6

The Consumer Knows Best

When medicine appears to the user to be a “free” good, there is no limit to the amount demanded….Inevitably, people who are well connected, hypochondriacs with time on their hands, and the simply persistent get an undue share.

—Milton Friedman, 19751

The United States has a health-care problem. In 2014, total spending on health care amounted to more than one-sixth of the entire economy—more than $9,500 per person. That’s twice as much, in dollar terms, as in the average developed country.2 Yet we do not get particularly good medical care; according to most measures of quality, the United States falls in the middle of the pack. Nor are we unusually healthy. Life expectancy for Americans is 78.8 years, 1.7 years less than the average in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)—a group that includes both the world’s advanced economies and some developing countries such as Chile, Mexico, and Turkey. In a recent evaluation of eleven rich countries by the Commonwealth Fund, the United States came in dead last in overall health outcomes and led all countries in inequality of access to care.3 Life expectancy for the richest 1 percent of Americans is ten to fifteen years longer than for the poorest 1 percent—a gap that has been widening since the beginning of the century.4 How can we spend so much money and get such dismal and unequal results?

Too Much Free Stuff

If you’ve taken a little bit of economics, the answer is obvious: Americans don’t pay enough for their health care. Politicians may bemoan the fact that tens of millions of people are uninsured, but the real problem is that we have too much insurance of the wrong kind. With insurance, you don’t pay the full cost of your care at the time that you decide to see the doctor, take a test, undergo surgery, fill a prescription, buy medical equipment, or check into the hospital. Depending on your plan and the service provider you visit, you might pay nothing, or a flat $30 co-payment for each service, or “co-insurance” equal to 20 percent of the price, or the full price up to a $1,000 annual deductible, or something else. As a result, most people don’t know the full cost of their health care—and they aren’t really interested, because they pay just a fraction of it.

