Usborne’s Achievements and his Legacy

Neville Usborne made important contributions to the early development of four strands of naval aviation: the rigid airship, the SS Class nonrigid, the Coastal Class non-rigid and the airship-launched aeroplane. How did these progress in the years following his unfortunate demise?

British Rigid Airships

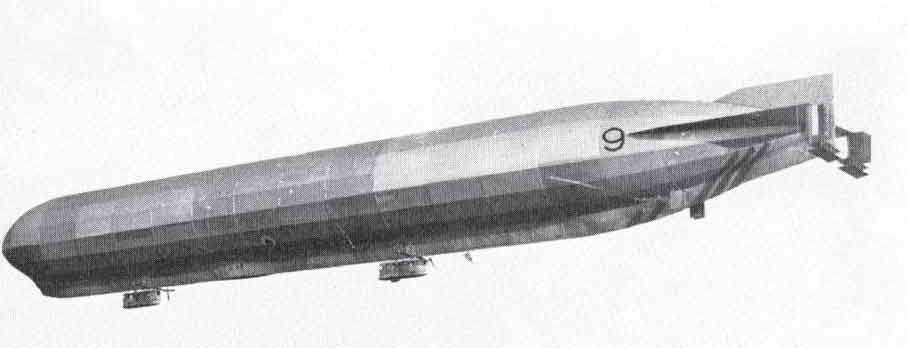

The Royal Navy’s rigid airship programme was suspended in 1911 after HMA No 1’s less than happy debut. HMA No 9r was originally ordered from Vickers in 1913, but, due to frequent changes of ministerial and naval policy, was not delivered from Barrow to the Rigid Trials Flight at Howden until April 1917, having become the first British rigid to fly on 16 November 1916, commanded by Wing Captain Masterman. Murray Sueter wrote; ‘When hostilities broke out No 9 Rigid was in her design stages. Then it was brought to the notice of the Admiralty that munitions were of greater importance than airships, so the work on No 9 was stopped, against the advice of the Director of the Admiralty Air Department (myself).’1 Her design was by then somewhat outmoded, being largely derived from a pre-war Zeppelin which had force-landed in France in 1913. She was slow and heavy, deliberately being strongly built to withstand ham-fisted handling by inexperienced crews. Her dimensions were: length 526 feet (160 metres), a diameter of 53 feet (16 metres) and a capacity of 846,000 cubic feet (23,942 cubic metres). The lack of a British rigid airship for reconnaissance at the Battle of Jutland in 1916 was regretted by the Director of the Naval Air Department:

‘I have always been convinced that if the naval airmen had been allowed to develop proper aerial reconnaissance of the North Sea, we could have done so much better on the naval side throughout the whole war period. The lack of British Zeppelins at Jutland was no fault of Lord Jellicoe.’2

HMA No 9r in 1916.

No 9r was used mostly for training and experimental work, but did carry out one operational patrol over the North Sea in July 1917. She was scrapped in June 1918 after a flying life of only 198 hours; 20 feet (6 metres) of her bow was salvaged by the commanding officer of Pulham Airship Station in Norfolk, for use as a bandstand and rose trellis.

The next British rigids were the four airships of the 23 Class, 23r, 24r, 25r and R26, which were delivered in 1917–18. In essence they were more advanced versions of 9r. For self-defence purposes, 23r was fitted experimentally with a two-pounder gun mounted on top of the envelope. They were used mostly for training, patrols and convoy work, though on 25 October 1918, R26, which was the best ship of the four, flew over London as part of the Lord Mayor’s Show, a unique appearance by an airship at this event. They were all deleted in 1919.

Airship R24 at East Fortune in 1917.

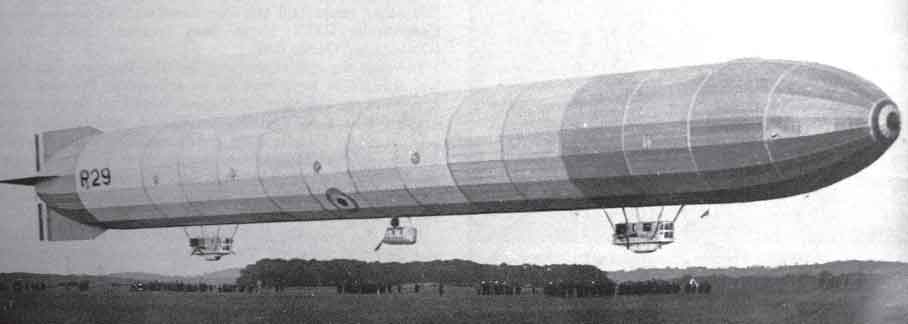

R29 at East Fortune in 1919.

The 23X Class, R27 and R29, followed; R27 was soon destroyed in an accidental fire in the hangar at Howden. R29 was more successful and was the only wartime rigid to see action, bombing a suspicious oil patch on 29 September 1918 off the coast near Sunderland, while on convoy duty. Signals made by Aldis lamp called in the destroyer escorts and subsequently the sinking of UB-115 was confirmed.

The next two airships, R31 and R32, were unusual in that their hull frameworks were based on the German Schütte-Lanz practice and were made of wood. During trials, R31 reached a speed of 70 mph (112 kph), but was scrapped after a career of only four hours and fifty-five minutes. R32 was seconded to the National Physical Laboratory for experimental work in manoeuvring and parachuting. One oddity of both ships was that their wooden frames flexed so much in flight that, ‘anyone standing in the control room doorway and watching a friend at the tail-end of the keel gangway would see him “disappear” and then “reappear” during turns.’3

Airship Service personnel had become members of the Royal Air Force on 1 April 1918, but ownership of the airships was not passed from the Admiralty to the Air Ministry until October 1919, by which time the number of rigid and non-rigid airships on charge had been greatly reduced.

Some idea of the comparative utility between the rigid and non-rigid RN airships during the war may be gained from the fact that – in total – the eight rigids flew 1500 hours of wartime patrols, whereas one non-rigid alone, the SSZ11, flew no less than 1610 hours. In one month in 1918 the SSZ11 was aloft for 259 hours – given the fact that the airships flew in daylight; this was more than half the actual hours available in the month. Another, SSZ20, flew 28,299 miles (45,278 kilometres) in 1918 in 1263 hours – a round-the-world journey at an average speed of 20 knots (23mph/37kph). One airship historian goes as far as to say:

‘Although they never received the same public acclaim that was so often bestowed upon the undeserving rigid airships, the SS Zero blimps were truly the unsung heroines of the war against the U-boats.’4

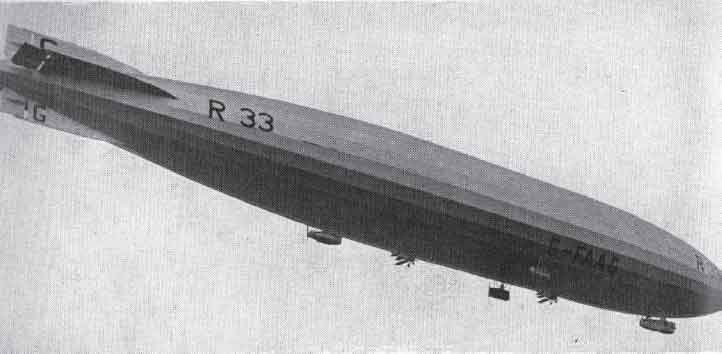

R33 was registered as a civilian airship G-FAAG in 1920. Note the pair of Gloster Grebe fighters suspended below the envelope.

Two of the most successful British airships were the R33 and her sister ship, R34, of 1919. Both were almost identical copies of the Zeppelin L33. Among the highlights of the R33’s career was the time that a brass band played on her top platform in flight and the early example ‘eye in the sky’ duty, when assistance was given to the police monitoring car traffic at the Epsom races in 1921. R33 continued to give valuable service until 1926. The R34 was built by the firm of William Beardmore, in Glasgow, and achieved considerable fame on 2–6 and 9–13 July 1919, when she made the first double crossing, including the first east-west crossing, of the Atlantic, from East Fortune in Scotland to Long Island, New York. The outward trip took 108 hours and 12 minutes, and the return trip to Pulham, assisted by the prevailing winds, took 75 hours and three minutes. This was only a few weeks after Alcock and Brown’s first west-east crossing from Newfoundland to Clifden, Co Galway, in their Vickers Vimy. The first east-to-west crossing by a heavier-than-air machine was not until 12–13 April 1928, in the Junkers W33 D1167, Bremen, flown from Baldonnel to Greenly Island, Labrador, by Captain Hermann Kohl, Baron von Hunefeld and Commandant James Fitzmaurice – the commanding officer of the Irish Air Corps. (In October 1910, Walter Wellman and his crew of five (plus dog) made an unsuccessful attempt to cross the North Atlantic from west-to-east in the small non-rigid airship America. Following engine problems and other difficulties, they were rescued by the SS Trent.)

