Early on Sunday, May 22, Zvi Tohar lowered the landing gear on the plane. Fifteen minutes later, the wheels touched Israeli ground. There was no celebration as there had been when leaving Buenos Aires. The crew had been flying for almost twenty-four hours straight, and the agents watching Eichmann had not rested either. The mood in the aircraft was one of simple relief.

Tohar taxied to the terminal, where most of the crew disembarked. Harel made sure to shake everyone’s hand as they left the plane. The captain also warmly thanked each of them as they stepped out. Then the doors were closed again, and Tohar taxied to the El Al service hangars, far from the terminal.

The moment they arrived, Harel left the plane and strode into one of the hangars, where he found a grease-smudged phone to ring Shin Bet headquarters. “The monster is in shackles,” he told one of his lieutenants, then he ordered a vehicle. A short while later, a windowless black van appeared alongside the plane.

Tabor and Gat escorted a trembling, blindfolded Eichmann down the steps and into the back of the van. Harel explained to Gat that he was to take Eichmann to the secret Shin Bet detention center, which was located in an old Arab house on the edge of Jaffa. He then hurried toward Jerusalem, hoping to see David Ben-Gurion before his 10 A.M. cabinet meeting.

A secretary led him into the Prime Minister’s office.

“I brought you a present,” Harel said.

Ben-Gurion looked up from his paper-strewn desk, surprised to see him.

“I have brought Adolf Eichmann with me. For two hours now he has been on Israeli soil, and, if you authorize it, he will be handed over to the Israeli police.”

Ben-Gurion remained silent for a few moments. “Are you positive it is Eichmann?”

It was not the response Harel expected, and he was slightly taken aback. “Of course I am positive. He even admitted it himself.”

“Did anyone who met him in the past identify him?”

“No,” Harel said.

“If that’s the case, you have to find someone who knew him to go and inspect Eichmann in jail. Only after he has been officially identified will I be satisfied that this is the man.”

Harel understood Ben-Gurion’s caution, knowing the implications of any announcement he made. Even so, there was not a shred of doubt in his own mind that they had their man.

A few hours later, Moshe Agami, who had been a Jewish Agency representative during the war, was brought to Eichmann’s cell. Agami had met Eichmann at the Palais Rothschild in Vienna in 1938, when the Nazi had made him stand to attention in his office while he pleaded for permission for the Jews to emigrate to Palestine. Agami confirmed Eichmann’s identity. After he left, Benno Cohen, the former chairman of a Zionist organization in Germany in the mid-1930s, also identified the prisoner as Eichmann.

Harel phoned the Prime Minister and delivered the news. At last Ben-Gurion allowed himself to relish the operation’s success. He wanted to announce the capture the next day. Harel asked him to wait — some of his agents were still in South America.

“How many people know Eichmann is in Israel?” Ben-Gurion asked.

Already more than fifty, Harel admitted.

“In that case, no waiting. We’re going to announce!”

Early the next morning, May 23 — a blisteringly hot, cloudless Israeli day — Adolf Eichmann was brought in front of Judge Emanuel Halevi in Jaffa. When asked for his identity, he answered without hesitation, “I am Adolf Eichmann.”

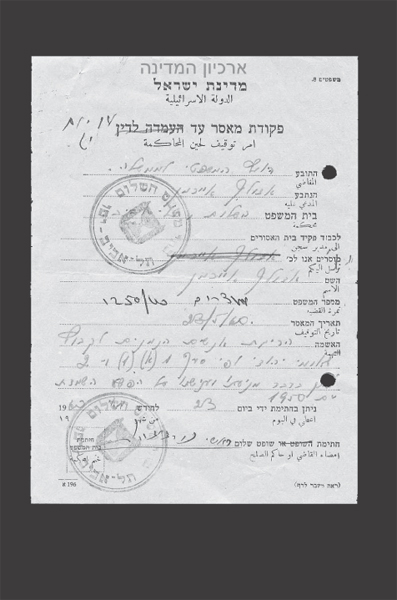

His voice cracking, Halevi charged him with the crime of genocide and issued his official arrest warrant.

Eichmann’s detention warrant.

In a restaurant in the center of Cologne, Fritz Bauer was waiting for an Israeli associate of Harel’s, who had called an urgent meeting but who was now late. Bauer suspected something had gone terribly wrong with the Eichmann mission.

