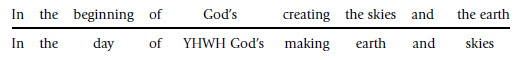

1In the beginning of God’s creating the skies and the earth

![]()

![]()

![]()

1:1. In the beginning of God’s creating the skies and the earth. Rashi began his commentary with the remark that the Torah could have begun with the first commandment to Israel—the commandment to observe Passover—which does not come until Exodus 12, rather than with creation. He answered that it begins with creation in order to establish God’s ownership of all the world—and therefore God’s right to give the promised land to Israel. I suggest that the lesson that we learn from the fact that the Torah does not begin with the first commandment is precisely that the commandments are not the sole purpose of the Torah. The Torah’s story is no less important than the commandments that it contains. Law in the Bible is never given separately from history. The Ten Commandments do not begin with the first “Thou shalt” but with the historical fact that “I brought you out of the land of Egypt …”

Another lesson is that, in the Torah, the divine bond with Israel is ultimately tied to the divine relationship with all of humankind. (Rashi did not refer to the first commandment, which is “Be fruitful and multiply” and is given to all humankind, but rather to the first commandment to Israel, which is Passover.) The first eleven chapters establish a connection between God and the entire universe. They depict the formation of a relationship between the creator and all the families of the earth. This relationship will remain as the crucial background to the story of Israel that will take up the rest of the Torah.

1:1. In the beginning of God’s creating the skies and the earth. The Torah begins with two pictures of the creation. The first (Gen 1:1–2:3) is a universal conception. The second (2:4–25) is more down-to-earth. The first has a cosmic feeling about it. Few other passages in the Hebrew Bible generate this feeling. The concern of the Hebrew Bible generally is history, not the cosmos, but Genesis 1 is an exception. There is a power about this portrait of a transcendent God constructing the skies and earth in an ordered seven-day series. In it, the stages of the fashioning of the heavenly bodies above are mixed with the fashioning of the land and seas below.

The translation of the Torah’s first phrase is a classic problem. Even at the risk of a slightly awkward English, I have translated this line literally, not only to make it reflect the Hebrew, but to show the significant parallel between this opening and the opening of the second picture of creation in Gen 2:4, thus:

(The second line is translated slightly differently above because it is not possible to reproduce the doubled divine identification, YHWH God, with a possessive in English.) Note that this first, universal conception puts the skies first, while the second, more earthly account starts with earth.

—2when the earth had been shapeless and formless, and darkness was on the face of the deep, and God’s spirit was hovering on the face of the water—

![]()

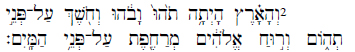

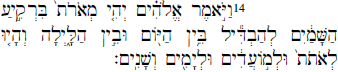

1:2. the earth had been. Here is a case in which a tiny point of grammar makes a difference for theology. In the Hebrew of this verse, the noun comes before the verb (in the perfect form). This is now known to be the way of conveying the past perfect in Biblical Hebrew. This point of grammar means that this verse does not mean “the earth was shapeless and formless”—referring to the condition of the earth starting the instant after it was created. This verse rather means that “the earth had been shapeless and formless”—that is, it had already existed in this shapeless condition prior to the creation. Creation of matter in the Torah is not out of nothing (creatio ex nihilo), as many have claimed. And the Torah is not claiming to be telling events from the beginning of time.

1:2. shapeless and formless. The two words in the Hebrew, t![]() h

h![]() and b

and b![]() h

h![]() , are understood to mean virtually the same thing. This is the first appearance in the Torah of a phenomenon in biblical language known as hendiadys, in which two connected words are used to signify one thing. (“Wine and beer” [Lev 10:9] may be a hendiadys as well, or it may be a merism, a similar construction in which two words are used to signify a totality; so that “wine and beer” means all alcoholic beverages.) The hendiadys of “t

, are understood to mean virtually the same thing. This is the first appearance in the Torah of a phenomenon in biblical language known as hendiadys, in which two connected words are used to signify one thing. (“Wine and beer” [Lev 10:9] may be a hendiadys as well, or it may be a merism, a similar construction in which two words are used to signify a totality; so that “wine and beer” means all alcoholic beverages.) The hendiadys of “t![]() h

h![]() and b

and b![]() h

h![]() ,” plus the references to the deep and the water, yields a picture of an undifferentiated, shapeless fluid that had existed prior to creation.

