“We certainly did have a nice sleep,” I reported to Joe Allen shortly after we woke for the third day of the mission. “The moon is getting bigger out the window.” I could see small details with my naked eye, such as little craters I had never glimpsed before without a telescope. The moon was bright and not quite half full. Dave and Jim needed to arrive at their landing site while the sun was still low. Any higher and it would be too hot for their surface equipment to function safely.

The three of us now looked a little scuzzy. None of us had shaved, and we wouldn’t for the entire flight. We were explorers. Have you ever seen a picture of an explorer without a long, straggly beard? We planned to embody that adventurous spirit.

We also decided not to wash. That was fine, because we didn’t need to. We were in the cleanest environment possible—a spacecraft assembled in a spotless room. Our air-conditioning system scrubbed out most of the odors. Jim had brought along a bar of soap, but not for washing. We put the soap inside a wet rag and whirled it around to make the cabin smell nicer.

I did, however, brush my teeth. Plus, of course, we all had to pee and take a crap. Just because we were away from Earth, that urge didn’t change. However, we had a challenge—in space, everything floats.

Peeing was relatively easy. The urine collection device was shaped like a condom, connected to a tube that fed into a plastic bag. Opening a valve, I could flush my urine out into the vacuum of space, where it froze into thousands of crystal flakes. I preferred to perform a urine dump right before we fired our engine. Otherwise, without any other gravitational attraction, the snowflakes surrounded our spacecraft in a large cloud. If I tried to sight stars though the navigational system, I might aim at my own urine and think it was a star. Firing our engine moved us away from the cloud, which, for all I know, is still out there, our personal contribution to the solar system.

Taking a crap was more primitive. We used plastic bags with a six-inch opening, surrounded by a circle of sticky tape. We’d roll down our long johns, slap the bag on and go. Then we’d wipe ourselves and throw in the used tissue, seal the bag, knead germ-killing liquid into the whole mess, and roll the bag into the smallest possible shape. We’d write our name and the flight time on it and float it to a container that held all these gift-wrapped goodies. Later, some lucky doctor back on Earth would get to work through them all.

Three of us shared this tiny space, so there was no privacy. On an earlier moon flight, one crewmember had tried to hold it in for six days and got pretty sick. It wasn’t pleasant to have someone float inches from your face with a bag stuck to his butt. That fragrant bar of soap was a welcome antidote. But we were grungy explorers and we didn’t let it bother us or give it a second thought.

Back to business. Mission control asked Dave and Jim to carefully vacuum the surfaces inside Falcon where glass may have stuck, and then leave the vacuum cleaner running in there to catch any additional floating shards.

Before that, we carried out an unusual experiment. Each of us had seen bright flashes when our eyes were closed, and so had crews before us. Scientists believed these flashes were cosmic rays whizzing through space and passing through our heads. We placed the shades in the windows, put on eyeshades, and reported how many flashes we saw in an hour—and there were many. The effect was like flashbulbs going off across a crowded sports stadium as these high-energy particles zapped through our skulls. We reported the many directions the streaks of light seemed to be coming from. Were they striking our retinas or hitting a deep part of our brain, activating our visual senses there? We didn’t know.

We were close to the end of our day’s tasks when Dave announced to Houston that we had another problem. Down in the equipment bay, Jim spotted the outlet for our water supply leaking right around the cap. In weightlessness, a wobbling ball of fluid grew around the leak, while water also slowly crept across the surrounding surfaces. This was not good. Had a pipe broken? Would we be able to stop the leak?

Karl Henize asked a question from the ground. “Can you give us an estimate of how many drips per second?”

Jeez, Karl, I thought, we’re in space. Water doesn’t drip in weightlessness. But we worked through this brief confusion. NASA engineers and contractors around the country began to look for a solution.

“It’s accumulating at a pretty good rate,” Jim informed Karl with a slight note of alarm. If this water floated into our electrical systems, there would be hell to pay. Following instructions from the ground, we begin to turn off pressure regulators and tank inlets, hoping to stop the leak. We also began to soak up the growing water sphere with towels.

Within fifteen minutes, Houston radioed a solution. I later heard they tracked down a technician who was on his way home, and he knew exactly what to do. We pulled out the tool kit, tightened the fitting, and the leak stopped. If it hadn’t, we would not have landed on the moon. It made me think, as I floated there, why it was important to send people into space. A robotic spacecraft couldn’t fix itself.

“Nice to have the quick response … we about had a small flood up here,” Dave radioed with relief. It was teamwork at its finest. Mission control later told us that Captain Cook’s Endeavour had also sprung a leak on one of its voyages, which made us feel even more like grizzled explorers. “You guys didn’t strike a coral reef there, did you?” they joked with us. “Sounds to me like the Endeavour has a few plumbers aboard.”

The plumbing work had made me thirsty. Surrounded by wet towels, I decided to make a hot coffee. I had three kinds made up for me on the flight: black, black with sugar, and black with cream and sugar. If I couldn’t have a slug of the Oso Negro vodka I’d hoped to sneak aboard, a jolt of black coffee would be the next best thing.

