The ‘Golden Age’ before August 1914

Naval Aviation Career before the First World War

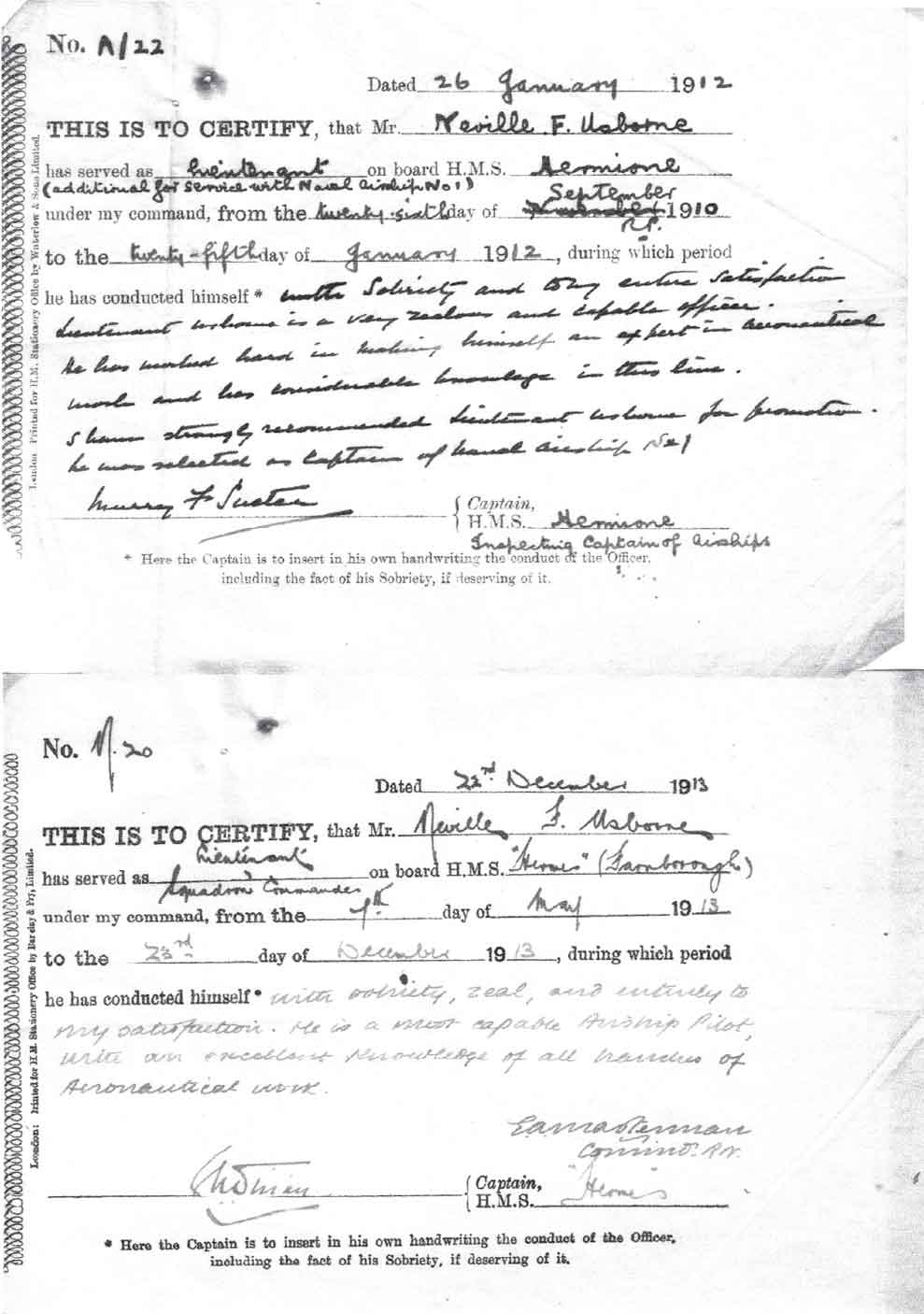

Towards the end of 1908, or the start of 1909, Neville was appointed for work at Barrow-in-Furness in connection with construction of Naval Airship No 1. An entry in his naval record of service notes he was on the books of HMS Vernon for further torpedo qualifications, but also seconded to the Admiralty for special services in connection with airship construction and also for duties as an interpreter in German.1

The first indication of any serious interest being taken in aviation by the Admiralty was on 21 July 1908, when Captain R.H.S. Bacon2, CVO, DSO, RN, the Director of Naval Ordnance, submitted proposals to the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher3, GCB, GCVO, ADC, suggesting that a Naval Air Assistant be appointed, that the War Office should be asked to place the Superintendent of the Balloon School in contact with the Admiralty and that a rigid type of airship should be built for the Royal Navy.4

On 14 August 1908, a letter from the Admiralty invited Messrs Vickers, Son & Maxim of Barrow (Which, as part of BAE Systems, is still to this day a major contractor for UK Government armament work.) to tender for a rigid airship comparable to, or better than, current German airships. There is no doubt that Usborne would have been aware of the developments in lighter-than-air aviation over the previous decade, and that his skills in German would have been most useful in reading material written in the German technical and aviation press.

Progress in Germany

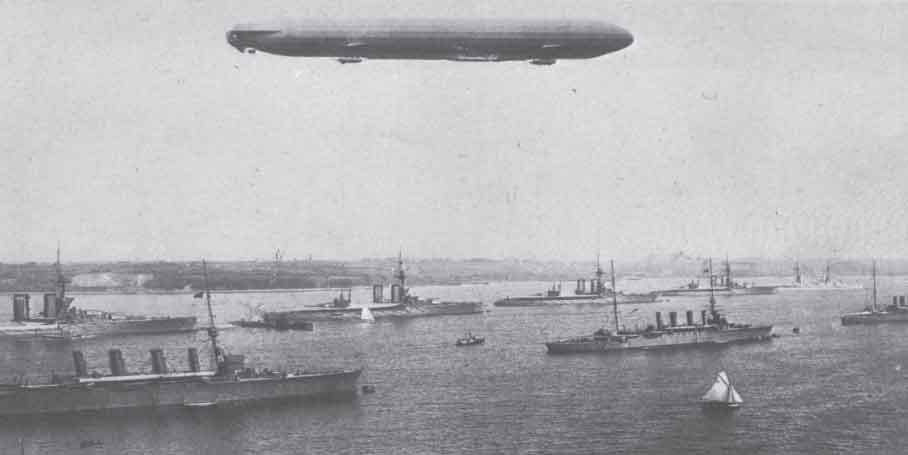

The reconstituted design and production team at Friedrichshafen had suffered the trials and tribulations associated with the development of any new technology. It is of interest to note that British official interest had been aroused, as in December 1905 the British consul in Stuttgart was asked to take note of events at the Zeppelin works.5 The LZ2, which was smaller than the LZ1 and with more powerful engines, crashed on its maiden flight in January 1906 due to uncontrollable pitching movements, engine and steering failure, and was totally wrecked. Sustained flight was achieved with the LZ3 later in that year, which had horizontal stabilisers to cure the problem. Its maiden flight, on 9 October, lasted over two hours, achieving a top speed of 24mph (38kph) with eleven souls on board. In 1907, the Daily Mail’s air correspondent, Harry Harper, who, in 1906, had been appointed the first full-time air correspondent of a national newspaper, reported:

‘Out upon the gleaming surface of Lake Constance the giant craft lies hidden in its floating corrugated iron shed. Count Zeppelin’s crew are at work inside making various changes suggested by successful trials. When they have finished, Count Zeppelin is confident that he will be able to sail for an unbroken period of twenty-four hours. German military experts were jubilant over the Count’s latest achievements and are bringing their utmost influence to bear to induce the government to purchase the ship without waiting for further experiments. Count Zeppelin’s manoeuvres with his airship during the past week have been most remarkable and have convinced everyone that the ship is the most efficient at present in existence.’6

In 1907, at the Second Hague Conference, the declaration prohibiting the dropping of explosives from the air was renewed, but was signed by only twenty-seven of the forty-four powers represented there and of those who would take part as belligerents in the First World War; by Great Britain, the United States, Portugal and Belgium only. The bombardment of undefended places by any means whatever was forbidden. It lapsed automatically in August 1914 and ceased to be binding when non-contracting powers became belligerents. In the meantime it served to concentrate the minds of those in government in Great Britain and would result in the establishment – the following year – of a committee under Lord Esher,7 which will be discussed below.

On 1 July 1908, LZ4 made the first international flight by Zeppelin to Switzerland, overflying Lucerne and Geneva, setting a new world air endurance record of twelve hours. A twenty-four hour flight followed a month later at a time when the longest duration aeroplane flight in Europe was but fifteen minutes. (Though Orville Wright was soon to make a solo flight of an hour and a half in the USA.) Unfortunately, LZ4 came to grief while moored on the ground near Stuttgart. It was destroyed in a gas explosion caused by the build up of static electricity caused by the rubberised cotton gas cells rubbing against each other. Luckily nobody was injured. But from the wreckage emerged a wealth of public support in Germany. Money poured in from the rich and poor, which enabled construction of the LZ5 to begin. On 10 November 1908, Kaiser Wilhelm II came to Friedrichshafen to award the Count with the Prussian Order of the Black Eagle and to declare that he was the greatest German of the new century. In the spring of 1909, LZ5 made a long distance flight of 39 hours and 39 minutes, covering 712 miles (1150 km). The Count had become a national hero:

‘An emblem of German pride, honour and endeavour. Shops sold marzipan Zeppelins, sweets, cigarettes, harmonicas and yachting caps. There were Zeppelin streets, squares, parks, roses and chrysanthemums.’8

More importantly, perhaps, from a practical point of view, the German Army bought LZ3, renaming it SMS (Seiner Majestaet Schiff) Z-I, and LZ5, which became Z-II.9 A little later, in 1909, one of the army airships was flown by Count Zeppelin, Major Sperling, and a crew from the Army Balloon Corps, to Munich, followed by a detachment of cavalry, where she was reported as having dipped her nose three times in salute to the Prince Regent and a huge crowd at the city’s Exhibition Hall, and then onwards over the Royal Palace, from where the Princess Maria Theresa and her daughters waved their handkerchiefs in salutation.10 Soon afterwards, Zeppelin and Parseval airships took part in the Imperial Army manoeuvres, held on the border of Wurtemburg and Bavaria, as also did Krupp’s newly invented anti-aircraft artillery.11

Work progresses at Farnborough under Colonel Capper

Sadly, the first and only fatal accident experienced by British Army free ballooning aeronauts occurred on 25 May 1907. King Edward VII and Prince Fushimi of Japan visited the Balloon Factory to witness a demonstration of free ballooning. The balloon, Thrasher, carrying Lieutenants T.E. Martin-Leake, RE, and W.T.M. Caulfield, RE, ascended and disappeared from view. Over Abbotsbury the two officers called out to a local farmer to catch hold of the trail rope, but to no avail. It came down in the sea off the Dorset coast near Bridport; neither of the officers were ever found, although the tangled wreck of the balloon was salvaged by a fishing vessel. Meanwhile, the Royal Party paid a visit to the nearby shed where important work had been progressing. It is believed that while inspecting work therein, the King personally named the bulky and impressive dirigible, Nulli Secundus. [The King’s choice of name for the airship was reported in the highly reputable French aeronautical periodical L’Aérophile: ‘Nulli Secundus tel serait, assure-t-on, le nom donné, sur le désire du roi Edouard VII, au nouveau dirigible Anglais; il suffit à indiquer que l’Angleterre entend bien ne pas demeurer en arrière des nations continentals dans les applications du ballon automobile.’]12

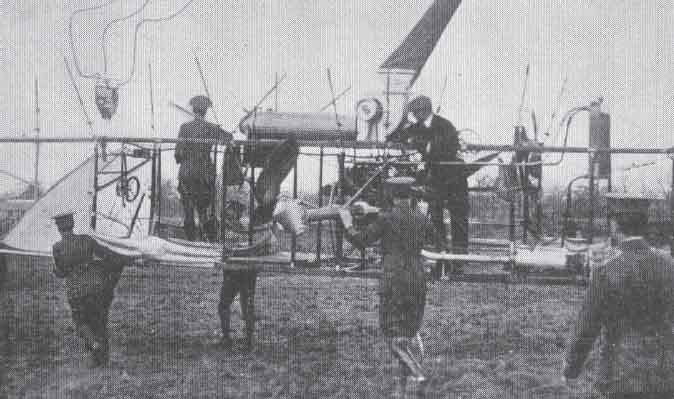

Samuel Cody13 was engaged on the design of the airscrews, engine mounting and the control surfaces for the airship being constructed there. According to Harry Harper, Cody’s, ‘picturesque appearance, and genial, laughing, hail-fellow-well-met manner’ did not endear him to some War Office officials, but more importantly, he and Capper established a rapport and mutual respect.14 A gondola made from a metal tube framework and covered by fabric was constructed by Cody based on plans made by Capper, replacing Templer’s original idea of two basketwork balloon cars. It should be noted that Capper and Templer remained on good terms, and that he made an important contribution to the design of Nulli Secundus, particularly in respect of the construction of the envelope. The challenge facing the team at Farnborough has been described thus:

‘Nulli Secundus I, of course, had more than the usual disadvantages associated with any new and untried airship; not only had both she and her pilot [Capper] never flown before, but the whole design and construction had been carried out by a team that had never produced an airship before.’15

It should, of course, be noted that the same challenge faced nearly every other pioneer of either aeroplanes or airships, including Count Zeppelin, Santos-Dumont and the Wright Brothers, and indeed Harry Ferguson or Lilian Bland in Ireland. Capper tried to rectify his lack of aerial experience by taking part, accompanied at times by Mrs Capper, in a number of civilian balloon events and competitions.