,” plus the references to the deep and the water, yields a picture of an undifferentiated, shapeless fluid that had existed prior to creation.

1:2. God’s spirit. Or “wind of God.” Words for “soul” or “spirit” in Hebrew frequently denote wind or breath (likewise in Greek: pneuma means both wind and spirit). This suggests that, in the ancient world, life was associated, in the first place, with respiration, as opposed to later determinations of life in terms of blood circulation or brain activity. Thus the animation of the first human will be described this way: “And He blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and the human became a living being.”

1:2. God’s spirit/wind hovering on the face of the water. The parallel with the ancient pagan creation myth of the wind god (Enlil, or Marduk) defeating the goddess of the waters (Tiamat; compare Hebrew t![]() hôm, translated “the deep,” in this verse) is striking. The difference between the two is striking, too: in the Torah the water and all other components of the universe are no longer regarded as gods. Nature is demythologized.

hôm, translated “the deep,” in this verse) is striking. The difference between the two is striking, too: in the Torah the water and all other components of the universe are no longer regarded as gods. Nature is demythologized.

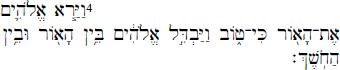

3God said, “Let there be light.” And there was light.

![]()

![]()

1:3. Let there be light. God creates light simply by saying the words: “Let there be” (the Hebrew jussive). Only light is expressly created from nothing (creatio ex nihilo). All other elements of creation may possibly be formed out of preexisting matter, that is, from the initially undifferentiated chaos. Thus God later says, “Let there be a space,” but the text then adds, “And God made the space.” And God says, “Let there be sources of light,” but the text adds, “And God made the sources of light.” So we cannot understand these things to be formed simply by the words “Let there be.” Now we can appreciate the importance of understanding the Torah’s first words correctly: The Torah does not claim to report everything that has occurred since the beginning of space and time. It does not say, “In the beginning, God created the skies and the earth.” It rather says, “In the beginning of God’s creating the skies and the earth, when the earth had been shapeless and formless …” That is, there is preexisting matter, which is in a state of watery chaos. Subsequent matter—dry land, heavenly bodies, plants, animals—may be formed out of this undifferentiated fluid. In Greece, the first philosopher, Thales, later proposed such a concept, that all things derive from water. Examples from other cultures could be cited as well. There appears to be an essential human feeling that everything derives originally from water, which is hardly surprising given that we—and all life on this planet—did in fact proceed from water.

4And God saw the light, that it was good, and God separated between the light and the darkness.

![]()

1:4. God separated. Initially there is only the watery chaos: shapeless and formless. Then creation is the making of distinctions: “And God separated between the light and the darkness,” “And separated between the water that was under the space and the water that was above the space.” Then more distinctions: between dry land and seas, among plants and animals “each according to its kind,” between day and night, and so on. In each case, creation is the act of separating a thing from the rest of matter and then giving it a name.

5And God called the light “day” and called the darkness “night.” And there was evening, and there was morning: one day.

![]()

![]()

1:5. God called the light “day” and called the darkness “night.” The first day also includes the creation of the ordering of time. Before the invention of day and night, time no less than space would be undifferentiated: “formless.” Light, the one thing that is totally ex nihilo, is thus essential to all that follows: the separating between light and dark in an ordered arrangement initiates a sequence of distinctions of time and space, and these distinctions embody creation.

1:5. And there was evening, and there was morning. It is sometimes claimed mistakenly that Genesis 1 is poetry. True, the wording is powerful and beautiful, and the recurring words “And there was evening, and there was morning” and the chronology that they reflect lend a formulaic order to the chapter. But that does not make the text poetry. It is prose.