Instead of coffee, Jim and Dave had loaded up their drink menus with hot chocolate. I’d warned against it. Sweet and sticky, it was sickly, nasty stuff for a spaceflight. Interestingly enough, I hadn’t seen Dave or Jim drink much of it so far. And, looking at my meager coffee supply, I noticed the number of packages was going down awfully fast. I’d need to protect my supply before they drank it all.

Although there was no sense of it in the spacecraft, we’d slowed down from twenty-five thousand miles per hour when leaving Earth orbit to a relatively sluggish three thousand miles per hour. Earth continued to pull on us. But now the moon’s gravity tugged more strongly on us than Earth’s. As we fell toward the steadily growing moon, our speed began to pick up again.

We would reach the moon the next day. It was time to sleep. I felt so comfortable in space now that I didn’t bother with the sleeping bag. Instead I flattened out my couch, put a strap around me so I wouldn’t float into the instrument panel, and slept.

All too soon, it was morning. Time to put my spacesuit back on—just as a precaution. It was a lot easier putting it on in space. I simply let the suit drift in front of me and floated into it.

We prepared to jettison the door covering the SIM bay. Better to do it now, we reasoned, than in lunar orbit, in case it hit the large engine bell at the rear of the spacecraft. This operation was a first for the Apollo program, which is why we suited up. That door was a hunk of metal five feet wide and more than nine feet long, and we were going to release it with explosives.

After another quick course correction burn, we blew off the door. I felt a faint shudder through the spacecraft as the explosives fired and the panel slowly tumbled away. The detonation jolted a thruster valve closed, but we quickly reopened it from the control panel. My bay of prize experiments was now exposed to space, ready to whir into action when we reached lunar orbit.

“You’ll be interested to know that there’s a very thin crescent moon in front of us,” I told Houston. “It may be thin, but it’s big.”

The sunlit part of the moon had shrunk to a delicate sliver. And in the faint reflected light from the distant Earth, the rounded bulk of the shadowed side loomed at us as we approached. For the first time, I could see that the moon was truly three-dimensional. It was eerie.

Less than an hour before arrival we dropped into its shadow. Picking up speed, we fell toward the moon’s western edge as its dark mass grew in our windows. We turned the spacecraft so our main engine faced forward, ready to slow ourselves into lunar orbit. We’d make that engine burn behind the moon.

“Have a good burn,” Karl radioed as we prepared to lose our radio signal.

“We’ll see you on the other side,” Dave replied. Then we lost them.

We hurtled behind the moon for eight minutes, then lit our engine. It was a beautifully smooth and precise burn. For six long minutes we slowed down, gently pressed into our couches, curving our path so that we fell around the dark surface: not too close, not too far. “Looks like it’s running smooth … Holding steady,” I told Dave and Jim as I monitored the engine thrust. We were ready to intervene if the burn didn’t end at the correct moment. But it did. “Shutdown. Fantastic!” Dave announced. We were in lunar orbit.

Mission control, of course, had no idea that our burn had been successful. All they could do was wait for more than half an hour to pick up our signal as we rounded the moon’s eastern limb. If they acquired us early, that would mean our burn hadn’t been successful and we’d be hurled away from the moon, back toward Earth.

We curved around the moon’s far side, intensely studying our instruments. Then, out of the window, I saw what looked like a series of ghostly ocean waves coming toward me from the deep blackness. This was weird, and unexpected. What was I seeing?

The waves seemed to billow and grow as my confused mind tried to make sense of the glowing, shifting patterns. Then I slowly began to comprehend the sight. Sunlight was hitting the top of the tallest lunar mountains as we passed over them, and the peaks were separated by deep black shadows. As we continued to round the moon into sunlight, the shadows grew thinner, and I could begin to make out surface features.

Even after the years of training, I never expected the moon to look this eerie and dramatic. After days of falling through empty space, I was vividly aware of how close we were to this immense landscape. It felt scary to be grazing over mountains and valleys which now filled our windows with an ever-changing drama. I’d never understood the word “unearthly” before, until I was somewhere that was literally not this Earth. This place was different.

We rounded the far side in 34 minutes and reestablished contact with Earth. We’d reacquire and lose them every time we circled the moon. “Hello, Houston, the Endeavour’s on station with cargo, and what a fantastic sight,” Dave reported. “Oh, this is really profound, I’ll tell you—fantastic!” Dave’s fascination with geology was kicking in, and he was overwhelmed by the vistas below us.

The moon looked ancient, battered, pockmarked—and dead. I didn’t feel a sense of foreboding, but of lifelessness. Compared to our beautiful Earth, I didn’t feel there was anything here that would support humankind.

Our Saturn V third stage had trailed us all the way to the moon. Now, out of our view, it slammed into the lunar surface and gouged out a fresh crater. The shock from the impact sent an earthquake-like ripple across the moon, picked up by seismometers left by the Apollo 12 and 14 crews. Our first surface experiment was complete, and we’d literally changed the face of the moon.