Sadly, a minor accident, which was followed by severe weather damage while the R34 was moored out of doors on the ground, brought a premature end to this fine airship in January 1921.

R36 flew only 80 hours before being deleted and broken up for scrap in 1926.

The R36 was registered as a civil aircraft, G-FAAF, and used for passenger transport experiments. She was 673 feet (205 metres) in length, with a diameter of 79 feet (24 metres) and a capacity of 2,101,000 cubic feet (59,458 cubic metres). Her passenger cabin was luxuriously appointed with accommodation for fifty. On 27 June 1921, forty-nine MPs were taken for an hour’s flight, returning to the mooring mast at Cardington in Bedfordshire, which had recently been fitted with a lift. Her navigating officer was Flight Lieutenant Tom Elmhirst, who was one of Lord Fisher’s original young midshipmen drafted from the Grand Fleet in 1916 to fly the SS Class.

The first entirely post-war rigid was the ill-starred R38, which at the time of its construction was the largest airship in the world, being 699 feet long (213 metres), with a diameter of 86 feet (26 metres) and a capacity of 2,750,000 cubic feet (77,825 cubic metres). She was built by the Royal Airship Works at Cardington in response to an order from the US Navy and made her maiden flight on 23/24 June 1921, being re-registered in American markings as the ZR-2 in August. On 23 August she broke up in mid-air over the Humber; among the forty-four British and Americans on board was Air Commodore E.M. Maitland, CMG, DSO, AFC, whom it will be remembered, Usborne had rubbed up the wrong way slightly some seven years before. The R38 was badly designed and poorly stressed, so was unable to cope with the forces experienced during low-level manoeuvring. Much had been riding on the project; if it had been a success and had pleased the Americans, it was hoped that this would lead to an airship industry in Britain exporting its products around the world.

R38 leaving her shed at Cardington for the first time on 23 June 1921. (Ces Mowthorpe Collection)

Barnes Wallis, who had worked on airships for Vickers since 1913, designed the beautifully streamlined R80, which had considerably reduced drag compared to any of her predecessors; ‘There is little doubt that she would have proved the finest British airship.’5 Her maiden flight was on 19 July 1920, but before being scrapped in 1924, the R80 accumulated only seventy-five hours flying time:

‘This was a decision taken by a Labour Government to avoid a challenge from private enterprise, as R80 was costing less to maintain than the bigger ships designed by the official constructors’ team. Politically, the evidence was inconvenient.’6

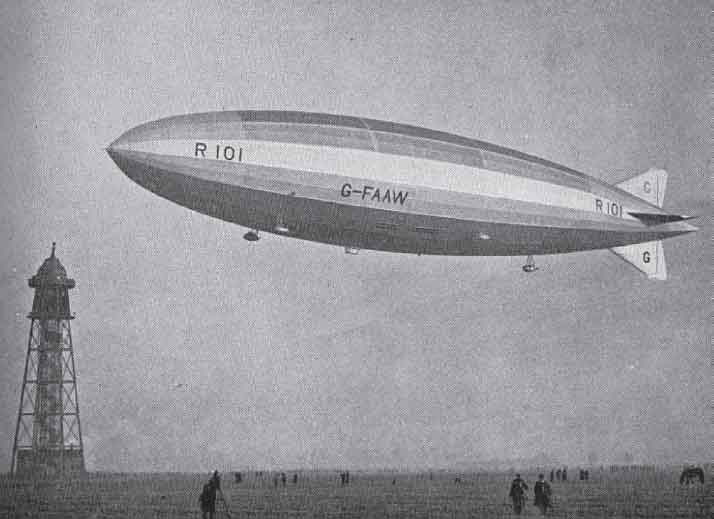

The final two British rigids could not have had more contrasting stories. The Cardington-built R101, G-FAAW, had a length of 777 feet (237 metres), a diameter of 131 feet (40 metres) and a capacity of 5,500,00 cubic feet (160,000 cubic metres), regaining for Britain the title of world’s largest aircraft. She was too heavy, lacking in engine power, and had leaking gasbags. The design was at the very edge of the technology then available. It was an experimental craft rushed – for reasons of political expediency – into a major and challenging flight before she was either ready or fully tested. The R101 was wrecked at Beauvais on her way to India on 5 October 1930 with a large loss of life, forty-eight of the fifty-four on board. The victims included the Secretary of State for Air, Lord Thomson, the Director of Civil Aviation, Sir Sefton Brancker and Major G.H. Scott, one of the most renowned airshipmen of the period.

The ‘government ship’, R101, approached the mooring mast at Cardington.

Air Vice-Marshal Sir W.S. Brancker, KCB, FRAeS, (1877–1930) a regular army officer, made his first flight in India in 1910 and from that time devoted the whole of his considerable talents to the furtherance of British aviation. During the First World War he held a succession of staff appointments in the RFC and then the RAF. In 1919 he left the service to become one of the great advocates of civil air transport, becoming Director of Civil Aviation in 1922. He was a very well known and popular figure of boundless energy and enthusiasm. His death in the R101 disaster of 5 October 1930 was a severe blow to the cause of aviation in the United Kingdom and beyond.

The R100, G-FAAV, was another creation of Barnes Wallis and was built at Howden, which was reactivated for the purpose in 1925–26. The chief calculator assisting Wallis was N.S. Norway, who later gained fame as the novelist Neville Shute, and whose autobiographical book, Slide Rule, includes the story of the two competing designs.

Also, seen here at Cardington, the ‘private’ contract, R100.

The R100 was 719 feet in length (219 metres), with a diameter of 133 feet (41 metres) and a capacity of 5,156,000 cubic feet (146,000 cubic metres). She is a strong contender with the R80 for the title of Britain’s finest airship; she was certainly the fastest, with a top speed in excess of 80mph (128kph). Her maiden flight was on 16 December 1929. In 1930, commanded by Squadron Leader R. Booth, she flew successfully to Canada and back. In the aftermath of the R101 disaster, there was a complete collapse of confidence in official circles in Britain as regards airships and, through no fault of its own, the R100 was grounded and scrapped, with less than £600 being raised by the sale of this. No British rigid has been built since then.

Squadron Leader R.S. Booth, AFC, (born 1895) was originally in the Royal Navy, transferring to the RNAS in 1915 to become an airship pilot, firstly of the SS and Coastal classes. He was appointed first officer of the rigid airship R24 in 1917; from 1924–26 he was the first officer and then captain of the R33, and in 1929–30 he captained R100, during which time the airship made its successful double crossing of the Atlantic.

Rigid Airships in the USA

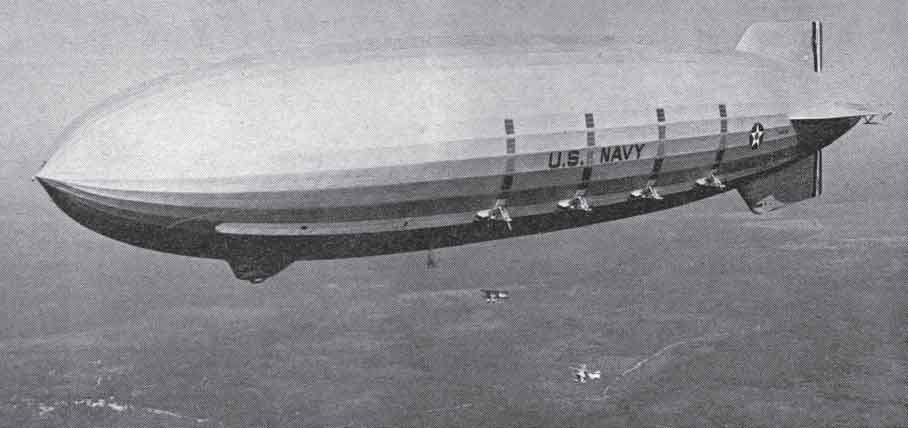

The American experience post-war was different in that it was the only country to have sufficient supplies of helium to make using this much safer gas a viable proposition. Their only large post-war airship using hydrogen was the semirigid Roma, purchased from Italy in 1921. It crashed at Langley Field, Virginia, in 1922 with the loss of thirty-four lives. The first of three rigid, helium-filled, airships was the USS Shenandoah, ZR-1, which was 680 feet (207 metres) long, 78 feet (24 metres) in diameter and had a capacity of 2,235,000 cubic feet (63,295 cubic metres). On 3 September 1925 she broke in two during a violent storm over Ohio; there were twenty-nine survivors from the crew of forty-three, who were saved by riding buoyant sections of the airship which fell to the ground like free balloons. On 4 April 1933, the USS Akron, ZRS-4, was forced down into the sea off the coast of New Jersey with the loss of seventy-four crew members out of seventy-seven, the world’s worst airship accident. Her sister ship, the USS Macon, ZRS-5, encountered a storm off Point Sur, California, on 12 February 1935 and suffered a similar fate, fortunately with a very much lower loss of life. These last two airships were among the largest ever built, being 785 feet (239 metres) in length, with a diameter of 132 feet (40 metres) and a capacity of 6,497,960 cubic feet (184,000 cubic metres). It is an odd fact that all three succumbed to adverse weather conditions. The USA joined Britain in abandoning the rigid airship. This left the field to Germany.

