Finding Your Passion . . .

Again and Again

and Again

First of all if you have a camera around your neck

that’s basically a license to explore.

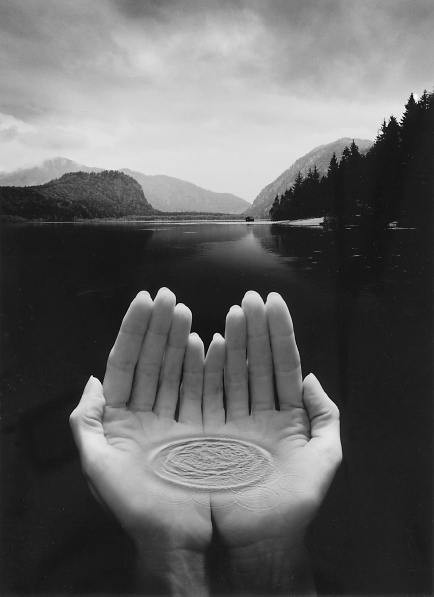

—Jerry Uelsmann

Change doesn’t only occur when we are faced with something catastrophic in our lives. It can happen silently over a period of time, building momentum until it morphs into something totally unexpected. Creative people need to be aware that there must be an element of their passion associated with every type of change they encounter. Without that element of passion, they will find something lacking in their new role, and it will leave them unsure of themselves, unbalanced in the universe, unable to feel complete. Our passion, no matter what form it takes, has to be acknowledged, accepted, nurtured, and shared, over and over again—and with each completion of this cycle it grows more powerful, and more unique. If we ignore it, it goes into hibernation, waiting for us to give it the respect it deserves. In this chapter we will look at several ways in which you may consider how well you are attending to the call of your passion, and how others have kept their passion alive through challenges not unlike your own.

As was mentioned at the end of the last chapter, it is imperative for us to consider our personal work history in order to gain an understanding of how we have, or have not, dealt effectively with the transitions we have chosen, or have been forced to choose. One of the great joys of writing this book is that I have had the good fortune to interview some of my heroes of photography and ask them to take a look back on their careers, so we might all gain some insights. The following is one such refreshing look back, taken from a conversation I had with Pete Turner. What was most revealing in this interview was that Pete presented the events that changed his career as if they happened because he was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time, when, in fact, it seems he positioned himself to be in the right place and waited for the right time to express his passion. Louis Pasteur said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” As you will see, Pete prepared himself, always keeping his passion as a main consideration for any decisions he made. Pete had a little chuckle in his voice throughout the entire interview, a chuckle that revealed the joy with which he approaches his work. You can’t hear it as you read the printed page, but you can definitely sense the enthusiasm he brings to his work everyday.

I innocently asked Pete this simple question: “What did you do to make a living before you became a photographer?” The following is his amazing story:

Pete Turner: Coconut Woman

I countered with, “Well, you know, everybody articulates it differently, but the beauty of what’s going on with this inquiry, with these interviews, is to start seeing the similarities. I mean we all approach the world differently, but if we are driven by that passion, that thing that just shakes you awake in the morning, and you say to yourself, ‘Wow, am I a lucky son of a gun or what?’ Sure there are tough times; but if you are honest to your passion, and you persevere, and you are open to ideas, there’s no telling where it can take you.” Pete responded: “I don’t blame people for the negatives. I’ve had them myself. Everything is not sugar coated. I can hate digital. Or I can love digital and hate traditional photography. It’s always a yin and yang for me, because with traditional photography you are stuck with film that a chemist has decided what the color balance is going to be and how the colors are going to look. With digital you’re not and you can throw in a palate that can be anything you want.

Pete Turner: Shapes of Things to Come

“I think that where we started earlier in this discussion is that it is all about change. Whether we like it or not we’re going to be yanked by change right through our whole lives. Change is here to stay.”

There are a lot of things we can learn from Pete’s story. The first thing that jumps out at me is that he managed to keep his passion alive right from the beginning. He loves color, he loves form, he loves travel, he loves exotic places and things, and he loves being there to record and interpret it all in his unique way. He always seems to be standing on the street corner with his camera at the intersection of desire and opportunity.

