Yosef Klein paced the apron beside the airport terminal, confused as to why the plane had stopped. He had checked and rechecked everything. There was no reason the plane should not have departed, unless its secret passenger was known. Klein tried to make eye contact with someone in the cockpit, but nobody was moving, nor did they open a window to call out to him. After what felt like an age, he saw one of the pilots gesture for stairs to be brought to the plane’s side. Then the doors opened, and Shaul stepped out.

Klein waited for him at the bottom of the steps. “What the hell is happening?”

“The tower wants something to do with the flight plan,” Shaul said.

Klein knew it was highly unusual for a plane to be stopped and the navigator summoned out. This might be a trap.

“Shall I go with you?” Klein asked.

“No, wait. I’ll do it alone.”

Shaul hurried to the tower. He climbed the stairs slowly, like a man approaching the gallows.

“What is the problem?” he asked the controller in English, looking around for any sign of the police.

“There’s a signature missing,” the controller said, holding the flight plan up in his hand. “And what is your alternate route?”

Shaul relaxed. “Porto Alegre,” he replied before adding the detail to the plan and signing the document. Then he rushed back down the steps. “Everything’s okay. Something was missing on the flight plan,” he said to Klein as he passed him.

In the cockpit, everybody sighed with relief when Shaul reported what had happened. The doors closed again, and Tohar called the tower. “This is El Al. May we proceed?”

“Affirmative.”

At 12:05 A.M. on May 21, the plane rushed down the runway and lifted off. Once they had crossed out of Argentine airspace, excitement swept through the cabin. The “El Al crew” in first class rose from their seats, hugged one another, and cheered their success. Wedeles and the few other true crew members who already knew the special passenger’s identity joined in the celebrations. The spontaneous outburst surprised Harel, and although he had hesitated to inform everyone else on the flight of the circumstances, it was clear now that secrecy was pointless.

Harel allowed Adi Peleg, the El Al security chief, to deliver the news: “You’ve been accorded a great privilege. You are taking part in an operation of supreme importance to the Jewish people. The man with us on the plane is Adolf Eichmann.”

A shock wave of emotion followed his words. The flight attendant sitting next to Eichmann felt her heart sink. She stared in disbelief at this skinny, helpless man, nervously drawing on a cigarette, his Adam’s apple bobbing up and down in fright. In disgust, she stood up and moved away.

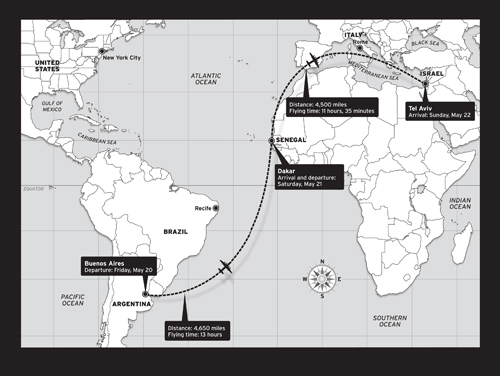

In the cockpit, it was all business. The plane gained altitude, and Tohar steered due northeast across Uruguay and out over the Atlantic, following the course that Shaul had plotted to give them the best chance of reaching Dakar.

There were no computers or calculators at this point in aviation history, so navigation depended on charts, pencils, compasses, dividers, rulers, and lots of math. Once over the ocean, the flight engineer and the navigator figured out their position using the stars and a sextant that projected through a hatch in the flight-deck ceiling. A large almanac held details of the stars’ positions throughout the year (and the sun and Venus for navigating by day) and enabled them to calculate their position in the sky every forty minutes. Once the calculations were complete, they were then rechecked by the other engineer and navigator. The calculations for each star shot meant they only had about five minutes’ break before starting the process again.

Zvi Tohar, both of the navigators, and flight engineer Shimon Blanc had supervised the Britannia’s proving flight between New York and Tel Aviv in late 1957. That journey had covered 5,760 miles in fifteen hours — the longest flight ever taken by a commercial airliner at that time — in a plane stripped of its seats, its galleys, and anything else deemed unnecessary, including passengers. The lack of weight meant that their fuel went a lot further. They had also had the benefit of a strong tailwind of roughly sixty-five miles per hour. For that flight, they figured the maximum still-air (no wind) range of the plane to be around 4,700 miles. The distance from Buenos Aires to Dakar was 4,650 miles. While they could expect some tailwinds along the route, they were still carrying some four tons of additional weight, and this meant they had to fly 2,000 to 3,000 feet lower than on the proving flight, consuming roughly 5 percent more fuel per hour. There was no guarantee that the wind conditions would be to their advantage.

Shaul and Tohar were confident that they would reach Dakar, but they were also conscious that anything might happen to interfere with their plans. Over a thirteen- to fourteen-hour flight, slight deviations could add up to create big problems. At best they might be able to divert to another African airport — perhaps Abidjan in the Ivory Coast. At worst, they might run out of fuel over the Atlantic.

At half past midnight, Nick Eichmann learned from someone in his search party that an Israeli passenger plane had departed Buenos Aires for Recife. Nick was certain that his father was on board. With the help of a former SS man, he alerted a contact in the Brazilian secret service and asked him to intercept the plane when it landed in Recife — exactly the threat that the nonstop flight to Dakar aimed to counter.

