From the 1890s to the start of Neville’s Aviation Career

Naval Service

On 14 April 1897, Neville came fourth in the competitive exam held by the Civil Service Commission in London for entry as a cadet in the Royal Navy. He scored well in Arithmetic, Algebra, Geometry, English, French, Scripture, Latin, English History and Geography, gaining 1614 marks out of a possible 2150. His lowest marks were in handwriting.

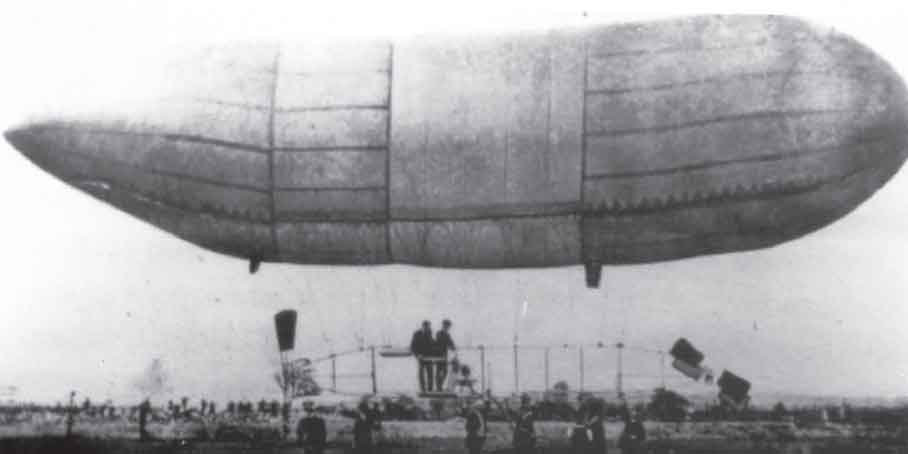

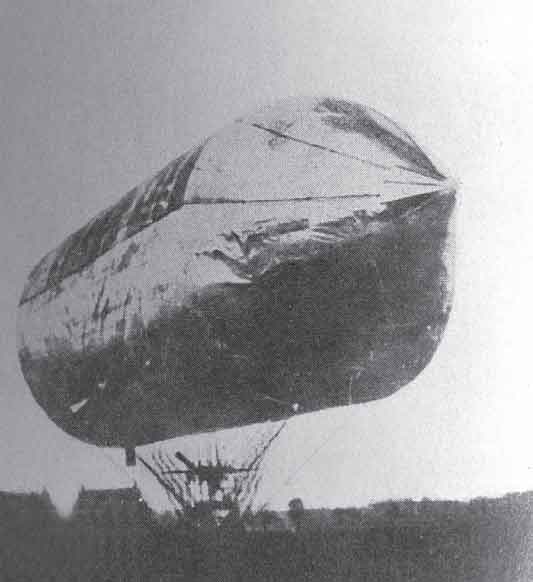

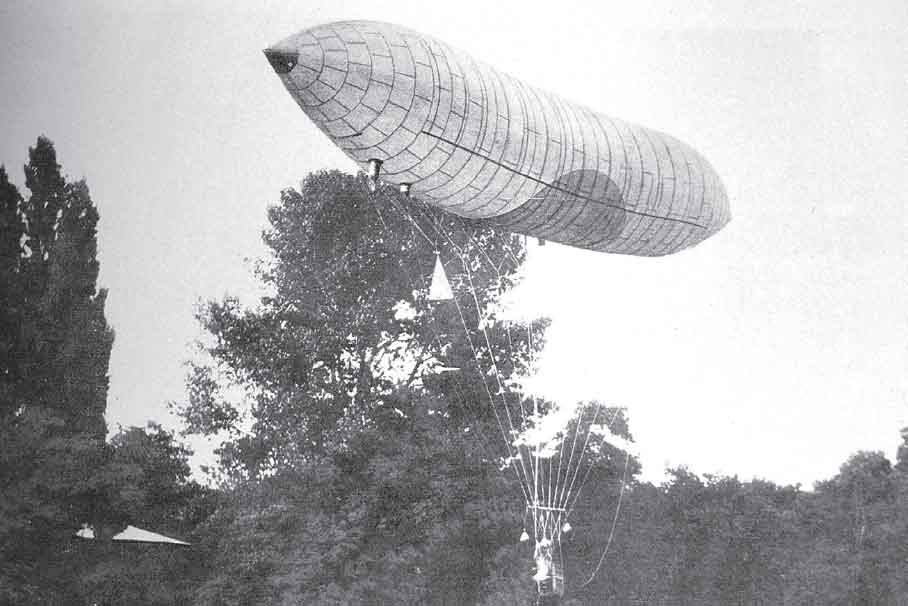

The previous year, on 28 August 1896, the first petrol-driven dirigible (an airship that could be steered as opposed to a balloon which travelled where the wind took it), powered by a 2 hp (1.48 kW) engine, had undertaken its maiden flight, Dr Karl Wöelfert’s Deutschland in Berlin. This was an important moment in aviation history – an aircraft had flown which could not only be steered, but had a power unit light enough to be carried aloft with ease and with development potential. Sadly, on 4 June 1897, Wöelfert, who was born in 1852, and his mechanic, Knabe, were killed in an accident on the Deutschland, when the engine vaporiser set fire to the envelope, causing an explosion of the gas within; so becoming the first dirigible fatalities. Also in 1897, the Hungarian engineer, David Schwarz (1852–1897), built a rigid dirigible with both frame and envelope constructed entirely from sheet aluminium only 0.008 inches (0.02 millimetres) in thickness – the Metallballon. It was 156 feet (47 metres) in length and its volume was 130,500 cubic feet (3693 cubic metres). It was powered by a Daimler 12 hp (8.88 kW) engine driving three propellers. In appearance it resembled a fat pencil stub. It took off on 3 November for its maiden flight from Tempelhof in Berlin and circled several times, but descended rapidly and broke up, fortunately without injury to the crew. The following year, 1898, the first pilot to be shot down by enemy forces was Sergeant William Ivy of the US Signal Corps Balloon Section. He was flying in Cuba during the Spanish-American War and, while observing the Spanish positions on San Juan Hill, he came under fire. The balloon’s envelope was holed and splashed into the water, fortunately for the aeronaut; he lived to tell the tale and to fly another day. [Author’s note: It was not until 1 August 1907 that the Aeronautical Division of the US Army Signal Corps was formed, the first dirigible being No 1, which took to the air for its maiden flight on 4 August 1908.]

Wöelfert’s Deutschland at Templehof in 1896.

Schwartz’s dirigible at Templehof in 1897.

The Royal Navy, in the last decade of the nineteenth century, had undergone immense technological changes in the previous fifty years – the transition from sail to steam propulsion; the change from solid iron cannon balls to shells filled with high explosive; the development of rifled and breech-loaded guns; the change in position of the location of the main armament from batteries mounted inside the hull to turrets mounted on the upper deck, with the consequent greatly increased arc of fire; the introduction of armour plate to protect ships’ hulls, and the most vital and vulnerable machinery contained therein; the replacement of wood in the construction of ships by iron and steel; and, as previously noted, the invention of the torpedo and small vessels to launch these, which could pose a formidable threat to the largest battleship; the introduction of torpedo boat destroyers as a countermeasure; armoured cruisers for the protection of commerce around the world; lighter cruisers as scouts, and the development of homogeneous classes of warships which could operate tactically as a fleet. Soon to come were the sea mine, the submarine and aviation. To match all of the above, tactical doctrine and the training of officers also needed modernisation, which did not always find favour with senior officers who still hankered after the age of sail.

Naval Training in HMS Britannia

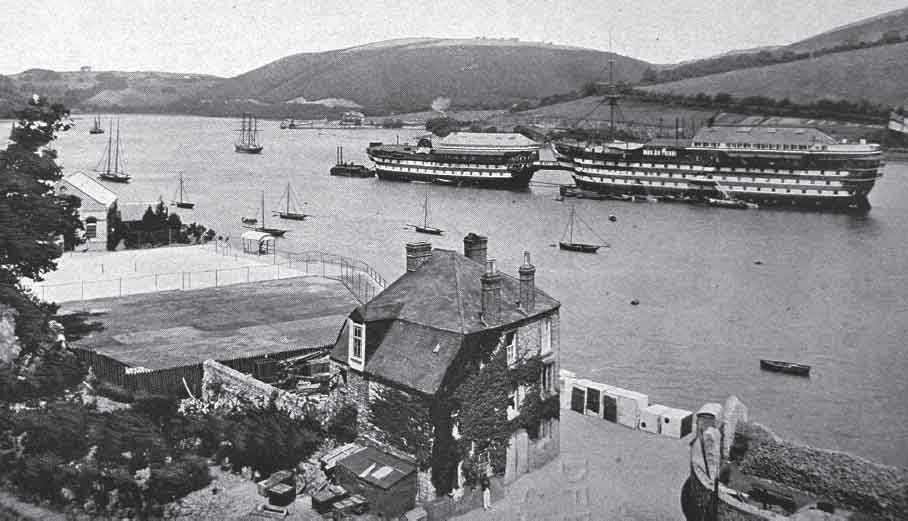

Usborne entered the training ship HMS Britannia in May 1897. This was just a few years before it was replaced by the Britannia Royal Naval College, the foundation stone of which was laid in 1902. An old three-deck, ship-of-the-line, had been moored in the Dart estuary since 1863, being joined (by means of a bridge between them) by the two-decker, Hindustan, in 1864, though the first Britannia was replaced by a larger and more modern vessel in 1869.

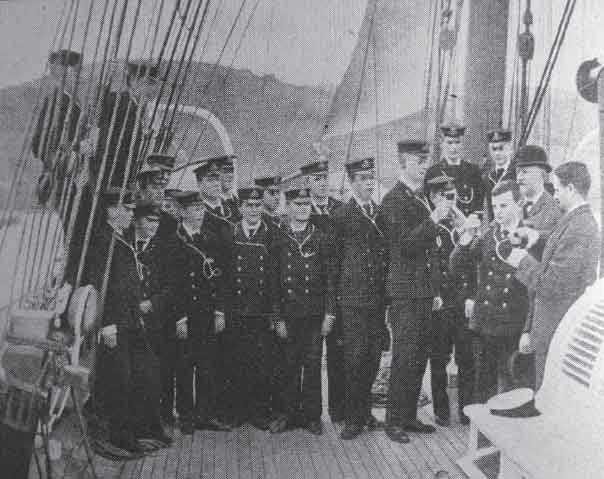

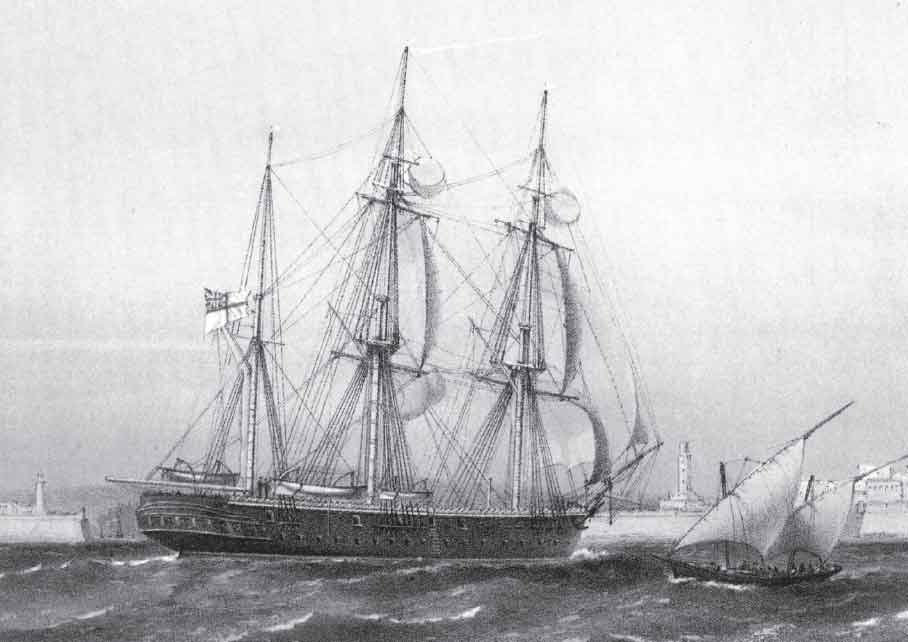

Britannia & Hindustan on the River Dart in the 1890s.