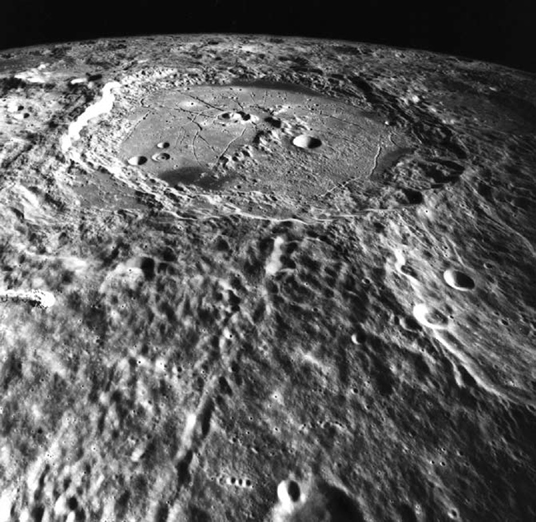

The magnificent lunar surface from orbit

Compared with prior missions that circled comfortably near the lunar equator, we were in a strange, complicated orbit. It took us much farther north into unseen territories, and Dave continued to report with both geological precision and wonder as we skimmed over regions no human eye had ever seen this close. He was in his element. Why choose between being a spacecraft pilot or an observational scientist? From our first moments in orbit, Dave showed that a good commander could do both.

With no atmosphere to soften the lunar features, they looked disturbingly close and sharp. It was the same moon I knew from photos in my training, but when it filled my window it looked strikingly different. Seeing a dark circle on a map is abstract, but skimming across that same five-hundred-mile-wide basin in person was real. The variety was fascinating: faults, swirls, wrinkles, powdery dustings, and features that looked weathered by Earth-like oceans and dust storms. Rivers of ancient lava rippled across the barren plains. I reported with excitement on subtle surface flows, patterns, and variations in colors and shades. “After the King’s training, it’s almost like I’ve been here before,” I remarked, using our nickname for Farouk.

The shadows lengthened again, until only mountain rims remained to catch the sunlight. We kept reporting until we sped into shadow once more. The ground radioed that Farouk had been listening in and was delighted with our descriptions so far. Then, once again, Earth slipped below the horizon and we were on our own.

We burned our engine once more, which dropped us into a lower orbit. “Man, it already looks like we’re lower,” Jim remarked, as lunar features zipped by. He was right—it felt as if we were diving toward the surface, and mountains ahead of us looked unnervingly higher than our flight path. The lowest point of our orbit was now less than eleven miles above the surface and coincided with passing over the planned landing site. Some of the mountains around that zone reached up fifteen thousand feet. I stayed very aware of our altitude as we slid around the moon, documenting the uncharted regions with photos and words. As we sailed toward the highest peaks, I almost felt like pulling my feet up.

Dave and Jim would land on the moon the next day. As we ate dinner, Jim was making plans. “I think the first thing I’m going to do when we get back,” he explained, “is a beautiful night in Tahiti.”

“Hey, you’re on, buddy, you’re on!” I replied. But I knew what he was really saying. Tomorrow would be a risky day for Jim. By planning ahead, he was telling me—and himself—that he would survive the mission. It was a good idea. But I momentarily thought of those old World War II movies, where the guy tells his colleagues how he is going to marry his sweetheart when he gets home. He always dies in the next reel.

Mission control woke us early the next day informing us that, while we slept, our orbit had dropped faster than predicted. Denser parts of the moon, called “mascons,” pulled harder on the spacecraft as we passed over them. Flying over unexplored regions, we found mascons the hard way. Taking the shades off the windows, I looked out with alarm as we passed an immense lunar mountain. It looked like the peak was above us. I could clearly see small boulders littering its side, although that might have been because my eyes were wide with alarm. How low were we? We were planning to land on the moon today—but not by hitting a mountain.

Mission control gave us the figures. We had dropped down under forty-six thousand feet. Phew, we were okay, still three times higher than the mountains around the landing site. I realized the spacecraft was tilted at an angle when I’d looked out the window, so the surface only appeared to be sloping above us. But boy, those boulders looked so close. I felt like I could reach out and touch one.

Another few hours, and that might have been true. Mission control calculated that we would drop even farther as the day went on, and their margin of error was getting too close to the top of those peaks. By the time we were over the landing site, we might be as low as twenty-four thousand feet and falling.

“You can see how, when you’re coming up at low altitude on these mountains, how striking they are in the distance,” I told mission control. “It’s really hard to miss them.”

“I hope you can miss them!” mission control joked in reply. But they had a serious point. We pulsed our thrusters and raised our orbit a little.

It was an extra task in a day that was already packed. Dave and Jim headed into Falcon as early as possible to prepare for their lunar landing and were soon busy ensuring there was no broken glass in their spacesuit hoses.

We were fast approaching a vital moment in the mission: our two spacecraft would undock. The ground informed us that Neil Armstrong was watching from the mission control viewing area, while lunar module hotshot Ed Mitchell took over as CapCom. Ed began reading and confirming precise data sequences to us. We floated back into our spacesuits, updated the lunar module’s guidance computer, tracked landmarks, and equalized spacecraft pressures. The computers in both spacecraft were too primitive to talk to each other, so we had to manually enter information so that they agreed on where we were and how fast we were orbiting. Dave raced ahead on the timeline, keen to get everything prepared. It took hours and drew on some of our toughest engineering training.

