TRIAL OF THE EMANCIPATORS OF COL. J.H. WHEELER'S SLAVES, JANE JOHNSON AND HER TWO LITTLE BOYS

Among other duties devolving on the Vigilance Committee when hearing of slaves brought into the State by their owners, was immediately to inform such persons that as they were not fugitives, but were brought into the State by their masters, they were entitled to their freedom without another moment's service, and that they could have the assistance of the Committee and the advice of counsel without charge, by simply availing themselves of these proffered favors.

Many slave-holders fully understood the law in this particular, and were also equally posted with regard to the vigilance of abolitionists. Consequently they avoided bringing slaves beyond Mason and Dixon's Line in traveling North. But some slave-holders were not thus mindful of the laws, or were too arrogant to take heed, as may be seen in the case of Colonel John H. Wheeler, of North Carolina, the United States Minister to Nicaragua. In passing through Philadelphia from Washington, one very warm July day in 1855, accompanied by three of his slaves, his high official equilibrium, as well as his assumed rights under the Constitution, received a terrible shock at the hands of the Committee. Therefore, for the readers of these pages, and in order to completely illustrate the various phases of the work of the Committee in the days of Slavery, this case, selected from many others, is a fitting one. However, for more than a brief recital of some of the more prominent incidents, it will not be possible to find room in this volume. And, indeed, the necessity of so doing is precluded by the fact that Mr. Williamson in justice to himself and the cause of freedom, with great pains and singular ability, gathered the most important facts bearing on his memorable trial and imprisonment, and published them in a neat volume for historical reference.

In order to bring fully before the reader the beginning of this interesting and exciting case, it seems only necessary to publish the subjoined letter, written by one of the actors in the drama, and addressed to the New York Tribune, and an additional paragraph which may be requisite to throw light on a special point, which Judge Kane decided was concealed in the "obstinate" breast of Passmore Williamson, as said Williamson persistently refused before the said Judge's court, to own that he had a knowledge of the mystery in question. After which, a brief glance at some of the more important points of the case must suffice.

LETTER COPIED FROM THE NEW YORK TRIBUNE

[Correspondence of The N.Y. Tribune.]

PHILADELPHIA, Monday, July 30, 1855.

As the public have not been made acquainted with the facts and particulars respecting the agency of Mr. Passmore Williamson and others, in relation to the slave case now agitating this city, and especially as the poor slave mother and her two sons have been so grossly misrepresented, I deem it my duty to lay the facts before you, for publication or otherwise, as you may think proper.

On Wednesday afternoon, week, at 4-1/2 o'clock, the following note was placed in my hands by a colored boy whom I had never before seen, to my recollection:

"MR. STILL — Sir: Will you come down to Bloodgood's Hotel as soon as possible — as there are three fugitive slaves here and they want liberty. Their master is here with them, on his way to New York."

The note was without date, and the signature so indistinctly written as not to be understood by me, having evidently been penned in a moment of haste.

Without delay I ran with the note to Mr. P. Williamson's office, Seventh and Arch, found him at his desk, and gave it to him, and after reading it, he remarked that he could not go down, as he had to go to Harrisburg that night on business — but he advised me to go, and to get the names of the slave-holder and the slaves, in order to telegraph to New York to have them arrested there, as no time remained to procure a writ of habeas corpus here.

I could not have been two minutes in Mr. W.'s office before starting in haste for the wharf. To my surprise, however, when I reached the wharf, there I found Mr. W., his mind having undergone a sudden change; he was soon on the spot.

I saw three or four colored persons in the hall at Bloodgood's, none of whom I recognized except the boy who brought me the note. Before having time for making inquiry some one said they had gone on board the boat. "Get their description," said Mr. W. I instantly inquired of one of the colored persons for the desired description, and was told that she was "a tall, dark woman, with two little boys."

Mr. W. and myself ran on board of the boat, looked among the passengers on the first deck, but saw them not. "They are up on the second deck," an unknown voice uttered. In a second we were in their presence. We approached the anxious-looking slave-mother with her two boys on her left-hand; close on her right sat an ill-favored white man having a cane in his hand which I took to be a sword-cane. (As to its being a sword-cane, however, I might have been mistaken.)

