequential.

Comparison of the Fiber Content of Wild and Cultivated Plants (100-gram samples)

| Wild | Cultivated | |

| Fruit | 8 grams | 3 grams |

| Roots | 8 grams | 2 grams |

| Bulbs | 8 grams | 3 grams |

| Legumes | 32 grams | 13 grams |

| Seeds/grains | 14 grams | 10 grams |

| Nuts | 11 grams | 7 grams |

| Leaves | 5 grams | 5 grams |

Comparison of the Vitamin and Mineral Content of Wild and Domesticated Plants

| Wild | Domesticated | |

| Vitamin B1 | 0.19 mg | 0.15 mg |

| Vitamin B2 | 0.11 mg | 0.10 mg |

| Vitamin C | 8.1 mg | 22.5 mg |

| Magnesium | 98 mg | 67 mg |

| Calcium | 117 mg | 49 mg |

| Iron | 7.6 mg | 7.4 mg |

| Zinc | 3.5 mg | 1.5 mg |

Organic versus Conventional Produce

Are there any advantages to organic produce? Should you pay the higher price? The table below shows the results of a study by Dr. Worthington that tabulated thirty-four scientific papers contrasting the nutrient content of organic versus conventionally grown produce.

The research has generally concluded that except for somewhat more vitamin C in organic vegetables (but not in fruit), no differences existed for any nutrient. So, if you’re considering buying organic produce for its superior vitamin and mineral qualities, it’s really not worth it.

Notice, though, that the concentration of nitrate in organic produce is consistently lower than in conventionally grown fruits and veggies. In addition, many studies have demonstrated reduced amounts of pesticides and toxic chemicals in organic produce. Higher environmental and dietary exposure to both pesticides and nitrates are associated with a greater risk for developing certain cancers. If this issue is of concern to you, then definitely go with organic produce, if you can afford it.

When you visit the produce section of your local supermarket, I’m sure you have noticed the glossy wax that is frequently present on cucumbers and apples and sometimes on bell peppers and other fruits and veggies. Have you wondered why these waxes were applied and whether they are safe? The purpose of fruit and vegetable waxes is to reduce shrinkage from water loss; to provide a barrier to gas exchange, which prolongs shelf life by simultaneously reducing the oxygen content and increasing the carbon dioxide content of the fruit or the vegetable; to improve appearance by adding a shiny film; and/or to provide a carrier for fungicides or other chemical agents to prevent microbial decay.

The waxes applied to fruits and vegetables can take on many different formulations. Listed below are five common waxing formulas:

1. 18.6% oxidized polyethylene, 3.4% oleic acid, 2.8% morpholine, 0.01% polydimethylsiloxane antifoam

2. 18.3% candelilla wax, 2.1% oleic acid, 2.4% morpholine, 0.02% polydimethylsiloxane antifoam

3. 9.5% shellac, 8.3% carnauba wax, 3.3% morpholine, 1.7% oleic acid, 0.17% ammonia, 0.01% polydimethylsiloxane antifoam

4. 19% shellac, 1.0% oleic acid, 4.4% morpholine, 0.3% ammonia, and 0.01% polydimethylsiloxane antifoam

5. 13.3% shellac, 3.0% whey protein isolate, 3.1% morpholine, 0.7% oleic acid, 0.2% ammonia, 0.01% polydimethylsiloxane antifoam

Not very appetizing, is it? It’s important that we take a closer look so that you can see the risks involved in consuming these waxes. Note that morpholine is a common element in most waxing formulas. This chemical is permitted for use in the United States, Australia, Canada, and other countries but not in Germany. The function of morpholine is to serve as a fungicide and as a solvent to help liquefy the wax.

By itself, in the low doses present in fruits and vegetables, this chemical probably does not constitute a health risk. During the digestive process, however, if there are nitrites (compounds found in processed meats and most vegetables) simultaneously present, morpholine is chemically changed into N-nitrosomorpholine (NMOR), a potent cancer-causing agent in rats and mice. The safe lower limit for NMOR is 4.3 ng (nanograms) per kg of body weight a day. It has been estimated that for adults, consuming waxed apples and a mixed diet, NMOR ingestion can approach 3.6 ng per kg of body weight a day, which represents the lower limit of safety.

These estimates did not actually measure NMOR formation in humans, though. Additionally, nitrite ingestion is quite variable, depending on your intake of vegetables and processed meats. It is entirely possible that regular consumption of waxed fruit and vegetables containing morpholine, along with the rest of your diet, could represent a significant cancer risk.