It was time to lock the hatches between the spacecraft. We were so engrossed in our work that there was never a moment to pause and say good-bye and good luck. I guess we didn’t need to. Dave and Jim relied on me to keep Endeavour, our only ride home, in lunar orbit for them. I had confidence they would survive their ambitious lunar surface explorations.

I hit the switch to separate the spacecraft. Nothing happened.

Our instruments suggested that an umbilical in the docking tunnel was not properly connected, halting the signal to operate the latches connecting the spacecraft. So I hurriedly floated back up into the docking tunnel and opened Endeavour’s hatch. If the spacecraft separated now, I was dead. I’d be shot out like a cork from a bottle as the oxygen in the crew cabin emptied into space.

I found that the umbilical cord was loose in its socket. So I unplugged it and rammed it back in. That should do it. Then I locked the hatch again and floated back into my couch.

I hit the switch again, and the two spacecraft gently slid apart. “You’re on your own,” Jim radioed to me.

I looked out of the window as we flew in formation. Falcon hung above me, its coppery sides glinting in the sunlight. The spidery spacecraft looked scarily fragile out there in deep space. “You’ve got four good-looking gear,” I told Dave, confirming that their landing legs were fully deployed. They continued to busily check out their spacecraft for their descent to the surface.

I prepared to burn Endeavour’s engine again, to raise me into a sixty-mile circular orbit and leave Dave and Jim behind. Without Falcon attached I was much lighter, and I really felt the acceleration when the engine lit. “What a kick in the tail!” I radioed to Dave. I zoomed behind and above Falcon, leaving them to land.

But it was more than a kick in the tail. I had my heart in my throat. We had removed the center couch so Dave and Jim could easily float into Falcon, but I had not put it back. This meant that there was nothing to stop my own seat on the left side from shifting on its supporting strut. When the engine lit, my couch swung toward the middle of Endeavour, away from my instrument panel. To my alarm, I realized I could no longer reach the controls.

I held on and hoped the computer was performing the burn correctly. If I needed to reach over to shut it off, I’d be in trouble. Within a few seconds as the acceleration peaked, I could swing the couch back and reach the instruments again. But it had been a scary moment.

Meanwhile, Ed Mitchell gave Dave and Jim the call—Falcon was go for powered descent to the surface. We’d taken five days to get to this moment, and their landing would only take another twelve and a half minutes. I’d come almost the whole way with them so far, but now they would make this brief journey without me.

It felt odd to see them grow smaller, until they were just a speck against the lunar background. I shot way ahead and quickly lost sight of them. But I listened to Ed, Dave, and Jim on the radio as Falcon’s descent engine fired and the lunar module dropped through the mountain range toward their Hadley Rille landing site. Minutes later, I heard Jim shout “Bam!” Falcon had thumped down firmly onto the lunar surface. I smiled in relief. They had made it.

“Okay, Houston, the Falcon is on the plain at Hadley,” Dave announced. I grinned. The Plain was the name of the parade field back at West Point, and I knew Dave had just named the landing site as a tribute to our academy.

President Nixon issued another message. “The president sends his congratulations to the entire ground team and the Apollo 15 crew on a successful landing, and sends his best wishes for the rest of the mission.” Boy, he got that message out to us fast.

“Houston, this is Endeavour. Thank you very much,” I responded. Thank you, Mr. President, for keeping it short this time.

And then I slipped around the back of the moon once again. This time, I would be completely alone. A quarter of a million miles away, planet Earth was home to all but three humans. Two of them, Dave and Jim, were now two thousand miles away on the other side of a big, dead ball of rock. And then there was me. With the moon in the way, I couldn’t talk to Dave or Jim, or Earth. I was the most isolated human in existence. I’d be on my own for three days.

It would have been great for all three of us to go down to the lunar surface. It was an exciting time for Dave and Jim, and it would have been fun for me, too. But I was happy where I was. In fact, it was my favorite part of the flight; I had that amazing spacecraft all to myself. We’d been cooped up together so closely, I enjoyed stretching out. Plus now I really got to fly. Like a test pilot checking out a new airplane, I would gain stick-and-rudder time in this enhanced version of the command and service module.

I didn’t feel lonely or isolated. I’d grown up able to take care of myself and had become a single-seat fighter pilot. I was much more comfortable flying by myself than with others. In fact, I most enjoyed the back side of the moon, where Houston couldn’t get hold of me on the radio. I was fascinated by what I was seeing and happy that Dave and Jim had landed safely—but glad to be rid of them for a while, too.

I was also going to be intensely busy. I was my own solo science mission now, with my own CapCom so my work was not confused with Dave and Jim’s. I’d already begun turning on some SIM bay instruments as soon as we were in lunar orbit. But now, with Falcon gone, I could really focus on my science tasks. I turned the spacecraft to aim the SIM bay at the lunar surface.

I had a meticulously choreographed three days ahead of me. The spacecraft would be in sunshine, in shadow, in and out of radio contact with Earth. I needed to use the sextant, the windows, and the SIM bay, each of which would need to be pointed in different directions for different tasks. But I couldn’t just turn the spacecraft any time I felt like it: my fuel was precious, and finite.