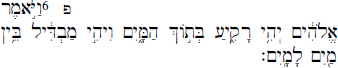

6And God said, “Let there be a space within the water, and let it separate between water and water.”

![]()

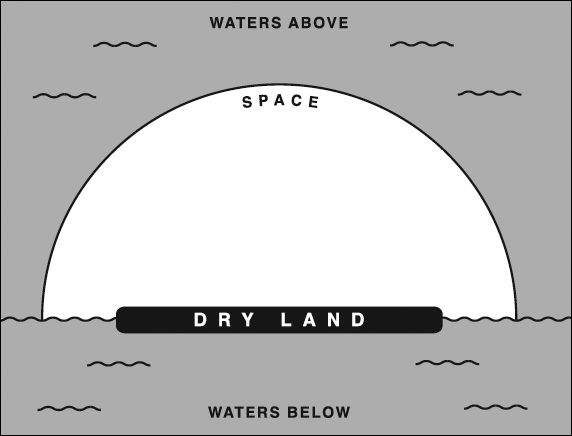

1:6. space. The distinction between “the water that was under the space and the water that was above the space” is particularly important and was frequently confusing to readers who were not certain of the meaning of the old term for this space: “firmament.” As Rashi perceived, the text pictures a territory formed in the middle of the watery chaos, a giant bubble of air surrounded on all sides by water. Once the land is created, the universe as pictured in Genesis is a habitable bubble, with land and seas at its base, surrounded by a mass of water. Like this:

God calls the space “skies.” “The skies” (or “heavens”) here refer simply to space, to the sky that we see, and not to some other, unseen place where God dwells or where people dwell after their death.

The reference to “water that was above the space” presumably reflects the fact that when the ancients looked at the sky they understood from its blue color that there was water up there above the air. As when we look out at the horizon on a clear day and can barely distinguish where the blue sea ends and the blue sky begins, so they pictured the earth as surrounded by water above and below. The space was the invisible substance that holds the upper waters back. It is important to appreciate this picture of the cosmos with which the Torah begins or one cannot understand other matters that come later, especially the story of the flood. See the comment on Gen 7:11.

1:6. Let there be a space. The “firmament” is either the entire air space or, more probably, just the transparent edge of the space, like a glass dome (Ramban says “like a tent”), which is actually up against the water. It is difficult to say which. The Hebrew root of the word, ![]() , refers to the way in which a goldsmith hammers gold leaf very thin. This may suggest that the firmament is best understood to be the thin outermost layer of the air space. Still, we must be cautious not to commit the etymological fallacy. That means: we should not automatically derive the meaning of a word from its root. People commonly make this mistake because the Hebrew of the Tanak is so beautifully constructed around three-letter roots. Looking for root meanings is usually very helpful. But sometimes it can lead to misunderstandings. Words can evolve away from their root meanings over centuries.

, refers to the way in which a goldsmith hammers gold leaf very thin. This may suggest that the firmament is best understood to be the thin outermost layer of the air space. Still, we must be cautious not to commit the etymological fallacy. That means: we should not automatically derive the meaning of a word from its root. People commonly make this mistake because the Hebrew of the Tanak is so beautifully constructed around three-letter roots. Looking for root meanings is usually very helpful. But sometimes it can lead to misunderstandings. Words can evolve away from their root meanings over centuries.

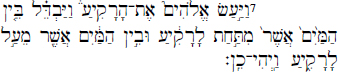

7And God made the space, and it separated between the water that was under the space and the water that was above the space. And it was so.

![]()

8And God called the space “skies.” And there was evening, and there was morning: a second day.

![]()

![]()

1:8. God called the space “skies.” The space (or “firmament”) and the sky are the same thing. This appears to be an explanation of what the sky is. It is a transparent shell or space that holds back the upper waters.