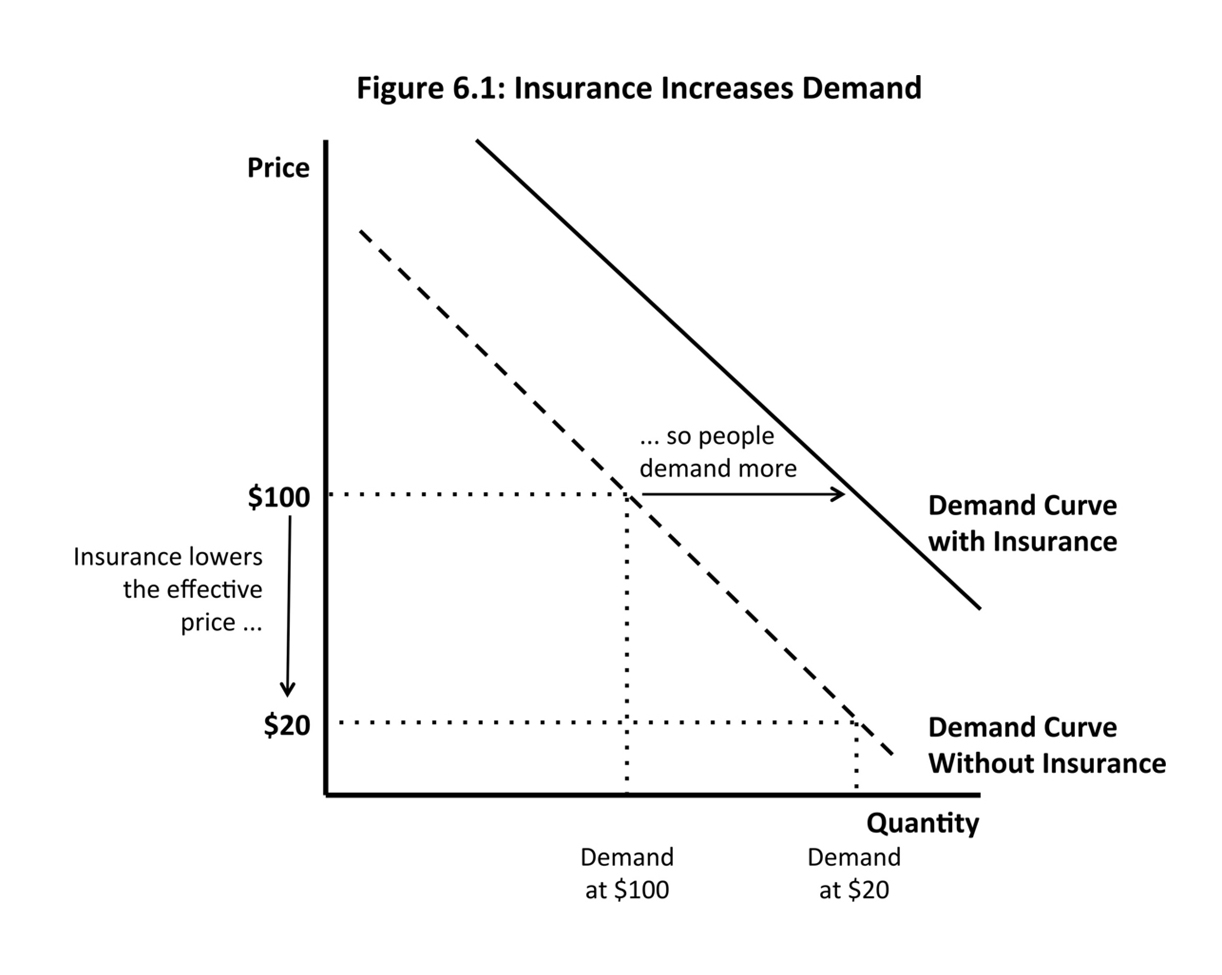

In Economics 101 terms, insurance increases the demand for health care. Let’s say that you pay 20 percent of your medical bills and your insurer pays the other 80 percent. That means a $100 doctor’s visit only costs you $20. Your demand for doctor’s visits is based on your net price of $20, so you consume more than you would if you paid the total price of $100. Everyone behaves this way, so the demand curve shifts outward, to the right (Figure 6.1), and both the price and the quantity of health care go up (Figure 6.2).

Because insurance lowers the perceived cost of health care, people end up consuming services that provide less value than they cost to deliver. Let’s say you are feeling just a little sick, so seeing the doctor is worth $30 to you.*1 You only have to pay $20, so you go, but the total price is still $100, because the insurer is paying $80—a cost ultimately borne by all of its customers in the form of insurance premiums. The net social welfare of this appointment is negative because its cost exceeds its value to the consumer. Multiply this one example by all the people with insurance, and the economy ends up producing too much health care (as shown in Figure 6.2)—too many unnecessary tests, too many surgeries of dubious value, and so on—at too high a price. That’s the problem with the American health-care system, according to economism.

If the problem is too much demand, the textbook solution is that people should bear more of the true costs of their consumption. Instead of those costs being shared across many people in insurance premiums—which you pay every month regardless of your behavior—you should face them every time you decide to go to the doctor, refill a prescription, or get an MRI. This way, you will only buy services when their value to you exceeds their cost to society. If you have to pay $100 to see the doctor, you will only go if it is worth $100 to you. This is how the rest of the economy works, after all: Apple produces exactly the right number of iPads because people buy them only if they will get more than $499 of value from them. Not only will exposing people to the full marginal cost of their health care solve the problem of overconsumption, but also it will stimulate competition among service providers, which will only be able to increase profits by lowering costs or providing more value to customers. In the terms that Ludwig von Mises used in Bureaucracy, consumer sovereignty will ensure that the health-care sector as a whole provides the services that consumers prefer, as efficiently as possible.5 Making people responsible for their choices will make society as a whole better off.

CONSUMER-DRIVEN UTOPIA

Economism’s preferred solution, therefore, is to apply the competitive market model to health care. As the economists John Cogan, Glenn Hubbard (chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush), and Daniel Kessler confidently asserted in a 2004 Wall Street Journal article, “Free markets are a proven way to discipline costs, encourage innovation and increase quality. The starting point to fixing the health-care system is recognizing that a handful of existing public policies prevent markets from working, and then changing them.”6 Economism’s utopia goes by the name of consumer-driven health care: a system in which people behave like discerning shoppers because they bear the cost of their decisions, and their choices provide the incentives for businesses to offer superior services at lower prices.