I extended the mass spectrometer on a large boom, trying to sniff out any hint of lunar atmosphere or escaping volcanic gas. Scientists particularly thought that areas of lunar sunrises and sunsets might concentrate stray gases. They would be extremely tenuous, and that is where we ran into trouble. The spectrometer mostly picked up particles that we brought from Earth. We’d sprayed clouds of urine along our flight path all the way to the moon, and these urine dumps continued in lunar orbit. My frozen pee is probably sprinkled all over the moon. Add rocket engine exhaust, and it is no wonder our mass spectrometer had trouble finding anything else.

In another effort to get away from the effects of the spacecraft, I also deployed the gamma-ray spectrometer on a large boom, to search for radiation emitted by the lunar surface. I activated other instruments to look for X-rays, plus alpha particles such as radon which volcanic cracks in the moon might emit. If I found them, it could reveal activity deep inside the moon. I even bounced the spacecraft’s radio signal off the moon and back to Earth, which gave us more details of the surface composition.

I often needed to control the spacecraft to keep it steadily curving around the moon, so that the panoramic camera could look straight down and take clear shots. If I were out of place, the camera would only capture blurry photographs as the landscape sped past below. I was flying over uncharted parts of the moon’s far side, so I wanted to get great shots.

The camera was a modified version of the device used by the U-2 spy plane and air force spy satellites. It was now obsolete, so NASA could use it. That camera was a phenomenal instrument—the lens and film moved together in one precise motion to image a huge swath of landscape. Using more than a mile of film, I took over fifteen hundred photos, capturing details only a few feet across. When we returned to Earth I found I’d even captured the shadow of Falcon on the moon and the disturbed lunar dust around the spacecraft where Dave and Jim had walked.

The military had placed one condition on our use of the camera. So there was no question of any international incidents, I was prohibited from pointing it at the Soviet Union. This was nonsense—from a quarter of a million miles away, the best image I would have captured was a fuzzy continent. But it had been a spy camera, so the diplomats had to be satisfied.

Another device, the mapping camera, rose out of the SIM bay on rails. I used it to snap precisely measured images of smaller patches of terrain. Using a star-seeking camera and a laser beam that bounced off the surface, I could match every photo with the exact angle and distance from the landscape. Shooting stripes of overlapping photos, I mapped the moon as explorers of old had mapped the earth. As my orbit shifted slightly westward with every revolution, I mapped a new area on each pass.

I kept on a precise, intensely busy schedule to open and close lenses and shutters, deploy and retract booms, and orient the spacecraft. But there was more. I would also take scientifically valuable photos myself out of the windows.

The moon looked enormous from such a low orbit. From Earth, I’d had no sense of its vertical features. Now as I zipped across the landscape I saw the outer rings of molten waves formed by meteor impacts frozen into gunmetal-gray mountains that reached fifteen thousand feet up toward me. I glimpsed tall central peaks of craters before I saw the surrounding low rims. As I constantly rounded a curved and angled surface, the tops of these hills would peek out over the horizon before I reached them, and once I passed over them the landscape would plunge thousands of feet in steep, shadowed crater walls. With no atmosphere to soften the view, every crater and boulder was sharp and crisp.

It was an alien world, but nevertheless it felt oddly familiar. Thanks to Farouk, every time I slid back into sunlight I recognized features right away. Craters, rilles, and overlapping, intermingling lava flows marched past that I knew from my training. I felt strangely comfortable—I knew this place.

The moon was an alien world, but somehow reassuringly familiar.

I wanted to see if I could spot Dave and Jim on the surface with my own eyes. I was not just curious: knowing their exact position would also help us dock three days later. Finding such a tiny object amid a plain of craters was not easy, but as I gazed through the sextant I caught a quick glint from Falcon’s shiny skin, then spotted their long shadow. “I’ve got the LM!” I announced to mission control. “He’s sitting right by a very small crater.” I rattled off their exact coordinates. “I hope the view is as fantastic down there as it is up here,” I radioed down to Dave.

“I’m telling you, it really is!” Dave assured me. “We’ll do the little things and you do the big things,” he added, as I studied the grand sweep of the landing region from above.

“I think we’re going to give lots of people lots of things to do for a while,” I told mission control. The three of us would be returning massive amounts of data to analyze.

Changes in color and shading fascinated me as I circled the moon. Looking toward the sun, the lunar surface appeared light brown. Away from the sun, it looked gray. I saw white splashes where fresher craters had blown out flour-like rays of powdery soil. Although I know this could not be possible, the bright rays often appeared to be suspended above the surface in a lacelike haze, not scattered across the mountains. The moon looked bleached and desert-like when the sun was directly overhead, as if clay had been mixed with sand. Then, as the sun lowered, evidence of long-ago violent events would appear in the lengthening shadows of old scars and wounds from impacts. I could see lava flows so thick that they must have crept across the surface in a slow, widening, sticky wave, filling old craters as they wound across the moon. It was like a jigsaw puzzle of features, each with its own secrets for me to piece together.