1:8. a second day. The first day’s account concludes with the cardinal number: “one day.” All of the following accounts conclude with ordinal numbers: “a second day,” “a third day,” and so on. This sets off the first day more blatantly as something special in itself rather than merely the first step in an order. It may be because the first day’s creation—light—is qualitatively different from all other things. Or it may be because the opening day involves the birth of creation itself. Or it may be that the first unit involves the creation of a day as an entity. A more mundane explanation—which is presumably the p![]() š a

š a![]() –would be that this simply is a known biblical form, which has no special meaning for the matter of creation, because it occurs elsewhere as well. See the numbering of the four rivers of Eden, which likewise uses the cardinal “one” and then the ordinals “second, third, fourth” (Gen 2:11–14; see also 2 Sam 4:2).

–would be that this simply is a known biblical form, which has no special meaning for the matter of creation, because it occurs elsewhere as well. See the numbering of the four rivers of Eden, which likewise uses the cardinal “one” and then the ordinals “second, third, fourth” (Gen 2:11–14; see also 2 Sam 4:2).

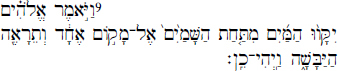

9And God said, “Let the waters be concentrated under the skies into one place, and let the land appear.” And it was so.

![]()

10And God called the land “earth,” and called the concentration of the waters “seas.” And God saw that it was good.

![]()

1:10. God saw that it was good. God observes the day’s product to be good on every day except the second day. Instead, the text says “it was good” twice on the third day. Rashi suggested that this is because the task of the division of the waters was begun on the second day but not finished until the third. But, in that case, one might still ask why the task had to be thus split between two days. The reason why the second day’s work—the formation of the space, with water above and below—is not pronounced “good” may rather be that God will later choose to break this structure (in the flood story, Gen 7:11). The double notice that “it was good” on the third day may be because (1) the formation of land and (2) the land’s generation of plants are each regarded as creations worthy of notice.

This explanation is based on the Masoretic Text (MT). The Greek text (Septuagint), on the other hand, includes the words “And God saw that it was good” on the second day as well. It may be that these words were simply omitted from the MT by a scribe whose eye jumped from the first two letters of this line (Hebrew ![]() ) to the beginning of the next line (“And there was evening …”), which begins with the same two first letters (

) to the beginning of the next line (“And there was evening …”), which begins with the same two first letters (![]() ). This is called haplography.

). This is called haplography.

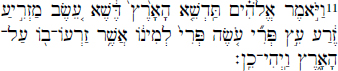

11And God said, “Let the earth generate plants, vegetation that produces seed, fruit trees, each making fruit of its own kind, which has its seed in it, on the earth. And it was so:

![]()

12The earth brought out plants, vegetation that produces seeds of its own kind, and trees that make fruit that each has seeds of its own kind in it. And God saw that it was good.

![]()

1:12. vegetation that produces seeds of its own kind. The fact that plants (and, later, animals) not only reproduce but also propagate offspring like themselves, rather than random production of new life-forms, is not taken for granted. It is treated as both fundamental and a wonder of life, which needed an explicit creative utterance by the deity.

13And there was evening, and there was morning: a third day.

![]()

![]()

1:13. third day. On the third day the divine attention turns from the cosmos to the world: first land, then the vegetation that the land yields. On the fourth day the attention turns back to the skies: the creation of lights in the sky. The alternation between skies and earth continues as the deity turns back to the earth on the fifth day. This conveys that the earth and the skies are not conceptually separate. Understanding the nature of the universe is essential to understanding our place as humans on earth. We have especially come to realize this through the discoveries in astronomy and physics of the last century.

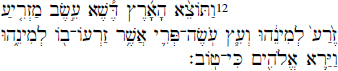

14And God said, “Let there be lights in the space of the skies to distinguish between the day and the night, and they will be for signs and for appointed times and for days and years.

![]()

15And they will be for lights in the space of the skies to shed light on the earth.” And it was so.

![]()

![]()

1:15. they will be for lights in the space. Note that daylight is not understood here to derive from the sun. The text understands the light that surrounds us in the daytime to be an independent creation of God, which has already taken place on the first day. The sun, moon, and stars are understood here to be light sources— like a lamp or torch, only stronger. Their purpose is also to be markers of time: days, years, appointed occasions.

