From August 1914 to February 1916

The First War Patrols

On 4 August 1914 Usborne reported to the Admiralty that he had, under his command, four RNAS flying officers, a meteorological officer, seventy-seven ratings, an airship handling party of two petty officers and forty-eight boys, a military guard of sixty-two NCOs and men, commanded by two RE officers, and one further RE officer and twenty-nine men, whose concern was the completion of a blockhouse.1 Building work was continuing and accommodation was chiefly under canvas. After the declaration of war, the Kingsnorth airships carried out very valuable, long duration patrols over the Straits of Dover, escorting the troopships taking the British Expeditionary Force to France between 9 and 22 August. No 3 had a greater range than No 4 and could fly further to the north-east over the Channel approaches. Indeed, the initial British aerial missions of the war were carried out by these two airships. On the very first night of the war, No 4 came under the fire of territorial detachments at the mouth of the Thames on her return to her station. The enthusiastic, but trigger-happy soldiers, presumably imagined that she was a German airship on a spying mission over the naval dockyard at Chatham.

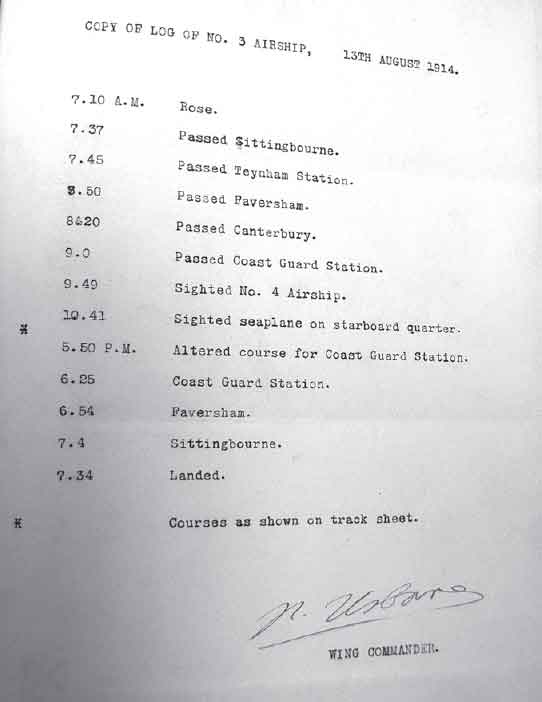

Log of No. 3 Airship, 13 August 1914.

7.10 a.m. Rose.

7.37 Passed Sittingbourne.

7.45 Passed Teynham Station.

7.50 Passed Faversham.

8.20 Passed Canterbury.

9.00 Passed Coastguard Station.

9.49 Sighted No. 4 Airship.

10.41 Sighted seaplane on starboard quarter.

5.50 p.m. Altered course for Coastguard Station.

6.25 Coastguard Station.

6.54 Faversham.

7.40 Sittingbourne.

7.34 Landed.

A chart of a patrol by Airship No 3 on 14 August 1914.

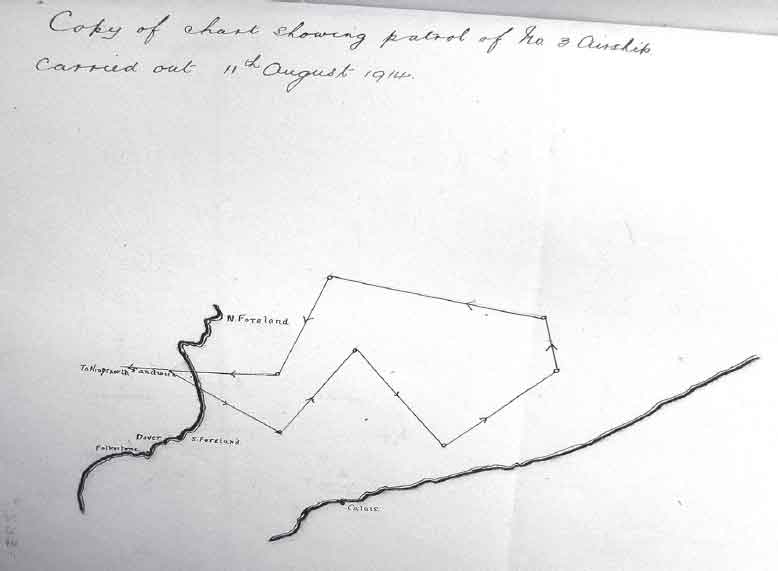

Chart of patrol of Airship No 3 on 11 August 1914.

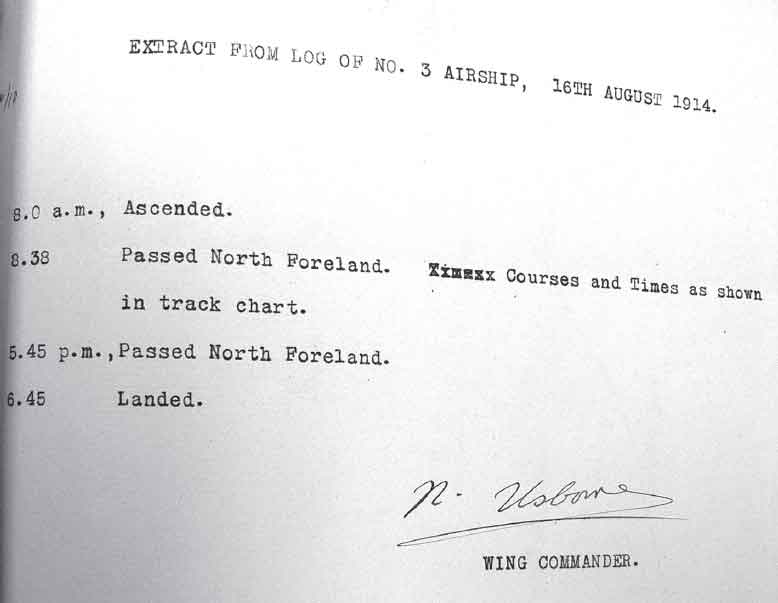

Neville’s account of a patrol on 16 August 1914.

Log of No. 4 Airship, 13 August 1914.

7.40 a.m. Left Kingsnorth.

9.28 Passed Coastguard Station, shaped course for Calais.

10.35 Shaped course for Dover.

11.25 Shaped course for Calais.

11.35 Broke one blade of port propeller, rendering it necessary to change two for new blades. Off Dover one blade of the port propeller burst and flew off, narrowly missing damaging the rigging near the envelope. We were able to fit two new blades while under way and continue the patrol. This took one hour and twenty minutes.

12.55 pm Proceeded to Calais.

1.40 Shaped course for Dover.

2.12 Course as requisite to arrive at Calais.

2.52 Dover.

3.20 Calais.

4.00 Dover.

4.45 Calais.

5.45 Deal.

7.30 Arrived at Kingsnorth.

7.53 Landed.

It will be seen that the Parseval, which could not fly for a whole day without landing for the replenishment of fuel, plied continually between Dover and Calais, while the Astra-Torres, which was the stronger ship, laid her course far to the east and north-east to search the Channel for the approach of hostile craft. Once the expeditionary force was safely across the Channel, these routine patrols were discontinued, though both airships and seaplanes continued to make special scouting flights over the North Sea and Channel.2

Murray Sueter related a story which he believed spoke volumes for the average naval officer’s appreciation of the RN’s aerial assets at that early stage of the war:

‘During one of the patrols an amusing incident occurred, which I relate to show how little the navy bothered to study airships before the war. One of our coast patrol cruisers, with the admiral on board, suddenly sighted one of our airships. They at once cleared lower deck, and placed below all surplus ammunition not required to fire at the airship, which they thought was a Zeppelin. A few days after this incident, the Chief of Staff sent for me, and wanted to know what I meant by letting one of my airships go near this patrol cruiser, as the admiral thought it was a German Zeppelin. I said, “He couldn’t possibly have thought that, sir, as it was the tri-lobe Astra-Torres, commanded by Wing Commander Usborne (one of our ablest naval torpedo officers and expert airman) and not in the least like a Zeppelin, and the admiral, who had been Director of Operations at the Admiralty for two years, ought really to know the difference.”

‘“Do not be absurd, DAD [Director of Air Department],” was the answer, “how could you expect the Director of Operations to find time to go and look at one of your airships? What nonsense, indeed!” Of course, the naval airmen were always wrong. After this I had a book of silhouettes of every aircraft – our own, allied, and enemy – specially prepared and circulated for guidance of those who had been too busy to spare a second to look at our airships.’3

Account of a patrol of eleven and a half hours.

Log of No 3 Airship for 13 August 1914.

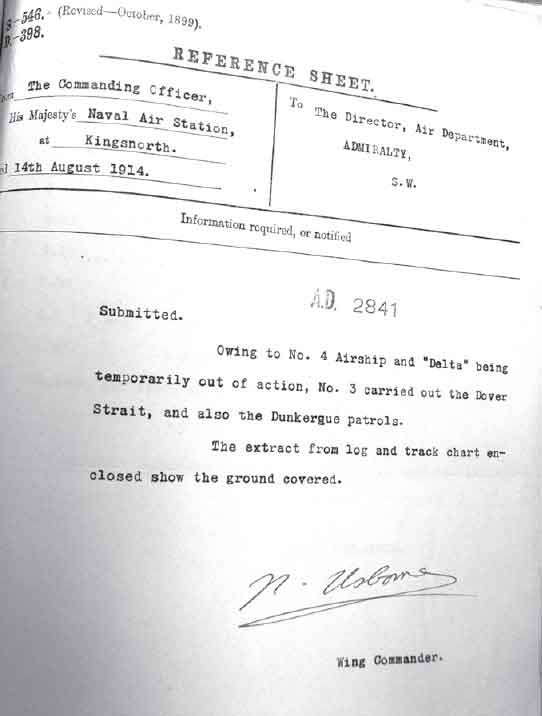

Report for 14 August.