With no atmosphere, the line between day and night was strikingly distinct. Mountains cast long slashes of blackness across the landscape, and features stood out as if I had placed a flashlight against a rough stucco wall. I was fascinated by the starkness of the peaks. I loved to take photos in these shadowy regions—and not only because it helped the scientists. Back on Earth, they could use the shadows to measure the height of lunar features. But there was also a drama and beauty in these locations, and I concentrated much of my photography there.

Streaks of light would create alternating light and shadowy waves that once again stretched and seemed to billow and flutter as I curved into blackness. I felt like a sailor crossing a dark ocean. I knew photos could never capture what I observed. Neither can these words.

Once in darkness, I tried to take low-light-level photos of astronomical objects. With the moon cutting off light from the sun and Earth, the blackness was total. I would put my camera in the window and try for a ten-second exposure, using very fast film. It was tough to hold the spacecraft steady. I spent a lot of time working to keep Endeavour motionless, but in the end I decided it was impossible for more than a few seconds at a time. The spacecraft just wasn’t that delicate to maneuver. But I still took some great photos.

Endeavour had one window with no ultraviolet shielding or any other protection. Made of quartz, it was absolutely clear. I’d been warned never to look out of that window without sunglasses or be caught in a direct sunbeam. It could have ruined my eyes and burned my skin. But that window was invaluable for photos when Endeavour was in complete darkness.

I was fascinated by the dramatic long shadows where the sun was rising or setting on the moon.

As I would be the first person to fly over the Aristarchus crater, scientists had asked me to study it closely. Astronomers thought they had seen reddish glows there, suggesting the crater was volcanically active. It was such a pale, smooth, almost mirror-like crater that even in shadow it looked as if it was gleaming in sunlight. “Looking at Aristarchus, a little bit in awe,” I later told Karl.

I didn’t see any glowing, but other instruments picked up possible traces of seeping radioactive gases. Something interesting was going on there. I hoped my measurements would help scientists puzzle it out.

Most of my observations grew out of my extensive training with Farouk. But the perception of human eyes allowed me to note subtle differences from Farouk’s photos and theories almost right away. For example, as I flew over the immense Tsiolkovsky crater, I saw that the enormous central peak was a little higher and the outside rim better defined than we had imagined. In photos, the smooth, lava-filled crater floor looked darker than its surroundings, but with my own eyes I could see that it was different only in texture, not color.

The crater was so vast that when I crossed it I could see little else. The central peak rose like a Swiss alp, a towering pale slab of rock surrounded by boulders hundreds of feet wide. Gazing closely, I could see details of rock layers no camera had ever captured. It looked like something had smashed into the moon eons ago like a stone into a pond, leaving a rippled crater, a smooth basin of lava, and a central peak rebounding out of the lunar depths. It reminded me of a bright island rising from dark, smooth waters.

Gliding over Picard crater, I could see delicate layers of lava, like rings on a bathtub, all the way down the crater walls to the bottom. They alternated between thin light and dark bands. This beautiful effect was hard to capture on camera, but I could observe with my eyes and describe it in detail.

The moon was overwhelmingly majestic, yet stark and mostly devoid of color. Every orbit, however, I was treated to the sight of the distant Earth rising over the lunar horizon.

In my entire six days circling the moon, no matter what I was doing, I stopped to look at the Earth rise. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen or imagined.

Our planet was the only place with color—distant blues, browns, and greens—all focused in one tiny globe. Ethereal and small, it shone in the deep black of space, much brighter than the full moon appears from Earth. Photos of Earth from the moon have a flat quality, but looking at it with my own eyes Earth felt alive and captivating. It seemed to beckon like a warm refuge. More than a gorgeous sight, it was home.

Earth had seemed limitless when I had walked out on launch morning. Now it was a faraway sphere, so small that it was hard to believe everything I had done, everything I had seen, had happened down there. I now felt apart from Earthly affairs in a way I can’t describe. Perhaps you have to go to the moon to feel it. But I could see that Earth was truly finite. That distant ball could only support so many people and contain so many resources. Once it is gone, it’s gone. If humans didn’t unite and organize their lives, I pondered, we’d be in trouble. Our parochial interests, whether religious, economic, or ethnic, are all best served by trying to keep our tiny island in space livable. In fact, to live any other way suddenly felt like insanity to me.

I never grew tired of watching Earth rise above the moon.

It sounds cliché to write, and perhaps a little surprising coming from a military officer, but the experience was mind altering. And when I experienced the feeling for myself, I knew in my gut it was the truth. Ironically, I had journeyed all this way to explore the moon, and yet I felt I was discovering far more about our home planet, our Earth.

As the days passed I watched the Earth change phases just as the moon does from Earth. When I arrived, the Earth was about half full, but it gradually diminished to a delicate crescent. Only when I looked back at the Earth rising did I understand how far I had traveled. I was isolated, with only the radio to stay in touch. If I thought about it too much, it was almost a little scary—not the isolation, but the sheer distance. We had a long journey back.

Farouk and I had worked on something special for every time I saw the Earth rise. I’d noticed that, to the public, guys flying around the moon seemed kind of ho-hum, nothing exciting. How could I make it interesting? I talked about it with Farouk, and we decided the best way might be for me to say something interesting every time I came back into radio contact. We came up with a phrase that we thought might grab everyone’s attention: “Hello Earth, greetings from Endeavour.” Farouk wrote it out for me phonetically in nine foreign languages: Arabic, Chinese, French, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, German, Spanish, and even Russian. Along with English, I’d have ten different ways to say hello to the citizens of our planet and make the point that the Apollo program was for the whole Earth, not just America.