This also implies an answer to an old question: People have questioned whether the first three days are twenty-four-hour days since the sun is not created until the fourth day. But light, day, and night are not understood here to depend on the existence of the sun, so there is no reason to think that the word “day” means anything different on the first two days than what it means everywhere else in the Torah. People’s reason for raising this is often to reconcile the biblical creation story with current evidence on the earth’s age. But it is better to recognize that the biblical story does not match the evidence than to stretch the story’s plain meaning in order to make it fit better with our current state of knowledge.

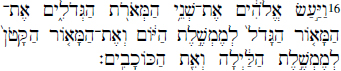

16And God made the two big lights—the bigger light for the regulation of the day and the smaller light for the regulation of the night—and the stars.

![]()

1:16. the bigger light. The sun.

1:16. the smaller light. The moon.

17And God set them in the space of the skies to shed light on the earth

![]()

![]()

18and to regulate the day and the night and to distinguish between the light and the darkness. And God saw that it was good.

![]()

![]()

19And there was evening, and there was morning: a fourth day.

![]()

![]()

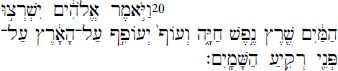

20And God said, “Let the water swarm with a swarm of living beings, and let birds fly over the earth on the face of the space of the skies.”

![]()

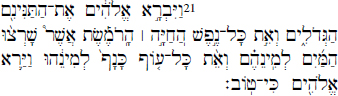

21And God created the big sea serpents and all the living beings that creep, with which the water swarmed, by their kinds, and every winged bird by its kind. And God saw that it was good.

![]()

1:21. sea serpents. Hebrew tannî n. This is generally understood to refer to some giant serpentlike creatures that were formed at creation but later destroyed, associated with the monsters Rahab (Isa 51:9) or Leviathan (Isa 27:1). Later, Aaron’s staff (and the Egyptian magicians’ staffs) turns into such a creature (not merely a snake!) at the Egyptian court (Exod 7:9–12).

22And God blessed them, saying, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the water in the seas, and let the birds multiply in the earth.”

![]()

23And there was evening and there was morning, a fifth day.

![]()

![]()

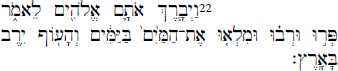

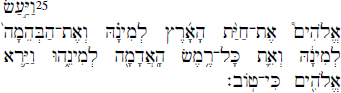

24And God said, “Let the earth bring out living beings by their kind, domestic animal and creeping thing and wild animals of the earth by their kind.” And it was so.

![]()

![]()

25And God made the wild animals of the earth by their kind and the domestic animals by their kind and every creeping thing of the ground by their kind. And God saw that it was good.

![]()

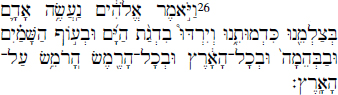

26And God said, “Let us make a human, in our image, according to our likeness, and let them dominate the fish of the sea and the birds of the skies and the domestic animals and all the earth and all the creeping things that creep on the earth.”

![]()

1:26. Let us make. Why does God speak in the plural here? Some take the plural to be “the royal we” as used by royalty and the papacy among humans, but this alone does not account for the fact that it occurs only in the opening chapters of the Torah and nowhere else. Others take the plural to mean that God is addressing a heavenly court of angels, seraphim, or other heavenly creatures, although this, too, does not explain the limitation of the phenomenon to the opening chapters. More plausible, though by no means certain, is the suggestion that it is an Israelite, monotheistic reflection of the pagan language of the divine council. In pagan myth, the chief god, when formally speaking for the council of the gods, speaks in the plural. Such language might be appropriate for the opening chapters of the Torah, thus asserting that the God of Israel has taken over this role.

27And God created the human in His image. He created it in the image of God; He created them male and female.

![]()

![]()

1:27. He. In the present age many people choose not to conceive of the deity as male or female. In the Torah, however, there are passages in which one cannot help but understand and translate a divine reference as masculine. The Torah depicts God as male. Rather than impose a present view on an ancient text, I feel bound to leave the masculine references to the deity as they are, although I urge those who study the Torah to contemplate what this has meant through the ages from the time of the writing of the Torah to their own respective times.