The simplest way to make people recognize the real cost of their health care would be to eliminate insurance altogether. Without insurance, however, many people diagnosed with serious diseases would be unable to afford appropriate treatment. Most policy proposals take a less extreme form, featuring health plans that mandate greater cost sharing: mechanisms that require people to pay out of pocket for expenses as they incur them. Cost sharing can take the form of co-payments (flat fees per service), co-insurance (a percentage of the total price), or an annual deductible (an amount a participant must pay before receiving any benefits). Advocates of consumer-driven health care are particularly fond of “high-deductible” plans that require people to pay as much as $10,000 out of pocket before full coverage kicks in. The idea, as Cogan, Hubbard, and Kessler put it, is that “higher copayments will give consumers more ‘skin in the game,’ making them more cost-conscious and more willing to take greater control of health-care decisions.”

All other things being equal, people tend not to like cost sharing. According to Economics 101, however, greater competition among insurers should shift the market toward consumer-driven plans. In a competitive market, people (or companies that provide health benefits for their employees) will shop around to find the cheapest acceptable insurance. Because plans with more cost sharing turn policyholders into smarter consumers (in theory), they reduce unnecessary consumption, which translates into lower insurance premiums. Therefore, individuals and employers will choose high-deductible and other consumer-driven plans. In the end, health care will become more like a textbook market in which consumers, by only buying what they are willing to pay for, ensure they are getting value for their dollar, which in turn encourages beneficial competition among service providers.

For the past quarter century, consumer choice and market competition have been central themes in health-care policy debates. As Stuart Butler of the Heritage Foundation said in 1993, “If people don’t experience the actual cost of an item—or service or benefit—they tend to want as much as is available.” Instead, the health-care system should be based on “the foundations of a market economy—consumer choice, competition, private contracts, and market prices.” The CEO of CIGNA, a major insurer, said while promoting consumer-driven health care, “What didn’t work in managed care [a system with little cost sharing, in which services are limited by health maintenance organizations] was that we separated the consumption of care from the cost of care. People didn’t care what things cost anymore.”7

“Choice” and “competition” have become magic words on both sides of the political aisle. On the campaign trail in 1992, Bill Clinton adopted the idea of managed competition, which an industry trade group called “a private-sector approach to health system reform that uses the marketplace and the power of informed consumer choice to achieve better coverage, while improving quality and cutting cost.”8 His 1993 health-care proposal was designed to allow individuals to choose among competing insurance plans offered through regional cooperatives—abandoning the universal government insurance model championed by Democrats for decades and embodied by Medicare, the federal health plan for seniors. For Republicans and some Democrats, however, the Clinton plan still involved too much government coercion, regulation, and bureaucracy. Under assault by politicians, industry groups, and talk radio hosts, it died an ignominious death without ever coming to a vote.

Clinton’s successor, George W. Bush, promoted high-deductible plans coupled with health savings accounts—tax-sheltered accounts that can be used to pay for out-of-pocket expenses—because “empowering consumers is essential to improving value and affordability.” In his ideal system, “competition and market forces…would be relied upon to improve the quality and efficiency of health care and to reduce the growth of health care costs.” As Merrill Matthews, then head of a health insurer trade group, explained, “What the consumer-driven movement does is remove some of that insulation [from true costs], and give people the incentive to ask the question ‘Where do I get value for my dollar?’ ”9 Since getting a boost from President Bush, high-deductible plans have been growing in popularity among insurers and employers. In 2006, only 4 percent of workers were enrolled in high-deductible plans; by 2015, that figure had risen to 24 percent. Across all types of health plans, the average deductible has more than doubled since 2006.10

When Barack Obama became president in 2009, he was determined to expand health insurance coverage while avoiding the missteps of the Clinton administration. His signature legislative achievement was the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, better known as Obamacare—a reform package that sits politically to the right of the Clinton plan and that is similar to the program introduced in Massachusetts in 2006 by Governor Mitt Romney. (At the time, Heritage applauded Massachusetts’s “consumer-driven marketplace” for increasing choice, stimulating competition, and lowering costs.11) Obamacare requires people to get health insurance from their employers or purchase it on an exchange, where private insurers compete for customers. By bringing buyers and sellers of insurance together in regulated, transparent exchanges, the system attempts to harness the power of markets to make everyone better off.