The first words to the mother were: "Are you traveling?" "Yes," was the prompt answer. "With whom?" She nodded her head toward the ill-favored man, signifying with him. Fidgeting on his seat, he said something, exactly what I do not now recollect. In reply I remarked: "Do they belong to you, Sir?" "Yes, they are in my charge," was his answer. Turning from him to the mother and her sons, in substance, and word for word, as near as I can remember, the following remarks were earnestly though calmly addressed by the individuals who rejoiced to meet them on free soil, and who felt unmistakably assured that they were justified by the laws of Pennsylvania as well as the Law of God, in informing them of their rights:

"You are entitled to your freedom according to the laws of Pennsylvania, having been brought into the State by your owner. If you prefer freedom to slavery, as we suppose everybody does, you have the chance to accept it now. Act calmly — don't be frightened by your master — you are as much entitled to your freedom as we are, or as he is — be determined and you need have no fears but that you will be protected by the law. Judges have time and again decided cases in this city and State similar to yours in favor of freedom! Of course, if you want to remain a slave with your master, we cannot force you to leave; we only want to make you sensible of your rights. Remember, if you lose this chance you may never get such another," etc.

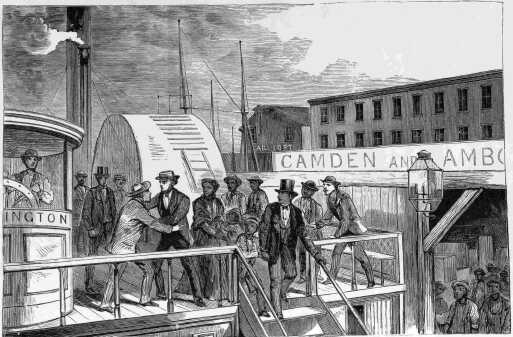

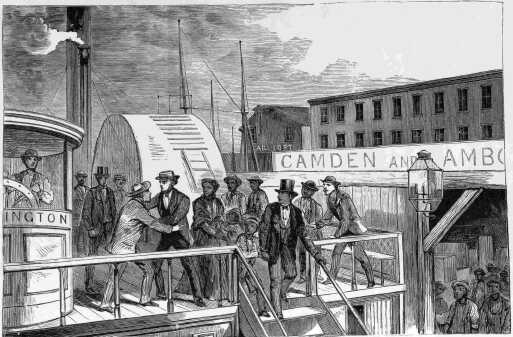

RESCUE OF JANE JOHNSON AND HER CHILDREN.

This advice to the woman was made in the hearing of a number of persons present, white and colored; and one elderly white gentleman of genteel address, who seemed to take much interest in what was going on, remarked that they would have the same chance for their freedom in New Jersey and New York as they then had — seeming to sympathize with the woman, etc.

During the few moments in which the above remarks were made, the slaveholder frequently interrupted — said she understood all about the laws making her free, and her right to leave if she wanted to; but contended that she did not want to leave — that she was on a visit to New York to see her friends — afterward wished to return to her three children whom she left in Virginia, from whom it would be HARD to separate her. Furthermore, he diligently tried to constrain her to say that she did not want to be interfered with — that she wanted to go with him — that she was on a visit to New York — had children in the South, etc.; but the woman's desire to be free was altogether too strong to allow her to make a single acknowledgment favorable to his wishes in the matter. On the contrary, she repeatedly said, distinctly and firmly, "I am not free, but I want my freedom — ALWAYS wanted to be free!! but he holds me."

While the slaveholder claimed that she belonged to him, he said that she was free! Again he said that he was going to give her her freedom, etc. When his eyes would be off of hers, such eagerness as her looks expressed, indicative of her entreaty that we would not forsake her and her little ones in their weakness, it had never been my lot to witness before, under any circumstances.

The last bell tolled! The last moment for further delay passed! The arm of the woman being slightly touched, accompanied with the word, "Come!" she instantly arose. "Go along — go along!" said some, who sympathized, to the boys, at the same time taking hold of their arms. By this time the parties were fairly moving toward the stairway leading to the deck below. Instantly on their starting, the slave-holder rushed at the woman and her children, to prevent their leaving; and, if I am not mistaken, he simultaneously took hold of the woman and Mr. Williamson, which resistance on his part caused Mr. W. to take hold of him and set him aside quickly.

