1And YHWH spoke to Moses and to Aaron, saying to them,

![]()

![]()

11:1. YHWH spoke to Moses and to Aaron, saying. This is only the second report of laws being addressed to Aaron along with Moses. The first law given to the people, the Passover command, is pronounced to both Moses and Aaron (Exod 12:1), but then the laws are stated only to Moses. Indeed, the only other time that YHWH has spoken to both Moses and Aaron until now was at the beginning of their mission in Egypt (and there the text does not report the words that God says to them). The inclusion of Aaron at this point may be more of the divine response to Aaron’s loss of his sons (see comment on 10:8). Or it may be because God has just told Aaron that he and his sons are to instruct the people and distinguish between holy and secular and between impure and clean (10:10–11), and so now God begins to inform Aaron of the laws that he needs to know.

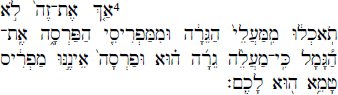

2“Speak to the children of Israel, saying: This is the animal that you shall eat out of all the domestic animals that are on the earth:

![]()

![]()

11:2. This is the animal that you shall eat. The laws of permitted and forbidden animals add further restrictions to the sacrificial laws. God requires not only ritual slaughter, priestly performance, and location at the Tent of Meeting; God delineates to Moses and Aaron which animals may be eaten as well. Among land animals: those that have split hooves and chew their cud. In water: those with scales and fins. (Redundant? All scaled fish have fins.) In the air: the forbidden birds are named one by one, and all flying creatures that have four legs are forbidden. Also forbidden are creatures that have numerous legs, those that crawl on their bellies, and any animals at all that have died on their own or that have been killed by other animals. The reasons for these particular inclusions and exclusions have never been worked out persuasively. Explanations based on health and hygiene are difficult to defend, both because the text never states this and because such explanations cannot be consistently applied to the cases. Popular claims about the unhealthy habits of pigs, for example, apply equally to various fowl that are permitted. Some suggest that the Israelites may have observed empirically that people who ate pork suffered more illness than others, but this is without any textual or historical evidence; nor does it explain how this fact was apparent to Israelites but unobserved by the rest of the world for thousands of years. Popular claims that the forbidden animals were objects of worship are simply wrong. Suggestions that the system is ultimately about matters of ethics and not food—that is, that it teaches discipline, self-denial, and so on—are not supported in the text. The text rather relates various food laws to issues of impurity (see below) and “abomination,” which fall in the realm of ritual, not ethical, categories. Observance of ritual laws may have an ethical dimension, such as discipline, but this may be said of all ritual laws. It sheds no special light on this particular group of commandments.

The anthropologist Mary Douglas has suggested what is perhaps the most-cited treatment at present (Purity and Danger), which she and I have discussed: that the issue is one of defined classes of animals: Split-hoofed, cud-chewing animals are “the model of the proper kind of food for a pastoralist” (p. 54), and so this became the model of what was appropriate to eat. Wild goats and antelope share these two characteristics and therefore were acceptable. Pigs, which have a split hoof but do not chew their cud, were excluded originally for the sole reason that they did not fit this class as defined. Similarly with the forbidden water creatures: they did not fit the class that had the “right” kind of locomotion, namely fins and scales. Similarly with animals that have two hands and two legs (weasels, mice, lizards) but walk on all fours like a quadruped: they “perversely” use hands for walking. Not having the right form of locomotion, they are forbidden.