At one point in my career, it occurred to me that I could assist people in appreciating the roots of their passion by helping them visualize their past experiences so they could isolate and recognize their periods of creative highs and lows. If they could see their circumstances more clearly, then they could strategize, and possibly avoid—or at least minimize—the ennui of the Plateau of Mediocrity, and maybe even bypass the Valley of Despair altogether. If early on I had created a timeline of my career’s progress, I believe I could have been more proactive—and I could have been more productive, more prepared for the inevitable encounters with change. This may seem like pie in the sky thinking, but I’m talking about developing a way in which one is not constantly looking over one’s shoulder, but instead is using past experiences as a means for looking ahead, without losing sight of what one cares passionately about. This task requires the combination of a storyteller’s talent and a designer’s ability to conceptualize visually. The storyteller provides the narrative, and the designer takes all the historical data and fashions a comprehensible chart, map, or representation. One can then stand back and meditate on the choices one has made in one’s career.

For example, when starting out on any major new project, I like to spend a little time sketching—first on a notepad and then more formally on a big easel—a visual representation of where I am now and my eventual goal, so I can begin to make lists of things to prioritize. Then I can begin scheduling the times when things have to be accomplished and the milestones that will eventually have to be met.

For this endeavor, I figured anyone who was interested in creating a career map, if you will, would need a representation that would synthesize data from their own past. This, in turn, would allow them to take a hard look at that data in the clear light of the present, and would give them the freedom to consider the feasibility of what they want for their future—the stuff of their dreams.

The Work-History Timeline and the Personal Timeline

When I start working with a client, the first assignment I have them execute is the creation of personal and work-history timelines. This lets us get a perspective on where they have been in their careers, what they consider to be their important accomplishments, and also what distractions and obstacles they have encountered along the way. I tell them they can design it any way they choose, but it must have a baseline, time segments, and anything they consider as significant events in their work history, such as new jobs, promotions, new clients, achievements, problem times, resigning a client, leaving a job—in short, anything that prompted a change in career direction. We start out with the work-history timeline because it is the easiest to comprehend.

I remind my clients or students they can design their timelines any way they wish. This, in itself, reveals a great deal. Some will do a straight-line continuum that resembles the timelines you would see in a history textbook—Paleolithic, Neolithic, Bronze Age, etc. Others create a tree trunk, which illustrates their main form of expression, along with arabesque branches that show all the little excursions that caught their fancy along the way. And still others create a series of columns and lists, with titles like Education, Professional Experience, Skills, Accomplishments, Interests, as though they had taken their resume categories and turned them 90 degrees on their side. All of these visual expressions are equally relevant, because they help us to see our career experiences in a condensed perspective. We might visualize our lives as goal-oriented on a linear path, or as a series of episodes that have meaning only when looked at in their totality. Or maybe we see our lives as connections between hard work and destiny, somewhere between sweat equity and happenstance. Whatever the form, these work-history timelines give us a picture of a life with dimension, a life with alternatives.

Next, things get a little more complicated: I ask them to create their personal history timeline. Maybe you can, as one of my students did in a workshop, place your work experiences above the timeline, and your personal experiences below the line. The interrelationship was very revealing, as we could see a tug of war that existed between perceived allegiances. At times, work and personal histories could be seen as working cooperatively and in harmony with each other; at other times, there were tensions between work and family, or work and other interests.

Practically speaking, the timeline assignments are a reality check, because they reveal what a person feels is most important in his own shorthand way, because he assigns his personal level of importance to each event. The real significance of the timeline assignment is that it is a tool to get people talking. That talking leads to little self-revelations where priorities surface, and those lead to bigger truths.

Once the timelines are in place, the next thing to consider are the skills that have been acquired along the way. By studying the timelines it is relatively easy to begin listing the obvious and the not-so-obvious skills that came along with each experience. You may have good darkroom skills that helped enhance your digital postproduction skills. You might have shot photographs at first, then been asked to write a story to go along with the shots, so now you have journalistic abilities. Maybe you were asked to shoot live action along with stills on several jobs, and have now broadened your image-capturing possibilities to include film or video. Skills don’t have to be exclusively technical in nature. They can include managerial, accounting, production, communication, interpersonal, and other professional skills. And don’t forget other skills that are important in our increasingly global economy, such as foreign languages and cultural awareness. Transferable skill sets can make the difference between a mediocre job and an exciting career.