Extract from Log of Airship No 3 on 11 August 1914.

Further remedial measures included supplying naval control centres with the start and finish times of patrols, the issue of ‘dozens of photographs and line drawings showing the difference between our ships and German Zeppelins’ and large White Ensigns with jacks being supplied to the airships, ‘it is not seen that much more can be done at present’.4

On the other hand, Sueter himself was not the easiest of subordinates, being enthusiastic, unorthodox and somewhat impatient of minds unable, or unwilling, to grasp matters which he perceived to be of fundamental importance. In return, salt-horse senior officers regarded the RNAS in general, and Sueter in particular, as insolent upstarts who needed the beneficial lash of old style naval discipline at regular intervals.

On 23 August 1914, a letter was sent to Usborne from Commander Edward Masterman, now at the Air Department in the Admiralty. It noted that he was:

‘Disappointed by the failure to get No 4 (Parseval) back to Farnborough at the required time. The sooner she gets back the better, as her propellers are practically ready for her. She will have to do without reversing gear for a bit as that is not yet designed, but I don’t think it highly essential. I do not think, nor do others, that she ought to continue flying with metal propellers after the accident in the air the other day.’5

On an early war patrol, No 4 had shed a propeller blade, but as she carried a spare, this was changed in mid-air. However, the airship drifted towards the Belgian coast where the flashes of gunfire illuminated the gathering dusk. Masterman went on to remind Usborne that Maitland was in charge at Farnborough and anything wanted from him should be by request and not framed as an order. (As will have been noted, Wing Commander E.M. Maitland had a considerable background in lighter-than-air aviation – he took up ballooning in 1908 and, on 18 November 1908, together with Major Charles C. Turner and Professor Auguste Gaudron, he flew in the Mammoth from Crystal Palace to Mateki Derevni in Russia, a distance of 1,117 miles (1,787 kilometres) in 36½ hours – a new British long-distance balloon record. In 1909 and 1910 he was attached to the Balloon School and whilst there he also undertook experiments with powered aircraft, but, following a bad crash, decided to concentrate on airships. On one occasion, he took a couple of young ladies aloft in a balloon, only to come down on the rooftops of Kensington, necessitating rescue by the fire brigade. He had been serving in positions of authority since 1911.) Usborne was urged to be ‘more tactful’. Masterman went on to make some recommendations as to future commands:

‘Fletcher, No 6 (Parseval Vickers) with No 5’s (Parseval Vickers) crew, Woodcock, No 7 (Parseval Vickers) with Cook as coxswain, No 4, Hicks or Cunningham. Can you straighten this out now as you think?’6

And concluded by warning:

‘Look out you don’t get an incendiary bomb dropped on the wooden shed by an aeroplane from Ostend.’7

In the event, HMAs 5, 6 and 7 suffered delays and were not completed until later in the war. On 28 August, HMA No 3 (Astra-Torres), which carried – as offensive weapons – a Hotchkiss machine gun and four Hales grenades, left Kingsnorth at 06.30 under the command of Neville Usborne and landed at Ostend at 09.45, joining a detachment of RNAS aircraft and armoured cars. Other officers on board included Flight Lieutenants W.C. Hicks, Flight Lieutenant E.H. Sparling and Flight Sub-Lieutenant Hartford. Moored out under the ingenious principle of what Usborne termed virtual mooring, involving only the use of wires and screw pickets, it was used for scouting along the Belgian coast to the Schouwen Bank lightship. It returned to Ostend each evening before nightfall. After Ostend was occupied by the Germans, it moved to Dunkirk, where a photograph showed No 3 moored to a portable mast alongside Commander Samson’s Dunkirk Squadron. It carried out a daring reconnaissance flight over the town in broad daylight – no hostile action taken, as the enemy must have been too astonished to react. Usborne and No 3 returned to England after a week. He reported to the Admiralty that the, ‘following services could be rendered:’

1. By day, scouting for the fleet, which was short-handed in the matter of small craft.

2. By night, standing over the fleet and assisting the destroyers in detecting any attacks.

3. By night, watching the movements of any large body of troops in the vicinity, whose positions might have been ascertained by day.

4. For spotting the fall of shot fired by light cruisers and mortar boats against hostile troops advancing to the attack on land.8

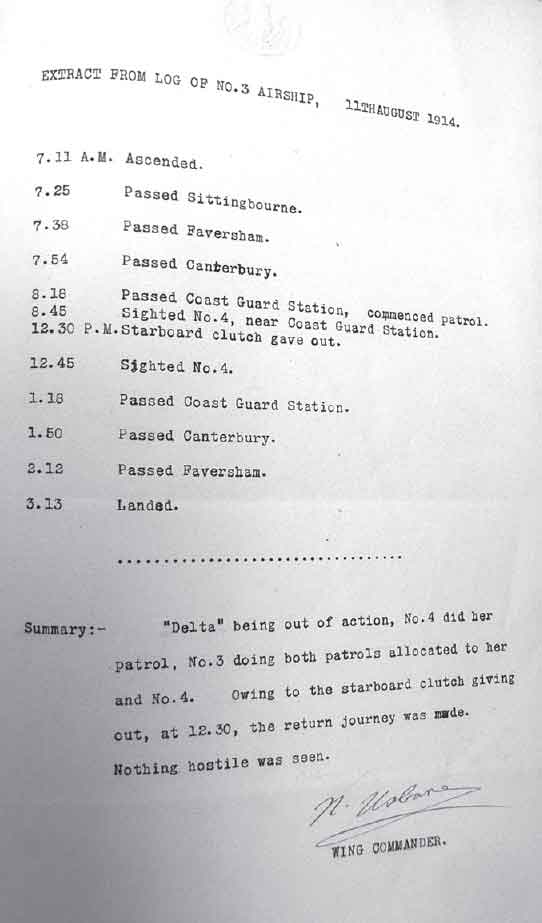

HMA No 3, Short Biplane No 42 and BE2a No 50, near Dunkirk in September 1914. (J.M. Bruce; G.S. Leslie Collection)

Night flights over London were made from Kingsnorth to evaluate possible Zeppelin attacks, and give the searchlight crews and night fighting aircraft some practice. One of these was the future Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, who, as a newly qualified lieutenant, flew anti-Zeppelin patrols from Northolt:

‘I was told to see if I could find an airship which was going to fly around pretending it was a Zeppelin. Well, by the most astonishing bit of good fortune, both for the airship and myself, I found it by nearly running into it. It had put its lights on when it saw me coming and I suppose that was regarded as a bit of skilful scouting navigation on my part, whereas, as a matter of fact, all I had done was to fly blindly into the night and hope for the best.’9

Beta was detached from Farnborough, firstly to Roehampton and then to Wormwood Scrubs, making a number of flights over London, apparently in defence of the capital:

‘On Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, the airship Beta carried out a number of evolutions over the Metropolis. After circling above St. Paul’s, Buckingham Palace, and other prominent places, the airship came down very low when in the neighbourhood of Trafalgar Square, and then rose to a great height before disappearing in the haze. The King and Queen watched the movements of the airship with great interest from Buckingham Palace.’10

On 22 September, on a calm but foggy night, Beta ascended from Wormwood Scrubs, but lost her bearings and was unable to return to base. Cruising at 500 feet (152 metres) Beta’s crew found it impossible to determine whether she was over the metropolis or open countryside. A navigational fix was eventually made by spotting the sign at Golders Green Underground station in North London, which was picked out in electric light. A circuitous and careful return to base was made at a height of 300 feet (91 metres) or lower, landing safely after a stressful two and a half hours in the air.11 Sueter wrote that these evolutions had a useful practical purpose:

‘Orders were promulgated for controlling the lighting of London, and I sent Wing Commander Maitland across London in the airship Beta, commanded by a very able airman, Flight Lieutenant K.J. Locke, to inspect and report on the restricted lighting arrangements, also Commander Groves was sent over in a free balloon for the same purpose. Other balloons were sent over from time to time, and I also sent Wing Commander Neville Usborne, the gallant Commander of No 3 Airship, to inspect the lighting of the Strand, Regent Street, Oxford Street, and Trafalgar Square from the air.’12

Good practice was also obtained by the crews of guns and searchlights in picking up and training on the airship. Beta inspected the lighting at Woolwich Arsenal a few days later.13

In the summer of 1914, two further Astra-Torres had been ordered by the Admiralty, HMA No 8 (very similar to HMA No 3) and the smaller HMA No 10. Usborne was directed to travel to France in October 1914. His passport, signed by the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, noted his age as thirty-one and his rank as commander RN. The purpose of travel was given as, ‘to assist with delivery of an Astra-type airship.’14 A further letter of endorsement, dated 13 October 1914, was written by Wing Commander Oliver Schwann, RN, from the Admiralty Air Department:

‘Wing Commander Usborne is proceeding to Paris to assist in taking delivery of an Astra-type airship built for the Admiralty. If circumstances permit and the French Government allow of this, he should visit Epinel to examine the airship facilities at that place. It is requested that he may be rendered any assistance possible in carrying out his duties.’15

On 2 November 1914, No 3 took part in successful trials with the steamship SS Princess Victoria, when the airship dropped a tow rope onto the quarter deck of the ship from a height of 300 feet (91 metres). The rope was made fast and the airship was towed into and against a 15mph (24kph) wind, whilst the steamer worked up to her full speed of 21 knots (39kph). The crew of the Princess Victoria experienced no difficulty and the airship’s helmsman was able to maintain complete control at all times. The purpose of the experiment was to ascertain if it would be a practical proposition to tow airships in this way, thereby increasing their range and utility as fleet scouts, and improve the radius of action in the anti-submarine role. It was also judged to be reasonable to assume that the airship could have been hauled down close enough to the ship to permit the changeover of crew or refuelling. An observation car capable of being lowered from an airship was also designed, built and tested. A proposal to tow HMAs No 3 and No 8 across the North Sea on a cloudy night, lower the observation cars and then drop bombs on a chosen target from low-level, progressed no further than as a demonstration of Usborne’s fertile imagination and desire to get to grips with the enemy.16 Another trial at this time involved the use of a motorised mooring trolley running on rails laid along the length of the airship shed, using the old airship Delta.17 On 17 December, No 3 was deflated for overhaul and on 22 December, under Usborne’s command, Astra-Torres HMA No 8 was flown at Kingsnorth. Some defects were found so it had to be deflated again for alterations.