President Obama tried to lay claim to the principles of choice and competition with his health-care plan. According to his opponents, however, he didn’t go nearly far enough, or he was simply lying. Since it was passed in March 2010, Republican politicians and conservative groups have been fighting to repeal the Affordable Care Act (with occasional support from Democrats opposed to specific provisions). When proposing alternatives to Obamacare, they typically assume that the health-care and health-insurance markets will behave according to the Economics 101 model. According to Heritage’s experts, “When individual consumers decide how the money is spent, either directly for medical care or indirectly through their health insurance choices, the incentives will be aligned throughout the system to generate better value—in other words, to produce more for less.” Their evidence for this claim is simply that this is how markets are supposed to behave: “In normal markets, consumers drive the system through their choices of products and services….In response, the providers of goods and services compete to meet consumer demands and preferences by supplying products that offer consumers better value in terms of price, quality, and features.” Researchers from the Hoover Institution and the American Enterprise Institute claim that, instead of Obamacare, “what’s needed is a credible plan to reorient federal policy across the board toward markets and the preferences of consumers and patients.”12

That plan includes not only repealing Obamacare but also rewriting Medicare according to Economics 101 principles. Since 2010, Republicans have been promoting the idea, first introduced by Paul Ryan, of converting Medicare into a voucher program: instead of simply being covered by a uniform government plan, seniors would get a voucher that they could use to buy insurance from private companies in a competitive market. “Putting patients in charge of how their health care dollars are spent will force providers to compete against each other on price and quality,” the proposal predicted. “That’s how markets work: The customer is the ultimate guarantor of value.”13

The rhetoric of markets has been picked up and amplified by the media. Wall Street Journal op-ed articles, for example, regularly sing the praises of consumer-driven health care. A CEO and a Manhattan Institute researcher wrote,

As millions of Americans move onto high-deductible plans, they will change their behavior—and the incentives of the market….Providers will have to earn their business on the basis of quality, price and service, the way companies do in the other four-fifths of the U.S. economy. Competition has the potential to transform America’s sclerotic, overpriced health-care system into something much more transparent and affordable.

The head of another conservative think tank claimed that, if Medicare were converted into a voucher system, “Insurers would have to compete for beneficiaries’ business, and providers would have to compete to get on the most popular plans. Lower prices and better-quality care would be the result.”14

In the 2016 presidential election, not only did all Republican candidates ritually pledge to repeal Obamacare, but most subscribed to the principles of market forces and consumer choice. Marco Rubio promised “modern, consumer-centered reforms that lower costs, embrace innovation in healthcare, and actually increase choices and improve quality of care,” including “consumer-centered products like Health Savings Accounts.” Rubio, Ted Cruz, and Rand Paul all signed the “Contract from America”—an initiative of FreedomWorks, Americans for Tax Reform, and other conservative groups—which called for replacing Obamacare with “a system that actually makes health care and insurance more affordable by enabling a competitive, open, and transparent free-market health care and health insurance system.” Rick Santorum promised to expand health savings accounts “to give patients and doctors, not Washington bureaucrats, more freedom and control over their health care.” Even Donald Trump, who in a prior life favored a universal health insurance system, has adopted the language of competition and choice: “We still need a plan to bring down health-care costs and make health-care insurance more affordable for everyone. It starts with increasing competition between insurance companies. Competition makes everything better and more affordable.”*2 15

BAD CHOICES

It seems convincing. Of course health care should behave like any other market, so of course people should be required to pay the full cost at the point of care to ensure that they make smart decisions. In fact, however, health care does not behave like any other market (putting to the side the question of whether any market behaves the way it is supposed to in Economics 101)—something economists have known for decades.