List of Interests—The Roots of Passion

With the timelines and the skills list in place, the next step in our preliminary journey of self-discovery is the development of a list of interests. This is revealing because we voluntarily select our interests; no one forces us to do these things, and we do them because we enjoy doing them, plain and simple. Doing things voluntarily is at the base of passion, so it is important to understand why and how we are drawn to certain things and not to others.

So how do you find your passion? The answer is, you don’t find it. You allow it to find you, and you stay open to recognizing it when it comes your way. You can’t force it. You can urge it by educating yourself; you can attract it by immersing yourself in it; you can cajole it by practicing it—but you can’t order it to do your bidding. You have to prepare yourself for passion and wait for it to introduce itself to you. As a friend once told me, “If you are waiting for your ship to come in, then don’t wait at the airport.”

This is where the fine art of playing becomes such an important factor. When we first play at something we do so because it is enjoyable. At first we fool around with our newfound toy, and then we find we have lost all sense of time while being immersed in this new adventure. Eventually we can’t wait to be interacting with this thing that brings us so much joy. The adrenaline that kicks in gives us extra energy and we find we can keep playing beyond being tired. If we do well at our play, we praise ourselves or we get praise from others. Once we reach one threshold of satisfaction, we want more and we push ourselves harder. It is part of the Creative Ascent, the joy of newness, of discovery, of growth. Play is at the heart of passion because it encourages us to reach beyond our perceived limitations and set new goals. That is why the Plateau of Mediocrity is so discouraging: the newness becomes routine, growth is stunted, there is nothing left to discover. After a while, mediocrity cannibalizes what is left of desire and play becomes joyless hard work with diminishing returns.

You have to get back to the rudiments of play if you want to summon your passion. Many people have to look back to what they enjoyed in their youth to find their passion. Pete Turner instinctively knew that the combination of his fascination for the darkroom and his love of stamps and what they represented (color, design, and exotic travel) were deeply embedded in his creative psyche. From that foundation he nurtured his interests with technical knowledge, and that provided opportunities for him wherever he went, over a long period of time. Richard Avedon, who contributed so much to our industry, was quoted as saying, “If a day goes by without my doing something related to photography, it’s as though I’ve neglected something essential to my existence, as though I had forgotten to wake up.”

There are other simple questions that can open your mind to rediscovering your passion. I ask my students and clients to write down what sections do they instinctively gravitate toward when they go to the bookstore; or what kind of sites on the Internet they seek out; what kind of stations do they have preset on their car radios. They are simple questions, but the answers tell a lot about the person. In the bookstores, do they look for biographies or picture books, children’s books, or technical books? When they are online, are they searching out chat rooms or sports Web sites, financial news, entertainment gossip, or the latest fashion styles? Are they addicted to listening to the latest news reports, or political talk shows, or music on the radio (if so, what kind of music)? The deeper we go, the more we find out what is important, even if it seems trivial, because we keep returning to it—not because we have to, but because we want to.

As a kid I used to spend a lot of time during the summer in the city library. I grew large (I’ve never grown up; I’ve just grown large) in San Bernardino, California, where the summers are brutal and the library was safe and had the best air conditioning. My sister and I would check out large quantities of books as members of the various vacation book clubs for kids, and pretty soon I had gone through the suggested reading lists for children my age. I remember making up a game where I would slowly walk down the long aisles with my eyes closed, and pretend that I was sending out radar waves that would tell me when to stop. Then I would reach up on a shelf, randomly pull down a book, and read a few pages from the introduction. If the subject matter interested me I would read on; if it didn’t, I would put it back and continue with my game. That started me on a long interest in books and the exotic adventures and wide range of knowledge they contained. Eventually I found that there were certain sections that held more interest for me, and I would concentrate on the books those sections contained. In a way, the books spoke to me as long as I was ready to accept their calling.