USS Shenandoah.

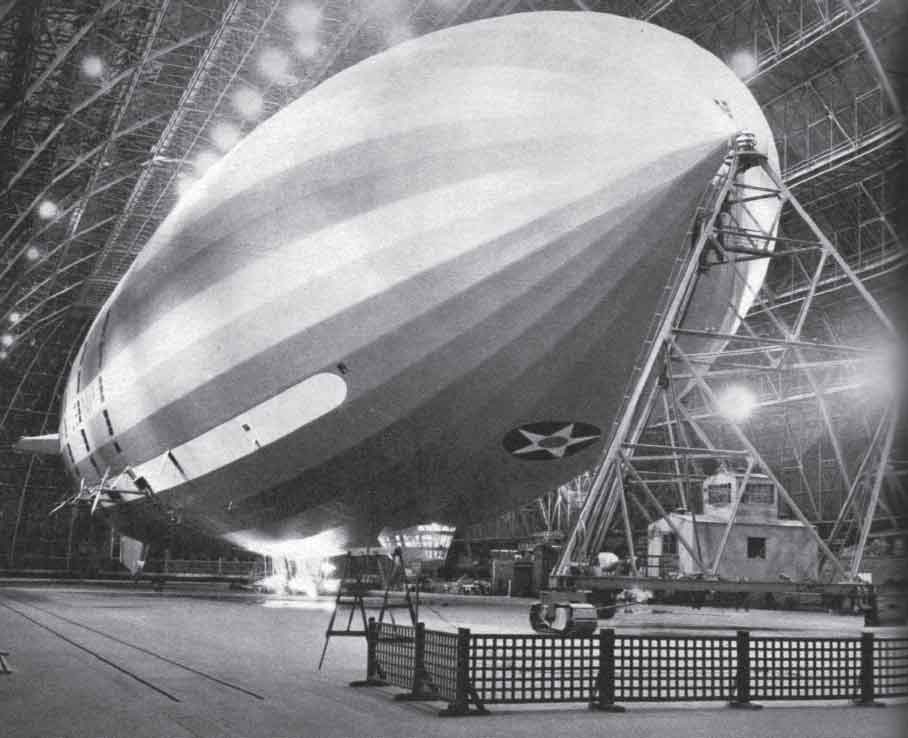

The USS Akron moored inside the Goodyear air dock.

Zeppelins

In the aftermath of the First World War, Germany had been greatly restricted by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles with regard to the further development of airships.

Article 198

The armed forces of Germany must not include any military or naval air forces. No dirigible shall be kept.

Article 202

On the coming into force of the present treaty, all military and naval aeronautical material must be delivered to the governments of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers. In particular, this material will include all items under the following heads which are, or have been, in use, or were designed for warlike purposes:

Dirigibles able to take to the air, being manufactured, repaired or assembled.

Plant for the manufacture of hydrogen.

Dirigible sheds and shelters of every kind for aircraft.

Pending their delivery, dirigibles will, at the expense of Germany, be maintained inflated with hydrogen; the plant for the manufacture of hydrogen, as well as the sheds for dirigibles, may, at the discretion of the said powers, be left to Germany until the time when the dirigibles are handed over.

A brief resumption of commercial services in 1919, during which 103 flights were made and 2450 passengers carried, terminated when the Zeppelins LZ121 Nordstern and LZ120 Bodensee had to be handed over to France and Italy respectively as reparations. The Zeppelin works was saved by the order of an airship from the USA; this was the LZ126/ZR-3 USS Los Angeles, which was completed in 1924. While the Zeppelin workforce was happy, the Berlin Morning Post was not, commenting unfavourably on a ship, ‘built in Germany by German workers and engineers, paid for with German money, but which belongs to America.’7 Her delivery flight on 13–15 October 1924, commanded by Dr Hugo Eckener, was the third airship crossing of the Atlantic, after R34’s double run in 1919. In US service the hydrogen originally used was replaced with helium. She was the most successful rigid airship ever operated by the US Navy and had an unblemished eight year flying career of nearly 5000 hours.

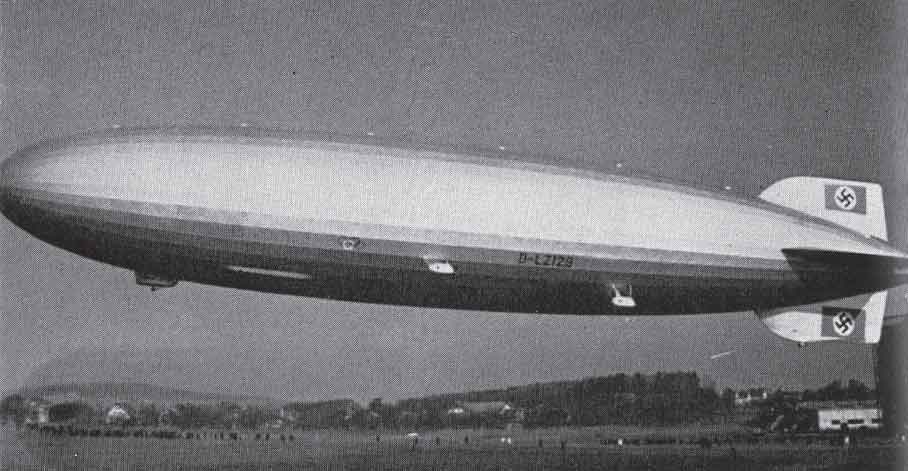

The greatest rigid airship of all time first took to the skies on 18 September 1928. This was LZ127, the Graf Zeppelin. She was 775 feet long (236 metres), 100 feet in diameter (30 metres) and with a capacity of 3,700,000 cubic feet (104,784 cubic metres). Her five Maybach engines of 550 hp (410kW) each, gave her a top speed of 80mph (129kph) and a cruising speed of 68mph (109kph). For the next decade she was one of the most famous aircraft in the world, regularly making the headlines and newsreels with spectaculars, including a round-the-world flight in August 1929, with a research trip to the Arctic in 1931, and multiple crossings of the North and South Atlantic. The Graf Zeppelin’s engines ran on ‘Blau Gas’, which had several advantages over liquid fuels such as petrol. It was non-explosive, and because it was only slightly heavier than air, burning it and replacing its volume with air did not lighten the airship – eliminating the need to adjust buoyancy or ballast in flight.8 She was followed by the largest flying machine ever built, the LZ129, Hindenburg, which measured 800 feet (245 metres) in length, had a diameter of 135 feet (41 metres) and a capacity of 7,000,000 cubic feet (198,240 cubic metres). The Hindenburg was destroyed by fire as she arrived at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on her first commercial flight to the USA on 6 May 1937. A sister ship, the LZ130, Graf Zeppelin II, flew briefly in 1939 and carried out some electronic intelligence gathering missions probing British radar defences, but in 1940, both LZ127 and LZ130 were broken up for scrap. So ended the rigid airship era which had lasted for some forty years.

LZ129 Hindenburg.

Proof of concept with regard to intercontinental flights had been established by the exploits of LZ104, the Afrikaschiff, in November 1917. She took off from Yambol in Bulgaria to fly to German East Africa with supplies to relieve the hard-pressed force of General von Lettow-Vorbeck. While the airship was enroute, erroneous reports arrived that von Lettow-Vorbeck had been defeated and it was not until the Afrikaschiff had overflown Khartoum that a recall message was received on board. She returned to base some four days after her departure, having flown a record breaking ninetyfive hours and covering 4200 miles (6800 kilometres) in challenging and changing climatic conditions.

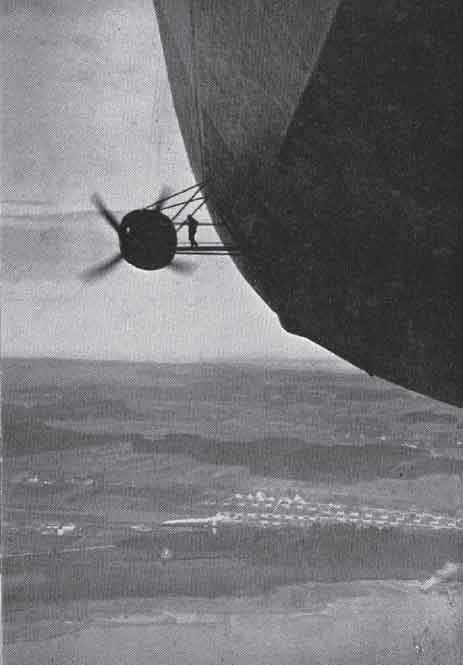

A mechanic crosses to the Hindenburg’s port forward engine gondola.