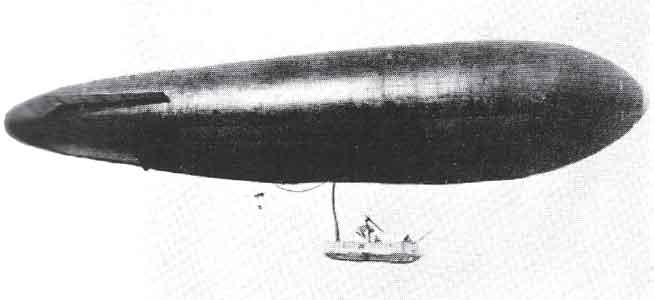

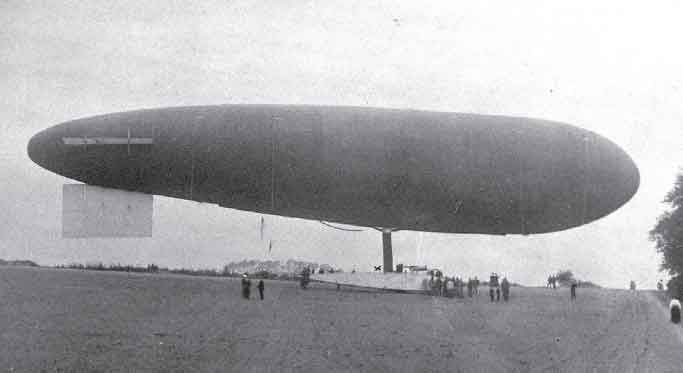

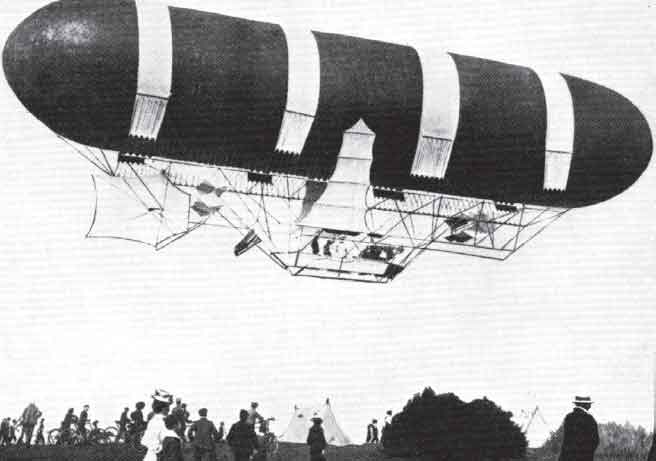

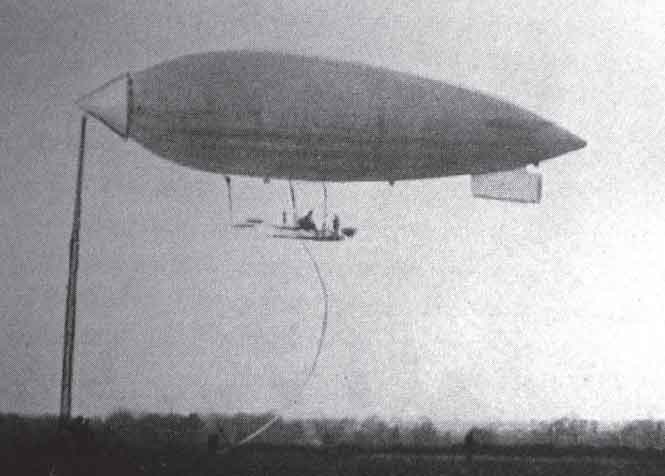

The maiden flight in the brief career of British Army Dirigible No 1, Nulli Secundus, was from the Army Balloon Factory at Farnborough on 10 September 1907. The great shed had been doubled in length to accommodate the airship, which was a brown, sausage-shaped balloon, made from goldbeater’s skin, some 111 feet (34 metres) in length, with a diameter of 18 feet (5.5 metres) and a capacity of 55,000 cubic feet (1556 cubic metres) covered with a net, with the gondola suspended below from a light framework which could hold three crewmen. She was powered by a 40 hp (29.6 kW) Antoinette engine. At first there were a few problems with the engine running hot and generating less power than required to turn the airscrews at a sufficient rate for successful, sustained flight.16 After some adjustments, she undertook a short series of trials with two flights on 10 September, the second of which was witnessed by Colonel Templer and which concluded with a heavier than desirable descent which caused some superficial damage. No further flights took place for the next three weeks as the Balloon School was programmed to take part with balloons and kites in the autumn manoeuvres. The time was spent productively in making structural alterations to the control surfaces. Two trips were made on 30 September and 3 October, which culminated in a circuit as far as Guildford and back. Nulli Secundus had now flown a total of about three hours and a distance of 25 miles (40 kilometres). Capper was determined to influence public opinion and so coerce the War Office into providing greater funding for the development of aviation. It may also have been the case that he was influenced by the success of Zeppelin LZ 3, which had recently made a flight of 200 miles (320 kilometres) in nine and a quarter hours around Lake Constance, and also the French Lebaudy, La Patrie, which, on 12 July 1907, had flown a closed loop of 40 miles (64 kilometres) around Chalais-Meudon, at an average speed of 22mph (35kph). So he determined upon a bold and spectacular flight. On 5 October, Nulli Secundus was flown the 50 miles (80 kilometres) to London in three and a half hours with Capper at the helm, Cody tending the engine and Captain W.A. King, the instructor in ballooning and map-reading, flying over Kensington, Hyde Park and the War Office, circling St Paul’s Cathedral and landing on the cycle track at Crystal Palace, so establishing a new endurance record for non-rigid airships and ensuring huge headlines in the daily papers. Harry Harper reported on the momentous event as follows:

‘In the streets, trams and all other vehicles came to an abrupt halt. London’s millions just stood staring up into the sky in amazement as the airship flew low, only 500 to 600 feet above streets and houses. It was so low that people looking up could see Cody and Capper quite clearly in their small control car, and every now and then Cody would turn from his engine to lean over the side of the car and wave to those below. On the roof of the War Office members of the Army Council stood waving handkerchiefs. It was a moment of triumph.’17

Nulli Secundus I takes to the air on 10 September 1907.

Nulli Secundus I over St Paul’s on 5 October 1907.

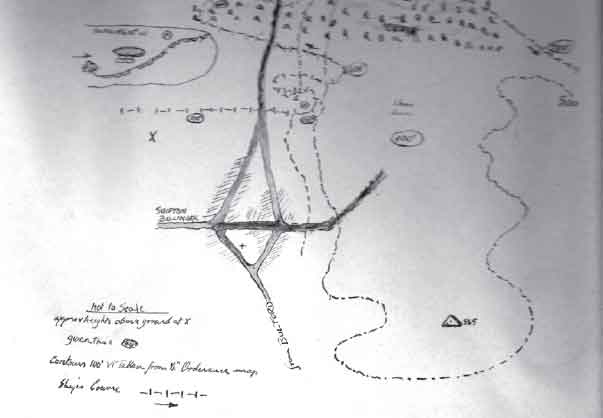

[Author’s note: Nulli Secundus took off from Farnborough at 10.40 am and followed the course Frimley – Bagshot – Sunningdale – Staines – Hounslow – Brentford, at a height of between 750 and 1300 feet (230–430 metres) and an average speed, with a following wind, of 24mph (40kph). She passed over Kensington Palace, Hyde Park, Buckingham Palace, Whitehall, Trafalgar Square, The Strand and Fleet Street, circling St Paul’s at about 12.20 pm. From there a course was taken over Blackfriars, Kennington and Clapham Common before alighting at Crystal Palace at 2 pm.]

Capper was pleased with the way the airship had answered the controls and had steered well, both with and into the wind, overcoming the resistance of the strong breeze to make headway.18 They were driven back to Farnborough in Cody’s large touring car, in which Lieutenant Clive Waterlow had followed the airship, along with petrol, tools and the ground crew, an event which Waterlow described with some glee in a letter to his mother.19 (Waterlow had joined the Balloon School as a 2nd Lieutenant on 18 October 1906; he would spend the rest of his life on airships until his untimely and tragic death in an accident at RNAS Cranwell in 1917, at the age of thirty-one.)20 Three days later, owing to heavy winds and rain which had damaged and thoroughly soaked the envelope, as well as lowering the temperature of the hydrogen, so degrading its buoyancy and lift and, despite the innovative use of slipstream from the propellers to assist in drying out the envelope, the airship had to be deflated, and was taken back to Farnborough by means of horse and cart.21

Capper was interviewed after the flight and said that he was very happy with it; the airship had performed well and could have stayed aloft for longer. He decided to terminate the flight because of the deteriorating weather and didn’t want to take risks at a stage when airship development was in its infancy.22

La Patrie was lost on 29 November 1907, blown unmanned from her moorings at Verdun across Northern France, Cornwall and the Irish Sea. Numerous sightings were reported in the Belfast Telegraph, ‘to the consternation of the inhabitants’ of country towns and villages who, ‘gathered in large numbers’ to view the great yellow dirigible pass overhead.23 She struck a hillside on the south side of Belfast Lough at Ballydavey, Holywood, Co Down, losing a propeller in the process, but ascended once more and was last seen off the Isle of Islay speeding into oblivion.24

Lieutenant Clive Waterlow RE.

During the winter of 1907/08 work began on redesigning and rebuilding Nulli Secundus; modifications included the replacement of the covering net by a varnished silk ‘chemise’, a new understructure, the addition of a reserve gasbag, a new car for the crew and engine mounting, alterations to the control and stabilizing surfaces, and a new bow elevator.

In April 1908, Colonel Templer’s contract was not renewed. No longer would his stocky form be seen in the environs of the balloon shed with a snuff-box in one hand and a large coloured handkerchief in the other. A terse file note is all that has survived by way of an official tribute, ‘Colonel Templer’s services were dispensed with from the 1st inst – 27.4.08.’25 He faded away and has never really been given the recognition he deserves as a great pioneer of military aviation.

In November 1907 parts of the Lebaudy airship La Patrie were left on a hillside in Co Down.

Nulli Secundus II.

Nulli Secundus II first flew on the evening of 24 July 1908, and proved to be somewhat unstable and difficult to trim. Two more short flights were made in August, during which a top speed of 22mph (35kph) was reached, but she was of little value and was broken up. At some stage over the summer a party of naval personnel visited Farnborough and received some instruction in airship handling. Colonel Capper later remarked that as far as the airship’s name went it actually came a bad second to the Willows 1A.26

The Times was much more willing to sing the praises of the team, in particular Cody, Capper and Templer, which had reconstructed Nulli Secundus:

‘As is now known there are many airships which have been completed and are under construction. Every new vessel proves more conclusively to the unbiased mind that it is merely a question of time, practice, experiment and general development – especially regarding the construction of a light yet powerful engine – before airships will be sufficiently navigable, even in strong winds and unfavourable weather, to prove of enormous value to every civilised portion of the world. The first trial of the rebuilt Nulli Secundus, which took place on Cove Common last week, should certainly give every Englishman satisfaction that our experiments, though somewhat tardy, are coming to a more successful path and should encourage all who possess either foresight or patriotism or both.’27

The use of new technology also extended to communications, experiments in wireless telegraphy being conducted. The first wireless company of the Royal Engineers was formed in 1907 at Farnborough. Its primary task was to investigate the possibilities of military communication by means of airborne wireless sets and was, therefore, attached to the Balloon School. In May 1908, Capper, and Lieutenant C.J. Ashton RE, ascended in the free balloon Pegasus to a height of 8000 feet and, when aloft over Petersfield, received signals from a wireless station at Aldershot some 20 miles (32 kilometres) away and also from the battleship HMS King Edward VII, which was lying off Portsmouth. The British and Irish press reported in July 1908 that successful experiments had taken place near Berlin, conducted by the German army, concerning the dispatch of wireless telegrams from a dirigible.28 As this technology involved sparks on electrical contacts it was regarded as rather hazardous when in close association with a gasbag full of hydrogen, however the Germans persevered, and within a few months were using airships equipped with wireless sets on army manoeuvres.