Another revealing question is where do you like to go on vacation? Again the answers tell us if the person prefers to stay close to home or is adventurous. Does the person strike out alone or with others? To established destinations or to remote, exotic places? As a photographer, you could be earning a livelihood while taking pictures anywhere in the world, even your own backyard.

Another question to ask is, what are your hobbies, pastimes, and interests? Hobbies are a perfect example of something a person would do out of a universe of choices. Interestingly enough, Leonardo da Vinci used to create rebus games for his own entertainment. Imagine, Leonardo da Vinci needed entertainment! He would write a few words backward and in Latin, then draw little pictures in place of some of the words and create puzzles that needed decryption. That kind of mental exercise kept him nimble in his thoughts and allowed new thoughts to enter his mind—thoughts that were vastly ahead of their time. The brain processes myriad bits of information simultaneously, and from time to time it has to work in another direction, another dimension, then it has to have time for rest before it can come up with a new variation on an old theme or something entirely new.

Jerry Uelsmann, 1982

During an interview with Jerry Uelsmann, I asked him to talk about how he approaches a new project; does he plan what he is going to do or does he instinctively just let the process happen? Here is what he had to say:

His words caused me to ask a question that had haunted me for some time: “Do you ever have that feeling sometimes, when you are creating things and you look at it the next day, that you don’t know where the hell that came from?”

Jerry responded, “That happens a lot. I lecture a lot, and when I talk about the creative process I try to tell people that they’ve got to learn first of all that uncertainty and self-doubt are essential to the creative process. That as long as you are comfortable with what you are doing, you’ve been there before and you are simply echoing something that worked for you in the past.”

We must not overlook the importance of serendipity in discovering our passion. Serendipity is the ability to make accidental discoveries and that ability is at the heart of rediscovering your passion. If you are too committed to one outcome, you might overlook the alternative that is sitting in front of you. Barbara Bordnick, an internationally renowned portrait and fashion photographer, related this wonderful story of how she came to discover another subject matter and the rewards that “accidental discovery” have given her.

Jerry Uelsmann, 2003

Barbara Bordnick: Delphinium

Barbara Bordnick: Helen Humes, jazz singer

This, and many other stories like it, lead me to ask the question, are these discoveries accidental or are they more available than we think they are? Are we just too creatively myopic, or too rushed, to perceive them? Are we so bombarded with stimuli that we can’t see the worlds of wonder and possibility that are waiting right next to us? Barbara had the ability to see past the obvious setback of the scheduling mix up with the model and turn the situation into an opportunity, one that has been creatively and professionally rewarding.

Barbara Bordnick: Harpers Bazaar, 1969

One other very useful method, one of my favorites, for helping someone find the basic elements of their passion is to have them get involved in a mentoring program. I ask my clients, “If you could mentor people in your artistic field, what kind of class would you create for them?” Then I try to find that kind of program for them. The results are always personally and socially fulfilling, and the outcome is predictable. When an artist sees the light that comes into the eyes of a young person he is mentoring, then he relives the joy he himself has lost. Let me illustrate this with a story. I mentioned that I helped start a nonprofit arts program for children after the riots in Los Angeles in 1992. During our first meeting with a group of kids for a photography class, we were ill equipped for the number of kids that showed up and did not have enough cameras. One of the mentors came up with a brilliant idea. The mentor asked the kids to go back home, get some sunglasses, and then return. They all returned with all sorts of sunglasses. We took a grease pencil, drew a rectangle on the inside of one lens on each of the sunglasses and proceeded to deliver a class in one-point perspective. We then marched the kids out onto the street where they walked around until they saw, through their sunglasses, an example of one-point perspective. They looked funny crouching down along the sidewalk as they screeched out, “Hey look, the palm trees line up, and the parking meters meet up with them down the street!” The mentor taught a visual lesson but also learned a life lesson about the joy of seeing something new even in the context of the familiar. That kind of joy can do more for a frustrated artist than anything else in the world. It renews faith in the world and in the purpose of the medium.

