Subjects and verbs are either singular or plural. The dog sees, or the dogs see. When one is singular, the other must be too. Plural nouns require the plural form of the verb. Pronouns must also agree with the words they replace. A female pronoun (such as she) can’t be used to replace a male noun. Indefinite pronouns, words such as some, none, and many, require singular or plural verbs, depending on their use. The situation gets even more complicated with pronouns such as everybody, which seem plural but are used in the singular form. Modifiers and phrases add to the complications. This section clarifies the concept of agreement and provides plenty of examples and practice to help you develop the requisite skills.

Addressing subject-verb agreement

The simplest form of subject-verb agreement deals with a clearly stated noun and verb.

The boy bites the dog.

The word boy is singular; the verb bites is singular. Everything is fine.

The boys bite the dog.

The word boys is plural; the verb bite is plural. Everything is fine here, too.

Conjunctions are used to join words, phrases and sentences. The conjunction and joins the two singular nouns and creates a plural. If “the boy and the girl” is the subject of the sentence, the conjunction and joins the two nouns and the sentence requires a plural verb.

The boy and the girl are doing their homework.

Other conjunctions don’t have that effect. Either/or and neither/nor don’t join the nouns in a way that requires a plural verb. In context, they separate the nouns, and the subject becomes “this or that” or “not this, not that” as in these examples:

- Neither the senator nor the aide has read the report.

- Either the son or the daughter is making dinner.

If one of the two nouns in such a phrase is plural, the verb agrees with the noun closest to the verb. If the sentence is a question and the verb comes before the nouns, the same proximity rule applies. If both nouns are plural, the verb must be plural.

- Neither the teacher nor the students have read the report.

- Is either the teacher or the students going to read the report?

- Neither the children nor Mother has made dinner.

- Have either the children or Mother made dinner?

- Neither the students nor the teachers are here.

Note this important exception: Some nouns are collective nouns, such as pride of lions, murder of crows (yes, that is really the collective noun for a bunch of crows), team of players, and group of people. The words pride, murder, team, and group represent a collection of members, whether lions or basketball players. However because these nouns refer to a single collection, they require a singular verb form.

Note this important exception: Some nouns are collective nouns, such as pride of lions, murder of crows (yes, that is really the collective noun for a bunch of crows), team of players, and group of people. The words pride, murder, team, and group represent a collection of members, whether lions or basketball players. However because these nouns refer to a single collection, they require a singular verb form.

Here’s a partial list of collective nouns, each of which is followed by one of its applications enclosed in parentheses:

- assembly (of worshippers)

- band (of monkeys)

- bed (of mussels)

- brood (of chicks)

- clan (of Scots)

- company (of soldiers)

- congress (of politicians)

- fleet (of ships)

- flock (of birds)

- group (of anything)

- herd (of animals)

- litter (of pups)

- mob (of people)

- nest (of birds)

- pack (of wolves)

- run (of fish)

- school (of fish)

- swarm (of bees)

- tribe (of baboons)

- troop (of Girl or Boy Scouts)

This isn’t a complete list by any means. You can use a search engine with the keywords “collective nouns” to find more examples.

Collective nouns either stand alone or combine with the preposition of, as in “The band approaches the river” or “The band of monkeys approaches the river.” A collective noun usually refers to a singular collection, as in “the school of fish” or “the fleet of destroyers,” and so requires a singular verb. The school of fish is fleeing the sharks. The fleet of destroyers is patrolling the Caribbean.

However, collective nouns can be plural as well. When more than one group or collection is involved, plural verbs are required.

- Three bands of apes were competing for the bananas left by the zookeeper.

- Two litters of pups were born at the vet’s at the same time.

Phrases that modify a subject can confuse the issue. These are common: as well as, along with, and other phrases that include with. They link to the subject but don’t change the verb to plural.

- The teacher, along with her students, is visiting the White House.

- The students, along with their teacher, are visiting the White House.

Words such as some of, all of, and a quarter of are used to quantify nouns.

- a quarter of the school

- all of the bills

- some of the cats

In these cases, the verb takes its number from the word after of, as in these examples:

- A quarter of the school has the flu.

- A quarter of the dogs are Golden Retrievers.

- All of the bill is his responsibility.

- All of the bills are his responsibility.

- Some of the cats are rescue cats from the local shelter.

- Some of the cat’s fur is purple.

You may also encounter a few special cases. When a sentence starts with a variation of here or there, the verb always takes its number from the nouns completing the sentence. The noun pants, and many others ending in s, such as measles, physics, and billiards are considered singular because they refer to one item: one particular disease, subject, or game. Sums and measurements are also treated as singular because they refer to a single item, even when the sum is many units. Others, including pants and glasses, are treated like plurals even though they refer to one object. Go figure. You just have to tune your ear to these exceptions and others like them:

- There are two cats in the room.

- There is no reason to behave that way.

- Here is the money I owe you.

- Here are the coupons you wanted.

- Measles is a dangerous disease.

- Social Studies is an interesting subject.

- My jeans are brand new. They are the only pair I bought.

- My glasses are always missing just when I need them most.

- Five hundred dollars a month is too much to pay for insurance.

Making subjects agree with verbs and pronouns agree with their antecedents

Making subjects agree with verbs and pronouns agree with their antecedents Picking the best word for the job

Picking the best word for the job Correcting common errors in sentence structure

Correcting common errors in sentence structure Making minor edits in capitalization and punctuation

Making minor edits in capitalization and punctuation Note this important exception: Some nouns are collective nouns, such as pride of lions, murder of crows (yes, that is really the collective noun for a bunch of crows), team of players, and group of people. The words pride, murder, team, and group represent a collection of members, whether lions or basketball players. However because these nouns refer to a single collection, they require a singular verb form.

Note this important exception: Some nouns are collective nouns, such as pride of lions, murder of crows (yes, that is really the collective noun for a bunch of crows), team of players, and group of people. The words pride, murder, team, and group represent a collection of members, whether lions or basketball players. However because these nouns refer to a single collection, they require a singular verb form. free.

free.

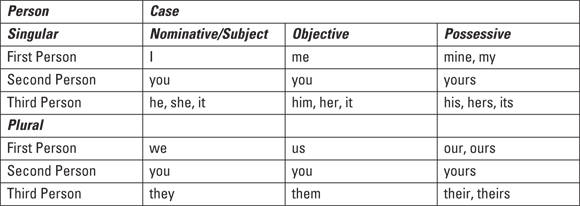

To clear up confusion about a pronoun when it appears with another pronoun, rephrase the sentence using only the pronoun you’re confused about. When you do that, the error becomes obvious:

To clear up confusion about a pronoun when it appears with another pronoun, rephrase the sentence using only the pronoun you’re confused about. When you do that, the error becomes obvious:  People commonly confuse who (nominative case) and whom (objective case). Just remember that who performs action and whom receives action.

People commonly confuse who (nominative case) and whom (objective case). Just remember that who performs action and whom receives action. was going to improve.

was going to improve.