Also in 1908, Lieutenant E.M. Maitland – ‘a brilliant, brave and gallant officer, whose personal influence on the officers and men of the Airship Service became legendary, even in his lifetime’29 – made his first parachute jump from a trapeze suspended below a hot-air balloon at Crystal Palace, landing on the roof of a public house, from which encounter he emerged unscathed – but not so the roof.

Contemporary Media Comment

It is interesting to note that in January 1908, Pall Mall magazine featured the first part of a new serial story by H.G. Wells, The War in the Air, which included a highly coloured description of a devastating attack on a fleet of American dreadnought battleships, followed by a ruinous air raid on New York by an armada of German airships:

‘As the airships sailed along they smashed up the city as a child will shatter its cities of brick and card. Below, they left ruins and blazing conflagrations, and heaped and scattered dead; men, women and children mixed together.’30

Authors in France and Germany during this period, such as Emile Driant and Rudolf Martin, also wrote of airships transporting vast armies to attack Russia or Britain and bring death and destruction on a huge scale. Others believed – employing what could only be wishful thinking – that warfare from the air would be so destructive that it would make conflict between the major powers less likely.31

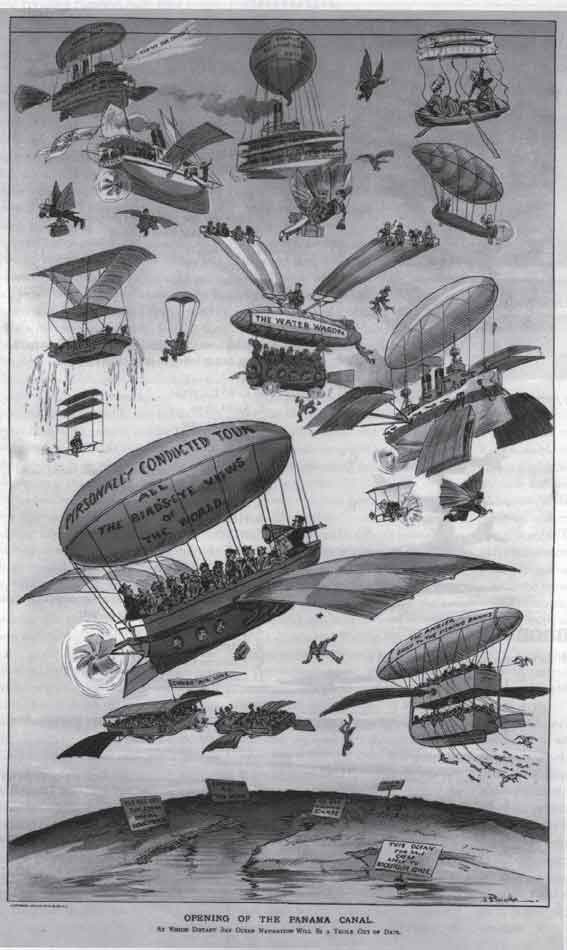

A cartoon from the US magazine Puck of January 1906.

There was a growing sense of public unease that Britain was no longer so securely insulated by the Royal Navy from the threat of invasion. A popular contemporary success in the London theatre was the play, An Englishman’s Home by Guy du Maurier, which showed in dramatic form what might happen if England were subject to a German invasion.

Developments in Government Policy

The potential threat from the air began to shake the populace from its Victorian stance of complacent insularity.32 Indeed, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, made Parliament aware of H.G. Wells’ latest story when participating in the Aerial Navigation Sub-committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence, which had been established in October 1908 with the following terms of reference:

‘Several of the great powers are turning their attention to the question and are spending large sums of money in the development of dirigible balloons and aeroplanes. It is probable that for countries with land frontiers immediately across which lie potential enemies, the development of airships has hitherto been more important than it is for Great Britain, and that we have been justified for this reason in spending less money than some of our neighbours. The success that has attended recent experiments in France, Germany and America has, however, created a new situation which appears to render it advisable that the subject of aerial navigation should be investigated.’33

The Chairman of this sub-committee was Lord Esher, who was not only a distinguished military strategist, but also had the ear and confidence of the King, Edward VII. The other members were the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George; the Secretary of State for War, R.B. Haldane; the First Lord of the Admiralty, Reginald McKenna; the Director of Naval Ordnance, Captain R.H.S. Bacon, RN; the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir W. Nicholson; the Director of Military Operations, Major General J.S. Ewart and the Master General of the Ordnance, Major General C. Hadden. Its aim was to deliberate what should be done about assessing future dangers from the air, how to counter them and how much money to spend on this. Written evidence principally concerning balloons and dirigibles was submitted by Sir Hiram Maxim, Charles Rolls, Lieutenant Colonel John Capper, RE, and Major B.F.S. Baden-Powell. It was decided that airships might well have some utility in the roles of reconnaissance over land and sea, as well as artillery spotting, and that hostile airships might become capable of carrying out bombing raids on the British Isles. From the minutes of the meeting which Colonel Capper attended, it would appear that he lost not only the support of General Nicholson, who strongly disapproved of aircraft of any sort, but also of R.B. Haldane, which did not bode well for the security of his tenure at Farnborough.34 Haldane had been educated in Germany and much admired the inhabitants’ efficiency and technological prowess, being particularly interested in Count Zeppelin’s experiments and progress.35 He was in favour of creating an aerial service, but he wanted progress towards this aim to be structured, measured, organised and systematic, with a scientific research and development programme directed and controlled by the government. Others disagreed and felt that in order not to fall further behind the continental powers, Britain should purchase immediately the latest available technology.36

Figures were released by the War Office in response to a question from Lord Montagu of Beaulieu showing a comparison of the sums spent on aviation in 1908 by several European governments. Leading the field was Germany with £135,000 from public funds, to which was added £265,000 collected by private subscription by the National Zeppelin Airship Fund. Next was France with £47,000, then Austria-Hungary with £5500 and trailing in fourth was Great Britain with £5270, £1980 of which was allocated to the army for dirigible balloons and £3290 on aeroplanes.37 As well as being a distinguished motoring authority, Lord Montagu was very interested in aeronautics and was a founder member of the Aerial League of the British Empire, founded in January 1909. Its aim was to convince the country of the vital importance to the British Empire of aerial supremacy, much in the way that the Royal Navy had assured domination of the seas in the century following Trafalgar. He was particularly exercised by the thought of a fleet of airships striking pre-emptively at the strategic targets concentrated in London, effectively winning a future war before the army or the Royal Navy could get to grips with enemy forces.38

‘It would be possible for dirigibles to leave the frontier stations of at least five Continental powers, all within 500 miles distance from where we are now seated, and do much damage at Aldershot, Portsmouth, Dover, Chatham, Sheerness, and other military and naval stations, without taking into account that an attempt would certainly be made to paralyse the heart of the nation by attacking certain nerve centres in London, the destruction of which would impede or entirely destroy the means of communication by telephone, telegraph, rail and road.

‘Germany’s plans in airships, as in other directions, are not fully known to us; nor would this be the occasion to state how such information can be obtained. But it is beyond doubt that she has, at the present moment, the best and the only fully equipped aerial fleet in the world, and one which is more than a match for all the other dirigibles in existence.

‘The day is not far distant when England will have to be something besides nominal mistress of the seas. She will have to be at least equal to her neighbours in the matter of aerial defence and offence, and it is our business and the duty of the nation at large to see that the authorities are awakened in time to their responsibilities in this direction.’39

Moreover, a very trenchant article in The Times of February 1909 was highly critical of the British efforts so far in the field of aeronautics and argued forcibly for the airship:

‘The war of the future is likely to be decided in no small measure by the use of scientific instruments of destruction controlled by highly trained men. That the airship in its various forms promises to become such an instrument is every day becoming more and more apparent. Progress may be astonishingly rapid, but without well-equipped laboratories, testing grounds and factories, our authorities are utterly unable to discover the merits of new ideas. We are laboriously going over the same preliminary ground which the French and Germans traversed years ago. A most important task is to bring the adult Briton to understand that there is an immediate need for an aerial defence scheme. With this end in view I would favour the holding of public meetings and lectures throughout the important centres and, better still, practical demonstrations by airships, even if we have to go abroad for the machines and the men. It is painful to report that no successful dirigible or aeroplane has yet been flown in the British Isles and that the vast majority of the people have never seen one in any form.’40

A subsequent article in March of the same year contended:

‘In 1912 the Germans will have at least twenty-four mammoth Zeppelin airships, each capable of overseas excursions and probably speedier than any naval vessel. Our rate of production is one vessel per annum and by 1912, at most, we may have some five small-sized, slow, non-rigid airships, which compared to Zeppelins will be as antiquated cruisers to Dreadnoughts. A Zeppelin of the present-day type could reach this country in ten hours and do enormous damage in a brief space of time.’41

Whilst the critique of the British lack of organisation was reasonable enough, the correspondent’s estimate of the German capability was over-egging the pudding somewhat. The somewhat febrile atmosphere was heightened by a rash of reports received in police stations and newspaper offices across the country – in the first few months of 1909 – claiming the sighting of mysterious flying objects, widely believed to be airships of unknown but suspicious origin. This became known as the Phantom Airship Scare and was part of a developing national phobia concerning Germans and their hostile intentions, such as the rumour that there were 80,000 soldiers of the Kaiser embedded in the country, disguised as waiters, barbers, businessmen and shop assistants.42 It was, to a certain extent, a by-product of the Anglo-German naval rivalry and the German desire to have colonies to match those of the British Empire. The paranoia might have been better directed to an appreciation of the portents of firstly, the remarkable feat of Louis Blériot in the early hours of 25 June 1909 when he completed his crossing of the English Channel in his frail monoplane in a time of thirty-seven minutes, and secondly, the International Flying Meeting at Reims a month later, of which it was written:

‘Reims marked the true acceptance of the aeroplane as a practical vehicle and as such was a major milestone in the world’s history.’43

Yet the fixed-wing aeroplane was still in its infancy. David Lloyd George attended the Reims meeting and was impressed by what he witnessed, causing the Morning Post to comment:

‘If Mr Lloyd George’s words help to rouse the minds of his followers to the importance of the question, they will do more for the interests of the country than his stupid abuse of landlords. The Chancellor of the Exchequer says that Englishmen would soon grow enthusiastic if they saw airships in flight. In this he is quite right. As Mr Lloyd George no doubt realizes, it is the dirigible balloon that at present is the best adapted for practical uses. The terrible damage which such a vessel could work, and the tremendous moral effect its operations would produce, render it a most formidable engine of war. An attack could only be effectively met by other airships, and the English people cannot realize too soon the urgent necessity of organizing an aerial fleet. Until this is done the position of the country is one of grave and increasing danger.’44

There was, however, official and military awareness in 1909 of the potential threat posed by German dirigibles. The British Military Attaché in Berlin, Colonel Frederick Trench, had paid particular attention to airship development in the country; questioning his contacts, travelling around the country to view airships, visiting the factories in which they were being constructed, and keeping abreast of reports in the national, regional and technical press. He sent detailed reports to the War Office in London, noting, amongst other events, that a school for aeronauts had been established at Friedrichshafen; secret contracts had been let for the increased manufacture of hydrogen, which would be taken over by the military on the ‘outbreak of hostilities’ and that airship manoeuvres, including wireless telegraphy, bomb dropping and ‘airship chasing’, had taken place in the Rhine Valley near Cologne; which was regarded as being of particular significance as that city was, ‘almost the nearest point to England’.45 Not only did he produce these official reports, but he also wrote privately to Colonel Capper, whom he knew well. He attempted to arrange for Capper to visit Germany to have a look at the dirigibles, but encountered reluctance on the part of previously friendly contacts, which made him even more suspicious of Germany’s ultimate intentions.