Notice that shellac is a major ingredient in three of the five most common formulas that are used to wax produce. Shellac comes from the hardened secretion of the female lac insect, which is native to India and Thailand and can be a potent allergen in some people, as can carnauba wax, which is also an ingredient in wax formulas.

Waxes cannot be removed by regular washing. If you prefer not to consume waxes, you must buy unwaxed produce or peel the fruit or the vegetable. Fruits and vegetables that are waxed include:

- Apples

- Avocados

- Bell peppers

- Cantaloupes

- Cucumbers

- Eggplants

- Grapefruits

- Lemons

- Limes

- Melons

- Oranges

- Parsnips

- Passion fruit

- Peaches

- Pineapples

- Pumpkins

- Rutabagas

- Squash

- Sweet potatoes

- Tomatoes

- Turnips

- Yucca

Because many of these fruits and vegetables are typically peeled and the peel is not consumed, only a few common fruits and vegetables present a problem.

Until recent times, fruits and vegetables were generally harvested when ripe and brought to market without wax coatings. Even today, fruit and vegetables can be harvested, packed, and stored without the use of waxes, and storage life can be extended through careful handling. The relative cancer risk of not eating fresh fruits and vegetables is much greater than the small risk posed by consuming waxed fruits and vegetables, but personally, I prefer my produce wax-free and as fresh as possible.

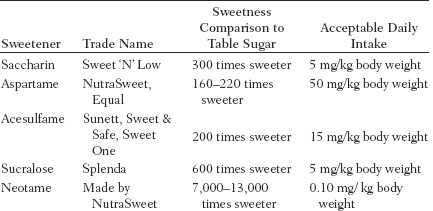

It’s pretty clear that if we follow the example of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, artificial sweeteners should not be part of contemporary Paleo diets. In my first book, I mentioned that beverages made with these substances were an acceptable replacement for high-fructose corn syrup sweetened sodas. I no longer can make this recommendation, based on some intriguing new population and animal studies that have been conducted recently.

Don’t forget the 85/15 rule, which allows you to occasionally consume food or drink that is normally off limits. I would never recommend that you drink these artificially sweetened beverages on a daily basis, though, and as I will soon show you, it is definitely not a good idea for pregnant women to ingest artificial sweeteners at all.

The table on page 34 lists the five artificial sweeteners that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved for consumption.

In addition, the FDA has sanctioned a sugar substitute, stevia, as a dietary supplement since 1995. Stevia is a crystalline substance made from the leaves of a plant native to Central and South America and is 100 to 300 times sweeter than table sugar. A new concentrated derivative of stevia leaves called rebaudioside A was authorized by the FDA in 2008 and goes by the trade names of Only Sweet, PureVia, Reb-A, Rebiana, SweetLeaf, and Truvia.

Since 1980, the number of people consuming artificially sweetened products in the United States has more than doubled. Today, at least forty-six million Americans regularly ingest foods and drinks sweetened by these chemicals—mainly in the form of soft drinks but also in a large number of other products, including baby food.

Most people know that soft drinks sweetened with sugar promote obesity, type 2 diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome (high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, and heart disease). And most people also believe that if we removed refined sugars from our diets and replaced them with artificial sweeteners, we would all be a lot healthier. A number of recent epidemiological and animal studies suggest that they are not part of the solution to the U.S. obesity epidemic but rather may be part of the problem. Unexpectedly, a series of large population-based studies, including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, have clearly demonstrated strong associations between the increased intake of artificial sweeteners and obesity and the metabolic syndrome, a cluster of health problems that includes high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and high blood glucose. Alarmingly, these effects have been observed in children, as well as in adults, and were utterly unanticipated because most artificial sweeteners were previously thought to be inert and not to react with our metabolism in an unsafe manner. Recent animal experiments conducted by Dr. Susan Swithers at Purdue have reversed these erroneous assumptions. Rats that were allowed to eat their normal chow consumed more food and gained more weight when artificial sweeteners were added to their diet. We do not currently know precisely how artificial sweeteners cause us to gain weight, but the most likely explanation is that they somehow interfere with our normal appetites and how our bodies handle both glucose and insulin.

Who would have thought that a mass-marketed product that was designed to help us lose weight may have actually caused exactly the opposite result? In 1958, the federal government deemed both saccharin and cyclamate “generally recognized as safe artificial sweeteners.” Eleven years later, the FDA banned cyclamate and announced its intention to ban saccharin in 1977 because of worries over increased cancer risks from both of these chemicals. Consumer protests eventually led to a congressional moratorium on the ban for saccharin, and it is still with us today. Aspartame was sanctioned for use as a sweetener by the FDA in 1982 for food and in 1983 for drinks, followed by sucralose in 1999, neotame in 2002, and acesulfame in 2003. You may think that any time chemical additives such as artificial sweeteners were permitted into our food supply, they would have been thoroughly tested and conclusively shown to be safe. Unfortunately, this is not always the case, and the potential toxicity of some of these sweetening compounds is widely disputed in the scientific community, particularly in the light of newer, more carefully controlled animal studies.