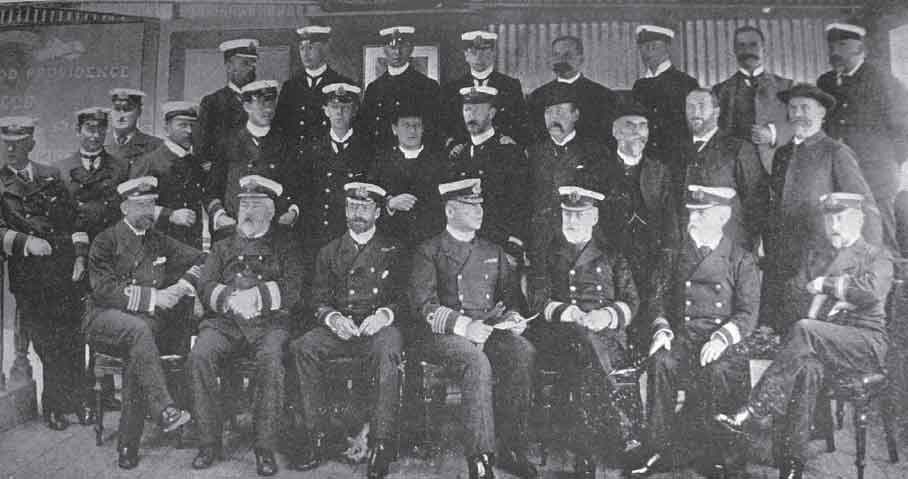

In 1897 the ship was under the command of Captain the Hon A.G. Curzon-Howe, ‘a dignified aristocrat of the old school’1 who had the reputation of being one of the politest and most gentlemanly officers in the navy. Mrs Curzon-Howe also lived on board with their small son and was loved by the boys for the kindness she showed to them.2 The second in command was Commander Christopher Cradock, who was always immaculately dressed, with a pointed, neatly-trimmed dark beard, which reminded the boys of Sir Francis Drake.3 He was also a popular Master of Beagles and would die a gallant death against hopeless odds at the battle of Coronel in 1914. Both were fine role models for a cadet to follow.4 The Naval Instructor, the Reverend N.B. Lodge, was remembered as the best teacher one cadet, who would have an illustrious career, ever had.5

Few records remain from Neville’s time there, with results for only two of his four terms having been retained in the college archive:

The staff of HMS Britannia in 1898.

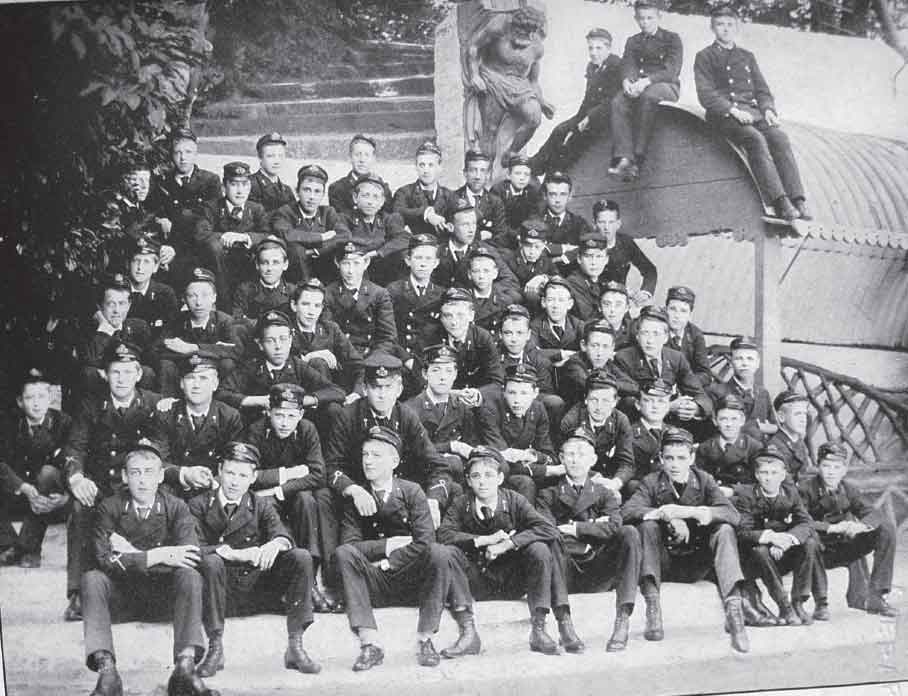

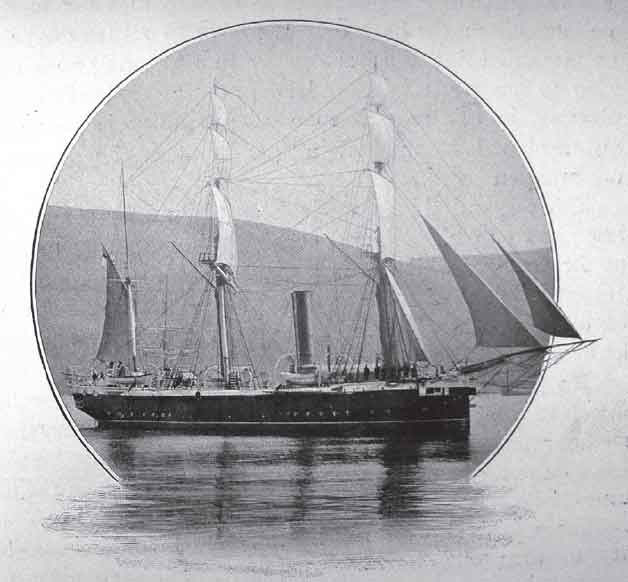

Classes would have included navigation, astronomy, topographical and mechanical drawing, the understanding of steam and steam machinery (described by one cadet as, ‘the steam picket boat and other such oily delights’),6 and a considerable amount of mathematics; in what would have been a spartan existence, ‘in which boys learnt to sail, navigate, command and, above all, be commanded.’7 The cadets slept in hammocks slung below deck in the fashion of Nelson’s seamen. A cold saltwater wash on deck marked the beginning of a long working day, which began with a bugle call at 0630 and ended with lights out at 2130, devoted to inspection, meals, classes and exercise – including gymnastics, boating, games and swimming. The cadets were referred to by their progression through the four terms as ‘New’, ‘Three’, ‘Sixer’ and ‘Niner’. Usborne was fortunate to experience sea time on Britannia’s tender, HMS Racer, a handsome barque-rigged sloop of 970 tons, which had arrived in 1896, and took the third and fourth terms’ cadets on cruises in the English Channel to improve their seamanship, engineering and navigation skills. He would also have been present during Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in June 1897. The procession in London allowed for the participation of 100 cadets and those who were not chosen for this were taken to the Review of the Fleet at Spithead. In the term ahead of Usborne was Cadet A.B. Cunningham (later Admiral of the Fleet Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope, KT, GCB, OM, DSO), who later recalled that the review took place on a brilliantly fine morning, followed by an afternoon of lightning, thunder and torrents of rain. The Royal Yacht, Victoria and Albert, passed through the fleet, arrayed in line after line, with ships’ companies cheering and bands playing:

‘What a brilliantly fine day, all the ships dressed overall with flags and painted in the old-time colouring of yellow masts and funnels, white upper-works, black hulls and salmon-coloured waterline, divided from the black by narrow white ribands. The senior cadets, in the Racer, manned yards as the Queen went past.’8

Cadets at Britannia in the 1890s.

As a cadet Neville would have had sea time on board HMS Racer.

That evening the cadets, who were accommodated on board the old stores ship, Wye, changed out of their best uniforms and white gloves, and, refreshed by a saltwater bath on deck, spliced the main brace and drank the Queen’s health with a glass of 1848 port.9

Discipline was strict, but there were instances of bullying of younger cadets by their seniors, though in the years following the Jubilee these were much less than in the decade before.

Splice the Main Brace – cadets celebrating the Diamond Jubilee in 1897.

Bullying had not been stamped out in 1897–98, but it was not severe; an expression of the element of sadism with which many boys seem to be endowed in their youth.10

Indeed, Captain Curzon-Howe showed his attitude to bullying right away when he ordered three bullies to be flogged before all the assembled ship’s company and cadets. It is reported, however, that he also had to deal with over-protective mothers, as in the case of one who wrote to him asking that he make sure that her son wore his drawers in cold weather, a wise precaution perhaps, but not, it may be thought, a normal part of a captain’s duties.11

Be that as it may, a future admiral noted that this regime was likely to suppress independence and initiative in, ‘our future naval officers’. The most notorious example of this had been on 22 June 1893, off Tripoli, when HMS Victoria was rammed and sunk by HMS Camperdown, resulting in the deaths of the C-in-C Mediterranean Fleet, Vice Admiral Sir George Tryon, twenty-two officers and 336 ratings. The admiral had given an order for two columns of ships to turn towards each other, which was a tricky and hazardous manoeuvre; the captains of the two leading battleships carried out the order without questioning its desirability and, when the collision seemed inevitable, did not react swiftly enough without a direct countermanding order from the admiral, by which time it was too late. Tryon remained on the bridge as his flagship sank, and was heard to murmur, ‘It’s all my fault.’ The executive officer of HMS Victoria was fortunate to escape unscathed, as indeed was the Royal Navy, as the officer concerned was Commander John Jellicoe (1859–1935). (Jellicoe subsequently became Admiral of the Fleet and an Earl, holding many major naval appointments between 1905 and 1917, and will feature more than once in this story.) At the subsequent court martial of Rear Admiral Markham, who was aboard HMS Camperdown, he was asked, ‘if he knew it was wrong, why then did he comply with the fatal order?’ He replied that he thought, ‘Tryon must have something up his sleeve – a triumph of hope and obedience as compared to logic, experience and initiative.’ The court found Tryon to blame, but accepted that it would be fatal for the navy to encourage subordinates to question those set in authority over them.12

It should be noted, however, that in the 1890s, efforts were being made to modernise the tuition given in Britannia; for example, reforms were instituted by Captain A.W. Moore in 1895, giving his lieutenants much greater direct responsibility for the cadets’ welfare and progress. A near contemporary of Usborne was the distinguished naval airman, Vice Admiral Richard Bell Davies, VC. He recalled the curriculum at Dartmouth as having:

‘Remained unchanged for very many years, and consisted almost entirely of mathematics and seamanship; we had our full measure of the myriad names of the standing rigging, little of which specialised knowledge was to be of any use to my later career.’13

A few years earlier, at the start of the 1890s, a cadet writing as ‘Navilus’ was of the opinion:

‘On board HMS Britannia, one day is very much like another, which, though somewhat monotonous, has the advantage (if it be one) of making the time fly fast.’14

Another cadet, William Henry Dudley Boyle, who would become Admiral of the Fleet, and also the 12th Earl of Cork & Orrery, later wrote:

‘The education given to us was almost entirely technical, or directed to that end; and, though it is true that English literature figured in the curriculum, as during our four terms there we never got beyond Southey’s, Life of Nelson, in this it hardly extended our horizon.’15

Yet another gives a much more favourable and positive view:

‘The elite of the Navy, in its various ranks and ratings, was on hand to guide us, with a lieutenant in general charge of each term and a naval instructor taking his class in trigonometry and navigation throughout. These instructors kept control and imparted knowledge in a manner I have never known excelled. From a varying acquaintance with arithmetic, algebra and Euclid, we were introduced to plane, and later to spherical trigonometry, advancing to celestial navigation. After four terms of three months, they sent forth boys who could not only solve spherical triangles and prove the formulae they employed, but who could also work a ship’s reckoning by the sun. We learned French and drawing from civilian teachers, steam from an engineering officer and we looked to the chaplain for the weekly lesson in scripture. But we had already been well grounded in that subject, a high standard being demanded in the entrance examination. Brisk petty officers attached to each term, the very salt of the earth and sea, were perhaps our widest and most shrewd counsellors on board. Others of the same rating taught us seamanship in a delightful model room and showed us how to row or sail.’16

Neville would have been present at an end of term ceremony in 1897 or 1898 when the famous admiral, who was giving away the prizes, made the usual stirring speech about the glorious history of the Royal Navy and the many victories won against the old enemy. As he came to a climax he beseeched the cadets never to forget St Vincent and Trafalgar in particular, thumping his fist into his other palm for emphasis, at which the French were firmly put in their place. The rousing speech did not go down too well with the four French officers, attending as guests of the captain, nor with the cadets who sat in embarrassed silence; it was, ‘a melancholy frost.’17 He may also have received some most irregular, but doubtless very enlightening, extra-curricular education, as more than one cadet noted that the daughter of the canteen manager was prepared to raise her skirts for interested onlookers for the sum of one penny.18 Perhaps Britannia did not provide a fully-rounded education, but she certainly had her unique selling points.

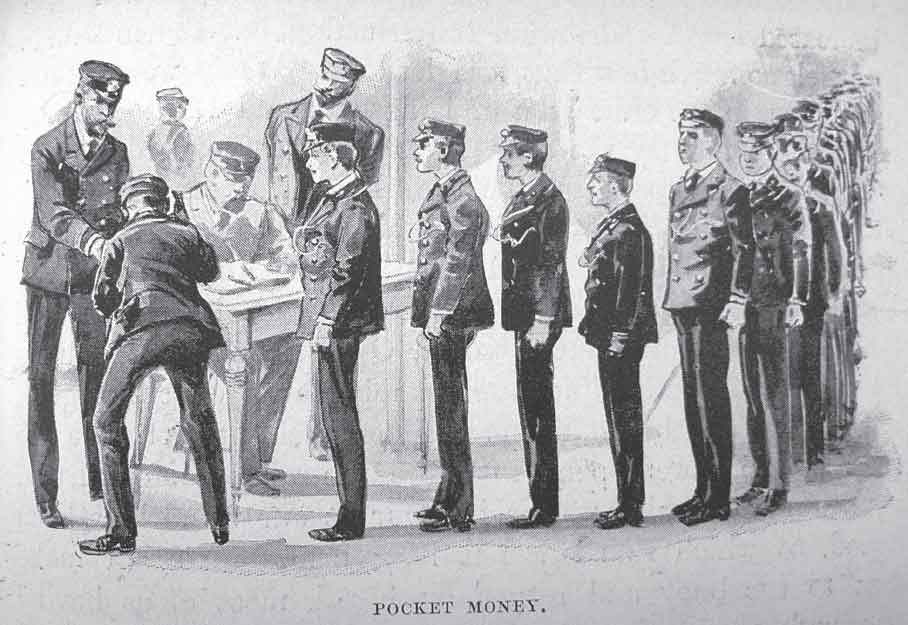

Cadets receiving their pocket money.