It was in the end a technological cul-de-sac, rigid airships were too slow and unwieldy to compete with fixed-wing aircraft, and, along with the flying-boat, are now icons of a time when air travel had glamour and style. They were not big enough to make their speed advantage over surface shipping commercially viable. The construction techniques and materials available at the time could not make craft (apart from a few notable exceptions) which were able to survive stormy weather. (It is of interest that Lord Rayleigh was of the opinion that there was nothing more difficult than calculating the stresses, particularly the torsional stresses of a rigid.)9 The contemporary naval fixed-wing airman, Richard Bell Davies, had some interesting comments to make with regard to airships and safety:

‘I have never been a great believer in the future of airships, but I think one of the reasons that they failed to do better than they did was due to the difficulty of giving long enough training to their captains. The master of a merchant ship has usually spent ten years or more in a subordinate position before he is given command. He has seen the ship berthed literally hundreds of times and has seen her handled in all sorts of weather. I suppose in the whole world there has only been one man who had experience with airships comparable to the ship experience of the average British Master Mariner. This was Dr Eckener when he commanded the Graf Zeppelin. She had no accidents and made trips all round the world.’10

The Graf Zeppelin lands at Los Angeles, note the Goodyear blimp in the background.

There is much food for thought in this statement, as there also is in remarks made by Murray Sueter:

‘The tide tables, laws of storms, etc, as applying to surface vessels, have been built up by years and years of patient labour by experts all over the world. Surely, then, it is not unreasonable to suppose that the same study of the conditions in the lower strata of the atmosphere in the England, Egypt, India, Australia, South Africa and Canadian air routes will have to be considered for the use of airmen navigating all types of aircraft, so that they can be guided in the same way as the seaman is in the normal conditions expected. The meteorological staff are not fools; they and the airship staff realize the importance of wind currents, both permanent and otherwise, and that is why they are analysing the lower strata of the atmosphere in the area of the England-Egypt-India route for every day of the year, in order to discover what are the normal conditions to be expected.’11

It remains a question, could a niche still be found for a rigid airship equipped with advanced avionics and engines, built from strong but light composite materials? Could it be used to deliver heavy plant and machinery to remote and inaccessible areas, or as an aerial cruise liner?

In all, 147 Submarine-Scout type airships were constructed, twenty-nine with the BE2c fuselage, twenty-six Maurice Farman types, ten with an Armstrong-Whitworth car, six SS-Pushers (which had rubberized fabric petrol tanks, which were not a success and were soon replaced by aluminium ones) and seventy-six improved model SS Zeros. The SSZ was built to the design of three RNAS officers, Commander A.D. Cunningham, Lieutenant F.M. Rope and Warrant Officer Righton, at RNAS Capel, near Folkestone. Work started on building the prototype in June 1916. The car was specifically designed to be streamlined in shape and was constructed almost like a boat, with a keel and ribs of wood with curved longitudinal members. The whole frame was braced with piano wire and then floored from end to end. It was enclosed with eight-ply wood covered with aluminium. The crew of three consisted of the wireless telegraphist/observer/gunner in the front, with the pilot in the middle and the engineer in his own compartment to the rear. A machine gun could be mounted either to port or starboard, operated from the front seat, and two 110lb bombs could be carried. The car, as well as being boat-shaped, was watertight, so the airship could land on calm water. The engine was a great improvement. It is said that the engineering officer at Kingsnorth, Lieutenant T.R. Cave-Browne-Cave, had complained time and again about the adapted aero engines used in the SS Class, which because they were not designed for use in airships, were unsuitable for slow, sustained flight and were always giving trouble. His commanding officer, tiring of this, ordered him to go and do something about it. So, taking him at his word, Cave-Browne-Cave took the train to Derby and requested a meeting with Henry Royce. After only a few hours of discussion an engine specification was agreed. This became the 75 hp Rolls-Royce Hawk six-cylinder, vertical inline, water-cooled engine driving a four-bladed pusher propeller; 200 of these were manufactured under licence by Brazil Straker of Bristol, which was the only company entrusted by Henry Royce to build complete engines. It was a superb creation and was test run for the first time at the end of 1915. The words of an airship pilot tell it all; ‘The sweetest engine ever run – it only stops when switched off or out of petrol.’12 It gave the airship a top speed of 53mph and a rate of climb of 1200 feet per minute. Slung on either side of the gasbag were two petrol tanks made from aluminium. The gasbag had a capacity of 70,000 cubic feet. It was of the same length as the SS Class gasbag, but was of a slightly greater diameter. The nose of the gasbag was reinforced by radially positioned canes to prevent it buckling at speed. As with the SS Class it was attached to the car with cables secured to the envelope by kidney-shaped Eta adhesive patches, which were also sown on, so spreading the load evenly. The SSZs, or Zeros as they were known, which first flew in September 1916, were more stable in flight than the SS Class and had much greater endurance. They were able to fly in weather conditions that would have prevented the earlier type from operating. Its unit cost was about £5000. It rapidly gained the approval of its pilots:

‘The SSZs were dreams come true. I fell for them almost at once. At last we had a trouble-free engine and our engineers were able to get some sleep at nights.’13

An SSZ Class airship, looking over the pilot’s head to the engineer’s station at the rear of the car. (via Tom Jamison)

The larger and longer range Coastal Class were the workhorses of the airship service, seeing more action than any other type; in all thirty-five of these were produced, flying from bases in Kent, Cornwall, Sussex, Norfolk, Wales and Scotland. The most famous of these was C9, which entered service at Mullion in Cornwall on 1 July 1915 and flew a record 2500 hours (averaging three hours six minutes per day flying time) and more than 68,000 miles (108,800 kilometres) before being retired from active service on 1 October 1918. She attacked several U-boats successfully. In 1917 the indefatigable Wing Captain Maitland made an experimental parachute jump from C17. It is believed that two, and possibly three, of this class were lost due to enemy action, two in duels with German seaplane fighters and one in an action with a U-boat, with the result that the order was given that their top gun, mounted on the envelope, should be manned at all times. It is thought that the two which were shot down by aircraft had strayed too close to enemy-occupied territory. They were the only airships destroyed by hostile fire.

The Coastal Class was followed by the improved C Star Class, ten of which were constructed. It was an interim type produced at short notice by the team at Kingsnorth because of problems with the development of the North Sea Class. They were 207 feet in length (63 metres), 217 feet (66 metres) from C*4 onwards, with a maximum diameter of 47 feet (14 metres) and a capacity of 210,000 cubic feet (5943 cubic metres). The streamlined, tri-lobe envelope and the 220 hp (163kW) Renault engine aft, with a 110 hp (81kW) Berliet forward, allowed a faster top speed of 57mph (91kph). The car was clad in plywood rather than canvas, with portholes of Triplex glass to each side and in the floor. Provision was also made for static line parachutes for the crew in case of emergency. The longest flight made by a C* was one of thirty-four and a half hours, made by C*4 in May 1918.

Coastal Star Class airship C*7, note C*5 in the background. (J.M. Bruce; G.S. Leslie Collection)

A North Sea Class airship over East Fortune in 1917. (Jack McCleery)

North Sea Class airship NS4.

When the North Sea Class had recovered from its teething problems under the care of the Kingsnorth design team, it quickly proved to be the most efficient of the British blimps. The class was once more based on the Astra-Torres tri-lobe pattern, but was larger again, with a length of 260 feet (79 metres), maximum diameter of 57 feet (17 metres) and a capacity of 360,000 cubic feet (10,188 cubic metres). Power came from a pair of 250 hp (185kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle engines, with a design maximum speed of 55mph (88kph), though on occasions modified craft reached 70mph (112kph). Fifteen of this class were delivered before the Armistice, when production was cut short. The car, which contained control, navigation and wireless rooms, accommodation and sleeping space, was completely enclosed and was made from steel tubes clad in Duralumin and fabric. There was also a separate engine car connected by a walkway. The crew of ten were split into two watches, so patrols of several days in duration could be made. There were also cooking facilities on a hot-plate fitted to an engine exhaust. Up to five machine guns could be fitted and six 230lb (104kg) bombs could be carried. When the German High Seas Fleet surrendered and sailed into British waters in November 1918, NS-7 and NS-8, which were based at East Fortune on the Firth of Forth, escorted them in, positioned to starboard and in the centre of the fleet respectively. A world endurance record of 100 hours and 50 minutes was set by NS-11 in February 1919. In March, NS-11 and NS-12 made the first airship flights to Norway.

Three large non-rigids of the Parseval type were built by Vickers at Barrow and assembled at the airship station at Howden in Yorkshire, and also gave useful service, as did the thirteen SS Twin Class, of which 115 were planned and which were about half the envelope size and two thirds the length of the Coastal Class.