The passengers were looking on all around, but none interfered in behalf of the slaveholder except one man, whom I took to be another slaveholder. He said harshly, "Let them alone; they are his property!'" The youngest boy, about 7 years of age — too young to know what these things meant — cried "Massa John! Massa John!" The elder boy, 11 years of age, took the matter more dispassionately, and the mother quite calmly. The mother and her sympathizers all moved down the stairs together in the presence of quite a number of spectators on the first deck and on the wharf, all of whom, as far as I was able to discern, seemed to look upon the whole affair with the greatest indifference. The woman and children were assisted, but not forced to leave. Nor were there any violence or threatenings as I saw or heard. The only words that I heard from any one of an objectionable character, were: "Knock him down; knock him down!" but who uttered it or who was meant I knew not, nor have I since been informed. However, if it was uttered by a colored man, I regret it, as there was not the slightest cause for such language, especially as the sympathies of the spectators and citizens seemed to justify the course pursued.

While passing off of the wharf and down Delaware-avenue to Dock st., and up Dock to Front, where a carriage was procured, the slaveholder and one police officer were of the party, if no more.

The youngest boy on being put in the carriage was told that he was "a fool for crying so after 'Massa John,' who would sell him if he ever caught him." Not another whine was heard on the subject.

The carriage drove down town slowly, the horses being fatigued and the weather intensely hot; the inmates were put out on Tenth street — not at any house — after which they soon found hospitable friends and quietude. The excitement of the moment having passed by, the mother seemed very cheerful, and rejoiced greatly that herself and boys had been, as she thought, so "providentially delivered from the house of bondage!" For the first time in her life she could look upon herself and children and feel free!

Having felt the iron in her heart for the best half of her days — having been sold with her children on the auction block — having had one of her children sold far away from her without hope of her seeing him again — she very naturally and wisely concluded to go to Canada, fearing if she remained in this city — as some assured her she could do with entire safety — that she might again find herself in the clutches of the tyrant from whom she had fled.

A few items of what she related concerning the character of her master may be interesting to the reader —

Within the last two years he had sold all his slaves — between thirty and forty in number — having purchased the present ones in that space of time. She said that before leaving Washington, coming on the cars, and at his father-in-law's in this city, a number of persons had told him that in bringing his slaves into Pennsylvania they would be free. When told at his father-in-law's, as she overheard it, that he "could not have done a worse thing," &c., he replied that "Jane would not leave him."

As much, however, as he affected to have such implicit confidence in Jane, he scarcely allowed her to be out of his presence a moment while in this city. To use Jane's own language, he was "on her heels every minute," fearing that some one might get to her ears the sweet music of freedom. By the way, Jane had it deep in her heart before leaving the South, and was bent on succeeding in New York, if disappointed in Philadelphia.

At Bloodgood's, after having been belated and left by the 2 o'clock train, while waiting for the 5 o'clock line, his appetite tempted her "master" to take a hasty dinner. So after placing Jane where he thought she would be pretty secure from "evil communications" from the colored waiters, and after giving her a double counselling, he made his way to the table; remained but a little while, however, before leaving to look after Jane; finding her composed, looking over a bannister near where he left her, he returned to the table again and finished his meal.

But, alas, for the slave-holder! Jane had her "top eye open," and in that brief space had appealed to the sympathies of a person whom she ventured to trust, saying, "I and my children are slaves, and we want liberty!" I am not certain, but suppose that person, in the goodness of his heart, was the cause of the note being sent to the Anti-Slavery office, and hence the result.

As to her going on to New York to see her friends, and wishing to return to her three children in the South, and his going to free her, &c., Jane declared repeatedly and very positively, that there was not a particle of truth in what her master said on these points. The truth is she had not the slightest hope of freedom through any act of his. She had only left one boy in the South, who had been sold far away, where she scarcely ever heard from him, indeed never expected to see him any more.

In appearance Jane is tall and well formed, high and large forehead, of genteel manners, chestnut color, and seems to possess, naturally, uncommon good sense, though of course she has never been allowed to read.

Thus I have given as truthful a report as I am capable of doing, of Jane and the circumstances connected with her deliverance.

W. STILL.

P.S. — Of the five colored porters who promptly appeared, with warm hearts throbbing in sympathy with the mother and her children, too much cannot be said in commendation. In the present case they acted nobly, whatever may be said of their general character, of which I know nothing. How human beings, who have ever tasted oppression, could have acted differently under the circumstances I cannot conceive.

