1And it was after these things, and God tested Abraham.

And He said to him, “Abraham.”

And he said, “I’m here.”

![]()

![]()

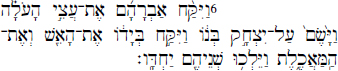

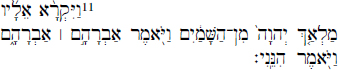

22:1. He said to him, “Abraham.” The Greek and Samaritan versions have his name called twice here: “Abraham, Abraham.” This parallels the call by the angel later (v. 11), by which Abraham is stopped from sacrificing Isaac. Thus the instruction to sacrifice him and the instruction to hold back are given equal weight. This also parallels the repetition of Moses’ name in God’s first words to him at the burning bush (Exod 3:4) and the repetition of Samuel’s name the first time God speaks to him (1 Sam 3:10). This appears to be a mark of divine communication at significant moments in the biblical narrative. What stands out about Abraham is that it comes here in the Aqedah rather than the first time that God speaks to him. This marks the near-sacrifice as a defining event in Abraham’s life and in the destiny of his descendants.

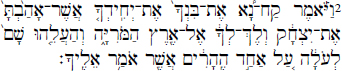

2And He said, “Take your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac, and go to the land of Mo-riah and make him a burnt offering there on one of the mountains that I’ll say to you.”

![]()

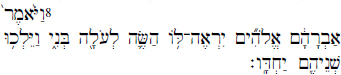

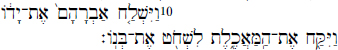

22:2. Take your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac. If the issue were only a matter of identification, just the name Isaac would have been sufficient; but the issue, we are told explicitly in the first verse of the story, is the test. The fourfold, heartrending identification creates background for all that is to come. Now Abraham’s unquestioning obedience is understood against this background: “your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac.” The otherwise minor temporal note that “Abraham got up early in the morning” to do the deed becomes a fact worthy of wonder and interpretation against the background of “your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac.” The notation that he puts the wood for the sacrificial fire on Isaac himself to carry becomes an ironic image. Abraham’s words to the servants who accompany them—”I and the boy: we’ll go over there, and we’ll bow, and we’ll come back to you”—become not only enigmatic but emotionally charged. (Does his saying “we’ll come back” suggest extraordinary faith? one last hope? Or is it constructed so as not to frighten Isaac?) The words of the dialogue between the father and son become charged by this background as well, as Isaac adds the phrase “my father” in his question addressed to Abraham, and Abraham adds “my son” in each sentence in response. (The words “son” and “father” occur twelve times in the story and are, in almost every case, unnecessary for identification.) The dialogue moreover begins and ends with the words “and the two of them went together,” another mundane phrase turned into a remarkable one by what has preceded.

Most remarkable of all is the exchange between Abraham and Isaac over the obvious absence of an animal to be sacrificed. Isaac says, “Here are the fire and the wood, but where is the sheep for the burnt offering?” To appreciate the artistry of the wording of Abraham’s answer, we must keep in mind that the Hebrew has no punctuation. The text says: “God will see to the sheep for the burnt offering my son”—which can be understood in two ways. The last two words can be read as a touching epithet:

“God will see to the sheep for the burnt offering, my son.”

But they can also be read as a fearful irony:

“God will see to the sheep for the burnt offering: My son.”

—subtly conveying the truth that Isaac himself is to be the sheep for the sacrifice.

And so the short passage, which like the entire chapter expresses no emotions explicitly, reads like a tightly packed container whose contents may burst in a moment:

And the two of them went together.

And Isaac said to Abraham his father; he said, “My father.”

And he said, “I’m here, my son.”

And he said, “Here are the fire and the wood, but where is the sheep for the burnt offering?”

And Abraham said, “God will see to the sheep for the burnt offering my son.” And the two of them went together.

