Near the crystal-blue waters of the Mediterranean, in the village of Sarona, Israel, stood an old stone house with a red tile roof. It looked like any other house in the Tel Aviv historic quarter, and none of the people who passed its door gave the place a second thought. Nor did they notice the spark plug of a man who came and went from it throughout the day.

At 5 feet 2, with jug ears and slate-blue eyes, he sometimes wore a neat, inexpensive suit, sometimes his shirt open to his thick chest. If anyone overheard him speaking — which would happen only if he wanted to be heard — they would hear short, sharp machine-gun bursts of Hebrew spoken with a slight Eastern European accent. He walked with a lively step and a straight back, looking like he always had a place to go. Israel was a young country populated by many people with a strong sense of purpose, and he was one of them.

The man was Isser Harel, Chief of the Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations, better known as the Mossad, Israel’s secret intelligence agency. The old stone house was the organization’s headquarters.

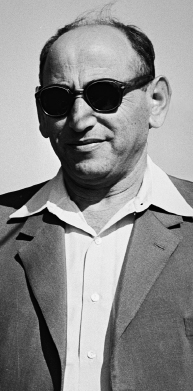

Spymaster Isser Harel in 1965.

Harel was the youngest son of Orthodox Jews from Vitebsk, in central Russia. The family’s prosperous business was seized after the 1917 Russian Revolution, and they moved to Latvia, where a young Isser survived his harsh new surroundings on the strength of his fists, a sphinxlike calm, and an omnivorous reading habit — everything from Russian classics to detective stories to Zionist literature. At sixteen, he decided to emigrate to Palestine. He obtained forged identity papers and traveled to Jaffa, the ancient port city at the southern end of Tel Aviv, with a small gun and a pocketful of bullets. When British officials searched the ship’s passengers for weapons, Harel easily passed inspection, his revolver and ammunition hidden in a hollowed-out loaf of bread.

In 1942, fearing that Hitler might attack Palestine, Harel enlisted in the Haganah, a Jewish paramilitary organization. He was recruited to its intelligence service, the Shai. They ran a network of informants and spies, stole records, tapped phones, decoded messages, and built up weapons caches. Though not as educated or cultured as many Shai agents, Harel quickly took to the trade. He soon learned to read, interpret, and remember the most important details of an operational file, and he earned a reputation as a bloodhound, capable of tireless work digging up the smallest details. In 1947, he was promoted to run Shai operations in Tel Aviv, where he developed an extensive network of Arab informants.

On the eve of May 14, 1948, as David Ben-Gurion prepared to announce the creation of an independent Jewish state, Harel personally carried a message to him from an informant: “Abdullah is going to war — that’s certain. The tanks are ready to go. The Arab Legion will attack tomorrow.” Ben-Gurion sent several Israeli army units to establish a defense against the forces of King Abdullah I of Jordan, thwarting their surprise attack. Harel had earned the leader’s attention.

Two months later, while Israel was still in the midst of war with Arab forces on all sides, Harel joined the other four section heads at Shai headquarters to reorganize Israeli intelligence and espionage operations. He was selected to run the Shin Bet, the internal security service (similar to the American FBI). The Arab forces withdrew in 1949, setting the legal boundaries of Israel where they are today. In 1952, Harel took over the Mossad.

Now, on a late September day in 1957, Harel had a rushed meeting at a nearby café with the Israeli Foreign Minister. The minister had urgent news from Germany that he did not want to share over the telephone: “Adolf Eichmann is alive, and his address in Argentina is known.”

When he got back to his office, Harel tasked his secretary to retrieve whatever files they had on Eichmann. He had heard that the Nazi had played a leading role in the Holocaust and that there had been many rumors as to his whereabouts over the years. But that was all he knew.

The Mossad’s lack of activity in pursuing war criminals reflected a lack of interest within Israeli society in general. Holocaust survivors, roughly a quarter of the population, rarely spoke of their experiences, both because it was too painful and because they did not want to focus on the past. They had a country to build.

Harel himself was haunted by what the Nazis had done to the Jewish people. The state of Israel existed in part to make sure that the Holocaust was never repeated. But he had never delved too deeply into the history of the genocide. His eighteen-hour working days were otherwise occupied.

Now he sat in silence with the Eichmann dossier his secretary had brought him. He read transcripts from the Nuremberg trials of high-ranking Nazis, SS files, testimony from Eichmann’s staff members, and numerous reports of Eichmann’s whereabouts.