That their utility was valued throughout the war may be seen from two official documents, the first a memorandum from Captain F.B. Scarlett, DAD, and dated 26 March 1918:

‘The following shows the number and types of different airships in commission:

‘SS 9; SS Pusher 3; SS Zero 31; SS Twin 1; Coastal 9; Coastal Star 2; North Sea 3; Parseval 3 and Rigid 5.

Notes

‘The SS Type was the first small airship commissioned, motive power supplied by one 75 hp engine. This type is now used for training.

‘The SSP Type is a slight improvement on the former.

‘The SSZ Type, which is in extensive use on most of the airship stations, is a decided improvement on the two foregoing types, and has proved extremely useful for anti-submarine patrol.

‘The SST Type is similar to the SSZ, with the exception that it has two engines and is known as the SS Twin. The first unit of this type has just undergone its trials, which were extremely promising, the extra engine giving this ship a greater speed and making it much more reliable in case of engine failure.

‘The C Type ship, known as the Coastal Patrol, will very probably be superseded by the SS Twin, although it has been extremely useful for patrol work.

‘The C Star Type is an improvement on the C and has not been commissioned very long.

‘The NS Type ship, known as the North Sea type, was designed for the purpose of doing extensive patrols in the North Sea, but up to the present has not given very good results.

‘The P ship is the original German Parseval type.

‘The R type ship is known as the Rigid and has been constructed on the lines of the German Zeppelins. These ships should still be considered as experimental.’14

The second is a planning paper written for the Board of the Admiralty, setting out airship requirements in the event that the war continued into 1919:

‘In pursuance of Minute 354, the committee have reviewed the situation with regard to Rigid and Non-Rigid Airships, and they have agreed upon the following report and recommendations:

Non-rigid Airships

‘In connection with the approved programme for completing 115 SS Twin-Type airships by June 1919, the committee found that the experiments with the Sunbeam Dyak engine, referred to in their previous report, have been successful, and that the Air Ministry are arranging to have this class of engine built for the Admiralty by the firm of Messrs Sunbeam. The delivery of this engine will commence in December, some months earlier than was anticipated, but on the other hand the dates for delivery of Rolls-Royce Hawk engines indicated in the previous report of the committee have been somewhat deferred.

‘The approved programme of SST airships should therefore ensure the completion, by the end of June 1919, of 117 airships (including two experimental) which, with fifty-eight SSZ in commission and one in reserve, and thirteen SS and SSP airships (that is 189 in all), and allowing for a deletion of six for obsolescence, but making no allowance for casualties, would give us a stock of 183 airships from 1 July next.

Rigid Airships

‘The committee found that the dates for the completion of rigid airships as indicated in their previous report had not been, and, cannot be realised, owing to difficulties in regard to construction and trials, shortage of labour, and in some cases alteration of design. By Board Minute 354, the number of rigid airships to be maintained in commission has been reduced to eleven, so that no further housing accommodation for rigid airships is required beyond that at present existing and in course of construction at Howden in Yorkshire and Killeagh in Co Cork, Ireland.

Generally

‘The committee recommend that in future the situation with regard to rigid and non-rigid airships should be reviewed by them at intervals of three months, when account will be taken of any further orders rendered necessary by casualties which have occurred during the previous quarter.

‘The report of the committee may be summarised as follows:

1. ‘That the approved programme of SST airships should ensure the completion, by the end of June 1919, of 117 Airships (including two experimental) which, with fifty-eight SSZ in commission and one in reserve (obtainable by utilising large spares already in stock), and thirteen SS and SSP airships (that is, 189 in all), and allowing for a deletion of six for obsolescence, but making no allowance for casualties, would give us a stock of 183 Airships on 1 July 1919.

2. That no further housing accommodation will, prior to 1 October 1919, be required either for rigid or non-rigid airships beyond that already existing or approved.

Recommendations

1. ‘That a further forty-eight SS Twin airships be now ordered for delivery in July, August and September 1919, in order to maintain continuity of production and to allow for casualties.

2. ‘That no further large spare parts be ordered for SSZ Type, and that this type of vessel be allowed to die out as existing large spares are used up.

3. ‘That the SS and SSP type be maintained as necessary by minor repairs only, and that they be allowed to die out when it becomes necessary to use large spares.

4. ‘That non-rigid airships lost, prior to 1 October 1918, be made good from stock, but that subsequent to that date, ships completely lost be struck off the establishment, and ships partially destroyed, of which any material part remains, be replaced out of spares.

5. ‘That the situation with regard to both rigid and non-rigid airships be reviewed by the committee at intervals of three months.’15

No other contemporary aircraft could have performed the jobs airships undertook. None could match the airships’ endurance or slow speed capability. They could stay close to the convoys and their escorts for extended periods; either scouting ahead for submarines or mines, or standing off to windward, ready to swoop down rapidly to investigate a possible threat. Indeed, it could be said that the airships’ potential was, even by the later stages of the war, not fully appreciated. Those operating with the Grand Fleet were sent ahead on scouting missions, but were forbidden by the C-in-C, Admiral Beatty, to go beyond visual range of the leading vessels, thus not breaking radio silence, but greatly limiting their range of vision over the horizon.

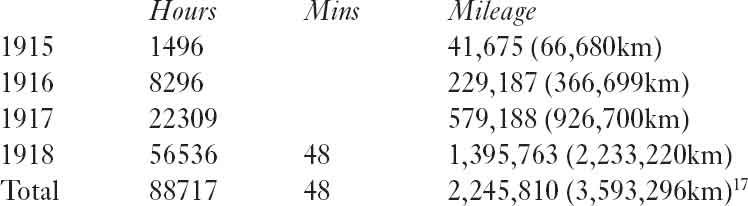

Another limitation imposed on the use of airships was described by Rear Admiral Murray Sueter, when he revealed in a book published after the war that he had proposed to the Admiralty in 1915 a scheme for the extensive aerial surveillance of shipping to be carried out by airship in the Mediterranean. This was turned down on the grounds of cost and in Sueter’s opinion prevented the solution to what became a very costly destruction of shipping in that theatre.16 He made this summary of the RN Airship Service’s contribution in World War One, which had grown in size to 580 officers and 6534 men at eighteen airship stations:

On 1 November 1918 there were 103 airships in commission, five rigids, one Parseval, six North Sea, ten Coastal Star, four Coastal, twelve SST, fifty-three SSZ, three SSP and nine SS.18 It should be noted that in the course of this valuable service only fifty-four airshipmen lost their lives from all causes. Sixteen airships in total were lost, mostly through accident or mishap. The most intense part of the campaign was from June 1917 to October 1918. During these sixteen months, on average, fifty-six airships were on duty every day and a total of 9059 patrols were carried out, the average duration of which was six hours and seventeen minutes. A total of 59,703 hours were flown, including 2210 escorts of shipping; 134 mines were sighted, of which seventy-three were destroyed; forty-nine U-boats were spotted, twenty-one of these were attacked with the help of surface craft and six by airships on their own. Their deterrence value was immense – during the entire war there was only one instance of a ship being escorted by an airship being sunk. This may be placed in context by considering the fact that of the 12,618,283 tons of merchant shipping lost in the First World War, 11,135,460 tons were sunk by U-boats – eighty-eight per cent of the total. During the final fifteen months of the war, SS type airships carried out over 10,000 patrols, flying nearly one and a half million miles in more than 50,000 hours. The submarines were kept below the waves, where they used up valuable battery power and were restricted to a speed of only eight or nine knots. A brief log entry from a captured U-boat speaks volumes; ‘Sighted airship – submerged.’ An analysis written in a respected, post-war, monthly magazine noted:

‘The Germans stated that what they disliked most in the Irish Sea area were the airships that were always passing over them. They did not fear the bombs these craft carried, but they did dislike having their own position continually reported to the surface patrols, who, as a result, gave them little rest. There is no doubt that the morale of submarine personnel is much affected by continual nerve strain.’19

The Royal Navy’s non-rigid airships did not win the battle against the U-boats on their own, but they made a highly important and unique contribution, without which the struggle would have been much more difficult. It was; ‘An instrument of knowledge rather than power.’20

There is a remarkable consensus of opinion between contemporary commentators, politicians and airshipmen, as well as historians in later years. There is not a single dissenting voice, all agree on the utility, effectiveness and value for money of the naval non-rigid airships. Within a few months of the cessation of hostilities most of the non-rigids were withdrawn from service, as the RAF contracted hugely, and financial pressures bit into the budget. They were used extensively in mine-clearance operations, but by the summer of 1919 most had been deflated for the final time. The last non-rigid to serve with the RAF was NS-7, which was based at Howden in 1920, training the crew of R38. It flew for the last time on 25 October 1921.