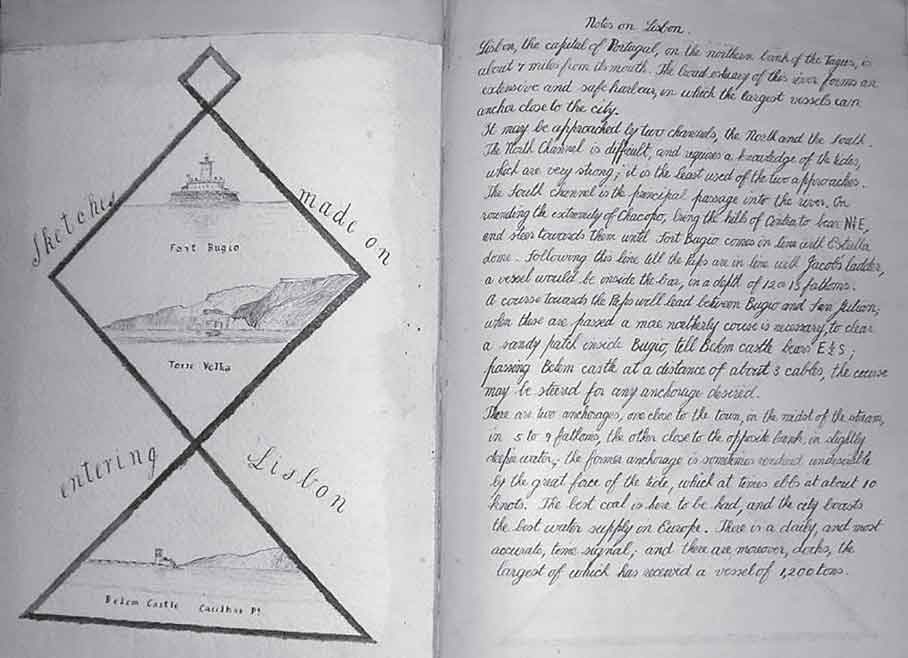

Sea Training

From September 1898 to March 1902, Neville Usborne served as cadet midshipman (from 15 August 1898), progressing from ‘wart’ to ‘snottie’ and sub-lieutenant (promoted 15 March 1902). His first ship was the Majestic Class battleship of 14,900 tons, launched in 1895, HMS Prince George. (This was the last RN battleship class to have twin side-by-side funnels, the first to have design uniformity, and the first with fully enclosed 12-inch gun turrets protecting the gun breeches and shell handling machinery.) Then came the Canopus Class battleship, HMS Canopus, of 12,950 tons, launched in 1897 (which set the pattern for pre-Dreadnought battleships), with detached duties in Torpedo Boat No 96, of 130 tons, launched in 1893; the sail training ship HMS Cruiser of 1130 tons (built as a wooden screw sloop in 1852 and converted to sail in 1872 to give young officers and seamen experience handling a square rigged ship – the last squadron of naval ships to put to sea under canvas was in 1899) and the store ship HMS Tyne of 3650 tons, launched in 1878. Most of his service during these years was in the Mediterranean and around the British Isles. He kept two meticulously written and beautifully illustrated logbooks – so his handwriting must have improved under naval tutelage. Technical drawing was not neglected; the pen, ink and watercolour illustrations were both decorative and analytical in nature. Completing the log was a compulsory part of a midshipman’s training; it was inspected regularly by a supervising officer and by the captain.

The late Victorian Royal Navy; a Lieutenant with Midshipmen and a Cadet.

HMS Prince George.

HMS Cruiser.

Top and above: Three pages from Midshipman Neville Usborne’s Logbook, showing the great care he took with his handwriting and sketching. (via Sue Kilbracken)

The log records a visit to Lough Swilly and then to Belfast Lough in July 1899, as part of the Channel Squadron under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Harry Rawson. HMS Prince George was one of twenty-seven warships taking part in naval manoeuvres. There was considerable interest in the local newspapers, The Northern Whig and the Belfast Evening Telegraph:

‘Never before was there such a formidable fleet of war vessels in Belfast Lough as that which now lies off Bangor.’19

Vice Admiral Sir H.H. Rawson.

The object of the manoeuvres, according to the Admiralty, was:

‘To obtain information as to the most advantageous method of employing a considerable body of cruisers in conjunction with a fleet.’20

A secondary objective was:

‘To throw some light on the relative advantages and disadvantages of speed and fighting strength, and the working of destroyers and torpedo boats.’21

Thousands of spectators descended on the seaside resort of Bangor to view the warships from the shore and also to take passage on pleasure boats offering trips around the fleet. A two-hour cruise from Donegall Quay, Belfast, on the Barrow Steam Navigation Company’s ‘Fine Paddle Steamer’, Manx Queen, was advertised at 1/6 (seven and a half pence). The warships were described in detail in the newspapers, it was revealed that HMS Prince George, completed in 1896 at a cost of £885,037, displaced 14,900 tons, carried four twelve-inch and twelve six-inch guns, engines which could develop 12,000 horse power, had a complement of 757 and was commanded by Captain Sir Baldwin Wake Walker, RN, Bart. Young Neville Usborne noted in his log that visitors came aboard after Divine Service on Sunday, 23 July. The following day was much less enjoyable no doubt, as it was spent in coaling ship, a backbreaking and messy business shifting an average of seventy-three tons per hour, three of which Neville spent in the hold at the sharp end of the toil. After several days of further drills and evolutions, the fleet weighed anchor on 29 July and proceeded to sea to, ‘clear for action and commence hostilities against B Fleet.’22 The fleet must have made a magnificent spectacle painted in the old colours: red boot-topping, black sides, white upper works, and yellow masts and funnels. It would be another four years before the general order was given to paint all ships grey to reduce their visibility (apart from destroyers, which were to be black in home waters and white in the Mediterranean).

HMS Canopus.

In late 1899 he was posted from the Prince George to join Canopus, which was commissioning for the first time, and was allowed to proceed by packet ship in order to have time for home leave. In Usborne’s case the packet ship was the Orient Line’s SS Oroya of 6057 tons, on its regular passage from Australia to England, in which he embarked at Gibraltar on 20 November. During his time serving on Canopus he received two cash prizes of £10 and £3, awarded to junior officers afloat for proficiency in French and German.

Greenwich and Excellent

He left the ship for the RN College, Greenwich, in March 1902, with a highly satisfactory report from Captain H.S.F. Niblett, being graded very good in respect of General Conduct, Ability and Professional Knowledge, noted as having temperate habits, winning praise for a good colloquial knowledge of French, German and Italian, and being described as physically strong, zealous, very able and promising. At Greenwich, he took his oral seamanship examination. This took the form of a gruelling grilling, which could last for several hours, from a board composed of two captains and a commander. He passed with 912 marks out of a possible 1000 and was awarded a first-class certificate, which meant promotion to acting sub-lieutenant. Life at Greenwich in those days was described as follows:

‘The sudden transition to the college at Greenwich (from service at sea), in close proximity to London, with considerable freedom and increased pay, proved too much for the majority, who laid themselves out to have a good time. Of course there were some level-headed ones who worked hard, and others, more gifted than their companions, who absorbed the necessary knowledge and yet managed to find time to enjoy themselves, but these were a minority. The college never got the return it should have had for all the trouble taken over sub-lieutenants’ education.’23

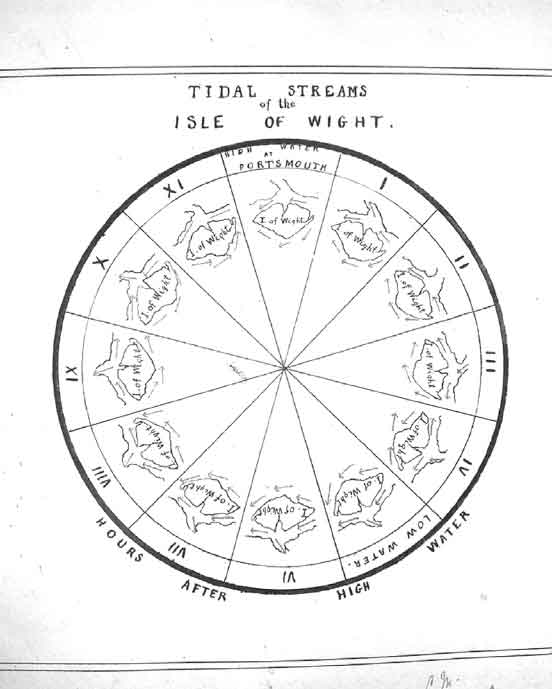

It would appear that Usborne was either clever or studious (or both), as, over the next fifteen months, there was further study and examination in navigation (parts I and II)24 and pilotage, proficiency in which was examined at the Hydrographic Department in the Admiralty building in Whitehall. The course then migrated to the Royal Naval College, just inside the dockyard gates at Portsmouth, for the gunnery course at Whale Island and the torpedo course at Devonport. The experience was described by one of Usborne’s contemporaries, who had entered Dartmouth in 1897, just a term before him, but who was a member of the same course, as follows:

‘We lived here, went down each morning to the Excellent steps, and were ferried across the harbour to Whale Island – otherwise HMS Excellent, the Alma Mater of naval gunnery – for the day’s work. Here everything possible was done to make miserable the lives of the sub-lieutenants. We were chivvied and bullied. Maybe we deserved it; but I cannot believe it was necessary, or that it did us any good. Being shouted at on parade, or for some minor fault, merely made me feel mutinous. I was glad to get away from the detestable place on 13 March 1903, with a second-class in gunnery, and a certificate awarded at the end of our courses stating that I had conducted myself with sobriety, but that my general conduct was not satisfactory. This smudge on my character was quite unjustly bestowed, but fully in keeping with the general atmosphere that then prevailed at Whale Island, which was harsh and inhuman. I believe my bad certificate was due to the following incident. At the end of the examination we had to return all the leather equipment and gaiters with which we had been issued to a hut on the parade ground. After a good lunch about six of us set out to do this. We found the hut locked and nobody inside, as there should have been. Not wishing to be delayed and to miss the boat to the mainland, we threw the gear in through the open window. One of the party, making insufficient allowance for a good lunch, broke a window, while an inkpot was upset and the hut generally in a mess when the storekeeper returned. So all of us were served out with these unfavourable certificates. I afterwards heard that, with the exception of myself, they all complained and managed to get them altered. I never heard of this, so my certificate as originally written is one of my proudest possessions. We next went to the Vernon for a six weeks’ course in torpedo. Here conditions were far more human. The instruction was good; we learnt a lot.’25

Usborne gained first-class passes apart from Part I navigation, in which he scored a second-class pass. He was awarded the Ryder Prize of £10 for this achievement.26

Developments in Military Ballooning in the 1890s and early 1900s

While Neville was learning his trade, a permanent Balloon Section and Depot RE had been formed in May 1890, with appropriate provision being made in the Army Estimates, moving from St Mary’s Barracks, Chatham, to the south camp in the Royal Engineer Lines at Aldershot in 1891. It now numbered three officers, three sergeants, and twenty-eight rank and file, with Templer having been promoted to lieutenant colonel and appointed Officer-in-Charge of Ballooning. It was about this time that an early army aeronaut was reproved for being without helmet, sword, sabretache or spurs whilst on duty, none of which would have been either necessary or sensible by way of flying kit.27 In the words of a former officer-in-charge of the Balloon Establishment:

‘This may be regarded as the termination of the experimental stage and the recognition of balloons as a necessary adjunct of the army.’28

Military balloons were now classified into five types according to their capacity: A class: 13,000 cubic feet (368 cubic metres), V class: 11,500 cubic feet (325 cubic metres), T class: 10,000 cubic feet (283 cubic metres), S class: 7000 cubic feet (198 cubic metres) and F class: 4500–5000 cubic feet (127–142 cubic metres). Steady improvements had also been made to the rigging, nets, valves and other accessories. A new pattern of gas cylinder had been introduced, of greater capacity and efficiency.29