Harel was completely unnerved by the portrait he formed. It was clear to him that Eichmann must be an expert in intelligence methods: He had managed to elude his pursuers for years. If they were going to bring this man to the justice he deserved, Harel knew one thing: They would need much more than an extradition request to the proper authorities in Argentina.

The first step was to see if the information that the Foreign Minister had given Harel in the café checked out. Harel wanted to know more about the minister’s German contact, Fritz Bauer, and whether he was a reliable individual with whom to work. He decided to send one of his agents to Frankfurt to meet with him.

Pleased at the rapid Israeli response, Bauer explained that his source, whom he did not name, had given him facts about Eichmann that matched known details of his life, particularly regarding his family. The source had also provided an address where the family was living with a man of the same age as Eichmann. Bauer was willing to do whatever it took to get to Eichmann — even to risk his position as attorney general — and Harel concluded that his tip was solid.

In January 1958, he sent another operative, Yoel Goren, to the address Bauer had given him: 4261 Chacabuco Street in Olivos, Buenos Aires. Goren had spent several years in South America and spoke fluent Spanish. Harel warned him to be cautious, fearing that the slightest error might cause Eichmann to run again.

Over the course of a week, Goren went to Olivos several times. Chacabuco Street was an untrafficked, unpaved road, and strangers were eyed suspiciously. This made surveillance a challenge, but what Goren saw convinced him that there was little chance Adolf Eichmann lived there. The house was more suited to a single unskilled laborer than the family of a man who had once held a prominent position in the Third Reich. Adolf Eichmann was supposed to have extorted the fortunes of Europe’s greatest Jewish families, not to mention the more limited wealth of many thousands of others. It seemed unlikely he could have been reduced to such poor quarters, even in hiding.

After taking several pictures of the house, Goren returned to Tel Aviv and reported to Harel that he had not seen anyone resembling Eichmann’s description enter or leave while the house was under his surveillance. In his estimation, Adolf Eichmann could not possibly live in that “wretched little house” on Chacabuco Street.

Harel was now skeptical about Bauer’s source and insisted on knowing his identity before getting more involved. Bauer agreed to write to Lothar Hermann to set up a meeting. When this was arranged, Harel sent the head of criminal investigations from the Tel Aviv police, Ephraim Hofstetter, to meet with Hermann.

Harel had tremendous faith in Hofstetter, a sober professional with twenty years of police experience. Polish by birth, Hofstetter had lost his parents and sister to the Holocaust. He spoke German fluently and could easily pretend to be working for Bauer — an important consideration, as Harel did not want the Eichmann investigation to be connected to Israel in any way. He told Hofstetter to find out how exactly Hermann knew about Eichmann, whether he was reliable, and whether he was holding anything back. He also asked him to identify the residents at 4261 Chacabuco.

Hofstetter arrived in Buenos Aires at the end of February, wearing winter clothes, only to discover that it was in fact the height of Argentina’s summer. He was greeted outside the airport terminal by the laughter of a pale man with a bald pink head: Ephraim Ilani.

Ilani was a Mossad agent who had taken a leave of absence to study the history of Jewish settlements in Argentina. Fluent in Spanish (as well as nine other languages), Ilani knew the country well and had a wide network of friends and contacts in Buenos Aires thanks to his easy humor and gregarious nature. Harel had asked him to work closely with Hofstetter, who spoke only a few words of Spanish.

The two journeyed by overnight train to Coronel Suárez. The following morning, they stepped onto the platform of a dilapidated station. Apart from a single road bordered on either side by wooden houses, the remote town was little more than a stopping-off point before the endless grasslands of the Pampas. It was hard to imagine a less obvious place for a clue to Adolf Eichmann’s whereabouts.

After some inquiries, they got directions to Lothar Hermann’s house. Hofstetter went to the door alone, Ilani staying behind in case there was any trouble. Several moments after Hofstetter knocked, the door opened. Hofstetter introduced himself to Hermann. “My name is Karl Huppert. I sent you a telegram from Buenos Aires to tell you I was coming.”

Hermann indicated for Hofstetter to come into his living room. The Israeli policeman could not place what was wrong with Hermann or with the room, but something was amiss. Only when Hofstetter held out his letter of introduction and Hermann made no move to take it did he realize that the man was blind.

He couldn’t believe it. Isser Harel had sent him to check on a sighting of Adolf Eichmann by a man who could not see.