An event of considerable interest took place at Kingsnorth on 17 December. C.G. Spencer & Sons Ltd, ‘Makers of Balloons, Airships, Parachutes, Gas containers and Aeronautical Apparatus of Every Description,’ in the form of Mr Spencer himself, demonstrated a parachute which the firm had designed and manufactured. Spencer jumped from HMA No 3 from a height of 1000 feet (305 metres), the parachute opening within 100 feet (30.5 metres) and landed almost precisely on the intended spot below. The C.G. Spencer Static-Line (Automatic) Parachute was adopted for use by the crews of stationary observation kite balloons, but not at this stage for airship personnel, or – until after the war – for pilots, observers and gunners of fixed-wing aircraft. Shamefully, the Air Board did not approve of parachutes for pilots, in case it encouraged them to abandon damaged aircraft rather than trying to recover them to base for repair. While this experiment was taking place, Clive Waterlow was engaged on a series of trials at Kingsnorth testing the suitability of the smaller airships for carrying weapons such as a Lewis gun mounted on top of the envelope, or the heavier calibre Davis recoilless rifle.

As the year drew to a close, Stanley Spooner, the editor of Flight Magazine, in his final editorial of the year, gave his views on lighter-than-air craft in general and Zeppelins in particular:

‘As regards airships, or dirigibles, Germany has continued to be the greatest supporter of this variety of aircraft. While we have always held the view that dirigibles have certain well-defined uses, it would appear as if the war has demonstrated them to be outclassed by the heavier-than-air type of aircraft. Certain it is, that so far, despite all the efforts of the enemy to instil into the mind of the British public a fear and dread of their Zeppelins, the practical capabilities of these much vaunted airships have yet to be proved. That we are not sitting still to await the attack of these dirigibles may be accepted in advance, and it may be that if we are to be surprised by the Zeppelins, they on their part may find some even more startling surprises awaiting their coming than ever they can conceive. The Germans again have not been alone in their development of anti-aircraft guns, both France and this country being now well equipped in this direction, and ready to cope promptly with any attempt of invasion by air.’18

The First Lord of the Admiralty wrote a memorandum to the War Council on 1 January 1915, setting out his views on the level of threat posed by the Zeppelins:

‘Information from a trustworthy source has been received that the Germans intend to make an attack on London by airships on a great scale at an early opportunity. The Director of the Air Department reports that there are approximately twenty German airships which can reach London now from the Rhine, carrying each a ton of high explosives. They could traverse the English part of the journey, coming and going, in the dark hours. The weather hazards are considerable, but there is no known means of preventing the airships coming and not much chance of punishing them on their return. The unavenged destruction of noncombatant life may therefore be very considerable. Having given most careful consideration to this subject and taken every measure in their power, the Air Department of the Admiralty must make it plain that they are quite powerless to prevent such an attack if it is launched with good fortune and in favourable weather conditions.’19

A letter from Usborne dated 9 January 1915 has survived. It is addressed:

‘From Kingsnorth Air Station. To my dearest old chum. I just love marriage. I think Betty will have a baby in six months’ time. [Their daughter Ann was born in August 1915.] I have had a dull time recently, but this is nearly over, in another six weeks I hope to have newspaper cuttings for you. The Zeppelin effort is still to come. It may prove a fiasco, or it may prove fatal to us as a nation. Aeroplanes will do a lot more this summer.’20

Just over two weeks later, on 26 January, Usborne’s old airship, HMA No 2, was the last airship to fly out of Farnborough when all operations were finally moved from there to Kingsnorth. She never flew again, but her envelope would be put to good use in the development of one of the most numerous and successful of British airship types.

Kingsnorth was described by a young airship officer as:

‘Where intensive training was being given to the small band of budding airship officers, in both theory and practice, including gunnery and much drill. The long days were filled with lectures on aeronautics, navigation, engineering and meteorology, interspersed with the practical work of flying, rigging and engine overhaul.’21

The influence of the commanding officer is evident here; the training is focused on what is necessary to produce capable officers for the airship service and requires dedication and enthusiasm to shine. On 25 February, HMA No 8 resumed flying at Kingsnorth and entered service under the command of Flight Commander W.C. Hicks on 10 March, making a patrol of nine hours along the Sussex coast. Routine Channel patrols continued until 11 May, when it was replaced by HMA No 3. In April, Usborne would have no doubt witnessed a very tragic accident:

‘One of the air-mechanics – William J. Standford – attached to the airship station at Kingsnorth, Hoo, near Rochester, was killed on 23 April 1915 while assisting in mooring one of the naval airships. From the evidence at the inquest it appears that while being hauled down by a landing party, the airship was carried away by the wind, which was blowing at thirty miles an hour. All the men let go except Standford, who apparently thought the party would regain control. He was carried to a height of about 500 feet, and, after hanging on for nearly ten minutes, dropped to the ground and was instantly killed. Flight Lieutenant James William Ogilvy Dalgleish, RN, the commander of the airship, said that the man was about fifty feet from the ground when he first saw that he was on the rope. He immediately let out gas to get down, but the airship continued to rise until the rope was off the ground. The airship was rolling, which made it more difficult for Standford to keep on. She started to come down, and the witness hoped it would land in time, but Standford dropped off. A verdict of accidental death was returned.’22

HMA No 8 Astra-Torres at Kingsnorth in the spring of 1915. (Ces Mowthorpe Collection)

As for the airships Beta, Gamma, Delta and Eta – Eta was the first to go. On her way to Dunkirk on 19 November 1914, she flew into a snowstorm near Redhill, and, having made a forced landing, broke away from her moorings and was so badly damaged as to be incapable of repair. Gamma and Delta were both lying deflated at Farnborough at the outbreak of the war, and in Delta’s case the car was found to be beyond repair, so she was deleted. Gamma was inflated in January 1915 and was used for mooring experiments. Beta saw active service, as she was based for a short period, early in 1915, at Dunkirk on spotting duties, under the command of Wing Commander Maitland, with the Belgian artillery near Ostend. By May 1916 all had been deleted from the active list and scrapped.

The SS Class Airship

Usborne’s next important contribution was assisting with the design of the SS Class airship. After the repulse of the initial German advance and the establishment of a system of trenches running from Belgium to the Swiss border, the war in France had come to something of a stalemate. A decision was made to try and break the deadlock by the application of a change of tactics at sea. On 4 February 1915, a communiqué had been issued by the Imperial German Admiralty which declared:

‘All the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, are hereby declared to be a war zone. From 18 February onwards, every enemy merchant vessel found within this war zone will be destroyed without it always being possible to avoid danger to the crews and passengers. Neutral ships will also be exposed to danger in the war zone, as, in view of the misuse of neutral flags ordered on 31 January by the British Government, and owing to unforeseen incidents to which naval warfare is liable, it is impossible to avoid attacks being made on neutral ships in mistake for those of the enemy.’23