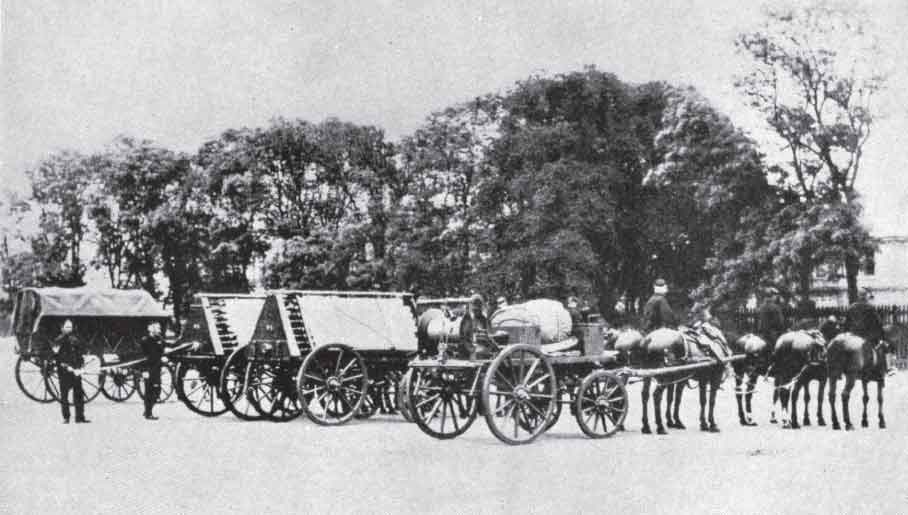

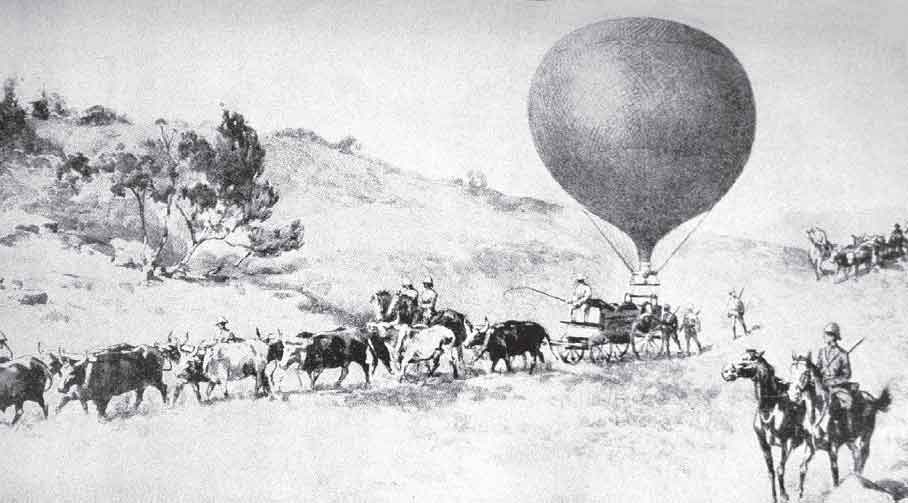

Balloon transport in 1890, showing a balloon wagon, two of the three tube wagons and an equipment wagon. Major C.M. Watson, RE, is in command.

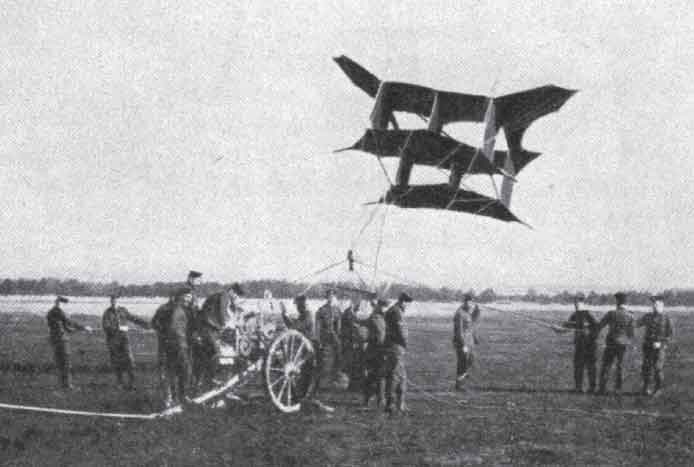

Another aspect of early army aviation was the man-lifting kite. Major B.F.S. Baden-Powell, Scots Guards, the brother of the founder of the Boy Scouts, developed a kite for reconnaissance and persuaded a sapper to be taken aloft by this means on 27 June 1894. His kites were used during the Boer War for observation and photography. Later, the Texan, Samuel Franklin Cody, was employed by the War Office to experiment with observation kites on Woolwich Common and as a kite instructor in the Balloon Section of the Royal Engineers at Farnborough. If being in the wicker basket of a balloon felt vulnerable, then the prospect of dangling from a kite a few hundred feet in the air above a battlefield must have been a proposition for only the very brave or the most foolhardy.

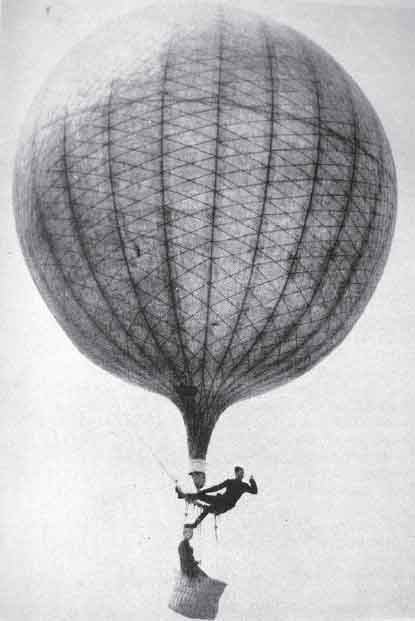

The Royal Engineers in 1893. Lieutenant H.B. Jones is in the basket. (Museum of Army Flying)

A balloon and kite winch with a kite.

[Author’s note: Major B.F.S. Baden-Powell (1860–1937) made his first balloon ascent in 1881. In 1894 he was attached to the Balloon Section at Aldershot, and made numerous ascents over the next decade and more. He joined the Aeronautical Society in 1880, becoming Honorary Secretary in 1896, founding the Aeronautical Journal in 1897 and being appointed President in 1902. On 27 June 1894, he was the first to be taken aloft by a man-lifting kite. These were later used during the Boer War for reconnaissance and photography. In 1908 he was the second Englishman to fly with Wilbur Wright.]

An article appeared in the Strand Magazine in 1895, which gave a very detailed and interesting description of the work of the Balloon Section:

‘The next European war will be a strange and fearful thing; everyone seems pretty sure about that. Writers of fiction with strong imaginations and a smattering of military science are constantly producing forecasts of this fascinating subject. We learn that Mr Maxim’s guns will be very much to the fore; probably also, Mr Maxim’s embryonic flying machines. Then we hear of messenger dogs, swarms of poisonous flies, and, above all, – in a dual sense – war balloons, whose mission will be to drop charges of dynamite and things of that kind upon all and sundry whom it is advisable to destroy.

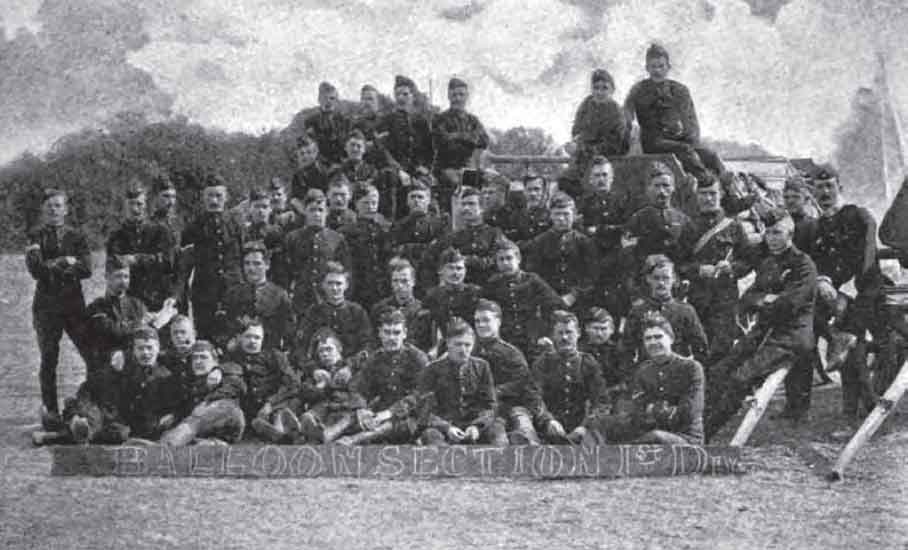

‘All this leads up to the fact that we have a full-blown School of Ballooning at Aldershot, under the direction of Colonel Templer, whose name for many years has been associated with advanced military science, especially as regards the war balloon. The school at Aldershot is at present established in the Stanhope Lines, where large buildings have been erected on what was, a few years ago, nothing but a dangerous swamp. Colonel Templer is assisted in his very interesting work by Sergeant-Major Greener; and the accompanying group shows the entire staff of the first division of the Balloon Section when in the field, i.e. these men work the balloon.

‘Without exception, these men are enthusiasts in their work, and, although they are associated with what may be described as the most interesting and novel branch of the service, they themselves are by no means inflated. At any rate, there is very little doubt that the British taxpayer got his quid pro quo – and perhaps a little more – in return for last year’s ballooning grant, which was rather less than £3,000.

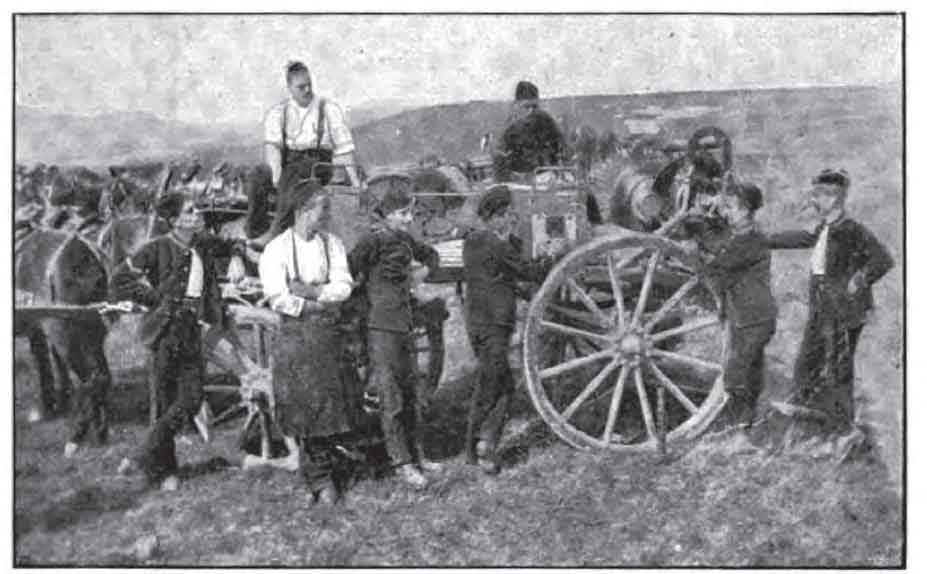

‘Colonel Templer generates his own gas from diluted sulphuric acid and granulated zinc. The lifting power of the hydrogen generated this way is much greater than that of ordinary coal-gas, but then its cost is much more. When manufactured, the hydrogen is compressed at ‘100 atmospheres’ pressure and stowed away, so to speak, into huge Siemens steel cylinders, each averaging about 90lbs in weight. Ten of these elongated tubes are placed, for conveyance to the field of battle, upon admirably contrived wagons, usually drawn by horses; of course, under certain conditions, the gallant Colonel could utilize the baggage train, of which he is so great an advocate.

A group photo proudly displaying a sign reading Balloon Section. (The Strand Magazine – Charles Knight)

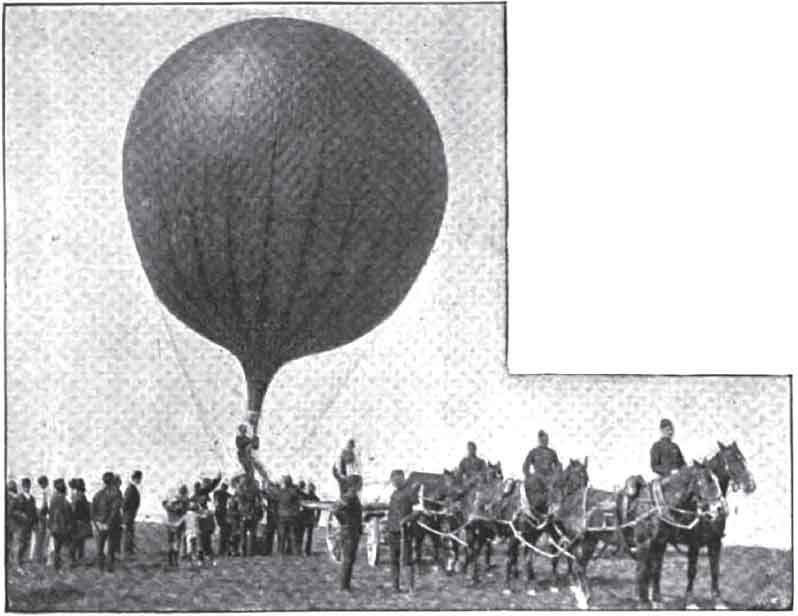

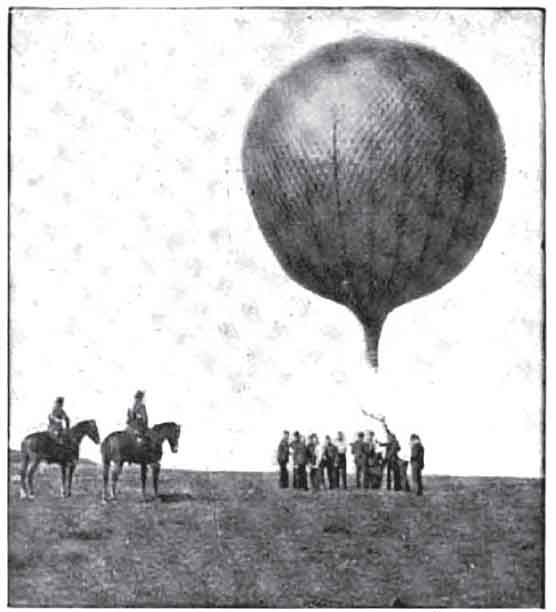

Inflating a war balloon. (The Strand Magazine – Charles Knight)

‘It takes, as a very simple calculation will immediately show, two wagon loads of gas to inflate a balloon of 10,000 cubic feet capacity, such as shown in the accompanying illustration.