He lost his skepticism, however, when Lothar Hermann and his wife, who came into the room to read the letter, explained in detail how they had first grown suspicious of Nick Eichmann and how their daughter had tracked down his address.

“Don’t think I started this Eichmann business through any desire to serve Germany,” Hermann said. “My only purpose is to even the score with the Nazi criminals who caused me and my family so much agony.”

The front door opened, and Sylvia came in, calling out hello to her parents. She stopped on seeing Hofstetter, and her father introduced “Mr. Huppert.” Sylvia confidently told him about her visit to the Eichmann house.

“Was there anything special about the way he spoke?” Hofstetter asked her.

“His voice was unpleasant and strident, just as Dr. Bauer described it in one of his letters.”

Hofstetter asked her if these letters might have steered her wrongly to think the man at the house was Eichmann.

“No,” she said bluntly. “I’m one hundred percent sure it was an unbiased impression.”

“What you say is pretty convincing,” Hofstetter said, impressed by her straightforwardness, not to mention her courage in going to the Eichmann house alone. Everything she said matched the information he had been given in Tel Aviv. “But it isn’t conclusive identification. Vera Eichmann may have married again — we’ve heard many such rumors — and her children may have continued using their father’s name.” He explained that he needed to know the name of the person living with Vera and her sons, as well as where he worked. He also wanted to get any photographs of him or his family, any documents with his name, and, in the best case, a set of his fingerprints.

“I’m certain I’ll be able to get you your proof,” Hermann said. “I’ve got many friends in Olivos, as well as connections with the local authorities. It won’t be difficult for me to get these things. However, it’s obvious I’ll have to travel to Buenos Aires again, my daughter too … This will involve further expense, and we simply can’t afford it.”

Hofstetter reassured Hermann that his people would cover any expenses. He instructed that all their correspondence be sent to him at an address in the Bronx, New York, care of an A. S. Richter. He tore an Argentine dollar in two and gave one half to Hermann. Anybody with the other half could be trusted.

After two hours of planning and discussion, Hofstetter thanked the family and left. He reported back to Harel that the Hermanns were reliable but that more information was needed and that they seemed capable of gathering it.

On April 8, 1958, Sylvia and her father visited the land-records office in La Plata, the capital city of the province of Buenos Aires. A clerk brought them the public records on 4261 Chacabuco Street, and Sylvia read the details out to her father. An Austrian, Francisco Schmidt, had bought the small plot on August 14, 1947, to build two houses.

Eichmann was Austrian, Lothar knew. “Schmidt” must be the alias under which he was living. Excited by this discovery, Hermann and his daughter took a train to Buenos Aires to seek confirmation. Through a contact at the local electricity company, they found that two electric meters were registered at the address, under the names “Dagoto” and “Klement.” When Hermann located the people who had sold Schmidt the land, he was given a description that resembled the one Bauer had sent and that his daughter had confirmed on her brief visit to the house.

The following month, the Hermanns returned to the city for five days to continue their investigation. They discovered a photograph of Nick, but their attempts to get one of Eichmann, or his fingerprints or any identity documents, failed.

On May 19, Hermann wrote to “Karl Huppert” in New York, recounting their investigation of the past six weeks. “Francisco Schmidt is the man we want,” he stated confidently. Further investigation would require more funds, he continued, and he should “hold all the strings” in pursuing the matter. Hermann was convinced that his discoveries would be met with a call to action. His letter wound its way from Argentina to New York to Israel, arriving at the Mossad headquarters in Sarona in June 1958.

Isser Harel was skeptical about its contents from start to finish. Just because Schmidt was listed as the owner of the land where a Nick Eichmann lived did not prove that Adolf Eichmann inhabited the house, nor under that alias. Hermann’s demand for more funds and to “hold all the strings” stank of a potential scam. Hermann was too certain and wanted too much control — both factors Harel distrusted by instinct and experience. Harel trusted his intuition, and it told him that not only was Yoel Goren right in thinking that the former Nazi officer could not be living in the poverty he had witnessed, but also that the information Lothar Hermann had sent in his report was suspect at best and fantasy at worst.

Just to be sure, Harel cabled Ephraim Ilani in Buenos Aires to ask him to check on Francisco Schmidt. At the end of August, Ilani reported that Schmidt was not Eichmann, nor did he live at the Chacabuco Street address. He was merely the landlord. Hermann had the wrong man. Harel informed Bauer of his conclusions and ended all correspondence with Lothar Hermann.

The trail went cold once again.