Kenneth Arrow, one of the towering figures in modern economics, in 1963 wrote a canonical paper explaining why health care does not behave like a textbook market. The most obvious anomaly, he emphasized, is that we do not incur medical expenses regularly. In fact, we rarely need most forms of health care. When we do need them, we need them badly, however; illness itself can be costly, both in lost income and in reduced quality of life, even before the high cost of medical treatment. Because we are not regular consumers of health care, we lack both the knowledge and the experience necessary to be smart shoppers. If you are diagnosed with a severe condition, you may have to choose among a variety of treatments that meant nothing to you the day before while facing a huge degree of uncertainty about their outcomes.16 You can’t rely on your friends’ recommendations, because many medical situations are unique and even people who have recovered from similar illnesses are unlikely to know exactly why. If you do your own research on different treatments and providers, you will struggle to find useful information. As the health economist Uwe Reinhardt describes it, “The usual absence of reliable information on the quality and prices of health care available to consumers…effectively converts them into blind-folded shoppers in a bewildering shopping mall.”17 These are all reasons why people tend to put themselves in the hands of their doctors rather than trying to become experts themselves and why informed consumer choice is rare in the medical sphere.18

The inability of real people to make good medical choices turns out to be the Achilles’ heel of consumer-driven health care. The landmark RAND Health Insurance Experiment, which followed close to three thousand families in the 1970s and early 1980s, showed that higher levels of cost sharing “reduced the use of effective and less-effective care across the board.” Multiple subsequent studies have confirmed that “cost sharing is as likely to depress appropriate care as it is to depress inappropriate care,” as the health law professor Timothy Jost concluded. A recent research paper found the same was true of high-deductible plans: when a company switched tens of thousands of employees from a traditional PPO (preferred provider organization) plan to a high-deductible plan, they reduced consumption of both valuable and wasteful procedures, with no evidence that they sought out lower prices for services.19 In other words, higher cost sharing does get people to buy less health care in the short term but does not make them better at getting value for their money. In the words of the health economist Meredith Rosenthal, “[Consumer cost-sharing] will save money, but we have strong evidence that when faced with high out-of-pocket costs, consumers make choices that do not appear to be in their best interests in terms of health.”20 While people may buy too much health care under current insurance schemes, high-deductible plans present a different risk: that they will not buy enough care, or will not buy the right type of care, to their own detriment.

In the long term, the result can be worse health outcomes and higher total costs, particularly when people try to save money by cutting back on preventive care or medications for chronic illnesses. In his review of the empirical research, Jost found ample confirmation that “increased cost sharing can have adverse health effects.” One study found that when people were switched into high-deductible plans, their primary response was to cut back on prescription drugs for chronic conditions; this was true even when prescriptions were exempt from the deductible (that is, such drugs were covered before participants reached the deductible), indicating that people are not the rational value maximizers that consumer-driven health care expects them to be.21 In some cases, requiring people to pay more for medical care causes them to forgo valuable services or treatments. Higher levels of cost sharing make poor families several times more likely to skip seeing a doctor for their children’s asthma and are also correlated with a higher frequency of asthma attacks among children. When retired state employees in California faced higher co-payments, they cut back on both office visits and prescription drug utilization, as predicted, but hospital visits went up, particularly among the very sick.22 This implies that on the whole consumer-driven health care may not even achieve its goal of reducing total costs.

The Economics 101 model in which financial incentives turn people into discerning consumers turns out not to work in the real world. For Mises and Hayek, the crowning jewel of societal organization was the price system, which coordinates the activities of millions of people to deliver the most valuable goods and services to the most people. But in the market for health care, as Arrow said recently, “We talk about a price system, but that is not what we have. What we have is a system in which one buyer will pay ten times what other buyers will pay for similar medical devices, or services. So the idea of a price system as the source of efficiency fails at the most elementary level.”23

BROKEN MARKET

The fact that our health-care needs are unpredictable and potentially costly also means that people want to insure themselves against future expenses. As a consequence, the market for health care is inseparable from the market for health insurance. But, as Arrow explained, the insurance market suffers from its own profound failings: “A great many risks are not covered, and indeed the markets for the services of risk-coverage are poorly developed or nonexistent.”24

The private health insurance market is nearly fatally flawed. The goal of any insurance company is to predict how much a given person will cost in claims over the next year and charge a premium that more than covers those expected costs. The sicker the person, the higher the price. This is known in economics as price discrimination. In a competitive market, insurers will get better and better at figuring out how much you are likely to cost—by looking at your medical records, your genetic data, your purchasing patterns, and your online searches—so they can charge you the appropriate price. But if someone is likely to need $50,000 of health care, the appropriate price from the insurer’s perspective is more than $50,000, which most people obviously can’t afford. If you have a chronic illness, or your grandparents had expensive hereditary diseases, or you are simply old, the “correct” price could easily exceed your budget.25