Hour after hour passed as the El Al plane crossed the wide expanse of the Atlantic. It flew first toward the volcanic island of Trinidad, 680 miles east of Brazil, then north toward Dakar. Periodically, the radio operators listened in for new weather forecasts, the navigators made slight alterations in their route, and Harel popped his head into the cockpit to ask if everything was on track.

In his seat in the back of the plane, Adolf Eichmann continued to be as compliant as he had been in the safe house. The doctor had stopped giving him the sedative once they had boarded the plane, and he was still handcuffed and goggled, but Harel ordered Eichmann’s guards to stay ready, fearing that he might attempt to kill himself. The prisoner smoked heavily and fidgeted constantly in his seat. Now that they were in flight, most of the crew kept their distance from him.

The morning after the Britannia departed, Yosef Klein wrapped up his El Al business in Buenos Aires and boarded a flight back to New York. There was no time for the sightseeing trip in Brazil he had planned on his journey out. His reward had been to see the taillights of the plane disappear into the night with Adolf Eichmann on board.

That same morning, Rafi Eitan, Peter Malkin, Avraham Shalom, and Shalom Dani woke up at Tira, relaxed for the first time in months. Their mission had gone well, and Eichmann was no longer their responsibility. Still, there were a few loose ends to tie up: They erased all trace of their presence in the various safe houses, burned or disposed of any material they did not plan on taking with them, and returned the last of their cars. The final task on the list was to get out of the country.

Dani was booked on a flight out of Argentina the next day, but, with the anniversary celebrations in full flow, there had been no flights available for Eitan, Malkin, or Shalom. They bought three tickets for an overnight train to Mendoza, on the Chilean border. From there they would take another train through the Andes to Santiago. Isser Harel had assured them that the announcement of Eichmann’s capture would not be made until they were all safely back in Israel.

In the Britannia cockpit, red lights blinked furiously as the plane descended over the Atlantic toward Dakar. They had flown for close to thirteen hours and far beyond the 4,650 miles projected. Shaul had altered their flight path and altitude a number of times during their ocean crossing to find more favorable winds. Once, Tohar jokingly went through the cabin asking if anybody had a cigarette lighter because they needed all the fuel they could get.

Now the time for jokes had passed. The gauges flashed that the plane was dangerously low on fuel. If there was a problem in Dakar, if the runways were shut down for any reason, they would not have enough gas to fly around the airport while waiting for permission to land or to divert elsewhere. The cockpit was silent, everyone focused on the task at hand. Tohar stared out the window, focused on the horizon.

Finally, he saw Dakar through the window. He lowered the landing wheels and decreased their altitude. A final few breathless moments passed before they made a smooth landing on the runway, thirteen hours and ten minutes after leaving Buenos Aires. Tohar shut down two of the engines as soon as he slowed the plane, unsure whether there was sufficient fuel even to taxi to the terminal.

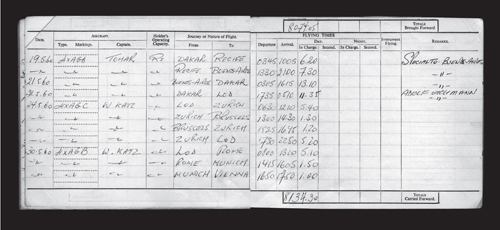

The navigator’s logbook for the El Al flight.

Isser Harel congratulated the cockpit crew, but he was worried that the Argentine authorities might have contacted Dakar during their flight, warning them that they might be carrying a suspicious passenger. If this was the case, a thorough search of the plane could be expected. Elian injected Eichmann with more sedative, and Gat sat down next to him. A steward drew the curtain across the first-class cabin and turned off the lights.

While an airport services crew refueled the plane, two Senegalese health inspectors came on board. Gat heard someone speaking in French. He placed Eichmann’s head on his shoulder and pretended to be asleep. The inspectors barely gave the cabin a second look.

The rest of the stopover went smoothly. The crew loaded more food, and Shaul and Hassin filed a flight plan to Rome, even though they were going straight to Tel Aviv. They had already plotted out a 4,500-mile, eleven-hour route. They knew that the tailwinds over the Mediterranean were much stronger than those in the South Atlantic, meaning that the journey would not test the plane’s limits in quite the same way as the journey to Dakar had done.

One hour and twenty minutes after landing, they left Senegal. The plane flew up the west coast of Africa, then northeast to Spain, gathering speed from the tailwinds as it turned almost due east toward Italy.

The flight deck told air-traffic control in Rome that they would be heading on to Athens. They then flew southeast across the Mediterranean before announcing to the Athens air-traffic controllers that they would go straight to Tel Aviv. They crossed southern Greece, skirting Turkey, then shifted toward Israel.

When the plane was making its final approach toward Lod Airport near Tel Aviv, Harel washed his face, shaved, and put on clean clothes, preparing himself for the rush of activity that would greet his arrival. He informed his men of their duties on landing, then stared out the window, eager to see the Israeli coastline appear out of the early morning sky.