Harel’s associate came into the restaurant and crossed quickly to the table. When Bauer heard the news of the capture, he leapt from his seat, tears welling in his eyes, and kissed the Israeli on both cheeks. Isser Harel had thought that the Hesse attorney general deserved to be told of the mission’s success before it hit the headlines.

Now it was time for the rest of the world to know. At 4:00 P.M., David Ben-Gurion strode into the Knesset, Israel’s parliament. Some had heard he had a special announcement, but no one had any idea what it might be. He stood at the podium, and the chamber hushed. In a solemn, strong voice he said, “I have to inform the Knesset that a short time ago one of the most notorious Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann — who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called the ‘Final Solution of the Jewish Question,’ that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe — was discovered by the Israeli security services. Adolf Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their helpers.”

For a moment, everybody was rooted to their seats, unsure whether they had heard the Prime Minister correctly or that what he said was true. Slowly, they realized the enormity of his statement, and it was as if the air had been knocked from their chests.

“When they had recovered from the staggering blow,” an Israeli journalist later reported, “a wave of agitation engulfed the hearers, agitation so deep that its likes had never before been known in the Knesset.” Many went pale. One woman sobbed. Others jumped from their seats, needing to repeat aloud that Eichmann was in Israel in order to come to terms with the news. The parliamentary reporters ran to their booths.

Ben-Gurion stepped down and left the hall. Nobody was quite sure what to do as the chamber buzzed with the news. Eichmann. Captured. That was all anyone heard. Within hours, all of Israel and the rest of the world would be equally astonished by the historic announcement.

A Holocaust survivor displays her Auschwitz tattoo as news of Eichmann’s arrest breaks. The capture and trial would be a transformative moment for survivors to speak of what they experienced at the hands of the Nazis.

On May 25, Avraham Shalom was on a bus back to his hotel in Santiago, Chile. He had only just been able to send a cable to Mossad headquarters, notifying Isser Harel that he, Eitan, and Malkin were safe. They had arrived in the country three days earlier, after a breathtakingly beautiful journey by steam train from Mendoza through the Andes. On the day of their arrival, southern Chile had suffered a devastating earthquake, the most powerful ever recorded in the world, which had killed thousands and sent tsunamis surging across the Pacific.

Shalom looked idly over the shoulder of a passenger ahead of him, who was thumbing through a newspaper. There, in bold letters, he saw the word EICHMANN. Stunned, he stumbled off the bus at the next stop. At a corner stand, he bought a whole bundle of papers, most carrying the headline BEN-GURION ANNOUNCES THE CAPTURE OF ADOLF EICHMANN.

Shalom was livid. Nobody was supposed to know about the operation until they were all back in Israel. When he showed Eitan and Malkin the newspapers, they were equally angry, but there was nothing they could do about it. A few days later, they secured flights out of Chile. By chance, Shalom and Malkin were both routed through Buenos Aires, and they spent a worried hour on the tarmac at Ezeiza before takeoff.

At last they arrived home. Shalom discovered that his wife already knew he had been on the mission. Yaakov Gat had visited several days before to assure her that her husband was all right and would soon be home. Shalom knew that she would never utter a word about his involvement.

The others had similar experiences. On the evening of Ben-Gurion’s announcement, Moshe Tabor was at the cinema with his wife when the film was interrupted by the news. Turning to him, she said, “You were in India, I thought?” Tabor tried to distract her, but she told him that she had noticed the toy pistol he brought home for their son was stamped MADE IN ARGENTINA.

At Peter Malkin’s first family Sabbath dinner after his return, his brother talked of nothing else, wanting to know what had happened while Peter was in “Paris” for the past month. Malkin pleaded ignorance. His mother pushed him to say where he had really been.

“Look, didn’t you get my letters?” he asked.

“They were like all your letters. They could have been written last year or tomorrow…. Were you involved with this?”

Malkin desperately wanted to tell her that he had been involved and that he had avenged his sister Fruma’s death. “Please, Mama … Enough. I was in Paris.”

Zvi Aharoni made the same excuse when his brother called him unexpectedly, wanting to know when he had returned to Israel. “I’m not naive,” his brother said. “I know you were away for over two months, and I heard Ben-Gurion on the radio. I can add two and two together. Or can I? Well done!”

A Shin Bet secretary, who had also tied Aharoni’s absence to the news, threw her arms around him on his first day back in the office. No words were needed.