If insurers set a profit-making price for each person, the poor and the sick will be left without any coverage at all. Ordinarily, we think that competitive markets maximize social welfare: remember, if people get something that they can’t afford, the economy will produce too much of it. But this is not necessarily true of health insurance, which enables people to afford medical care that could be of great value to them and to society. If someone couldn’t afford a needed heart transplant on her own, but her insurance policy pays for the operation, that’s not an example of frivolous overconsumption; that’s a benefit for society, particularly if she goes on to work productively for decades. The health economist John Nyman concludes,

Because people value the additional income they receive from insurance when they become ill more than they value the income they lose when they pay a premium and remain healthy, and because everyone has in theory an equal chance of becoming ill, this national redistribution of income from the healthy to the ill is efficient and increases the welfare of society.26

If fewer people can afford insurance, society becomes worse off.

Most people are not prepared to say that poor people should go without health care, so there are various ideas about how to fix the insurance market. One way to prevent individuals from being priced out of the market is to prohibit price discrimination; Obamacare, for example, limits insurers’ ability to set premiums based on people’s medical status.27 But if everyone pays the same amount, the problem of adverse selection appears: insurance becomes unattractive to healthy people (who are being charged “too much”), so they refuse to buy policies, driving up premiums for the sick people who remain in the insurance pool, causing the less-sick people to decline coverage as well, pushing up premiums even further. Limiting price discrimination, therefore, creates the need for Obamacare’s individual mandate; by forcing everyone to buy insurance, you can require the healthy to subsidize the sick. Even then, the cost of insurance remains too high for poor families. Remember, average health-care spending is more than $9,500 per year, while a person earning the minimum wage only makes about $15,000. For the working poor to afford insurance, there must be explicit redistribution from richer families—such as the Obamacare subsidies for low-income households. Finally, if everyone pays roughly the same price, individual insurers have the incentive to “cherry-pick”—to attract healthy people while deterring sick people from applying. To make the system work, Obamacare includes a complex risk adjustment mechanism that shifts money between insurance companies based on how sick their customers are.

In an ordinary market, the people who consume the most services should pay the most money; applied to health care, however, that principle would produce morally intolerable results. Therefore, in the real world, the market must be hemmed in by regulations that limit insurers’ ability to maximize profits and prevent individuals from opting out of the system. The point of all these constraints is to separate the premiums charged for a health insurance policy from the actual cost of underwriting that policy so that poor and sick people can buy coverage that a textbook market would deny them. This is how we end up with a barely tolerable system in which most people get some coverage at a price that isn’t too unaffordable.

Cost sharing, however, strengthens the link between the amount of health care you use and the amount you pay. Indeed, for advocates of consumer-directed plans, that’s precisely the point. Compared with other types of insurance, plans with high levels of cost sharing transfer money from sick people, who pay more out of pocket, to healthy people, who benefit from lower monthly premium payments. And the increase in cost sharing over the past decade has had a predictable impact on low- and moderate-income families. About one in five people with private health insurance currently has difficulty paying medical bills. For the large majority of this group, the problem is not that evil insurance companies denied their claims but simply that their policies required them to pay too much out of pocket. Not surprisingly, people with high-deductible plans are much more likely to have trouble with medical costs than are people with other plans.28 As the economist Jerry Green summarized, “It’s equivalent to taxing the sick.”29

The more you rely on the principles of the market, the more you have to accept its distributional consequences. This is the fundamental problem with consumer-driven health care. Higher cost sharing makes economic sense, at least in theory—if we think that health care should be delivered through a market. It makes sense that price signals would encourage people to make smarter choices (leaving aside whether they actually behave that way) and force service providers to be more efficient. But if we rely on a competitive market to provide health care, then everyone will get the care that she can afford. For people who are steeped in Economics 101, this is a good thing; how else could we maximize social welfare? But for many people with traditional moral sensibilities, the idea that the rich will have access to life-extending therapies, the middle class will scrape by, and the poor will go untreated except in an emergency is simply wrong. “Most of us think it’s fine that some people can’t buy fancy clothing or fast cars,” the political scientist Jacob Hacker writes. “But most of us draw the line at basic health care.”30