A series of experiments by Dr. Soffritti has shown that even low doses of aspartame given to rats during the course of their lives leads to increased cancer rates. This study is important, because many people may consume much higher concentrations of this chemical by drinking artificially sweetened beverages on a daily basis for years and years. Aspartame has also been shown to trigger migraine headaches in certain people because it breaks down into methanol—wood alcohol—in our bodies.

It’s not only aspartame that may prove dangerous to our health when we ingest these synthetic concoctions on a regular basis. Animal experiments by Dr. Bandyopadhyay have revealed that saccharin, acesulfame, and aspartame caused DNA damage in mice bone marrow. Frequently, it is difficult to translate results from animal experiments into meaningful recommendations for humans, because large epidemiological studies generally don’t show artificial sweeteners to be risk factors for cancer. Yet this does not mean that these compounds are completely safe.

A 2010 study of 59,334 pregnant women from Denmark showed for the first time that consumption of artificially sweetened soft drinks significantly increased the risk for pre-term delivery, at less than thirty-seven weeks. This condition shouldn’t be taken lightly, as it represents the leading cause of infant death. An interesting outcome of this study was that only artificially sweetened beverages increased the risk for pre-term delivery—and not sugar-sweetened soft drinks. I am not recommending that pregnant women consume sugary soft drinks, but this study indicates that they are much less harmful to your developing fetus than are artificially sweetened soft drinks. Any food additive that may cause migraine headaches, promote weight gain, and increase the risk for pre-term pregnancies should not be part of the Paleo Diet.

Cooking Advice for Contemporary Stone Agers

If you were to walk into your local physician’s or general practitioner’s office and ask him or her about the connection between nutrition and health, most doctors would toe the party line and tell you that a diet high in plant foods and low in animal proteins and fat is the way to go. If you were to ask your doctor about the glycemic index and how it influences your health, most would not have a good answer. It is not their fault—they simply were not taught this crucial dietary/health relationship in medical school. If you were to question your doctor about RAGEs, AGEs, and diet, almost none would know the answer. Although these terms are virtually unknown to most physicians, they have huge implications on our health and well-being that have only been recently recognized.

AGEs stands for advanced glycation end-products. These are compounds that naturally form in our bodies from the chemical reaction of sugars with proteins. If the concentration of AGEs becomes excessive in our bloodstream, they can cause damage to almost every tissue and organ in our bodies. In the past decade scientists have discovered that foods that contain AGEs may greatly contribute to the AGE burden in our bodies. The problem with AGEs is that they act like a key that permanently turns on low-level inflammation in our bodies by binding to cellular receptors known as RAGEs. AGEs also cross-link with proteins in our cells, altering their normal structure and function.

It is now becoming clear that high tissue levels of AGEs are associated with almost all chronic diseases that afflict us in the Western world. AGEs are directly involved with or accelerate the progression of numerous diseases, including the metabolic syndrome (type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease), kidney failure, Alzheimer’s disease, allergies and autoimmune diseases, cancers, cataracts, retinal degeneration, and gastrointestinal diseases. Additionally, excessive AGEs are known to speed up the aging process. In rodents, diets low in AGEs lengthen their life spans to the same degree that caloric restriction does. In human beings, restriction of dietary AGEs lowers markers of oxidative stress and inflammation. There is no reason to believe that our life spans cannot be increased in a manner similar to those of experimental animals by limiting our dietary AGEs.