Back at Farnborough

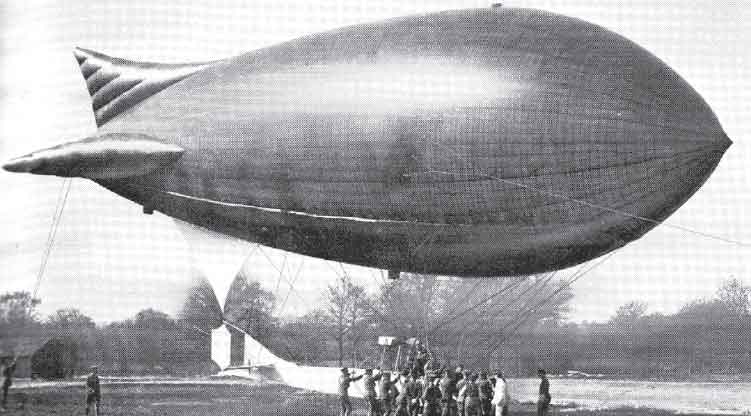

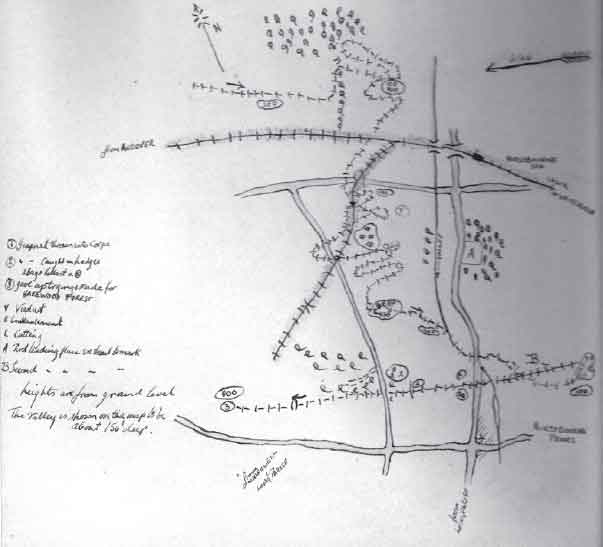

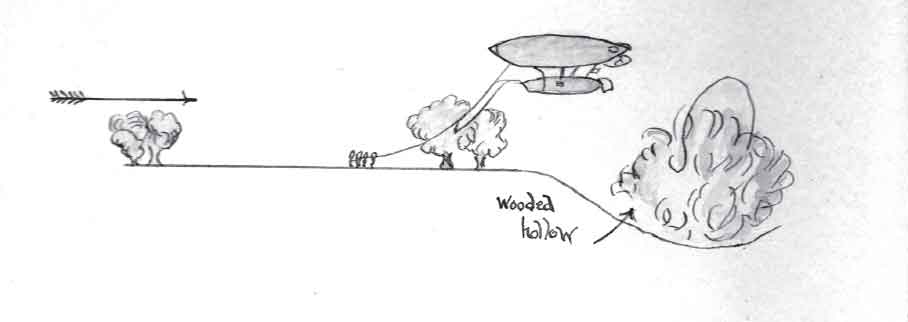

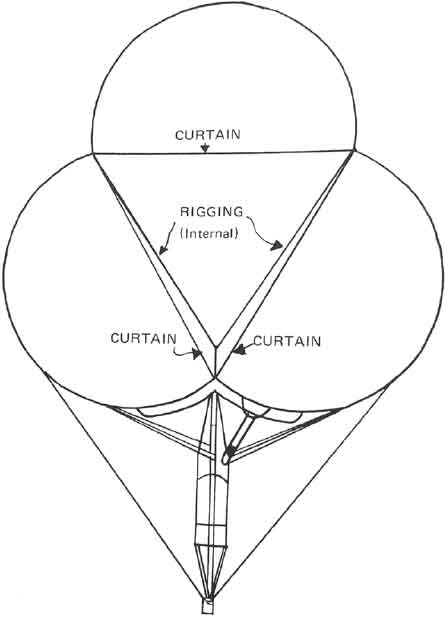

Over the winter of 1908, Colonel Capper and the team at Farnborough had built another non-rigid airship, Dirigible No 2, which made its first appearance in the late spring of 1909 and was unofficially christened Baby. The envelope was fish-shaped, or pisiform,46 to lessen wind resistance as compared to Dirigible No 1 and was made of goldbeater’s skin; she was 84 feet (25 metres) in length and had a diameter of 24 feet (7 metres), with a volume of 21,000 cubic feet (5943 cubic metres). Capper had liaised with the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington with the testing of ebony models of possible envelope shapes in the air channel or wind-tunnel located there, having been told by the Wright brothers of the utility of such a device. One ballonet was contained inside the envelope which, to begin with, had three inflated fins to act as stabilizers. These proved unsatisfactory as they were lacking in rigidity, and were replaced after the first inflation by the ordinary, non-inflatable fixed planes. Two 10 hp (7.4 kW), 3-cylinder Buchet engines were mounted in a long car driving a single propeller, and, at a later date, these were replaced by a 25 hp (18.5 kW) REP radial engine, which was not a great improvement. Finally, a 35 hp engine (25 kW) designed by Gustavus Green was installed. Green (1865–1964) was the first successful aero-engine designer in Great Britain. Over a period of seven months, from 11 May to 10 December 1908, Baby made thirteen fairly short flights with this variety of engines and control surface configurations. This could charitably be described as a development programme based on the trial and error method. She proved to be very unstable and rather slow, barely reaching 20mph (32kph); a complete redesign was required. During the autumn, permission was obtained to enlarge the envelope and fit a more powerful engine.

Baby in May 1909.

Further Official Interest

The establishment of the Advisory Committee on Aeronautics in 1909 was a major step forward, though it had taken all of three years to come to fruition. Early in 1906 a proposal had been made by Colonel J.D. Fullerton, RE, supported by Colonel Templer, for the appointment of a committee consisting of military officers, aeronauts, mechanical engineers and naval representatives to harness the available expertise to investigate all technical matters aeronautical in a structured and scientific fashion. A modified form of this idea was put forward some three years later by R.B. Haldane, the Secretary of State for War. He was particularly keen to involve the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington and thereby, hopefully, bring the best scientific talent to bear upon the study of flight, and give the government direct control of aeronautical research and experiment. (The laboratory was founded in 1900 to carry out scientific tests for theoretical purposes and also for the benefit of British industry, in imitation of, and in somewhat belated response to, the Physikalisch Technichse Reichsanstalt, which had been established in Berlin since 1887. It represented a significant move away from the Victorian laissez faire attitude, which held that industrial activities should be the exclusive pursuit of private enterprise.) A conference was held in the room of the First Lord of the Admiralty and its deliberations were approved by the Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith. The Advisory Committee for Aeronautics was set up with ten members, seven of whom were Fellows of the Royal Society. The President was Lord Rayleigh, OM, FRS and the Chairman, Dr R.T. Glazebrook, FRS, the Director of the National Physical Laboratory. [Lord Rayleigh (1842–1919) was a Nobel Laureate in 1904 and had a worldwide reputation as one of the foremost mathematical and experimental physicists of his day.] The army was represented by Major General Sir Charles Hadden, the navy by Captain R.H.S. Bacon, and the Meteorological Office by Dr W.N. Shaw. Soon, two others were added, Mervyn O’Gorman, when he took over the charge of the Balloon Factory, and ‘the brilliant but unorthodox’,47 ‘difficult and temperamental’,48 Captain Murray Sueter, RN.

Captain Murray Sueter in 1915. (Via Peter Wright)

[Author’s note: Sueter was born in 1872 and, as a junior officer, showed indications of an original mind, and a considerable inventive genius in the new fields of torpedoes, submarines and wireless telegraphy. As the first Director of the Admiralty’s Air Department from 1912 to 1916, he was a tireless advocate of air power and succeeded in annoying many influential senior officers. He was effectively exiled to command in Southern Italy and, following an ill-advised letter to the King in 1917, his active naval career was cut short. After the war, when neither the Admiralty nor the Air Department was prepared to offer a position to this talented maverick, he became a Member of Parliament and a thorn in the side of the establishment. He was, however, knighted in 1934 and lived to a ripe old age, dying in 1960.]

From that time on the National Physical Laboratory worked in very close cooperation with the Balloon Factory. Some of the topics considered, investigated and experimented upon included – air resistance, stresses and strains on materials, means of protecting airships from electrical discharges, the best shape for the wing of an aeroplane and the best fabric for the envelope of an airship. Colonel Capper was a significant omission; despite his obvious knowledge and enthusiasm, he was too outspoken and irascible, and had not impressed Haldane, who considered that he was a clever empiricist but was not the man to build up an Air Service as he envisaged it, on a foundation of science.49

The government’s view of the role of the committee was expressed in the House of Commons. On 20 May 1909, Arthur Balfour asked the Prime Minister about the new committee. Mr Asquith replied:

‘It is not part of the general duty of the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics either to construct or invent. Its function is not to initiate but to consider what is initiated elsewhere, and is referred to it by the executive officers of the navy and army construction departments. The problems which are likely to arise… for solutions are numerous, and it will be the work of the committee to advise on these problems, and to seek their solution by the application of both theoretical and experimental methods of research.’50

The Advisory Committee visited Farnborough on 5 July 1909. No records of what was discussed have survived, but at least early contact was made. It may be considered a weakness that the Advisory Committee was heavily biased towards theoretical knowledge. Where were the industrialists, the engineers, the aviators, who could have assisted with the application of the theory to reality, perhaps by using some of the empiricism so disregarded by Haldane? Writing after the First World War, the official historian approved of Haldane’s methods:

‘These and scores of other problems were systematically and patiently attacked. There were no theatrically quick results, but the work done laid a firm and broad base for all subsequent success. Hasty popular criticism is apt to measure the value of scientific advice by the tale of things done, and to overlook the credit that belongs to it for things prevented. The science of aeronautics in the year 1909 was in a very difficult and uncertain stage of its early development; any mistakes in laying the foundations of a national air force would not only have involved the nation in much useless expense, but would have imperilled the whole structure.’51

In October 1909, the Balloon Factory and Balloon School at South Farnborough, which had been under one control, were separated, with Capper as commandant of the school. The superintendent of the factory appointed, on a salary of £950 a year, was Mervyn Joseph Pius O’Gorman, who became universally known as O’G:

‘A witty Irishman of flamboyant courage and imagination who had already attained eminence as an authority on suction gas engines, and was consultant engineer in the firm of Swinburne, O’Gorman, and Baillie. Sporting a goldrimmed monocle, fiercely brushed-up moustache, long cigarette holder, and immaculate dress, he was, at thirty-eight, a man of brilliant and strong character, he made warm friends as readily as bitter enemies; a thruster with a penetrating outlook founded on degrees in Classics and Science at University College, Dublin, and a post-graduate honours course in electrical engineering at the City and Guilds Institute of London University – yet withal, an artist.’52

Mervyn O’Gorman.

The selection of O’Gorman fitted perfectly with the desire of R.B. Haldane, as expressed in Parliament, to appoint a, ‘practical man, a civilian and an engineer’53 and had been made on the recommendation of Lord Rayleigh. It was believed that he was better suited than Capper to work closely with the scientists serving on the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and also at the National Physical Laboratory. It was also thought that as a civil servant he would be free of the malign influence which senior military and naval officers, opposed to aviation in any shape or form, could (and did) exert on colonels and captains. Flight Magazine welcomed the appointment:

‘Important changes have, as our readers are aware, taken place in connection with the control of the various departments associated with military aeronautics, the outstanding departure having been the appointment of a civilian, Mr Mervyn O’Gorman – a well-known consulting engineer and automobile expert – to the post of superintendent of the Military Balloon Factory. Hitherto, Colonel Capper succeeded, out of his indomitable energy, in looking after this large and important work in addition to his proper duties as commandant of the Military Balloon School, which in wartime provides the balloon companies that are attached to the fighting forces. How one man could ever be expected to run a factory, design dirigibles, aeroplanes, and other such machines, in addition to instructing soldiers in the art of aerial warfare, is somewhat of a mystery, but Colonel Capper made an attempt that has gone a long way towards laying the foundation of what we hope will in time develop into the finest military equipment in the world. Now that the two departments have been separated, each should progress apace; it is, as we have mentioned, only necessary to look from the roadside to see that developments have already taken place since Mr Mervyn O’Gorman’s accession to the office of superintendent of the factory.’54

There is no doubt that ‘O’G’ was one of the most important figures in the development of aviation in Britain, and set it on a path of sound science and engineering. Not only was he talented himself and filled with an abounding energy, he had the gift for choosing good subordinates and gaining their loyalty. One of the most successful of his recruitments was F.M. Green, who became chief engineer in January 1910.