Perhaps the most fundamental lesson of Economics 101 is that competitive markets, in which prices are determined by supply and demand, are the right way to allocate resources and distribute goods and services. Even when there are specific market failures (such as adverse selection), the recommended solution is to correct for those discrete problems (for example, by requiring everyone to buy insurance), which will restore the market to its ideal state. One of the most sweeping triumphs of economism has been to convince both sides of the political debate that this fundamental lesson applies to health care. Virtually all Republican politicians favor deregulation and consumer-driven plans because they think that health insurance and health care can and should be delivered by a textbook competitive market. Most Democrats actually agree that health insurance and health care should be delivered by markets; they disagree only on the extent to which regulations should attempt to correct for predictable market failures. The result is Obamacare: a jury-rigged patchwork of mandates, regulations, taxes, subsidies, and risk adjustment mechanisms intended to force markets to produce a socially acceptable outcome—one in which most people can afford something approximating decent health insurance.

THE FORGOTTEN ALTERNATIVE

The current system provides widespread but not universal access to health care by (a) selling insurance in “competitive markets,” (b) forcing everyone to buy it, (c) providing subsidies to people who can’t afford it, (d) limiting the policies that insurers are allowed to sell, (e) restricting their ability to set prices, (f) subsidizing employer-sponsored plans because companies can get better deals than individuals, (g) penalizing people who get plans that we don’t like, and (h) reshuffling money among insurance companies. Surely, there must be another way.

Not only is there another way; it’s one that every other country in the developed world has chosen. The alternative is a universal health insurance system, paid for by taxes and either administered or overseen by the government, in which access to most health-care services does not depend on ability to pay. Different versions of this basic model exist around the world. In the United Kingdom, most services are provided for free or with minimal cost sharing by the National Health Service, which is mainly funded by general tax revenues. In Canada, most care is paid for by universal health insurance programs administered by provincial governments and financed by general tax revenues. In France, coverage is provided by nonprofit insurance funds and paid for mainly by payroll taxes. In the Netherlands, people must buy basic insurance from private companies (similar to Obamacare), but their policies are effectively financed by a payroll tax.31 Although the role of the private sector varies from country to country, the unifying theme is that everyone is covered, mainly through taxes, with mechanisms to keep cost sharing at affordable levels. These systems are all based on the common principle of “mutual responsibility of citizens for the health care of each other,” in the words of Daniel Callahan and Angela Wasunna.32

In the United States, the most common label for this type of system is “single payer,” because one entity would pay for most health-care expenses. (The term is not entirely accurate, because some countries actually have multiple payers even for basic services, but they are so heavily regulated that they essentially behave the same way.) If the goal is to make health insurance affordable for everyone—something no politician would deny—the most direct solution is to have a universal, government-sponsored health plan with no up-front premiums, funded primarily by general tax revenues. Such a plan could have modest deductibles and co-payments intended to influence behavior at the margins, while still keeping out-of-pocket expenses manageable for everyone. It could also allow private insurance companies to sell supplemental policies to people who want additional coverage beyond the basic plan. In fact, the United States already has a single payer program: it’s called Medicare, it serves fifty million people, and it’s extremely popular.

Single payer, or a variant of it, will not magically solve all of our problems. In any system, there must be some mechanism to determine which people get what services—to “ration” health care, to use the dirty word. In a competitive market, it is prices, and therefore the rich live longer and more comfortably than the poor. In a government-run plan, it is statutes passed by legislators and regulations written by appointed officials and career civil servants. The question is which system can do a better job at delivering the most valuable health care to the largest number of people, in a morally acceptable way and at a reasonable cost.

There are reasons to be skeptical about single payer. The regulations necessary to implement such a system could end up enriching private interest groups with disproportionate influence over politicians (think about doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and medical device manufacturers) rather than improving the health of ordinary people. The bureaucracy that administers the system, unchecked by the pressure of competition, could impose its own layer of additional and excessive costs, as Friedman feared.33 In addition, if a single payer plan is successful in reducing spending, that could result in fewer people wanting to become doctors and fewer health-care providers investing in new technologies.