Douglas’s explanation appears to me to be a self-defining system. Whatever is permitted she identifies as what the Israelites perceived to be “right.” Whatever is forbidden, she concludes, came to be forbidden because it did not fit the category. This is mere definitional description unless it can shed some light on the underlying reasons for these perceptions of what was proper. Where Douglas tries to identify the reasons she errs, in my judgment. The assertion that the split hoof and the chewing of cud were “the model of the proper kind of food for a pastoralist” is unhelpful without proof that Israel was in fact primarily a pastoral society. It was not. (And Leviticus 11 certainly does not appear to come from a pastoral circle. It comes from an urban priesthood.) Nor does this explain why the non-Israelite residents of the land, who alternately (and sometimes simultaneously) lived on the same sites, conceived of these same animals so differently. Excavations uncover pig bones in a Canaanite layer of a site, then no pig bones in an Israelite layer of the same site, then pig bones again in the site’s next Canaanite layer. There is likewise no reason to associate the presence of scales on a fish with a concept of a proper form of locomotion. And Douglas’s notion of a “perverse” form of locomotion by animals whose front limbs are handlike is simply a misunderstanding of the Hebrew term (kap), which does not mean “hand.” It refers elsewhere to both the hands and the feet (Gen 8:9; Deut 2:5; 11:24; 28:35,56; Josh 1:3; 2 Sam 14:25) and is correctly translated “paws” (a translation that Douglas appears to eschew). In its context here it follows a verse that refers to the matter of split hooves (11:26), and it is simply forbidding all animals that have soft paws rather than hooves. Douglas’s treatment may add some helpful perspectives to the discussion, but the essential mystery remains unsolved.

I have tried here to exclude some of the common explanations that appear to me to be looking in the wrong directions, and I mean to identify some elements that should be taken into account. The first is: similarity to humans. The fact that the text elsewhere has conceived of animals, but not plants, as having the quality of life (nepeš) in common with humans, even though plants do in fact live and die, already means that the degree of similarity to humans figured in the distinctions, whether consciously or not. Plants were so different from humans as not to be thought of as a life-form in the same sense and therefore not even considered as having to be permitted or forbidden. In the animal kingdom, meanwhile, on a continuum of likeness to humans, at one extreme would be cannibalism, which is so extreme as not even to be considered (unless the law against human sacrifice is understood necessarily to prevent it). Next would be the ape family, which is forbidden, having soft hands and feet; then all fellow creatures having soft hands and feet or paws (kap) like humans rather than hooves. Next might be all animals that, like humans, are carnivorous (thus including numerous land animals, all birds of prey, and various reptiles). The permissible animals would then be those that are twice-distinguished from humans, both having a split hoof and chewing their cud. Animals that have only one of these are especially singled out by species, such as pigs (which have a split hoof but do not chew the cud) and camels (which chew the cud but do not have a split hoof). This does not explain all of the permissions and prohibitions of Leviticus 11. Notably, it does not account for water creatures (few creatures are as unlike humans as lobsters) or insects (why are locusts permitted?). It does, however, relate to enough of the distinctions that it should be taken into account in any attempt to explain this list. Ultimately, since no single underlying principle has been discovered that accounts for all the distinctions, it appears likely that there is a convergence of two or probably more factors. It could be a combination of a principle (such as likeness to humans) and completely idiosyncratic factors (a distaste, phobia, or even allergy on the part of some individual in an authoritative position).

For the larger purpose of coming to an understanding of Leviticus, it is important for now to note the fact of distinction and how seriously and pervasively it is developed here in regard to a basic function of life. The list confirms this explicitly by concluding:

This is the instruction [tôr![]() h] for animal and bird and every living being that moves in the water and for every being that swarms on the earth, to distinguish[l

h] for animal and bird and every living being that moves in the water and for every being that swarms on the earth, to distinguish[l![]() habdîl] between the impure and the pure, and between the living thing that is eaten and the living thing that shall not be eaten. (11:46–47)

habdîl] between the impure and the pure, and between the living thing that is eaten and the living thing that shall not be eaten. (11:46–47)

3every one that has a hoof and that has a split of hooves, that regurgitates cud among animals, you shall eat it.

![]()

![]()

11:3. a split of hooves. Each of its hooves is split, e.g., cows; as opposed to those that have a single hoof, e.g., horses.

4Except you shall not eat this out of those that regurgitate the cud and out of those that have a hoof: The camel, because it regurgitates cud and does not have a hoof; it is impure to you.

![]()

5And the rock-badger, because it regurgitates cud and does not have a hoof; it is impure to you.

![]()

![]()

6And the hare, because it regurgitates cud and does not have a hoof; it is impure to you.