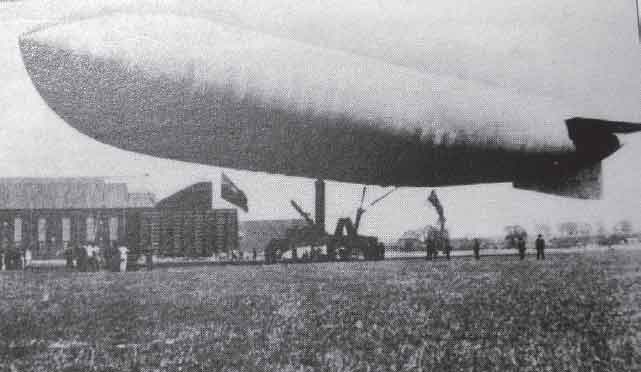

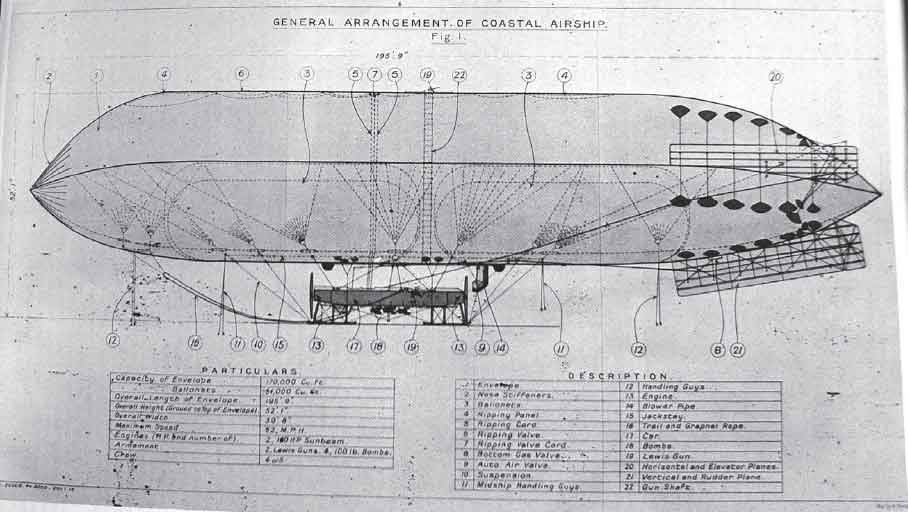

A plan of the SS-Class non-rigid airship.. (Via Patrick Abbott)

This declaration opened the first phase of what was to become known as unrestricted submarine warfare. Restricted submarine warfare had meant the U-boat would surface, warn its intended victim, give the crew time to abandon ship and then sink it. Neutral cargo ships and all passenger liners, probably even Allied ones, would be spared.

In order not only to prosecute the war and to supply its troops with food and munitions, but also to survive on the home front, Britain relied heavily on seaborne trade. If Germany could break, or even seriously disrupt, the flow of merchant vessels, then Britain’s ability to have waged war, or indeed feed its population, would have been rendered either difficult or impossible. This was the nature of the problem facing the Admiralty under the political direction of the First Lord, Winston Churchill. However, he recorded in his book, The Great War, the Admiralty was not too concerned at that stage. The Germans had moved too soon, there were simply not enough U-boats available in 1915 to make unrestricted submarine warfare any more than a considerable nuisance rather than a major threat. They compounded this error with a major miscalculation. On 7 May 1915, off the Irish coast, the British liner RMS Lusitania was sunk by a single torpedo fired at a range of 700 yards (640m) by U-20, commanded by Kapitanleutnant Walther Schweiger. The great ship was destroyed in a sudden violent detonation (it was carrying a secret cargo of shells, ammunition and explosives) which resulted in the deaths of nearly 1,200 of the 1,959 souls on board. Over 100 of the dead were American citizens and such was the outcry that the Germans prudently scaled down the unrestricted nature of the submarine campaign in order to avoid incurring greater wrath from the USA.

The pilot’s controls in a typical SS Class blimp. (Via Patrick Abbott)

[Author’s note: The distress signals sent from the Lusitania reached Queenstown; Vice Admiral Sir Charles Coke instructed the captains of all available vessels – all relatively small – to sail to the scene of the tragedy. They arrived two hours after the sinking. When they got there, they rescued any people still alive in the water and from only six lifeboats, which were all from the starboard side; 764 passengers and crew were picked up by boats from Queenstown. Many bodies were washed ashore along the coast and brought to the town for identification. The bodies of many of the victims were buried at either Queenstown, where 148 bodies were interred in the Old Church Cemetery, or the Church of St Multose in Kinsale, but the bodies of the remaining 885 victims were never recovered.]

To return to naval aeronautical matters, the Admiralty was not, however, unmindful of the potential threat posed by a greater submarine force. The professional head of the Royal Navy, the First Sea Lord, Admiral Lord Fisher, called a meeting at the Admiralty on 28 February 1915. He requested proposals to enhance the capability of the navy to provide surveillance and deterrence from the air. He had in mind a small airship type to the following specification:

(a) |

The airship was to search for submarines in enclosed or relatively enclosed waters. |

(b) |

She was to be capable of remaining up in all ordinary weather, and should therefore have an airspeed of 40 to 50mph (25 to 31kph). |

(c) |

She should have an endurance at full speed of about eight hours, carrying a crew of two. |

(d) |

She should carry a wireless telegraphy outfit with a range of 30 to 40 miles (19 to 25km). |

(e) |

She should take up about 160lbs (72kg) weight of explosives in the form of bombs. |

(f) |

She should normally fly at about 750 feet (238m) altitude, but be capable of flying up to 5,000 feet (1524m). |

(g) |

The design was to be as simple as possible in order that large numbers of these ships should be produced without undue delay. |

(h) |

An ample allowance of lift to be made for gas deterioration, so that each ship should remain in commission on one charge of gas as long as possible.24 |

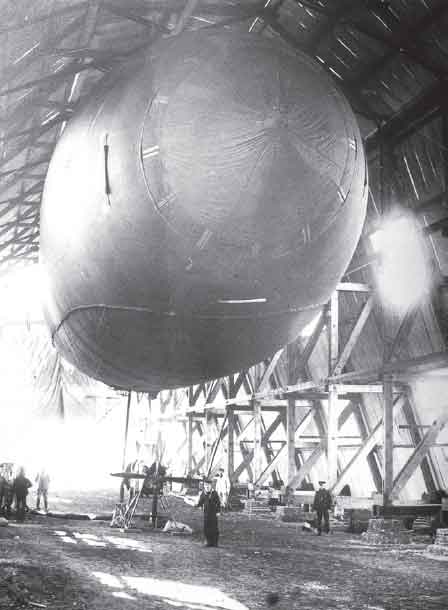

The unsuccessful SS-1. (Via Patrick Abbott)

In the words of the by then, Rear Admiral Murray Sueter, CB, MP, RN (Ret’d), in a deposition written in 1925 to the Post War Royal Commission of Awards to Inventors in respect of a claim made jointly with the Executors of the late Commander Neville Usborne, RN:

‘Lord Fisher summoned an important conference to consider the proposal of Mr Holt Thomas to build a large number of small airships for antisubmarine patrols. Until then the Admiralty Airship Officers could get practically no support. But with Lord Fisher’s powerful interest, airship work was given a new lease of life. Holt Thomas was given an order for a small airship of Willows design, and to compete with this, Commander Usborne was given instructions to develop a small envelope of 60,000 cubic feet (1,703 cubic metres) capacity. Captain Sueter consulted Commander Usborne and Commander Masterman, and suggested that as he had some BE2c aeroplanes that the pilots did not like because Commander Samson had sent in an adverse report about these machines, that the chassis of one of them should be tried with one of the old envelopes of the army airships. This was done with No 2 envelope I believe. The result of tests with this machine promised well and a two-ply envelope of 60,000 cubic feet (1,703 cubic metres) capacity was ordered from Messrs Shorts. As Shorts had expertise in balloons, Commander Usborne had to develop the whole of this envelope work. At first we had considerable trouble with the dope, because of very small holes in it, but Commander Usborne had developed Ioco dope for the first rigid and brought his great experience into play, and gradually the dope became so good that he managed in later airships to save much weight by using single ply fabrics, which were lighter than rubber proofed fabrics.

‘When the new Shorts envelope was fitted to a BE2c chassis it was christened SS-3 – Submarine Searcher No 3. The first experiment was SS-1, which was a failure due to the fact that the envelope was a poor holder of hydrogen. The Holt Thomas airship was SS-2 and comparative trials were carried out between SS-2 and SS-3. SS-3 – after some difficulty in determining the best position for slinging the car and the best position for fins and rudder – was an undoubted success. The government supplied airships of this type to France, Italy and the United States.’25

SS-2 at RNAS Capel in 1915. (Ces Mowthorpe Collection)

The Royal Commission of Awards to Inventors had been set up in 1919 and would sit for the next fifteen years reviewing 1,834 claims from those who considered that their ingenuity had contributed to the war effort in such a way as to be worthy of monetary recompense. A brief report in The Times26 notes that Sueter’s claim in this case was not successful. It is interesting to note that Vivian Usborne had been paid £6000 from the commission in 1920 for his work on mine defence equipment for ships, additional to £4800 from Messrs Vickers Ltd in respect of patent rights.

SS-3 on trials.. (Ces Mowthorpe Collection)

It is possible that Sueter may have been in error as regards some of the details. The airship authority, the late Ces Mowthorpe, stated in a conversation with the author that the competition was between the RN’s SS-1, which was indeed a BE2c fuselage attached to the envelope of HMA No 2, and the Holt Thomas SS-2. He adds that SS-3 was a production model which came later and served in the Dardanelles campaign. Be that as it may, the general points made by Sueter are not in doubt and are supported in an article written in 1934 by Air Commodore Masterman. He wrote:

‘The Airship Branch was threatened with disintegration, but revived when Fisher became First Sea Lord – Usborne came into his own. He devised, in conjunction with others, the SS Class. Kingsnorth became a factory or assembly place for small non-rigids under Usborne’s direction. In all, his influence was apparent, difficulties were overcome in a Napoleonic way, nothing was allowed to delay progress and many ingenious devices were adopted. Here, his driving force had full sway and an ideal outlet.’27

The official historian is succinct and to the point:

‘The idea seems to have been struck out during a conversation in the mess at Farnborough at which there were present the late Wing Commander N.F. Usborne, Flight Lieutenant T.R. Cave-Browne-Cave, and Mr F.M. Green of the Royal Aircraft Factory.’28

This statement is corroborated by one of Usborne’s contemporaries, who wrote that he went straight down to Farnborough after leaving the Admiralty to talk over the requirement with Cave-Brown-Cave and Green.29 According to another renowned airship historian it was a, ‘splendid improvisation.’30 Certainly Usborne had a very major role to play in sorting out what could have become a very serious problem. There was considerable difficulty in obtaining a sufficient supply of envelopes, as all the regular manufacturers were much too busy with aeroplane orders to accept any new orders. He made personal visits to six manufacturers specialising in waterproof clothing or rubber goods, described the exact requirement, placed the orders directly and arranged for experts from each of the companies to come to Kingsnorth for intensive tuition on the correct preparation of the material. There is no doubt that his efforts were appreciated by Murray Sueter, who wrote that he was placed in charge of all the envelope work, as he had done such good service with the Mayfly’s gasbags and outer cover.31

The peril in which the Airship Branch then stood is highlighted by a minute from the First Lord of the Admiralty dated 18 January 1915:

AIRSHIPS AND AEROPLANES.