It was to the airships’ advantage that they operated in an environment without predators or effective countermeasures; there were no aircraft carriers to bring fighter aircraft within range and the U-boats were not equipped with antiaircraft armament, nor did they really wish to remain on the surface and fight it out. Experimental use was made of SSZ1 in towing trials with the Lord Clive Class monitor, HMS Sir John Moore, off Dunkirk in 1916. The plan was to see if the airship could be used to spot for the monitor’s 12 inch (304mm) guns as it bombarded German positions. It was quickly realised that the slow speed of the airship made her employment that close to the enemy coast impracticable. Another airship, SS-40, served briefly on the Western Front from Boubers-sur-Canche, near Arras, in the summer of 1916; she had a larger envelope, which was painted black. On a trial flight from Polegate it was noted by the War Office acceptance team; ‘The ship became invisible as soon as she took off; seemed to go round in a circle and fade away. Never saw her again till she landed. Very good show!’ However, in France, the results were disappointing as the Black Ship, or Bertha the Black Blimp, as she was known, could only operate safely at night, when there was little that could be seen, so the experiment was abandoned after only two flights. Or was this merely a cover story? Interestingly, the memoirs of one airship pilot, relating to his time at Kingsnorth, refer to SS-40:

‘Disappearing from time to time, she was used for night work over France, dropping men behind the lines.’21

SS-40: The Black Ship.

This is corroborated to an extent in a memoir by Air Marshal Sir Victor Goddard in preparation for a talk on the BBC in 1955, which was never broadcast:

‘Many’s the time that the Black Ship sailed over the lines at night through that long summer and autumn of rumbling, bloody battle. But never once with an agent to drop. Spies are brave men, but they didn’t fancy our airship as a mode of travel. Instead, Flight Sub-Lieutenant Billy Chambers and Captain C.R. Robbins made night reconnaissance from which all too little could be learned about the enemy’s movements. Coming back from a clandestine operation, the crew of the Black Ship would sing a bawdy song as they approached their hangar at treetop height, with the engine throttled back. The singing was to alert the ground crew and also to discourage any Tommies below from taking pot shots at the almost silent shape. Chambers was mentioned in dispatches in General Haig’s report on the Battle of the Somme.’22

Despite this hint of cloak and dagger work it can be said that the technology was only able to survive in the context of the conditions pertaining between 1914 and 1918, or was it?

To war with the US Navy (Twice)

A small number of blimps were used for coastal patrol duties by the US Navy in 1917–18. An assortment of small non-rigids of various sizes was maintained by the US Army, and then exclusively the navy, between the wars. The major operator in the inter-war period was the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation of Akron, Ohio, which built the following small, helium-filled, non-rigid airships, including Pony (1919–23), Pilgrim (1925), and the extended fleet of the later 1920s and early 1930s: Puritan, Volunteer, Mayflower, Vigilant, Defender, Reliance, Resolute, Rainbow, Enterprise, Ranger and Columbia. A typical example would have been 140 feet (42.67 metres) in length, with a diameter of 40 feet (12.19 metres), a volume of 112,000 cubic feet (3169 cubic metres), driven by two 110 hp (81.4kW) engines, giving a speed of 60mph (96kph) and the ability to carry six passengers. By 1942 they had made 151,810 flights, 92,000 flying hours, with a total distance of more than 4,000,000 miles (6,437,000 kilometres) in every state east of the Mississippi, but also to Texas, California, Cuba, Canada and Mexico, carrying 400,000 passengers in complete safety. Their versatility was immense: delivering mail and newspapers, taking aloft press reporters, newsreel cameramen and radio announcers to report on sports and other events, facilitating wildlife, civil engineering and traffic studies, disaster and emergency relief, rescues from the Everglades and at sea, and pleasure flights, to list just some of the roles for which they were used.23 The pilots, crew and ground staff gained vast experience operating their craft in all weathers and became very confident with the ability of their ships to fly in all but the most adverse of conditions. Perhaps the worst hazards were the attentions of trigger-happy and thoughtless hunters, which at least proved that the blimps could sustain bullet damage and fly on. Many of the Goodyear pilots were commissioned as reserve officers in the USN, giving a nucleus of experience from which the naval airship service could expand. As for the Goodyear blimps, they had naval markings applied and were pressed into service for training duties.

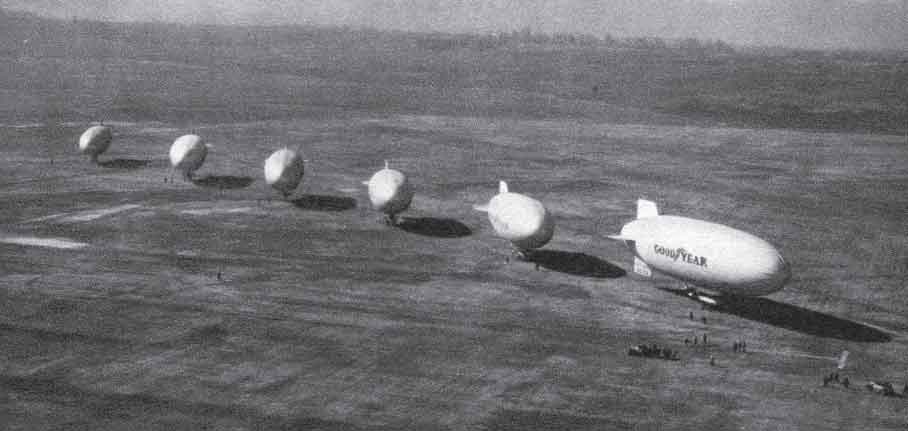

A Goodyear blimp lands at the Century of Progress Exposition held in Chicago in 1933–34.

The Goodyear fleet at Akron.

USN blimp G-1.

USN blimp K-3.

In 1941 the US Navy had a handful of blimps. After the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, the Navy asked the US Congress for authorization to purchase many more. By June 1942 the construction of 200 helium-filled airships had been authorized. During the next three years Goodyear built a total of 168. At its production peak, the company was turning out eleven airships monthly. The United States was the only power to use airships during World War II, and the airships played valuable roles. The USN employed them for minesweeping, search and rescue, photographic reconnaissance, scouting, escorting convoys, and anti-submarine patrols.

In the bitter and crucial Battle of the Atlantic in 1942, nearly 500 merchant ships were sunk on the eastern seaboard of the USA alone. Remarkably, part of the answer was found to be the establishment of an eventual total of five Fleet Airship Wings, with a strength of more than 100 blimps in fifteen squadrons stationed not only on either side of the continental USA, but also in Jamaica, Brazil, Trinidad, French Morocco and Gibraltar; patrolling an area of over three million square miles (7.8 million square kilometres) over the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and the Mediterranean Sea between 1942 and 1945. They were very reliable, being available for duty eighty-seven per cent of the time; 35,600 operational flights were made in the Atlantic and 20,300 in the Pacific, for a total of 5,550,000 hours in the air escorting 89,000 ships loaded with troops, equipment and supplies. No ship escorted by a blimp was ever sunk and only one of the airships was lost to enemy action – K-74, which fought a duel with a U-boat.24

After 1945 the USN carried on with using blimps in anti-submarine warfare, search and rescue (SAR) and early warning roles. Some were equipped with huge airborne radar sets for early warning of bomber attacks against the USA. Two of the largest airships were the ZPG-2 at 324 feet (99 metres) in length and a capacity of 875,000 cubic feet (24,777 cubic metres), and the ZPG-3 at 403 feet (121 metres) long and a capacity of 1,516,000 cubic feet (43,000 cubic metres), the latter being the largest blimp ever built. An airship of this type could stay aloft without refuelling for more than 200 hours. On 31 August 1962, the navy ended its use of blimps. In the 1980s the USN examined once more the possibility of reviving airships, but Congress terminated funding for the project in 1989.

[Author’s note: It is of interest to note that Betty Usborne’s son, John Godley, later Lord Kilbracken, took part in successful anti-submarine operations, based in Ireland during the Second World War, which used what was regarded as outmoded technology. Maydown, in Co Londonderry, was the headquarters for MAC (Merchant Aircraft Carrier) ship operations. This type of aircraft carrier proved to be a highly effective countermeasure to the U-boat offensive from mid-1943 onwards. These were standard grain carriers or oil tankers fitted with an elementary flight deck from which a flight of three or four Swordfish biplanes was operated. Each flight of Swordfish flew from Maydown to join the carrier off the Irish coast, and returned to base after the journey across the Atlantic and back. It is a remarkable fact that, of the 217 convoys in which a MAC ship sailed, between May 1943 and the end of the war, only one was attacked successfully by a U-boat. Three parent units for the Swordfish were based at Maydown, 836 and 860 NAS, for operational deployment, and 744 NAS for training; 836 was the largest operational squadron in the FAA. Together, the Maydown squadrons provided over ninety Swordfish for some nineteen MAC ships. The last FAA squadron to relinquish the famous Swordfish was 836 at Maydown in July 1945. Northern Ireland remained a very important location for air anti-submarine activity for the next thirty years, with the Joint Air Submarine School (JASS) at Londonderry until 1969, the Air Anti-Submarine School at RNAS Eglinton (now City of Derry Airport) which closed in 1959 and RAF Coastal Command Shackletons flying from Aldergrove until 1959 and Ballykelly until 1971. The long tradition of maritime surveillance in Ireland is now maintained by the Irish Air Corps from its base at Baldonnel on the outskirts of Dublin.]