The mystery alluded to, which the above letter did not contain, and which the court failed to make Mr. Williamson reveal, might have been truthfully explained in these words. The carriage was procured at the wharf, while Col. Wheeler and Mr. Williamson were debating the question relative to the action of the Committee, and at that instant, Jane and her two boys were invited into it and accompanied by the writer, who procured it, were driven down town, and on Tenth Street, below Lombard, the inmates were invited out of it, and the said conductor paid the driver and discharged him. For prudential reasons he took them to a temporary resting-place, where they could tarry until after dark; then they were invited to his own residence, where they were made welcome, and in due time forwarded East. Now, what disposition was made of them after they had left the wharf, while Williamson and Wheeler were discussing matters — (as was clearly sworn to by Passmore, in his answer to the writ of Habeas Corpus) — he Williamson did not know. That evening, before seeing the member of the Committee, with whom he acted in concert on the boat, and who had entire charge of Jane and her boys, he left for Harrisburg, to fulfill business engagements. The next morning his father (Thomas Williamson) brought the writ of Habeas Corpus (which had been served at Passmore's office after he left) to the Anti-Slavery Office. In his calm manner he handed it to the writer, at the same time remarking that "Passmore had gone to Harrisburg," and added, "thee had better attend to it" (the writ). Edward Hopper, Esq., was applied to with the writ, and in the absence of Mr. Williamson, appeared before the court, and stated "that the writ had not been served, as Mr. W. was out of town," etc.

After this statement, the Judge postponed further action until the next day. In the meanwhile, Mr. Williamson returned and found the writ awaiting him, and an agitated state of feeling throughout the city besides. Now it is very certain, that he did not seek to know from those in the secret, where Jane Johnson and her boys were taken after they left the wharf, or as to what disposition had been made of them, in any way; except to ask simply, "are they safe?" (and when told "yes," he smiled) consequently, he might have been examined for a week, by the most skillful lawyer, at the Philadelphia bar, but he could not have answered other than he did in making his return to the writ, before Judge Kane, namely: "That the persons named in the writ, nor either of them, are now nor was at the time of issuing of the writ, or the original writ, or at any other time in the custody, power, or possession of the respondent, nor by him confined or restrained; wherefore he cannot have the bodies," etc..

Thus, while Mr. W. was subjected to the severest trial of his devotion to Freedom, his noble bearing throughout, won for him the admiration and sympathy of the friends of humanity and liberty throughout the entire land, and in proof of his fidelity, he most cheerfully submitted to imprisonment rather than desert his principles. But the truth was not wanted in this instance by the enemies of Freedom; obedience to Slavery was demanded to satisfy the South. The opportunity seemed favorable for teaching abolitionists and negroes, that they had no right to interfere with a "chivalrous southern gentleman," while passing through Philadelphia with his slaves. Thus, to make an effective blow, all the pro-slavery elements of Philadelphia were brought into action, and matters looked for a time as though Slavery in this instance would have everything its own way. Passmore was locked up in prison on the flimsy pretext of contempt of court, and true bills were found against him and half a dozen colored men, charging them with "riot," "forcible abduction," and "assault and battery," and there was no lack of hard swearing on the part of Col. Wheeler and his pro-slavery sympathizers in substantiation of these grave charges. But the pro-slaveryites had counted without their host — Passmore would not yield an inch, but stood as firmly by his principles in prison, as he did on the boat. Indeed, it was soon evident, that his resolute course was bringing floods of sympathy from the ablest and best minds throughout the North. On the other hand, the occasion was rapidly awakening thousands daily, who had hitherto manifested little or no interest at all on the subject, to the wrongs of the slave.

It was soon discovered by the "chivalry" that keeping Mr. Williamson in prison would indirectly greatly aid the cause of Freedom — that every day he remained would make numerous converts to the cause of liberty; that Mr. Williamson was doing ten-fold more in prison for the cause of universal liberty than he could possibly do while pursuing his ordinary vocation.

With regard to the colored men under bonds, Col. Wheeler and his satellites felt very confident that there was no room for them to escape. They must have had reason so to think, judging from the hard swearing they did, before the committing magistrate. Consequently, in the order of events, while Passmore was still in prison, receiving visits from hosts of friends, and letters of sympathy from all parts of the North, William Still, William Curtis, James P. Braddock, John Ballard, James Martin and Isaiah Moore, were brought into court for trial. The first name on the list in the proceedings of the court was called up first.