Secretary.

First Sea Lord.

Fourth Sea Lord.

Director of the Air Division.

18 January 1915.

The general condition of our airship service, and the fact that so little progress has been made by Vickers in the construction of the rigid airship now due, makes it necessary to suspend the purely experimental work in connection with airships during the war, and to concentrate our attention on the more practical aeroplane, in which we have been so successful.

1. The Director of Contracts should, in conjunction with the Director of the Air Division, make proposals for suspending altogether the construction of the Vickers rigid airship. The material which has been accumulated should be stored, and the shed in which it is being constructed should be thus set free.

2. The repairing staff of the airships, which is now at Farnborough, should be moved with the utmost despatch to Barrow, and should be accommodated in the neighbourhood of the new rigid airship shed and make the shed their repairing shop. Arrangements should be made to this effect with Vickers, so that we take over this shed completely from them during the war.

3. The Farnborough sheds are to be handed back to the army as soon as possible, thus meeting their urgent demands.

4. Messrs Vickers are to be urged to expedite as much as possible the two non-rigid airships they are building in the old Admiralty shed at Barrow. These, when completed, will give us five airships – three Parsevals and two Astra-Torres, besides the small military ones. These five airships will be accommodated, three in the wooden shed at Kingsnorth and two in the old Admiralty shed at Barrow. The iron shed at Kingsnorth will thus become available for the large numbers of aeroplanes which are now being delivered. All necessary steps must be taken to enable aeroplanes, in skilful hands, to alight or ascend from the neighbourhood of Kingsnorth.

5. Temporary housing accommodation for the aeroplane staff is to be at once provided near Kingsnorth, which is to become an aeroplane as well as an airship base.

6. The personnel of the Royal Naval Airship Service are to be reduced to the minimum required to man and handle the five airships. The balance, including especially the younger naval officers, is to be transferred to the aeroplane section. The military officers are to remain with the airships. I am not at all convinced of the utility of keeping this detachment at Dunkirk, and unless they are able to show some good reason for their existence they should be withdrawn.

W.S.C.32

The success of the RNAS blimps later caused him to change his mind when he wrote his four volume history of the war:

‘Had I had my way, no airships would have been built by Great Britain during the war (except the little blimps for teasing submarines).’33

The SS Class was a fairly simple and basic design, but it had several merits. The production model met the specification as regards speed, 40–50mph, and endurance, 8–12 hours. It could climb with its crew of two to a height of more than 5000 feet. It was also cheap – with a unit cost of £2500. The shape was reasonably streamlined, being blunt at the nose but tapering towards the tail. The gasbag had a capacity of 60,000 cubic feet and was 143 feet 6 inches in length, with a maximum diameter of 27 feet 9 inches. [As a comparison this is about twice the length of a Short 360.] The two internal ballonets mounted fore and aft not only ensured that the envelope kept its shape, but could also be used by the pilot to adjust the airship’s trim. They were inflated by means of a metal scoop mounted to catch the slipstream of the propeller. Two non-return valves made from fabric, the ‘crab-pots’, controlled the flow of air into and out of the ballonets. The gross weight which the airship could lift – including its own structure – was 4180lb, which gave a net lift available for crew, fuel, ballast and armament of 1434lb. The disposable lift with a crew of two on board and full fuel tanks was 659lb. The envelope was made of rubber-proofed fabric, reminiscent of an old-fashioned mackintosh. It consisted of four layers, two of fabric, with a layer of rubber in-between and on the inner surface. At the tail of the gasbag a single vertical fin and rudder were fitted ventrally, while horizontal fins and elevators were affixed to port and starboard.

To make them completely gastight and protected from the ravages of weather, saltwater and sun, four coats of dope were applied to the outer surface, with a top coat being of aluminium varnish. The BE2c fuselage was retained, stripped of its wings, rudders, elevators and eventually wheels, axles and suspension.

Propulsion was by means of a 75 hp air-cooled Renault engine driving a large four-bladed propeller. The observer, who also operated the wireless set, sat in the front seat, with the pilot behind him. It was powered by two four-volt accumulator batteries rather than by fitting a generator driven by the engine. This had two advantages; it was lighter and would still operate in the event of an engine failure. Communication was by means of Morse code. The wireless telegraphy receiver and Type 52 transmitter had a range of between 50 and 60 miles, when flying at not less than 800 feet. A long trailing aerial, some 200 feet in length, with a lead weight on the end to keep it from fouling any part of the airship, was wound down from a reel fitted to the side of the car. Small bombs, eight 16lb or two 65lb and a Lewis machine gun, could be carried by way of armament. A lever bombsight was fitted and the release was operated by Bowden wire control. It was considered to be capable of being flown by a young midshipman with small-boat training. To this end, junior officers were brought in from the Grand Fleet by means of ships’ captains being asked to select one of his midshipmen who was willing to volunteer for special temporary and hazardous service. One of these was Thomas Elmhirst, from the battlecruiser HMS Indomitable, whom we shall meet shortly. Enthusiastic, young, direct entry civilians were also induced to join up – specifically for this purpose. An intensive training course at Wormwood Scrubs, lasting about a month, was given in the theory of aerostatics (aeronautics, navigation, meteorology, engineering, rigging and engine overhaul), practical balloon flying and mastering the controls of a small airship. The training balloons all had girls’ names such as Joan, Alice, May and Hazel. Normally their baskets could carry up to five trainees and an instructor. The young officers greatly enjoyed the balloon flying, eight qualifying flights – six under instruction (including a night flight), one trip as second in command and finally, a solo. Elmhirst’s solo was in Suffolk, when the only difficulty encountered was after landing in a thorn hedge and an inquisitive local with a smoking pipe in his mouth began to closely examine the gas valve aperture. He was dissuaded from this dangerous practice very quickly.

Admiral Fisher demanded that forty more of these small airships should be produced as expeditiously as possible. Neither the First Sea Lord nor the First Lord were to remain at the Admiralty long enough to see the SS Class into operation. In May, following the tragedy of the Dardanelles Campaign, Winston Churchill resigned and Jackie Fisher also departed. They were succeeded by the former Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour and Admiral Sir Henry Jackson, respectively.

It is hard to imagine now just what it would have been like for the crews of the Submarine Scout airships, suspended in an open cockpit, between a few hundred and a few thousand feet above the cold, grey sea, making slow headway against the wind. Luckily two such pilots recorded their impressions. Air Marshal Sir Thomas Elmhirst recalled his experiences as a young pilot of only nineteen years of age:

‘I controlled height by means of a wheel in my right hand linked by wires to elevator planes stuck on the after end of the gasbag, and direction by foot pedals, again connected by wires to a rudder at the after end of the gasbag. My other controls, to be operated by the left hand, were the engine, the gas valve, two ballonet air valves and an air pressure control cable. I had a red cord to rip the top off the gasbag in case of a forced landing and a handpump to top up the main fuel tank under my seat from the gravity feed tank for the engine. I had made a wooden bombsight – quite simply two nails as foresight and backsight, the foresight being moveable to a scale marked with the speed of approach, 20 to 50 knots. My other instruments were mounted on a board to the front of the cockpit – a watch, airspeed and height indicators, an engine revolution counter, an inclinometer, gas, oil and petrol pressure gauges, and a glass petrol level indicator. These all had to be monitored closely. Provision was made for illuminating the instruments by four small bulbs. Navigation was by means of chart and floor-mounted compass. A map case with a celluloid front formed the door to a small cupboard.’34

Whilst doing all of this, he also had to pass messages back and forth to his wireless operator, read his maps, take compass bearings, plot his course, and at the same time keep a constant watch on the sea below. It should be noted that conditions were cramped and confined on board, exposed to the cold and at the mercy of the elements – the speed through the air of these craft could be reduced to only a few knots when flying into a headwind. This would not be a pleasant experience when returning from a long patrol – tired, hungry and cold. Another airship pilot of the period, T.B. Williams, wrote:

‘As the pilot could not leave his little bucket seat during a flight of often many hours duration, he just didn’t get a meal. It was also difficult to answer the call of nature. I evolved an arrangement made up from a petrol funnel to which was attached a piece of rubber hose passing to a watertight junction in the hull under my seat. The petrol funnel was hung on a brass cup hook near my elbow. I had some difficulty in inventing a purpose for this gadget when explaining the instruments and controls to the wife of a VIP on one occasion.’35

There is no doubt that Neville Usborne’s drive, imagination and technical knowledge were of considerable importance in the rapid design and production of this exceptionally useful weapon which helped to win the first U-boat war. His estate later made two specific claims regarding the design of the SS Class – the rigid umbrella nose frame, which helped maintain the shape of the gasbag, and the ‘crab pot’ system, which diverted air from the propeller’s slipstream through a non-return valve to keep the internal ballonets charged, and so retain the shape and trim of the airship.36

The intent with the SS Class airships was to guard the eastern entrance to the English Channel with stations at Capel, near Folkestone, and Polegate, near Eastbourne, and the Irish Sea to the north and the south from bases at Luce Bay in Wigtownshire and the Isle of Anglesey. Bases were then added at Mullion in Cornwall and Pembroke in Wales. They operated from four locations in Ireland; Ballyliffin, Co Donegal; Bentra, Co Antrim; Johnstown Castle, Co Wexford and Malahide Castle, Co Dublin. Bentra and Ballyliffin were sub-stations of Luce Bay; an airship shed and supporting huts were erected at Bentra. Johnstown and Malahide were sub-stations of Pembroke and Anglesey respectively, neither had a hangar.