![]()

11:6. the hare, because it regurgitates cud. Hares do not regurgitate cud.

7And the pig, because it has a hoof and has a split of hooves, and it does not chew cud; it is impure to you.

![]()

8You shall not eat from their meat, and you shall not touch their carcass. They are impure to you.

![]()

![]()

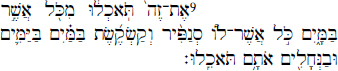

9“You shall eat this out of all that are in the water: every one that has fins and scales in the water—in the seas and in the streams—you shall eat them.

![]()

11:9. all that are in the water. There is no differentiation of species of water creatures in the entire Tanak. All fish are simply called d![]() g. My colleague Jacob Milgrom has proposed that the reason for this is that ancient Israelites knew little of fish because the eastern Mediterranean was not suitable for fish until the opening of the Suez Canal in our era, which changed the ecology of that sea. But even if this were so—that there were no fish in the eastern Mediterranean—the Israelites still had the Red Sea, the Sea of Galilee, and the Jordan River. Surely those who lived near these bodies of water knew one fish from another. A more likely explanation is that the list of permitted and forbidden animals came from the Jerusalem priesthood, and before the invention of refrigeration it would have been extremely rare for anyone in Jerusalem to have an opportunity to eat fish.

g. My colleague Jacob Milgrom has proposed that the reason for this is that ancient Israelites knew little of fish because the eastern Mediterranean was not suitable for fish until the opening of the Suez Canal in our era, which changed the ecology of that sea. But even if this were so—that there were no fish in the eastern Mediterranean—the Israelites still had the Red Sea, the Sea of Galilee, and the Jordan River. Surely those who lived near these bodies of water knew one fish from another. A more likely explanation is that the list of permitted and forbidden animals came from the Jerusalem priesthood, and before the invention of refrigeration it would have been extremely rare for anyone in Jerusalem to have an opportunity to eat fish.

10And any one that does not have fins and scales in the seas and in the streams—out of every swarming thing of the water and out of every living being that is in the water—they are a detestable thing to you,

![]()

11and they shall be a detestable thing to you. You shall not eat from their meat, and you shall detest their carcass.

![]()

12Every one that does not have scales and fins in the water, it is a detestable thing to you.

![]()

![]()

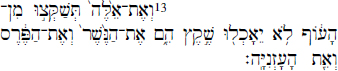

13“And you shall detest these out of the flying creatures. They shall not be eaten. They are a detestable thing: the eagle and the vulture and the black vulture

![]()

14and the kite and the falcon by its kind,

![]()

![]()

15every raven by its kind

![]()

![]()

16and the eagle owl and the nighthawk and the seagull and the hawk by its kind

![]()

![]()

11:16. eagle owl. Hebrew bat hayya’![]() n

n![]() h. It has usually been identified as an ostrich. Milgrom has thrown that identification into doubt. I agree. Moreover, ostriches are primarily plant-eating, like the permitted birds. Therefore: the ostrich is not necessarily forbidden for food.

h. It has usually been identified as an ostrich. Milgrom has thrown that identification into doubt. I agree. Moreover, ostriches are primarily plant-eating, like the permitted birds. Therefore: the ostrich is not necessarily forbidden for food.

17and the little owl and the cormorant and the great owl

![]()

![]()

18and the white owl and the pelican and the fish hawk

![]()

![]()

19and the stork and the heron by its kind and the hoopoe and the bat.

![]()

![]()

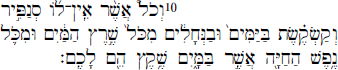

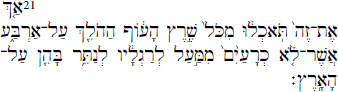

20Every swarming thing of flying creatures that goes on four—it is a detestable thing to you.

![]()

![]()

21Except you shall eat this out of every swarming thing of flying creatures that goes on four: that which has jointed legs above its feet, to leap by them on the earth.

![]()

![]()

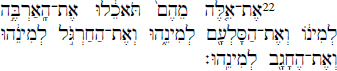

22You shall eat these out of them: the locust by its kind and the bald locust by its kind and the cricket by its kind and the grasshopper by its kind.