1:27. in the image of God. We argue but truly do not know what is meant: whether a physical, spiritual, or intellectual image of God. (Some light may be shed on this by Gen 5:3. See the comment there.) Whatever it means, though, it implies that humans are understood here to share in the divine in a way that a lion or cow does not. That is crucial to all that will follow. The paradox, inherent in the divine-human relationship, is that only humans have some element of the divine, and only humans would, by their very nature, aspire to the divine, yet God regularly communicates with them by means of commands. Although made in the image of God, they remain subordinates. In biblical terms, that would not bother a camel or a dove. It will bother humans a great deal.

1:27. in the image of God; He created them male and female. Both men and women are created in the divine image. If the physical image of God is meant, it is difficult to say what is implied about the divine appearance.

28And God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it and dominate the fish of the sea and the birds of the skies and every animal that creeps on the earth.”

![]()

1:28. Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth. This commandment has now been fulfilled.

1:28. subdue it and dominate. Incredibly, some have interpreted this command to mean that humans have permission to abuse the earth and animal and plant life—as if a command from God to rule did not imply to be a good ruler!

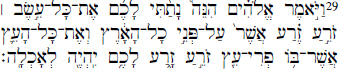

29And God said, “Here, I have placed all the vegetation that produces seed that is on the face of all the earth for you and every tree, which has in it the fruit of a tree producing seed. It will be food for you

![]()

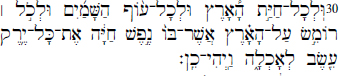

30and for all the wild animals of the earth and for all the birds of the skies and for all the creeping things on the earth, everything in which there is a living being: every plant of vegetation, for food.” And it was so.

![]()

31And God saw everything that He had made, and, here, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day.

![]()

1:31. everything that He had made, and, here, it was very good. The initial state of creation is regarded as satisfactory. Things will soon go wrong, but it is unclear if that means that the “good” initial state becomes flawed, or if there is hope that the course of events will fit into an ultimately good structure in “the length of days.” One of the most remarkable results of having a sense of the Tanak as a whole when one reads the parts is that one can experience the overwhelming irony of God’s judging everything to be good in Genesis 1 when so much will go wrong later. The deity notes on every working day that what was created in that day is good (except on Monday, but it compensates, saying “God saw that it was good” twice on Tuesday; see the comment on 1:10,12). And at the end of the six days God observes that everything is very good. But before we are even out of Parashat Bereshit we read that God begins to see “that human bad was multiplied in the earth” (6:5). Above all, the struggle between God and humans will recur and unfold powerfully and painfully. The day in which the humans are created is declared to be good, but this condition ends very soon. No biblical hero or heroine will be unequivocally perfect. Individuals and nations, Israel and all of humankind, will be pictured in conflict with the creator for the great majority of the text that will follow. Parashat Bereshit is a portent of this coming story, which is arguably the central story of the Tanak, because its first chapter contains the creation of humans that is divinely dubbed good, and its last verses contain the sad report that God regrets making the humans in the earth (6:6ff.). Importantly Parashat Bereshit ends not with the deity’s mournful statement that “I regret that I made them” (6:7) but rather with a point of hope: that Noah found favor in the divine sight (6:8). And this note, that there can be hope for humankind based on the acts of righteous individuals, is also a portent of the end of the story. In the last installment in the narrative, the book of Nehemiah, God does not speak, there are no extraordinary reports of miracles, no angels, dreams, talking animals, or Urim and Tummim (see comment on Exod 28:30); but humans, now having to live without these things, behave better and appear to be more committed to the Torah than perhaps any other generation in the Bible. (Nehemiah comes last in the Leningrad Codex, the oldest complete manuscript of the entire Tanak. Printed editions of the Hebrew Bible generally have the books of Chronicles last, but the story ends with Nehemiah.) Nehemiah ends by asking his God to “Remember me for good” (13:31). The fact that the Hebrew Bible’s story concludes with the word “good” is an exquisite, hopeful bookend to the opening chapter of Genesis, in which everything starts out being good.