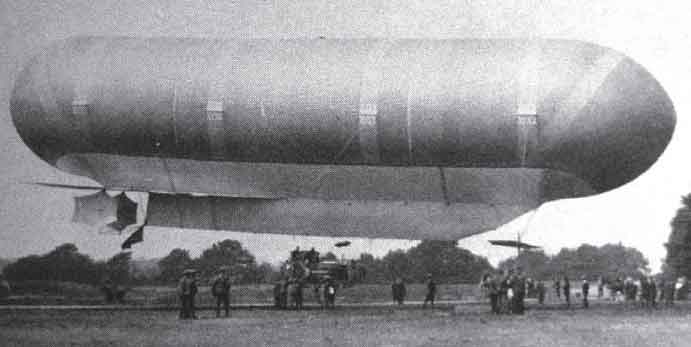

The Royal Navy’s First Airship

Meanwhile, in February 1909, the Committee of Imperial Defence had recommended that £35,000 should be spent on a rigid airship project for the Royal Navy in order to ascertain what its full potential might be; as had been done a few years before in respect of experimental submarines, while the army should concentrate on non-rigid airships for which £10,000 was allocated, and that the development of aeroplanes should be left in the hands of private enterprise.55 This was a triumph for Captain Bacon, who had been under the direct instructions of the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, whose aim had been to secure this funding. It also represented a degree of success for General Nicholson, as some of the impetus for army aviation was kicked into the long grass. Haldane would bide his time. The naval airship order was announced in parliament by Reginald McKenna, the First Lord of the Admiralty, in March 1909:

‘The question of the use of dirigible airships for naval purposes has been under consideration for some time and it has been decided to carry out experiments and construct an aerial vessel.’56

It was noted in the report of the Committee of Imperial Defence that captive balloons and, to a lesser extent, kites, had for many years formed a part of the regular equipment of all modern armies. Great progress with regard to dirigible balloons, particularly in France and Germany in recent years, was remarked upon. With regard to the future use of dirigibles in naval warfare, reliability; ease of mooring; endurance; speed relative to surface vessels; sufficient crew accommodation to allow relief personnel to be carried; a wireless telegraphy set and navigational facilities, were considered as essential. It was added that accurate sights had been obtained by officers at Barrow, using a German bubble artificial horizon device fitted to an aeronautical sextant. The principal use was advocated as scouting and fleet protection at a much lower unit cost than a 3rd Class cruiser or a destroyer. The utility of an airship for dropping explosive devices was considered as unproven. The future use of fixed-wing aeroplanes was also thought to be unproven, particularly with regard to mechanical reliability, carrying capacity, the ability to operate at height and to fly in unfavourable weather. It was also thought that the endurance of aeroplanes would be affected by the physical strain on the ‘driver’. Future combat between airships and aeroplanes was also considered, it being decided that there was no concrete proof at this point as to which would prevail.57

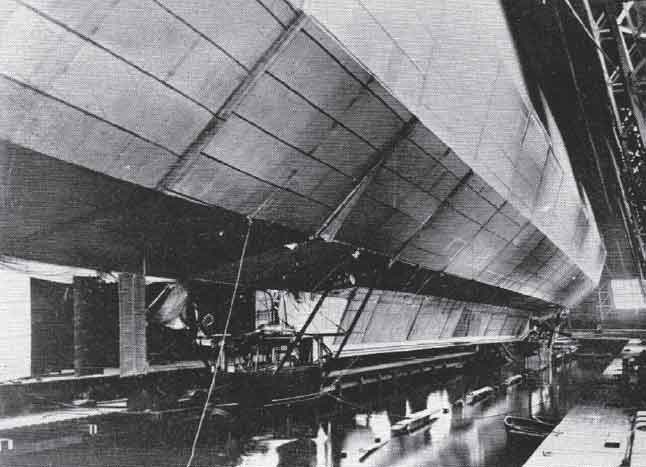

On 7 May a tender from Vickers was accepted.

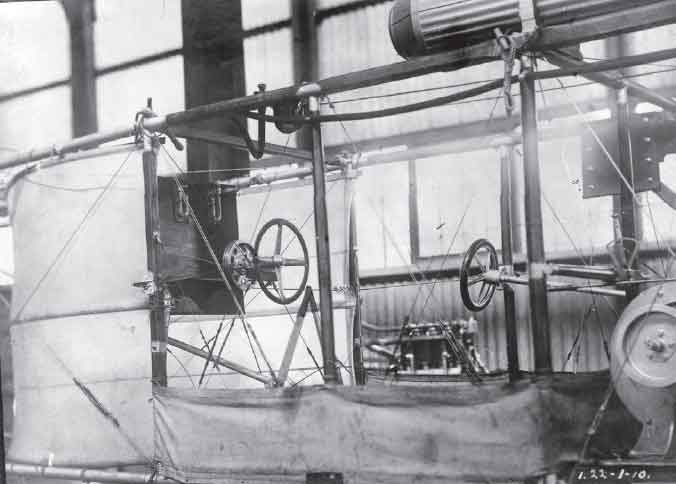

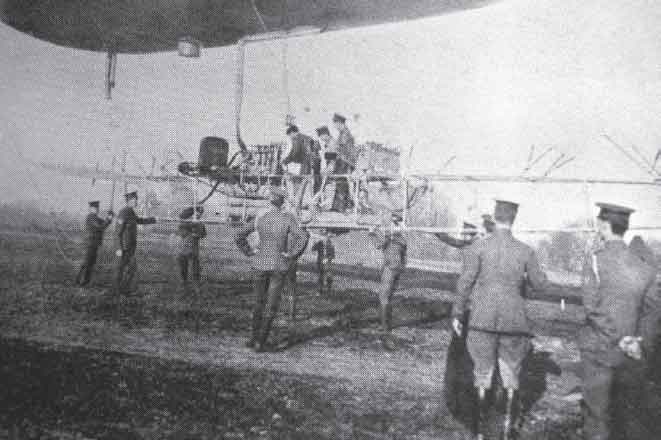

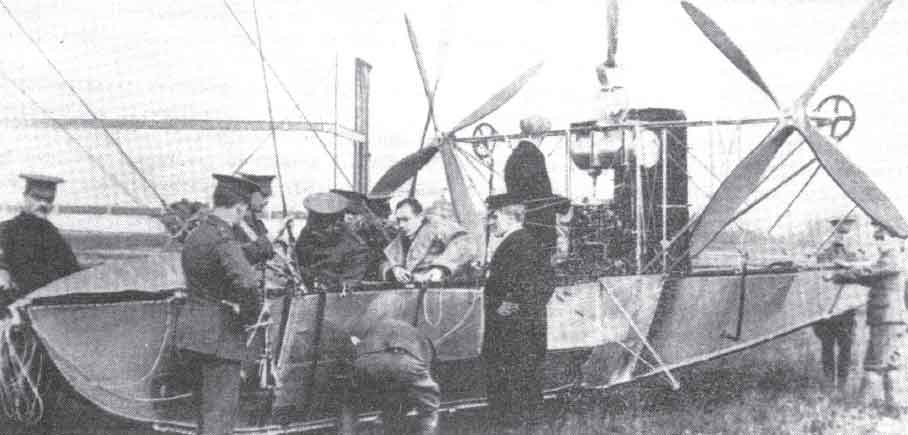

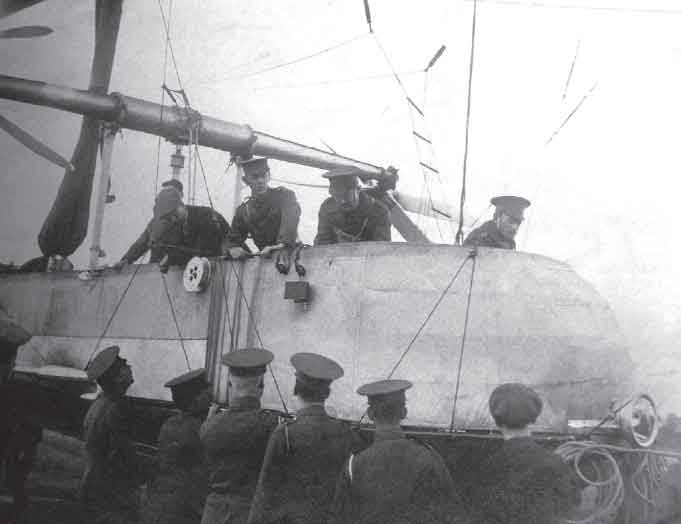

A construction shed was built at Cavendish Dock, Barrow-in-Furness, and it was agreed that the design would be by a consortium of naval officers and Vickers engineers. It must have seemed a very promising career path to Neville Usborne, being taken out of the midst of his generation of officers to take part in a project supported by the First Sea Lord. As well as Murray Sueter, who was in command, and Usborne, the third member of the naval team in the early days was Chief Artificer Engineer A. Sharpe, RN. They were joined later by Commander Oliver Schwann, RN, as Assistant Inspecting Captain of Airships, Lieutenant C.P. Talbot, RN, and Engineer-Lieutenant C.R.J. Randall, RN. The Vickers technical team was controlled by Charles G. Robertson, the Marine Manager at Barrow, who had no prior, ‘experience of aeronautics, nor of the light structural work involved’.58 One of his senior assistants was the mathematician, H.B. Pratt, who calculated the airship in its final configuration was not strong enough to bear the load that would be imposed on it; his advice was ignored. There was little technical knowledge available; therefore construction was very much on trial and error lines. It was a highly ambitious project, with a length of 512 feet (155 metres) and a beam of 48 feet (15 metres); it was as large as any of the Zeppelins constructed so far. Its frame was made of forty transverse twelvesided rings, each connected by twelve longitudinals. Beneath the frame was a triangular keel with an amidships cabin. Inside the framework were seventeen gasbags filled with hydrogen and which had a total gas capacity of 700,000 cubic feet (19,810 cubic metres), each had two valves (of Parseval design) at the top, one automatic, the other manual. They were manufactured by Short Brothers of rubberised fabric imported from Germany. The framework was to be fabricated from an entirely new and untried aluminium alloy, Duralumin, which offered the strength of steel at one third of the weight, and which had been developed in Germany and introduced only very recently. Vickers had considerable difficulty in working it. Originally, the internal bracing wires were also made from Duralumin, but repeated breakages during construction meant they had to be replaced with steel. The silk outer skin, which was waterproofed using an aluminium-based dope, was silver grey on the upper half and yellow below; in order to make the topside as far as possible a non-conductor of heat and so minimise the effect of the sun’s rays on the expansion of the gas, while encouraging the conduction of heat underneath to facilitate the equalisation of temperature between the gas and the surrounding atmosphere. Streamlining was employed with the main body being cylindrical, tapering towards the somewhat blunter nose and tail. Four stabilising fins (two vertical and two horizontal), two sets of quadruplane rudders and two sets of triplane elevators were mounted at the stern. The control surfaces were not hinged, but used Short’s Reversible Patent Aerocurve, which flexed. There was a further elevator under the bows and another rudder to the rear of the aftermost of the two underslung cars, made from mahogany sewn with copper wire and which were connected by a gangway. The original idea was for a long-range scouting and gunnery direction platform to assist the main battle fleet, equipped with wireless telegraphy (WT) which was as much in its infancy as aviation. There was some discussion concerning the possibility of arming the airship with ‘locomotive torpedoes.’59 From an early date, officers of the Royal Navy had been interested in the possibility of using aircraft to deliver torpedoes. This was recorded in Air Publication 1344, History of the Development of Torpedo Aircraft:

‘In the early part of 1911 many discussions concerning the use of torpedo aircraft took place amongst our Naval Officers, Captain Murray Sueter, RN, Lieutenant N.F. Usborne, RN, Lieutenant Hyde-Thomson, and Lieutenant L’Estrange Malone, RN, were amongst those who were particularly interested in this subject. It will be remembered that at that time aircraft were entirely in their infancy; they could hardly carry a passenger, and the idea of carrying a large weight was almost incomprehensible; their use as a weapon was only vaguely discernible. The rigid airship Mayfly was at this time being constructed at Barrow, and the naval officers under Captain Sueter, RN, employed on this work, frequently discussed the prospects of torpedo aircraft. The possibilities were vividly represented by the late Commander N.F. Usborne, RN.’60