‘Here we have the working staff, with two lieutenants in command of the section, the wagon and its team, and lastly, the inevitable crowd of curious onlookers, with the still more inevitable sprinkling of the small boy genus, without which no operation of the kind would be complete.

‘The man standing upon the car affixes one end of a screw nozzle to the mouth of a gas cylinder, while another of the engineers places the connecting tube to the nozzle of the balloon. The man on the car then gently turns on a very nicely constructed valve, which permits the compressed gas to leave the cylinder only at a very moderate rate. The balloon inflated, we will suppose that Lieutenant Hume and a brother officer are told of the duty of reconnoitring the enemy’s position. The two officers take with them a map of the surrounding country, on the scale of two inches to the square mile. Of course, they are provided with field glasses, and the moment they discern the enemy and are able to gauge his strength, they make certain notes upon the map, using for this purpose pencils of various colours; one colour denotes cavalry, another infantry, and so on.

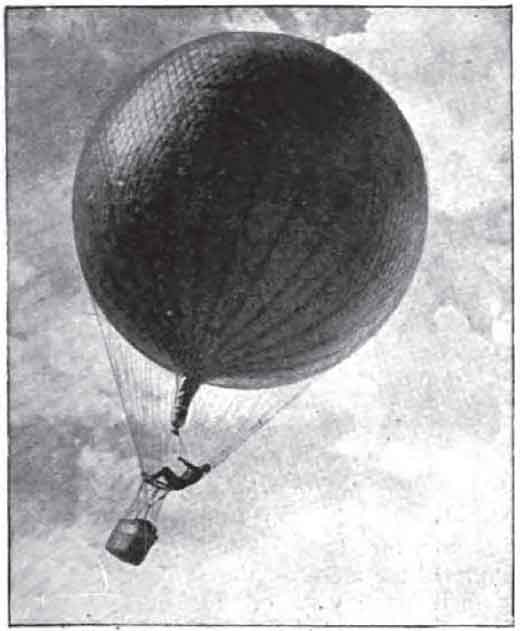

‘In the next picture we see that everything is ready; the crew are on board, and the men who are holding the giant captive are awaiting the order to “Let go”. The moment this order is given the immense aerostat shoots straight up like a rocket, but pressure is gradually brought to bear on the connecting rope, and, when at an altitude of several hundred feet, the upward course of the huge machine is checked, and it sways gently to and fro, while the skilful officers in the car anxiously scan the magnificent prospect of country far below them. The moment any definite information is obtained as to the enemy’s movements, the map spoken of above is marked according to such information and then placed in a canvas bag to which a ring is attached in such a way that it glides swiftly down the rope to the ground, where a mounted orderly is in waiting. The orderly immediately gallops off with the very latest intelligence to the general in command.

‘The British war balloon has long since ceased to be manufactured from silk – though this material is even now generally used by professional parachutists and aeronauts for their “envelopes”. After many experiments, however, a perfectly impermeable material has been manufactured from ox-gut by a series of secret processes.

Awaiting the order to ‘Let Go’. (The Strand Magazine – Charles Knight)

‘It is an interesting fact that in the manufacturing shed at Aldershot, women are employed in the making of the balloons, which are for the most part of a capacity equal to 10,000 cubic feet, and have, when fully inflated, a lifting power of something like 700lb.

‘There are at present in the storeroom at Aldershot, thirty-two fully equipped balloons, ready at an hour’s notice to go on active service; and what is more, if, in actual warfare, they are found as useful as they have been in manoeuvres, their actual value will not have been at all overestimated.

‘The envelope of the balloon is enclosed in a network of very strong cord, which is fastened below the nozzle of the balloon to a stout hoop that supports the car. The cord is manufactured by a justly-celebrated firm of rope makers in the North of England, from hemp specially grown in sunny Italy; and although it is so light that a section 100ft long does not weigh a pound, and it is only about ¼in. in diameter, it will stand a strain of 500lb. without breaking. I have myself seen this cord practically tested by Sergeant-Major Greener on a dynamometer. The car of the war balloon accommodates a couple of men, and it is made of very strong wicker work. It is 2ft 3in. deep, the same in width, and 3ft 6in long. This car is fastened to the hoop above by very strong ropes; and of course for reconnoitring purposes, it is supplied with a grapnel, a captive rope, a photographic outfit, and many other articles that are carried in the common or Crystal Palace variety of balloon.

‘In the next illustration is seen the most direct and valuable mode of communication between the officers in the car of the war balloon and the forces below. I refer to telephonic communication. In the picture it will be seen that a light wagon carries the necessary electrical plant. On the occasion of my own visit to the scene of operations, I watched an orderly gallop up to this wonderful piece of portable mechanism, and he roared into the cart as it were, “Any fresh information?”

‘The officer, with a truly astonishing quickness, gained most important news, receiving a reply which ran as follows: “There is a large body of cavalry on your right flank, behind the hill, deployed ready to charge the supports.” This message came in an amazingly sharp and articulate voice – a veritable viva-voce message from the clouds.

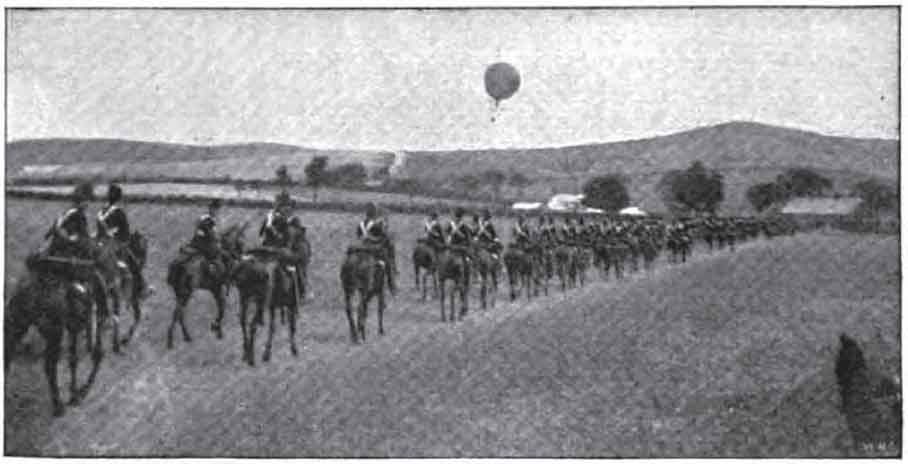

‘The accompanying reproduction shows the Aldershot war balloon “Talisman” reconnoitring at such an altitude as to command the entire radius of country over which the manoeuvres are being conducted. It will be noticed that on the windward side the balloon is rather flat, instead of convex; this indicates that there is a vacuum, so it is coming down to be refilled. The body of cavalry seen is being wholly guided by instructions received from the “Talisman”.

A portable receiving station of the aerial telephone. (The Strand Magazine – Charles Knight)

War balloon directing cavalry. (The Strand Magazine – Charles Knight)

‘The system of reconnaissance by pencil-coloured maps dropped from the balloon at present holds the field against photography; but it must not be assumed that the camera is a wholly futile ally on the battlefield. As a matter of fact, most successful and valuable pictures are constantly obtained, showing in most beautiful detail the nature of the surrounding country and the obstacles to be encountered. You must remember, though, it takes at least half an hour to photograph, develop and dry the negative, and print a proof; from which it is obvious that information given to the commanding officer by this means is a little stale, as it conveys to him rather where his opponent was, than where he is at the moment.

‘When the officers in the balloon have procured all the information possible regarding the movements of the enemy, the war balloon is brought down, and is towed into some sheltered valley by the men of the balloon section, as is seen in the last photograph reproduced here; then, of course, the balloon is placed under sentry protection. Not that much protection is needed, save, perhaps, from the derision of the small boy genus before referred to. I distinctly remember seeing a balloon towing party followed by a troop of gamins, who, far from being impressed by the huge machine, gave tongue from time to time and implored the men to, “tike it ‘ome”.

The towing party at work. (The Strand Magazine – Charles Knight)

‘Such is the work of the captive balloon. There are times, however, when Sergeant-Major Greener and other officers release the captive and travel to different parts of the surrounding country at a speed of perhaps forty miles an hour. As one might imagine, however, this speed is hardly noticed by the occupants of the balloon.

‘At the Aldershot School of Ballooning, selected officers go through a course of instruction at appointed seasons; and altogether, we may feel assured that we are well to the fore, as a nation, in the science of belligerent aeronautics.’30

On 1 April 1897, Lieutenant Colonel Templer became the first superintendent of the Balloon Factory, directly responsible to the War Office, at a salary of £700 per annum, as it was now recognised officially for the first time. His own title had, until then, been Instructor in Ballooning, which failed to do full justice to his position and duties. This period also brought about the publication of the first comprehensive service guide, the Manual of Military Ballooning, which was compiled by Captain B.R. Ward, RE. Free run ballooning became a popular part of the courses which were held for officers, not only in the Royal Engineers, but also from other arms and a selected few from Staff College. By this means aeronauts could learn to control and land a captive observation balloon in the event of it breaking away from its cable. It was also looked on as a skill which might come in useful in providing transport out of a besieged location. The normal drill on a free run was to plot the course taken by means of Ordnance Survey or Bradshaw railway maps. On landing, the balloon would be deflated and packed into its basket, a telegram would be sent to Aldershot and the aeronauts would return by train with the basket travelling in the guard’s van.

In October 1897, The Times featured a column titled Military Ballooning, which described at some length the recent activities of Captain G.M. Heath, RE, and his balloon section supporting the Horse and Field artillery as they exercised on the gunnery ranges at Oakhampton and Lydd. The writer commented that the large size of contemporary armies and the extensive areas of country which they occupied rendered reconnaissance from the air ever more useful. He added that most observational flights were crewed by two aeronauts, one mounted in the netting to manage the equipment and the other in the wicker car, therefore able to devote his entire attention to observing, recording and sketching. The potential vulnerability of balloons to enemy fire was discussed and dismissed as being not as great a problem as might be supposed. The question of the dirigible balloon was also raised, but the problem of a suitable means of steering in all but the lightest of winds was regarded as admitting that there was no easy solution.31

Surveying the enemy’s country. (The Strand Magazine – Charles Knight)

In 1899 an international declaration was made, operative for a period of five years, following the First Hague Peace Conference, the Hague Convention. One of its provisions was to prohibit the launching of projectiles or explosives from balloons or any other kind of aerial vessel.

The Army used balloons for observation, field sketching of enemy positions, artillery spotting purposes and also as communications relay stations by heliograph in the Boer War between 1899 and 1900, with 1st Balloon Section, Major H.B. Jones, RE, providing notable service at Magersfontein, Kimberley, Paardeberg and Pretoria; 2nd Balloon Section, Major G.M. Heath, RE (later Major General Sir Gerard), at the siege and relief of Ladysmith and 3rd Balloon Section, Brevet Major R.D.B. Blakeney, RE, (later Brigadier General) at the relief of Mafeking. Some thirty balloons were sent to South Africa, including the Duchess of Connaught and the Bristol. Such was the requirement that the existing balloon establishment had to be reinforced at short notice by the recall of personnel with previous experience.32 The Commander of the British Forces, Field Marshal Lord Roberts, VC, appreciated the efforts of the Balloon Sections, ‘the captive balloon gave great assistance by keeping us informed of the disposition and movements of the enemy.’33 The Boers were rather less impressed, though it could have been worse. They feared that balloons would be used for the aerial bombardment of the Boer capital, Pretoria. The Balloon Factory had indeed worked out a general scheme for bombing from the air, but this was not taken any further. The Boer leader, General Cronje, commented tersely; ‘The British were greatly assisted by balloons.’ A more detailed survey was made by Colonel Arthur Lynch, who was Australian-born of an Irish father and a Scottish mother, and who was serving with the Boer army. On 27 March 1902, he gave a lecture in Paris entitled, Du rôle des ballons militaires anglais dans la guerre de l’Afrique du Sud. He paid tribute to the expertise of the Balloon Sections; ‘I take this occasion to say that the English take pride in themselves, and perhaps not without reason, that they possess the best balloon service of all the armies of the world.’ Then he added, ‘the balloons have been of great value to the English on several occasions. Observations made by balloon often enabled the English to note exactly the position of a battery, a laager, an encampment, or some fortifications; or even troop movements made in preparing for a major attack.’ He noted that aerial observation greatly increased the accuracy and effectiveness of artillery fire, much to the annoyance of the enemy, who saw the balloons as, ‘a symbol of the scientific superiority of the English’.34

A contemporary artist’s impression of the 1st Balloon Section being deployed in the Boer War in 1900.