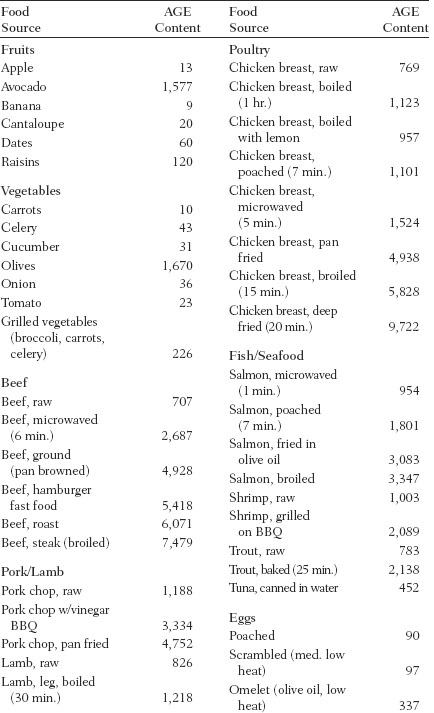

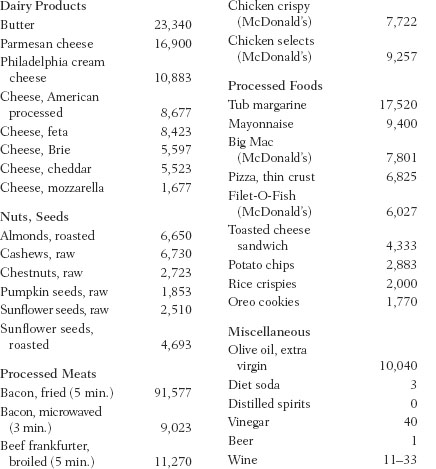

The good news is that if you are already following the Paleo Diet, you won’t have to tweak it much at all to make it a low-AGE diet. The following table lists the concentrations of AGEs found in many Paleo foods and in some non-Paleo foods. By closely examining this table, you can get a feel for foods that yield excessive AGEs and those that don’t.

Advanced Glycation End-Product (AGE) Contents in Foods (kU per 100 grams)

Although we don’t yet have clear guidelines regarding healthful dietary limits for AGEs, we do know that the typical American adult consumes about 14,700 kU of AGEs per day. Based on animal studies, if we can cut this number in half (7,350 kU per day), it may reduce inflammation and oxidative stress—and potentially increase our life spans. You can use the table to get an idea of your daily AGEs consumption.

An important element missing from this table is fructose. You remember that most Americans ingest this sugar in the form of processed foods, particularly soft drinks sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup. We also obtain fructose from the metabolism of table sugar (sucrose). When we digest sucrose, half of it is converted into fructose in our intestines. When all of these processed dietary sugars are added up, the average American consumes a staggering 59 pounds of fructose per year.

Because the concentration of AGEs in fructose is negligible (0–3 kU per 100 grams), you might think it is a minor contributor to our bodies’ total AGE load. Nothing could be further from the truth. Studies from Dr. Takeuchi’s laboratory at Hokuriku University in Japan show that fructose, once in our bodies, produces ten times more AGEs than the usual sugar found in our bloodstream, glucose, does. The message here is clear—although table sugar and high-fructose corn syrup contain virtually no AGEs, they dramatically elevate the concentrations of these noxious compounds in our bodies.

Notice that fruits and veggies and staples of the Paleo Diet are very low in AGEs, as are eggs. In contrast, most dairy products and fast and processed foods are loaded with these harmful substances. In their raw state, meat and seafood contain relatively few AGEs, but these chemicals become increasingly concentrated in our diets depending on the method of cooking.

I do not advocate that we always eat our meat and seafood raw—the risk for bacterial infection with E. coli and other bacterial contaminants is greatly magnified when we eat raw meat or seafood. Nevertheless, if you can find sources of untainted meats and seafood, eating these foods raw may represent a healthy alternative when it comes to AGEs. Sushi bars (raw fish and seafood) and restaurants serving steak tartare (raw beef) have been popular for decades.

Raw meats and fish contain much lower concentrations of AGEs, but so do animal foods that are prepared using slow cooking methods, and cooked meats are generally free from bacteria that may produce disease. As a Paleo Dieter, be aware that slow cooking methods, such as stewing, poaching, steaming, and slow roasting, reduce the AGE content of meats, while simultaneously preventing bacterial contamination.

When it comes to AGEs, the worst way to cook your meats and seafood is by high heat: searing, broiling, frying, and high-temperature roasting.

I would never be one to ruin a wonderful summer evening dinner at a close friend’s home by saying that I couldn’t eat the char-crusted barbecued London broil that my friend generously served onto my plate. By slicing off the burned surface and eating the pink inner layers, however, I can reduce my AGE intake nearly to the levels found in raw, uncooked beef. This is a table strategy that you may want to consider for all meats—being on the rare side is a good thing when it comes to AGEs.

Whenever possible, try to replace high-temperature searing techniques with long slow-cooking procedures. I love tender beef stew chunks slowly cooked all day long with carrots, celery, onions, and spices in a crock pot. Similarly, poached salmon with basil and tender, fresh asparagus don’t get much better for me. A final tip: cooking with lemon juice can significantly reduce the AGEs in your meat or fish, while simultaneously enhancing its flavor. Bon appetit.

Paleo Bottom Line

Attempt to emulate our Stone Age ancestors in the food groups they ate by choosing everyday foods available in grocery stores, farmer’s markets, and supermarkets. Avoid starches, processed foods, and overcooked meats.