SS-23 approaching to make a landing at Luce Bay. (Via Donnie Nelson)

The SS Class were simple to fly and easy to produce in the numbers required at short notice. They were fairly crude designs and the engines were somewhat unreliable, but they provided the air cover needed when no other type of aircraft could have done so within the necessary timescale. An experienced airshipman of the period wrote:

‘At that time no aeroplane could carry out flights of eight, ten or more hours, as we did regularly – nor did we need a prepared aerodrome. Flights were possible in all but the very worst weather conditions. Fog did not stop us flying. In favourable weather we could land gently into the hands of a few men comprising a landing party. In unfavourable weather we could land by trail rope. Night flying was a little more difficult than by day and no elaborate landing lights were needed. I once landed in a flat calm, by the light of matches, and at best we only had a few oil flares to guide us.’37

They also gave a new generation of naval airshipmen a wealth of practical experience, so preparing them for the command of the larger and more capable non-rigid airships which were to follow.

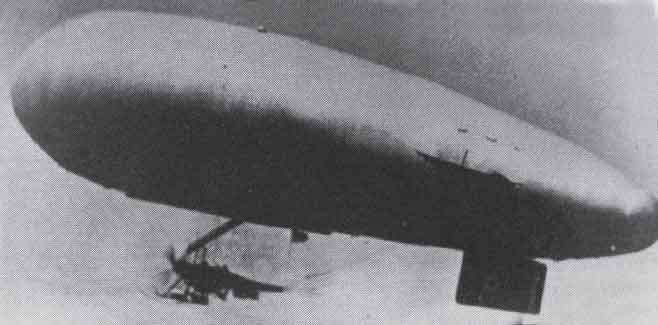

The Coastal Class Airship

As the activities of the U-boats grew, more extended cruises were required, and according to Murray Sueter, Usborne suggested using the Astra-Torres patents and building 180,000 cubic feet (5109 cubic metre) airships which would have greater range than the SS Class and moreover would benefit from twin-engine reliability. Sueter agreed and indeed claimed to have invented the double-ended car as used in these larger airships – named Coastals. He also wrote that he developed the 150 hp (111 kW) Sunbeam for seaplane work and recommended placing a Sunbeam engine at the end of each car. Later, further improved airships resulting from the Coastal design were the Coastal Star and North Sea types. In 1925 he wrote:

‘Admiral Sueter desires to place on record his high appreciation of the hard work and devotion to the airship cause displayed by Commander Usborne. Far into the night and the early hours of the morning, this scientific officer worked to make these airships a success and due to him in large part their wonderful success was due.’38

A plan view of a Coastal Class airship.

The Coastal design was indeed based on the Astra-Torres tri-lobe envelope, all connected by porous internal curtains, with four ballonets fitted in the lower lobes, and was developed by the design team at Kingsnorth. The envelope used was that of HMA No 10 and the control car was produced by adapting the fuselages of two Avro 510 seaplanes to produce a push-pull, twin-engine layout. The prototype was named the Yellow Peril because of the chrome yellow dope used on the envelope. There was a problem with the dope and air bubbles as it was applied to the fabric, which was sorted out by Usborne’s ingenuity.39 C1 flew for the first time on 26 May 1915. The production of thirty was agreed on 19 June 1915. The first production airship flew at Kingsnorth in September 1915 and was ready for service in the spring of 1916. It proved to be a very valuable workhorse for the RNAS lighter-than-air division, with its capacity to carry a crew of four or five, a wireless set, two Lewis guns, nearly half a ton (500kg) of bombs or depth bombs, an endurance of up to 22 hours and a maximum speed of 52mph (83kph).

A Coastal Class airship on patrol.

Later in the war Tom Elmhirst was the captain of C19 and described his service at Howden in Yorkshire as follows:

‘Weather and serviceability permitting, C19 was seldom off patrol. Dispatched at dawn and told to stay on patrol for at least twelve hours was hard going. Hard on the eyes, watching the gasbag pressure, watching the course the coxswain was steering and one eye all the time looking for the enemy – whom I never saw. He could see me from twenty miles distant and submerge. I could only hope to catch sight of a periscope 400 yards away. It was hard on the hands and I came home with blisters from the elevator control wheel after a “bumpy” day, also hard on the backside sitting concentrated for long hours. Food was a pleasant relief and a problem. It did not always taste well in the slipstream of an open-exhaust engine using castor oil! I eventually settled for a large packet of marmalade sandwiches and a bottle of Malvern water. My crew and I did not smoke or “drink” in the air, but just looked forward to a cigarette and a beer on landing.’40

Before leaving Kingsnorth, Usborne made significant input to an 80-page report which would be issued by the Director Air Services in December 1915, which would give a highly detailed account of: ‘The Experimental Work in connection with Airships, Balloons and Kite Balloons from November 1914 to November 1915’, firstly at Farnborough and then, from March 1915, at Kingsnorth.

The Zeppelin Menace

Meanwhile, on 13 August 1915, Usborne was appointed Inspecting Commander of Airships (Building) at the Admiralty. His restless mind was continually occupied by the aeronautical requirements of the war and looking beyond his own immediate task, focussing on the problem of how to increase the range of British aeroplanes and how they would be best used after the end of the war.

Usborne’s most pressing task, later in 1915, was to draw up schemes to combat the Zeppelin menace. As the RFC was fully stretched in providing support to the BEF in France, it had been agreed in September 1914 that the air defence of Great Britain should be the responsibility of the Admiralty rather than the War Office.

‘On 3 September, Lord Kitchener asked me in cabinet whether I would accept, on behalf of the Admiralty, the responsibility for the aerial defence of Great Britain, as the War Office had no means of discharging it. I thereupon undertook to do what was possible with the wholly inadequate resources which were available.’41

Since the early experimental days in the first decade of the twentieth century, Zeppelins had been developed considerably in reliability and carrying capacity. Between 1910 and 1914, the Zeppelin Company had established the first scheduled commercial airline, DELAG, (Deutsche Luftschiffahrt Aktien Gessellschaft) with passenger airships including LZ6, LZ7 Deutschland, LZ8 Deutschland II, LZ10 Schwaben, LZ11 Viktoria Luise, LZ13 Hansa and LZ17 Sachsen, offering short haul air tours in Germany. At first it was a modest success at best, but with Dr Eckener as Flight Director it was established on a much sounder basis by greater emphasis being placed on crew training, ground handling, engine performance and reliability, and weather forecasting. He summed up the achievement as follows:

‘More and more we learned to overcome our difficulties by making proper arrangements and developing a sure skill. The DELAG fulfilled its main purpose, which was to train a nucleus of qualified commanders and steersmen, and above all to develop a familiarity with the elements in which the craft had to fly in the ocean of the air, with all its dangerous tricks. The DELAG became the university of airship flight.’42

A total of 34,028 passengers were carried in more than 2000 flights, with a total distance covered of more than 100,000 miles (160,900 km) and an excellent safety record. One airship alone, the Viktoria Luise made a total of 1000 trips between Hamburg, Heligoland and Copenhagen in the years 1912–14. As has been noted, the War Office in London was slow to appreciate the potential of aerial warfare, noting in 1910 that it was; ‘Not convinced that either aeroplanes or airships will be of any utility in war’ and that it seemed unlikely that it would be possible to, ‘arrest or retard the perhaps unwelcome progress of aerial navigation.’43 It is of interest to note that the Admiralty’s attitude to the introduction of steamships some 100 years before was similarly unwelcoming; ‘Their Lordships felt it their bounden duty to discourage to the utmost of their ability the employment of steam vessels, as they consider that the introduction of steam is calculated to strike a fatal blow at the naval supremacy of the Empire.’44

The Imperial German Navy’s Airship Division was formed in 1912 with the plan to take the war to the enemy by means of a bombing campaign. The first naval Zeppelin was the LZ14, which was commissioned into service as the L 1. It was lost at sea the following year; among those killed was the senior officer of the Naval Airship Division, Korvettenkapitän Metzing. His replacement as commanding officer was Korvettenkapitän Peter Strasser, who was convinced that the Zeppelin was a strategically important weapon which could make a real difference to winning the war, saying that Britain could be defeated: ‘Overcome by means of airships, through increasingly intensive destruction of cities, factory complexes, dockyards….’45

Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke, the Chief of the German General Staff from 1906 to 1914, believed that Zeppelins possessed potent possibilities, as also did the German aviation press. On 24 December 1912 he advised the War Ministry that:

‘In the newest Zeppelins we possess a weapon that is far superior to all similar ones of our opponents and that cannot be imitated in the foreseeable future if we work energetically to perfect it. Its speediest development as a weapon is required to enable us at the beginning of a war to strike a first and telling blow, whose practical and moral effect could be quite extraordinary.’46

In 1914, the Zeppelin represented a threat, with a payload of 500lbs (227kg) of bombs, at a time when fixed-wing aircraft were deemed suitable for unarmed reconnaissance only. It was also an unknown quantity with all the fear that such a novelty would bring. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, was more sanguine, stating in his speech following a banquet at the Mansion House on 5 May 1913:

‘Any hostile aircraft or airships which reached our coast during the coming year (1914) would be promptly attacked in superior force by a swarm of very formidable hornets.’47

Hornets would indeed have had to do the job, as there was a distinct lack of suitable aircraft. Indeed, when Flight Sub-Lieutenant Eric Beauman reported for duty with the RNAS Air Defence Flight at Hendon in September 1914, he was somewhat disquieted to discover that there was one aircraft and one pilot (himself) allocated for the aerial protection of London.48

However, at this early stage of the war, neither the German Army nor the Imperial Navy had an abundance of airships available for service. The army had six Zeppelins and one wooden-framed Schütte-Lanz type. Three of these were lost in ill-advised missions in support of the invading troops in the initial war of the frontiers. The navy had only one operational airship, which was fully tasked with reconnaissance for the High Seas Fleet.

The Schütte-Lanz Airship Company had been founded in 1909 by Dr Johann Schütte and Dr Karl Lanz with the backing of a group of industrialists. Its growth had been encouraged by the army, perhaps to provide a counterweight to the Zeppelin monopoly. Some twenty of these had been constructed in equal number for the army and navy before the end of the war. The laminated plywood used was successful only up to a point. It was undoubtedly lighter than metal, but beyond a certain size lacked sufficient strength. Moreover, a nautical environment was particularly unforgiving. In the words of Peter Strasser: ‘Most of the Schütte-Lanz ships are not usable under combat conditions, especially those operated by the navy, because their wooden construction cannot cope with the damp conditions inseparable from maritime service.’

The first city to be bombed by a Zeppelin was Antwerp on 24–25 August 1914, where twenty-six citizens were killed. Shortly afterwards, three Zeppelins were in action on the Eastern Front, bombing the town of Mława on the Russo-Prussian frontier. That autumn, the citizens of London were subject to air raid precautions for the first time, with street lamps being extinguished and a blackout being imposed. It was defended by a handful of guns that had been modified to fire at a higher angle, searchlights were ordered and training in night flying was recommended – though the few available aircraft had neither the speed, climb rate, nor weapons, to be a credible counter to any marauders. A Zeppelin could climb at 850–1000 feet (260–300m) a minute, whereas a BE2c took an hour to reach the Zeppelins’ cruising height of 10,000 feet (3004m). One of the finest of Zeppelin commanders, Kapitan-Leutnant Heinrich Mathy of the Imperial German Navy commented:

‘As to an aeroplane corps for the defence of London, it must be remembered that it takes some time for an aeroplane to screw itself up as high as a Zeppelin and by the time it gets there the airship would be gone.’49

The raiders did not come in late 1914 and a false sense of security developed. Aggressive countermeasures were taken, however, by the RNAS, bombing Zeppelin sheds at Düsseldorf and Friedrichshafen. The Kaiser hesitated to attack, for he was fearful of the effect that such an unprecedented form of warfare would have on neutral opinion.

In early 1915, with nine newly constructed Zeppelins ready for action, he gave qualified approval for attacks on military targets only – a somewhat futile gesture, as bombs could not be dropped with such a degree of accuracy. Accurate navigation by night was very difficult, compounded by the fact that the airships’ commanders were reluctant to use the radio navigation aids available in case they revealed their position to the enemy. They were also highly subject to the weather conditions – heavy cloud, strong winds or storms, made missions impossible and they were not usually able to find out what weather they would encounter over England until they got there. The initial Zeppelin raids across the North Sea were made in January 1915 to King’s Lynn and Yarmouth, and were followed by an attack on Tyneside, the Humber area and East Anglia in April. In May, the German High Command ordered that Zeppelin raids should aim to bomb Britain into submission. London and Southend were attacked in May, Hull and Jarrow in June, London again in September and October. A total of over 200 civilians were killed and more than 450 injured in twenty-three successful, or attempted raids, during 1915. There was also considerable damage to property, but of even more value were the psychological effects and the defensive efforts which had to be diverted from other theatres (eventually some 17,000 officers and men were employed on AA defence in the UK). The public demanded a visible response, and a degree of hysteria and xenophobia was whipped up by the press, with headlines such as; ‘The Coming of the Aerial Baby-killers.’50 Reaction in German newspapers was understandably different:

‘The most modern air weapon, a triumph of German inventiveness and the sole possession of the German forces, has shown itself capable of carrying the war to the soil of old England.’51

Indeed, a naval air service contemporary of Usborne’s did not believe that the Germans were deliberately aiming to kill civilians:

‘Most of us believed that the Zeppelins set out to bomb military targets, only bombing open towns and villages as a result of losing themselves in the dark.’52

It is certainly true to say that they did not want to believe that the German naval officers, with whom they had been on excellent terms at far flung stations all around the world in the long years of peace, could be capable of wilful atrocities. Whatever the case, there had to be a concentrated effort to find an effective solution and it was this problem that Usborne attempted to resolve. In October 1915, he wrote a paper on Anti-Zeppelin Defence, which he submitted to his superiors in the Admiralty, reviewing current proposals for defensive measures.53 The first involved stationing balloons all over London, each fitted with a car containing two men and a Davis, 6-pounder, recoilless gun. These would be capable of ascending to 12,000 feet (3657 metres) inside six minutes. When a Zeppelin was spotted all the balloons would be released and the nearest one would engage the intruder. His recommendation was to carry out a trial of the installation. The second idea was to use a balloon to lift an aeroplane to patrol height. The aircraft would only be slipped from the balloon if a Zeppelin was spotted, otherwise it would simply descend by gently deflating the envelope. The third was to moor an armed kite balloon at a similar altitude to the ceiling of the massed balloons. He regarded this as being the most technically challenging and costly plan. A fourth notion was to suspend nets over London by means of balloons, which was dismissed as totally impracticable. The fifth was a design which would become known as the Airship Plane and which will be discussed in more detail below. The final scheme was an aerial torpedo carried by a model airship, released from the ground and directed, ‘by W/T or other suitable means.’ To this end experiments with sound detection and radio control were in progress. A few months later, in January 1916, just as the Germans were resuming raiding following a suspension forced on them by the winter weather, Usborne received a letter from Vickers comparing the weight, horsepower, maximum rate of climb and maximum/minimum speed of a range of aircraft:

Scout – 1000lbs, 110 hp, 7000 ft/8 ½ min, 118–50mph,

Fighter old – 2200lbs, 110 hp, 300 ft/7 ½ min, 72–42mph,

Fighter new – 2200lbs, 110 hp, n/k, 85–45mph,

2 engine fighter – 2800lbs, 2x110 hp, n/k, 105–40mph,

New big – 20,000lbs, 1000 hp, 3500 ft/9 min, 95–45mph54

None provided the perfect answer to getting explosive material quickly enough and closely enough to the Zeppelin’s gasbag to detonate the highly volatile hydrogen it contained, as Flight Sub-Lieutenant Rex Warneford had proved on 7 June 1915 when he destroyed LZ37 over Ghent by bombing it from his Morane Parasol. Captain Sueter’s satisfaction with Warneford’s success was tempered by a summons to a meeting with three Sea Lords. Instead of receiving congratulations on behalf of the work of one of his young officers, he was taken to task for permitting sub-lieutenants to go to music halls at night while under training to become SS Class airship pilots.55

LZ37, which was destroyed by Flight Sub-Lieutenant Rex Warneford.

How was the problem to be solved of an aircraft attaining height rapidly enough to be able to attack a Zeppelin successfully on a regular basis? Moreover, could an aircraft be given the longer endurance required to patrol at height and so intercept an enemy airship? Usborne’s fertile brain devised a solution which has been described by the airship author and expert Ces Mowthorpe as a brilliant concept – suspending a complete BE2c from an envelope similar to that used by the SS type airship. The idea of the Airship Plane was that it could patrol as an airship and then, on spotting the Zeppelin, the aircraft section could be slipped to intercept, while the gently deflating envelope made its way slowly to earth. In a letter to Admiral Fisher, Usborne wrote:

‘It is recognised that an aeroplane, once it gets above a Zeppelin, can destroy the latter without great difficulty. On the other hand, it is recognised that for an aeroplane, flying at night is almost too dangerous to be practical as a routine, also, that the rate of climb of an aeroplane is so slow that it cannot reach the altitude of a Zeppelin in the time available. The idea is to substitute a complete aeroplane for the car normally carried by a small airship. This aeroplane will be attached in such a way as it can slip itself from the envelope once it has established itself above the Zeppelin.’56

And in his report, written in October, he had remarked:

‘This is obviously the most completely satisfactory proposal of all. The problem has been worked at, on various lines, for some three months. A successful result is confidently anticipated in the course of a few weeks more.’57

He also believed that the idea could have offensive possibilities, increasing the range of bombing aircraft which could be detached from the mother airships over the target.