[Author’s note: Lynch (1861–1934) had a remarkable career, gaining engineering, philosophy, science and medical degrees during his education in Melbourne, Berlin, Paris and London. He first went to South Africa as a war correspondent and then persuaded President Kruger to appoint him to the rank of colonel in the Boer Army. He served with distinction with the 2nd Irish Brigade, which, if truth be told, was rather a motley band of diverse nationalities. In late 1900, he visited the USA to plead the Boer cause and befriended the future president, Theodore Roosevelt. On his return to the United Kingdom he was elected as the MP for Galway (from where his family had originated). On presenting himself at the Houses of Parliament he was arrested, tried for high treason, and condemned to death on 23 January 1903. After the intercession of President Roosevelt, the King granted him a free pardon. He continued with his eclectic range of studies and also became the MP for West Clare in 1909. In 1918, following useful war work, he was appointed to the rank of colonel in the British Army. After the war he returned to medicine and authorship.]

The Boers did make attempts to shoot down the balloons, but they did not succeed, despite perforating envelopes on occasion and wounding an aeronaut once. A balloon could sustain a number of bullet holes while retaining much of its effectiveness and was easy to repair. This experience no doubt contributed to the later debate as to whether or not airships could survive on the battlefield. The goldbeater’s skin envelopes also stood up well to hard use and retained their gas well. Teams of oxen or mules towed the balloon wagons in this campaign, which was often a slow and frustrating process, even though Templer was in South Africa as the Director of Steam Road Transport in 1900, where his traction engines did much other useful work.

While Colonel Templer was engaged in South Africa, his duties at the Balloon Factory were carried out by Acting-Superintendent Brevet Lieutenant Colonel J.P.L. Macdonald, RE (later Major General Sir James), who had prior experience of the role when he was left in charge at Chatham in 1884–5, when Templer and Elsdale were serving in the Sudan and Bechuanaland respectively. When Macdonald was selected to lead the expedition to China in 1900, his successor as Acting-Superintendent was Major F.C. Trollope, RE, who had been second-in-command in Bechuanaland.

Another section was sent to China, with the balloons Tugela and Teviot, commanded by Captain A.H.B. Hume, RE, to support the International Relief Force for the siege of the Legations in Peking (On the conclusion of activities in China it became the Experimental Balloon section at Rawalpindi in India.)35 and yet another to Australia under 2nd Lieutenant T.H.L. Spaight, RE, for the Commonwealth inauguration in January 1901. Two balloons were supplied to Captain Scott for his Antarctic expedition in the Discovery. The third mate, Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton, RNR, was sent to Aldershot for a short ballooning course. In February 1902, at what would later be named Balloon Bight in the Bay of Whales, on the Ross Ice Shelf, a balloon was inflated and anchored by a wire pegged into the ice. Shackleton assumed that he would be the first Antarctic aeronaut; however, Scott pulled rank and insisted on going up before him. Shackleton went next and ascended to 650 feet (198 metres), from which height he took a number of photographs. Dr Edward Wilson declined the offer of a flight, as he thought it was far too risky an enterprise:

‘Some twenty or thirty hydrogen cylinders were laid near, the fixings attached and the balloon filled. The captain, knowing nothing whatever about the business, insisted on going up first and, through no fault of his own, came back safely. The whole ballooning business seems an exceedingly dangerous amusement. There is one man who is supposed to know all about it, who has had a week’s instruction.’36

A balloon being deployed in Antarctica by members of Captain Scott’s expedition in 1902.

The growth of the Balloon Sections between 1899 and 1901 was marked; with the provision in the Army Estimates rising from three officers, thirty-one NCOs and men, to eight officers, 173 NCOs and men.37 Templer took up his role of superintendent once more in the middle of 1901. In December of that year he travelled to Paris, where, among other luminaries, he met Alberto Santos-Dumont and Colonel Charles Renard. Perhaps inspired by his fellow pioneers he devoted much time and effort over the next few years to promoting the dirigible balloon. His subsequent report to the War Office, dated 2 January 1902, stated:

‘I am of the opinion that we are well ahead of them [the French] in all matters appertaining to captive balloon work. At the same time, the dirigible balloon has now, by the prowess of M. Santos-Dumont, been so advanced that I [shortly] will be in a position to recommend that certain experiments be carried out in dirigible balloon work by this department.’38

The contemporary historian of British military ballooning, Colonel Watson, agreed, writing in 1902:

‘The question of dirigible balloons has to be taken up, as it will never do for England to be left behind in the path of progress. But there is no reason why, if funds can be allotted for the purpose, the Balloon Factory at Aldershot should not produce a dirigible balloon as good, if not better, than that which can be made in any factory on the Continent.’39

The Army Estimates for 1902 contained an enhanced requirement for six Balloon Sections of twelve balloons each, five operational and one cadre. In 1903, the Balloon Sections had 150 officers and men, and thirty-six horses. The commanding officer from April 1903 was Lieutenant Colonel John Capper, CB, RE. As the first field officer in command in peacetime since 1889, his appointment put, ‘new life into the branch’.40 He soon made his mark by recommending that officers and men going aloft should wear kit that was practical and serviceable, with particular reference to the undesirability of belts, revolvers and spurs.41 In June, he was also appointed as Secretary to the new Committee on Military Ballooning, which had the remit of reporting generally upon, ‘the extent to which it is desirable to attempt to improve and develop military ballooning’, bearing in mind the recent operational experience and also taking account of progress in other countries. One of the members of the committee was Brevet Lieutenant Colonel H.H. Wilson, DSO, (1864–1922) who was born in Co Longford and would later, as Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, be assassinated by the IRA.

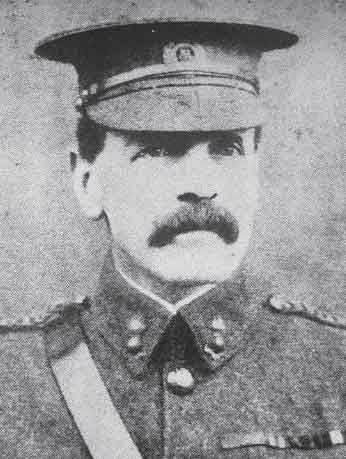

Lieutenant Colonel John Capper.

The committee interviewed some of the balloon officers who had served in South Africa and representatives of the artillery. Three senior officers spoke warmly of the aeronauts’ contribution, Lieutenant General Lord Methuen, Major General A.H. Paget and Rear Admiral H. Lambton (who had been responsible for the naval gunners at Ladysmith). Progress in the rest of the world was surveyed and it was noted that while there had been ongoing research in France, a dirigible had not been produced at Chalais-Meudon since La France in 1884; the expertise in Germany with regard to kite balloons was considered, though no mention was made of Count Zeppelin.

The Rise of the Zeppelin

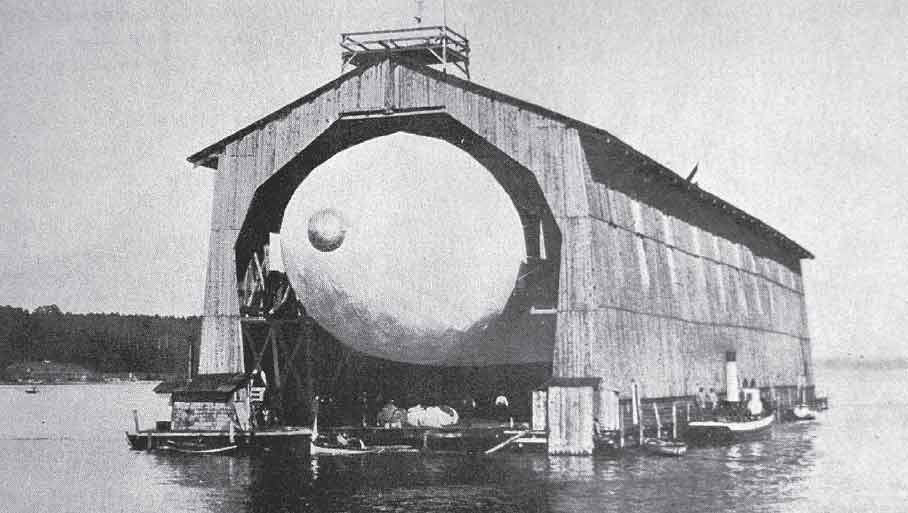

The first flight of the LZ1 rigid airship, which was 420 feet (128 metres) in length, 38 feet (11.54 metres) in diameter, with a capacity of 400,000 cubic feet (11,320 cubic metres), developed by the now-retired German army General, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, (based on the original designs of David Schwarz) had taken place on 3 July 1900, from Friedrichshafen near Lake Constance (Bodensee) before a crowd of 12,000 spectators. Construction had begun some two years earlier in June 1898 in a hangar resting on ninety-five floats on the lake. It was a quite revolutionary engineering concept on a massive scale, a rigid structure of vertical rings held in place by longitudinal girders, with bags or cells containing hydrogen suspended within the framework under its fabric outer cover. Over the next few months it made two more flights, only one of which could be said to have been very successful. The LZ1 was a crude, heavy design, which could lift a payload of just 660lbs (299kg), and which was difficult to control and manoeuvre. The sliding weight in its keel for trimming the airship in flight was a particularly ponderous conception. A newspaper reporter commented that all von Zeppelin’s ideas:

‘While extremely interesting, have undoubtedly proved conclusively that a dirigible balloon is of practically no value.’42

LZ1 in its shed on Lake Constance.

Dr Hugo Eckener (1868–1954), who would later have a huge role to play in the Zeppelin story, was a little more positive in his report for the Frankfurter Zeitung about the second flight on 2 October:

‘Amid cheers, it rose calmly and majestically into the air. It hovered over the lake, making small turns about its vertical axis. It also turned slightly about its horizontal axis, remaining steady and calm, always at the same height and above the same place. There was no question of the airship flying for any appreciable distance, or hovering at various altitudes. One had the feeling that they were very happy to balance up there so nicely.’43

Sadly for the Count, after one further flight, with all his funds exhausted, the LZ1 was grounded and dismantled. Its top speed had been just over 19mph (32kph). The concept of a rigid airship had been proved workable, but further development was needed to make it a practical aerial vehicle.

Other Dirigibles

Privately funded experiments with small non-rigid dirigibles had achieved a degree of success in France, and indeed England. On 19 October 1901, the Brazilian, Alberto Santos-Dumont (1873–1932), and his small airship No 6, flew from Saint-Cloud, circled the Eiffel Tower and returned whence it came in under thirty minutes to win a prize of 100,000 francs offered by M Deutsch de la Meurthe of the Aéro-Club de France. Santos-Dumont and his series of fourteen small designs can truly be said to be the first practicable non-rigid airships. Later, he worried about the non-peaceful use of airships, envisaging, ‘aerial chariots of a foe descending upon England’.44 He also predicted that the airship would be used for observing submarines below the surface of the sea and that they might drop ‘dynamite arrows’ on them.45 Further progress was made by Paul and Pierre Lebaudy, together with the engineer Henri Julliot, whose first airship, the eponymous Lebaudy, took to the air on 13 November 1902, and a year later made the world’s first cross-country flight by dirigible of 38 miles (62 kilometres), from Moisson to the Champs-de-Mars in Paris.

Santos-Dumont and his first dirigible in Paris, 1898.

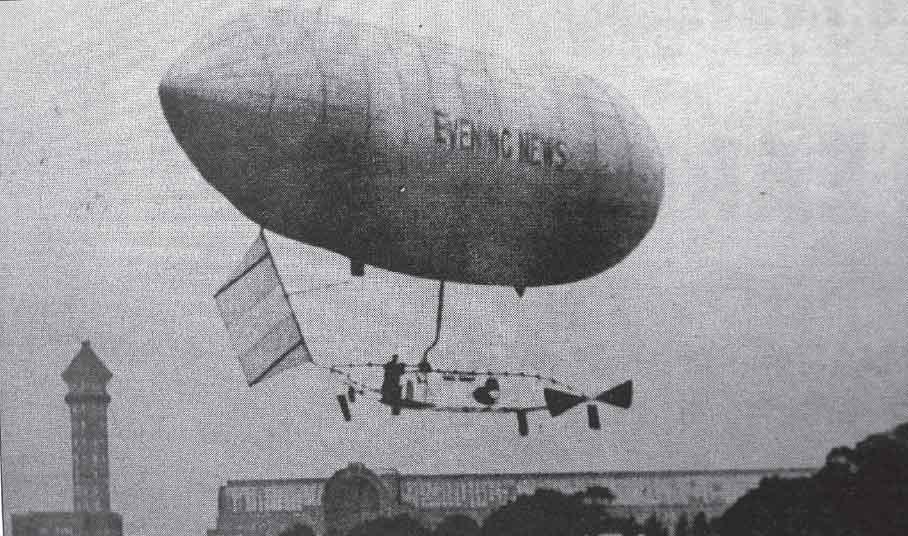

In 1902 came the first navigable flight in the UK by an airship, made by Stanley Spencer at Crystal Palace on 22 September. He landed safely after an hour and forty minutes in the air. It was 75 feet (23 metres) long, with a diameter of 20 feet (6 metres) and a capacity of 20,000 cubic feet (566 cubic metres). The engine was a water-cooled 3 hp (2.22 kW) Sims with a propeller of 10 feet (3 metres) in diameter. The motive power was very low and the airship could progress at a very slow rate only, and had great difficulty making any headway against even a slight wind.

It may therefore be considered that the Committee on Military Ballooning should have widened its scope somewhat and not just examined other governmental establishments. However, detailed recommendations were made as regards the future organisation of the Balloon Sections, Balloon School and Balloon Factory. It was proposed that the latter should be re-sited to a location which would allow greater room for expansion – early possibilities which were considered included sites in the vicinity of Northampton and Rugby. Research and development objectives were identified: a dirigible balloon, an elongated balloon, man-lifting kites, small signal balloons, a mechanical winch to haul down balloons, and photographic equipment. One of the most difficult problems which it debated concerned the major weaknesses of the spherical balloon – its tendency to wobble and rotate at the end of its tether, so causing a certain amount of motion-induced sickness to the occupants, and the limitations this imposed on accurate observation as it made it rather difficult for the observer to hold his binoculars still; a wind speed of greater than 20mph (32kph) so exacerbated these that any useful work from the balloon was all but impossible. The committee’s final report was submitted on 4 January 1904. It has been described as, ‘the most comprehensive review of military aviation’ made to that date.46

The Stanley Spencer airship at Crystal Palace on 22 September 1902. (via Nick Forder)

It should also be considered in the light of another historian’s comment that:

‘By 1900, education, experience and environment, had created a ruling caste [in England] whose knowledge of the revolution then taking place in armaments was limited. A very long period of peace and prosperity was ending. The Boer War announced the need to change from a colonial to a world-wide strategic concept.’47

Farnborough – the cradle of British Military Aviation

The new location selected was Farnborough Common, a few miles up the road from Aldershot. (This move heralded the start of a process whereby a small town in Hampshire, just outside Surrey and close to the border with Berkshire, would become one of the most renowned centres for aeronautical experiment, testing and development in the world.) A few months later Colonel Templer received a welcome boost, as his salary was increased to £900 a year. His worth was underlined in a letter to the War Office from Major General W.T. Shone, the Inspector General of Fortifications:

‘We cannot afford at the present time to lose the services of Colonel Templer, and I would invite attention to the large sums now expended by France and Germany in endeavouring to manufacture a satisfactory dirigible.’48

He was also described by ‘The World’s First Air Correspondent’, Harry Harper of the Daily Mail, as, ‘a burly, genial figure with a walrus moustache.’49

The Treasury allocated the sum of £2000 to build an airship for the army; upon which Templer started work in respect of manufacturing an elongated envelope from goldbeater’s skin, and investigating the design and construction of a suitable engine. To assist with familiarising some of his officers and men with the internal combustion engine, Templer bought two second-hand motor cars. These proved highly popular with foxhunting Royal Engineers, as they now had a free means of transport to their meets.50 He also paid another visit to Colonel Renard at Chalais-Meudon, where he discovered the French Government was apparently allocating between £25,000 and £30,000 to the activities of the establishment.51 Back at Aldershot, two envelopes had been prepared by 1904 and tests were carried out with regard to gas retention, which used up all the available funds and so work ground to a halt. The move from Aldershot to Farnborough, while it would prove beneficial in the long run, did not, of course, serve to speed up work in hand while the transfer of location was being carried out, nor indeed would the change of command from Templer to Capper.

A flavour of life with the Balloon Section in those days may be gained from the autobiography of F.M. Sykes, who, at that time, 1904, was a 27-year-old lieutenant in the 15th Hussars. (Air Vice-Marshal Sir Frederick Sykes (1877–1954) would become an important figure in British aviation and was later described in glowing terms by Murray Sueter in his book, Airmen or Noahs; ‘The Military Wing, RFC, owed much to Sykes’ great abilities. He was a hard worker and bore much of the burden in those difficult times in creating a military air service for the army, which is slightly less conservative than the navy.’) By permission of Colonel Capper, he was attached to the Balloon Camp for a period, under the command of Lieutenant P.W.L. Broke-Smith at Bulford, and then attended a course at Farnborough. He first flew in a very small balloon of only 4500 cubic feet (127 cubic metres) capacity. In fact it could not even lift a basket, so Sykes was taken up to 200 feet (61 metres) in a net suspended from the gasbag. He recalled:

‘We had an exciting time with the various types of balloons on fielddays. We tried experiments in raising and lowering a balloon while on the move with an observer in the car, both forward, backward and laterally, so as to render it as difficult as possible for the envelope to be hit by gunfire. Sometimes, in favourable conditions, we managed to attain an elevation of 1300 feet (396 metres) with two of us in the car, and gained a splendid view of many miles in all directions. With one of us alone, a height of 1600 feet (487 metres) was achieved, and various methods of signalling were tried.’52

Filling a balloon at Aldershot in 1903.

Sir Frederick Sykes.

Captain P.L. Broke-Smith.

As the balloons were all spherical in shape, they had a marked tendency to oscillate in the wind in such a way as to promote motion sickness in some of the aeronauts, but not Sykes:

‘When the balloon was fairly steady one could sketch the country with considerable accuracy, and in addition we did a lot of photographic work, and also practised telephoning from the air to headquarters.’53

Free-trailing was popular as a diversion, lowering a hemp rope and dragging it across the ground to keep the balloon at more or less an even height – though:

‘Crossing telegraph wires and woods led to considerable complications, as we were completely at the mercy of the wind and a change of direction occurred at every few hundred yards.’54

Other exciting pastimes included:

‘Pleasant but chilly night ascents, but the most enjoyable and instructive experiences were on free runs. The stillness and serenity of moving as a part of the wind at a great height above the earth gave pure delight.’55

The experience, though enchanting, was not without its perils:

‘A sudden change of temperature often caused a balloon to descend with such velocity that it became necessary to expend much ballast to avoid being entangled in trees, hitting houses, or (in open ground) getting severe bumps. On one occasion we only escaped a collision with a passing train by letting out an extravagant amount of ballast.’56

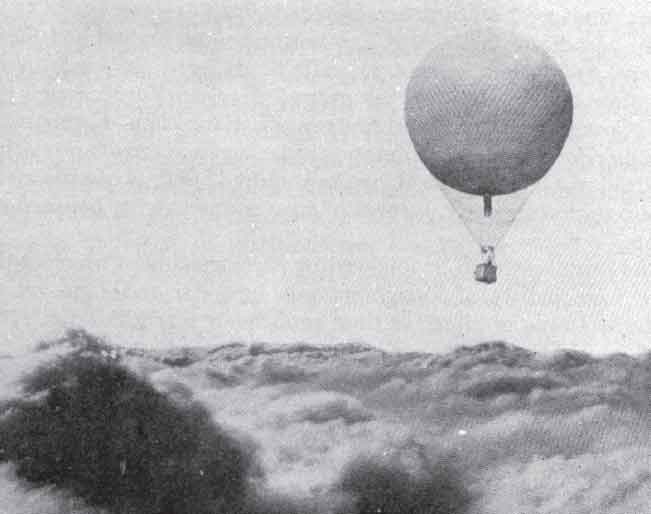

A free balloon above the clouds.

Sykes believed that flying had a great future for both military and civil use, which was strengthened by: ‘The practical experience of ballooning, the only form of aeronautics then in existence in England.’57

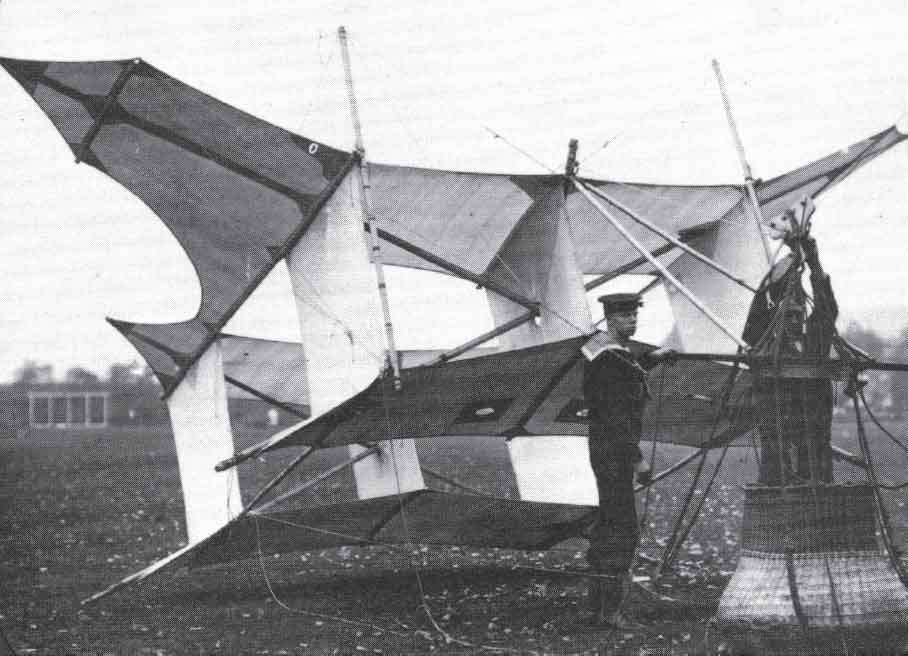

This was not strictly accurate, as man-lifting kiting was also practised under the flamboyant S.F. Cody. One of the aeronauts regularly taken aloft was Lieutenant Broke-Smith, describing it as:

‘Reliable in practice to lift an observer to a height of 1500 feet above the ground, which was the normal balloon observation height and which could be operated in winds of 20–50mph. Reports could be made by telephone or message bag and the same cable, observer’s car or basket, and limbered winch wagon, could be used for both kiting and ballooning. A drill was evolved, and the kites could be set up and flown in less than the twenty minutes taken to fill and put up a balloon.’58

The intrepid Broke-Smith, on at least one occasion in 1905, was raised to a height of 3500 feet (1060 metres) by this means.

Observation from the air was starting to be regarded as a necessary component of the order of battle. Balloons had proved their usefulness, but they were either tethered or were taken to wherever the wind blew them. Moreover, they were large, round targets for enemy guns. A balloon also took a long time to unpack, inflate, launch, recover, deflate and stow away on its wagon. About eight wagons were needed to transport a balloon company – which the sections had been renamed in 1905. These were usually horse drawn, though motive power was sometimes provided by traction engines.

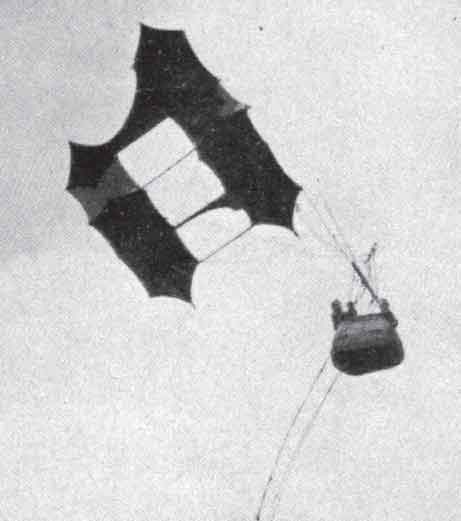

A Cody man-lifting kite.

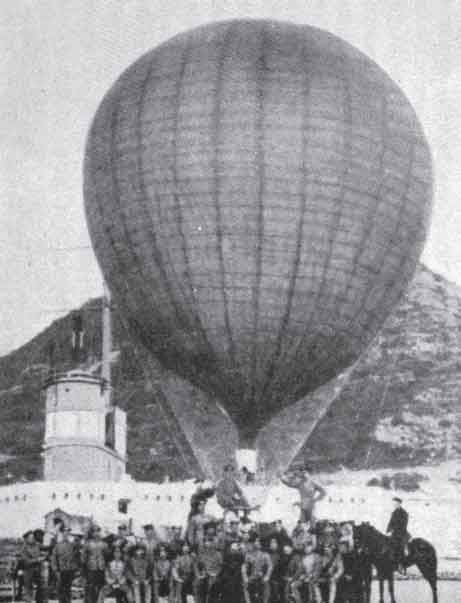

By 1905, the old Balloon Shed had been dismantled and re-erected at Farnborough, a new large airship shed had been constructed, as well as a substantial main workshops building and a hydrogen plant. Over the next few years, the work of the Balloon Factory included investigations into man-lifting kites, photography, signalling between ground and balloons, petrol motors, elongated balloons and mechanical towing machinery. Experimental work was carried out at Gibraltar and Malta to examine the possibility of using balloons in spotting submarines and mines. The Gibraltar detachment, commanded by Lieutenant G.F. Wells, RE, conducted trials with a balloon operating off a destroyer. Due to the difficulties encountered with the weather, and its effect on the stability of the balloon at speeds in excess of 25mph (40kph), it was not judged a great success.

2nd Balloon Section at Gibraltar, 1904.

Willows No 1, Splott, Cardiff, on 18 August 1905. (Via Ces Mowthorpe)

Airship activity was not confined to the Balloon Factory. The first of several successful airships constructed by Ernest Willows (1886–1926), which was 72 feet (22 metres) in length, had a diameter of 18 feet (5.5 metres) and a capacity of 12,000 cubic feet (340 cubic metres), first flew on 5 September 1905, near Cardiff, powered by a 7 hp (5.18 kW) Peugeot motorcycle engine driving a propeller aft, measuring 10 feet (3 metres) in diameter, but with two further steering propellers on swivelling mounts in the nose of the triangular keel. Willows believed that the ability to direct the passage of an airship accurately was of the utmost importance and his work with steering propellers was based on the previous ideas of Captain William Beedle. During the course of its maiden flight, which lasted an hour and twenty-five minutes, Willow’s airship attained a height of 120 feet (36 metres).

In April 1906, the Balloon Companies were absorbed by the Balloon School under Colonel Capper as Commandant, who was also appointed Superintendent of the Balloon Factory from May 1906, with a total salary of £944 a year. Capper had been a Brevet Lieutenant Colonel since 1900, being appointed to substantive rank in October 1905, with further brevet promotion to full colonel in January 1906. Capper was noted as a rigid disciplinarian who had done a good job in reorganising the Balloon Sections. He inspired loyalty and respect, and was capable of personal kindnesses to his men off parade. He was, however, much less accomplished than Templer as regards scientific and mechanical engineering knowledge. Templer retired as superintendent in 1906, but was retained for a further two years as Consultant Engineer on the development of the dirigible, at a fee of £300 per annum plus his retired pay. Templer (1846–1924) deserves to be remembered as one of the seminal figures in British aviation history. Capper praised his enthusiasm, boundless energy, optimism in the face of setbacks, kindness and dogged determination to overcome all obstacles placed in his path by his official superiors. He noted that Templer was not always popular with senior officers due to his disregard of regulations and bureaucracy, but in the end usually managed to get his own way and convince them he was right. It would appear that he fell foul in some way of Lieutenant General Sir John French, the C-in-C of Aldershot Command. A letter from French, of 19 October 1905, shows that he did not regard Templer highly as an administrator and that he had something of a prejudice against non-regular officers holding executive positions.59 An unorthodox financial arrangement made by Templer’s clerk, Warrant Officer Jolly, with a private company regarding the sale of surplus oxygen, did nothing to improve Lieutenant General French’s humour.60

The Army’s future in the air could have been considerably enhanced if a venture undertaken by Capper in December 1904 had met with official approval. While in the USA attending the World’s Fair Exhibition in St Louis on behalf of the War Office, he had taken the opportunity to visit the Wright brothers at Dayton.61 (Orville Wright’s historic first flight of 17 December 1903 was described in the Daily Mail as having been made by a balloon-less airship.) They had just finished flying for the season, having progressed to flights of five minutes duration. Quite informally and without authority, Capper sounded out the brothers with regard to coming to England and working for the War Office. They responded that in return for a hefty fee, £20,000, they would be prepared to work solely for the British Government for four years. This sum represented about twice the yearly budget allocated by the War Office at that time for ballooning. Back in England, Capper very strongly recommended that this proposal should be taken up; negotiations did in fact take place over the next year and more, but no agreement was reached.62 Capper wrote in his report:

‘At least [the Wright Brothers] made far greater strides in the evolution of the flying machine than any of their predecessors. The work they are doing is of very great importance, as it means that if carried to a successful issue, we may shortly have, as accessories of warfare, scouting machines which will go at great pace, and be independent of obstacles of ground, whilst offering from their elevated position, unrivalled opportunities of ascertaining what is occurring in the heart of an enemy’s country.’63

Interestingly, the Secretary of State for War, R.B. Haldane, who served in that position between 1905 and 1912, was of the opinion that the Wrights were not scientific enough in their approach to solving the challenge of sustained, powered flight. He regarded them as clever empiricists.64 Haldane, a very able Liberal Imperialist, was noted for his arrogance and smoothness, which considerably irritated his political opponents.65 (Richard Burdon Haldane (1856–1928), held ministerial office in both Liberal and Labour administrations. In a recent book he has been described as one of Britain’s ablest war ministers, whose greatest political gift was a willingness to listen to professional advice, distil the best and facilitate its implementation.)

Neville Usborne’s career between 1903 and 1908

On 15 March 1903, Neville Usborne was promoted to Lieutenant RN. He joined HMS Thames to enter the nascent submarine service on 24 June 1903. This was a Mersey Class 2nd class cruiser of 4050 tons launched in 1885. She was converted to a submarine depot ship in 1903. The Thames was fitted as a floating workshop, and was moored with the powder and quarantine hulks high in Fareham Creek, Portsmouth, because submarines were a new and uncertain weapon – HM Submarine No 1 had been launched only a few months before on 2 November 1902. It would appear that the underwater life was not appealing, as Usborne left the submarine service in 1904 to serve – from February 1904 to August 1904 – in HMS Doris, one of a class of nine 2nd class cruisers of 5600 tons built between 1894 and 1896. His commanding officer reported that he was, ‘a capable, zealous and hard-working officer.’66 Additionally, the written approbation of their Lordships of the Admiralty was expressed for two reports submitted by Usborne on the defences of Lisbon and of Palma, Majorca.67 It is interesting – but inconclusive – to note that HMS Doris was one of four Royal Navy ships supplied in 1903 with a set of Samuel Cody’s man-lifting kites; pilot kite, two lifters and a carrier with controls and a basket, and intended to be launched and towed behind a ship for the purposes of reconnaissance, signalling, spotting the fall of shot, or of elevating wireless aerials.68 (The other vessels supplied with kiting apparatus were the battleships HMS Majestic and HMS Revenge, and the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope. Officers and men from the four ships undertook instructions in London in the use of the kites.) No records remain to show if Doris used the kiting apparatus while Usborne was a member of the crew, but if this was the case then it may well have stimulated his interest in the possibilities of aviation.69

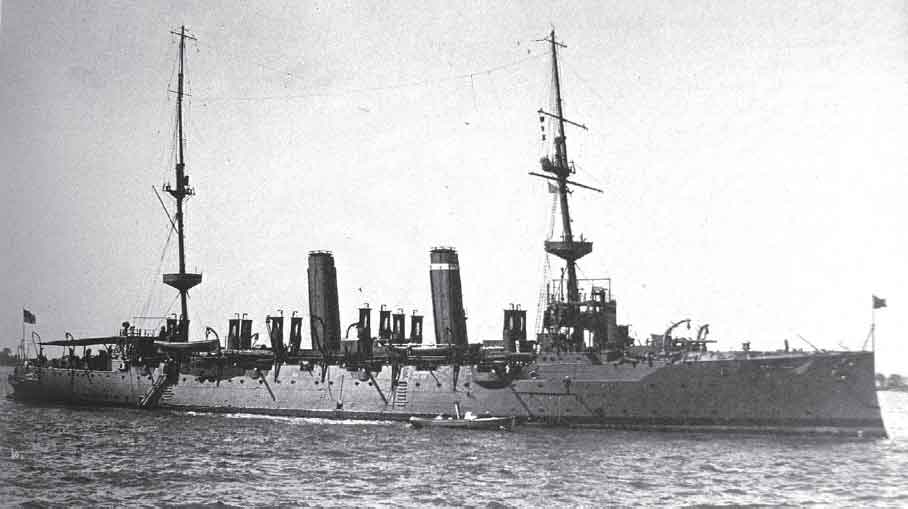

Neville served in HMS Doris in 1904.

In August 1904, approval was given for six months leave to go abroad to study German, during which time he was placed on the books of HMS Firequeen, the Portsmouth depot ship.70

Having been selected for qualification as a Lieutenant (T), March 1905 found Usborne at HMS Vernon, the RN torpedo school in Portsmouth, where the pioneer ironclad Warrior had arrived in 1904 as a floating workshop, power plant and wireless telegraphy school. In May 1905, he added to his skill at French (for his proficiency in this language he had been awarded the Ryder Memorial Prize as the best student of his year) with the attainment of Interpreter (Higher Standard) in German, for which a gratuity of £70 was granted. In August 1905 he gained a further note of their Lordships’ approval for his services as an interpreter during a visit from the French fleet.71 From July 1905 to April 1906 he was a Lieutenant (T) under training in HMS Defiance and was again described as, ‘zealous and hard working.’72

This was a ninety-one gun screw vessel of 5700 tons, the last RN wooden line-of-battle ship, launched at Pembroke in 1861. She became the Navy’s torpedo school ship in 1884 and was sold in 1931. While serving there Usborne once more came to their Lordships’ attention, being praised for the experiments he carried out in connection with wireless telegraphy.73

From April 1906 to March 1907, he attended the Junior Staff Course at the RN College Greenwich. While there he was awarded the Trench-Gascoigne 2nd Prize of thirty guineas by the United Services Institution for an essay on a naval subject. For this he wrote a closely argued and technically detailed piece which was titled; ‘What is the relative value of speed and armament, both strategically and tactically, in a modern battleship, and how far should either be sacrificed to the other in the ideal ship?’ The RN’s most likely probable enemy was identified as the German Navy and the factor governing the relative strengths of the two was stated as the amount of money each was prepared to spend. Usborne writes with clarity and lucidity, and supports his points with a judicious use of statistical evidence and graphical presentation. He concludes that the British fleet should aim for a policy of gradual growth, keeping well ahead of possible opponents in the matter of speed, but without in any way sacrificing gun power to this necessity. It is obvious from reading Usborne’s words that he takes his profession seriously and is studying technical, tactical, strategic and political matters with interest.

Having qualified for Lieutenant (T), from April 1907 to June 1907, he served in HMS Actaeon – the shore establishment for torpedo training at Sheerness, its nucleus being the former twenty-six gun steam frigate Ariadne of 4538 tons and was rated, ‘a very capable torpedo officer.’74

In March 1907, it would appear that an interest in aviation had developed, as he wrote to the Admiralty requesting that he might be noted for employment in connection with aerial navigation work should anything for officers arise in the future.75 While awaiting something suitable, Usborne continued with his specialisation. From June 1907 to September 1908, he served as Lieutenant (T) in the County Class cruiser, HMS Berwick, of 9800 tons, launched in 1902, and was once more praised in his CO’s report: ‘A most able torpedo officer. Very zealous and hard-working. Has the knack of handling men.’76

Neville served in HMS Berwick from 1907 to 1908.

As part of his duties he would have been in charge of much of the ship’s electrical fittings, therefore it may be assumed that he was developing and gaining in technical knowledge all the time. His skill as an interpreter proved useful once more during 1907, when he was again thanked for services rendered during the visit of the German cruiser, SMS Scharnhorst. He subsequently wrote a report on the wireless telegraphy equipment of the German vessels, for which he was praised.77 Further evidence of his desire to be involved in aviation may be seen in the application which he made in August 1908 to undertake the Army Balloon Course. This was approved, subject to a place being available on a course commencing after September 1908.78

Reports have survived of a Lieutenant Usborne being in charge of the Royal Navy’s further experiments with Cody kites at Whale Island, Portsmouth, between August and October 1908.79 However, the reports on the trials were not signed by Neville, but by his brother Cecil Vivian. They took place ashore and in a variety of warships, including the battleship HMS Revenge, the cruiser HMS Grafton, and the torpedo boat destroyers HMS Fervent and HMS Recruit. Harry Harper recorded that Cody, ‘astonished the officers of that vessel by striding up their gangway in full cowboy attire, complete with an enormous ten-gallon hat.’80 Usborne was taken aloft on more than one occasion, reporting that from a height of 1200 feet, he had a good bird’s-eye view of Portsmouth Harbour, Portsdown Hills and the Isle of Wight. Exercises were also conducted with submarines and experiments with photography were made.81 Despite favourable reports from Lieutenant Usborne, Captain Tupper of HMS Excellent and the Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, Admiral Fanshawe, the Admiralty decided to proceed no further with naval kiting in his reply to the C-in-C of 24 December 1908.82

A Naval kite being prepared for flight at HMS Excellent in 1908.

It seems more than likely, given Neville’s already stated interest in aviation, that he would have talked over progress or otherwise at Whale Island with his brother. Family matters were not overlooked, as in December 1908; he was the best man at Vivian’s wedding, which took place in St Margaret’s Church, Westminster.

Dreadnoughts and Submarines

In October 1906, HMS Dreadnought was completed, having been built in just one year. With her revolutionary heavy armament and steam turbines, Dreadnought rendered all her contemporaries obsolete. Caught napping, Imperial Germany would respond in due course with dreadnoughts of her own.

In December of the same year, SM U-1, the first German U-boat, was commissioned into the Imperial German Navy. The Royal Navy was also building up its submarine service with the B, C and D classes being designed, built, and commissioned between 1905 and 1910, each an improvement on its predecessor.