It worked. I tried to transmit a different variation on every solo orbit, and the world press paid a little more attention.

I had brief opportunities each day to talk to Dave and Jim down on the surface. It sounded like they were toiling through an impressive science exploration schedule of their own. I could even look down into the deep rille while passing over the Hadley plain and see enormous rocks in the canyon at the exact same moment Dave and Jim were parked at the rim in their rover.

“Pretty spectacular up beside that mountain, I bet,” I asked Dave one time.

“Oh man, it was super, just super,” he replied. “We’ve got some great pictures for you.”

“I hope I’ve got some good ones for you, too,” I happily replied. It was great to hear from them.

But I guess Jim was feeling grungy from all that moon dust. “Hey, Al, throw my soap down, will you? And my spoon,” he radioed. “I really need my soap.”

“Don’t mind if I use it, do you?” I responded, teasing him a little.

“Save me a little bit!” he pleaded in return.

Dave and I then bantered about saving the soap until we were all back in lunar orbit again. The conversation was lighthearted, but once again we were reassuring ourselves that everything would go to plan. Falcon would lift off and rendezvous with me in space. We were going to survive and see each other again.

I looked for Dave and Jim every time I flew across the landing site. It was never easy to find them, and usually I only caught a quick reflection from Falcon before I lost them. And yet I felt closer to them than the people on Earth I was talking to all the time. It was reassuring to chat briefly every day and confirm I was still there for their return trip. “Save us some food!” Jim quipped as I sailed overhead.

While they were roaming the surface, I was hanging in weightlessness, so I needed to exercise. I had a small cylindrical device called the Exergym. A nylon rope wove through a series of friction pulleys, so when I pulled on it the friction created tension that I could exercise against. It was a great idea, but the damn thing didn’t work.

We hadn’t even reached the moon when the nylon started to fray. It heated up when we used the device and stretched the rope into useless threads. This was puzzling, because crews before us had taken it and said it worked fine. I suspected they hadn’t used it much.

I still needed to exercise, so I improvised. With the center couch removed, I could hold on to the two struts in the middle of the spacecraft and push against them. I could do knee bends and run in place with my legs freewheeling in air. I felt my heart rate rise and could watch the attitude indicator and see the entire spacecraft rocking back and forward.

I’d been looking at the Littrow region of the moon a lot, because scientists were curious about the darker soils there. Were they evidence of volcanic activity? On one pass, I spotted something unusual. “There are a whole series of small, almost irregular-shaped cones,” I reported, “and they have a very distinct dark mantling … It looks like a whole field of small cinder cones down there.”

Unlike craters created by meteorites, cinder cones build up as debris is pushed out from a volcanic vent. I was seeing features that met the definitions I had studied.

“They’re somewhat irregular in shape,” I continued. “They’re not all round … and they have a very dark halo, which is mostly symmetric, but not always, around them individually.”

Mission planners had told me I wouldn’t be able to see features that small. But that wasn’t true. If I stared hard at a fixed point, it was tough to resolve. But if I swept my eyes around the general area, I could pick up a lot more detail.

As I described these funnels surrounded by dark rings, the geologists back on Earth grew excited. So much so that the last Apollo lunar mission, Apollo 17, was targeted for the Littrow region. That mission didn’t reach any cinder cones. Instead they found an impact crater that had punched through the surface, throwing up an unusually dark ring of subsurface volcanic ash and bright orange glass beads. Good enough.

My work days were busy, but I was floating around so I didn’t burn up much energy. The ground had assigned me seven or eight hours to sleep. I found I only needed three or four. It wasn’t because I was nervous; it was more because I was excited. I had a lot to do. I didn’t bother telling mission control I was awake. I used some of the time to finish up experiments and take photographs, but I also had hours of free time around the moon to just look out, marvel, and think.

I orbited alone in a detached, eerie silence, my spacecraft on a smooth trajectory. When I flew jets back on Earth, I was used to little bumps as I cruised through air and the roar of the engine. Here there was stillness and peace. It was more like riding in a hot-air balloon, drifting with no sensation of motion. I felt like an imaginary alien might when visiting Earth in a UFO, that this was not my planet. I was not from here, and perhaps not even supposed to be here. I was spying on an alien place.

The only noise came from pumps and fans running in the background, which I only noticed if something did not sound right. Just like driving a car, you only snap alert when you hear something unexpected. Since my life depended on this machine, I was hyperaware of unusual sounds.

Sometimes I played music, which only heightened my sense of eerie detachment. I had a cassette filled with songs by Simon and Garfunkel, The Moody Blues, Judy Collins, George Harrison, The Beatles, and some spoken-word extracts from James Cook’s journals. Occasionally, I’d wind the tape to Frank Sinatra’s “Fly Me to the Moon” and “Come Fly with Me” and hum along while I worked away on my experiments.

I would flip the cassette recorder and watch it lazily rotate while it played. It was odd to watch the laws of physics in action, as it would spin a couple of times, flip over, and continue to spin around a different axis. Space was weird.