The Airship Plane was flown without separation by Flight Commander W.C. Hicks in August 1915 and the first release, without a crew, was also successful. On 19 February 1916, permission was given for a manned slipping trial, with the pilots being given a completely free hand to choose their day and time, with an unknown staff officer adding in his advice to the Director of the Air Service, Rear Admiral Charles Vaughan-Lee:

‘I regard it as most inadvisable to allow the trial to take place in front of important visitors, as their presence necessarily exercises a certain compulsion on the pilots, and, in case of accident, the impression created is very undesirable. On this subject of experimental work I have some knowledge and never allowed any submarine trials to be undertaken other than in secret. It is difficult to carry out aircraft trials in secret, but as much secrecy as possible is most desirable.’58

Therefore, on 21 February, Usborne and Squadron Commander Wyndor Plunkett de Courcy Ireland (the CO of the Great Yarmouth Air Station, who had been born in Co Tipperary in 188559) ascended from Kingsnorth on the manned trial of the AP-1. The craft climbed in a series of circles to about 4000 feet (1219m), watched by an anxious group of officers below. The AP-1 exceeded its equilibrium height, causing a drop in gas pressure, and the instability thereby created resulted in the premature detachment of the forward suspension cables. The nose of the aircraft plunged downwards, overstressing the remaining two wires, which failed. Apparently, Ireland had tried to climb along the fuselage to release the remaining cables, but to no avail. The controls of the BE (Serial No 989) were in all probability damaged as it parted company from the envelope, so making a safe descent impossible. The BE section was seen to sideslip and turn over, throwing out Ireland, who fell into the River Medway and was drowned. Usborne remained with the BE, which crashed in Strood Railway Station goods yard. It is poignant to think that their lives could possibly have been saved had the parachute demonstrated at Kingsnorth some eighteen months before been adopted, particularly for test crews and other high-risk ventures. The Admiralty immediately banned any further experiments of this nature until one of the new rigid airships should become available, and the planned AP-2 never flew. To the modern mind the Airship Plane seems something of an outlandish conception. But yet, was it any odder at that stage in its development than another idea which had, in its early days, been given considerable support by figures such as Winston Churchill and Murray Sueter? It was a large, ungainly steel box which lumbered across the ground on cumbersome treads at a speed far less than that of a walking man. Its crew were subject to deafening by the noise of the unenclosed engine with which they shared a cramped compartment, par-boiled by the intense heat which it gave off, and semi-asphyxiated by the pungent fumes of its exhaust, with guns firing from its barbettes like a turn-of-the-century armoured cruiser. It was, of course, the tank, which in the end would prove a most useful battlefield asset.

The AP-1 at Kingsnorth. (J.M. Bruce; G.S. Leslie Collection)

The AP-1 in flight at Kingsnorth in 1915.

A Court of Inquiry was held, but the record of its deliberations and verdict does not appear to have survived, apart from some fragments of commentary upon it, made in March 1916.60 It is addressed ‘Admiral’ and is unsigned, but concludes:

‘I cannot speak too highly of Commander Usborne’s and Lt Commander Ireland’s sacrifices. They were trying to evolve a machine that could compete with Zeppelins and they gave their lives in this endeavour. Regarding paragraph 8 of the finding, it is submitted that these two gallant officers be given some post-mortem honour.’

Air Commodore Masterman wrote in 1934:

‘Thus fell two gallant men, giving their lives for an experiment which since, under different conditions, had proved to be practicable, mourned by all who had the privilege of knowing them. As far as Usborne is concerned no one can talk of early British airship days without mention of his name and work, and no one can say what the subsequent history of this service would have been, had he been spared to assist in its development. A personality was lost on that February day which was irreplaceable.’61

Masterman, who knew Usborne so well, and would later be instrumental in founding the Royal Observer Corps, lived to the age of seventy-seven, passing away in 1957.

Betty Usborne had a dream three nights beforehand – a black car from the Admiralty had drawn up at the door of their house in South Kensington to tell her of Neville’s death. On waking she asked him to postpone the test. He wouldn’t. When the day came she determined to stop the dream coming true by leaving with him first thing and not returning till after midnight. But at midnight the black car was waiting. A fellow airshipman at Kingsnorth, Commander Harold Woodcock, wrote to Mrs Usborne:

‘He was a man of vast ability, energy, initiative and fearlessness, his death is a great blow to the service; we shall all miss his personality and genius more than I can say.’62

Another contemporary described him as; ‘The brilliant experimental non-rigid pilot.’63

The Official Historian wrote of him:

‘Commander N.F. Usborne, whose tenacious ability had done much to sweep aside the difficulties and prejudices that dogged the early development of the small airship, typifies the vision and courage which the personnel brought to their work. The science of aeronautics was young. Ideas which seemed to work out in theory had always to stand the ultimate practical test in the air. The risk in this, the supreme test of the inventor’s faith in his machine, had to be accepted, not in the excitement of battle, but in cold blood.’64

Betty, who married Hugh Godley, later the second Lord Kilbracken, died in 1958, and Ann, who never married, passed away in 1985. Betty’s son, John Godley, later the third Lord Kilbracken, and a distinguished Fleet Air Arm pilot in the Second World War, wrote:

‘As her second marriage disintegrated, she increasingly idealised her first husband, Neville. Their years together (at least in recollection) had been so perfect, the gentle lover, the wise father, the brilliant man of invention. He was more than an outstanding naval officer, a visionary with an eager mind, as well as great charm and magnetism.’65

Her father, the artist Vereker Hamilton, died in 1931 and his obituary in The Times noted that his painting, The Airship Flown by Captain Neville Usborne, RN, was held in the collection of the Imperial War Museum.66

The Zeppelins were eventually defeated by interceptor aircraft armed with a machine gun firing a mixture of explosive ammunition to punch holes in the fabric covering the outer skin and the gas cells within, and incendiary bullets to ignite the escaping gas, anti-aircraft fire from the ground and their own inherent unsuitability for the role of strategic bombing. Almost 100 Zeppelins and Schütte-Lanz airships served with the German Army and Navy during the war. Nearly three-quarters of these were lost due to being shot down, bombed in their sheds, catching fire accidentally, being wrecked by heavy landings, or succumbing to adverse weather conditions. They made 4720 operational flights covering over 1,250,000 miles (2,000,000 kilometres), dropping just 202 tons (203 metric tonnes) of bombs, which resulted in the deaths of 556 and injuries to 1358 more.67 Of the navy’s seventy-three ships, no less than fifty-three were destroyed and forty per cent of the crews were killed – a loss rate comparable to those sustained by the German U-boat Service and the RAF’s Bomber Command in the Second World War.68 Murray Sueter calculated that the RNAS, RFC and RAF were directly responsible for the destruction of twenty-one enemy airships, with the BE2c taking part in nine of these.69 The German airships totally failed to live up to either the expectations of their operators, or the fears of the countries against which they were directed. It is arguable that they could have been put to better use on long-range reconnaissance missions, scouting for convoys and passing information by wireless to shore bases or U-boats. Undoubtedly they were of considerable assistance when used by the High Seas Fleet for scouting, carrying out more than 200 such missions over the North Sea and may well have saved it from destruction at Jutland. Indeed, Admiral Jellicoe later wrote that:

‘Our position must have been known to the enemy, as at 2.50am, the fleet engaged a Zeppelin for quite five minutes, during which time she had ample opportunity to note, and subsequently report the position and course of the British Fleet.’70

Taken as a whole, however, the Kaiser’s rigid airships were a costly flop in comparison to the much simpler and cheaper Royal Navy non-rigids, which carried out a valuable but unheralded service throughout the war.

In 1921, the Royal Aeronautical Society founded the Usborne Memorial Prize for a lecture on an airship subject, in memory of Wing Commander Neville F. Usborne. Indeed, the Secretary of the RAeS, Lieutenant Colonel W. Lockwood Marsh, wrote to The Times suggesting that Usborne’s name be coupled with that of Air Commodore E.M. Maitland, who had recently lost his life in the R.38 airship disaster.71 The terms of the award were subsequently changed to:

‘Awarded annually – at the discretion of the council – for the best contribution to the society’s publications written by a graduate or student on some subject of a technical nature in connection with aeronautics.’

The revised terms were similar to another of the Royal Aeronautical Society’s awards, the Pilcher Memorial Prize. The two were subsequently amalgamated to become the Pilcher-Usborne Award, which was awarded through to the late 1980s.

In the papers which have survived are some unfinished report forms on the fifteen officers at RNAS Kingsnorth, which Usborne was probably working on before his final, fatal flight. His concise, no-nonsense summaries are a mark of the man and may serve as an epitaph:

W.C. Hicks – ‘A good common-sense officer. Not much ingenuity or initiative.’

J.N. Fletcher – ‘A very intelligent, keen officer. Has a somewhat unfortunately brusque manner.’

A.D. Cunningham – ‘An excellent messmate.’

J.W.O. Dalgleish – ‘This officer has a tendency to become depressed and grumpy.’

E. Sparling – ‘An indefatigable and reliable officer. Has the gift of instantly establishing cordial relations with strangers.’

A.C. Wilson – ‘Hard working but not clever. An excellent odd job officer, but will never be brilliant at anything.’

G.C. Colmore – ‘An unusually fine officer with a very strong personality. Has been all over the world and had every sort of adventure. Specially recommended for promotion.’

Unfinished: T.H.B. Hartford, Blundell, Hunter, Merchant, Brice, Hibbard and Park.72