The British Army Considers an Airship

Remarkably, a plan conceived in the mid-1990s renewed the British Army’s connection with lighter-than-air aviation after a gap of some eighty years – in the bulbous shape of ZH762, a Westinghouse Skyship 500 built by Airship Industries of Cardington. It was 170 feet (52 metres) long, 46 feet (14 metres) in diameter and had a capacity of 182,000 cubic feet (5150 cubic metres). The helium-filled envelope was laminated, lined with gas-retention film and sprayed externally with a polyurethane coating. The car was attached to the envelope and was made from reinforced plastic; it was powered by two Porsche 930 engines of 205 hp (151kW) each, and, as with previous blimps, they were fitted with swivelling propellers and its ballonets were fed from the slipstream. Skyships have been used for tourist flights, fishery patrols, aerial photography and a range of other activities. This airship was flown by Army Air Corps pilots in the course of an extensive trials programme, which included a visit to 5 Regiment AAC at RAF Aldergrove. It had the advantages of being able to lift a considerable quantity of mission-related equipment and of being able to remain in the air for protracted periods of time. Against these benefits had to be set the undeniable facts that it was slow, not being capable of more than 30–40 knots (34–45mph/55–74kph) cruising speed and that it was not well-suited to windy or icy weather conditions. Useful experience was gained, but the AAC decided in the end not to establish a new airship unit.

Westinghouse Skyship 500 ZH762 at RAF Aldergrove in 1995. (5 Regiment AAC)

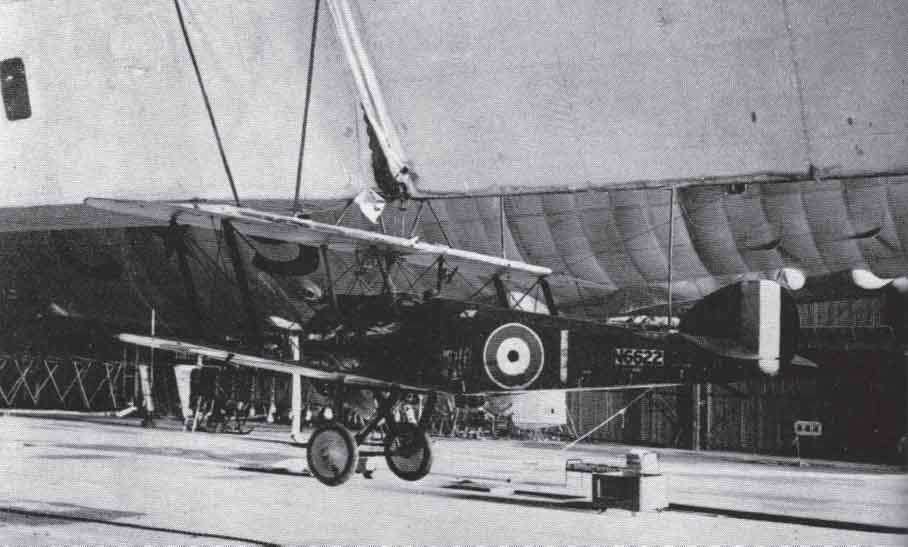

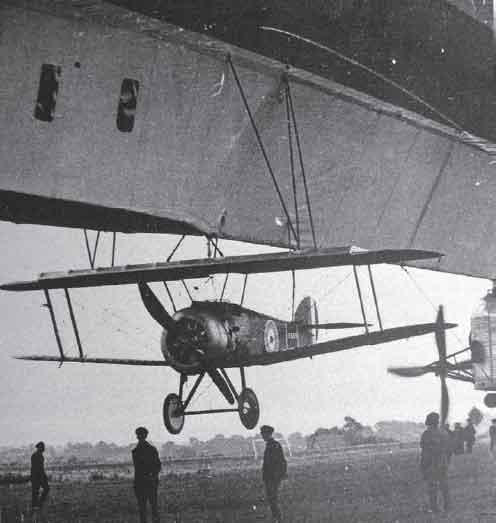

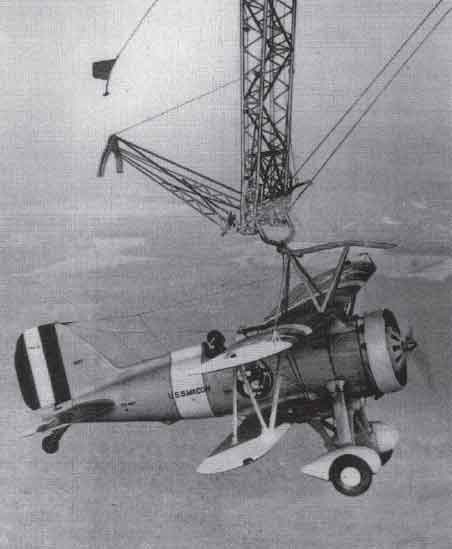

The last scheme hatched by Neville Usborne was the one that would result in his tragic, early demise – the idea of an aeroplane carried aloft by an airship. Though further development of the AP-1 was terminated, aircraft were indeed to be borne aloft by airships. Trials were carried out by both the British and the Germans in 1918. On 26 January, an Albatros D.III single-seat fighter, serial number 3066, was fixed under the airship L35 (Zeppelin LZ 80) of the Imperial German Navy to test the idea of protecting airships by attaching a fighter which could fly off to defend the mother ship if it was attacked. The pilot was in the cockpit throughout and could not be transferred in flight. The trial was a success in that the Albatros, which had kept its engine running for the duration of the flight as there was no way of manually restarting it once the Zeppelin was airborne, was released from a height of some 5000 feet (1500 metres) and flew away safely. Then, on 6 November, Sopwith 2F.1 (or ‘Ships Camel’ as it was commonly known) N6814, flown by Lieutenant R.E. Keys, DFC, of No 212 Squadron RAF, was dropped from the British airship R23 and landed at Pulham in Norfolk. R33 was the next British rigid to be used for experiments of this nature, releasing a pilotless Sopwith Camel in 1920 and then from October 1925 not only releasing, but also recapturing aircraft in the air. A specially developed trapeze was attached to the envelope from which was suspended a DH53 Hummingbird lightweight singleseater. When R33 had attained a height of 3800 feet (1150 metres), Squadron Leader Rollo Amyat de Haga Haig climbed down a ladder into the cockpit, the trapeze swung down and the Hummingbird, J7326, was released. He dived until the engine started, performed two loops and returned to the airship to hook on. As he came in to engage, the aircraft touched one of the trapeze stay wires and the propeller was smashed. The pilot then disengaged the suspension gear and dropped down to glide to Pulham airfield below. On investigation it was decided that the approach of the pilot had been incorrect and the trapeze should have only been lowered when he was approaching from the stern, then there would have been a perfect approach with the nose gear slotting easily into place. The second attempt was also imperfect and once more the pilot landed on the ground. The third try, on 4 December, was completely successful, flying J7326. The following year the same experiment was made with a pair of Gloster Grebe II fighters, J7385 and J7400; both were dropped successfully in October and November, but no attempts were made to hook on again. The first successful launch was achieved on 21 October 1926. The pilot was Flying Officer R.L. Ragg (Later Air Marshal, CB, CBE, AFC) of the Royal Aircraft Establishment.

R23 and Sopwith 2F.1 Ship’s Camel N6622 in the shed at Pulham in 1918. It was also launched successfully and flown by Lieutenant Keys. Note C*9 in the background.

R23 and Camel N6814.

DH53 Hummingbird J-7326 suspended from R33 during trials in 1925.