I carried some songs by French singer Mireille Mathieu, who many called the successor to Édith Piaf. Her agent had contacted me to see if I would put some of her songs on my tape. I wasn’t sure that would be a good thing, but I asked what he had in mind. The next thing I knew, her agent had booked the two of them on a flight to Houston to talk to me. I told the center director about these uninvited guests, and he arranged a meeting in his office, where we met with her for a few minutes. Out of politeness, I took a couple of her songs on the flight. They were hauntingly good but very sad, so I only listened to them once. The moon was foreboding enough.

I knew I would never be coming back to the moon, so I took extra care to absorb every sensation, every experience. I also believed that it was not just for me personally. With only two lunar missions left after ours, I understood it would be years before humans would return. I needed to experience it for everyone.

I curved around the moon to where no sunlight or Earthshine could reach me. The moon was a deep, solid circle of blackness, and I could only tell where it began by where the stars cut off. In the dark and quiet, I felt like a bird of the night, silently gliding and falling around the moon, never touching.

I turned the cabin lights off. There was no end to the stars.

I could see tens, perhaps hundreds of times more stars than the clearest, darkest night on Earth. With no atmosphere to blur their light, I could see them all to the limits of my eyesight. There were so many, I could no longer find constellations. My vision was filled with a blaze of starlight.

Unlike some other astronauts who had time only for hurried glances, I had many hours, spread over many days, to look at this awe-inspiring view and think about what it meant. There was more to the universe than I had ever imagined.

It got me thinking about our whole concept of the universe. We can’t see much of it from Earth, at least with the naked eye. The more we learn, through telescopes, the more our view of the universe changes. We can only make sense of what we can see. Viewing so much more now with my own eyes, I could feel my own understanding changing rapidly. I sensed that there was so much more out there than our Earthly philosophies would lead us to believe.

With hundreds of billions of galaxies in the universe, I decided it was naïve to believe we were the only life. If only a minuscule percentage of the blazing stars I saw had Earth-like planets, life could be everywhere. If our solar system is a natural process, then the rest of the universe should follow similar patterns. In fact, what if life came to Earth from somewhere else in the universe? My mind raced with possibilities.

Was the space program more than an engineering program—could it be part of our genetic drive? I might be circling the moon at that moment not because of politics or the Cold War, but because we are hardwired to explore space. In a few billion years, our own sun will die. Perhaps life wanders from star to star over the millennia, refusing to stay and die? Apollo might be the first step of that hardwired survival instinct.

I looked at the blaze of stars and imagined life out there as continuous, like seeds flying through the air, some surviving, some not. I imagined life spreading between the stars, timeless, always there, adapting, propagating, spurred by survival.

These feelings were amplified by the sensation of weightlessness. It seemed so natural, so comfortable—as if I were coming home. As if I had been that way before or belonged in space. Perhaps the natural state of humans was traveling through space.

I didn’t come to any conclusions. I still don’t know what is out there. What I strongly sensed was that we as a species have not yet experienced enough of the universe. Whatever we believe now is probably not accurate. We have developed our ideas based only on what we can see, touch, and measure. Now I was having a glimpse into infinity and could only dimly sense, not understand, the journey ahead for humans.

It was humbling for a Michigan farm boy, whose biggest worry at one time had been thirty acres of hay. Alone on the far side of the moon, in darkness, as far from other humans as it was possible to be, I drank in the experience, over days and long sleepless nights. Decades later, I’m still pondering what I absorbed in those intense hours.

Karl Henize tried to keep me grounded with world events each day. “President Nixon yesterday declared his administration is determined to revitalize the American country …”

I interrupted him. “That’s your world right now. Our world’s up here right now, Karl.” Then I gave him some more detail about ancient rock avalanches over the enormous cliffs of Tsiolkovsky crater. I could catch up on politics when I got back.

Then Karl relayed more personal news—that he and Vance Brand had visited my apartment across the street from mission control. Now this was more interesting.

“Your folks are there,” Karl relayed, “and I guess, as you know, they’ve got a squawk box listening in on our loop with great interest. Except when you go behind the moon, then they watch the other show that’s taking place on the surface.”

That was good to hear. NASA had installed a device in my apartment so my parents could listen in to our conversations, including this one. I hoped they were enjoying themselves.

“They said to say hello,” Karl added. “Great, very good,” I replied. “Hello, folks!” A quarter of a million miles away, I imagined them smiling.

I looked in their direction. The crescent Earth was bright, the white clouds reflecting the sunlight perfectly. The moon below me was bright with Earthshine. It did not look the same as when it was bathed in direct sunlight. It seemed to glow with a ghostly radiance, like the pulse of a phosphorescent ocean.

I prepared for the sunrise. Faint streamers and tendrils of light arced above the lunar horizon, glowing gases from the corona around the sun. They were beautiful in their delicacy. Then, with an intensity that made me snap my head away, the white-hot glare of the sun rose above the moon.

I put the shades over the windows and settled in for my last sleep alone around the moon. It had already been the experience of a lifetime. We still had many days and adventures ahead until we’d find Earth once more.