One other question that I like to ask of my clients in order to bring out their personal definition of their passion is, “What would you create with your art if you won the lottery?” The reason for the question is obvious. A great obstacle to exercising our passion is the obligations, mostly financial, that make following our heart unsustainable. But if we were not encumbered with money issues, what would we create? I don’t know of anyone who has not thought about what they would do if they won the lottery. We have all probably considered how our lives would change if we hit the big one. So if you could create anything, and didn’t have to worry about money, what would it be? A gallery showing of your latest portraiture; a visual history of your hometown; a tabletop book of your trip to an exotic island? All of these projects could be financed with some introspection, a vision, a few connections, and some planning—and you would not have to win the lottery to do that.

Now here comes the fun part. Find the biggest surface you can write on. Maybe it’s an old piece of foam core, or a blackboard, or dry-erase board, or mirror, or sliding glass door—the biggest, least confining surface you can scribble on and not worry about cleaning off later. Now tape, thumb tack, or rewrite the results you developed on the timeline of your work history, the timeline of your personal experiences, the list of your skills, and the list of your interests. Get it out there big as life, because it is about your life. Arrange it any way you want, but put it out there where you can stand back and get a good long look at it.

What do your career and personal timelines tell you about what needs to be addressed first before you can make a career transition? Personal relationships (marriage, family, and friends), health matters (illness or accidents), economic factors, and other aspects of life all have an enormous impact, and it is useful to see how they are perceived and interwoven with your work timeline.

The beauty of this exercise is in the thought processes we bring to it, how we describe our reminiscences, and how we evaluate what we have accomplished. What are the lessons we can learn from putting it all in one place, so that we can look at it as objectively as we can? Do we observe ourselves as victims or masters of our fate? Will Rogers once said, “If you find yourself in a hole, stop digging.” Do we see ourselves as shadows of what we wanted to be, or as apparitions of our aspirations? Some of us see changes as the clash of infuriatingly hard choices, while others see change as a flowing river that one just blithely rides upon.

The truth is that life is a mixture of our fanciful expectations and our realized aspirations. The truth lies not in the extremes but somewhere in between. I always laugh when a new talent is described as “an overnight success,” because there were probably years of hard work and sacrifice that preceded that so-called overnight success. This, however, is often overlooked in the bright lights of instant fame. In a classic quote, Albert Einstein once wrote to a colleague, “I do know that kind fate allowed me to find a couple of nice ideas after many years of feverish labor.”

As you create your timeline in earnest, this dominating question emerges, have you been using the development of your passion as a major determining factor in making your life decisions? If you have been, then you will find it easier in the future to make the transitions that will keep you contributing and productive. If you have not, then you will find hollow satisfaction in other endeavors. Tough but true.

Obviously what we have just done is to match up your perception of your passion with the realities of living. This has been a short feasibility study to see if you are ready and able to move on to another level of expression. And one thing has become abundantly clear for the person who chooses a life in which creativity plays a major role: your passion has to be continuously monitored; it has to be discovered again and again and again, ad infinitum.

Now that you have it all in front of you, what do you see? What emerges from these fragments when they are woven together? My guess is that there is a tapestry more intricate than you anticipated. Is there too much information, or too many circumstances that make the image hard to comprehend? Then maybe you have to find a way to make it all simpler. Is there a hole where something meaningful should be? Then maybe you have to bring together the elements around the hole and mend the emptiness. What continuously got in the way of your growth as an artist? What did you allow to distract you from pursuing your abilities and possibilities? Are those things, those habits, those excuses still playing a role in your life? Have you been treating your passion as a hobby, or is it time to take it more seriously and raise it to the next level? If it is a passion, you will find the time.

Once you recognize that there is a problem, and you accept the reality that you must do something about it, the next stage in the creative process is logical. You have to determine what you have going for yourself, and you have to get your assets together in a focused way. You have to honestly reacquaint yourself with your strengths and your weaknesses, and address how you will use that knowledge to achieve your goals. Do you have what it takes to be competitive in the new marketplace? How do you capitalize on your skill sets and apply them to the new technologies? Next we will take a look at various ways others have taken their passion and enhanced their knowledge, so they could devote their time to what they desired most: visually capturing the moment.