Against this individual, it was pretty well understood by the friends of the slave, that no lack of pains and false swearing would be resorted to on the part of Wheeler and his witnesses, to gain a verdict.

Mr. McKim and other noted abolitionists managing the defense, were equally alive to the importance of overwhelming the enemy in this particular issue. The Hon. Charles Gibbons, was engaged to defend William Still, and William S. Pierce, Esq., and William B. Birney, Esq., the other five colored defendants.

In order to make the victory complete, the anti-slavery friends deemed it of the highest importance to have Jane Johnson in court, to face her master, and under oath to sweep away his "refuge of lies," with regard to her being "abducted," and her unwillingness to "leave her master," etc. So Mr. McKim and the friends very privately arranged to have Jane Johnson on hand at the opening of the defense.

Mrs. Lucretia Mott, Mrs. McKim, Miss Sarah Pugh and Mrs. Plumly, volunteered to accompany this poor slave mother to the court-house and to occupy seats by her side, while she should face her master, and boldly, on oath, contradict all his hard swearing. A better subject for the occasion than Jane, could not have been desired. She entered the court room veiled, and of course was not known by the crowd, as pains had been taken to keep the public in ignorance of the fact, that she was to be brought on to bear witness. So that, at the conclusion of the second witness on the part of the defense, "Jane Johnson" was called for, in a shrill voice. Deliberately, Jane arose and answered, in a lady-like manner to her name, and was then the observed of all observers. Never before had such a scene been witnessed in Philadelphia. It was indescribable. Substantially, her testimony on this occasion, was in keeping with the subjoined affidavit, which was as follows —

"State of New York, City and County of New York.

"Jane Johnson being sworn, makes oath and says —

"My name is Jane — Jane Johnson; I was the slave of Mr. Wheeler of Washington; he bought me and my two children, about two years ago, of Mr. Cornelius Crew, of Richmond, Va.; my youngest child is between six and seven years old, the other between ten and eleven; I have one other child only, and he is in Richmond; I have not seen him for about two years; never expect to see him again; Mr. Wheeler brought me and my two children to Philadelphia, on the way to Nicaragua, to wait on his wife; I didn't want to go without my two children, and he consented to take them; we came to Philadelphia by the cars; stopped at Mr. Sully's, Mr. Wheeler's father-in-law, a few moments; then went to the steamboat for New York at 2 o'clock, but were too late; we went into Bloodgood's Hotel; Mr. Wheeler went to dinner; Mr. Wheeler had told me in Washington to have nothing to say to colored persons, and if any of them spoke to me, to say I was a free woman traveling with a minister; we staid at Bloodgood's till 5 o'clock; Mr. Wheeler kept his eye on me all the time except when he was at dinner; he left his dinner to come and see if I was safe, and then went back again; while he was at dinner, I saw a colored woman and told her I was a slave woman, that my master had told me not to speak to colored people, and that if any of them spoke to me to say that I was free; but I am not free; but I want to be free; she said: 'poor thing, I pity you;' after that I saw a colored man and said the same thing to him, he said he would telegraph to New York, and two men would meet me at 9 o'clock and take me with them; after that we went on board the boat, Mr. Wheeler sat beside me on the deck; I saw a colored gentleman come on board, he beckoned to me; I nodded my head, and could not go; Mr. Wheeler was beside me and I was afraid; a white gentleman then came and said to Mr. Wheeler, 'I want to speak to your servant, and tell her of her rights;' Mr. Wheeler rose and said, 'If you have anything to say, say it to me — she knows her rights;' the white gentleman asked me if I wanted to be free; I said 'I do, but I belong to this gentleman and I can't have it;' he replied, 'Yes, you can, come with us, you are as free as your master, if you want your freedom come now; if you go back to Washington you may never get it;' I rose to go, Mr. Wheeler spoke, and said, 'I will give you your freedom,' but he had never promised it before, and I knew he would never give it to me; the white gentleman held out his hand and I went toward him; I was ready for the word before it was given me; I took the children by the hands, who both cried, for they were frightened, but both stopped when they got on shore; a colored man carried the little one, I led the other by the hand. We walked down the street till we got to a hack; nobody forced me away; nobody pulled me, and nobody led me; I went away of my own free will; I always wished to be free and meant to be free when I came North; I hardly expected it in Philadelphia, but I thought I should get free in New York; I have been comfortable and happy since I left Mr. Wheeler, and so are the children; I don't want to go back; I could have gone in Philadelphia if I had wanted to; I could go now; but I had rather die than go back. I wish to make this statement before a magistrate, because I understand that Mr. Williamson is in prison on my account, and I hope the truth may be of benefit to him."