![]()

23And every swarming thing of flying creatures that has four legs—it is a detestable thing to you.

![]()

![]()

24“And you will become impure by these—everyone who touches their carcass will be impure until evening,

![]()

![]()

25and everyone who carries their carcass shall wash his clothes and be impure until evening—

![]()

![]()

26by every animal that has a hoof and does not have a split of hooves and does not regurgitate its cud. They are impure to you. Everyone who touches them will be impure.

![]()

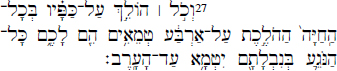

27And every one that goes on its paws among all the animals that go on four, they are impure to you. Everyone who touches their carcass will be impure until evening,

![]()

28and one who carries their carcass shall wash his clothes and be impure until evening. They are impure to you.

![]()

29“And this is the impure to you among the things that swarm on the earth: the rat, the mouse, and the great lizard by its kind

![]()

![]()

30and the gecko and the spotted lizard and the lizard and the sand lizard and the chameleon.

![]()

![]()

11:30. spotted lizard. The identification of several of the animals on this list is uncertain. Milgrom favors the spotted lizard for this one.

31These are the impure to you among all the swarming things. Everyone who touches them when they are dead will be impure until evening.

![]()

![]()

32And everything on which one of them will fall when they are dead will be impure, out of every wooden item or clothing or leather or sack, every item with which work may be done shall be put in water and will be impure until evening and then will be pure.

![]()

33And every clay container into which any of them will fall: everything that is inside it will be impure, and you shall break it.

![]()

34Every food that may be eaten on which water will come will be impure, and every liquid that may be drunk in any container will be impure.

![]()

35And everything on which some of their carcass will fall will be impure. An oven or stove shall be demolished. They are impure, and they shall be impure to you.

![]()

36Except a spring or a cistern with a concentration of waters will be pure. And one who touches their carcass will be impure.

![]()

![]()

37And if some of their carcass will fall on any sowing seed that will be sown, it is pure.

![]()

![]()

38And if water will be put on a seed, and some of their carcass will fall on it, it is impure to you.

![]()

![]()

39“And if any of the animals that are yours for food will die, the one who touches its carcass will be impure until evening,

![]()

![]()

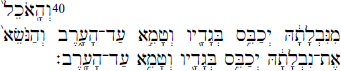

40and the one who eats some of its carcass shall wash his clothes and is impure until evening, and the one who carries its carcass shall wash his clothes and is impure until evening.

![]()

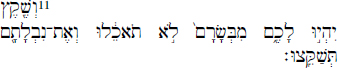

41“And every swarming creature that swarms on the earth, it is a detestable thing. It shall not be eaten.

![]()

![]()

42Everything going on a belly and everything going on four as well as everything having a great number of legs of every swarming creature that swarms on the earth: you shall not eat them because they are a detestable thing.

![]()

11:42. belly. The third letter of this word in the Hebrew text is written extra large, thus: ![]() —and it is the middle of the Torah in terms of letters.

—and it is the middle of the Torah in terms of letters.

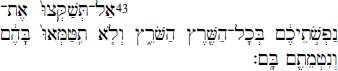

43Do not make yourselves detestable with any swarming creature that swarms, and you shall not become impure with them, so that you will be impure through them.

![]()

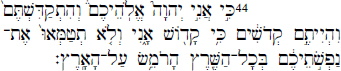

44Because I am YHWH, your God, and you shall make yourselves holy, and you shall be holy because I am holy. And you shall not make yourselves impure with any swarming creature that creeps on the earth.

![]()

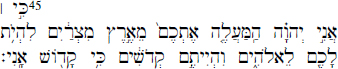

45Because I am YHWH, who brought you up from the land of Egypt to be God to you, and you shall be holy because I am holy.

![]()

46“This is the instruction for animal and bird and every living being that moves in the water and for every being that swarms on the earth,

![]()

![]()

47to distinguish between the impure and the pure, and between the living thing that is eaten and the living thing that shall not be eaten.”

![]()

![]()