The denouement of the story, in which Isaac is spared, is no less charged by all of this expressed and unexpressed background. Indeed, Abraham’s feelings (relief? gratitude? reverence? confusion?) are likewise not a part of the narrative. There is rather a reminiscence of the original wording, as God twice says to Abraham that now all is well because “You didn’t hold back your son, your only one” (22:12,16; cf. 22:2). As biblical interpreters noted centuries ago, the wording suggests that the reward at the end is in proportion to the difficulty of the test as expressed at the beginning.

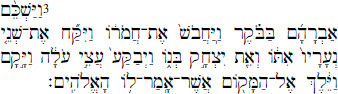

3And Abraham got up early in the morning and harnessed his ass and took his two boys with him and Isaac, his son. And he cut the wood for the burnt offering, and he got up and went to the place that God had said to him.

![]()

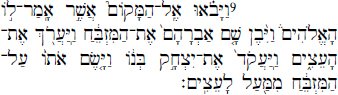

22:3. Abraham got up early in the morning. Abraham fights for the lives of the people of Sodom and Gomorrah but not for the life of Isaac. That is a strange fact itself, and then these two stories are juxtaposed by being placed in the same parashah so that they are regularly read together, which makes the ironic relationship between them even harder to ignore. When God tells Abraham, “The cry of Sodom and Gomorrah: how great it is. And their sin: how very heavy it is. Let me go down, and I’ll see if they’ve done, all told, like the cry that has come to me. And if not, let me know” (18:20–21), Abraham’s response is to be the first human in the Bible’s story to challenge a divine decision. But when God tells him, “Take your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac … and offer him as a burnt offering,” the report is: And Abraham got up early in the morning!

The text does not tell us what Abraham’s motive is for questioning his God about the fate of Sodom. Is it because his nephew, Lot, lives there? Or is it Abraham’s sense of justice? Or is it his compassion for people who are facing a divine catastrophe? Two of the above? All of the above? Even if it is mainly his concern for Lot, still, that’s a nephew. Isaac is his son! Even if it is his compassion for those morally-challenged people of Sodom, still, there must also be compassion for his son. And if it is his sense of justice, is there less of a case for justice in connection with sacrificing an innocent Isaac than in the matter of the destruction of those very guilty people?

One possible answer: The mark of Abraham’s personality is obedience. He will obey anything that his God commands him to do. Leave your land. Leave your birthplace. Leave your father’s house. Circumcise yourself. Even if he is commanded to sacrifice his child, he will do it. There are no arguments or even questions. There is only immediate compliance. But the case of Sodom and Gomorrah is different because in this case Abraham is not commanded to do anything. He is not the one who is to execute judgment on the cities. It is even intriguing that the deity chooses to inform Abraham of the divine concern over the cries from Sodom and Gomorrah in the first place. Whatever reason one imagines for God to tell Abraham about this, the fact is that by informing Abraham of the divine intention to look into the situation in Sodom and Gomorrah, God opens the door for Abraham to speak up. Commands, on the other hand, leave no room for discussion.

A second answer (d![]() bar ’a

bar ’a![]()

![]() r): The reason that Abraham speaks up for the more distant relative and for all the unrelated populace of Sodom and Gomorrah but does not speak up for his own son is precisely because it is his own son. He is sufficiently distant from Lot and the populace of Sodom that he is in a position to argue whether their destruction would be just. And so he argues: “Will the judge of all the earth not do justice?!” But in the case of Isaac, he is not what we would call an unbiased observer. He has a personal interest in the case, an intensely personal interest. And, as such, he does not have the same standing to argue the justice or injustice of the case.

r): The reason that Abraham speaks up for the more distant relative and for all the unrelated populace of Sodom and Gomorrah but does not speak up for his own son is precisely because it is his own son. He is sufficiently distant from Lot and the populace of Sodom that he is in a position to argue whether their destruction would be just. And so he argues: “Will the judge of all the earth not do justice?!” But in the case of Isaac, he is not what we would call an unbiased observer. He has a personal interest in the case, an intensely personal interest. And, as such, he does not have the same standing to argue the justice or injustice of the case.