JANE [her X mark.] JOHNSON.

JANE JOHNSON

PASSMORE WILLIAMSON.

It might have been supposed that her honest and straightforward testimony would have been sufficient to cause even the most relentless slaveholder to abandon at once a pursuit so monstrous and utterly hopeless as Wheeler's was. But although he was sadly confused and put to shame, he hung on to the "lost cause" tenaciously. And his counsel, David Webster, Esq., and the United States District Attorney, Vandyke, completely imbued with the pro-slavery spirit, were equally as unyielding. And thus, with a zeal befitting the most worthy object imaginable, they labored with untiring effort to convict the colored men.

By this policy, however, the counsel for the defense was doubly aroused. Mr. Gibbons, in the most eloquent and indignant strains, perfectly annihilated the "distinguished Colonel John H. Wheeler, United States Minister Plenipotentiary near the Island of Nicaragua," taking special pains to ring the changes repeatedly on his long appellations. Mr. Gibbons appeared to be precisely in the right mood to make himself surpassingly forcible and eloquent, on whatever point of law he chose to touch bearing on the case; or in whatever direction he chose to glance at the injustice and cruelty of the South. Most vividly did he draw the contrast between the States of "Georgia" and "Pennsylvania," with regard to the atrocious laws of Georgia. Scarcely less vivid is the impression after a lapse of sixteen years, than when this eloquent speech was made. With the District Attorney, Wm. B. Mann, Esq., and his Honor, Judge Kelley, the defendants had no cause to complain. Throughout the entire proceedings, they had reason to feel, that neither of these officials sympathized in the least with Wheeler or Slavery. Indeed in the Judge's charge and also in the District Attorney's closing speech the ring of freedom could be distinctly heard — much more so than was agreeable to Wheeler and his Pro-Slavery sympathizers. The case of Wm. Still ended in his acquittal; the other five colored men were taken up in order. And it is scarcely necessary to say that Messrs. Peirce and Birney did full justice to all concerned. Mr. Peirce, especially, was one of the oldest, ablest and most faithful lawyers to the slave of the Philadelphia Bar. He never was known, it may safely be said, to hesitate in the darkest days of Slavery to give his time and talents to the fugitive, even in the most hopeless cases, and when, from the unpopularity of such a course, serious sacrifices would be likely to result. Consequently he was but at home in this case, and most nobly did he defend his clients, with the same earnestness that a man would defend his fireside against the approach of burglars. At the conclusion of the trial, the jury returned a verdict of "not guilty," as to all the persons in the first count, charging them with riot. In the second count, charging them with "Assault and Battery" (on Col. Wheeler) Ballard and Curtis were found "guilty," the rest "not guilty." The guilty were given about a week in jail. Thus ended this act in the Wheeler drama.

The following extract is taken from the correspondence of the New York Tribune touching Jane Johnson's presence in the court, and will be interesting on that account:

"But it was a bold and perilous move on the part of her friends, and the deepest apprehensions were felt for a while, for the result. The United States Marshal was there with his warrant and an extra force to execute it. The officers of the court and other State officers were there to protect the witness and vindicate the laws of the State. Vandyke, the United States District Attorney, swore he would take her. The State officers swore he should not, and for a while it seemed that nothing could avert a bloody scene. It was expected that the conflict would take place at the door, when she should leave the room, so that when she and her friends went out, and for some time after, the most intense suspense pervaded the court-room. She was, however, allowed to enter the carriage that awaited her without disturbance. She was accompanied by Mr. McKim, Secretary of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, Lucretia Mott and George Corson, one of our most manly and intrepid police officers. The carriage was followed by another filled with officers as a guard; and thus escorted she was taken back in safety to the house from which she had been brought. Her title to Freedom under the laws of the State will hardly again be brought into question."

Mr. Williamson was committed to prison by Judge Kane for contempt of Court, on the 27th day of July, 1855, and was released on the 3d day of November the same year, having gained, in the estimation of the friends of Freedom every where, a triumph and a fame which but few men in the great moral battle for Freedom could claim.