Evidence from around the world demonstrates, however, that these challenges can be successfully overcome. Every other rich country in the world has a health-care system that is much closer to the single payer model than to the competitive market model, and they generally fare pretty well. Of the thirty-four countries in the OECD, only Chile relies more on private insurance and out-of-pocket spending to pay for health care than does the United States; in every other country, government spending, including social insurance systems, plays a larger role. On the whole, these countries enjoy health outcomes comparable to or better than those of the United States. Of the OECD countries, the United States ranks between twentieth and twenty-ninth on primary health status metrics, ranks in the bottom third for access to coverage, and has among the fewest doctors and hospital beds per capita.34 As discussed above, we earn these dismal results despite spending by far the most money on health care. In this light, it seems quite possible that our high costs relative to the rest of the world are the result not of overconsumption but of a decentralized system organized around private profits rather than strong government spending controls.35 Finally, contrary to Friedrich Hayek’s dire warnings, public administration of health care has not led to an inexorable descent into totalitarianism.36

Competitive markets and single payer reflect two different ways of thinking about health. On the one hand, we can think of health-care services as discretionary consumer purchases that should be allocated via the forces of supply and demand, which will ensure that resources are directed efficiently toward those people who value them most (in dollar terms). On the other hand, we can think of illness and injury as unpredictable, expensive risks that all of us face and that we have an equal right to be protected against. The remarkable thing is that American political debates and policy discussions are dominated by the competitive market model, with one side saying it should be wholeheartedly embraced and the other saying that it should be redirected through judicious regulations.

This imbalance is a testament to the power of economism. Economic theorists and researchers have long recognized the unique characteristics of health care and the shortcomings of consumer-driven plans. As the economist Burton Weisbrod put it, “We cannot construct wise public policy on health care by applying elementary economic analysis. Competition does have a role to play. Yet the markets for health care and chocolate chip cookies are different.”37 Nevertheless, the basic idea that markets must know best has been accepted across most of the political spectrum. The result has been to drastically truncate the range of potential solutions to our current health-care problems, leaving the avowed socialist Bernie Sanders one of the few politicians willing to question the Economics 101 orthodoxy. The outcome is exactly what the health economist Thomas Rice warned against when he wrote,

If analysts misinterpret economic theory as applied to health—by assuming that market forces are necessarily superior to alternative policies, and that other tools of the trade neatly translate to health care—then they will blind themselves to policy options that might actually be best at enhancing social welfare, many of which simply do not fall out of the conventional, demand-driven competitive model.38

With steady price increases making health insurance and medical care unaffordable for a growing number of families and businesses, one commonsense response would be to treat health care as a basic right that is collectively funded by all of society. Instead, policy proposals focus on making markets more efficient, which necessarily shifts costs onto the sick.39 The result is “rationing by income,” as Reinhardt puts it:40 the rich can afford whatever they need when they fall ill, while the poor may have to choose between medications, utilities, car payments, and rent. High out-of-pocket costs increase the financial strain on families when they are least able to withstand it; about one-fifth to one-fourth of all household bankruptcies are primarily caused by medical expenses.41 Our high level of income inequality may be more tolerable if all people can afford basic necessities, including health care. Today, however, low-income families are increasingly finding that even having insurance is not enough to pay for the services and medications they need, while the rich continue to enjoy the best care that money can buy.

The greatest power of a worldview is to set the boundaries of what people believe is even possible. In The Problem of Unbelief in the Sixteenth Century, the French historian Lucien Febvre demonstrated that the mental world of early modern Europe was so saturated with religion that it was essentially impossible to be an atheist in the modern sense.42 Economism plays a similar role in contemporary American health-care debates, narrowing the window of possibility to different variations on the competitive market model taught in Economics 101—and blinding people to the lessons of the world around us.

*1 This may seem unrealistic, but Economics 101 assumes that you can estimate the dollar value to you of seeing the doctor.

*2 In the campaign, Trump endorsed a laundry list of standard Republican proposals based on “free market principles,” including greater competition in the insurance market, health savings accounts, and tax deductions for individual insurance premiums.