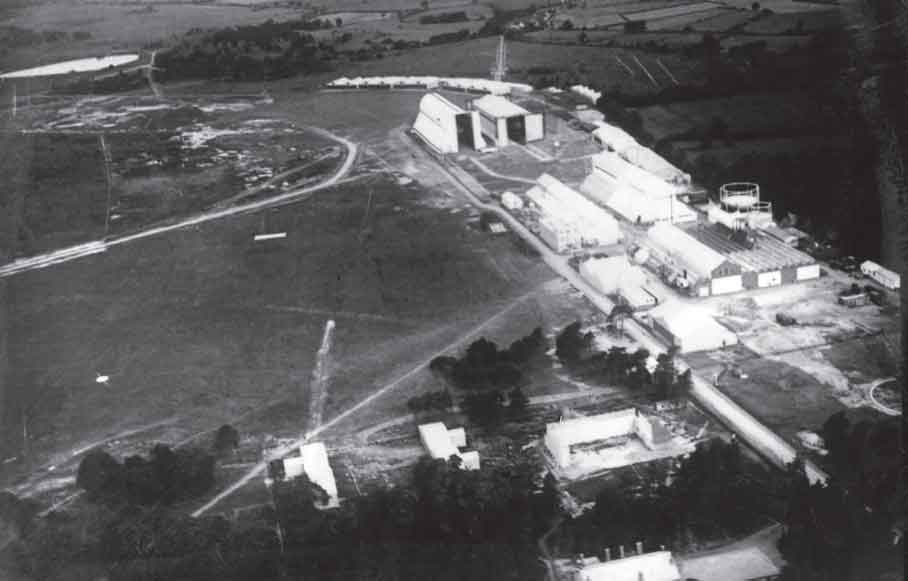

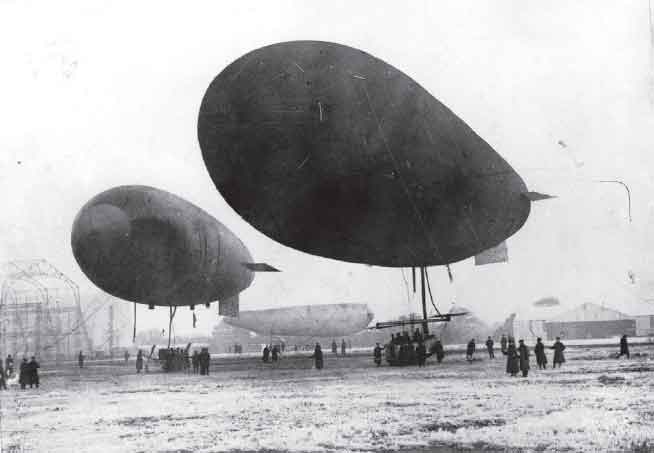

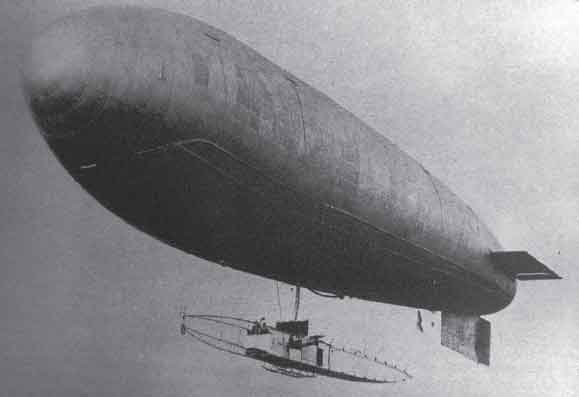

HMA No 1 under construction at Barrow.

Captain Murray Sueter, who was described subsequently as, ‘a brave new warrior of the machine age who had gone, with enthusiasm, from working on submarines and torpedoes, to flying machines and motor vehicles,’61 was appointed Inspecting Captain of Airships, to oversee the design and production of the airship, and so assembled a team of technically minded and promising officers.

The aviation press reported on 30 July 1910:

‘Secrecy at Barrow. EXTRAORDINARY care is being taken at Barrow-in-Furness to ensure that no details with regard to the big naval dirigible under construction there shall leak out. The shed is closely guarded by Marines and only those employed on the work are allowed to enter. It is said that recently a man was found inside the barricade, and, on being taken to the police court, was sentenced to two months imprisonment, although it was not suggested that he was a spy.’62

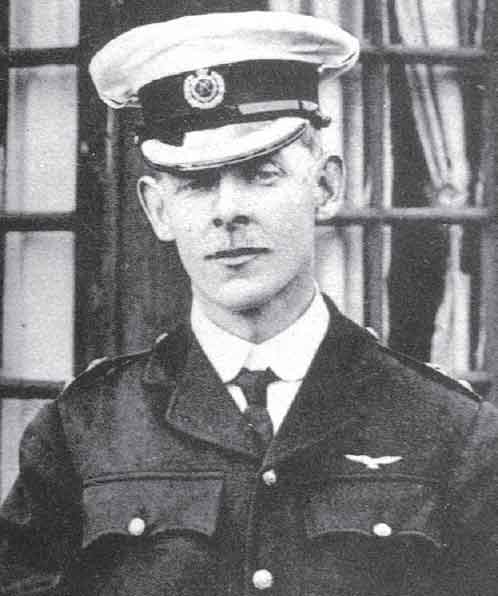

A report has survived covering the period from 26 September 1910 to January 1912, when Lieutenant Usborne served under Sueter. He was appointed to HMS Hermione for Naval Airship No 1. Hermione was a small 2nd Class cruiser which was intended to act as a sea going depot ship for the airship, which was going to be named Hermione, but is better remembered now by the nickname bestowed upon it – Mayfly. HMS Hermione proceeded from Portsmouth to Barrow in September 1910 under conditions of great secrecy – as indeed was all work in the airship shed. Sueter made a significant entry in the ship’s logbook on 25 October:

‘Airship Officer of the Day is to keep herein a careful record of all work carried out in connection with the airship. Lt Usborne is to generally supervise what is entered to ensure that the record is accurate.’63

Sueter’s later report stated:

‘He has conducted himself with sobriety and to my entire satisfaction. A very zealous and capable officer, he has worked hard in making himself an expert in aeronautical work and has considerable knowledge in this line. I have strongly recommended Lieutenant Usborne for promotion. He was selected as captain of Naval Airship No 1.’64

According to a contemporary and more senior officer, Usborne made many useful technical contributions. Indeed, he applied for Aeronautical Patent 6150 ‘Dirigible Airships’ in 1910, which concerned a system to conserve, as a buoyancy aid, the water vapour given off in the process of the combustion of petrol and air.65 Commander E.A.D. Masterman went on to write:

‘He would then have been about twenty-seven years of age, close on his half-stripe as Lieutenant Commander RN. It is no exaggeration to say that of that collection of officers, many of whom were brother torpedo men, his was the outstanding personality. Nothing was decided without his advice and few things undertaken of which he disapproved. His was the knowledge, slight though it now appears, for undertaking the construction of a rigid airship larger then any existing, his the brain and the ingenuity in overcoming unforeseen obstacles and his the drive which he continually brought to bear on Messrs Vickers when the firm demanded time to set matters going and on anyone else connected with the progress of the great experiment. He was the expert and revelled in so being.’66

What was he like? Masterman stated:

‘In appearance he was rather below normal size, a slightly prominent nose, blue eyes, sandy coloured hair and very forcible expression. He hardly ever spoke without emphasis. He had a dominating personality with a vital spark, most difficult to withstand in argument. Not sparing of others, but himself prepared to do as much, or more, than he demanded of them. He was interested in spiritualism, socialism and new thought, music and motor bikes. He was abstemious in his pleasures, very self-disciplined, lived for work, talked, thought and dreamt airships, kept himself very fit. He indulged in ‘height training’, climbing to high parts of the shed or scaffolding and making perilous walks.’67

Lt Cdr N.F. Usborne about 1913 or 1914.

Developments elsewhere while Naval Airship No 1 was under construction

In April 1909 the Parliamentary Aerial Defence Committee was formed to exert pressure upon the government to improve the measures and resources provided for the aerial defence of the nation. An early result of its effectiveness, but not necessarily its sound judgement, was announced in June 1909:

‘AIRSHIPS FOR THE NATION.

‘In connection with the combined efforts of the Morning Post, Daily Mail, and the Parliamentary Aerial Defence Committee to provide the nation with the beginning, at least, of a fleet of airships, we summarise the chief items of the information which has been made public regarding the projects in hand. The new Clément-Bayard airship, on which the Parliamentary Committee has secured a month’s option, is to be about twice the size of its predecessor. According to Mr Arthur Du Cros, MP, the Secretary of the Committee, the length of the envelope will be 300 feet, and the cubic capacity about 227,500 cubic feet. This should provide for the carrying of twenty-five passengers, but during the trip which it is proposed to make from Paris to London, probably only six will be on board, consisting of M Clément, Mr Arthur Du Cros, and the crew of four. This, however, is not definitely settled, except so far as relates to the crew, which will include the pilot, two helmsmen – one for the elevating planes and one for the rudder – and the engineer. Instead of a single engine and propeller, as in Clément-Bayard No I, the new vessel will have two propellers, one on each side of the hull, and each will be driven by a motor of 220 hp. Sufficient petrol can be carried to enable the airship to travel 700 miles, and it is capable of ascending to a height of 6,000 feet. The vessel is still only in sections, but the work of completing her is being pushed on as fast as possible and it is hoped that she will be ready to make the trip to London at the end of August. Since he made his first trip in the original airship last October, it has been a cherished wish of M Clément to be the first man to visit London from abroad by airship. Although he had not contemplated remaining with his vessel in Great Britain for more than a few days, in view of the offer from the proprietors of the Daily Mail to provide a shed for the accommodation of the airship, he has readily acquiesced in the suggestion that he should remain for a month, so as to give as great an opportunity as possible for Members of Parliament and government officials to make themselves thoroughly acquainted with its possibilities. On one day, too, the general public will be enabled to see the airship, for the Aerial League have arranged with Mr Arthur Du Cros to have it on exhibition for that period. With regard to the shed for the airship, towards the cost of which the Daily Mail have so generously supplied £5,000, Mr Herbert Ellis has been entrusted with the work of designing it, and he has visited France in order to make himself acquainted with the sheds already erected there. M. Clément’s own shed is constructed of galvanized iron lined with cork, so as to keep the temperature fairly even both in summer and winter. He suggests that the dimensions of the building should be 300 feet long, 90 feet high and 75 feet wide. With regard to a site for the shed, the War Office have had under consideration the question of providing this, and both Farnborough and Salisbury Plain have been suggested as possible locations, but it is hoped that a suitable piece of land may be obtained nearer London.’68

The Daily Mail in fact raised £6000 for the construction of an airship shed at Wormwood Scrubs, on land provided by the War Office and a private donation of £5000, in what might be described as a fit of misguided, patriotic enthusiasm, had enabled the ordering and purchase of an airship from the French Clément-Bayard Airship Co.

On 19 February 1910, in the House of Commons, the Secretary of State for War, R.B. Haldane, made the customary speech introducing the army estimates for the forthcoming year. He took the opportunity to clarify the government’s policy with regard to aviation:

‘I want now to say a word about dirigibles and aeronautics. The aeronautical department at the National Physical Laboratory got to work almost at once after it was set up last year, and since then it has been found necessary to increase its staff, and the work at Teddington is in full swing. We have also reorganised the construction department at Aldershot, which used to be under the care of Colonel Capper, who did remarkably good work. We want Colonel Capper’s great abilities, however, for the training of officers and men at the Balloon School, and for the work which he has hitherto done we have got hold of a man of great capacity and high eminence, Mr O’Gorman, who is very well known in connection with the construction, not only of motor engines, but other subjects connected with motoring. Mr O’Gorman has now organised a construction department at Aldershot. The next step we propose to take – and we have already decided on its lines – is to substitute for the present corps a regular aeronautical corps, such as exists in Germany, separate from any other corps in the army, devoted to aeronautics. The Balloon School will become the training school for that corps. I am convinced that until we get everything perfectly clear we shall only make very slow progress. The results of the investigations of the committee presided over by Lord Rayleigh are now being used for the designs we are now engaged upon. At present we have one small dirigible at Aldershot, designed by Colonel Capper, (Baby/Beta) which so far has been doing well, and two more are coming from France. There is the Clément-Bayard, the negotiations for which have been undertaken by the Aeronautical Committee of the House, and, if they are satisfactory, it is not impossible that the War Office may purchase it. There is also the Lebaudy, which, through the patriotism of the Morning Post, has been offered to us. It is coming over before long. We are also working on designs of a large dirigible of our own (Gamma) which I hope will be completed, certainly commenced, in the course of the financial year. Then, of course, there is the great naval dirigible, which is rapidly approaching completion at Barrow, and which, I believe, will be launched in the summer. As soon as we have made ourselves masters of the lessons which these teach, we shall go on working at the construction of other dirigibles and shall be in a position of having a fleet. The whole subject is in its infancy. I am never alarmed by reading about the progress of other nations in this respect. Already much of the material possessed by foreign nations is being found to be unsatisfactory, and I have not very much fear that if we put our backs to it we shall find ourselves ahead.’69