A third answer (d![]() bar ‘ah

bar ‘ah![]() r): Another possible explanation is that the outcome of the Sodom and Gomorrah matter itself is what causes Abraham to stay silent in the matter of Isaac. In the famous dialogue between God and Abraham over the fate of the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, the exchange is subtle as God responds not merely to what Abraham says but apparently to what is in Abraham’s heart. Thus: when Abraham learns that God means to judge these cities, he says, “Maybe there are fifty virtuous people within the city” (18:24). God responds, “If I find in Sodom fifty virtuous people within the city, then I’ll sustain the whole place for their sake” (18:26). Abraham’s next bargaining position will be the sparing of the place for forty-five righteous, but he articulates his question in such a way as to make it seem a small request. He does not say “forty-five.” He says:

r): Another possible explanation is that the outcome of the Sodom and Gomorrah matter itself is what causes Abraham to stay silent in the matter of Isaac. In the famous dialogue between God and Abraham over the fate of the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, the exchange is subtle as God responds not merely to what Abraham says but apparently to what is in Abraham’s heart. Thus: when Abraham learns that God means to judge these cities, he says, “Maybe there are fifty virtuous people within the city” (18:24). God responds, “If I find in Sodom fifty virtuous people within the city, then I’ll sustain the whole place for their sake” (18:26). Abraham’s next bargaining position will be the sparing of the place for forty-five righteous, but he articulates his question in such a way as to make it seem a small request. He does not say “forty-five.” He says:

Maybe the fifty virtuous people will be short by five.

Will you destroy the whole city for the five?

To which God replies, “I won’t destroy if I find forty-five there.” Thus God would appear to be conveying to Abraham that there is not much point to being cagey in one’s words when one is arguing with someone who is omniscient. After this, Abraham words his positions more straightforwardly: What if there are forty? thirty? etc. Abraham gets the message that he may as well say directly what is on his mind because that is what is going to be responded to in any case.

Even then, Abraham succeeds in getting down to ten. God agrees to sustain the cities for ten virtuous people. But not even ten are to be found, and the cities are destroyed. So even though Abraham’s dialogue with God is important in several ways—including: it provides Abraham with an opportunity to articulate the principle of justice for future generations; and it is an important step in the growth of humankind’s independence and development of responsibility—the fact remains that nothing is changed for Sodom and Gomorrah by this. Abraham learns that, since God knows what is in one’s heart, why argue? Since God knows the situation and its necessary outcome, why speak? After the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Abraham never argues with God again. Moses will argue with God, Jonah will, Jeremiah will, but not Abraham. When the creator tells Abraham to listen to Sarah and send Hagar and Ishmael away, “Abraham got up early in the morning” (21:14). When the creator tells him to sacrifice his son, “Abraham got up early in the morning” (22:3).

But Abraham’s obedience is what saves Isaac in the end. What an irony: Abraham’s silence over Isaac is more effective than his argument over Sodom and Gomorrah.

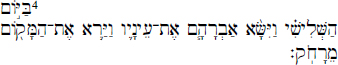

4On the third day: and Abraham raised his eyes and saw the place from a distance.

![]()

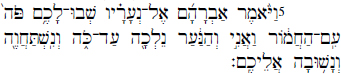

5And Abraham said to his boys, “Sit here with the ass; and I and the boy: we’ll go over there, and we’ll bow, and we’ll come back to you.”

![]()

6And Abraham took the wood for the burnt offering and put it on Isaac, his son, and took the fire and the knife in his hand.

And the two of them went together.

![]()

7And Isaac said to Abraham, his father; and he said, “My father.”

And he said, “I’m here, my son.”

And he said, “Here are the fire and the wood, but where is the sheep for the burnt offering?”

![]()

8And Abraham said, “God will see to the sheep for the burnt offering, my son.”

And the two of them went together.

![]()

9And they came to the place that God had said to him. And Abraham built the altar there and arranged the wood, and he bound Isaac, his son, and put him on the altar on top of the wood.

![]()

10And Abraham put out his hand and took the knife to slaughter his son.

![]()

11And an angel of YHWH called to him from the skies and said, “Abraham! Abraham!”

And he said, “I’m here.”

![]()

12And he said, “Don’t put your hand out toward the boy, and don’t do anything to him, because now I know that you fear God, and you didn’t withhold your son, your only one, from me.”

![]()

13And Abraham raised his eyes and saw, and here was a ram behind, caught in the thicket by its horns. And Abraham went and took the ram and made it a burnt offering instead of his son.

![]()

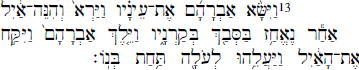

22:13. behind. Some manuscripts read “one” ram, i.e., Hebrew ![]() , rather than “behind,” Hebrew

, rather than “behind,” Hebrew ![]() . “One” makes plainer sense, but this may very well be a case that suggests the principle of lectio difficilior praeferenda est (the more difficult reading is preferable). That is, scribes tend to simplify an unusual reading more often than they make a change that turns a simple reading into a more difficult one. The matter remains unsolved.

. “One” makes plainer sense, but this may very well be a case that suggests the principle of lectio difficilior praeferenda est (the more difficult reading is preferable). That is, scribes tend to simplify an unusual reading more often than they make a change that turns a simple reading into a more difficult one. The matter remains unsolved.

14And Abraham called the name of that place “YHWH Yir’eh,” as is said today: “In YHWH’s mountain it will be seen.”

![]()

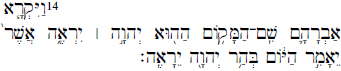

22:14. YHWH Yir’eh. Meaning “YHWH Will See.” (Perhaps it should be pointed as YHWH Yera’eh, “YHWH Will Appear”—which is how it appears later in the same verse.)

15And an angel of YHWH called to Abraham a second time from the skies

![]()

![]()

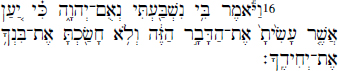

16and said, “I swear by me—word of YHWH—that because you did this thing and didn’t withhold your son, your only one,

![]()

17that I’ll bless you and multiply your seed like the stars of the skies and like the sand that’s on the seashore, and your seed will possess its enemies’ gate.

![]()

18And all the nations of the earth will be blessed through your seed because you listened to my voice.”

![]()

![]()

22:18. all the nations of the earth will be blessed through your seed. This is the third occurrence of this promise. (See the comment on Gen 12:3.)

19And Abraham went back to his boys, and they got up and went together to Beer-sheba, and Abraham lived in Beer-sheba.

![]()

![]()

22:19. Abraham went back to his boys. The text does not mention Isaac going back. (And Abraham had specifically told the boys, “We’ ll come back to you.”) Both midrash and critical scholarship have dared to raise the possibility that in one version of the story Abraham actually sacrifices Isaac (discussed in Who Wrote the Bible? p. 257). But in the present form of the text itself, Isaac clearly is spared. And that makes this verse extraordinarily powerful. Following the Aqedah, Isaac and Abraham do not go back together. Moreover: following the Aqedah, Isaac and Abraham are never quoted as speaking to each other.

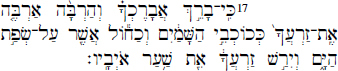

20And it was after these things, and it was told to Abraham, saying, “Here Milcah has given birth, she also, to sons for your brother Nahor:

![]()

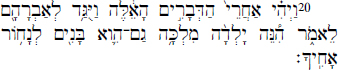

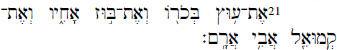

21Uz, his firstborn, and Buz his brother, and Kemuel, the father of Aram,

![]()

22and Chesed and Hazo and Pildash and Jidlaph and Bethuel.

![]()

![]()

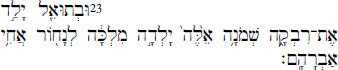

23And Bethuel fathered Rebekah.” Milcah gave birth to these eight for Nahor, Abraham’s brother.

![]()

24And his concubine, whose name was Reumah, she too gave birth, to Tebah and Gaham and Tahash and Maacah.

![]()

![]()