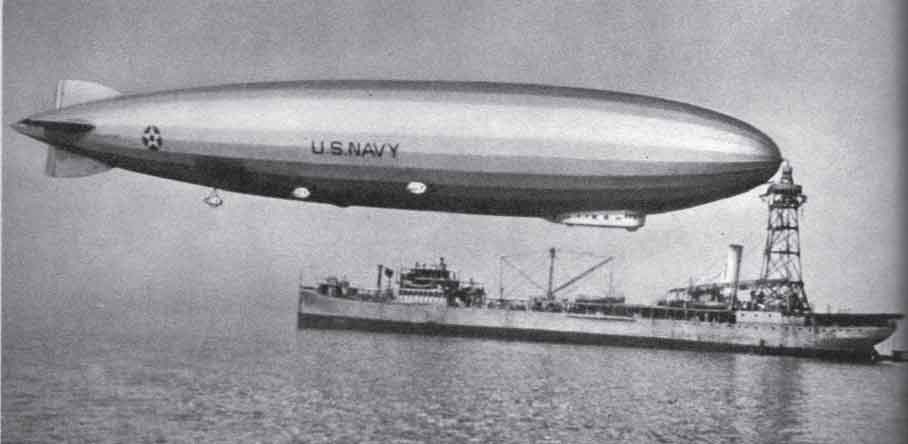

The most persistent and effective users of this idea were in the USA. The US Army Air Service experimented in 1923–1924 with a Sperry Messenger and Army Corps blimps TC-7 and TC-3, conducting numerous flights achieving successful launch and recovery. The US Navy devoted a great deal of time and resources to examining the possibility of using airship-borne aircraft as fleet scouts. Tests were conducted using the USS Los Angeles. A rigid ‘trapeze’ was installed on the airship and a programme of flights was undertaken from 1929 onwards, the first successful ‘hook on’ being made on 3 July 1929 by Lieutenant A.W. ‘Jake’ Gorton, flying a Vought UO-1.25 In January 1928, the Los Angeles had also made a successful flight some 100 miles (161 kilometres) out to sea off the coast of Rhode Island, to land on the deck of the seaplane carrier, the USS Saratoga; she then followed up in March with a flight of 2265 miles (3624 kilometres) in forty hours from Lakehurst, New Jersey, to Panama, Cuba and back.26

The USS Akron’s design included a hangar aft of the control car and crew’s quarters. At the time of her early flights, however, no aircraft were carried. In February 1932 a trapeze was installed. Unlike the device on the Los Angeles, it included a winch which allowed the hooked-on airplane to be hoisted through a T-shaped door into the belly of the airship, where it was then transferred onto an overhead trolley system and rolled into one of the four spaces provided in the hangar. The hook-on operations began in May 1932. On 4 May 1932, a Consolidated N2Y-1 successfully hooked on to the Akron’s trapeze and was hoisted inside the giant airship’s hangar.

USS Los Angeles moored to USS Patoka.

The USN then ordered a new design of aeroplane which many have believed was specifically for the role of airship operations, the Curtiss F9C-2 Sparrowhawk. It was in fact developed from a specification for a very small carrier-borne fighter.27 It was a stubby little aeroplane and could fit inside the airship’s hangar, and was first hooked-on to the Los Angeles in October 1931. The training carried out included night hook-ons for which the only illumination of the trapeze was by hand-held flashlights.28 The Heavier-than-Air Unit of ZRS4 and ZRS5 began operating as scouts from the Akron the following year, but as mentioned above, the airship was destroyed in 1933. It had been discovered that the process of hooking-on required no extraordinary flying skills. The relative speed of the airship and the aeroplane were almost zero, the pilot approached the trapeze in an almost stalled attitude and slid his skyhook over the yoke of the trapeze. A spring-latch prevented him from drifting back off the yoke. If he stalled completely during his approach, he had at least 1000 feet (404 metres) of altitude in which to recover and then try again. Taking off was even easier, he simply pulled a lever in the cockpit to release the skyhook. The USS Macon also had provision for Sparrowhawks. They proved to be a success in scouting up to 200 miles (320 kilometres) ahead of the airship and their range was extended by removing their landing gear during over-water operations, replacing this with a belly fuel tank, which increased the aircraft’s range by fifty per cent. On 19 July 1934, just how effective they could be was demonstrated. President Roosevelt was aboard the cruiser USS Houston, steaming west across the Pacific towards Hawaii. At noon, to the astonishment of the ship’s crew, two tiny aircraft were spotted diving toward the ship, which they then circled – to the President’s delight. As they were more than 1,500 miles (2400 kilometres) from land it seemed impossible that any aircraft could have the range required to operate so far from base. No aircraft carriers were operating anywhere nearby. Then Macon appeared overhead and orchestrated a series of demonstrations, during which the aircraft dropped mail and messages, which were recovered and winched into the airship’s hangar. The President radioed the airship’s commanding officer congratulating him; it had been a highly effective piece of publicity for the US Navy. Sadly, all such experiments came to an end when the Macon too was lost. Remarkably, the crash site was found in 2006 and the wreckage of several Sparrowhawks was discovered on the sea bed. A plan to construct the much larger ZRCV, which would have carried nine dive-bombers, was never taken beyond the concept stage.29

On 7 July 1933 the first Sparrowhawks hooked on to the USS Macon.

A F9C-2 Sparrowhawk attached to the trapeze of the USS Macon.

Finally, in the spring of 1937, General Ernst Udet, flying a Focke-Wulf FW-44 Stieglitz made either one or two in-flight hook-ons to a trapeze fitted to the German Hindenburg. The aim of this project was to develop an aerial delivery system for mail or passengers. The trials were not wholly successful as Udet experienced considerable difficulty attaching the light training biplane to the trapeze in the turbulent air underneath the airship.

Conclusions

It remains to evaluate and to guess where Neville Usborne’s ability and desire for success could have taken him had he not met his untimely end. His ambition and technical ability took him to Barrow and HMA No 1, the ability he displayed there, despite the failure of the Mayfly, saw him posted to Farnborough, where he really learned to become an airshipman. Fortunately, the Royal Navy retained just enough of an interest in airships to allow Usborne to be in the right place at the right time, Kingsnorth, so that all that he had learned could be put into effect in the design of two highly successful classes of airship. Sadly his bravery and his questing intelligence, his desire to solve the pressing Zeppelin problem, resulted in his untimely and tragic death. He was admired by his peers, many of whom reached high rank in the RAF or the RN, or high positions in civil aviation. He was well-connected socially, ambitious, dynamic, commercially and mechanically minded, and also had the ear of a leading industrialist. In November 1915 Usborne drew up proposals for the formation of a post-war aeroplane company.30 He envisaged a small number of skilled designers working for a company which would supply aircraft, flying schools, repair facilities, the design of aerodromes, and which would acquire the rights for mail services to developing markets in foreign countries (eg South America). His fertile mind also considered USA to Europe mail and passenger services. He had concluded that airships would not be viable as a commercial success except perhaps for very long overseas journeys. He was by no means alone in this supposition. For example, on 3 May 1919, a regular columnist for the Belfast daily morning newspaper, the Northern Whig, who wrote under the pseudonym ‘An Old Fogey’, wrote an article entitled ‘Ulster’s Great Aerodrome’. He was moved to quote Lord Tennyson, who foresaw, ‘the nation’s airy navies grappling in the central blue,’ which had certainly been realised in the preceding four years, but he also looked forward to another of his lordship’s predictions coming to pass, ‘the heavens filled with commerce, argosies with magic sails, pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales.’ There then followed a speculative section entitled Commercial Flying; ‘Now the Air Ministry have published a map showing several routes for the guidance of pilots, and have issued a set of rules of the road and a scale of the charges to be made for the accommodation of civil aviators and their machines at government aerodromes, including Aldergrove. Transatlantic commercial flying, in the opinion of experienced aviators, will come in the near future and the importance of Aldergrove may be still further enhanced by its becoming an important transatlantic air station. Then we may expect announcements in our Saturday morning newspaper such as the following – “Belfast and New York Air Service – Departures from Aldergrove next week as follows: Thursday, Dalriada 3000 hp: Saturday, Ben Madigan 4000 hp: both Belfast built airships. For passage apply etc.’”

His letter of 7 January 1916 to Vickers, with his proposals for post-war aerial transport, received an encouraging reply from the chairman, Sir Trevor Dawson, who himself had been a gunnery officer in the Royal Navy in the 1880s and 1890. Success in the aviation business after the First World War was much on the minds of many of those who had gained vast flying experience during the conflict. Some tried breaking long-distance records, others joined the fledgling airlines and many more set up joy-riding companies. Few in the end made their fortunes. Two ex-military airmen were particularly successful; Sir Alan Cobham, who founded Flight Refuelling Limited after a decade of long distance flights and air displays all around the UK, and Ted Fresson, who was the pioneer of civil aviation in the far north of Scotland and the Isles. Perhaps Usborne could have joined this very short list, but it would have been a struggle. It was not until the 1930s that civil aircraft were designed in Britain that were sufficiently cost-effective to make running an airline in any way economically viable. Even then the biggest players were: the Government and Imperial Airways; the four big railway companies and Railway Air Services; and the investment house Whitehall Securities and British Airways. Industrially, Sopwith, Vickers, Handley Page, De Havilland, Avro and the rest survived on their wits, contracts for military aircraft, light sporting types from the late 1920s and civil airliners in penny packet numbers. If Usborne had gone into the administration of civil aviation, he might have prospered there, as did Sefton Brancker and Frederick Sykes. On the other hand many of his airship contemporaries rose to senior rank in the RAF or the Royal Navy; Masterman (1880–1957) and Maitland (1880–1921) were both Air Commodores, Elmhirst (1898–1982) became an Air Marshal, Sueter (1872–1960) a Rear Admiral, and both Bell Davies (1886–1966) and Usborne’s own brother, Cecil, (1880–1951) reached the rank of Vice Admiral. It is safe to say, I believe, that he would have made a lasting mark and would not be such a forgotten figure.