It was reported in The Times of 7 April 1910, that Lieutenant Neville Usborne, ‘who had been superintending the construction of the naval dirigible,’ had travelled from Barrow to Paris and would return in the Clément-Bayard airship, taking charge of navigation as soon as the vessel was over British soil. In May it was noted that he was still in France attending the trials.70 Furthermore, Captain Bacon warned him that when crossing the Channel on no account should any mock attacks be made on any of His Majesty’s ships they might fly over.71 Sadly, delays to the programme foiled this plan, no doubt to Usborne’s great disappointment, as he had first been given the Admiralty’s permission to travel to France in connection with the airship project as early as September 1909.72

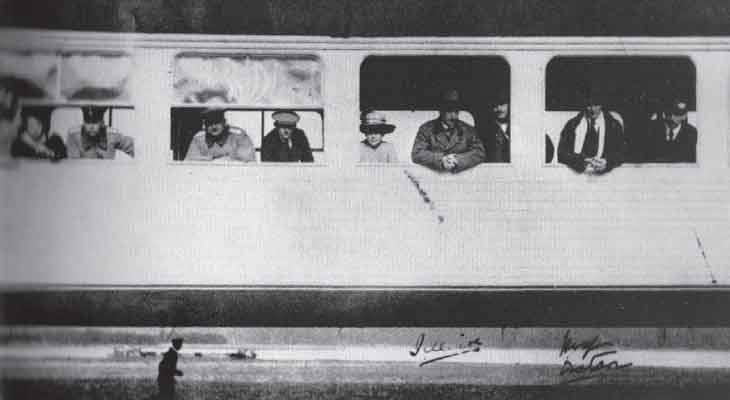

On 16 October 1910, the first airship flight from France to the UK was made by Baudry’s Clément-Bayard II from La Motte-Breuil to Wormwood Scrubs, some 246 miles (398 km) at an average speed of 41mph (64kph). The craft had a length of 251 feet (76 metres), a diameter of 43 feet (13 metres) and a capacity of 247,200 cubic feet (7000 cubic metres), being powered by two 120 hp (90 kW) Clément-Bayard engines. A photograph of the airship’s arrival graced the front cover of Flight Magazine of 22 October 1910 with the caption:

‘PARIS TO LONDON BY AIRSHIP.—The arrival of the Clément-Bayard airship at Wormwood Scrubs on Sunday last. Note the sand ballast being thrown out in order to check too rapid a descent in landing. The military helpers are seen in the distance in readiness to receive the airship immediately it arrives within reach.’

The Clément-Bayard II lands at Wormwood Scrubs.

The airship thereafter was a complete disaster; it had already made more than forty ascents in France, the envelope leaked badly and an argument over payment with the manufacturers ensued. Eventually, half of the originally agreed price of £25,000 was paid. She was dismantled and taken to Farnborough, never to fly again. Had she done so she would have been re-named Zeta.73 The War Office had announced to the House of Commons certain requirements which it desired Clément-Bayard II to meet. These throw light on what was then considered to be the ideal airship for military purposes and are reproduced in Appendix 4.

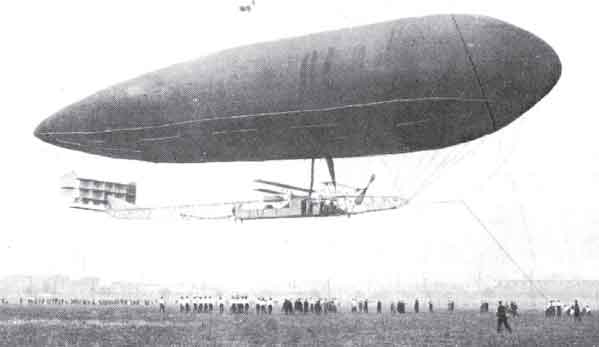

Not to be outdone, a rival newspaper, the august Morning Post, organised in its columns a National Fund which raised £18,000 to acquire a second French airship, from Lebaudy-Frères of Soissons, announcing the success of this venture on 21 July 1909 and described as, ‘a real war-type of dirigible, than which no more up-to-date model exists throughout the world.’74 (Paul and Pierre Lebaudy, together with the engineer Henri Julliot, had been building airships since 1902, including the first dirigible supplied to the French Army in 1906, to which three more had been added by 1909, including République, which was the first to be used by the French Army on manoeuvres.)

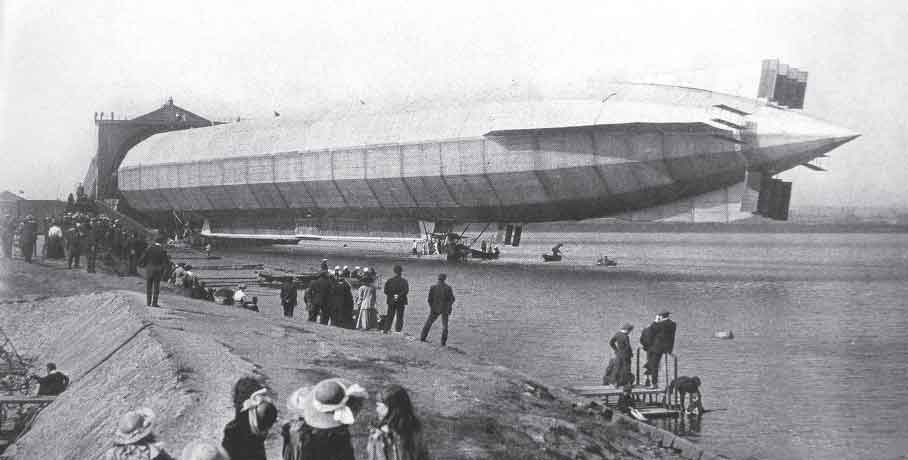

The Morning Post Lebaudy first flew in France in August, at which time Colonel Capper and a Daily Mail journalist, Hamilton Fyfe, were up in her.75 When she arrived on 26 October 1910, she was the largest airship to have been seen in Britain to that date; being 337 feet (102 metres) long, with a diameter of 39 feet (12 metres), a capacity of 353,000 cubic feet (9990 cubic metres) and was powered by twin 135 hp (100 kW) Panard engines, which gave a top speed of 34mph (55kph). In fact helpful winds on its Channel crossing, with a crew of seven, enabled it to average 36mph (58kph). One of those on board was Major Sir Alexander Bannerman, RE, ‘a stout, moustached, dyed-in-the-wool officer’76 who had succeeded Capper at the Balloon School a fortnight earlier, despite knowing little about airships or aeroplanes, but possessing, ‘a certain amount of practical experience in ordinary gasbag ballooning,’77 and an absolute belief that attack from the air would be a hit and miss affair, with the likelihood that not one bomb in 10,000, from a height of 5000 feet (1524 metres), would hit a battleship.78 In the opinion of one aviation historian:

‘The War Office attitude was demonstrated still further in its treatment of the purely military Balloon School. Colonel Capper retained his post until he became due to promotion from brevet to substantive rank on 7 October 1910. The War Office refused to let him continue as commandant at this higher rank, but instead downgraded the post to that of major, and appointed Major Sir Alexander Bannerman as his successor.’79

The Lebaudy airship arrives at Farnborough on 26 October 1910. (Via Ces Mowthorpe)

Colonel John Capper (1861–1955) became the Commandant of the Royal School of Military Engineering at Chatham, so removing an air expert with a worldwide reputation from direct involvement in military aviation. He served throughout the First World War as a Corps Chief Engineer, Divisional Commander and Director General Tank Corps, attaining the rank of major general and a knighthood.

The Lebaudy was no more successful than the Clément-Bayard II. Unbeknown to the authorities at Farnborough, the designers had increased the height of the airship, with the result that as it was being walked into its specially built shed, the envelope caught on the roof and suffered a serious tear. (This is described in full in Appendix 5.) Repairs (and alterations to the shed) took several months. When it flew again in May of the following year, with a French test crew in control and Major Bannerman in attendance, all went well at first, with Cody and Geoffrey de Havilland circling around the airship in their aeroplanes. But after about an hour in the air it proved to be unmanageable, and it descended and crashed out of control, tearing down telegraph poles and uprooting railings in its path, and in front of a large crowd which had come to watch the spectacle, luckily without killing or badly injuring anyone.80 After another Franco-British argument the airship was scrapped. So ended: ‘A sad and ridiculous chapter in British aeronautical history.’81 R.B. Haldane may well have been tempted to say, ‘I told you so’ as the two debacles certainly vindicated his view of a measured scientific approach as opposed to buying something foreign off the shelf just because it was there.

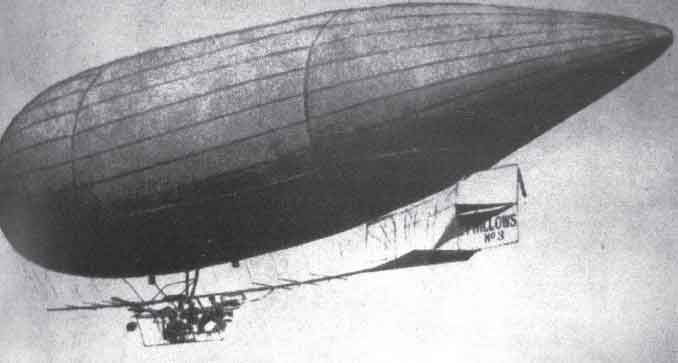

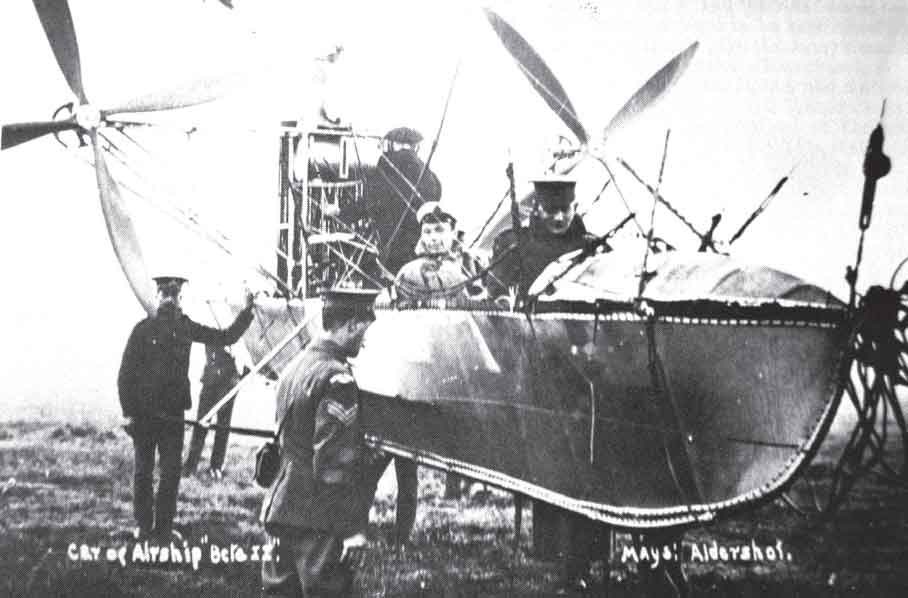

A purely civilian enterprise had much greater success, as on 4 November 1910, E.T. Willows and Frank Gooden made the first crossing of the English Channel by a British aircraft in the Willows No 3 City of Cardiff, which was 120 feet (36 metres) long, 23 feet (7 metres) in diameter and with a capacity of 32,000 cubic feet (905 cubic metres). Departing from Wormwood Scrubs they crossed to Douai, where they force-landed. The airship was deflated and repaired at the Clément-Bayard works and then flew to Paris on 7 January 1911, where it undertook a number of passenger-carrying flights:

‘The Willows Trip to France.

‘In view of the way in which foreign aviators are treated when they happen to land on British soil, it is instructive to note the treatment meted out by our neighbours across the Channel when a Britisher happens to land there. On Mr Willows coming down at Corbehem, near Douai, in order to discover his whereabouts, he was rather surprised when three gendarmes mounted guard over his ship, and an officer demanded the payment of about £30 Customs duty. Matters were eventually smoothed out by the Aero Club of France, who explained that the incident arose simply owing to the fact that notice had not been given to the Customs authorities, who were bound to act as they did. The airship was brought out from the Daily Mail garage at Wormwood Scrubs on Friday afternoon, and, with Mr E.T. Willows piloting her, assisted by Mr W. Gooden in charge of the engines, a start was made at 3.25 pm. Steering straight across London, the aeronaut then made for Bexhill, and at 6.35 the English coast was left behind. Two hours later the French coast was in sight. At 10 o’clock the vessel was taken to a height of 5,500 feet, in order to enable Mr Willows to steer by the stars, as the clouds prevented him picking out the places passed over. Later, the weather became very foggy, and at 2 o’clock in the morning Mr Willows decided to bring his craft down. Mr Willows had no idea where he was, but when the two aeronauts had got the machine on the ground safely anchored they found a peasant and sent him off to the village to get help. The framework of the car was somewhat damaged in the landing. M Breguet, whose flying ground at La Brayelle is not far off, motored over to render what aid he could to Mr Willows, and afterwards, when making a second visit, he flew over in his aeroplane. Mr Willows had intended, after repairing his machine, to complete the journey to Issy, and a large crowd gathered there on Sunday afternoon to welcome him. The weather conditions, however, changed in the meantime, so that Mr Willows deemed it advisable not to go on. He therefore had his balloon deflated, packed up and sent to Issy by rail, where it found a temporary home in M Clément’s dirigible shed.’82

Willows No 3. (Via Patrick Abbott)

Willows himself was hopeful that the government would support his efforts by ordering an airship from him. The venture had at least raised his public profile and increased his expertise in airship handling. He was reported in the press as commenting, ‘Of course, I have obtained experience which would be of great value in training men in the handling of small dirigibles and by this means the best results are obtained afterwards in the handling of the larger class. This, I think, is the lesson to be learned from the numerous disasters to the Zeppelins.’83

Meanwhile, the army’s airship men had been making some progress. The unsuccessful Baby had been transformed into the Dirigible IIa, soon renamed Beta, which had been completed in February 1910. It is worth noting that in this month a survey noted that there were twenty-six airworthy airships in the world, fourteen in Germany, five in France, two in Italy, and one each in Great Britain, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Russia and the USA.84 Beta’s envelope was that of the Baby increased in length by 20 feet (6 metres) and it now had a volume of 35,000 cubic feet (990 cubic metres). The car was composed of a long frame, having a centre compartment for the crew and engine. The 35 hp (26 kW) Green engine was retained in an improved form, driving two wooden two-bladed propellers by chains. Beta was fitted with an unbalanced rudder, while the elevators were in the front of the frame. A contemporary account described it as being many times larger than its predecessor, having the appearance of a fish and being coloured dead chrome-yellow from end to end. The reporter judged that it appeared to be thoroughly under control from the moment of its ascent, throughout an hour-long flight in the vicinity of Farnborough until it returned to its shed, which no doubt would have gratified the aeronaut in charge, Colonel Capper, assisted by Captain King, Mr Green and Mr McQuade, the Works Manager.85 Further test flights were made in March by Captain Carden and Lieutenant Waterlow, which encouraged thoughts of a longer voyage.86 In this they were successful. On 3–4 June 1910, they flew to London and back during the hours of darkness, with a crew consisting of Colonel Capper, Lieutenant Waterlow and Mr T.J. Ridge of the Balloon Factory, taking about three and a half hours for the round trip; the first night flight:

‘The ascent was made at 11.40 pm and the course was set by the stars. When the main London and South-Western railway line was reached, the airship followed the metals until the Brooklands motor track at Weybridge was reached. Then a straight line to St Paul’s was taken, the Thames being crossed three times in its windings. The first crossing at Thames Ditton, the second near Hurlingham and the third near Battersea Park. The dome of St Paul’s was circled and the return journey, with a following wind, was made at top speed, between 25 and 30 miles an hour. The main London to Portsmouth road was struck at Hounslow and proved a splendid guide to the aeronauts, who followed it through Staines and Sunninghill to Farnborough.’87

Beta – the pilot’s seat and controls. (Via Nigel Caley)

The flight was followed on the ground by the Balloon Factory’s Chief Draughtsman and Chief Mechanical Engineer in a motor car – but so rapid was the progress made by Beta that they lost sight of the airship not long after it departed from Farnborough Common. Harry Harper was offered a flight in Beta one afternoon:

‘Clad in a suit of overalls which had been lent me, I was given the task of keeping the log of the trip, being provided with an official logbook for the purpose, and a stub of pencil.

‘The engineer crouched in a tiny seat just behind his noisy motor. We other two, the skipper and myself, were poised perilously on a little railed platform, which had two or three boards stretched across a metal frame to form its floor. There was no support of any kind to grip at save a couple of flimsy handrails which, as soon as the engine began running fast, vibrated so much that one could scarcely hold them. The platform too shook violently, and the whole affair was distinctly intimidating.’88

Beta I in 1910. (Museum of Army Flying)

As Harper tried to keep his mind on the task of entering engine data, height and course, his hands, face and the pages of the logbook became covered in a thin film of oil blown back from the engine. Worse was to follow:

‘We began to encounter a gusty, bumpy wind. The little airship began to make bad weather of it, like a small yacht in a rough sea. Up she went at the bow and then down again with a sickening lurch. Then she would roll and give a sort of uneasy wobble. All the time I was clinging for dear life to that bleak exposed platform, trying to prevent myself looking down apprehensively through the cracks in the floorboards.’89

He noted that he was very glad to return to earth, that he had managed to complete all the log entries required and that Beta made a good landing despite the bumpy conditions.

Gamma – the control position. (Via Nigel Caley)

Beta was followed by Gamma, which first took to the air for a 50 minute flight on 2 February 1910 in the capable hands of Capper and Waterlow. Her rubber-proofed fabric envelope had a capacity of 75,000 cubic feet (2122 cubic metres), with an 80 hp (59 kW) Green engine in the extended car driving swivelling propellers, the gears and shafts of which were made by Rolls-Royce. The engine drove the propeller shafts direct, one from each end of the crankshaft, allowing a top speed of 30mph (48kph). The engine gave some teething problems to begin with, but in March, Captain Carden and Lieutenant Waterlow carried out a series of successful test flights.90 Gamma was badly damaged in a spring gale while moored out at Farnborough, but she was fully repaired, so leading to the following report in June 1910:

‘Gamma Out Again. Having had the damage sustained during the recent gale repaired, the army airship Gamma was out for a trial run on Saturday afternoon. Piloted by Lieutenant Broke-Smith, RE, with Lieutenants Cammell and Reynolds, and Mr Green, as crew, the dirigible manoeuvred successfully over Farnborough Common for forty minutes. The only incident was the stampeding of some horses belonging to the Oxford University Territorials, which were apparently frightened by the whirr of the motor as it passed over them.’91

Gamma or The Yellow Peril in 1910. (Museum of Army Flying)

Not long afterwards, the airships received a visit from King George V and Queen Mary, which was described as follows:

‘Army Airships Inspected by the King and Queen. On Monday afternoon, during the time HM the King was at Aldershot, the two army airships, Beta and Gamma were taken out and cruised over from Farnborough. The former then returned to her shed, where she was closely examined by His Majesty, who rode over from the camp. The Queen, who had motored over to Farnborough to see the dirigibles, also had the mechanism of Beta explained. Gamma had some little engine trouble, and descended at Crookham, but later returned to the balloon factory. On Wednesday afternoon both airships were out, Gamma cruising over the vicinity of Guildford, while Beta started off from Farnborough in the direction of Bournemouth.’92

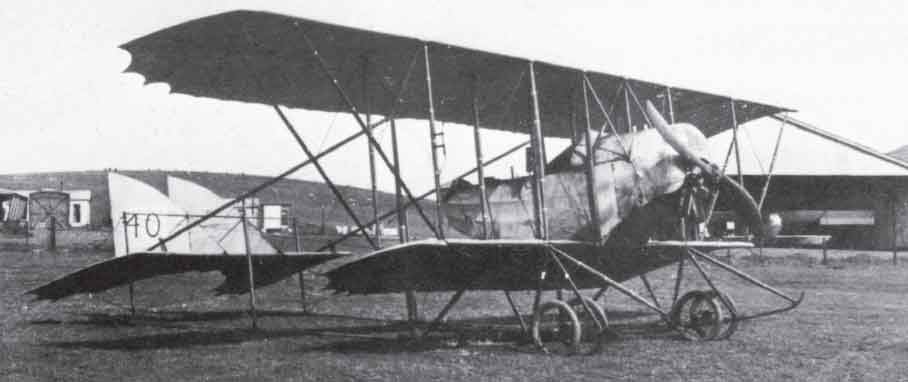

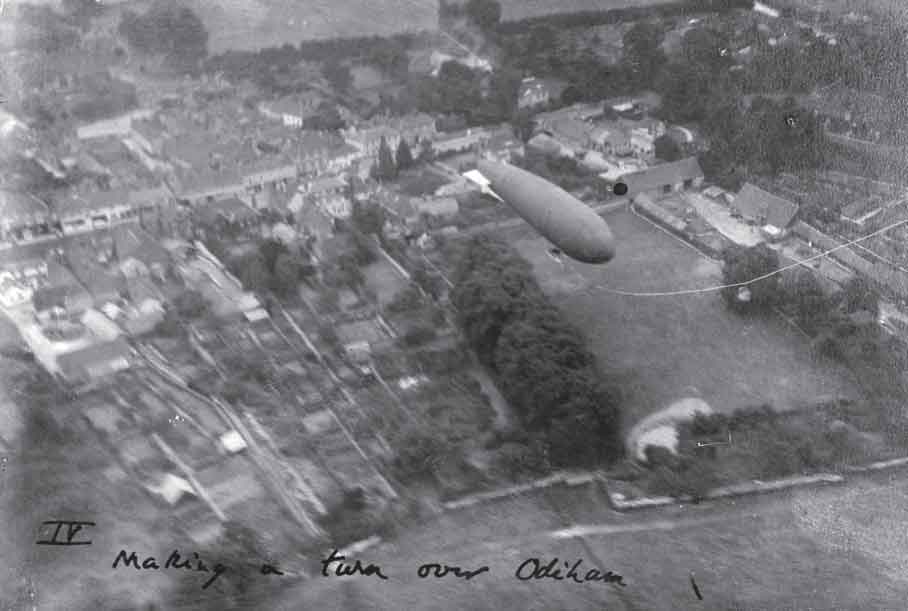

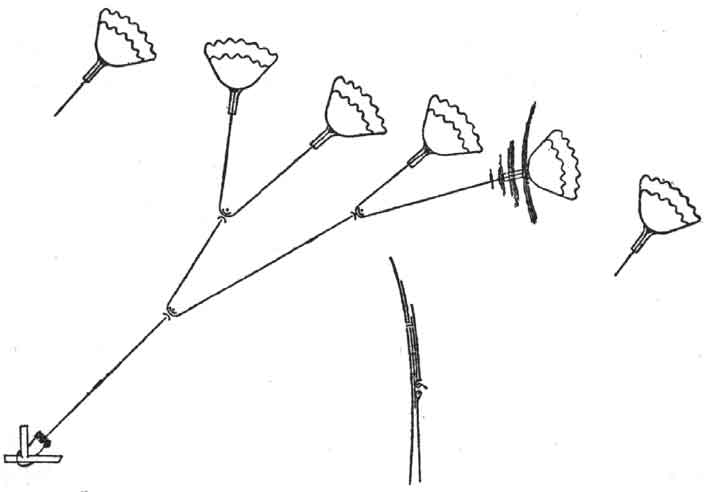

Beta made another visit to London in July, this time in daylight, crewed by Lieutenant Broke-Smith, Lieutenant T.J. Ridge of the London Balloon Company, RE (Territorials), and Sergeant Ramsey, RE. (This was the first Territorial Force air unit and was in existence for five years from 1908 until 1913. Ridge was also the assistant superintendent of the Balloon Factory.) This time navigation was by map and compass, and slow progress was made against a stiff headwind. An average height of 1500 feet (457 metres) was maintained and the conditions were smooth, apart from cross currents encountered over the Thames valley. Once over the city, large crowds stared upwards at the graceful sight as Beta passed over the City of London, the Strand and the Houses of Parliament. The return trip was accomplished at a speed of 35mph (56kph) and, as there was petrol to spare, a detour was made to fly a circuit over the Royal Pavilion at Aldershot, being watched from the windows by King George and Queen Mary. On landing back at Farnborough, the airship’s crew were greeted by cheers from the crowd assembled on the common.93 Later, Beta had a minor mishap, making a forced landing near Andover due to a broken crankshaft. The inherent safety of the airship was demonstrated, as a safe descent was made into a field near a farmyard. Farnborough was speedily advised of the difficulty, and spare parts and mechanics were dispatched by motor car. Soldiers were summoned from nearby Tidworth and Beta was transported to a local foundry, where repairs were effected during the night, so allowing Beta to proceed to Bournemouth the next day.94 Not long afterwards permission was given, with some reluctance, in case that it would frighten the troop horses, for both aeroplanes95 and airships to take part in the army manoeuvres of September 1910, to be held on Salisbury Plain. Instructions were issued: